Abstract

Burning Mouth Syndrome (BMS), a chronic intraoral burning sensation or dysesthesia without clinically evident causes, is one of the most common medically unexplained oral symptoms/syndromes. Even though the clinical features of BMS have been astonishingly common and consistent throughout the world for hundreds of years, BMS remains an enigma and has evolved to more intractable condition. In fact, there is a large and growing number of elderly BMS patients for whom the disease is accompanied by systemic diseases, in addition to aging physical change, which makes the diagnosis and treatment of BMS more difficult. Because the biggest barrier preventing us from finding the core pathophysiology and best therapy for BMS seems to be its heterogeneity, this syndrome remains challenging for clinicians. In this review, we discuss currently hopeful management strategies, including central neuromodulators (Tricyclic Antidepressants - TCAs, Serotonin, and Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors - SNRIs, Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors - SSRIs, Clonazepam) and solutions for applying non-pharmacology approaches. Moreover, we also emphasize the important role of patient education and anxiety management to improve the patients’ quality of life. A combination of optimized medication with a short-term supportive psychotherapeutic approach might be a useful solution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

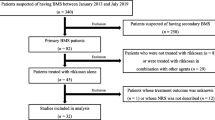

Burning Mouth Syndrome (BMS), also called “stomatodynia” or “glossodynia”, is one of the most common medically unexplained oral symptoms/syndromes (MUOS) [1, 2]. Over centuries, a large number of BMS studies have been conducted about the pathophysiology [3,4,5], but so far with limited knowledge because of its heterogeneity [6, 7]. Although the clinical features of BMS have been astonishingly common and consistent throughout the world for hundreds of years, an ultimate treatment strategy has not been established [8,9,10,11]. At the Department of Psychosomatic Dentistry, Dental Hospital, Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU), Japan, we have around 250 new BMS patients every year and currently treat 4–5000 outpatients. Among them, approximately 55% are over 65 years old. Because the majority of elderly patients are accompanied by systemic diseases and contraindications of tricyclic antidepressant, the first line in management of BMS, the population aging poses challenges in patient management [12]. (Fig. 1) The actual situation makes the diagnosis and treatments of BMS more complex and difficult. A recent study in the United Kingdom shows the profound financial impact of persistent orofacial pain on patients’ lives, in which the ‘hidden economical-social cost’ was calculated around 3000 GBP (Great Britain Pound) per year [13]. It has attracted attention and controversy as to HOW we should manage this syndrome in the elderly[14]. In this review, we discuss real-world, useful strategies for the management of patients with BMS, especially the elderly.

Overview of burning mouth syndrome

Definition

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) presents BMS as “a chronic condition characterized by a burning sensation of the oral mucosa for which no cause can be found” [1]. The International headache society (IHS) defines BMS as “an intraoral burning sensation or dysesthesia, recurring daily for more than 2 hours per day over more than 3 months, without clinically evident causative lesions” [15]. This definition concretely shows the duration of daily and consecutive symptoms, thus it was preferred for use in diagnosis. The common finding among the definitions of BMS is the involvement of no obvious clinical causative lesions. However, the term BMS is sometimes used to describe an oral burning sensations that is induced by several local or systemic conditions, also called “secondary” BMS, instead of an “exact” oral pain/dysesthesia condition with unknown origin or “primary” BMS. This inconsistency indicates that although the diagnostic criteria for BMS have become more sophisticated they remain a little rough. They can include many causative factors and heterogeneous patients, because of the lack of accurate biomarkers and little knowledge of pathophysiology [7, 16].

Epidemiology

There are several epidemiology studies that include “secondary” BMS while only a few are conducted on “exact” BMS. Overall, the prevalence of BMS in the adult population has been reported to be between 0.7 and 3.7% [17, 18]. The syndrome usually occurs in middle-aged and elderly patients more often than in children and adolescents, and female predominance has been reported (female: male = 7:1) [19]. The relevance of psychiatric disorders in BMS is remains to be clarified, but one study reported that about 50% of BMS patients have specific psychiatric diagnoses, 60% of whom are diagnosed with mood disorders [20]. Overlap with other MUOS (atypical odontalgia, phantom bite syndrome, oral cenesthopathy) should be also carefully considered. BMS is sometimes comorbid with atypical odontalgia in the same patient, which contributes to a more intensively painful experience [21].

Pathophysiology

BMS is a syndrome of unknown causes for which the etiology and pathological origin are under debate [7, 16]. Patients often have been regarded as having psychogenic conditions [22]. Although many attempts have been made to clarify the relation between BMS and psychological factors, the relation remains unclear [20, 23, 24].

