Abstract

Background

Depression and anxiety among adolescents require further attention as they have profound harmful implications on several aspects of adolescents’ wellbeing and can be associated with life threatening risk behaviors such as suicide.

Objective

To examine the underlying risk factors for feeling so sad or hopeless and for feeling worried among adolescents in Saudi Arabia.

Methods

Data from Jeeluna® national survey was used. A cross-sectional, multi-stage, stratified, cluster random sampling technique was applied among a sample of students aged 10–19 years attending intermediate and secondary schools in Saudi Arabia. A self-administered questionnaire assessing several domains, including feeling so sad or hopeless and worried, was used to collect data. Logistic regression models were fitted to determine the different factors associated with mental health.

Results

A sample of 12,121 students was included in this study. Feeling so sad or hopeless and feeling worried were significantly more prevalent among females and older adolescents (p < 0.0001). The results showed that poor relationship with parents, negative body image, and chronic illness to be significantly associated with feeling so sad or hopeless and worried.

Conclusions

Symptoms suggestive of mental health problems among adolescents in Saudi Arabia are prevalent and deserve special attention. Adopting effective strategies, including regular screening and intervention programs are highly needed to better address, detect, and control early signs of these problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Adolescents aged 10–24 years comprise nearly 25% (1.8 billion) of the world’s 7.3 billion population. Out of the 1.8 billion, almost 9 out of 10 live in less developed countries [1]. In the Arab region, the majority of the population is below the age of 25 years [2]. Likewise, in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), 20% out of a 28 million population is between the ages 10–19 years [3].

Although it is believed that adolescence is a healthy time in an individual’s life, around 15% of the global burden of disease accounted for by disability adjusted life years (DALYs) is in the 10–24 years old age group [4]. During adolescence, several biological, cognitive, physiological, psychological, emotional and social changes emerge, and certain risky behaviors arise and are linked to adolescents’ health [4]. During this period, some mental health issues are also more likely to develop [5]. While mental disorders—in general—account for 45% of the burden of disease in 10–24 year olds [6], depression and anxiety are considered to be among its leading causes [7].

Mental health is an integral part of individuals’ wellbeing that is influenced not only by individual attributes or behaviors, but also by the overall social and economic circumstances and environmental factors [5]. A study by Collishaw and colleagues [8] showed a significant increase in the proportion of adolescents reporting frequent feelings of depression and anxiety where the figures had doubled between the 1980s and the 2000s.

Research on mental health problems including depression and anxiety among adolescents has found it to be associated with poor familial bonds [9], smoking [10, 11], substance use [12, 13], bullying and physical violence [14], suicide ideation and behavior [15,16,17], and other factors that have direct impact on adolescents’ health and wellbeing. Moreover, mental health problems during adolescence tend to persist into adulthood. Adults who suffer from depression during adolescence are at higher risk of developing major depressive disorders [18].

Although a major public health issue, adolescents’ mental health has not been granted much attention within the Arab region [19]. Gender disparities in mental health conditions are wider in the region and the burden of mental health disease is expected to continue to grow with the recent increases in regional crises over the years [19,20,21]. Results of the analysis of the Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS) that was conducted among 104,614 students from 19 low and middle income countries including Arab countries such as Jordan, United Arab Emirates, Lebanon and Morocco showed that around 35% of students reported having symptoms of depression [22]. In the KSA, individual studies have reported on the prevalence and risk factors of depression and/or anxiety [23,24,25,26] in subpopulations. The only nationally representative study addressing the prevalence of depression and anxiety among adolescents in the KSA is the Jeeluna® study, in which symptoms suggestive of depression and anxiety were found to be present among 14 and 6.7% of adolescents respectively [27]. With this current study, we aim to build on previous reports and identify the underlying correlates of symptoms of depression and anxiety among adolescents in the KSA, so as to better inform policy makers, plan suitable interventions, and find sustainable solutions.

