Abstract

Background

The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) is a determinants framework that may require adaptation or contextualization to fit the needs of implementation scientists in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). The purpose of this review is to characterize how the CFIR has been applied in LMIC contexts, to evaluate the utility of specific constructs to global implementation science research, and to identify opportunities to refine the CFIR to optimize utility in LMIC settings.

Methods

A systematic literature review was performed to evaluate the use of the CFIR in LMICs. Citation searches were conducted in Medline, CINAHL, PsycINFO, CINAHL, SCOPUS, and Web of Science. Data abstraction included study location, study design, phase of implementation, manner of implementation (ex., data analysis), domains and constructs used, and justifications for use, among other variables. A standardized questionnaire was sent to the corresponding authors of included studies to determine which CFIR domains and constructs authors found to be compatible with use in LMICs and to solicit feedback regarding ways in which CFIR performance could be improved for use in LMICs.

Results

Our database search yielded 504 articles, of which 34 met final inclusion criteria. The studies took place across 21 countries and focused on 18 different health topics. The studies primarily used qualitative study designs (68%). Over half (59%) of the studies applied the CFIR at study endline, primarily to guide data analysis or to contextualize study findings. Nineteen (59%) of the contacted authors participated in the survey. Authors unanimously identified culture and engaging as compatible with use in global implementation research. Only two constructs, patient needs and resources and individual stages of change were commonly identified as incompatible with use. Author feedback centered on team level influences on implementation, as well as systems characteristics, such as health system architecture. We propose a “Characteristics of Systems” domain and eleven novel constructs be added to the CFIR to increase its compatibility for use in LMICs.

Conclusions

These additions provide global implementation science practitioners opportunities to account for systems-level determinants operating independently of the implementing organization. Newly proposed constructs require further reliability and validity assessments.

Trial registration

PROSPERO, CRD42018095762

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Implementation scientists practicing in both low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and high income countries (HICs) increasingly use theories, models, and frameworks to optimize study design, data collection, analysis, and dissemination [1]. These guiding tools are intended to enhance the generalizability of findings by establishing common concepts and terminologies that can be applied across disparate research studies and settings. Due to its comprehensiveness and flexibility, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) is a popular framework that presents a taxonomy for conceptualizing and distinguishing between a wide spectrum of contextual determinants of implementation success, ranging from external implementation context to innate intervention characteristics [2]. Damschroder and colleagues introduced the CFIR in 2009 as a meta-theoretical framework compiling nineteen preceding implementation theories [2]. The CFIR presents five domains categorizing 39 constructs and provides a repository of standardized factors that influence implementation effectiveness [2]. The domains and constructs are intended to characterize the entirety of the implementation process (Appendix 1), and researchers are expected to select constructs that resonate with a particular research question. The CFIR is thus considered a “determinants framework” in that it can be applied with deductive reasoning to identify barriers and enablers that influence targeted implementation outcomes [1].

A 2016 systematic review identified 26 meaningful applications of the CFIR across a wide range of topic areas and acknowledged a number of opportunities to improve application of the CFIR across the research spectrum [3]. Notably, only two studies (8%) included in the systematic review took place in an LMIC (Kenya), with the remaining studies taking place in the USA, Canada, Sweden, the UK, and Australia. The CFIR, like most frameworks of implementation determinants, was conceived in an HIC [1, 4, 5]. However, implementation determinants might manifest differently in LMICs and HICs due to variations in health system structures, population-level morbidity and mortality profiles, resource availability, and cultural and socio-political norms. Implementation science theories, models, and frameworks, including the CFIR, may require adaptation or contextualization to fit the needs of implementation science practitioners in LMIC settings.

The purpose of this review is to report upon use of the CFIR in LMICs and provide recommendations on how the framework can be enhanced for optimal performance in implementation research in LMIC settings moving forward. Thus, three primary objectives of this review include the following: (1) to characterize the ways in which the CFIR has been applied in LMIC contexts, (2) to identify which CFIR constructs appear compatible, incompatible, or irrelevant with global implementation science research, and (3) to identify opportunities to refine the CFIR to optimize utility in LMIC settings.

Methods

The systematic review protocol is registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO #CRD42018095762) and followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Additional file 1) [6].

We searched Medline, CINAHL, PsycINFO, CINAHL, SCOPUS, and Web of Science from inception until April 5, 2019, to identify original peer-reviewed research in any language that cited the original CFIR publication by Damschroder and colleagues or mentioned CFIR in the title/abstract, and that took place within an LMIC. The classification of a country as an LMIC was determined based on the 2018 World Bank classification criteria [7]. The Covidence tool was used to remove duplicate studies and to conduct study screening [8]. Two reviewers (ARM and CK) reviewed all titles and abstracts independently, followed by independent full text review of remaining articles. Disagreements were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached.

During full text review, we excluded all studies that did not take place in an LMIC or were not published in peer-reviewed journals. We also excluded protocols, conference abstracts, editorials, and original research that cited the CFIR, but did not utilize the CFIR to guide study design, implementation, or analysis.

We abstracted data from each article using a standardized abstraction tool in Microsoft Excel to capture information relevant to: study location, study dates, health topic of focus, research objective, intervention, whether or not the intervention was part of a broader program or policy initiative, the target population, study design (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods), unit of analysis (patients/community members, providers at health facilities or in community-based programs, or organizations/health systems), phase of implementation (pre, during, or post-implementation), manner in which the CFIR was used (informing framework only, study design or formative evaluation, data collection, data analysis, interpret or contextualize findings, or multiple), CFIR domains and constructs of focus, rationale provided for selecting specific constructs, and any associations between key CFIR constructs and study outcomes (if investigated). These data abstraction categories purposively build off of and expand upon the review conducted by Kirk and colleagues to ensure comparability [3]. All articles were read in full and data were abstracted from studies by two reviewers (CK and MCGC), with a third reviewer independently reviewing and validating all data abstractions (ARM). Any discrepancies between reviewer interpretations or abstracted data were resolved via iterative group consultation until consensus was reached.

