Abstract

Background

Research around humanitarian crises, aid delivery, and the impact of these crises on health and well-being has expanded dramatically. Ethical issues around these topics have recently received more attention. We conducted a systematic literature review to synthesize the lessons learned regarding the ethics of research in humanitarian crises.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines to identify articles regarding the ethics of research in humanitarian contexts between January 1, 1997 and September 1, 2019. We analyzed the articles to extract key themes and develop an agenda for future research.

Results

We identified 52 articles that matched our inclusion criteria. We categorized the article data into five categories of analysis: 32 were expert statements, 18 were case studies, 11 contained original research, eight were literature reviews and three were book chapters. All included articles were published in English. Using a step-wise qualitative analysis, we identified 10 major themes that encompassed these concepts and points. These major themes were: ethics review process (21 articles, [40.38%]); community engagement (15 articles [28.85%]); the dual imperative, or necessity that research be both academically sound and policy driven, clinical trials in the humanitarian setting (13 articles for each, [25.0%)]; informed consent (10 articles [19.23%]); cultural considerations (6 articles, [11.54%]); risks to researchers (5 articles, [9.62%]); child participation (4 articles [7.69%]); and finally mental health, and data ownership (2 articles for each [3.85%]).

Conclusions

Interest in the ethics of studying humanitarian crises has been dramatically increasing in recent years. While key concepts within all research settings such as beneficence, justice and respect for persons are crucially relevant, there are considerations unique to the humanitarian context. The particular vulnerabilities of conflict-affected populations, the contextual challenges of working in humanitarian settings, and the need for ensuring strong community engagement at all levels make this area of research particularly challenging. Humanitarian crises are prevalent throughout the globe, and studying them with the utmost ethical forethought is critical to maintaining sound research principles and ethical standards.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Defined as both natural and man-made disasters, along with both acute and chronic conflicts, humanitarian crises threaten the lives and livelihoods of over 131 million people in the world today [1]. With more than 68.5 million people currently displaced, 25.4 million of whom are refugees outside their country of origin, the global community is witnessing urgent humanitarian issues that are crossing borders and impacting even those states and communities once thought immune [2, 3]. Humanitarian aid is the impartial, independent and neutral delivery of services to populations in immediate danger [4]. Since the end of World War II, the humanitarian aid sector (in the form of health services, water and sanitation services, nutritional goods and security) has grown tremendously [5].

With expansion in humanitarian aid delivery and the deepening awareness that humanitarian crises can destroy health systems and have long-term impacts on public health, ensuring that the services provided are effective and acceptable is crucial. Following several highly publicized failures of the humanitarian community, veteran humanitarians from across the spectrum of governmental and non-governmental organizations have attempted to improve humanitarian response [6]. Initiatives such as the Sphere Project and others aimed to create minimum standards and evidence-based protocols for the delivery of five core components of humanitarian response—water supply and sanitation, nutrition, food aid, shelter and site planning and health services [7]. Over the past several decades, a key component of the assessment process has been conducting formal monitoring, evaluation and research on humanitarian aid delivery. Studies ranging from randomized control trials to population surveys and qualitative assessments evaluating the full spectrum of humanitarian aid delivery have burgeoned [8].

Parallel to the increase in professionalization of humanitarian aid, the public health community has been grappling with how to ensure that research on vulnerable populations is conducted ethically and with a focus on the rights and best interests of the community. Spurred by a backlash to unchecked human experimentation carried out through the twentieth century during World War II and the decades afterwards, there is more recognition of the critical importance of considering research ethics, particularly when studying vulnerable populations [9].

Few populations are as vulnerable to the potential adverse ethical challenges of research as those experiencing a humanitarian crisis [10]. Faced with weak government protections, disrupted health systems, insecure living conditions, and unreliable food and unsafe water, disaster-affected populations can be particularly at risk of inadequate consent processes and coercion. Furthermore, humanitarian emergencies require timely evaluation and management, making traditional ethics review—typically a protracted process—impractical [11,12,13]. These unique challenges, along with underdeveloped oversight and regulatory bodies of host countries and international mechanisms, make ethics considerations a crucial but difficult task in humanitarian research [14, 15].

Despite increasing interest and an expanding literature base, there has been limited formal synthesis of the existing published data around the ethical issues of research in the humanitarian setting. We conducted a systematic review to (1) identify ethical issues surrounding research in humanitarian settings, (2) assess how these issues are managed in these unique circumstances and (3) develop an agenda for major issues that will require further discourse.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [16]. The PRISMA checklist has been provided as Supplementary Table 1. Articles relevant to research ethics in the humanitarian setting were identified and analyzed. We chose to limit the search to articles published after January 1, 1997, when the initiation of the Sphere project marked a paradigm shift in how humanitarian aid was envisioned and carried out. This allows for review of nearly 25 years of literature, therefore spanning a wide swath of potential ethical research. We used the Sphere project dates because it included explicit language highlighting the need for evidence-based practices, which would require significant augmentation in research efforts to provide such an evidence base [7]. Our search included articles published as late as September 1, 2019, when this study was first undertaken.