Methods

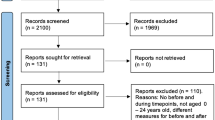

Data for this study was taken from the 2012 Jeeluna® national cross-sectional study. Jeeluna® is the first national study to assess the health status and health needs of adolescents in the KSA. It was conducted during the 2011–2012 academic year using student population proportionate, stratified, multistage, cluster sampling method. The sampling occurred at the district level and the sample size per district was proportionate to the student population within that district. Male and female students aged 10–19 years, and attending intermediate and secondary schools in public and private schools throughout the 13 regions of Saudi Arabia were invited to participate in the study, yielding a school response rate of 92.5% and a student response rate of 32%. Evening schools and schools serving special needs students were excluded. Data was weighted to ensure that it was nationally representative. The detailed methodology of Jeeluna® study was published earlier [27, 28].

Mental health domain is one of many other domains that were addressed in the Jeeluna® questionnaire. The questions were self-reported, and most of them were guided by the GSHS as well as the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS). For the current study, different variables including socio-demographics, chronic illness, relationship with parents, and others were extracted and analyzed. Symptoms of depression, referred hereafter as “feeling so sad or hopeless” was measured with the question “during the past 12 months, how often did you feel excessively sad or hopeless daily for 2 weeks or more to the extent that you stopped doing your usual activities?”, whereas symptoms of anxiety, referred hereafter as “feeling worried”, was measured with the question “during the past 12 months, how often have you felt so worried about something to the extent that you stopped doing your usual activities?”. These questions have been used in the past in adolescent health surveys [29] and are guided by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of Mental Disorders criteria for identifying underlying mental health disease. Answers were categorized as most of the time/always; or never/rarely/sometimes. Those who answered always or most of the time to those questions were considered as feeling so sad or hopeless and worried.

Data were weighted to account for the probability of selection of students within each school, hence obtaining unbiased results. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA 14.

p values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Descriptive statistics were obtained for the whole sample and results were reported in terms of percentages. Bivariate analysis was then performed to test for all possible associations between the dependent and independent variable. Adjusted and unadjusted odds ratios were then generated and presented.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC), as well as the Ministry of Education. Consent and assent forms were obtained from parents and students respectively, prior to participation in the study.

Results

Sample characteristics

Table 1 shows participants’ demographics. For the purpose of this paper, a secondary data analysis was conducted and a total number of 12,121 observations were considered. Fifty-three percent were males, and 53% were above 15 years of age. The mean age was 15.7 ± 3.4 years. The majority of participants were Saudis (86%). Most of the students (53%) were in intermediate schools and (46%) were in secondary schools. The distribution of the students differed across the four regions in proportion to the student population per region. As for the relationship with father and mother, the majority reported having a good relationship with 84 and 93% respectively. Overall, 14% reported feeling so sad or hopeless and 6% reported feeling worried during the past 12 months prior the survey. More females (62%) and older adolescents (>15 years of age) (59%) reported feeling so sad or hopeless. The same thing applies to feeling worried that was found to be more common among females and older adolescents (63% and 66% respectively) (all p values <0.001). Feeling so sad or hopeless and feeling worried were more common among Saudis vs non-Saudis. On the other hand, region showed no significant association with feeling so sad or hopeless and feeling worried.

Association of feeling so sad or hopeless and feeling worried with the different variables

At the bivariate level, our results revealed that age, gender, relationship with father and mother, chronic illness, body image, and exercise to be significantly associated with feeling so sad or hopeless and feeling worried (all p values <0.005). Nationality was not significantly associated with symptoms of feeling so sad or hopeless, yet it was significantly associated with feeling worried (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Feeling so sad or hopeless

At the multivariate level, the associations revealed that females and older adolescents are more likely to feel so sad or hopeless with (OR 1.94; 95% CI 1.69–2.23) and (OR 1.18; 95% CI 1.00–1.40) respectively. Moreover, adolescents who had “neither good nor bad” and “poor” relationship with father had higher odds of feeling so sad or hopeless as compared to those who had a good relationship with father (OR 1.77; 95% CI 1.44–2.16) and (OR 3.44; 95% CI 2.65–4.47) respectively. The same trend continues when it comes to the relationship with mother, the poorer the relationship was, the higher the odds of feeling so sad or hopeless as compared to those who had a good relationship with mother. Adolescents who believed they needed to lose weight were more likely to feel so sad or hopeless as compared to those who were happy with their bodies. Chronic illness was also positively associated with feeling so sad or hopeless. Adolescents who self- reported having chronic illness had more than twice the odds of reporting feeling so sad or hopeless (OR 2.31; 95% CI 1.86–2.87).