We designed a standardized questionnaire in REDCap, and sent the questionnaire to the corresponding author of most included studies (surveys were not sent to authors of studies published immediately prior to paper submission) [9]. Conference abstracts from the 2016, 2017, and 2018 AcademyHealth Annual Conferences on the Science of Dissemination and Implementation in Health were also reviewed to identify authors currently using the CFIR in LMICs whose publications were pending. The purpose of the questionnaire was to determine the following: (1) why the study authors chose the CFIR as a guiding framework for their research study, (2) which domains and constructs they found to be compatible, incompatible, or irrelevant to their research and why, and (3) ways in which the authors believe that the CFIR could be optimized or updated for use in LMIC contexts. Compatible constructs were those that were easily applied within the research study as the definition of the construct did not require any adaptation to fit the context in which the author was working. Incompatible constructs were not easily applied to the author’s research study, as the definition of the construct required significant adaption to fit the context in which they were working, or the specific topic of inquiry was not well described by the construct. Irrelevant constructs were those that were simply not pertinent to the research project at hand. Authors had the opportunity to provide further feedback about CFIR constructs and domains via open text boxes, and responses were reviewed to identify key patterns in newly proposed constructs or domains. Contacted authors were sent a reminder email if they did not initially respond to the online questionnaire within a 2-week period, with a final reminder sent 2 weeks later. If a corresponding author responded that a different study author should participate, instead that author was contacted as well.

Opportunities to optimize the CFIR were conceived through author insights in the published manuscripts, feedback from authors via the standardized questionnaires described above regarding specific recommendations for new constructs or domains, author feedback regarding challenges and theoretical gaps in the framework, as well as via the group discussion and consensus of the authors of this review.

Results

Systematic review

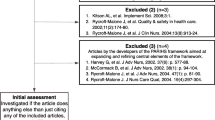

Our database search yielded 504 articles. Of those, 209 were duplicate articles and were removed, leaving 295 unique articles. The titles and abstracts of these articles were reviewed, and 149 articles were excluded because they did not take place in an LMIC or were a protocol or editorial. We conducted a full-text review of the 146 remaining articles, of which 112 full-text articles were excluded: 48 were removed due to citing but not utilizing the CFIR, 45 were not based in an LMIC, five were not peer reviewed, six were not primary research (e.g., systematic review), four were a study protocol, and four met several exclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

The final sample included 34 studies (Table 1). The studies were written by 31 different first authors. Publication dates ranged from 2011 to 2019. The articles addressed implementation questions in 25 LMICs and territories, including South Africa (n = 6), Kenya (n = 5), Mozambique (n = 5), Pakistan (n = 3), Tanzania (n = 3), Zambia (n =3), Bangladesh (n = 2), Cameroon (n = 2), China (n = 2), Morocco (n = 2), Rwanda (n = 2), Uganda (n = 2), Vietnam (n = 2), Benin (n = 1), Chad (n = 1), Chile (n = 1), Côte d’Ivoire (n = 1), Ghana (n = 1), India (n = 1), Malawi (n = 1), Mexico (n = 1), Nepal (n = 1), Nigeria (n = 1), Thailand (n = 1), and the US Associated Pacific Islands (n = 1). One study conducted research in Canada simultaneously with research in Kenya, and one study did not specify a country of focus [11], as it described analytical findings associated with a global surgery working group [37]. Seven (21%) of the included studies were conducted in more than one LMIC.

There were 18 different health topics of focus across the articles, including HIV (n = 8), maternal health (n = 5), primary healthcare (n = 3), pediatric inpatient care (n = 2), surgery (n = 2), tuberculosis (n = 2), chronic disease (n = 1), clinical practice guidelines (n = 1), general evidence-based health policies (n = 1), general evidence-based public health practice (n = 1), hepatitis C (n = 1), HPV vaccination (n = 1), immunizations (n = 1), integrated HIV and opioid treatment (n = 1), obesity (n = 1), pediatric mental health (n = 1), tobacco cessation (n = 1), and typhoid (n = 1).

Qualitative study designs were most common, and quantitative assessments were relatively rare. Twenty-three (68%) of the studies employed qualitative study designs, while 11 (32%) were mixed methods designs. Common qualitative methods utilized across the studies included focus group discussions and key informant interviews. Mixed methods studies used review of financial records [15], routine facility, or surveillance indicators [13, 17, 22, 28, 43], health worker questionnaires or other quantitative study process indicators [10, 20, 23, 28, 29], or validated surveys to calculate measures such as organizational readiness and provider burnout [24] in conjunction with qualitative research. CFIR constructs can be scored quantitatively and compared across cases according to strength and valence [44]. Quantitative scoring of constructs was employed in three studies [19, 24, 40]. Another study created a quantitative questionnaire to align with CFIR constructs, in which participants were asked to rate CFIR constructs on a 5-point Likert scale from “very unimportant” to “very important” for implementation success [10].

The unit of analysis for most of the articles was health providers in facilities or communities involved in implementation (n = 19), followed by organizations (e.g., health facilities, district health offices) involved in implementation (n = 12), patients benefiting from the intervention (n = 7), and policymakers and health system leaders at national or subnational levels (n = 5). Nine of the studies focused upon more than one unit of analysis [10, 13, 14, 16, 30, 35, 39, 40, 42].

