Abstract

There is increasing knowledge that the COVID-19 pandemic has had an impact on mental health of children and young people. However, the global evidence of mental health changes before compared to during the COVID-19 pandemic focusing on children and young people has not been systematically reviewed. This systematic review examined longitudinal and repeated cross-sectional studies comparing before and during COVID-19 pandemic data to determine whether the mental health of children and young people had changed before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Web of Science, PubMed, Embase and PsycINFO databases were searched to identify peer-reviewed studies that had been published in English and focused on children and young people between 0 and 24 years of age. This identified 21 studies from 11 countries, covering more than 96,000 subjects from 3 to 24 years of age. Pre-pandemic and pandemic data were compared. Most studies reported longitudinal deterioration in the mental health of adolescents and young people, with increased depression, anxiety and psychological distress after the pandemic started. Other findings included deteriorated negative affect, mental well-being and increased loneliness. Comparing data for pandemic and pre-pandemic periods showed that the COVID-19 pandemic may negatively impact the mental health of children and young people. There is an urgent need for high-quality research to address the impact, risks and protective factors of the pandemic on their mental health, as this will provide a good foundation for dealing with future health emergencies and other crises.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There is growing concern about the negative effects that the COVID-19 pandemic is having on the mental health of children and young people, particularly those who are already vulnerable. A number of factors have contributed to mental health issues in these age groups, including emotional, physiological and behavioral stress. These have been due to factors such as social isolation, due to school closures, parental stress about the virus and employment, increases in undetected child abuse, increased cyber bullying, due to more online activities, and the trauma of losing family members [1, 2]. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic may have increased loneliness, depression and anxiety and decreased life satisfaction [3]. Increased suicidality and suicide attempts by adolescents during the pandemic has also been reported [4]. Lockdowns and physical distancing may have had a different impact on some children and young people, depending on their age, gender, ethnicity, family circumstances, socioeconomic situation and any pre-existing mental health problems [5,6,7,8].

To our knowledge, five systematic reviews have been published on the mental health of children and young people during the COVID-19 pandemic, four in 2021 and one in 2020. Meherali et al. and Nearchou et al. only included cross-sectional studies carried out at one time-point [9, 10]. Racine et al. conducted a meta-analysis, which reported that the global prevalence of anxiety and depression among children and adolescent were 25.2% and 20.5% with 95% confidence intervals (CI) of 21.2–29.7 and 17.2–24.4, respectively, for the period from February to July 2020 [11]. Samji et al. attempted a broader systematic review, by examining 116 papers with any empirical study design [12], while Panchal et al. systematic review included 61 papers [13]. However, more than 70% included studies in both reviews were cross-sectional studies and they also included specific clinical subgroups. This makes it difficult to discern the mental health changes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic toward the general children and young people population samples. Samji et al. have stated that the priority for COVID-19 research should be representative samples and/or longitudinal follow-up studies that have the potential to demonstrate changes in mental health symptoms before and after the pandemic [12].

Different indicators for mental health problems should be measured repeatedly before and during the COVID-19 pandemic to assess changes in mental health trends during the pandemic. These should use directly comparable measures, sampling designs and convergent information from multiple sources, such as parents, teachers and children [14, 15].

The aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the existing global literature, so that we could compare the mental health of children and young people aged 0–24, before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, and identify any changes.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

The review study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [16]. The protocol of the review was prospectively registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO number: CRD42021238999). The Web of Science, PubMed, Embase and PsycINFO electronic databases were used to identify peer-reviewed papers published in English from 1 January 2020 to 22 March 2021. The search syntax for each database is listed in Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix. We also used the backward snowballing technique to search for other relevant papers [17], by looking at the reference lists of the selected papers.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies with children and young people aged 0–24 years were included. Children were defined as 0–9 years old and young people as 10–24 years of age. We refer to the definition of adolescents (10–19 years old) and young people (10–24 years old) by the World Health Organization [18, 19] that include adolescents as defined by Sawyer et al. (10–24 years old) [20]. Population, community or school-based studies were included. We did not include studies that focused on individuals aged 25 or older or studies that did not report the specific age ranges of the subjects.