Search strategy

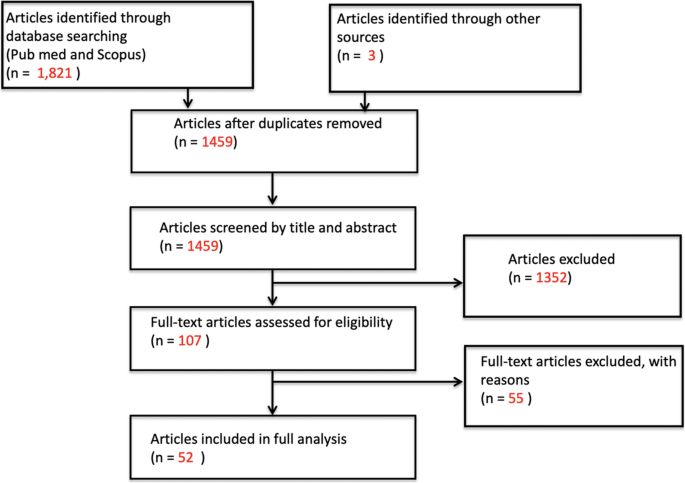

We searched PubMed and Scopus for articles with significant discussion of the ethical issues of humanitarian research ethics. After a qualitative assessment of relevant keywords, we identified all pertinent articles based on the following terminology categories (articles could be in any language): (1) humanitarian settings (terms such as humanitarian, global health, disaster, emergency and/or conflict), (2) ethics (terms such as ethic(s), bioethics, human rights and/or rights) and (3) research type (terms such as research, program evaluation, monitoring and evaluation and/or investigation). The full search strategy and MeSH terms can be found in theAppendix. The initial search results of 1459 articles underwent a title and abstract review followed by a full text review by two different authors (WB and RH) (Fig. 1). A priori inclusion criteria included the 22-year timeframe mentioned above and selected for articles with robust discussion of ethical issues in the context of conducting research in humanitarian settings. Any article deemed by both reviewers to contain only a superficial mention of ethical issues and to not substantively (1) discuss ethics or (2) focus on research (3) in the context of humanitarian settings was excluded from the final analysis. Ethics was defined broadly as engagement with specific research ethics, as well as human rights issues, and other non-formal discussions of right versus wrong and other moral concepts. Research was defined as discussions including any types of data collection including quantitative and qualitative, as well as data collection for monitoring and evaluation for other programmatic and academic purposes. Humanitarian settings included diverse contexts including conflict and post-conflict states, post-natural disaster settings and refugee camps that requires specific interventions to prevent large scale suffering of the populations. Two authors (WB and RH) reviewed the final list of articles meeting the inclusion criteria.

Analytical methods

We used a modified meta-ethnographic approach to inductively identify key concepts and synthesize the major themes [17]. We chose the meta-ethnographic approach as it has been shown useful in other systematic reviews of qualitative health literature in that it utilizes an inductive approach that can account for differences in methodology and focus, and has the potential to provide a higher level of analysis and generate new research questions [18,19,20]. We conducted three steps of analysis: (1) Identifying original concepts and ideas from each paper that related to cross-cutting themes; (2) synthesizing these ideas into cross-cutting themes; and (3) identifying major themes. These steps are outlined in Table 2. Original concepts were topics discussed in each paper, which the authors felt had some relevance to this paper’s focus on humanitarian research ethics. Cross-cutting themes were key concepts that were identified in at least two different articles. We assessed how the cross-cutting themes may fall into broader overarching ideas and coded these into related non-mutually exclusive groups we termed major themes. The synthesis process of extracting these major themes was one of reciprocal translation and constant comparison of concepts across studies. The process elucidated tensions and areas for future research within each major theme, as shown in Table 2. Any disagreements on the analysis were resolved with discussion and consensus.

This research, based on previously published literature, did not meet criteria for Institutional Review Board approval.

Results

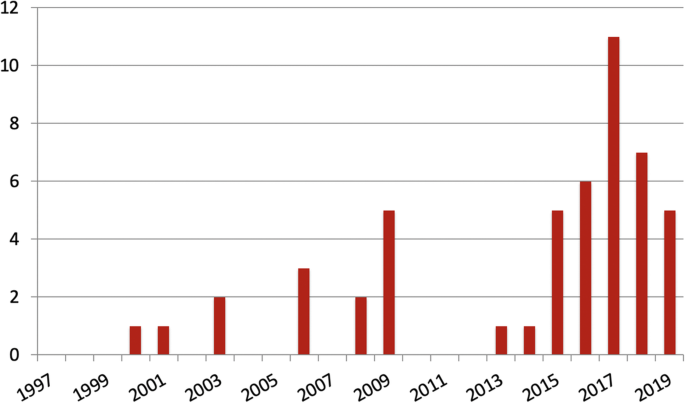

Of the 1459 unique articles resulting from our search terms, 52 matched our inclusion criteria (Table 1: List of Included Articles). The articles took the shape of five non-mutually exclusive categories of analysis: 32 were expert statements, 18 were case studies, 11 contained original research, eight were literature reviews and three were book chapters. All included articles were published in English. Thirty-four of the 52 (65.38%) articles were published in 2015 or later, ten between 2007 and 2014, and eight were published in the 1997–2006 decade (Fig. 2). Of the 52 articles included for final analysis, 23 were published by international teams (meaning that they were comprised of members from at least two different countries), 12 were from the United States, six from the United Kingdom, three from Canada, two each form Ireland, Trinidad and Tobago, and Switzerland, and one each from Australia and India.

Thematic analysis

The step-wise analysis is presented in Table 2. First order analysis of the articles meeting our final inclusion criteria revealed ideas and issues within the context of ethics related research in humanitarian settings. In the second phase of the analysis, qualitative review of the reports identified cross-cutting themes between the papers, and 10 major themes that encompassed these concepts and points. These major themes in descending order of prevalence were ethics review process (21 articles, [40.38%]); community engagement (15 articles [28.85%]); the dual imperative, or necessity that research be both academically sound and policy driven and clinical trials in the humanitarian setting (13 articles for each, [25.0%]); informed consent (10 articles [19.23%]); cultural considerations (6 articles, [11.54%]); risks to researchers (5 articles, [9.62%]); child participation (4 articles [7.69%]), and finally mental health, and data ownership (2 articles for each [3.85%]).

Ethical review

Discussion of the ethical review process was the most commonly identified theme, with 21 articles having a substantive focus on this [11, 21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. Independent ethics review prior to the start of a study is a core component of research ethics. Tansey et al. conducted a survey of ethics review board members with experience in reviewing research ethics in disaster settings. Their results suggest a general feeling that research in this setting is not only of particularly high social value, making it a desirable pursuit, but also necessitates a higher level of justification due to the inherent vulnerability of the research subjects [33]. There is also general agreement that the innate fluidity and urgency of humanitarian situations make swift and efficient ethics review of paramount importance [11, 25, 29]. Hunt et al. report, “where research is launched in response to a sudden-onset disaster such as an earthquake or hurricane, researchers may need to initiate their protocols quickly in order to answer research questions pertinent to the acute phase of the disaster response” [11]. However, as mentioned above, the particular vulnerability of the subjects being studied leads many research ethics committees to automatically identify humanitarian research as requiring “the highest level of stringency”. On the other hand, framing research as “needs assessments” and/or “monitoring and evaluation,” which is often done in evaluating aid needs and programs, may act to sideline rigorous ethical review and jeopardize the well-being of the recipient population [11]. This contradiction of values makes ethical review of humanitarian research particularly challenging.