The CFIR can address different research questions depending upon the stage of implementation in which it is used. For example, pre-implementation, Shi et al. applied the CFIR to guide data collection and identify potential barriers to evidence-based public health in the public sector [39]. Mid-implementation, Malham et al. used the CFIR to assess the extent to which a national action plan to strengthen the professional role of midwives was delivered as well as the barriers and facilitators influencing implementation [27]. And, post-implementation, Rwabukwisi et al. applied the CFIR to retrospectively evaluate a multi-country consortium of district-level health system strengthening interventions [36]. Over half of the articles in this review applied the CFIR post-implementation (n = 20), 26% during mid-implementation (n = 9) and 18% pre-implementation (n = 6). Sixteen of the articles applied the CFIR for more than one research purpose, most of which were to guide data analysis (n = 19) or contextualize study findings (n = 16). Other CFIR applications include guiding data collection (n = 14) and framing or designing the intervention (n = 4). Damschroder et al. suggest that when the CFIR is applied post-implementation, it should be used to link determinants of implementation to targeted outcomes (e.g., intervention acceptability or effectiveness) [2]. However, only 6 (18%) studies reporting linking outcomes to specific CFIR constructs, all of which took place mid- or post-implementation [10, 17, 19, 21, 24, 40]. These papers identified relationships between specific CFIR constructs and measures of high and low fidelity to the intervention [19], measures of high and low uptake of the intervention [21, 24, 40], successful implementation generally [10], as well as variations in implementation success, including successes in intervention management, supervision, and facilitation [17].

Discussion about the use of the CFIR constructs varied widely across the studies. Eight studies (24%) only reported the domains used without their corresponding constructs. Four studies (12%) reported neither the domains nor the constructs used, and 17 (50%) studies utilized at least one construct from all five domains. One study reported constructs linked to study outcomes, but did not specify which constructs were initially considered within the analysis. Complexity and networks and communication were the mostly commonly used constructs, while trialability was the least commonly used construct (Fig. 2). Two (6%) of the studies reported examining all CFIR constructs [17, 24]. Two studies utilized constructs added to the CFIR within the process domain: key stakeholders and innovation participants. However, given that these constructs are not widely acknowledged as part of the CFIR, they are not included in the analysis for purposes of consistency [19, 40]. Damschroder et al. suggest that CFIR constructs be selected for use based on salience, level of application (ex., individual or health facility) and time point of application, and that researchers provide a rationale for why certain constructs were considered pertinent to the research question. Only 7 (21%) of the studies provided some justification for selecting the CFIR constructs used.

Author survey

Nineteen (59%) of the 32 contacted authors participated in the survey. Most constructs were deemed by the authors to be compatible with use in LMICs (Fig. 3). Participating authors unanimously identified two constructs, organizational culture (inner setting domain), and engaging (process domain), as compatible with use in global implementation research. Some constructs were identified as irrelevant, largely due to the nature of the research question being asked. Only two constructs, relative advantage and trialability, both of which are within the intervention characteristics domain, were identified as irrelevant for use by five or more participating authors. Only two constructs, patient needs and resources (outer setting domain) and individual stages of change (characteristics of individual domain), were identified as incompatible with use by five or more participating authors.

Authors were requested to provide qualitative feedback regarding why specific constructs were considered incompatible with use. Regarding the construct of patient needs and resources, author responses followed two general themes. First, many studies employed interventions that took place at system levels broader than the facility (ex., district or national levels). Authors of these studies report that individual patient needs are not a compatible measure for health systems interventions inherently targeting systems-level barriers to care. Second, several authors reported that decision-making in the health systems in which their studies took place is not patient centered, and thus the construct is difficult to apply. Several authors added that organizational cultural or language barriers regarding practice norms made this construct particularly difficult to apply in an LMIC setting.

Authors who identified the construct of individual stages of change as incompatible cited that the construct is difficult to apply in health systems where the concept of individuality within a health care team is not compatible with the organizational culture. Many LMIC health care systems are more hierarchical than those in HICs, and the individual readiness of the health provider is less relevant. Tensions around individuality versus collectivism also influenced author perceptions of other CFIR constructs in the characteristics of the individual domain, such as self-efficacy and individual identification with organization.

Authors participating in the standardized questionnaire were asked to identify (1) circumstances in which the CFIR is not relevant for use in implementation research in LMICs, (2) possible adaptations or improvements that could be made to the CFIR for global implementation research, and (3) domains or constructs that should be added to improve relevancy. Responses to all three questions converged around prevailing themes of sub-organizational group or team-level influences on intervention delivery, as well as systems characteristics including perceived sustainability and scalability of interventions within the system. When asked about circumstances in which the CFIR may not be relevant to implementation science in LMICs, authors responses included the following:

In some settings health policy decisions are made from top down, and recipient will not have much option nor alternatives. In such conditions, CFIR individual and process domains might reflect skewed and over optimistic results – Author #29

Contexts vary largely such as the health systems and not only internally but the social norms, culture of the people and the political environment/economy...Therefore, it might be good to consider the macro-level factors as well – Author #32

When authors were asked about possible adaptations or improvements that could be made to the CFIR, most responses reinforced messaging regarding capturing health system dynamics influencing implementation. Authors had specific suggestions about constructs or domains that could be added to the CFIR to increase relevancy in LMICs, such as adding constructs that captured the resource constraints so often present in LMICs, as well as team-centered constructs that could focus on collective efficacy. Several authors also noted the need to include a systems-based domain, which could explore concepts of sustainability and long-term penetration of implementation activities within multiple levels of the health system. Author responses included the following:

It will be good if the CFIR can communicate more on how it can be used or applied in larger scale of actions such as implementation of national policy and strategy, not only at an intervention level – Author #22

More systems-based domains and constructs could be added in response to national and global actions such as accountability, governance & politics (both national and international) and legal and regulatory process. These factors play an important role in influencing the implementation of national policy – Author #23

It would be excellent if it could be adapted for use in researching health systems. In addition, if rather than, individuals there could be a domain for teams…I believe adding the domain of collective efficacy to characteristics of individuals would be useful – Author #38

Modifications to CFIR for LMIC settings

In order to address these perceived gaps in the CFIR taxonomy, as well as the experiences of review authors, we propose an additional domain called “Characteristics of Systems” to be added to the CFIR to increase its compatibility for use in LMICs. This domain includes constructs for, and related to, the relationship between key systems characteristics and implementation. Because proposed systems constructs have relational properties, they will inherently interact with existing constructs across domains. For example, the relative advantage of implementing an intervention may differ based on the perceived continuity of resources supporting implementation. Alternatively, the perceived sustainability of an intervention may be influenced by the adaptability of the intervention and the degree to which it can be tailored to meet local needs iteratively over time. As depicted in Fig. 4, a modified figure depicting the relationship of this additional domain with existing domains, each organization within a health system may have its own inner and outer setting, yet the system characteristics may be more ubiquitous across them. The Characteristics of Systems domain influences both the outer and inner settings in terms of how organizational culture and policy develop and, likewise, the two setting domains cyclically influence how health systems evolve or devolve over time through the actions and interactions of organizations within the system. The Characteristics of Systems domain has a similar relationship with the Individuals Involved and the Process of Implementation domains, wherein implementation determinants at the health systems level influence how individuals can or cannot engage in the process of intervention delivery. Likewise, the experiences of these individuals and implementation processes can engender health systems reforms that result in new implementation or innovation prospects.

We propose that the Characteristics of Systems domain contains six new constructs including: external funding agent priorities, system architecture, resource source, resource continuity, and strategic policy alignment. We also propose that several additional constructs be added to existing domains. These constructs include perceived scalability and perceived sustainability in the Characteristics of the Intervention domain, team characteristics and collective efficacy within the Inner Setting domain to account for the hierarchical practice norms more commonly present in LMICs, and community characteristics in the Outer Setting domain. Additionally, we suggest that decision-making be added to the Process domain. New constructs are defined in Table 2 and discussed below. Surveyed authors also proposed new constructs related to perceived feasibility and workload capacity; however, it was determined that perceived feasibility is well captured by existing CFIR constructs (ex., complexity, adaptability, and cost) while workload capacity is well captured by the existing Inner Setting construct, compatibility.

Discussion

Our review identified 34 studies that utilized the CFIR in LMICs to address a variety of health topics ranging from specific diseases to introduction of evidence-based policies generally. This suggests rapid growth in the use of CFIR to support LMIC-based implementation research. Like the 2016 Kirk et al. review of CFIR articles predominantly from HIC settings, the studies in this review primarily utilized qualitative methods; however, several applied the CFIR with quantitative data as well, often to organize and condense programmatic monitoring in order to identify and understand implementation barriers or facilitators. Unlike the preceding review in which the unit of analysis was mainly the organization in which implementation occurred or the providers involved in implementation, studies included in this review most frequently took place at levels above the health facility, including district-level interventions, national-level policies, or even global advocacy efforts [3]. This reflects differences in the organization of healthcare delivery in many LMICs as compared to HICs; in these settings, services are frequently offered within government funded health facilities that are part of nationwide systems.

This review also found that the CFIR was applied at multiple stages of implementation. Before implementation begins, the CFIR can be used to investigate implementation barriers or facilitators prospectively, thereby informing program design as well as generating testable hypotheses that focus on specific constructs and their interrelationships. During implementation, the CFIR can be used to monitor implementation progress. And at the end of a study, the framework can be used to help explain success or failure in a post-implementation interpretive evaluation or determine degree of success in a summative evaluation. Constructs that may be most influential in the effective implementation of a specific intervention can be identified and linked to implementation or innovation outcomes of interest. During this phase, data can be analyzed using CFIR-guided codebooks and standard qualitative analysis methodologies, as well as through cross-case comparisons that facilitate rating of constructs to reflect the magnitude and valence of key CFIR constructs in influencing effective implementation [44]. In this review, we found that most studies applied the CFIR post-implementation in order to interpret and contextualize study findings. Very few studies, however, linked specific CFIR constructs to targeted study outcomes through purposeful data analysis or cross-case comparisons. A similar trend was observed in the Kirk et al. review where over half of studies in HICs applied the CFIR post-implementation. There continues to be room for more meaningful applications of the CFIR in guiding study design, monitoring implementation processes, data analysis, and outcome interpretation [3].

Over one-third of studies did not explicitly state what CFIR constructs were utilized. Of those that did report upon constructs, the two most commonly utilized constructs included complexity (Intervention Characteristics domain) and networks and communication (Inner Setting domain) while the least frequently utilized construct was trialability (Intervention Characteristics domain). However, it is important to note that construct usage frequency does not necessarily reflect constructs of highest utility, but rather constructs of greatest relevance to the research question at hand. Compared to the Kirk et al. review, the construct intervention source was used more frequently within LMICs (9 applications, 3% of total constructs used) as compared to within HICs (4 applications, 2% of total constructs used). Likewise trialability was used much less frequently in LMICs (2 applications, 0.7% of total constructs used) as opposed to in HICs (6 applications, 3% of total constructs used) [3]. These divergent patterns in construct use may reflect contextual differences between LMICs and HICs, and highlight the importance of evaluating and adapting implementation frameworks for use in LMIC settings.

