Abstract

Background

Postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock (PCCS) refractory to inotropic support and intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) occurs rarely but is almost universally fatal without mechanical circulatory support. In this systematic review and meta-analysis we looked at the evidence behind the use of veno-arterial extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation (VA ECMO) in refractory PCCS from a patient survival rate and determinants of outcome viewpoint.

Methods

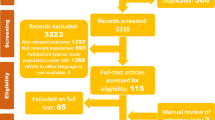

A systematic review was performed in January 2017 using PubMed (with no defined time period) using the keywords “postcardiotomy”, “cardiogenic shock”, “extracorporeal membrane oxygenation” and “cardiac surgery”. We excluded papers pertaining to ECMO following paediatric cardiac surgery, medical causes of cardiogenic shock, as well as case reports, review articles, expert opinions, and letters to the editor. Once the studies were collated, a meta-analysis was performed on the proportion of survivors in those papers that met the inclusion criteria. Meta-regression was performed for the most commonly reported adverse prognostic indicators (API).

Results

We identified 24 studies and a cumulative pool of 1926 patients from 1992 to 2016. We tabulated the demographic data, including the strengths and weaknesses for each of the studies, outcomes of VA ECMO for refractory PCCS, complications, and APIs. All the studies were retrospective cohort studies. Meta-analysis of the moderately heterogeneous data (95% CI 0.29 to 0.34, p < 0.01, I 2 = 60%) revealed overall survival rate to hospital discharge of 30.8%. Some of the commonly reported APIs were advanced age (>70 years, 95% CI −0.057 to 0.001, P = 0.058), and long ECMO support (95% CI −0.068 to 0.166, P = 0.412). Postoperative renal failure, high EuroSCORE (>20%), diabetes mellitus, obesity, rising lactate whilst on ECMO, gastrointestinal complications had also been reported.

Conclusion

Haemodynamic support with VA ECMO provides a survival benefit with reasonable intermediate and long-term outcomes. Many studies had reported advanced age, renal failure and prolonged VA ECMO support as the most likely APIs for VA ECMO in PCCS. EuroSCORE can be utilized to anticipate the need for prophylactic perioperative VA ECMO in the high-risk category. APIs can be used to aid decision-making regarding both the institution and weaning of ECMO for refractory PCCS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock (PCCS) refractory to inotropic support and intra-aortic balloon counter pulsation (IABP) is an infrequent but almost universally fatal condition without mechanical circulatory support (MCS) [1,2,3,4,5]. Veno-Arterial (VA) extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has been utilized as a salvage MCS after cardiac surgery for almost 50 years [6, 7]. The decisions surrounding when best to institute or withdraw such invasive and resource-intensive therapy remains controversial and there are no universally agreed upon guidelines on the indications for this therapy. VA ECMO in the context of refractory PCCS is mainly instituted as a temporizing measure as a “bridge to recovery” [5, 8, 9]. However, it has also been utilized as a “bridge to decision” and “destination therapy” with long-term implantable devices (e.g. left ventricular assist device, LVAD), and more rarely in the UK, “bridge to orthotopic heart transplantation (OHT)” [8,9,10]. Nevertheless, ECMO carries with it a significant morbidity rate, often associated with prolonged hospital stays and poor quality of life for the survivors after hospital discharge [5, 11].

In this systematic review and meta-analysis we have looked at the survival rate following VA ECMO for intractable PCCS in adults and some of the most commonly and consistently reported adverse prognostic indicators (API) in this group of patients.

Methods

A comprehensive literature search was performed in January 2017 using OVID/MEDLINE (PubMed) for all articles published in the English language in peer-reviewed journals. The inclusion criterion was post-cardiotomy VA ECMO in adults. We excluded all articles pertaining to VA ECMO for paediatric cardiac surgery as well as non-surgical indications for the use of this therapeutic modality e.g. myocarditis or cardiomyopathy. We also excluded case reports, review articles, expert opinions, and letters to the editor.