Authors suggested strategies to mitigate the inherent challenges of ethics review in this setting [25]. For example, Hunt et al. suggest pre-approved research protocol templates which can be quickly customized for use in individual emergencies [11]. Eckenwiler et al. propose what they refer to as ‘real-time responsiveness,’ which is an iterative strategy of constant dialogue between ethics reviewers and researchers while studies are being conducted [24]. Given the potential for misstep in an expedited initial ethics review, Chiumento et al. describe the utility of a post-research ethical audit. The authors explain how this could help to evaluate “procedural ethics against in-practice realities”, which could help inform future studies [21]. Ethical analysis after data collection may also offer the added benefit of offering lessons on the review and practice process to the reviewers and researchers.

Our results highlighted the particular case of how the humanitarian aid agency Médecins Sans Frontières’ (MSF), who conducts substantial research in humanitarian settings, has devised an independent Ethics Review Board (ERB). The ERB utilizes several of the strategies mentioned above such as pre-approved protocols, engaging in ongoing dialogue between researchers and the ERB and conducting post-research evaluations [29, 31]. Saxena et al. reported on a joint panel conducted by the WHO and the African Coalition for Epidemic Research, Response and Training. The authors outline the group’s recommendations for “rapid and sound ethics review”, which includes “preparing national ethics committees for outbreak response; pre-crisis review of potential protocols; multi-country review; coordination between national ethics committees and other key stakeholders; data and benefit sharing; and export of samples to third countries” [32]. Indeed, as Mezinska et al. point out in their systematic review of ethical guidelines, most of the analyzed documents included in their report did “not attempt to give researchers and other stakeholders a comprehensive overview of how to proceed ethically in all types of research and in all types of disasters”, which the authors see as problematic given that “disaster research is unavoidably context and time sensitive, making generalized guidance less applicable” [35].

Community engagement

Substantive involvement of the community being studied was identified as an imperative for researchers and a major theme of discussion in 15 articles [21, 22, 30, 32, 33, 41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50]. It was generally agreed that active participation is necessary in order to fulfill the ethical requisite that research be of use to the community being studied (also known as beneficence) [22, 48, 50]. As Chiumento et al. identified in their systematic review of mental health literature, the right to participate in research can be viewed as a basic right in and of itself, insofar as it relates to other rights such as self-determination and autonomy [22]. One important strategy described was involving local community health and government officials in an effort to maximize community support [43]. More practically speaking, this effort can help limit potential for a community’s misunderstanding of research, which can jeopardize a project’s legitimacy and undermine its acceptance [46]. Early involvement of community actors, potentially via consultation during study protocol design or community meetings, was suggested [21, 42].

The discussions within the articles suggest that community involvement also involves strengthening local institutions, effectively improving their ability to conduct their own research [21, 22]. Despite being recognized as an important component of ethical research, it was generally agreed that there is a critical shortage of local capacity to carry out studies, particularly in post-conflict zones where formal institutions are often eroded [45, 47]. In their study on the research capacity of Somaliland, Boyce et al. identified potential harms of a “dominance of authors from [High-Income Countries]” [45]. They explain that, for example, the unrelatability between researcher and subject could lead to a reduced relevance of the research question.

Despite the agreement for “a set of practices that help researchers establish and maintain relationships with the stakeholders to a research program”, Tansey et al. discuss some of the inherent challenges in community participation. Particularly when conducting disaster research, the practicality of including locals can be difficult when “you don’t know when the disaster is going to hit. .. so it would be hard to set up community approvals and engagement beforehand” [33]. Furthermore, lack of adequately trained researchers and poor local infrastructure are perennial problems [45]. While ethically desirable, partnering with the local community may, in many circumstances, often prove practically prohibitive.

While including local authorities in research may seem prudent on face value, as discussed in the section on cultural considerations, these articles make clear the potential for ethical ambiguity when dealing with such actors [47, 49]. For example, in a civil war context, researchers may hope to adhere to humanitarian principles of impartiality to ensure access to participants and safety for researchers [49]. Furthermore, as Funk et al. describe in their evaluation of the response to the Syrian conflict, remaining impartial can be impossible. One respondent explained, “You have to understand that even though we declare ourselves as a non-biased health organization with no political standing, the mere fact that we are not ‘pro-government’ makes us [perceived as] ‘the enemy’ and ‘anti-government’” [49].

The dual imperative

Thirteen articles discuss what humanitarian researchers refer to as the ‘dual imperative,’ which is the inherent tension between ensuring that research is both academically sound and practically relevant [28, 41, 53, 55, 57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64, 71]. Despite the inherent challenges in humanitarian research, the general consensus is that it is justifiable insofar as it is needs-driven and not at the expense of humanitarian action [60]. However, as researchers attempt to construct sophisticated research and attract funding, there is a move toward a greater level of academic sophistication [59]. On the individual level, a member of a humanitarian response team may feel responsibilities as both service provider and researcher [58, 61]. Wood, in her description of experiences researching conflict zones in El Salvador, describes an inevitable self-inquiry of why this research is worth pursing at the expense of a purely humanitarian medical relief mission. She concludes that her role as a researcher was justified in that a sound understanding of conflict is necessary for its abolishment. Wood does, however, concede that this conclusion may be predicated on the nature of the “relatively benign and coherent conditions” of her work. Specifically, she “did not have to make a decision whether or not to intervene to attempt to prevent or mitigate an attack on civilians.” She “did not have to decide how to leave an area under attack at short notice, retreating with one force or seeking shelter from another.” She was “never faced with direct threats [insisting] that [she] turn over material [she] had gathered” and did not have “to judge how far to press respondents about violence they had suffered or observed because of the focus of [her] research.” The implication was that had she been faced with one of these more charged situations, her resolve in the justification of research would be challenged. In fact, she ends her discussion by stating that “conditions in many civil wars simply preclude ethical field research” [62].