The majority of BMS patients are postmenopausal women, thus the association with female hormones has been proposed [25]. Furthermore, a study reported that because BMS patients frequently suffer from taste disturbance and other similar problems, dysfunction of the chorda tympani nerve may be involved [26]. Other researchers support the hypothesis that BMS may be a neuropathic pain involving the central nervous system [4, 9, 27]. It is probably true that some central sensitization might be related to BMS, as are other functional somatic syndromes [28, 29], however, recent evidence shows its limitations, especially for elderly patients [30, 31]. In addition, the pathophysiology should be considered not only as a pure painful sensation but also as oral discomfort that includes dysgeusia and subjective dry mouth [32, 33], which seems to be more common in the elderly.

In this review, we assume that the etiology and pathophysiology of BMS might not be that simple, but rather a complex, multifactorial condition. BMS symptoms seem to represent something of an amalgam of various factors in the same patient. (Fig. 2) From a clinical viewpoint, the efficacy of some antidepressants [2, 3, 5, 9,10,11] might be the best evidence showing the relation to dysregulation of some neurotransmitters, including dopamine nervous systems [7], which probably affect complex neurological networks [29]. In future study, neuroimaging will play a promising, key-role in clarifying the mechanisms of the central nervous system [34,35,36,37].

Diagnosis based on clinical features

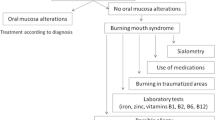

The diagnosis of BMS remains challenging because it shares symptoms with several conditions, such as Candida infection, allergy, or nutritional deficiency. In real-life clinical situations, instead of using the classification-based criteria of ICHD or IASP clinicians usually do differential diagnosis to rule out other possible related conditions [3, 10, 11]. To address how to do more precise BMS diagnosis, we suggest in this review that some classical clinical features be added to the official criteria proposed by ICHD and IASP. (Table 1) These clinical features of BMS might be helpful for decreasing the time to diagnosis and improving accuracy.

Our clinical routine usually starts with a review of the medical history, examining extra/intra oral findings, and checking the consistency of subjective symptoms. (Table 1) Then, we perform a general medical examination, do blood tests and salivary measurement, do imaging such as MRI, and CT scan, and give psychological questionnaires [3, 6]. While taking care of elderly patients, who often have multiple systemic diseases and take numerous kinds of medications in addition to experiencing normal physical change from aging, clinicians should be aware of the possibility of underlying malignant tumors (Fig. 3) and dementia [38]. After checking for the above, the final diagnose depends mainly on the patients’ subjective symptoms and history. Most of the complaints of BMS patients’ are focused on their tongue, usually a tingling/burning/numbing sensation or feeling [27]. Symptoms related to the palate, lip, or gingiva are also observed, however, facial skin is not usually affected. Symptoms are often relieved by having a food like chewing gum or candy in the patient’s mouth, and they worsen throughout the day [3].

There are several comorbid oral symptoms other than pain, such as dry mouth and taste disturbance [6]. In addition, BMS has been linked with psychological factors, including stress, depression and anxiety [39]. Cancerophobia, a type of anxiety disorder, was more frequently seen in patients with BMS than in those with other types of orofacial pain [40]. This hints that the “pain” of BMS involves some qualities that evoke life-threatening emotion or restlessness in the patient. Like with other MUOS, BMS patients often do medical institution shopping, but usually are found to have no abnormal findings and thus experience strong frustration. Because of this shopping, delays in the diagnosis of BMS and referral to an appropriate medical institution were frequently reported [41].

A dilemma in the management of burning mouth syndrome

The management of BMS had been said to be like a ‘jumble of wheat and chaff,’ [42, 43] with little evidence to support or refute the various interventions [44,45,46]. Moreover, there are “too many reviews and too few trials,” [47] which results in difficulty in choosing the most appropriate approach to therapy for each patient with BMS.

It would be accurate to say that there is no all-powerful treatment that can be effective for all BMS patients, in light of the various underlying conditions. The heterogeneity of this syndrome is the biggest barrier to reaching the best therapy. The nature of BMS is that it is a syndrome that has several causative factors, including some of psychosomatic nature such as chronic pain [24]. Hence, the treatment response of patients differs depending on the predominant individual confounding pathological factors, such as neuropathic components, central sensitization, and psychiatric comorbidities. The problems are intertwined in such a complex way that treatment problems cannot be solved completely by a single therapy.

In addition, no sufficiently effective assessment tool for BMS remission is available. As stated by Albert Einstein, “Not everything that can be counted counts and not everything that counts can be counted” [48]. The suffering of BMS can hardly be explained in Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) scores. Nevertheless, BMS involves not only pure pain sensation but also dysesthesia, such as dryness or dysgeusia. Clinicians, therefore, should carefully consider what a patient claims to be “pain” [29]. To conclude, we need more qualitative assessment methods that provide insight into the patients’ experience of pain instead of depending only on VAS [49].

Like other chronic pain, the treatment outcome of BMS can be explained by placebo effects [50, 51]. In contrast with clinical data such as blood pressure and cell blood counts, VAS does not give precise measurements. With no gold-standard instrument, clinicians struggle to find alternative biomarkers and proper assessment tools for the diagnosis of this long-lasting, complex syndrome.