The search was performed, with no limit to the year of publication, using the following three search strategies:

Search 1: “(((Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) AND thoracic surgery) AND cardiac surgical procedures) AND shock, cardiogenic”,

Search 2: “((Extracorporeal membrane[Title]) OR ECMO[Title]) AND cardiac surgery[Title/Abstract]”.

Search 3: “ (((Extracorporeal membrane[Title]) OR ECMO[Title]) AND postcardiotomy[Title/Abstract])”.

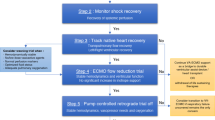

The first search strategy yielded 179 articles, the second search strategy yielded 149 articles and the third search strategy yielded 103 articles. The authors assessed the abstracts in all three searches. The “preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses” (“PRISMA”) guideline [12] was followed. When it was not possible to ascertain article suitability from its abstract alone we obtained the full text article for further assessment.

As this was a systematic review, ethical board review was not required. The primary outcome measure was determining the survival benefit following the institution of VA ECMO for refractory PCCS. The secondary outcome measure was identifying the most commonly reported APIs. The demographic data, APIs that had reached statistical significance (P < 0.05) in each study and crude data on outcome and follow-up, where available, were collated from each study. We then performed meta-regression to assess whether the APIs identified were significantly associated with survival.

Results

We identified 24 retrospective cohort studies that met the inclusion criteria from 1992 to 2016 in the English language literature. These studies as well as their strengths and weaknesses, are summarized in Table 1. In this review a cumulative total of 1926 patients required VA ECMO for PCCS.

Survival and follow-up

In the largest cohort with the longest follow up available in the literature, Rastan et al. reported results from 516 patients undergoing salvage ECMO for PCCS over a 12-year period from 1996 to 2008. They reported a survival to hospital discharge rate of 24.8% and a 13.7% 5-year survival [5]. In another large study Doll et al. reported results from 219 patients that underwent VA ECMO for PCCS from 1997 to 2002. They reported a 39% survival to hospital discharge and 17% 5-year survival [13].

In a multinational European study, Santarpino et al. collated data from 11 European cardiac surgical centers with cumulative results from 85 adult patients. Survival rate to hospital discharge was reported as 40% with a 1-year survival rate of 29.3% [14].

Li et al. reported on 123 adult patients who were salvaged with VA ECMO for refractory PCCS. They noted that 56% of patients were successfully weaned from VA ECMO and 34.1% survived to hospital discharge [15]. Elsharkawy et al. reported results from 233 patients with survival to hospital discharge was reported at 36% [16]. In another cohort study Wu et al. reported outcomes from 110 patients of whom 61% were successfully weaned and 42% were successfully discharged home [17].

Bakhtiary et al. reported a 55% survival to ECMO decannulation in their 45 patient cohort study, with a total in-hospital mortality rate of 71% for the cohort. In 3 years, 77% of the survivors were still alive [18]. Ko et al., analyzed the outcomes of 76 patients who underwent ECMO for intractable PCCS. Although 60.5% of patients survived to ECMO decannulation, 26.5% survived to hospital discharge. On 32+/−22 months follow-up, all survivors were of NYHA I-II functional status [19]. In a smaller cohort conducted by some of the authors of this systematic review, 35% survival to hospital discharge was observed and all survivors were still alive at 12 months with NYHA class I-II [20].

Complications

Major haemorrhage was the most commonly reported complication after institution of VA ECMO. It led to re-intervention in almost half of the patients in a few good quality studies [3, 5, 13, 14, 19, 20]. Factors such as the insult of the original operation, heparin infusion and heparin coated circuits are known to be the primary causes of bleeding [13]. Renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy (RRT) was the next most commonly reported complication [3, 5, 13, 20,21,22]. Stroke and sepsis also followed amongst the commonly encountered complications (see Table 1). Distal limb ischaemia is one of the most dreaded complications because if often leads to major morbidity. The largest study in this systematic review reported that almost 20% of patients with peripheral VA ECMO developed a degree of distal limb ischaemia. However, the use of a polyethylene terephthalate tube graft (e.g. DacronR) as a sewn side arm to the femoral or axillary arteries or the distal leg perfusion cannula reduced distal limb ischaemia and fasciotomy for compartment syndrome rate by almost 40% [5].