Another related point of contention identified in our search is a disagreement that arose between a researcher and aid agency. Due to an overtaxed and under resourced system, the Democratic Republic of Congo had engaged in rationing of AIDS medications. Rennie, a global health researcher, had intended to study the community attitudes toward this practice [55]. Feeling rationing medications to be unethical, the aid agency Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), specifically MSF-Belgium, wrote a letter informing Rennie that they would not support his investigation [55, 63]. They expressed concern that the research might be a form of acquiescence to the practice of drug rationing, which they see as antithetical to the humanitarian mission [63]. This tension between assessing an existing program and unintentionally bringing legitimacy to it is one of many practical conflicts in humanitarian research that requires further consideration.

Clinical trials in the humanitarian setting

Given that clinical trials are considered imperative for investigating medical interventions, many researchers advocate for these types of studies in the humanitarian setting. Thirteen articles explore the ethics of conducting clinical trials in the humanitarian setting [27, 29, 30, 36, 38, 46, 51,52,53,54,55,56, 63]. Lanini et al. make the point that the principle of clinical equipoise should apply in the humanitarian setting as in any other, making randomized controlled trials (RCTs) the most ethical way to conduct research in this situation, using the recent Ebola outbreak and subsequent drug trials to illustrate their point [51]. With respect to Ebola, Perez et al. make the claim that, given the lethality of the disease, not including pregnant women and children (two groups often excluded from trials on grounds of inherent vulnerability) in Ebola trials is unethical [46]. This, however, presupposes a benefit to the experimental arm of a hypothetical trial, which would violate the principle of clinical equipoise and thus Lanini et al.’s justification of clinical trials outlined above [51]. Salerno et al. argue that the unique circumstances of conducting research in humanitarian settings necessitates that the researcher be less stringent in terms of study design. As the authors explain, “the recipients of experimental interventions, locations of studies, and study design should be based on the aim to learn as much as we can as fast as we can without compromising patient care or health worker safety, with active participation of local scientists, and proper consultation with communities” [52].

Again, with a focus on the recent Ebola outbreak, Calain makes an argument that insistence on RCTs, in which, by definition, one group of participants will be denied the experimental treatment, equates to a preference toward a collective interest (i.e. societal) over the individual (i.e. the patient) which could violate the basic principle of beneficence [53]. For Calain, in the face of a catastrophic illness like Ebola, randomization of interventions is seen as a “tragic choice” for humanitarian workers [53]. Furthermore, as Schopper et al. explained, there is justifiable concern that clinical trials during such an epidemic, which require significant amounts of resources and planning, would detract from the crucial work of directly caring for patients in a resource limited setting [29].

Informed consent

Like formal ethical review, informed consent is another core component of modern research ethics and was separately discussed in ten articles [21,22,23, 27, 37, 38, 44, 46, 65, 66]. Our results highlight several unique considerations when contemplating informed consent in humanitarian settings. For example, Western norms of written consent might be impossible if research is carried out in a population with low literacy rates or when written consent can violate the need for complete anonymity or expeditious research [21, 22, 44]. Controversy surrounding traditional ideas of informed consent were highlighted by Chiumento et al. in their literature review [22]. The authors explain that despite the general consensus that informed consent was central to ethical research, there were some authors who emphasized a more informal process that considered “consent as a partnership between researchers and participants” [22]. Some authors surveyed in the study supported flexibility in informed consent by utilizing a “consent framework” that presumably ensures norms such as autonomy and capacity, but allows some latitude for the researcher to adapt to the circumstances. Germane to this point is what Black et al. describe as “dynamic consent”—where a participant’s willingness to be involved in a project is constantly reassessed [44].

Chiumento et al. explain that because of cultural norms, the typical processes of consent may be undesirable or even impossible [21]. In their case study of research conducted in a post-conflict setting in South Asia, they explain that the procurement of informed consent first required permission from gatekeepers (i.e. household males and village elders) [21]. They outline the concept of negotiated consent in which collaboration with researchers helps to distil what exactly culturally specific consent would look like and proceed with an ad-hoc consent process [21].

Our results suggest that special attention be paid to informed consent during clinical trials conducted in the humanitarian setting [29, 46, 51]. Particularly illustrative is the idea of informed consent for experimental therapies during the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014–2015 [46]. Authors raise the question as to whether or not informed consent, free of coercion, can really be possible when potential subjects are faced with such a deadly disease [23].

The use of participatory visual methods (PVM) poses specific challenges with regard to informed consent. The methods ask researchers to encourage subjects to engage in creative forms of communication and expression, such as drama, photography, film, drawing, design, creative writing and music. The products can then be used to engage the community and answer research questions.

However, as participants are synthesizing novel content during the study, and are often encouraged to draw on traumatic experiences as inspiration for this content, fully informed consent is impossible. This is because neither participants nor investigators can completely anticipate which direction their facilitated creative endeavors might turn [44, 65]. This type of research may require more creative or dynamic forms of consent such as frequent check-ins with participants, or “dynamic consent”, as described above.

Cultural considerations

The importance of strong appreciation, humility, and understanding of local culture was discussed to a robust degree in six articles [21, 47, 50, 57, 64, 67]. As Black et al. explain, research can only be legitimate if it accepts the people as central actors [57]. They describe how community and cultural dynamics may be vital to ensuring that the products of research not be utilized in perverse ways [57]. The authors explain that analyzed and interpreted data on a particular population could be of strategic value to belligerents in a conflict setting [57]. This notion presents an obvious ethical challenge as it has the potential to make researchers active participants in conflict or surveillance. One may conclude that the solution is for researchers to refuse to share data with any local authorities. This, however, conflicts with what Ditton et al. refer to as a vital aspect of ethical field research, namely “the importance that the researcher has an appropriate relationship with the legitimate gatekeepers [and policy makers] of a field site” [47]. As the authors note, local authorities may have perfectly legitimate reasons for demanding cooperation and transparency from researchers. For example, in Thailand, government control of researchers might be justifiable since they espouse it as necessary to ensure that the local population is the ultimate beneficiaries of the research produced within their communities. The government, being responsible for the public’s well-being, argues that having some control over research activities is necessary for them to meet this responsibility [47].