Feeling worried

In terms of statistical significance, results for the correlates of anxiety symptoms did not differ much from those of feeling so sad or hopeless. In particular, females (OR 1.88; 95% CI 1.56–2.28) and older adolescents (OR 1.56; 95% CI 1.25–1.94) were at higher odds of feeling worried as compared to males and younger adolescents. Adolescents who had a poor relationship with father or mother had respectively 4.3 and 2.64 times the risk of feeling worried as compared to those who had a good relationship with father or mother. As for nationality, our results showed that non-Saudis had higher odds of feeling worried as compared to Saudis (OR 1.3; 95% CI 1.04–1.63). Feeling of worrisome was also significantly associated with chronic illness, with adolescents with chronic illness having twice the risk of feeling worried as compared to those who were generally healthy. On the other hand, body image, exercise and region showed no statistical significance at the multivariate level.

Discussion

The prevalence rate of depression (14%) and anxiety (6%) symptoms previously reported by the Jeeluna® [27] fall within the wide range reported by different studies on depression and anxiety in the region [25, 30, 31] which made us realize the importance highlighting this issue and further investigating its underlying risk factors.

Our findings of feeling so sad or hopeless and feeling worried being more prevalent among females and older adolescents, was found to be consistent with others’ findings [32,33,34]. This was also supported by results reported by the analysis of the GSHS data that was conducted across 19 low and middle income countries including Morocco, Lebanon, Jordan and United Arab Emirates [22]. The higher prevalence rates among females can be attributed to different factors including genetics, biological, psychological or behavioral factors [35].

Poor family relationships or conflictual interactions within a family environment, as well as the lack of affection and support are correlated with depressive symptoms [36], as it is with other risk behaviors, such as bullying and violence [14]. This was also shown in our study, where poor relationship with mother or father was found to be significant risk factors feeling so sad or hopeless and feeling worried among adolescents in the KSA. The poorer the relationship with parents was, the higher the odds of feeling so sad or hopeless and feeling worried. Those results are aligned with the literature on this issue [26, 36, 37]. A study conducted among female adolescents in Riyadh has shown depression to be more prevalent among those who had bad relationship with their family members [26]. Other studies have also documented the importance of family roles in protecting adolescents from risky behaviors. For example, a national study about suicide ideation among adolescents in Lebanon showed that parental understanding was a protective factor against suicide ideation [15]. A regional study about adolescent and family connectedness among eight Arab societies, including Saudi Arabia, found that Arab adolescents, despite the social and cultural disparities among these societies, scored high on the connectedness to their families with females showing more connectedness than males [38]. These findings highlight the opportunity to capitalize on family relationships and connectedness and work towards focusing on building positive, strong and effective parenting and communication skills through launching awareness and educational campaigns or programs that target parents. Such programs may aim at enhancing parenting matters through equipping parents with the necessary knowledge about adolescents’ physical, emotional and mental development. After all, knowledge is a key variable in this equation; if parents are made aware of the protective impact of positive relationship with children, and their significant role in shaping their children’s well-being, they might become more engaged and more willing to take a step forward and make a difference.

Similar to other reports from different parts of the world [39,40,41], body image has been found to be a significant predictor of feeling so sad or hopeless and feeling worried among adolescents; those who thought they need to gain weight or lose weight were more likely to be feel so sad or hopeless. Similarly, a longitudinal study among 2139 US adolescent boys conducted between 1996 and 2009 found that distorted body image to be a risk factor for elevated depressive symptoms and tend to persist to adulthood [39]. This result is not surprising in a time where people have become deeply immersed in social media and so influenced by the ‘perfect-body’ image that may eventually affect their satisfaction with their bodies.