Adverse prognostic indicators

APIs that reached statistical significance and were directly associated with mortality in each study are summarized in Table 1. Advanced age (typically >70 years), although perhaps not in isolation [5, 15, 17, 21, 23], was the most commonly reported API. Development of renal failure, whilst on VA ECMO that required RRT had a strong association with mortality [5, 16, 23,24,25]. While this common complication in the context of VA ECMO for refractory PCCS is usually multifactorial. It is imperative to determine the most likely underlying aetiology/ies for renal dysfunction as early as possible. The following potential aetiologies should be identified and corrected as early as possible postoperatively: renal hypoperfusion due to poor forward flows whilst on VA ECMO, acute tubular necrosis due to prolonged hypotension preceding institution of support or syndrome of inappropriate anti-diuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) [26]. It is worth noting that the use of loop diuretics to address fluid overload or poor urine output leads to worsening renal dysfunction [26]. Rising serum lactate whilst on VA ECMO [5, 15, 21] has also been reported as a strong predictor of mortality. One study [5] advocated use of sodium bicarbonate infusion at an early stage to reduce metabolic acidosis and the organ damage that might ensue. Diabetes mellitus [5, 23], obesity [5, 23], gastrointestinal complications whilst on ECMO, high EuroSCORE (>20) and protracted ECMO support (>48 h) were also amongst the commonly reported APIs [17, 21, 26, 27]. It must however be acknowledged that prolonged ECMO support might reflect the complexity of the original operation and the patient’s poor clinical.

Although EuroSCORE was widely reported in the studies, it was quoted in its three versions (i.e. the additive EuroSCORE, logistic EuroSCORE and EuroSCORE II) over nearly 3 decades covered by this systematic review. This variation made meta-analysis for EuroSCORE as an API not possible.

Meta-analysis of survival to hospital discharge

We found that of the pooled total of 1926 patients, 594 (30.8%) survived to hospital discharge. We performed a meta-analysis on the outcome of interest i.e. the proportion of survivors. The software R was used with the package “metaprop”**. Meta-analysis is conducted to estimate the true unknown success rate of a procedure, by combining the results of several studies. Table 2 summaries the variables included in the meta-analyses. Figure 1 shows the forest plot describing each of the study’s proportion of survivors with their 95% confidence interval (CI).

Demonstrates the forest plot of the studies and the variables included in Table 2, describing each studies proportion of survivors (CI 95%)

Heterogeneity is present as defined by a statistically significant I 2 = 60%, which represents the percentage of variability in the effect estimates due heterogeneity rather than random error. A value of I 2 between 30 and 60% is considered as a moderate heterogeneity. By looking at the forest plot, one can observe that study 11 is well out from the rest. By removing study 11, the I 2 value dropped to 59%. The overall proportion of survivors is 31% (95% CI 0.29 to 0.34, p < 0.01, I 2 = 60%), but when considering random effect it raises to 33%.

Meta-regression of the adverse prognostic indicators

Meta-regression on the effects of moderators such as age, usage of pre-VA ECMO IABP support and duration of VA ECMO support was performed as these were the most commonly and consistently reported variables by most of the studies. Analysis showed that heterogeneity had been observed due to random sampling and variation in the methods used for the studies (Table 3). In order to account for at least part of the heterogeneity, mixed effects models are used by including moderators. This was also carried out using the package “metafor” in R software. By including the moderators the heterogeneity statistic I 2, which represents presence of variation in an inter-study effect size (proportion of survivors) dropped to 52.2% from the model without moderators (previously 60% see forest plot, Fig. 1), which is classified as moderate. We found that none of the coefficients of the moderators are statistically significant (Table 3), which means that there is no moderating effect of the mean age, usage of pre-VA ECMO IABP and the mean number of days on ECMO on the effect size. One of the reasons of the lack of power for the test on the coefficients is the small sample sizes used in the studies.