Despite general agreement about the importance of respect for local customs, there is more ambivalence toward which, if any, customs might justifiably be ignored. Bennouna et al. in their survey of researchers explain that 15% of respondents did not believe that local attitudes should be taken into account when deciding on including children in a study, because “what if they tell us not to listen to children?” implying that local norms should not preclude children from having a right to be heard [67]. In contrast, Chiumento et al. suggest “that ethical conduct of research does not equate to importing cultural norms.” The authors continue to describe a common “ethically charged dilemma” in which consent or access to participants first requires permission from a “gatekeeper.” Cultural norms may dictate that (often male) household or community leaders are to make decisions in terms of participation and access to research, depriving some members of the community of basic “ethic and human rights norms” such as autonomy and the right to participate or refuse [21]. These points highlight an unanswered question regarding the universality of ethical principles.

Not only might respect for cultural norms be inherently ethically desirable, but it may also be important for ensuring community participation. As Mfutso-Bengo et al. explain, respect for cultural norms may be necessary “to ensure active community involvement as the community does not perceive overt threats to their way of life” [50]. Balancing fundamental ethical principles of inclusion and autonomy with cultural norms, the articles agree, requires deep cultural understanding.

Risks to researchers

Five of our included articles discuss the potential risk to researchers working in a humanitarian setting [21, 23, 49, 68, 69]. With the inherent instability of many of these contexts, Chiumento et al. summarize the wide range of potential risks to the wellbeing of researchers, stating that “threats to physical safety; risk of psychological distress; potential for accusations of improper behavior; and increased exposure to everyday risks such as infectious illnesses or accidents” must be recognized [21]. The very nature of conducting research in disaster settings exposes researchers to the potential of witnessing “human carnage and physical destructiveness” [23]. While researchers have personal decision-making responsibilities, host organizations must also acknowledge their obligations to provide security and mitigate risks while ensuring the researchers are fully informed of potential dangers [23, 69].

Child participation

Child participation in research was discussed in four articles [43, 65, 67, 70]. There was a general consensus that despite being particularly vulnerable, researchers had an ethical responsibility to include children in their studies. This action is necessary, the authors conclude, in order to ensure that children’s voices are heard and that they are not excluded from potential benefits of the research [67].

D’Amico et al. explain “researchers need to develop specific approaches that ensure children understand the benefit of participating voluntarily in research and that consent is informed and an ongoing process” [65]. The challenge, however, as the authors explain, is that through research, particularly qualitative forms such as PVM, “dangerous emotional terrain” might be breeched [65]. The implication is that it is difficult to know whether anyone can fully consent to these unforeseen emotional responses, especially children.

Data ownership

Two articles describe the unique ethical concerns surrounding data ownership when conducting research in the humanitarian setting [45, 57]. Often, none of the researchers in question are from the communities being studied, so the potential ethical pitfalls of an abusive extractive nature of data collecting might be created [45]. The concern arises when researchers from high-income countries collect data on lower income communities and the ultimate benefits are seen in the former [57].

Mental health

Mental health research, which was discussed in two articles, has some unique features, which create special ethical issues [21, 22]. For example, Chiumento et al. describe how community mistrust, stigma and paranoia can be particularly significant with regard to mental health, complicating mental health research [21]. There is also a particular importance for confidentiality and anonymity during mental health research given the potential for discrimination and stigmatizing behavior [22].

Discussion

With the drive toward professionalization of humanitarian practice comes a need to develop a strong evidence base. While the latter half of the twentieth century has seen promising trends in favor of ethical standards for research, the unique conditions of humanitarian work and the particular vulnerabilities of the communities being studied makes exploration of humanitarian research ethics imperative. The time-sensitive nature of the work in combination with complex cultural and security dynamics makes conducting research in the humanitarian setting inherently difficult from an ethical perspective.

Efforts to better understand the nexus between research and humanitarian emergencies are expanding. Other research, including an ongoing review of ethics of humanitarian research and more focused analyses of ethics among specific crises will service to expand this knowledge base [72]. We hope that this paper, representing a broad review and meta-ethnographic analysis of ethical issues in research over more than two decades, strengthens ethical processes and decision making in the humanitarian sector.

Among the 52 articles included in the analysis, 10 major themes regarding the ethics of humanitarian research were extracted for future analysis. In our qualitative analysis of the articles, we found a general acceptance by authors that the increased vulnerabilities of crisis-affected populations lead to several unique issues. Though identified and described in our search, many of these issues have yet to be adequately resolved in a way that might be useful to further researchers. For example, with regard to respect for local cultural norms, our results highlight a unique conflict between a cultural or political demand to share research with a local authoritative body and moral or ethical apprehensions to do so [47, 57]. Authors identified both acceptable and unacceptable reasons for an authoritative body to demand access to research [47, 57]. The researcher must then decide whether they cooperate with authorities by sharing products of their research, and risk being complicit in less socially desirable actions, or refuse and risk access to their study population, potentially depriving them of the fruits of their work. And to the related point embodied in the disagreement between MSF-Belgium and Rennie, controversy persists as to whether cooperating with an authoritative body to study a practice in which they are engaged suggests support of that practice [55, 63]. Further exploration of these questions is essential as the role of research on humanitarian response expands.

Our results suggest that themes of cultural considerations, community engagement and mental health research incorporate ethical dilemmas related to cultural relativism. Accepting cultural norms such as gaining a husband’s consent for his wife’s participation in a research study, or excluding children from a research project on the grounds that including them is too high risk, equates to denying some of the fundamental principles of ethical research. Therefore, researching these populations may mean conceding to certain undesirable cultural norms and rejecting others that would require the researcher to compromise ethical standards. But where should the line be drawn? What guiding principles can future researchers employ? Bennouna et al.’s survey, which revealed most researchers claimed they would, if necessary, ignore local customs and include a child’s point of view in a study might help answer the question [67]. More of this type of research needs to be done in order to identify and resolve potential conflicts of local norms and traditional research ethics.