The review included any observational studies that used surveys or interviews to determine the mental health symptoms of subjects before and during the pandemic. These included longitudinal, repeated cross-sectional, cohort, panel, time series and time trend studies. We excluded single cross-sectional studies, studies that using modeling to predict the impact of the pandemic on mental health or studies that used different measures to compare outcomes before and during the pandemic. The periods before and during the pandemic were the pandemic periods defined by the authors of the included studies and at least one corresponding pre-pandemic period. It is worth noting that we have previously reported findings on the registered mental health service use, self-harm and suicides based on administrative data [21] so these types of studies were also excluded in this review.

The following mental health outcomes were included; externalizing and internalizing problems, attention-deficit/hyperactivity problems, negative and positive effects, depression, anxiety, psychological distress, health-related quality of life, peer problems and loneliness. Only studies that reported at least one validated measure of these mental health outcomes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic were included. The studies were only included if the same measures and/or methods were used for each outcome before and during the pandemic.

Study selection and retrieval process

The screening and study selection processes were independently conducted by two reviewers (LK and WMAWMY), first based on the titles and abstracts, after removing the duplicates. If there was insufficient information in the title and abstracts, the full texts were retrieved and reviewed to determine the study's eligibility. Any disagreements were discussed with a senior researcher (DG) and professor (AS). The two reviewers independently conducted full-text assessments based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Both reviewers cross-checked the included papers and any disagreements were discussed, and resolved, with the senior researcher and professor.

Quality assessment

The quality of the studies was assessed using 14 items from the National Institutes for Health (NIH) Study Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies [22]. These covered the study power, the strength of the causality in the association between exposure and outcomes and the risks of potential selection bias, information bias, measurement bias or confounding bias. Studies were then categorized as good, fair or poor quality and reported using the total score for each study (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Data extraction and synthesis

We then extracted the relevant data and placed them into an Excel spreadsheet, version 16.43 (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA). These included the author, country, study design, sample, informants, age, sampling methods and response rates. We also extracted the pre-pandemic and pandemic timepoints, mental health outcomes and measures, the descriptive data before and during the pandemic and the inferential analysis results. The key findings were extracted and the changes to mental health were divided according to each outcome into three categories that showed whether the subject’s mental health had deteriorated, improved or showed no difference. Where available, we also extracted information on the influence on gender, age and existing poor mental health problems and whether these were significant factors in the association to mental health before and during the pandemic.

Results

Study selection and retrieval processes

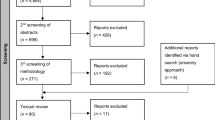

The electronic and manual searches identified 2675 citations. A total of 575 duplicates were removed and the other 2100 records were screened for eligibility. Following the title and abstract screening, 1969 records were excluded and the full texts of 131 papers were evaluated. We excluded 110 full texts because they did not compare before and during COVID-19 pandemic timepoints, they did not provide specific data for individuals aged 0–24, used different measure before and during pandemic timepoints, focus on clinical samples or were based on administrative data. At the end of this process, 21 studies were included in the qualitative synthesis. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram for the screening and study selection processes.