Furthermore, we looked at the possibility of publication bias in the meta-analysis. Our analysis showed no departure from symmetry in the funnel plot (Fig. 2), hence absence of bias. This claim is supported by the Egger’s test (p = 0.556).

Discussion

Our systematic review is the first of its kind to be published, analyzing the efficacy of VA ECMO as a salvage modality for refractory PCCS.

Refractory PCCS typically transpires at the end of a complex and prolonged operation [28]. It can also occur in an otherwise routine operation [5, 29] that has encountered an unexpected technical difficulty e.g. an iatrogenic injury to a vital structure during the course of an operation. In either case the patient cannot be weaned from cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) with survivable haemodynamic and arterial blood gas parameters, despite multiple inotropic support agents and IABP [30]. Furthermore, adding to the predicament, such cases typically encroach into “out-of-hours” [31] when the operating theatre team is fatigued and there is a relative lack of availability of technical assistance and experienced advice.

Why VA ECMO?

VA ECMO for refractory PCCS is typically established centrally i.e. arterial line through the ascending aorta and the venous line through the right atrium as part of the continuum with CPB at the end of the operation [5, 29]. Although in principal the conduct of CPB and VA ECMO are similar, there are several important advantages in using VA ECMO in the context of refractory PCCS [32]. The CPB achieves full VA bypass at lower flow rates (2–2.4 L/min/m2) with haematocrit levels of around 20%, leading to lower than physiological systemic oxygen delivery (DO2) [32]. A large dose (300–400 Units/kg) of unfractionated heparin (UH) is required to run CPB, as it is an “open circuit” with a venous reservoir (stagnant blood). In addition, full VA bypass is said to cause stasis of blood in the cardiac chambers and the pulmonary circulation warranting higher activated clotting times (ACT). VA ECMO on the other hand is more physiological. It uses partial VA bypass through a “closed circuit” (without a venous reservoir) and shorter tubing, typically in normothermia, with normal haematocrit levels, aiming for near normal DO2. As VA ECMO allows venous return to the heart, it allows cardiac ejection and less risk of thrombosis, thereby requiring minimal doses of UH as compared to CPB. This in-turn leads to fewer rates of postoperative bleeding complications requiring re-exploration whilst on MCS. VA ECMO is more versatile and is more easily manageable in the intensive care unit (ICU) setting for often-prolonged periods of time (i.e. days-weeks), unlike CPB, which is geared more towards short-term support (i.e. a few hours) [32]. The VA ECMO line tubing can be tunneled through the skin to allow chest closure. This maybe significant in that “incomplete sternal closure” has been reported as an independent predictor of mortality, as identified in a study by Unosawa et al. [27]. However, line change over to other sites, with axillary arterial, femoral arterial and femoral venous cannulation sites have previously been reported [5, 13]. Occasionally combined right atrial and femoral venous cannulation have been used to improve venous drainage [5]. Vascular access can be established with either surgical cut down or by Seldinger techniques. Some sew a side arm tube graft to the artery or use a distal perfusion cannula to reduce the risk of distal limb ischaemia and compartment syndrome (see complications) [5, 13].

Although ECMO is a valuable salvage modality, it is expensive [33]. It is very resource intensive due to its high demand on the ICU staff. It requires skilled staff performing high frequency monitoring for its safe application and maintenance [33]. These factors can pose a significant burden particularly on small and intermediate sized cardiac surgical centers, where the work force and bed capacity are both limited [30]. ECMO patients, on average, require more prolonged ICU stay than elective cases thereby leading to increased cancellation of elective and sometimes urgent cardiac surgical operations. As such, indiscriminant use of VA ECMO can result in major disturbance to an already stretched service [30].