Another important problem is the assessment of duration and follow-up period [52]. BMS has continuous, long-lasting symptoms that often fluctuate. There is no reliable data on longitudinal outcome or recurrence in existing RCTs for BMS. Considering the nature of BMS, treatment outcome should be assessed after a sufficient period of observation. Retrospective, long-term treatment outcome may be a more critical option. We should observe and analyze the existing data to compare the past and present treatment outcomes in order to improve the patients’ function and quality of life (QoL) [53]. We suggest that real-world data may be more essential than short term RCTs to determine the benefits and limitations of a treatment regimen.

Currently hopeful treatment strategies

Even though there were many limitations mentioned above, we have high expectations for some treatments for BMS. The efficacy of central neuromodulators (Tricyclic Antidepressants - TCAs, Serotonin and Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors - SNRIs, Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors - SSRIs, Clonazepam) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) are supported by many studies [3, 9,10,11, 53, 54] and consistent with our clinical experience.

Central neuromodulators

In the 1970s, amitriptyline, a TCA, was used for BMS as the first line medication in Japan [53]. Response to TCA needed at least a few days and was not always certain, and side effects emerged quickly and often intensively. If the patients could feel slight improvement, even minor, they were willing to continue the medication and bear its side effects. However, unlike patients with classical trigeminal neuralgia, another type of persistent orofacial pain [13], who usually respond very well to carbamazepine, not all BMS patients can be treated with TCAs. It is important to emphasize here that antidepressants are not always a “magical bullet” for BMS, however, symptom relief could be achieved with careful prescription. Recent research suggests that a change of salivation and QTc interval in cardiology might predict treatment response to amitriptyline [55, 56].

Other than TCAs, SNRIs and SSRIs have shown potential in the treatment of BMS [5, 57,58,59]. However, they are not always sufficiently effective and some have characteristic side effects and drug interactions (withdrawal symptoms, a little different from TCA) and thus require special caution [60]. In general, the cost-effectiveness of TCA is probably better than SSRIs and SNRIs. Nevertheless, they are useful if their benefits and risks are carefully considered, especially for the elderly [61].

These weak points have inhibited the wide use of neuromodulators. Careful dosing and observation are critical to obtaining the best efficacy with the least side effects. A recent report on functional gastrointestinal disorders and non- gastrointestinal painful disorders recommended using a low to modest dosage of neuromodulators and provide the most convincing evidence of benefit [62], a finding similar to our clinical observation. Additionally, careful attention should be paid to cognitive impairment when long-term medication is provided to elderly patients. To cover these limitations, dopaminergic medications might be helpful in some cases [63, 64]. Nevertheless, they should not be prescribed easily [65].

In addition, Clonazepam - a kind of benzodiazepines (BZs) also used as an antiepileptic, might be a better option than TCAs [66]. It is often used as the first-line medication without severe side effects, except drowsiness, and the patient often feels better shortly. However, its effect usually is temporary, gradually decreases, and contains the risk of dependency, like other BZs. An oral rinse of Clonazepam had high expectations [67], however, in our clinical experience it seems to work successfully only at random. Also, for elderly patients the risk of falling and cognitive disturbances related to systemic BZ prescription must be seriously considered. For the same reason, gabapentinoids (Gabapentin and Pregabalin) should also be prescribed with caution [68].

Non-pharmacotherapeutic approaches

CBT is one of the effective treatments for burning mouth syndrome. Previous research has shown that the pain severity and discomfort of BMS were improved by CBT targeting cognitive factors [69, 70]. Although the treatment effects were very large and were maintained for 6 months to 12 months, 12 to 16 sessions are necessary to complete a CBT course, which makes it difficult to do for BMS patients due to its high treatment cost.

We recommend here three solutions for reducing the high cost of conducting CBT. The first is using a group format instead of an individual format. Previous research shows that CBT conducted as a form of group treatment and of short duration (1–2 sessions) improved the pain and anxiety of BMS patients [71]. Because no significant difference in effectiveness was shown in comparison with the individual format [72], CBT delivered as group format would be an effective, low-cost alternative solution.

The second solution for BMS patients is limiting the treatment content so that it focuses on specific characteristics. Recently, it was demonstrated that pain-related catastrophizing, a cognitive factor, influences pain severity and oral health-related QoL in BMS [73]. Pain-related catastrophizing maintains and exacerbates chronic pain, thus focusing on pain-related catastrophizing is an important aspect of treatment. Treatment focused on the amelioration of pain-related catastrophizing significantly improved the symptoms of BMS patients [74]. The treatment regimen used in this program consisted of four sessions, showing that CBT can be delivered with low cost by focusing on pain-related catastrophizing.