Description of the included studies

The systematic review comprised 21 mental health studies published in 2020 and 2021, covering a total study population of more than 96,000 subjects aged from 3 to 24 years of age in 11 countries. The summary of the studies and the mental health changes are presented in Table 1. The data ranged from January 2009, before the pandemic, to October 2020, during the pandemic. Twelve studies collected data during the initial phase of the pandemic (up to April 2020) [8, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33], seven studies collected data between April and June 2020 [7, 34,35,36,37,38,39], and one study each collected data from June to July 2020 [40] and October 2020 [41] respectively. Five studies were conducted in the UK [24, 27, 28, 35, 40] and in China [23, 30,31,32,33], two studies in the USA [8, 25], Italy [26, 36] and Australia [29, 39] and one study in India [34], Canada [37], Spain [38], Germany [7] and Iceland [41]. The NIH rating showed that 12 were rated as good-quality studies and nine studies were rated as fair quality (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Study designs and sampling

A longitudinal study design was used in 17 studies [8, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32, 34,35,36,37, 39, 41] and a repeated cross-sectional study design was used in four studies, with different samples at two time points [7, 33, 38, 40]. A nationally representative, population-based dataset or probability sampling was used in seven studies, with sample sizes ranging from 407 to 59,701 subjects [7, 8, 23, 24, 27, 28, 41]. Probability sampling was used in six studies [7, 8, 23, 24, 27, 28] and one was a nationwide study of all adolescents aged 13–18 years [41], which allowed the findings to be generalized at the population level. Non-representative and non-probability sampling was used in 14 studies, with sample sizes that ranged from 101 to 3886 subjects [25, 26, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40].

Three quarters (16/21) of the studies covered subjects 10 years old or more, while only five studies included children below 10 years old: 3–11 years [26], 4–6 years [37], 6–17 years [23], 7–11 years [35] and 7–17 years [7]. The informants were children and/or young people in 16 studies [8, 24, 25, 27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34, 36, 38,39,40,41]. Two studies used information from parents [26, 37], two used parents and children or young people [7, 23] and one study used a mixture of parents, teachers and children report [35]. All the studies used same informants in the pre-pandemic and pandemic phases.

Mental health outcomes

All 21 studies measured mental health outcomes during both pre-pandemic and pandemic time points using the same measures. Depression was assessed in 10 studies [7, 8, 23, 25, 26, 30, 33, 35, 39, 41], anxiety was assessed in 9 studies [7, 8, 25, 30, 32,33,34,35, 39] and psychological distress in 4 studies [24, 27,28,29]. Mental well-being [40, 41], loneliness [8, 24], stress [30, 38], positive and negative affect [31, 36] and hyperactivity/impulsivity [7, 37] were assessed in 2 studies respectively. One study assessed both depression and anxiety as one outcome [31]. Quality of life, emotional symptoms, conduct problems and peer problems were assessed in one study [7].

Changes in mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

Most of the studies reported that mental health deteriorated during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings are summarized in Fig. 2. Increased depressive symptoms were reported by eight studies [8, 25, 26, 30, 33, 35, 39, 41], while one study each reported improve depressive symptoms [23] or no significant difference [7] after the pandemic started. Increased anxiety were reported by eight studies [7, 8, 25, 30, 32,33,34, 39] while one study found no significant difference [35]. Increased psychological distress was found by all four studies [24, 27,28,29]. Increased in stress or emotional stress were found in two studies [30, 38], while one study reported no difference in physiological and behavioral stress [38]. Decreased mental well-being was reported by two studies [40, 41]. Two studies reported increased in loneliness [8, 24]. Increases in the negative affect was found in two studies [31, 36], while decreases in positive affects was found in one study [36] and no significant decrease in positive affect in the other study [31].

Mental health change findings for those aged 10–24 years consistently pointed to the deterioration of mental health. We used the World Health Organization definition of children and young people which include adolescents although we noted the arbitrary upper age limit used in some previous studies. The five studies that included children below 10 years old showed varying pattern and mental health outcomes. Out of the 21 included studies, the only study reporting improvement in mental health (depression) symptoms during the pandemic, was a study in China on school children aged 6–17 years [23]. Another study from the UK on those aged 7–12 years found depression symptoms worsened but reported no significant changes for anxiety symptoms and emotional problems [35]. Increased inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity were found in a study in Canada on young children aged 4–6 years [37]. A repeated cross-sectional study in Germany on children and adolescents aged 7–17 years reported significantly lower health-related quality of life, higher conduct problems, hyperactivity and peer problems during the pandemic, although no significant change for emotional symptoms was reported [7]. A longitudinal study in Italy reported significant deterioration in attentional problems, emotional regulation, hyperactivity, and willingness to study among primary school children aged 6–11.1 years. While similar changes were not shown in any of the outcomes among preschool children aged 3.2–6.2 years [26].