Some centers in the UK rely on transplant centers for advice regarding whether or not to place PCCS patients on VA ECMO. If these patients are commenced on ECMO, they are transferred over to the larger transplant centers for further management [30, 34]. Critics had argued that, if only transplant units are funded to provide ECMO for PCCS support, similar patients at non-transplant cardiac surgical centers are denied of a life saving therapy [35]. In reality the use of VA ECMO for PCCS is not formally commissioned by the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK and the cost of treatment has to be absorbed by individual hospitals.

Kashani et al. [36], published an abstract on a systematic review covering only 11 case series with a cumulative pool of 1328 patients whereas our review covers 24 studies with a cumulative pool of 1926 patients. The survival rate to hospital discharge reported by Kashani et al. of 31.48% was comparable to our report of 30.8%. In their systematic review, they found similar APIs to our systematic review such as advanced age, elevated serum lactate after initiation of ECMO and renal failure [36]. Our meta-regression of APIs such as mean age, pre-VA ECMO use of IABP, effect of renal failure and mean ECMO duration however showed no statistically significant correlation between these parameters and survival, mainly due to the small sample sizes and presence of wide heterogeneity amongst study populations (Table 3).

This topic remains a controversial one with ethical and financial considerations for any cardiac surgical service. The decision as to whether or not to institute VA ECMO in the setting of PCCS remains difficult. Institution of VA ECMO for PCCS is usually not planned and the aetiology of the patient’s lack of progress may not be immediately apparent [19]. A study of 100 trans-catheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) patients, reported that anticipation for ECMO and institution of this mode of support prophylactically in the “high-risk” category on the EuroSCORE scale would potentially prevent the need for salvage VA ECMO, in a less optimal and controlled clinical setting, and carry better outcomes. In this study all-cause mortality occurred in none of the high-risk patients undergoing prophylactic VA ECMO (although p > 0.05) [37].

The literature demonstrates overwhelming evidence pointing towards reasonable survival rate to hospital discharge for patients undergoing ECMO for an otherwise universally fatal clinical condition. Furthermore reasonable intermediate-term and long-term survival rates as well as good quality of life have been reported in a few studies (Table 1) mainly for the survivors that do not manifest the APIs (see results). Major life threatening ECMO complications are common. We advocate a multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach to decision making for institution of ECMO in the context of refractory PCCS [29]. We recommend that given the ethical and cost implications, the surgeon, the anaesthetist, the on-call intensivist, the on-call perfusionist and a cardiac surgeon not involved in the operation (e.g. the on-call cardiac surgeon) should be involved in the decision making in whether or not to institute ECMO for refractory PCCS on a case-by-case basis [20]. We believe that due to the complexity of such cases protocols may not be an adequate substitute for an MDT approach to decision-making and management of such complex patients [5, 20]. Finally, in order to both preserve the patients’ autonomy and aid decision-making in the event of encountering refractory PCCS, we advocate that the possibility of the need for VA ECMO along with its pros and cons should be discussed with high-risk patients preoperatively and informed consent should be obtained in this regard.

Conclusions

We believe that VA ECMO provides a survival benefit for a significant proportion of patients with refractory PCCS, which is invariably a fatal clinical state. For hospital survivors, a reasonable intermediate and long-term functional outcome can be expected albeit at the expense of prolonged and often ridden hospital stay. We identified advanced age, renal failure and prolonged VA ECMO support to be commonly reported APIs. This claim however could not be supported by meta-regression due to small patient numbers and heterogeneity of the patient populations. Risk stratification tools such as the EuroSCORE can be utilized to anticipate the need for prophylactic perioperative VA ECMO in the high-risk category. The reported APIs should be taken into consideration before institution of and ongoing treatment with this laborious, invasive and expensive therapeutic modality.

