Abstract

Background

Diversified etiology of lower respiratory tract infection renders diagnosis challenging. The mainstay microbial culture is time-consuming and constrained by variable growth requirements. In this study, we explored the use of Nanopore sequencing as a supplementary tool to alleviate this diagnostic bottleneck.

Methods

We developed a targeted Nanopore method based on amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA gene and fungal internal transcribed spacer region. The performance was compared with routine infectious disease workups on 43 respiratory specimens.

Results

Nanopore successfully identified majority of microbes (47/54, 87.04%) and 7 possible pathogens not detected by routine workups, which were attributable to the content of microbiological investigations (n = 5) and negative culture (n = 2). The average sequencing time for first target reads was 7 min (1–43 min) plus 5 h of pre-sequencing preparation.

Conclusions

The Nanopore method described here was rapid, economical and hypothesis-free, which might provide valuable hints to further microbiological follow-up for opportunistic pathogens missed or not detectable by conventional tests.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI) are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide [1]. As guided by clinical and epidemiological factors, microbiological investigations may be carried out to determine the etiology, especially for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) with moderate and high severity [2, 3]. Nevertheless, CAP pathogens are diversified which render etiologic diagnosis challenging. The mainstay microbial culture is time-consuming and may only identify a pathogen up to 40% of cases due to variable growth requirements [4]. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays have been demonstrated useful for improving pathogen detection from lower respiratory specimens [5, 6], yet the targets are confined to key bacteria which may only represent the tip of an iceberg.

Recently, next-generation sequencing (NGS) facilitates a universal approach for pathogen detection, which may revolutionize infectious disease diagnostics [7]. In particular, Nanopore technology provides the speed that can shorten sample-to-answer time, which is important for the severely ill. From literature, several research groups explored the use of Nanopore sequencing for pneumonia diagnosis, utilizing both metagenomic and targeted approaches [8,9,10,11]. In this study, we adopted the targeted approach because it enables higher depth of microbial reads and thus allowing more room for multiplexing which significantly lowers the cost. We developed a targeted Nanopore method for simultaneous detection of bacterial and fungal pathogens, and compared its performance with routine infectious disease workups on archived respiratory specimens harboring diversified microbial species.

Methods

Specimens

The specimens were selected based on microbial diversity. The 43 respiratory specimens were collected between May 2016 and September 2019 in Department of Pathology, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital. These comprised 34 lower and 9 upper respiratory specimens, and the details are summarized in Table 1.

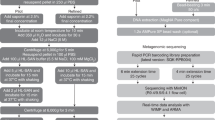

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) extraction and PCR

Standard laboratory practices were applied to minimize risk of infection and contamination. DNA extraction was performed using EMAG (bioMérieux, Marcy, I’Etoile, France) with blank lysis buffer as negative control. Bacterial 16S ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) gene and fungal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region were amplified using universal primers 27F-1492R/ 533F-1100R and ITS5-ITS4, respectively, with human beta-globin gene as PCR inhibition control. Primer sequences and PCR conditions are described in Tables 2 and 3.

Nanopore sequencing library preparation

Nanopore sequencing libraries were prepared using Ligation Sequencing Kit 1D (SQK-LSK109) (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, England) with or without PCR-free Native Barcoding Expansion Kit (EXP-NBD104/114) (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, England). The libraries were loaded and sequenced on MinION flow cells (FLO-MIN106D R9.4.1) (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, England) after quality control runs.

Data analysis

MinKNOW version 2.0 was used for live basecalling. FASTQ files were analyzed on Nanopore EPI2ME platform with default minimum qscore of 7. Bacterial and fungal identification were facilitated via 16S and ‘What’s in my Pot?’ (WIMP) workflows, respectively. Reads assigned to all target and possible pathogens were counter-checked with National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) basic local alignment search tool (BLAST), or re-analyzed by GAIA 2.0. For all possible pathogens, consensus sequences were built from BAM files using Unipro UGENE (version 1.29.0) and their similarity to reference genomes was determined. The elapsed sequencing time of first target reads was recorded. Relative abundance values of bacterial and fungal pathogens were calculated separately.