There were few studies assessed the significant influence of of age, gender differences and existing poor mental health when it came to mental health differences before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Five studies found that mental health symptoms had worsened more in girls than boys [27, 32, 33, 39, 41]. In contrast, one study based on parental reports on adolescents aged 7–17 reported higher increases in mental health problems among boys than girls, in particular in externalizing problems including conduct problems, hyperactivity and peer problems [7]. Two of the largest studies in this review that focused on subjects aged 13–18 [41] and 11–20 [33] years found that mental health problems increased more in older than younger participants during the pandemic. Four studies that looked at subjects aged 16–24 years [27, 40] and 18–24 years [24, 28] compared to subjects older than 24 years old reported higher self-reported psychological distress [24, 27, 28] and higher decreased in mental well-being [40] in these age groups.

Three studies found greater effects in those who already had poor mental health before the COVID-19 pandemic [8, 27, 28]. Young women aged 16–24 who already had poor mental health in the pre-pandemic period, recorded increasing severe problem from 17.7% to 35.2% during the pandemic [27]. Another study showed the steepest increase in the proportion of clinically significant psychological distress in 2020, compared to 2014–2019, among female aged 16–24, the age group with already the highest proportions before the pandemic [28]. One study also showed depressive symptoms before the pandemic were a strong indicator of depressive symptoms among subjects aged 14–17 years during the pandemic [8]. Notably, one study of subjects aged 7–17 years reported that decreases in mental health were most significant in families with low socioeconomic status, migration background and limited living space [7].

Discussion

To our knowledge, this was the first systematic review to focus on collecting empirical evidence on studies focusing on children and young people aged 0–24 to assess changes in mental health symptoms before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The studies included more than 96,000 subjects up to 24 years of age before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our systematic review of 21 studies from 11 countries had four main findings. First, most of the 21 studies reported a longitudinal deterioration in symptoms for different mental health outcomes especially for adolescents and young people. Second, the overall picture that emerged was that the mental health changes for younger children aged 0–9 years and the influence of gender, age and existing mental issues was limited in our included studies. Third, there was a very limited number of large-scale, repeated cross-sectional designs with clear sampling frames. Fourth, there were also no cross-cultural studies identified that compared how different policies, namely lockdowns, school closures and other social restrictions, may have affected the mental health of the children and young people.

We found that the 21 studies included 23 measures of anxiety, depression or psychological distress and that 20/23 (87%) showed increased levels. There was also some evidence of deteriorated negative affect, mental well-being and increased loneliness during the pandemic. Our review extended the findings from four previous reviews that were largely based on cross-sectional studies [10,11,12,13] that showed mental health of children and adolescents may have worsened during the current pandemic. Our findings of deteriorating mental health have global significance, because of the potential long-lasting consequences for the well-being of individuals, families and societies. Numerous birth cohort studies have showed that poor mental health in childhood predicted future mortality and morbidity [42, 43]. In addition, childhood mental health problems have been associated with lower socioeconomic status and less stable social relationships in adulthood [44]. Our previous systematic review showed decreased mental health service use before and during the pandemic in subjects aged 0–24 years during the early phase of COVID-19 pandemic [21]. These two contradictory findings, of increased mental health problems but decreased service use during the early pandemic, indicated unmet needs.