As for adolescents with chronic illnesses, our findings showed it to be significantly associated with mental health; similarly, a huge body of literature have documented the serious effects that chronic illness has on adolescents’ mental health [42, 43]. In their meta-analysis, Pinquart and colleagues [44] had shown that children and adolescents with chronic physical illnesses had higher levels of depressive symptoms as compared to their healthy peers. This was also documented in a study among a subpopulation of high school students in KSA, in which they found chronic illness to be a significant risk factor for depression [24].

Given the cross-sectional nature of this study, the causal inference between the dependent and independent variables cannot be established; however, our study reveals several underlying risk factors for feeling so sad or hopeless and feeling worried among adolescents in the KSA and sets the ground for more in-depth longitudinal studies that can better reflect on this situation. On the other hand, the strength of this study resides in the generalizability of the results being the first study to address mental health and associated risk factors among a nationally representative sample of adolescents in Saudi Arabia, which in turn sets a baseline for research on adolescents’ mental health in the country. Adolescents’ mental health is an important issue that is, unfortunately, being widely underestimated. A huge body of research unveils the deleterious effects that depression during adolescence has on their wellbeing, not only as adolescents but as future adults too. This can be avoided through early detection of symptoms when present and effective school and community-based interventions that are tailored to the Saudi cultural context where, as in many other Middles Eastern countries, mental health problems are still stigmatized [45]. Accordingly, mental health interventions in the Middle East should take into account the fundamental role of families, adolescent-family connectedness and stigma associated with mental health [38, 46].

Ministry of Health and School Health Programs should work hand in hand in planning public awareness campaigns and training programs that target adolescents, parents and teachers. Parents should be well educated about the importance of positive communications with adolescents and this should not be difficult for an Arab country like Saudi Arabia, where family ties are highly cherished and families are considered to be the first line of support and protection.

Annual screening for depression, as recommended by the United States Preventive Services Task Force [47] should be implemented in schools. Effective professional counseling services should be implemented at all schools to help support students better cope with their problems, be it social, emotional or behavioral. Attention to capacity building in adolescent health, including adolescent mental health, is much needed [48] and will provide healthcare providers with the necessary knowledge, awareness, and skills for addressing adolescents’ health needs. Though some attention to this has begun with the first Adolescent Health and Medicine Capacity Building Workshop in the Region in 2016 (AlBuhairan, unpublished), much more is needed. Lastly, the civil society should also be held accountable for planning prevention programs that promote positive mental health and creating a supporting environment so as to overcome shame and stigma linked to mental health.

Conclusions

Mental health issues are a major public health concern that have serious implications on adolescents’ wellbeing. This study reveals the underlying risk factors of symptoms of depression and anxiety among adolescents in Saudi Arabia and highlights the importance of taking the necessary actions and planning suitable interventions that can lessen its harmful impact if not preventing it. Further in-depth research studies that assess adolescents’ mental health using diagnostic tools for depression and anxiety are needed. Also, parents–adolescents research in Saudi Arabia is missing and requires closer investigation.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- KSA:

-

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- PV:

-

physical violence

- GSHS:

-

Global School-based Student Health Survey

- YRBSS:

-

Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System

References

United Nations Population Funds. The power of 1.8 billion adolescents, youth and the transformation of the future. United Nations Population Funds; 2014. http://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/EN-SWOP14-Report_FINAL-web.pdf. Accessed 23 Feb 2017.

UNPY. Regional overview: youth in the Arab region. New York: United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia and the United Nations Programme on Youth (UNPY).

US Census Bureau. International Programs. International Data Base. 2016. Accessed 23 Feb 2017.

Sawyer SM, Afifi RA, Bearinger LH, Blakemore S-J, Dick B, Ezeh AC, et al. Adolescence: a foundation for future health. Lancet. 2012;379:1630–40.