Confirmation of possible pathogens

Presence of possible pathogens was further confirmed by PCR-sequencing using genus- or species-specific primers (Table 4).

Results

The results are summarized in Table 1. The first target reads were detected with average sequencing time of 7 min (1–43 min), plus 5 h of pre-sequencing preparation. Nanopore successfully identified majority of the microbes (47/54, 87.04%), and the false negatives were primarily due to low microbial burden, as reflected by negative smear (Patient 11), scanty or no microbial growth from culture (Patient 11, 25 and 32), and late cycle threshold values of real-time PCR assays (Patient 38 and 40).

Interestingly, Nanopore identified 7 possible pathogens from 6 patients, which were not detected by routine workups. The consensus sequences of these possible pathogens showed 99–100% identity to reference sequences, and their presence was confirmed by PCR-sequencing except for Patient 18 due to sample insufficiency. The 7 possible pathogens included common causes of typical and atypical pneumonia (n = 2: Legionella pneumophila and Streptococcus pneumoniae), as well as opportunistic pathogens (n = 5: Candida albicans, Candida haemulonis, Corynebacterium striatum, Leptotrichia wadei and Rothia mucilaginosa). These findings might be attributable to 2 factors. First, the routine workups did not include tests for microbes concerned (n = 5). Taking Patient 12 as an example, results of sputum PCR and serum immunoglobulin G test suggested Chlamydia pneumoniae infection, yet 80 and 0.8% of 16S reads were mapped to S. pneumoniae and C. pneumoniae, respectively. The former was more abundant and might have been isolated by culture, however, bacterial culture was not included in the workup. Another factor was negative culture (n = 2). For instance, in the bronchoalveolar lavage of Patient 24, majority of 16S reads (64%) were mapped to L. wadei, which might prefer anaerobic growth conditions and therefore not isolated from standard culture [18].

Discussion

Our data revealed the heterogeneous nature of respiratory microbiome of the patients, which is hardly hinted by clinical signs and symptoms [19], but the content of microbiological investigation is often determined by this limited information. Considering the 6 patients with possible pathogens, half of the routine workups comprised 4–7 tests (average for all patients: 4). To a certain extent, the data revealed the bottleneck of etiologic diagnosis, that is, routine workups comprised a bundle of narrow-spectrum tests without targeting the culprit. Broad-spectrum, hypothesis-free NGS methods may contribute to improved etiologic diagnosis by supplementing the limitations of conventional tests and providing hints for further microbiological follow-up. A more complete picture on relative abundance of each microbial species may also help distinguish between causative agents and colonizers, especially in co-infection. Benefiting from the real-time sequencing by Nanopore technology, sample-to-answer time may be reduced to facilitate prompt pathogen-specific confirmatory work and treatment, which are essential for improved clinical outcome.

There are several diagnostic-grade molecular tests for pneumonia diagnosis, for example, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved BioFire FilmArray Pneumonia Panel and Explify Respiratory by ARUP Laboratories and IDbyDNA. The former identifies 33 targets from lower respiratory specimens in about 1 h, including 18 common LRTI bacteria with semi-quantitative results for 15 [20]. The latter works by metagenomic DNA and RNA sequencing (illumina NextSeq) enabling non-targeted detection of virtually any microbial targets within 48 h [21]. Our targeted Nanopore method is an intermediate between the two, in terms of speed (FilmArray > Nanopore > Explify) and detection spectrum (Explify > Nanopore > FilmArray). FilmArray appears to be a good option for first-line pathogen detection and Explify/ Nanopore may be a useful investigatory tool for culture- and FilmArray-negative opportunistic infections caused by rare pathogens. Considering the reagent cost, our Nanopore method is a competitive option among the 3. The per-sample reagent cost was about USD 68.87 for a 24-plex MinION run, and could be flexibly scaled for single sporadic cases on Flongle (USD 218.23) (Table 5). Nevertheless, as Nanopore technology is rapidly evolving, it is not easy to clinically validate a Nanopore-based assay at this moment due to requirements on ‘wet lab’ and bioinformatics analysis method standardization.