The third solution is limiting the techniques using in the treatment. Although CBT usually consists of multiple techniques, including psycho-education about disease and treatment and cognitive and behavioral techniques, a treatment regimen containing only psycho-education was shown to be successful for BMS [75]. In this psycho-education program, patients were provided various information about BMS, such as its characteristics, possible mechanisms, and treatment options including medications, which relieved the patients concern about the possible malignant nature of the condition. The importance of maintaining a normal lifestyle despite changes in their symptoms was emphasized. Delivering this extensive information was shown to improve BMS with low cost.

Sleep disorder is another important issue because it is frequently comorbid with BMS, with a prevalence of over 60% [76]. Sleep and chronic pain are bidirectional, thus pain can interfere with sleep and sleep disturbance can exacerbate pain [77]. This high prevalence of sleep disorder might lead to worsening of the symptoms of BMS. CBT-I, an effective treatment for sleep disorder, improved the sleep disturbance and pain symptoms of chronic pain patients [78]. Integrating CBT-I into the usual treatment for BMS would likely enhance the effectiveness of CBT for BMS patients.

Another issue involving BMS is adherence to medication. Although psychotropic medications are effective in the treatment of BMS, a high frequency of non-adherence was found in a population study of psychotropic medications [79]. In BMS, about 15% of the patients stop taking psychotropic medications [80]. These non-adherent patients could be helped by motivational interviewing, which is a CBT technique that can be used to enhance medication adherence [81].

For patients who cannot use any drugs, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (r TMS) may be effective [82, 83]. However, this approach needs an expensive, dedicated machine and requires much more time and effort in the clinic than do the usual pharmacotherapies. Another option is electro-convulsive therapy (ECT), which has shown beneficial results for severe and refractory cases with psychotic features, including a high risk of suicide [84, 85]. Fortunately, few patients are unable to use all of the potential medications, and for the few who can’t we recommend consultation with a psychiatrist.

Patient education and anxiety management without special therapies

Although CBT is a good option for the management of BMS management, specialist psychotherapists are not always available. Therefore, it is generally difficult to conduct orthodox therapy in the limited- space and time available in a real clinical situation [74]. More importantly, the effect of psychotherapy greatly depends on the capacity of the psychotherapist. Psychotherapy is especially difficult with older patients who have lost their mind plasticity [86].

Clinicians should not feel pressure to diminish all the symptoms of all their patients with BMS or to finish treatment quickly. We not only need to “manage” the symptoms of BMS, but also the improvement of the patients’ QoL. In the general clinical setting, a combination of optimized medication with a short-term supportive psychotherapeutic approach would be a promising solution [2, 53]. Successful disease management cannot be achieved only by pharmacology, but also needs effective communication to build a positive patient-doctor relationship [62].

First, clinicians should be cognizant of patient anxiety, which is not always at a psychopathological level. Patients are often unsettled by chronic oral pain/discomfort of unknown origin [41]. It is important to thoroughly rule out other medical conditions, especially malignancy. These ruling-out processes may relieve the patients’ anxieties and sometimes work as a kind of psychotherapy by themselves [75]. Plain and easy to understand explanation and reassurance that there is no malignancy are necessary. An accurate diagnosis of BMS may also play an important role in relieving a patient’s anxiety/fear of their symptoms. Finally, it can promote the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy of any kind.

Second, it is not always necessary and sometimes impossible to attempt to perfectly diminish pain at once. In a real clinical situation, recovery to normal life should be the priority achievement. “Normal life” does not mean an ideal life without any worries, but can be achieved when a patient can do almost everything necessary to their daily life without being bothered by slight oral symptoms. Even when 99% pain reduction is obtained, some patients continue to be annoyed by the minor residual pain and limit their daily activities. The pain and discomfort of BMS are of such a nature that they evoke emotional distress [21]. Clinicians must understand this characteristic nature of BMS suffering and explain and enhance the role of patients in the medication decision-making process [87] and repeatedly confirm the recovery process. It is also useful for recovery to their normal life to encourage the patient to continue sleep management [77] and adequate physical exercise, such as walking, according to their symptom reduction.

Additionally, the goal of treatment should be shared with patients as well as their family; and a prospective treatment course for BMS should be explained at the first visit to increase motivation for therapy, which can improve the prognosis. However, this is not always successful because of the rather wavelike, up and down, course of some patients’ symptoms. For instance, for some chronic pain patients with co-occurring persistent fatigue, over-predicting the goals in CBT probably leads to poor response [88]. Patients should be informed of the fact that BMS is an intractable pain condition, but that it is not hopeless to obtain complete remission in the future. It is important to choose an appropriate, feasible goal. Supportive understanding from the family is important for BMS patient to prevent discontinuation of treatment, especially so for the elderly. Like other chronic pain conditions, the management of BMS requires empathy, patience, and time from the clinicians, patients, and family.