Authors responding to standardized questionnaires reported that existing CFIR constructs are largely compatible for use in LMICs. Some constructs were identified as irrelevant or incompatible (patient needs and resources and individual stages of change) primarily for two reasons. Many constructs were simply not relevant to the specific research question at hand, while others were deemed incompatible with the organizational culture or structure of the health system. These responses reinforce efforts to adapt the CFIR to ensure that it is fit for purpose across settings. However, these responses also suggest an opportunity to review CFIR definitions to ensure that they are easily interpretable for individuals from a variety of disciplines. For example, although respondents stated that patient needs and resources was not a relevant construct for interventions targeting district or national levels, implementation at higher levels of the health system can still be patient-centered when patient needs and barriers, and facilitators to meet those needs are prioritized. The CFIR can be used to determine if failure to prioritize patient needs and resources, at any level and due to any reason, including socio-cultural norms, may influence implementation effectiveness.

Adapting the CFIR for specific uses or settings is not unprecedented. A 2014 report prepared for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) by RTI International adapted the CFIR for use in three complex systems interventions: process redesign for improved efficiency and reduced costs, patient-centered medical homes, and care transitions between hospital and ambulatory care settings [47,48,49]. Across the three adapted frameworks, the report proposed the addition of two domains: a Measures of Implementation domain and an Outcomes domain to capture the effectiveness of implementation. Additionally, this effort renamed and redefined existing domains and constructs and proposed several dozen constructs specific to the systems interventions of focus. Proposed constructs included radicalness (Intervention Characteristics domain), technological environment (Outer Setting domain), patient self-management infrastructure (Inner Setting domain), collective efficacy (Characteristics of Individuals/Teams domain), measurement capability and data availability (Process domain), reach (Measures of Implementation domain), and equitable (Outcomes domain). While our review did not indicate a need to incorporate implementation measures and outcomes within the framework itself, it did corroborate the report’s description of key missing framework elements, namely sustainability and a focus on teams in addition to individuals.

Within a health system, each organization (e.g., a health facility) has its own distinct inner setting and outer setting. For proximal organizations (e.g., health facilities operating within the same district), the outer settings may be similar to one another or, in fact, the same. This phenomenon is best demonstrated in LMICs where governance is decentralized to local distinct subregions (i.e,. states or counties). In such countries, organizational outer settings across wider geographies or at different levels of the health system may exhibit significant variation due to differing health policies or practice norms in each subregion. For research in which the unit of analysis is above the organization, it may be necessary to consider other meta-characteristics of the health system. We propose the addition of a Characteristics of Systems domain to the current CFIR, which may help to resolve ambiguity regarding implementation determinants outside of the organization as well as distinguish between inner and outer settings within a hierarchical health system context. The proposed domain is relational, influencing and influenced by outer and inner settings, the process of implementation, the type and willingness of people to participate, and the progression through which an intervention is necessarily adapted. The proposed domain includes five constructs, several of which build upon existing models and theories, including the following: systems architecture, external funding agent priorities, strategic policy alignment, resource continuity, and resource source. We have also suggested that several constructs be added to existing domains, with the intention that additions should be made parsimoniously. These constructs include perceived scalability (Characteristics of the Intervention), team characteristics (Inner Setting), collective efficacy (Inner Setting), community characteristics (Outer Setting), and decision-making (Process, sub-construct of Executing). These eleven constructs are summarized in Table 2 and the justification for adding these constructs is described in more detail in Appendix 2. The addition of these constructs is intended to augment the utility and comprehensiveness of the CFIR in LMICs.

Conclusion

The purpose of this paper was to review existing applications of the CFIR in LMICs and learn from the reflections and experiences of authors who have utilized the CFIR in these settings. Limitations to this study include risk of incomplete retrieval of data from studies, or misinterpretation of reported study methodology. Our findings confirm that the CFIR is a popular and highly useful framework for global implementation science practitioners as it allows identification of implementation facilitators and barriers across settings. Constructs identified as more or less useful by authors often align with unique attributes of LMICs compared with HICs, such as more hierarchical versus more individualistic societies. To address the feedback provided, we have identified opportunities to adapt the CFIR for use in LMICs. Rather than redefine existing constructs, we have elected to maintain existing CFIR construct definitions so that past and future CFIR-based research operate within a standardized taxonomy. A newly proposed Characteristic of the System domain and constructs would provide global implementation science practitioners opportunities to account for health systems-level facilitators and barriers independent of the implementing organization. Newly proposed constructs have not yet been tested to ensure reliability and validity, which should be the focus of future measure development efforts.

Availability of data and materials

Abstracted data collected and analyzed during this study and described in this systematic review will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Qualitative responses from contacted authors are not available, as some of the information provided may be considered identifiable.

References

Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Science. 2015;10(1):53.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50.

Kirk MA, Kelley C, Yankey N, Birken SA, Abadie B, Damschroder L. A systematic review of the use of the consolidated framework for implementation research. Implement Sci. 2015;11(1):72.

Lewis CC, Fischer S, Weiner BJ, Stanick C, Kim M, Martinez RG. Outcomes for implementation science: an enhanced systematic review of instruments using evidence-based rating criteria. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):155.