Our method had several limitations. First, the sensitivity for low-abundance microbial species was lower in a background of upper respiratory commensals. Second, we observed that 27F primer failed to detect C. pneumoniae for Patient 12, 20 and 28. In silico sequence evaluation revealed mismatches at 3′ end of 27F primer when aligned with C. pneumoniae reference sequence (nucleotide 8–20, NCBI Accession Number: NR_026527.1). The problem was resolved by including 533F-1100R primers for 16S analysis and this highlighted the importance of optimal primer choices for the best species coverage. We also observed that several species were misidentified by EPI2ME, for instance, Streptococcus mitis was misidentified as S. pneumoniae, and C. albicans was misidentified as Candida auris. Confirmation of results with alternative pipelines is therefore advisable. Like many DNA-based molecular assays, we could not determine cell viability from sequencing data. Close communication between physicians and laboratorians is therefore warranted to correlate laboratory data with clinical presentation. In addition, as this was purely a laboratory microbiology study, we had no clinical outcome data on treatment results to validate the etiology of each case.

Conclusion

Our data shed light on potential value of targeted Nanopore sequencing for supplementing the limitations of conventional diagnostic workflow. It may not have the best of its value for common non-viral causes of respiratory infection, as these can be readily resolved by microbial culture and multiplex PCR, yet it may contribute to improved etiological diagnosis of opportunistic infection caused by rare pathogens. Future prospective study with greater pathogen diversity and clinical outcome data is warranted to further assess assay performance and streamline the protocol. With continuously improving sequencing technology as well as user-friendly workflow and price, we envision that Nanopore-based methods will be closer to the doors of clinical laboratories in the near future.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BLAST:

-

Basic local alignment search tool

- CAP:

-

Community-acquired pneumonia

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- FDA:

-

Food and drug administration

- ITS:

-

Internal transcribed spacer

- LRTI:

-

Lower respiratory tract infection

- NCBI:

-

National center for biotechnology information

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- rRNA:

-

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid

- WIMP:

-

‘What’s in my Pot?’

References

GBD 2016 Lower Respiratory Infections Collaborators. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of lower respiratory infections in 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:1191–210.

Lim WS, Smith DL, Wise MP, Welham SA. British Thoracic Society. British Thoracic Society community acquired pneumonia guideline and the NICE pneumonia guideline: how they fit together Thorax. 2015;70:698–700.

Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, Anzueto A, Brozek J, Crothers K, et al. Diagnosis and treatments of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:e45–67.

Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, Fakhran S, Balk R, Bramley AM, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:415–27.

Gadsby NJ, Russell CD, McHugh MP, Mark H, Conway Morris A, Laurenson IF, et al. Comprehensive molecular testing for respiratory pathogens in community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:817–23.

Buchan B, Windham S, Faron M, Balada-Llasat J, Relich R, Humphries R, et al. Clinical evaluation and potential impact of a semi-quantitative multiplex molecular assay for the identification of pathogenic bacteria and viruses in lower respiratory specimens. In: Abstracts of American Thoracic Society 2018 International Conference; San Diego; 2018 May 18–23; Abstract A107: American Thoracic Society; 2018. https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2018.197.1_MeetingAbstracts.A2617.

Dulanto Chiang A, Dekker JP. From the pipeline to the bedside: advances and challenges in clinical metagenomics. J Infect Dis. 2019;pii:jiz151.