Antidepressants have been shown to sometimes improve the BMS symptoms dramatically, within the first 5 - 7 days, after which the symptoms gradually improve for 1-2 months according to the dose, but perfect remission is not always reached [89]. After some improvement during early treatment, it is very disappointing and irritating for the patients to be confronted with the residual small waves of symptoms, which is no longer called “pain”. Dysgeusia, or subjective dry mouth, has a tendency to improve a little later than pain (burning sensation), so patients tend to complain more about dysesthesia than “pain” in the later period. (Fig. 4) According to our clinical experience, it usually takes minimum of 3–6 months for patients to get to a satisfactory condition and to stabilize. Thorough and careful tapering of the drugs may lead to a good ending of the pharmacotherapy.

Meaningful treatment goals should to be set on level of satisfaction patients will feel as they recover from pain that interferes with their lives and how to adjust to functional disabilities. The focus should not be on the scores of clinical measurements [49]. We should thoroughly understand these real responses to antidepressants for BMS without expecting a “miracle” recovery [89].

It is natural for a patient to feel anxiety about an unstable pain condition of unknown origin [39]. As above mentioned, adding a psychological component to the usual therapeutic regimen based on pharmacotherapy should be considered in the treatment of BMS. These processes are difficult to describe in the context of evidence-based medicine/dentistry.

In summary, BMS remains an enigma and has evolved into a more intractable condition, especially in the elderly. The diagnosis and treatment of BMS remains challenging. There are many problems with the existing treatment data on BMS, and long-term comprehensive assessment and outcome analysis are much needed. It is essential to maintain a supportive attitude to the patients and their family, assuring them of a good prognosis in the near future. Continuing psychological support and the careful use of antidepressants may help with the recovery of the brain function of these patients.

Abbreviations

- BMS:

-

Burning Mouth Syndrome

- BZs:

-

Benzodiazepines

- CBT:

-

Cognitive behavioral therapy

- ECT:

-

Electro-convulsive therapy

- IASP:

-

International Association for the Study of Pain

- IHS:

-

International headache society

- MUOS:

-

medically unexplained oral symptoms

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- SNRIs:

-

Serotonin and Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors

- SSRIs:

-

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

- TCAs:

-

Tricyclic Antidepressants

- TMS:

-

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

- VAS:

-

Visual Analogue Scale

References

Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of Chronic Pain. 2nd ed. Seattle, WA: IASP Press;. Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms;1994 p.74.

Toyofuku A. Psychosomatic problems in dentistry. Biopsychosoc Med. 2016;10:14.

Grushka M, Epstein JB, Gorsky M. Burning mouth syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65(4):615–20.

Forssell H, Jääskeläinen S, List T, Svensson P, Baad-Hansen L. An update on pathophysiological mechanisms related to idiopathic oro-facial pain conditions with implications for management. J Oral Rehabil. 2015;42(4):300–22.

Steele JC. The practical evaluation and management of patients with symptoms of a sore burning mouth. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34(4):449–57.

Patton LL, Siegel MA, Benoliel R, de Laat A. Management of burning mouth syndrome: systematic review and management recommendations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endo. 2007;103(suppl.39):S39.e1–S39.e13.

Jääskeläinen SK, Woda A. Burning mouth syndrome. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(7):627–47.

Périer JM, Boucher Y. History of burning mouth syndrome (1800-1950): a review. Oral Dis. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.12860.

Charleston L 4th. Burning mouth syndrome: a review of recent literature. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2013;17(6):336.

Gurvits GE, Tan A. Burning mouth syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(5):665–72.

Moghadam-Kia S, Fazel N. A diagnostic and therapeutic approach to primary burning mouth syndrome. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35(5):453–60.

Suga T, Watanabe T, Aota Y, Nagamine T, Toyofuku A. Burning mouth syndrome: the challenge of an aging population. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2018: Article in Press.

Breckons M, Shen J, Bunga J, Vale L, Study DJDEEP. Indirect and out-of-pocket costs of persistent orofacial pain. J Dent Res. 2018.

Yap T, McCullough M. Oral medicine and the ageing population. Aust Dent J. 2015;60(Suppl 1):44–53.

The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018,38(1):178.

Jääskeläinen SK. Pathophysiology of primary burning mouth syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol. 2012;123(1):71–7.

Kohorst JJ, Bruce AJ, Torgerson RR, Schenck LA, Davis MD. The prevalence of burning mouth syndrome: a population-based study. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(6):1654–6.

Bergdahl M, Bergdahl J. Burning mouth syndrome: prevalence and associated factors. J Oral Pathol Med. 1999;28(8):350–4.

Savage NW. Burning mouth syndrome: patient management. Aust Dent J. 1996;41(6):363–6.

Takenoshita M, Sato T, Kato Y, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses in patients with burning mouth syndrome and atypical odontalgia referred from psychiatric to dental facilities. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2010;6:699–705.