Limitations

Most of the evidence available in the literature, including our analysis, pertains to older studies from the 1990s. Due to the nature of PCCS, randomization would not be appropriate and the studies typically constitute heterogeneous patient populations leading to skewing of the data. As for the pre-VA ECMO IABP application subgroup analysis, a few studies had not reported this data. In such studies we assumed that, in principal, all patients would have had IABP pre-VA ECMO institution. Hence the outcome of data analysis errs on the side of IABP usage. Small number of studies and heterogeneity of the patient populations meant that the statistical tests were not strong enough to detect statistical significance in our study. The data on EuroSCORE, rising lactate whilst on ECMO and the rate of obesity was not reported by enough studies to constitute a more objective analysis, hence deriving any solid conclusions regarding these indicators was difficult.

Abbreviations

- ACT:

-

Activated clotting time

- API:

-

Adverse prognostic indicator

- AS:

-

Aortic stenosis

- AVR:

-

Aortic valve replacement

- BiVAD:

-

Biventricular assist device

- CABG:

-

Coronary artery bypass grafting

- CHD:

-

Congenital heart disease

- CI:

-

Cardiac index

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- CPB:

-

Cardiopulmonary bypass

- CVA:

-

Cerebrovascular accident

- ECMO:

-

Extra-corporeal membrane oxygenator

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal

- IABP:

-

Intra-aortic balloon pump

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- LMS:

-

Left main stem coronary artery

- LV:

-

Left ventricular

- LVAD:

-

Left ventricular assist device

- MCS:

-

Mechanical circulatory support

- MDT:

-

Multidisciplinary team

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- MODS:

-

Multi-organ dysfunction syndrome

- MV:

-

Mitral valve

- MVR:

-

Mitral valve replacement

- MVR:

-

Mitral valve replacement

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

- NO:

-

Nitric oxide

- NYHA:

-

New York Heart Association

- OHT:

-

Orthotopic heart transplantation

- OHT:

-

Orthotopic heart transplantation

- PCCS:

-

Postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock

- PVD:

-

Peripheral vascular disease

- RV:

-

Right ventricular

- RVAD:

-

Right ventricular assist device

- SIADH:

-

Syndrome of inappropriate anti-diuretic hormone

- TAVI:

-

Trans-catheter aortic valve implantation

- TV:

-

Tricuspid valve

- TVR:

-

Tricuspid valve replacement

- UH:

-

Unfractionated heparin

- UK:

-

United Kingdom of Great Britain

- VA:

-

Veno-arterial

- VA:

-

Veno-arterial

References

Hernandez AF, Grab JD, Gammie JS, O’Brien SM, Hammill BG, Rogers JG, et al. A decade of short-term outcomes in post–cardiac surgery ventricular assist device implantation. Circulation. 2007;116:606–12.

DeRose JJ, Umana JP, Argenziano M, Catanese KA, Levin HR, Sun BC, et al. Improved results for Postcardiotomy Cardiogenic shock with the use of implantable left ventricular assist devices. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:1757–63.

Muehrcke DD, McCarthy PM, Stewart RW, Foster RC, Ogella DA, Borsh JA, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for Postcardiotomy Cardiogenic shock. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61:684–91.

Mohite PN, Sabashnikov A, Patil NP, Sáez DG, Zych B, Popov AF, et al. Short-term ventricular assist device in post-cardiotomy cardiogenic shock: factors influencing survival. J Artif Organs. 17(3):228–35.

Rastan AJ, Dege A, Mohr M, Doll N, Falk V, Walther T, et al. Early and late outcomes of 517 consecutive adult patients treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:302–11.

Fou AA, John H. Gibbon. The first 20 years of the heart-lung machine. Tex Heart Inst J. 1997;24(1):1–8.

Stewart GC, Giverts MM. Mechanical circulatory support for advanced heart failure: patients and technology in evolution. Circulation. 2012;125:1304–15.

Doll N, Fabricius A, Borger MA, Bucerius J, Doll S, Krämer K, et al. Temporary extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in patients with refractory postoperative cardiogenic shock--a single center experience. J Card Surg. 2003;18(6):512–8.

Hoy FB, Mueller DK, Geiss DM, Munns JR, Bond LM, Linett CE, et al. Bridge to recovery for postcardiotomy failure: is there still a role for centrifugal pumps? Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70(4):1259–63.