The papers covered by the current review were all based on observational studies and any explanations for why mental health problems increased are largely lacking. Majority of the included studies collected during pandemic data at a very early stage of pandemic, when the more stringent restrictions were largely being implemented globally. A recent longitudinal study on adult population in 15 countries showed that more stringent COVID-19 policies throughout the first 15 month of the pandemic is linked to poorer mental health [45]. Thus, it’s important to note that the present findings reflect the impact during the early phase of the pandemic on the mental health of children and young people. Other studies showed increased online or social media use [46, 47] and problems related to remote learning [48, 49]. These factors need to be explored, together with potential explanations like social isolation, family dysfunction, restricted leisure time activities, worries about being infected or about friends and family being infected and grief at losing loved ones.

Our systematic review showed that few studies have assessed the influence of demographic factors in association with the changes in mental health before and during the pandemic. Given that limited studies have assessed these factors and the variability of outcome in these studies, these results were inconclusive, but mainly in line with previous reviews [9, 11, 12]. Girls and older adolescents were associated with higher deteroriation in mental health symptoms during the pandemic. Mental health symptoms rose more strongly among female than their male peers and this may suggest that they might have been more vulnerable to the psychological effects of the pandemic. Depression and anxiety are increasing during puberty especially among girls [50, 51], which may be one possible explanation for this gender differences. Of note, a previous review showed that the COVID-19 lockdown may have worsened eating disorders symptoms, which are much more common in female [52]. Also, subjects were significantly more affected if they had a pre-existing mental problem [8, 27, 28], low socioeconomic status, migration background and limited living space [7]. More robust research are needed to replicate these findings.

This review has several implications for the methods that should be used by future studies. First, we only found a limited number of studies with large-scale, repeated cross-sectional designs and clear sampling frames. Collishaw’s criteria on time trend studies emphasize the need for comparable measures, clear sampling frames, convergent data by multiple informants and multiple data time points [14]. These kind of study designs are needed for future research, especially as the pandemic remains a global situation. It is possible that the psychological well-being of children and young people will be even more severely affected after longer exposure to the stressors associated with the pandemic. It has been argued that ongoing social isolation, family financial difficulties, missed milestones and school disruption, due to COVID 19 pandemic, will have cumulative adverse effects on the mental health of young people [11]. Second, there were no cross-cultural studies and these are needed to examine how different policies related to school closures and other restrictions have affected child mental health. Research that focuses on the impact of different policies will help societies to be more prepared to address new crises in a more effective and research-based way, such as future pandemics, threats of war and environmental catastrophes. Finally, rigorous studies that identify risk and resilience factors in children and young people during global crises are still lacking. These are urgently needed, so that effective health promotion and prevention strategies can be developed that maintain good mental health in challenging situations.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of the study included the fact that the 21 papers we reviewed covered more than 96,000 children and young people aged from 3 to 24 years in 11 countries. These papers provided data on a range of mental health issues and indicated changes in mental health by comparing pre-pandemic and pandemic data. The review also had a number of limitations. We chose not to conduct a statistical meta-analysis, because of the heterogeneity of the study designs and mental health outcomes used by the studies we reviewed. In addition, only peer-reviewed papers published in English were included and we may have missed studies in other languages. Although 21 studies were included, only seven studies had a representative population-based dataset and we were unable to assess mental health on a larger scale. There was also lack of studies on children below 10 years old, limiting the interpretation that can be drawn for this age group. Finally, all the studies that we reviewed focused on changes during the early phase of the pandemic. Future research is needed to see whether subsequent waves had a different impact on the mental health of children and young people.

Conclusions

This systematic review of 21 peer-reviewed papers showed that the COVID-19 pandemic may have decreased the mental health of adolescents and young people in 11 countries. Future studies are needed to determine the long-term impact of the pandemic on their well-being especially on younger children. It is likely that the world will face similar threats in the future and that these could have an impact on mental health, including new pandemics, wars or environmental catastrophes. Therefore, research on how the COVID-19 pandemic, and different isolation, lockdowns and school closures policies, have affected families, children and young people in different countries, is vital if we are to build future sustainable societies.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability (software application or custom code)

Not applicable.