A surprising result of our study was that some researchers held the view that certain components of traditional, modern research ethics, such as formal consent, may be applied less rigidly in the humanitarian setting [21, 22, 44]. For example, arguments have been made that any consent is impossible in the case of experimental treatment for Ebola victims, and the failure to meet traditional standards should not preclude one from conducting this research [52]. On the other hand, there may be certain universal ethical principles of conducting research that should never be compromised. Exactly which principles these are, if any, have yet to be elucidated.

There are further unanswered questions with regard to the involvement of local institutions. Though our results point to a general agreement about the magnanimity of significant local involvement in research, including the development of local capacity for such work the inherent challenges have yet to be addressed [27, 33]. Humanitarian research is often conducted in places with little or no infrastructure and limited numbers of qualified researchers. Including local aid workers as researchers, solely for the inherent value of doing so, may prove costly and distract from other research mandates and aid delivery, particularly in disaster relief. As Tansey et al. put it, “while the global health research literature strongly endorses community engagement in all research, there have been few suggestions for overcoming challenges to carrying it out in the disaster setting” [33]. Future work must come to terms with this inevitable conflict of ideals.

Despite the unavoidable ethical challenges, the results of this systematic review suggest that not only is it possible to conduct research in this context, but there is an ethical obligation to do so [41, 48]. If the global community is compelled to provide assistance in the form of humanitarian action, than those in the humanitarian field must acknowledge the responsibility to develop rational, evidence-based approaches that are, at their core, ethically responsible [41]. This impulse is reflected in our results, which demonstrate an increasing number of publications on humanitarian research ethics since the inception of the Sphere project. The growing body of literature bodes well for researchers looking to ground their future work in a strong ethical foundation.

We would like to note, however, that the vast majority of articles included in this study were from high-income and Western countries. This highlights a finding in the research itself—that community participation and involvement of researchers from the countries and regions affected by crisis is limited. Addressing this inequity should be prioritized as the field of humanitarian research ethics progresses.

It should be noted that our study has limitations. We attempted to conduct a comprehensive review of the literature with a systematic review, augmented by known grey literature, but may have missed some potentially relevant literature that did not fit the search terms and was not identified via the grey literature review. This review is based primarily on published research literature and may exclude operational or programmatic reports with valuable insights. Also, though our initial search did include book chapters via the Scopus database, and dozens of chapters have been written on the subject, relatively few were screened into our final list of included literature. The reason for this is not immediately apparent. The authors did note a relative difficulty in the searching for and screening of book chapters when compared with other types of articles. This may have lead to a preferential selection of the latter type of literature, at the expense of the former.

The selection of papers was systematic and reproducible, and the analysis of those papers relied on standard qualitative methods. While the analysis may be considered less reproducible, we utilized a standardized interpretive methodology that would reliably highlight the critical findings and points within the papers as evidenced by the strong consensus between the authors (WB and RH) on almost every inclusion and exclusion decision. Though the limited literature base makes drawing firm conclusions difficult, the consistency of issues raised between and within the articles confirms the importance of the major themes elicited in this analysis.

Conclusion

This study represents one of only very few attempts at a systematic review of research ethics in the humanitarian setting. We identified an increase in articles with robust ethical discussions particularly in the past few years. This promising trend could lead to further clarification and stronger ethical grounding of future research. Our data also highlight a number of unanswered questions related to fundamental conflicts that are unique to conducting research in the humanitarian setting. There is a clear need for further research and debate addressing these, and other important questions, such as: When is it appropriate to share data with local authorities? At what point should a researcher abandon a cultural relativistic point of view for an absolutist one? In a modern day humanitarian setting, what components of traditional ethics review may be anachronistic? How can researchers include local stakeholders as co-investigators when they may lack the training or infrastructure to do so? Mechanisms to translate these discussions into practical guidelines will need to be strengthened if the ideals of the Sphere Project are to be realized.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available as tables in the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ERB:

-

Ethical Review Board

- LMIC:

-

Low and Middle Income Countries

- MSF:

-

Médecins Sans Frontières

- RCT:

-

Randomized Clinical Trial

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Global Humanitarian Overview. United Nations Coordinated Support to Pepole Affected by Disaster. 2019 https://www.unocha.org/sites/unocha/files/GHO2019.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2020.

UNHCR - Yemen emergency. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/yemen-emergency.html. Accessed 31 Jan 2019.

WHO Bangladesh Rohingya crisis. Word Health Organization. 2019. https://www.who.int/emergencies/crises/bgd/en/. Accessed 31 Jan 2019.

Rysaback-Smith H. History and principles of humanitarian action. Turkish J Emerg Med. 2015;15(Suppl):5–7.

Davey E, Borton J, Foley M. A history of the humanitarian system Western origins and foundations. 2013. https://www.odi.org/publications/7535-history-humanitarian-system-western-origins-and-foundations. Accessed 15 Feb 2020.

Eriksson J, Adelman H, Borton J, Christensen H, Kumar K, Suhrke A, et al. The international response to conflict and genocide: lessons from the Rwanda experience synthesis report joint evaluation of emergency assistance to Rwanda. Organisation for economic co-operation and development. 1996. https://www.oecd.org/countries/rwanda/50189495.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2020.

Buchanan-Smith M. How the Sphere Project Came into Being: A Case Study of Policy-Making in the Humanitarian Aid Sector and the Relative Influence of Research. 2003. Overseas Development Institute. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/176.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2020.

Blanchet K, Ramesh A, Frison S, Warren E, Hossain M, Smith J, et al. Evidence on public health interventions in humanitarian crises. Lancet. 2017;390(10109):2287–96.

Reverby SM. Ethical failures and history lessons: the U.S. Public Health Service research studies in Tuskegee and Guatemala. In: Public Health Reviews. 2012. https://publichealthreviews.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1007/BF03391665. Accessed 15 Feb 2020.