Tu TTH, Miura A, Shinohara Y, Mikuzuki L, Kawasaki K, Sugawara S, Suga T, Watanabe T, Watanabe M, Umezaki Y, Yoshikawa T, Motomura H, Takenoshita M, Toyofuku A. Evaluating burning mouth syndrome as a comorbidity of atypical Odontalgia: the impact on pain experiences. Pain Pract. 2017;18(5):580–6.

Abetz LM, Savage NW. Burning mouth syndrome and psychological disorders. Aust Dent J. 2009;54(2):84–93.

de Souza FT, Teixeira AL, Amaral TM, dos Santos TP, Abreu MH, Silva TA, Kummer A. Psychiatric disorders in burning mouth syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2012;72(2):142–6.

Bushnell MC, Ceko M, Low LA. Cognitive and emotional control of pain and its disruption in chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(7):502–11.

Leimola-Virtanen R, et al. Expression of estrogen receptor (ER) in oral mucosa and salivary glands. Maturitas. 2000;36:131–7.

Grushka M, et al. Taste dysfunction in burning mouth syndrome. Gerodontics. 1988;4:256–8.

Jääskeläinen SK. Clinical neurophysiology and quantitative sensory testing in the investigation of orofacial pain and sensory function. J Orofac Pain. 2004;18(2):85–107.

Neblett R, Cohen H, Choi Y, Hartzell MM, Williams M, Mayer TG, Gatchel RJ. The central sensitization inventory (CSI): establishing clinically significant values for identifying central sensitivity syndromes in an outpatient chronic pain sample. J Pain. 2013;14(5):438–45.

Woolf CJ. What is this thing called pain? J Clin Invest. 2010;120(11):3742–4.

Jääskeläinen SK. Is burning mouth syndrome a neuropathic pain condition? Pain. 2018;159(3):610–3.

Honda M, Iida T, Kamiyama H, Masuda M, Kawara M, Svensson P, Komiyama O. Mechanical sensitivity and psychological factors in patients with burning mouth syndrome. Clin Oral Investig. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-018-2488-9.

Umezaki Y, Miura A, Shinohara Y, Mikuzuki L, Sugawara S, Kawasaki K, Toyofuku A. Clinical characteristics and course of oral somatic delusions: a retrospective chart review of 606 cases in 5 years. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:2057–65.

Umezaki Y, Miura A, Watanabe M, Takenoshita M, Uezato A, Torihara A, Nishikawa T, Toyofuku A. Oral cenesthopathy. Biopsychosoc Med. 2016;10:20.

Khan SA, Keaser ML, Meiller TF, Seminowicz DA. Altered structure and function in the hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex in patients with burning mouth syndrome. Pain. 2014;155(8):1472–80.

Shinozaki T, Imamura Y, Kohashi R, Dezawa K, Nakaya Y, Sato Y, Watanabe K, Morimoto Y, Shizukuishi T, Abe O, Haji T, Tabei K, Taira M. Spatial and temporal brain responses to noxious heat thermal stimuli in burning mouth syndrome. J Dent Res. 2016;95(10):1138–46.

Yoshino A, Okamoto Y, Doi M, Okada G, Takamura M, Ichikawa N, Yamawaki S. Functional alterations of postcentral gyrus modulated by angry facial expressions during intraoral tactile stimuli in patients with burning mouth syndrome: a functional magnetic resonance imaging Study. Front Psychiatry. 2017;6(8):224.

Wada A, Shizukuishi T, Kikuta J, Yamada H, Watanabe Y, Imamura Y, Shinozaki T, Dezawa K, Haradome H, Abe O. Altered structural connectivity of pain-related brain network in burning mouth syndrome-investigation by graph analysis of probabilistic tractography. Neuroradiology. 2017;59(5):525–32.

Katagiri A, Sato Y, Umezaki Y, Sato T, Watanabe M, Takenoshita M, Yoshikawa T, Toyofuku A. Burning mouth Syndrome in an aged patient with Alzheimer's Disease : A case report. Jpn J Psychosom Dent. 2011;26(1):36–40 (article in Japanese).

Feller L, Fourie J, Bouckaert M, Khammissa RAG, Ballyram R, Lemmer J. Burning mouth syndrome: Aetiopathogenesis and principles of management. Pain Res Manag. 2017:1926269.

Tait RC, Ferguson M, Herndon CM. Chronic orofacial pain: burning mouth syndrome and other neuropathic disorders. J Pain Manag Med 2017;3(1). pii:120.

Mignogna MD, Fedele S, Lo Russo L, Leuci S, Lo Muzio L. The diagnosis of burning mouth syndrome represents a challenge for clinicians. J Orofac Pain. 2005;19(2):168–73.

Häggman-Henrikson B, Alstergren P, Davidson T, Högestätt ED, Östlund P, Tranaeus S, Vitols S, List T. Pharmacological treatment of oro-facial pain - health technology assessment including a systematic review with network meta- analysis. J Oral Rehabil. 2017;44(10):800–26.