References

Babvey P, Capela F, Cappa C, Lipizzi C, Petrowski N, Ramirez-Marquez J (2021) Using social media data for assessing children’s exposure to violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse Negl 116:104747

Fore HH (2021) Violence against children in the time of COVID-19: What we have learned, what remains unknown and the opportunities that lie ahead. Child Abuse Negl 116:104776

Daly M, Sutin AR, Robinson E (2021) Depression reported by US adults in 2017–2018 and March and April 2020. J Affect Disord 278:131–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.065

Mayne SL, Hannan C, Davis M, Young JF, Kelly MK, Powell M, Dalembert G, McPeak KE, Jenssen BP, Fiks AG (2021) COVID-19 and adolescent depression and suicide risk screening outcomes. Pediatrics 148(3):e2021051507. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-051507

Ha T, Van Roekel E, Iida M, Kornienko O, Engels RC, Kuntsche E (2019) Depressive symptoms amplify emotional reactivity to daily perceptions of peer rejection in adolescence. J Youth Adolesc 48:2152–2164

Pasca L, Zanaboni MP, Grumi S, Totaro M, Ballante E, Varesio C, De Giorgis V (2021) Impact of COVID-19 pandemic in pediatric patients with epilepsy with neuropsychiatric comorbidities: a telemedicine evaluation. Epilepsy Behav 115:107519

Ravens-Sieberer U, Kaman A, Erhart M, Devine J, Schlack R, Otto C (2021) Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents in Germany. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 31:879–889. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01726-5

Rogers AA, Ha T, Ockey S (2021) Adolescents’ perceived socio-emotional impact of COVID-19 and implications for mental health: results from a US-based mixed-methods study. J Adolesc Health 68:43–52

Meherali S, Punjani N, Louie-Poon S, Abdul Rahim K, Das JK, Salam RA, Lassi ZS (2021) Mental health of children and adolescents amidst COVID-19 and past pandemics: a rapid systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:3432

Nearchou F, Flinn C, Niland R, Subramaniam SS, Hennessy E (2020) Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on mental health outcomes in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:8479

Racine N, McArthur BA, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Zhu J, Madigan S (2021) Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 175:1142–1150

Samji H, Wu J, Ladak A, Vossen C, Stewart E, Dove N, Long D, Snell G (2021) Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and youth–a systematic review. Child Adolesc Mental Health 27(2):173–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12501

Panchal U, Salazar de Pablo G, Franco M, Moreno C, Parellada M, Arango C, Fusar-Poli P (2021) The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: systematic review. Europ Child Adolesc Psych. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01856-w

Collishaw S (2015) Annual research review: secular trends in child and adolescent mental health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 56:370–393

Smith DJ, and Rutter, M (1995) Psychosocial disorders in young people: time trends and their causes. Academia Europaea/John Wiley

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, McKenzie JE (2021) PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n160

Wohlin C (2014) Guidelines for snowballing in systematic literature studies and a replication in software engineering. In: Proceedings of the 18th international conference on evaluation and assessment in software engineering 1–10

McDonagh JE, Ambresin A-E, Boisen KA, Fonseca H, Jakobsson Kruse P, Meynard A, Stronski S, Michaud P-A, Takeuchi YL (2018) The age of adolescence adolescence… and young adulthood. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2:e6

World Health Organization (2003) Adolescent friendly health services: an agenda for change. In: World Health Organization, WHO/FCH/CAH/02.14. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/67923

Sawyer SM, Azzopardi PS, Wickremarathne D, Patton GC (2018) The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2:223–228

Wan Mohd Yunus WMA, Kauhanen L, Sourander A, Brown JS, Peltonen K, Mishina K, Lempinen L, Bastola K, Gilbert S, Gyllenberg D (2022) Registered psychiatric service use, self-harm and suicides of children and young people aged 0–24 before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 16:1–13