Moon J, Jang Y, Kim N, Park WB, Park KI, Lee ST, et al. Diagnosis of Haemophilus influenzae pneumonia by Nanopore 16S amplicon sequencing of sputum. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:1944–6.

Charalampous T, Kay GL, Richardson H, Aydin A, Baldan R, Jeanes C, et al. Nanopore metagenomics enables rapid clinical diagnosis of bacterial lower respiratory infection. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:783–92.

Irinyi L, Hu Y, Hoang MTV, Pasic L, Halliday C, Jayawardena M, et al. Long-read sequencing based clinical metagenomics for the detection and confirmation of Pneumocystis jirovecii directly from clinical specimens: a paradigm shift in mycological diagnostics. Med Mycol. 2019;pii:myz109.

Yang L, Haidar G, Zia H, Nettles R, Qin S, Wang X, et al. Metagenomic identification of severe pneumonia pathogens in mechanically-ventilated patients: a feasibility and clinical validity study. Respir Res. 2019;20:265.

Frank JA, Reich CI, Sharma S, Weisbaum JS, Wilson BA, Olsen GJ. Critical evaluation of two primers commonly used for amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:2461–70.

Walters W, Hyde ER, Berg-Lyons D, Ackermann G, Humphrey G, Parada A, et al. Improved bacterial 16S rRNA gene (V4 and V4–5) and fungal internal transcribed spacer marker gene primers for microbial community surveys. mSystems. 2015;1(pii):e00009–15.

Kembel SW, O’Connor TK, Arnold HK, Hubbell SP, Wright SJ, Green JL. Relationships between phyllosphere bacterial communities and plant functional traits in a neotropical forest. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:13715–20.

Ristaino JB, Madritch M, Trout CL, Parra G. PCR amplification of ribosomal DNA for species identification in the plant pathogen genus Phytophthora. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:948–54.

Marín M, Garcia-Lechuz JM, Alonso P, Villanueva M, Alcalá L, Gimeno M, et al. Role of universal 16S rRNA gene PCR and sequencing in diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:583–9.

Flahaut M, Sanglard D, Monod M, Bille J, Rossier M. Rapid detection of Candida albicans in clinical samples by DNA amplification of common regions from C. albicans-secreted aspartic proteinase genes. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:395–401.

Eribe ERK, Olsen I. Leptotrichia species in human infections II. J Oral Microbiol. 2017;9:1368848.

Metlay JP, Kapoor WN, Fine MJ. Does this patient have community-acquired pneumonia? Diagnosing pneumonia by history and physical examination. JAMA. 1997;278:1440–5.

The BioFire FilmArray Pneumonia (PN) Panel. (2020) https://www.biofiredx.com/products/the-filmarray-panels/filmarray-pneumonia. Accessed on 28 Mar 2020.

Detection of Previously Missed Pathogens in Immunocompromised Children with Suspected Pulmonary Infections by a Validated Next-Generation Sequencing Test (Explify Respiratory). (2017) http://www.idbydna.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Detection-of-Previously-Missed-Pathogens_ATS-2017.pdf. Accessed on 28 Mar 2020.

Acknowledgements

We thank the colleagues of Department of Pathology, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, for their dedicated and professional work on routine laboratory diagnosis.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BSFT and WSC conceived and designed the study. BSFT, ESKM, TLC, CHA, SML, DNH, EYLW, MYT, MKN and WSC were involved in data collection and analysis. WSC wrote the first draft. All authors critically reviewed and approved this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted with the approval of Research Ethics Committee (REC) of Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital. The reference number is RC-2019-29. The specimens used were left-over total nucleic acid after routine testing. All personal identifiers were removed in the whole research process. Consent to participate: not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, W.S., Au, C.H., Leung, S.M. et al. Potential utility of targeted Nanopore sequencing for improving etiologic diagnosis of bacterial and fungal respiratory infection. Diagn Pathol 15, 41 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-020-00960-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-020-00960-w