Rousse N, Juthier F, Pinçon C, Hysi I, Ban C, Robin E, et al. ECMO as a bridge to decision: recovery, VAD, or heart transplantation? Int J Cardiol. 2015;187:620–7.

Roussel A, Al-Attar N, Alkhoder S, Radu C, Raffoul R, Alshammari M, et al. Outcomes of percutaneous femoral cannulation for venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2012;1(2):111–4.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

Doll N, Kiaii B, Borger M, Bucerius J, Kramer K, Schmitt D, et al. Five year results of 219 consecutive patients treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation after refractory postoperative cardiogenic shock. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:151–7.

Santarpino G, Ruggieri VG, Mariscalco G, Bounader K, Beghi C, Fischlein T, et al. Outcome in patients having salvage coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116(8):1193–8.

Li CL, Wang H, Jia M, Ma N, Meng X, Hou XT. The early dynamic behavior of lactate is linked to mortality in postcardiotomy patients with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support: a retrospective observational study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;149(5):1445–50.

Elsharkawy HA, Li L, Esa WA, Sessler DI, Bashour CA. Outcome in patients who require venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2010;24(6):946–51.

Wu MY, Lin PJ, Lee MY, Tsai FC, Chu JJ, Chang YS, et al. Using extracorporeal life support to resuscitate adult postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock: treatment strategies and predictors of short-term and midterm survival. Resuscitation. 2010;81(9):1111–6.

Bakhtiary F, Keller H, Dogan S, Dzemali O, Oezaslan F, Meininger D, et al. Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for treatment of cardiogenic shock: clinical experiences in 45 adult patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135(2):382–8.

Ko WJ, Lin CY, Chen RJ, Wang SS, Lin FY, Chen YS, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support for adult Postcardiotomy Cardiogenic shock. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:538–45.

Khorsandi M, Dougherty S, Sinclair A, Buchan K, MacLennan F, Bouamra O, et al. A 20-year multicentre outcome analysis of salvage mechanical circulatory support for refractory cardiogenic shock after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;8(11):151.

Slottosch I, Liakopoulos O, Kuhn E, Deppe AC, Scherner M, Madershahian N, et al. Outcomes after peripheral extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy for postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock: a single-center experience. J Surg Res. 2013;181(2):47–55.

Mikus E, Tripodi A, Calvi S, Giglio D, Cavallucci A, Lamarra M, et al. CentriMag Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support as treatment for patients with refractory Postcardiotomy Cardiogenic shock. ASAIO J. 2013;59(1):18–23.

Smedira NG, Moazami N, Golding CM, McCarthy PM, Apperson-Hansen C, Blackstone EH, et al. Clinical experience with 202 adults receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for cardiac failure: survival at five years. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122:92–102.

Lin CY, Chen YC, Tsai FC, Tian YC, Jenq CC, Fang JT, et al. RIFLE classification is predictive of short-term prognosis in critically ill patients with acute renal failure supported by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:2867–73.

Kielstein JT, Heiden AM, Beutel G, Gottlieb J, Wiesner O, Hafer C, et al. Renal function and survival in 200 patients undergoing ECMO therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:86–90.

Pappalardo F, Montisci A. Veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA ECMO) in postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock: how much pump flow is enough? J Thorac Dis. 2016;8(10):1444–8.

Unosawa S, Sezai A, Hata M, Nakata K, Yoshitake I, Wakui S, et al. Long-term outcomes of patients undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock. Surg Today. 2013;43(3):264–70.

Acheampong B, Johnson JN, Stulak JM, Dearani JA, Kushwaha SS, Daly RC, et al. Postcardiotomy ECMO support after high-risk operations in adult congenital heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis. 2016;11(6):751–5.