Chaudoir SR, Dugan AG, Barr CH. Measuring factors affecting implementation of health innovations: a systematic review of structural, organizational, provider, patient, and innovation level measures. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):22.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Bank W World Bank Country and Lending Groups 2018 Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

Buregyeya E, Naigino R, Mukose A, Makumbi F, Esiru G, Arinaitwe J, et al. Facilitators and barriers to uptake and adherence to lifelong antiretroviral therapy among HIV infected pregnant women in Uganda: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:1.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81.

Barac R, Als D, Radhakrishnan A, Gaffey MF, Bhutta ZA, Barwick M. Implementation of interventions for the control of typhoid fever in low- and middle-income countries. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;99(3_Suppl):79–88.

Bardosh KL, Murray M, Khaemba AM, Smillie K, Lester R. Operationalizing mHealth to improve patient care: a qualitative implementation science evaluation of the WelTel texting intervention in Canada and Kenya. Global Health. 2017;13:1–15.

Chu CE, Wu F, He X, Zhou K, Cheng Y, Cai W, et al., editors. Hepatitis C virus treatment access among human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus (HCV)-coinfected people who inject drugs in Guangzhou, China: implications for HCV treatment expansion. Open forum infectious diseases: Oxford University Press; 2016.

Cole C, Pacca J, Mehl A, Tomasulo A, van der Veken L, Viola A, et al. Toward communities as systems: a sequential mixed methods study to understand factors enabling implementation of a skilled birth attendance intervention in Nampula Province, Mozambique. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):132.

Cooke A, Saleem H, Hassan S, Mushi D, Mbwambo J, Lambdin B. Patient and provider perspectives on implementation barriers and facilitators of an integrated opioid treatment and HIV care intervention. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2019;14(1):3.

Dansereau E, Miangotar Y, Squires E, Mimche H, El Bcheraoui C. Challenges to implementing Gavi’s health system strengthening support in Chad and Cameroon: results from a mixed-methods evaluation. Global Health. 2017;13(1):83.

Dogar O, Elsey H, Khanal S, Siddiqi K. Challenges of integrating tobacco cessation interventions in TB programmes: case studies from Nepal and Pakistan. J Smoking Cessation. 2016;11(2):108–15.

English M, Nzinga J, Mbindyo P, Ayieko P, Irimu G, Mbaabu L. Explaining the effects of a multifaceted intervention to improve inpatient care in rural Kenyan hospitals-interpretation based on retrospective examination of data from participant observation, quantitative and qualitative studies. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):124.

English M. Designing a theory-informed, contextually appropriate intervention strategy to improve delivery of paediatric services in Kenyan hospitals. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):39.

Gimbel S, Rustagi AS, Robinson J, Kouyate S, Coutinho J, Nduati R, et al. Evaluation of a systems analysis and improvement approach to optimize prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV using the consolidated framework for implementation research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(Suppl 2):S108.

Gimbel S, Mwanza M, Nisingizwe MP, Michel C, Hirschhorn L. Improving data quality across 3 sub-Saharan African countries using the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR): results from the African health initiative. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(3):828.

Gutiérrez-Alba G, González-Block MÁ, Reyes-Morales H. Challenges in the implementation of clinical practice guidelines in major public health institutions in Mexico: a multiple case study. Salud Publica Mex. 2015;57(6):547–54.

Hosey GM, Rengiil A, Maddison R, Agapito AU, Lippwe K, Wally OD, et al. US associated Pacific islands health care teams chart a course for improved health systems: implementation and evaluation of a non-communicable disease collaborative model. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(4A):19.

Huang K-Y, Nakigudde J, Rhule D, Gumikiriza-Onoria J, Abura G, Kolawole B, et al. Transportability of an evidence-based early childhood intervention in a low-income African country: results of a cluster randomized controlled study. Prev Sci. 2017;18(8):964–75.

Jones DL, Rodriguez VJ, Butts SA, Arheart K, Zulu R, Chitalu N, et al. Increasing acceptability and uptake of voluntary male medical circumcision in Zambia: implementing and disseminating an evidence-based intervention. Transl Behav Med. 2018;8(6):907–16.

Landis-Lewis Z, Manjomo R, Gadabu OJ, Kam M, Simwaka BN, Zickmund SL, et al. Barriers to using eHealth data for clinical performance feedback in Malawi: a case study. Int J Med Inform. 2015;84(10):868–75.

Abou-Malham S, Hatem M, Leduc N. Analyzing barriers and facilitators to the implementation of an action plan to strengthen the midwifery professional role: a Moroccan case study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):1–15.

Malham SA, Hatem M, Leduc N. A case study evaluation of an intervention aiming to strengthen the midwifery professional role in Morocco: anticipated barriers to reaching outcomes. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2015;8:419.

McRobie E, Wringe A, Nakiyingi-Miiro J, Kiweewa F, Lutalo T, Nakigozi G, et al. HIV policy implementation in two health and demographic surveillance sites in Uganda: findings from a national policy review, health facility surveys and key informant interviews. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):47.

Myburgh H, Murphy JP, van Huyssteen M, Foster N, Grobbelaar CJ, Struthers HE, et al. Implementation of an electronic monitoring and evaluation system for the antiretroviral treatment programme in the Cape Winelands district, South Africa: a qualitative evaluation. PloS One. 2015;10(5):e0127223.

Naidoo N, Zuma N, Khosa NS, Marincowitz G, Railton J, Matlakala N, et al. Qualitative assessment of facilitators and barriers to HIV programme implementation by community health workers in Mopani district, South Africa. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0203081.

Nathavitharana RR, Daru P, Barrera AE, Mostofa Kamal S, Islam S, Sultana R, et al. FAST implementation in Bangladesh: high frequency of unsuspected tuberculosis justifies challenges of scale-up. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21(9):1020–5.