World Health Organization. Risks to mental health: an overview of vulnerabilities and risk factors. Geneva: WHO; 2012.

Gore FM, Bloem PJ, Patton GC, Ferguson J, Joseph V, Coffey C, et al. Global burden of disease in young people aged 10–24 years: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011;377:2093–102.

Patel V. Why adolescent depression is a global health priority and what we should do about it. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:511.

Collishaw S, Maughan B, Natarajan L, Pickles A. Trends in adolescent emotional problems in England: a comparison of two national cohorts twenty years apart. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51:885–94.

Séguin M, Manion I, Cloutier P, Mcevoy L, et al. Adolescent depression, family psychopathology and parent/child relations: a case control study. Can Child Adolesc Psychiatr Rev. 2003;12:2–9.

Fergusson DM, Goodwin RD, Horwood LJ. Major depression and cigarette smoking: results of a 21-year longitudinal study. Psychol Med. 2003;33:1357–67.

Johnson JG, Cohen P, Pine DS, Klein DF, Kasen S, Brook JS. Association between cigarette smoking and anxiety disorders during adolescence and early adulthood. JAMA. 2000;284:2348–51.

Skogen JC, Sivertsen B, Lundervold AJ, Stormark KM, Jakobsen R, Hysing M. Alcohol and drug use among adolescents : and the co-occurrence of mental health problems. Ung@hordaland, a population-based study. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005357.

Wu P, Goodwin RD, Fuller C, Liu X, Comer JS, Cohen P, et al. The relationship between anxiety disorders and substance use among adolescents in the community: specificity and gender differences. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39:177–88.

AlBuhairan F, Abbas OA, El Sayed D, Badri M, Alshahri S, de Vries N. The relationship of bullying and physical violence to mental health and academic performance: a cross-sectional study among adolescents in Saudi Arabia. Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2017;4:61–5.

Mahfoud ZR, Afifi RA, Haddad PH, Dejong J. Prevalence and determinants of suicide ideation among Lebanese adolescents: results of the GSHS Lebanon 2005. J Adolesc. 2011;34:379–84.

Fotti SA, Katz LY, Afifi TO, Cox BJ. The associations between peer and parental relationships and suicidal behaviours in early adolescents. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51:698–703.

Thompson EA, Mazza JJ, Herting JR, Randell BP, Eggert LL. The mediating roles of anxiety, depression, and hopelessness on adolescent suicidal behaviors. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2005;35:14–34.

Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y. The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:56–64.

Obermeyer CM. Adolescents in Arab countries: health statistics and social context. DIFI Fam Res Proc. 2015;1.

AlBuhairan FS. Adolescent and young adult health in the Arab region: where we are and what we must do. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57:249–51. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.06.010.

World Health Organization. Health for the world’s adolescents: a second chance in the second decade. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

Fleming LC, Jacobsen KH. Bullying among middle-school students in low and middle income countries. Health Promot Int. 2010;25:73–84. doi:10.1093/heapro/dap046.

Al Gelban K. Prevalence of psychological symptoms in Saudi secondary school girls in Abha, Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29:275.

Abdel-Fattah MM, Asal ARA. Prevalence, symptomatology, and risk factors for depression among high school students in Saudi Arabia. Neurosciences. 2007;12:8–16.

Mahfouz AA, Al-Gelban KS, Al Amri H, Khan MY, Abdelmoneim I, Daffalla AA, et al. Adolescents’ mental health in Abha city, southwestern Saudi Arabia. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2009;39:169–77.

Raheel H. Depression and associated factors among adolescent females in Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, a cross-sectional study. Int J Prev Med. 2015;6:90.

AlBuhairan FS, Tamim H, Al Dubayee M, AlDhukair S, Al Shehri S, Tamimi W, et al. Time for an adolescent health surveillance system in Saudi Arabia: findings from “Jeeluna”. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57:263–9. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.06.009.

AlBuhairan FS. Jeeluna study: national assessment of the health needs of adolescents in Saudi Arabia. Riyadh: King Adbullah International Medical Research Center; 2016.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. YRBSS|Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System|Data|Adolescent and School Health|CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/index.htm. Accessed 13 June 2017.