Khorsandi M, Shaikhrezai K, Prasad S, Pessotto R, Walker W, Berg G, et al. Advanced mechanical circulatory support for post-cardiotomy cardiogenic shock: a 20-year outcome analysis in a non-transplant unit. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;11(29). doi:10.1186/s13019-016-0430-2.

Dunning J. Post-cardiotomy mechanical support update. SCTS annual meeting Belfast: Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain & Ireland; 2017.

Flécher E. AA, Corbineau H, Langanay T, Verhoye JP, Félix C, et al. current aspects of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in a tertiary referral centre: determinants of survival at follow-up. Eur J Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2014;46(4):665–71.

Annich GM, Lynch WR, MacLaren G, Wilson JM, Bartlett RH. Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonay support in critical care. 4th ed. ELSO: Michigan; 2012.

Emin A, Rogers CA, Parameshwar J, MacGowan G, Taylor R, Yonan N, et al. Trends in long-term mechanical circulatory support for advanced heart failure in the UK. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:1185–93.

Tsui S. Outcome of temporary MCS support for post- cardiotomy cardiogenic shock: is it worth the effort? In: meeting SA, editor. Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain & Ireland: Belfast; 2017.

Westaby S, Taggart D. Inappropriate restrictions on life saving technology. Heart. 2012;98(15):1117–9.

Kashani A, Manganas C. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in post-cardiotomy cardiogenic shock (PCCS) in adults: a systematic review. Heart Lung Circ. 2015;24(1):e56.

Seco M, Forrest P, Jackson SA, Martinez G, Andvik S, Bannon PG, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for very high-risk transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Heart Lung Circ. 2014;23(10):957–62.

Hsu PS, Chen JL, Hong GJ, Tsai YT, Lin CY, Lee CY, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory cardiogenic shock after cardiac surgery: predictors of early mortality and outcome from 51 adult patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;37:328–33.

Saeed D, Maxhera B, Westenfeld R, Lichtenberg A, Albert A, et al. An alternative approach for Perioperative extracorporeal life support implantation. Artif Organs. 2015;39(8):719–23.

Sajjad M, Osman A, Mohsen S, Alanazi M, Ugurlucan M, Canver C, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in adults: experience from the Middle East. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2012;2(5):521–7.

Pokersnik JA, Buda T, Bashour CA, Gonzalez-Stawinski GV. Have changes in ECMO technology impacted outcomes in adult patients developing postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock? J Card Surg. 2012;27(2):246–52.

Moreno I, Soria A, López Gómez A, Vicente R, Porta J, Vicente JL, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation after cardiac surgery in 12 patients with cardiogenic shock. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2011;58(3):156–60.

Wang SS, Chen YS, Ko WJ, Chu SH. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support for postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock. Artif Organs. 1996;20(12):1287–91.

Magovern GJ Jr, Magovern JA, Benckart DH, Lazzara RR, Sakert T, Maher TD Jr, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: preliminary results in patients with postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;57(6):1469–71.

Saxena P, Neal J, Joyce LD, Greason KL, Schaff HV, Guru P, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support in Postcardiotomy elderly patients: the Mayo Clinic experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;99(6):2053–60.

Yan X, Jia S, Meng X, Dong P, Jia M, Wan J, et al. Acute kidney injury in adult postcardiotomy patients with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: evaluation of the RIFLE classification and the acute kidney injury network criteria. European J Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2010;37(2):334–8.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None received.

Availability of data and materials

These can be obtained from the corresponding author (M. Khorsandi).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MK: primary investigator and first author, SD: manuscript drafting, OB: medical statistics, manuscript drafting, VP: manuscript drafting, PC: manuscript drafting, ST: manuscript drafting, SC: manuscript drafting, SW: manuscript drafting, NAA: manuscript drafting, VZ: Senior author, project supervisor, manuscript drafting. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable as this is a meta-analysis.

Consent for publication

Not applicable as this is a meta-analysis.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Khorsandi, M., Dougherty, S., Bouamra, O. et al. Extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory cardiogenic shock after adult cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Surg 12, 55 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-017-0618-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-017-0618-0