Naude CE, Zani B, Ongolo-Zogo P, Wiysonge CS, Dudley L, Kredo T, et al. Research evidence and policy: qualitative study in selected provinces in South Africa and Cameroon. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):126.

Petersen Williams P, Petersen Z, Sorsdahl K, Mathews C, Everett-Murphy K, Parry CD. Screening and brief interventions for alcohol and other drug use among pregnant women attending midwife obstetric units in Cape Town, South Africa: a qualitative study of the views of health care professionals. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2015;60(4):401–9.

Phulkerd S, Sacks G, Vandevijvere S, Worsley A, Lawrence M. Barriers and potential facilitators to the implementation of government policies on front-of-pack food labeling and restriction of unhealthy food advertising in Thailand. Food Policy. 2017;71:101–10.

Rodriguez VJ, LaCabe RP, Privette CK, Douglass KM, Peltzer K, Matseke G, et al. The Achilles’ heel of prevention to mother-to-child transmission of HIV: protocol implementation, uptake, and sustainability. SAHARA J. 2017;14(1):38–52.

Rwabukwisi FC, Bawah AA, Gimbel S, Phillips JF, Mutale W, Drobac P. Health system strengthening: a qualitative evaluation of implementation experience and lessons learned across five African countries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(3):826.

Saluja S, Silverstein A, Mukhopadhyay S, Lin Y, Raykar N, Keshavjee S, et al. Using the consolidated framework for implementation research to implement and evaluate national surgical planning. BMJ Global Health. 2017;2(2):e000269.

Sax S, Marx M. Local perceptions on factors influencing the introduction of international healthcare accreditation in Pakistan. Health Policy Plann. 2013;29(8):1021–30.

Shi J, Jiang C, Tan D, Yu D, Lu Y, Sun P, et al. Advancing implementation of evidence-based public health in China: an assessment of the current situation and suggestions for developing regions. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:1–8.

Soi C, Gimbel S, Chilundo B, Muchanga V, Matsinhe L, Sherr K. Human papillomavirus vaccine delivery in Mozambique: identification of implementation performance drivers using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):151.

VanDevanter N, Kumar P, Nam N, Linh N, Trang N, Stillman F, et al. Application of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to assess factors that may influence implementation of tobacco use treatment guidelines in the Viet Nam public health care delivery system. Implement Sci. 2017;12:1–8.

Warren CE, Ndwiga C, Sripad P, Medich M, Njeru A, Maranga A, et al. Sowing the seeds of transformative practice to actualize women’s rights to respectful maternity care: reflections from Kenya using the consolidated framework for implementation research. BMC Womens Health. 2017;17:1–18.

White MC, Randall K, Capo-Chichi NFE, Sodogas F, Quenum S, Wright K, et al. Implementation and evaluation of nationwide scale-up of the surgical safety checklist. Br J Surg. 2019;106(2):e91–e102.

Damschroder LJ, Lowery JC. Evaluation of a large-scale weight management program using the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR). Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):51.

Scheirer MA, Dearing JW. An agenda for research on the sustainability of public health programs. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(11):2059–67.

Lemieux-Charles L, McGuire WL. What do we know about health care team effectiveness? A review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(3):263–300.

Rojas Smith L, Ashok M, Morss Dy S, Wines R, Teixeira-Poit S. Contextual frameworks for research on the implementation of complex system interventions. Methods research report. (Prepared by the RTI International–University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Evidence-Based Practice Center under contract No. 290-2007-10056-I.). Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014.

Dy SM, Ashok M, Wines RC, Smith LR. A framework to guide implementation research for care transitions interventions. J Healthc Qual. 2015;37(1):41–54.

Ashok M, Hung D, Rojas-Smith L, Halpern MT, Harrison M. Framework for research on implementation of process redesigns. Qual Manag Health Care. 2018;27(1):17–23.

Ilott I, Gerrish K, Booth A, Field B. Testing the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research on health care innovations from South Yorkshire. J Eval Clin Pract. 2013;19(5):915–24.

Moore JE, Mascarenhas A, Bain J, Straus SE. Developing a comprehensive definition of sustainability. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):110.

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76.

Lennox L, Maher L, Reed J. Navigating the sustainability landscape: a systematic review of sustainability approaches in healthcare. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):27.

Proctor E, Luke D, Calhoun A, McMillen C, Brownson R, McCrary S, et al. Sustainability of evidence-based healthcare: research agenda, methodological advances, and infrastructure support. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):88.

Barker PM, Reid A, Schall MW. A framework for scaling up health interventions: lessons from large-scale improvement initiatives in Africa. Implement Sci. 2015;11(1):12.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the authors of all studies included in this systematic review who have contributed immensely to the growth of implementation science in low- and middle-income countries. We also extend our sincere thanks to Ms. Elspeth Nolen for supporting the design of the paper’s figures.

Previous presentation

A version of this paper was originally presented at the 11th Annual Conference on the Science of Dissemination and Implementation in Health, Washington, DC, December, 2018.

Funding

No additional funding was provided to support this systematic review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ARM, JW, BJW, KS, SG, CGK, and BHW conceived the design of the study. CK and ARM led the review of abstracts, titles, and full texts, with support from MCGC for data abstraction. ARM led the drafting of the manuscript, with all authors contributing to review, feedback, and collective decision-making regarding key results and CFIR adaptation recommendations. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This systematic review was conducted using published data, and study authors were contacted for additional contextual information. This study was considered non-research by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board (IRB) self-determination process.