Hunt M, Schwartz L, Pringle J, Boulanger R, Nouvet E, O’Mathúna D, et al. A research agenda for humanitarian health ethics. PLOS Curr. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1371/currents.dis.8b3c24217d80f3975618fc9d9228a144.

Hunt M, Tansey CM, Anderson J, Boulanger RF, Eckenwiler L, Pringle J, et al. The challenge of timely, responsive and rigorous ethics review of disaster research: views of research ethics committee members. PLoS One. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157142.

The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. 1978. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/read-the-belmont-report/index.html.

Broussard G, Rubenstein LS, Robinson C, Maziak W, Gilbert S, DeCamp M. Challenges to ethical obligations and humanitarian principles in conflict settings: a systematic review. Int J Humanitarian Action. 2019;4:15.

Ethics in Complex Humanitarian Emergencies: Summary of a Workshop. National Research Council (US) Roundtable on the Demography of Forced Migration. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2002.

Leaning J, Guha-Sapir D. Natural Disasters, Armed Conflict, and Public Health. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1836–42.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and Meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1988.

MacEachen E, Clarke J, Franche R-L, Irvin E, Workplace-based Return to Work Literature Review Group. Systematic review of the qualitative literature on return to work after injury. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32:257–69.

Campbell R, Pound P, Pope C, Britten N, Pill R, Morgan M, et al. Evaluating meta-ethnography: a synthesis of qualitative research on lay experiences of diabetes and diabetes care. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:671–84.

Britten N, Campbell R, Pope C, Donovan J, Morgan M, Pill R. Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: a worked example. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002;7:209–15.

Chiumento A, Khan MN, Rahman A, Frith L. Managing ethical challenges to mental Health Research in post-conflict settings. Dev World Bioeth. 2016;16:15–28.

Chiumento A, Rahman A, Frith L, Snider L, Tol WA. Ethical standards for mental health and psychosocial support research in emergencies: review of literature and current debates. Glob Health. 2017;13:41.

O’Mathúna DP. Conducting research in the aftermath of disasters: ethical considerations. J Evid Based Med. 2010;3:65–75.

Eckenwiler L, Pringle J, Boulanger R, Hunt M. Real-time responsiveness for ethics oversight during disaster research. Bioethics. 2015;29:653–61.

Falb K, Laird B, Ratnayake R, Rodrigues K, Annan J. The ethical contours of research in crisis settings: five practical considerations for academic institutional review boards and researchers. Disasters. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12398.

Packenham JP, Rosselli RT, Ramsey SK, Taylor HA, Fothergill A, Slutsman J, et al. Conducting science in disasters: Recommendations from the NIEHS working group for special IRB considerations in the review of disaster related research. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125:094503.

O’Mathúna D. Research ethics in the context of humanitarian emergencies. J Evid Based Med. 2015;8:31–5.

O’Mathúna D, Siriwardhana C. Research ethics and evidence for humanitarian health. Lancet. 2017;390:2228–9.

Schopper D, Ravinetto R, Schwartz L, Kamaara E, Sheel S, Segelid MJ, et al. Research ethics governance in times of Ebola. Public Health Ethics. 2017;10:49–61.

Folayan MO, Peterson K, Kombe F. Ethics, emergencies and Ebola clinical trials: the role of governments and communities in offshored research. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;22:10.

Schopper D, Dawson A, Upshur R, Ahmad A, Jesani A, Ravinetto R, et al. Innovations in research ethics governance in humanitarian settings. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16:10.

Saxena A, Horby P, Amuasi J, Aagaard N, Köhler J, Gooshki ES, et al. Ethics preparedness: facilitating ethics review during outbreaks - recommendations from an expert panel. BMC Med Ethics. 2019;20:29.

Tansey CM, Anderson J, Boulanger RF, Eckenwiler L, Pringle J, Schwartz L, et al. Familiar ethical issues amplified: how members of research ethics committees describe ethical distinctions between disaster and non-disaster research. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18:44.

Chan EYY, Wright K, Parker M. Health-emergency disaster risk management and research ethics. Lancet. 2019;393:112–3.

Mezinska S, Kakuk P, Mijaljica G, Waligóra M, O’Mathúna DP. Research in disaster settings: a systematic qualitative review of ethical guidelines. BMC Med Ethics. 2016;17:62.

Richardson T, Johnston AMD, Draper H. A systematic review of Ebola treatment trials to assess the extent to which they adhere to ethical guidelines. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0168975.

Hussein G, Elmusharaf K. Mention of ethical review and informed consent in the reports of research undertaken during the armed conflict in Darfur (2004-2012): a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics. 2019;20:40.

Alirol E, Kuesel AC, Guraiib MM, de la Fuente-Núñez V, Saxena A, Gomes MF. Ethics review of studies during public health emergencies - the experience of the WHO ethics review committee during the Ebola virus disease epidemic. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18:43.

Aarons D. Research in epidemic and emergency situations: a model for collaboration and expediting ethics review in two Caribbean countries. Dev World Bioeth. 2018;18:375–84.

Bain LE, Ngwain CG, Nwobegahay J, Sumboh JG, Nditanchou R, Awah PK. Research ethics committees (RECs) and epidemic response in low and middle income countries. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;31:209.

Banatvala N, Zwi AB. Public health and humanitarian interventions: developing the evidence base. BMJ. 2000;321:101–5.

Shanks L, Moroni C, Rivera IC, Price D, Clementine SB, Pintaldi G. “Losing the tombola”: a case study describing the use of community consultation in designing the study protocol for a randomised controlled trial of a mental health intervention in two conflict-affected regions. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16:38.

Betancourt T, Smith Fawzi MC, Stevenson A, Kanyanganzi F, Kirk C, Ng L, et al. Ethics in Community-Based Research with Vulnerable Children: Perspectives from Rwanda. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157042 Burns JK, editor.

Black GF, Davies A, Iskander D, Chambers M. Reflections on the ethics of participatory visual methods to engage communities in global health research. Glob Bioeth. 2018;29:22–38.