Fischoff D, Spivakovsky S. Are pharmacological treatments for oro-facial pain effective? Evid Based Dent. 2018 Mar 23;19(1):28–9.

Zakrzewska J, Buchanan JA. Burning mouth syndrome. BMJ Clin Evid. 2016;2016:1301.

McMillan R, Forssell H, Buchanan JA, Glenny AM, Weldon JC, Zakrzewska JM. Interventions for treating burning mouth syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11:CD002779.

Fischoff DK, Spivakovsky S. Little evidence to support or refute interventions for the management of burning mouth syndrome. Evid Based Dent. 2017;18(2):57–8.

Richards D. Too many reviews too few trials. Evid Based Dent. 2018;19(1):2.

Toye F. Not everything that can be counted counts and not everything that counts can be counted' (attributed to Albert Einstein). Br J Pain. 2015;9(1):7.

Geisser ME, Kratz AL. How condition-specific do measures of pain intensity need to be? Pain. 2018;159(6):1001–2.

Finniss DG, Kaptchuk TJ, Miller F, Benedetti F. Biological, clinical, and ethical advances of placebo effects. Lancet. 2010;375(9715):686–95.

Peciña M, Bohnert AS, Sikora M, Avery ET, Langenecker SA, Mickey BJ, Zubieta JK. Association between placebo-activated neural systems and antidepressant responses: neurochemistry of placebo effects in major depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(11):1087–94.

de Souza IF, Mármora BC, Rados PV, Visioli F. Treatment modalities for burning mouth syndrome: a systematic review. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22(5):1893–905.

Toyofuku A. From psychosomatic dentistry to brain dentistry. Kokubyo Gakkai Zasshi 2007;74(3):161–168. (Article in Japanese).

Fenelon M, Quinque E, Arrive E, Catros S, Fricain JC. Pain-relieving effects of clonazepam and amitriptyline in burning mouth syndrome: a retrospective study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;46(11):1505–11.

Kawasaki K, Nagamine T, Watanabe T, Suga T, Tu TTH, Sugawara S, Mikuzuki L, Miura A, Shinohara Y, Yoshikawa T, Takenoshita M, Toyofuku A. An increase in salivary flow with amitriptyline may indicate treatment resistance in burning mouth syndrome. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2018;25:e12315.

Takeshi Watanabe, Kaoru Kawasaki, Trang T.H Tu, Takayuki Suga, Shiori Sugawara, Lou Mikuzuki, Anna Miura, Yukiko Shinohara, Tatsuya Yoshikawa, Miho Takenoshita, Akira Toyofuku, Takahiko Nagamine, The QTc shortening with amitriptyline may indicate treatment resistance in chronic nonorganic orofacial pain. Clinical Neuropsychopharmacology and Therapeutics, Released April 10, 2018, Online ISSN 1884–8826, Print ISSN.

Toyofuku A. Efficacy of milnacipran for glossodynia patients. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2003;7(Suppl 1):23–4.

Kato Y, Sato T, Katagiri A, Umezaki Y, Takenoshita M, Yoshikawa T, Sato Y, Toyofuku A. Milnacipran dose-effect study in patients with burning mouth syndrome. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2011;34(4):166–9.

Mitsikostas DD, Ljubisavljevic S, Deligianni CI. Refractory burning mouth syndrome: clinical and paraclinical evaluation, comorbiities. treatment and outcome J Headache Pain. 2017;18(1):40.

Nagamine T. Responsibility of the doctor who prescribes serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors for patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;72(1):45–6.

Riediger C, Schuster T, Barlinn K, Maier S, Weitz J, Siepmann T. Adverse effects of antidepressants for chronic pain: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Front Neurol. 2017;8:307.

Drossman DA, Tack J, Ford AC, Szigethy E, Törnblom H, Van Oudenhove L. Neuromodulators for functional gastrointestinal disorders (disorders of gut−brain interaction): a Rome Foundation working team report. Gastroenterology 2018;154:1140–1171.

Takenoshita M, Motomura H, Toyofuku A. Low-dose aripiprazole augmentation in amitriptyline-resistant burning mouth syndrome: results from two cases. Pain Med. 2017;18(4):814–5.

Umezaki Y, Takenoshita M, Toyofuku A. Low-dose aripiprazole for refractory burning mouth syndrome. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:1229–31.

Jimenez XF, Sundararajan T, Covington EC. A systematic review of atypical antipsychotics in chronic pain management: olanzapine demonstrates potential in central sensitization, fibromyalgia, and headache/migraine. Clin J Pain. 2018;34(6):585–91.

Heckmann SM, Kirchner E, Grushka M, Wichmann MG. Hummel T. A double-blind study on clonazepam in patients with burning mouth syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(4):813–6.

Kuten-Shorrer M, Treister NS, Stock S, Kelley JM, Ji YD, Woo SB, Lerman MA, Palmason S, Sonis ST, Villa A. Topical clonazepam solution for the Management of Burning Mouth Syndrome: a retrospective Study. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2017;31(3):257–63.