National Institutes for Health (2021) Study quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

Xiang M, Yamamoto S, Mizoue T (2020) Depressive symptoms in students during school closure due to COVID-19 in Shanghai. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 74:664–666

Niedzwiedz CL, Green MJ, Benzeval M, Campbell D, Craig P, Demou E, Leyland A, Pearce A, Thomson R, Whitley E, Katikireddi SV (2021) Mental health and health behaviours before and during the initial phase of the COVID-19 lockdown: longitudinal analyses of the UK Household Longitudinal Study. J Epidemiol Community Health 75:224–231

Huckins JF, da Silva AW, Wang W, Hedlund E, Rogers C, Nepal SK, Wu J, Obuchi M, Murphy EI, Meyer ML, Wagner DD, Holtzheimer PE, Campbell AT (2020) Mental health and behavior of college students during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal smartphone and ecological momentary assessment study. J Med Int Res 22(6):e20185. https://doi.org/10.2196/20185

Gimenez-Dasi M, Quintanilla L, Lucas-Molina B, Sarmento-Henrique R (2020) Six weeks of confinement: psychological effects on a sample of children in early childhood and primary education. Front Psychol 11:590463. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.590463

Banks J, Xu XW (2020) The mental health effects of the first two months of lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK*. Fisc Stud 41:685–708

Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, Hatch S, Hotopf M, John A, Kontopantelis E, Webb R, Wessely S, McManus S, Abel KM (2020) Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry 7:883–892

Munasinghe S, Sperandei S, Freebairn L, Conroy E, Jani H, Marjanovic S, Page A (2020) The impact of physical distancing policies during the COVID-19 pandemic on health and well-being among Australian adolescents. J Adolesc Health 67:653–661

Li WW, Yu HZ, Miller DJ, Yang F, Rouen C (2020) Novelty seeking and mental health in chinese university students before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: a longitudinal study. Front Psychol 11:600739. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.600739

Li HY, Cao H, Leung DYP, Mak YW (2020) The psychological impacts of a covid-19 outbreak on college students in China: a longitudinal study. int j environ res public health 17(11):3933. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17113933

Wang CY, Zhao H, Zhang HR (2020) Chinese college students have higher anxiety in new semester of online learning during COVID-19: a machine learning approach. Front Psychol 11:587413. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.587413

Chen X, Qi H, Liu R, Feng Y, Li W, Xiang M, Cheung T, Jackson T, Wang G, Xiang YT (2021) Depression, anxiety and associated factors among Chinese adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak: a comparison of two cross-sectional studies. Translat Psychiatry 11:148. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01271-4

Manjareeka M, Pathak M (2020) COVID-19 lockdown anxieties: is student a vulnerable group? J Indian Assoc Child Adolesc Ment Health 17:72–80

Bignardi G, Dalmaijer ES, Anwyl-Irvine AL, Smith TA, Siugzdaite R, Uh S, Astle DE (2020) Longitudinal increases in childhood depression symptoms during the COVID-19 lockdown. Arch Dis Childhood 106(8):791–797. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2020-320372

Alivernini F, Manganelli S, Girelli L, Cozzolino M, Lucidi F, Cavicchiolo E (2021) Physical distancing behavior: the role of emotions, personality, motivations, and moral decision-making. J Pediatr Psychol 46:15–26

Wendel M, Ritchie T, Rogers MA, Ogg JA, Santuzzi AM, Shelleby EC, Menter K (2020) The association between child ADHD symptoms and changes in parental involvement in kindergarten children’s learning during COVID-19. Sch Psychol Rev 49:466–479

Liebana-Presa C, Martinez-Fernandez MC, Benitez-Andrades JA, Fernandez-Martinez E, Marques-Sanchez P, Garcia-Rodriguez I (2020) Stress, emotional intelligence and the intention to use cannabis in spanish adolescents: influence of COVID-19 confinement. Front Psychol 11:582578. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.582578