Boyce R, Rosch R, Finlayson A, Handuleh D, Walhad SA, Whitwell S, et al. Use of a bibliometric literature review to assess medical research capacity in post-conflict and developing countries: Somaliland 1991-2013. Tropical Med Int Health. 2015;20:1507–15.

Carazo Perez S, Folkesson E, Anglaret X, Beavogui A-H, Berbain E, Camara A-M, et al. Challenges in preparing and implementing a clinical trial at field level in an Ebola emergency: A case study in Guinea, West Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005545 Schibler M, editor.

Ditton MJ, Lehane L. The control of foreigners as researchers in Thailand. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2009;4:49–57.

Ford N, Mills EJ, Zachariah R, Upshur R. Ethics of conducting research in conflict settings. Confl Health. 2009;3:7.

Funk KL, Rayes D, Rubenstein LS, Diab NR, DeCamp M, Maziak W, et al. Ethical Challenges Among Humanitarian Organisations: Insights from the Response to the Syrian Conflict. In: Humanitarian Action and Ethics. London: Zed; 2018.

Mfutso-Bengo J, Masiye F, Muula A. Ethical challenges in conducting research in humanitarian crisis situations. Malawi Med J. 2008;20:46–9.

Lanini S, Zumla A, Ioannidis JPA, Di Caro A, Krishna S, Gostin L, et al. Are adaptive randomised trials or non-randomised studies the best way to address the Ebola outbreak in West Africa? Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:738–45.

Salerno J, Hlaing WM, Weiser T, Striley C, Schwartz L, Angulo FJ, et al. Emergency response in a global health crisis: epidemiology, ethics, and Ebola application. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26:234–7.

Calain P. The ebola clinical trials: a precedent for research ethics in disasters. J Med Ethics. 2018;44:3–8.

Rid A. Individual and public interests in clinical research during epidemics: a reply to Calain : in response to: Calain P. the Ebola clinical trials: a precedent for research ethics in disasters. J Med Ethics. 2018;44:11–2.

Rennie S. Is it ethical to study what ought not to happen? Dev World Bioeth. 2006;6:71–7.

London AJ. Social value, clinical equipoise, and research in a public health emergency. Bioethics. 2019;33:326–34.

Black R. Ethical codes in humanitarian emergencies: from practice to research? Disasters. 2003;27:95–108.

Contractor Q. Fieldwork and social science research ethics. Indian J Med Ethics. 2008;5:22–3.

Jacobsen K, Landau LB. The dual imperative in refugee research: some methodological and ethical considerations in social science research on forced migration. Disasters. 2003;27:185–206.

Pringle JD, Cole DC. Health Research in complex emergencies: a humanitarian imperative. J Acad Ethics. 2009;7:115–23.

Wessells M. Reflections on ethical and practical challenges of conducting research with children in war zones: toward a grounded approach. In: Mazurana D, Jacobsen K, Gale L, editors. Research methods in conflict settings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011. p. 81–105.

Wood EJ. The ethical challenges of field research in conflict zones. Qual Sociol. 2006;29:373–86.

Zachariah R, Janssens V, Ford N. Do aid agencies have an ethical duty to comply with researchers? A response to Rennie. Dev World Bioeth. 2006;6:78–80.

Jesus JE, Michael GE. Ethical considerations of research in disaster-stricken populations. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2009;24:109–14.

D’Amico M, Denov M, Khan F, Linds W, Akesson B, et al. Research as intervention? Exploring the health and well-being of children and youth facing global adversity through participatory visual methods. Glob Public Health. 2016;11:528–45.

Aarons D. Addressing the challenge for expedient ethical review of research in disasters and disease outbreaks. Bioethics. 2019;33:343–6.

Bennouna C, Mansourian H, Stark L. Ethical considerations for children’s participation in data collection activities during humanitarian emergencies: a Delphi review. Confl Health. 2017;11:5.

Mneimneh ZN, Axinn WG, Ghimire D, Cibelli KL, Alkaisy MS. Conducting surveys in areas of armed conflict. In: Tourangeau R, Edwards B, Johnson TP, Wolter KM, Bates N, editors. Hard-to-survey populations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2014. p. 134–56.

Ethical Challenges in Humanitarian Health in Situations of Extreme Violence . Center for Public Health and Human Rights, Center for Humanitarian Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. 2019. http://hopkinshumanitarianhealth.org/assets/documents/LR_XViolenceReport_2019_final.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2020.

Ferreira RJ, Buttell F, Cannon C. Ethical issues in conducting research with children and families affected by disasters. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20:42.

Leaning J. Ethics of research in refugee populations. Lancet. 2001;357(9266):1432–3.

Martin S, Abd-Elfarag G, Kuhn I, Van Bortel T, Doherty S, O’Mathuna D. A systematic review of the ethical issues in humanitarian health research. International prospective register of systematic reviews. 2018. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php? RecordID=84470. Accessed 9 Dec 2019.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Parveen Parmar and Len Rubenstein for support in developing the conceptual framework of this study.

Funding

There was no funding for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WB was primarily responsible for writing the manuscript and co-coordinated study design, data analysis, and data interpretation and contributed to data collection. RH designed the study, contributed to data analysis, data interpretation, and writing. All authors have reviewed the submitted manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This review of published literature did not require ethical review.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1.

PRISMA Checklist.

Appendix

Appendix

Search terms for systematic review of humanitarian research ethics

-

1.

(Humanitarian OR “Global health”) AND (disaster OR emergency OR conflict) AND (ethic* OR bioethic* OR “human rights” OR rights) AND (research OR “program evaluation” OR “monitoring and evaluation” OR investigation) [MeSH terms].

-

2.

(disaster) AND (ethic* OR bioethic* OR “human rights” OR rights) AND (research OR “program evaluation” OR “monitoring and evaluation” OR investigation) [MeSH terms]. Disaster medicine/ [MeSH]

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bruno, W., Haar, R.J. A systematic literature review of the ethics of conducting research in the humanitarian setting. Confl Health 14, 27 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-020-00282-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-020-00282-0