Goodman CW, Brett AS. Gabapentin and Pregabalin for pain - is increased prescribing a cause for concern? N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):411–4.

Bergdahl J, Anneroth G, Perris H. Cognitive therapy in the treatment of patients with resistant burning mouth syndrome: a controlled study. J Oral Pathol Med. 1995;24(5):213–5.

Femiano F, Gombos F, Scully C. Burning mouth syndrome: open trial of psychotherapy alone, medication with alpha-lipoic acid (thioctic acid). and combination therapy Med Oral. 2004;9(1):8–13.

Komiyama O, Nishimura H, Makiyama Y, et al. Group cognitive-behavioral intervention for patients with burning mouth syndrome. J Oral Sci. 2013;55(1):17–22.

Wergeland GJ, Fjermestad KW, Marin CE, et al. An effectiveness study of individual vs. group cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in youth. Behav Res Ther. 2014;57:1–12.

Matsuoka H, Himachi M, Furukawa H, et al. Cognitive profile of patients with burning mouth syndrome in the Japanese population. Odontology. 2010;98(2):160–4.

Matsuoka H, Chiba I, Sakano Y, Toyofuku A, Abiko Y. Cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosomatic problems in dental settings. Biopsychosoc Med. 2017;13(11):18.

Brailo V, Firić M, Vučićević Boras V, Andabak Rogulj A, Krstevski I, Alajbeg I. Impact of reassurance on pain perception in patients with primary burning mouth syndrome. Oral Dis. 2016;22(6):512–6.

Lopez-Jornet P, Lucero-Berdugo M, Castillo-Felipe C, Zamora Lavella C, Ferrandez-Pujante A, Pons-Fuster A. Assessment of self-reported sleep disturbance and psychological status in patients with burning mouth syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(7):1285–90.

Cheatle MD, Foster S, Pinkett A, Lesneski M, Qu D, Dhingra L. Assessing and managing sleep disturbance in patients with chronic pain. Sleep Med Clin. 2016;11(4):531–41.

Lami MJ, Martínez MP, Miró E, et al. Efficacy of combined cognitive- behavioral therapy for insomnia and pain in patients with fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Cogn Ther Res. 2018;42(1):63–79.

Bulloch AG, Patten SB. Non-adherence with psychotropic medications in the general population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45(1):47–56.

Yamazaki Y, Hata H, Kitamori S, Onodera M, Kitagawa Y. An open-label, noncomparative, dose escalation pilot study of the effect of paroxetine in treatment of burning mouth syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107(1):e6–11.

Palacio A, Garay D, Langer B, Taylor J, Wood BA, Tamariz L. Motivational interviewing improves medication adherence: a systematic review and Meta- analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(8):929–40.

Umezaki Y, Badran BW, DeVries WH, Moss J, Gonzales T, George MS. The efficacy of daily prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for burning mouth syndrome (BMS): a randomized controlled single-blind Study. Brain Stimul. 2016;9(2):234–42.

Umezaki Y, Badran BW, Gonzales TS, George MS. Daily left prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for medication-resistant burning mouth syndrome. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44(8):1048–51.

Suda S, Takagai S, Inoshima-Takahashi K, Sugihara G, Mori N, Takei N. Electroconvulsive therapy for burning mouth syndrome. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118(6):503–4.

McGirr A, Davis L, Vila-Rodriguez F. Idiopathic burning mouth syndrome: a common treatment-refractory somatoform condition responsive to ECT. Psychiatry Res. 2014;216(1):158–9.

Li BY, Tang HD, Qiao Y, Chen SD. Mental training for cognitive improvement in elderly people: what have we learned from clinical and neurophysiologic studies? Curr Alzheimer Res. 2015;12(6):543–52.

LeBlanc A, Herrin J, Williams MD, Inselman JW, Branda ME, Shah ND, Heim EM, Dick SR, Linzer M, Boehm DH, Dall-Winther KM, Matthews MR, Yost KJ, Shepel KK, Montori VM. Shared decision making for antidepressants in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1761–70.

Van Damme S, Becker S, Van Der Linden D. Tired of pain? Toward a better understanding of fatigue in chronic pain. Pain. 2018;159:7–10.

Solberg LI, Crain AL, Rubenstein L, Unützer J, Whitebird RR, Beck A. How much shared decision making occurs in usual primary care of depression? J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27(2):199–208.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported in part by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (grant number 16 K11881).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TTHT, MH, YA, HM, AT had major roles in drafting and revising the manuscript. TS, YA, TW contributed to the interpretation of ideas, reviewing the structure, and additional supplements. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tu, T.T.H., Takenoshita, M., Matsuoka, H. et al. Current management strategies for the pain of elderly patients with burning mouth syndrome: a critical review. BioPsychoSocial Med 13, 1 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13030-019-0142-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13030-019-0142-7