Magson NR, Freeman JYA, Rapee RM, Richardson CE, Oar EL, Fardouly J (2021) Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Youth Adolesc 50:44–57

Gray NS, O'Connor C, Knowles J, Pink J, Simkiss NJ, Williams SD, Snowden RJ (2020) The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental well-being and psychological distress: impact upon a single country. Front Psychiatry 11:594115. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.594115

Thorisdottir IE, Asgeirsdottir BB, Kristjansson AL, Valdimarsdottir HB, Jonsdottir Tolgyes EM, Sigfusson J, Allegrante JP, Sigfusdottir ID, Halldorsdottir T (2021) Depressive symptoms, mental wellbeing, and substance use among adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iceland: a longitudinal, population-based study. Lancet Psychiatry 8(8):663–672. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00156-5

Maughan B, Stafford M, Shah I, Kuh D (2014) Adolescent conduct problems and premature mortality: follow-up to age 65 years in a national birth cohort. Psychol Med 44:1077–1086

Thapar A, Collishaw S, Pine DS, Thapar AK (2012) Depression in adolescence. Lancet 379:1056–1067

Goodman A, Joyce R, Smith JP (2011) The long shadow cast by childhood physical and mental problems on adult life. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108:6032–6037

Aknin LB, Andretti B, Goldszmidt R, Helliwell JF, Petherick A, De Neve J-E, Dunn EW, Fancourt D, Goldberg E, Jones SP, Karadag O, Karam E, Layard R, Saxena S, Thornton E, Whillans A, Zaki J (2022) Policy stringency and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal analysis of data from 15 countries. Lancet Publ Health 7:e417–e426

Duan L, Shao X, Wang Y, Huang Y, Miao J, Yang X, Zhu G (2020) An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in china during the outbreak of COVID-19. J Affect Disord 275:112–118

Ellis WE, Dumas TM, Forbes LM (2020) Physically isolated but socially connected: psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Can J Behav Sci 52:177

Almeida M, Challa M, Ribeiro M, Harrison AM, Castro MC (2022) Editorial perspective: the mental health impact of school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 63(5):608–612. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13535

Hawrilenko M, Kroshus E, Tandon P, Christakis D (2021) The association between school closures and child mental health during COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open 4:e2124092

Knight JA, Kehm RD, Schwartz L, Frost CJ, Chung WK, Colonna S, Keegan THM, Goldberg M, Houghton LC, Hanna D, Glendon G, Daly MB, Buys SS, Andrulis IL, John EM, Bradbury AR, Terry MB (2020) Prepubertal internalizing symptoms and timing of puberty onset in girls. Am J Epidemiol 190:431–438

Salk RH, Hyde JS, Abramson LY (2017) Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychol Bull 143:783–822

Sideli L, Lo Coco G, Bonfanti RC, Borsarini B, Fortunato L, Sechi C, Micali N (2021) Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on eating disorders and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Eat Disord Rev 29:826–841

Funding

Open Access funding provided by University of Turku (UTU) including Turku University Central Hospital. This study was funded by the Academy of Finland via a COVID-19 grant (number 335690, PI Gyllenberg) and the INVEST-flagship (number 320162, PI Sourander), and by the Juho Vainio Foundation. The funders had no involvement in any aspect of the study or manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS and DG obtained the funding and initiated the idea for the review article; LK and WMAWMY performed the literature search and screening; LK, WMAWMY, LL, KP and AS drafted the article; LK, WMAWMY, LL, KP, DG, KM, SG, KB, JB and AS critically revised the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval (include appropriate approvals or waivers)

The manuscript does not contain clinical studies or patient data.

Informed consent (include appropriate statements, for example regarding “consent to participate” or “consent to publish”)

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kauhanen, L., Wan Mohd Yunus, W., Lempinen, L. et al. A systematic review of the mental health changes of children and young people before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 32, 995–1013 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-02060-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-02060-0