Consent for publication

The current research does not include details, images, or videos relating to an individual person; thus, the need for written informed consent for the publication of such details is not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

PRISMA Checklist.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Description of newly proposed constructs

Implementation science foci include adoption or selection of evidence-based interventions, implementation of interventions using carefully selected implementation strategies, and scale-up of the interventions. Each focus, but particularly the third, requires consideration of unique, local health systems and national, regional, and global policies that influence broad delivery of evidence-based practices. However, as currently designed, the CFIR process domain ends at reflecting and evaluating, without conceptual next steps for expanding implementation. Author questionnaire respondents, in addition to CFIR utilizers from HICs, identified spread and scale as key missing constructs [50]. Thus, two newly proposed constructs include perceived sustainability (Characteristics of the Intervention) and perceived scalability (Characteristics of the Intervention). The construct of perceived sustainability is intended to capture the perceived likelihood of continued use of program components and activities for the continued achievement of desirable program and population outcomes [45]. Sustainability is a key implementation outcome, and definitions of sustainability vary in the implementation literature [51, 52]. This construct, as presented, is intended to capture perceptions of sustainability at a health systems level throughout and after implementation, and not sustained behavior at an individual level. For studies focused solely on studying determinants or outcomes of sustainability, we suggest that researchers utilize models and frameworks focused explicitly on exploring the dynamics of sustainability [53, 54].

The CFIR can currently be applied to anticipate implementation needs through exploration of constructs such as planning, executing, and reflecting and evaluating. However, the newly proposed construct scalability is intended to capture the perceived potential of implementation expansion so that that the innovation/intervention is available across wider geographic or practice settings. This construct would be appropriate for use to capture perceptions regarding why an intervention could or could not scale, and how implementation could be modified or optimized to enhance replicability of core intervention components. The construct reflects issues and opportunities related to health system infrastructure and capacity, and are thus inherently linked to constructs within all CFIR domains. However, if researchers aim to study scale-up as an outcome, as opposed to a determinant, more comprehensive scalability frameworks are recommended [55]. It is our hope that by adding constructs of both perceived sustainability and perceived scalability to the CFIR, these important features of implementation will be more frequently and more fully explored as determinants of implementation by global implementation researchers.

Several other constructs were proposed within the new Characteristics of Systems domain. The systems architecture construct addresses how the many organizations operating within a health system, each with their own inner and outer settings, interact with one another to influence implementation. The systems architecture construct thus inherently builds upon structural characteristics in the Inner Setting. This construct may be particularly useful for multi-level interventions targeting different implementation mechanisms and administrative levels of a health system and could be used to stratify and apply constructs across levels. Systems architecture may also be particularly useful when conducting cross-country analyses, as the design of a health system, including the degree of decentralization, often influences which implementation strategies are most effective in a given setting. Two resource-specific constructs are also included within the domain, including resource source and resource continuity, both of which reflect unique determinants of implementation outcomes in LMICs. Together, they highlight the flow of resources outside of the organization, and the economic and strategic trends that influence where and how these resources are made available to the organization. They also complement available resources, a construct found in the Inner Setting domain, which describes the level of resources available to an organization for implementation.

Linking the Characteristics of Systems, Outer Setting, and Intervention domains is the construct of external funding agent priorities, which highlights how funding agents influence both intervention design and the implementation environment. This construct complements but is distinct from external policies and incentives within the Outer Setting domain as external funding agent priorities can often influence how interventions are derived, designed, prioritized and delivered, thus permeating multiple existing CFIR domains. The construct of strategic policy alignment was added in response to requests for constructs that capture how the priorities of various stakeholders and organizations do or do not reflect local governmental health policies. This construct also expands upon external policies and incentives by identifying how a specific policy or guideline is introduced or delivered within the health system and can be used to highlight policies or guidelines that are in conflict with one another or do not align with long-term health planning documents.

In response to author feedback and influenced by the Integrated Team Effectiveness Model (ITEM), we also propose a construct for team characteristics in the Inner Setting domain to capture how interpersonal norms and dynamics influence implementation within an organization [46]. Team characteristics are distinct from the existing construct of learning climate, which is focused primarily on skill development and growth. Rather, team characteristics can capture and describe interpersonal norms that influence implementation within hierarchical health systems, including concepts such as team accountability, workflow, and allocation of responsibilities. Team characteristics are also related to the newly proposed construct of collective efficacy, a team’s shared belief in their capability to execute activities and achieve their common implementation goals.

This research also highlighted the need to account for community characteristics as a new construct in the Outer Setting domain because communities, community mobilization, and community infrastructure are the foundation of an effective, decentralized public health system. This construct recognizes the effect that communities can have on individual patients, health providers, and organizations by influencing patient care seeking as well as intervention design, delivery processes, and supportive policies. Notably, this construct would also apply in circumstances in which community stigma or resistance might influence design or uptake of an intervention.

Finally, the construct decision-making is proposed within the Process domain as a sub-construct of the existing construct, executing. While executing reflects implementation fidelity, timeliness, and engagement, decision-making distinctly emphasizes the many actions that must be taken in the process of making timely and effective decisions about implementation. Decision-making is highly linked to reflecting and evaluating within the Process domain, in that decisions will be made in light of or despite of implementation benchmarks, and likewise implementation monitoring is often designed to inform relevant decisions. Notably, this construct was also proposed within the AHRQ-RTI CFIR adaptation [47].

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Means, A.R., Kemp, C.G., Gwayi-Chore, MC. et al. Evaluating and optimizing the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) for use in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Implementation Sci 15, 17 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-0977-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-0977-0