Ismayilova L, Hmoud O, Alkhasawneh E, Shaw S, El-Bassel N. Depressive symptoms among Jordanian youth: results of a national survey. Community Ment Health J. 2013;49:133–40.

World Health Organization. Maternal, child and adolescent mental health : challenges and strategic directions 2010–2015. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

Hankin BL, Mermelstein R, Roesch L. Sex differences in adolescent depression: stress exposure and reactivity models. Child Dev. 2007;78:279–95.

Bennett DS, Ambrosini PJ, Kudes D, Metz C, Rabinovich H. Gender differences in adolescent depression: do symptoms differ for boys and girls? J Affect Disord. 2005;89:35–44.

Lewinsohn PM, Gotlib IH, Lewinsohn M, Seeley JR, Allen NB. Gender differences in anxiety disorders and anxiety symptoms in adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107:109–17.

Piccinelli M, Wilkinson G. Gender differences in depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:486–92.

Sheeber L, Hops H, Davis B. Family processes in adolescent depression. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2001;4:19–35.

Sheeber LB, Davis B, Leve C, Hops H, Tildesley E. NIH public access. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007;116:144–54.

Dwairy M, Achoui M, Abouserie R, Farah A. Adolescent-family connectedness among Arabs: a second cross-regional research study. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2006;37:248–61. doi:10.1177/0022022106286923.

Blashill AJ, Wilhelm S. Body image distortions, weight, and depression in adolescent boys: longitudinal trajectories into adulthood. Psychol Men Masc. 2014;15:445–51.

Ozmen D, Ozmen E, Ergin D, Cetinkaya AC, Sen N, Dundar PE, et al. The association of self-esteem, depression and body satisfaction with obesity among Turkish adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:80.

Marcotte D, Fortin L, Potvin P, Papillon M. Gender differences in depressive symptoms during adolescence: role of gender-typed characteristics, self-esteem, body image, stressful life events, and pubertal status. J Emot Behav Disord. 2002;10:29–42.

Greydanus D, Patel D, Pratt H. Suicide risk in adolescents with chronic illness: implications for primary care and specialty pediatric practice: a review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52:1083–7.

Haarasilta L, Marttunen M, Kaprio J, Aro H. Major depressive episode and physical health in adolescents and young adults: results from a population-based interview survey. Eur J Public Health. 2005;15:489–93.

Pinquart M, Shen Y. Depressive symptoms in children and adolescents with chronic physical illness: an updated meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36:375–84.

Sewilam AM, Watson AMM, Kassem AM, Clifton S, McDonald MC, Lipski R, et al. Roadmap to reduce the stigma of mental illness in the Middle East. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2015;61:111–20. doi:10.1177/0020764014537234.

Almakhamreh S, Hundt GL. An examination of models of social work intervention for use with displaced Iraqi households in Jordan. Eur J Soc Work. 2012;15:377–91.

US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Final recommendation statement: depression in children and adolescents: screening. 2016. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/depression-in-children-and-adolescents-screening1. Accessed 14 Mar 2017.

AlBuhairan FS, Olsson TM. Advancing adolescent health and health services in Saudi Arabia: exploring health-care providers’ training, interest, and perceptions of the health-care needs of young people. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2014;5:281–7. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S66272.

Authors’ contributions

OA participated in analytic plan, data analysis and interpretation, and drafting of article. FA conceived of the study, acquired the funding, participated in its design, analytic plan, data management, and drafting of article. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank King Abdullah International Medical Research Center for supporting and funding the Jeeluna® project.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Review Committee at the King Abdullah International Medical Research Center. A written parental consent and student assent were sought prior to student participation.

Funding

This study was supported and funded by King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (Protocol Number RC08-092).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Abou Abbas, O., AlBuhairan, F. Predictors of adolescents’ mental health problems in Saudi Arabia: findings from the Jeeluna® national study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 11, 52 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-017-0188-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-017-0188-x