Abstract

Background

Nanotubular structures, denoted tunneling nanotubes (TNTs) have been described in recent times as involved in cell-to-cell communication between distant cells. Nevertheless, TNT-like, long filopodial processes had already been described in the last century as connecting facing, growing microvessels during the process of cerebral cortex vascularization and collateralization. Here we have investigated the possible presence and the cellular origin of TNTs during normal brain vascularization and also in highly vascularized brain tumors.

Methods

We searched for TNTs by high-resolution immunofluorescence confocal microscopy, applied to the analysis of 20-µm, thick sections from lightly fixed, unembedded samples of both developing cerebral cortex and human glioblastoma (GB), immunolabeled for endothelial, pericyte, and astrocyte markers, and vessel basal lamina molecules.

Results

The results revealed the existence of pericyte-derived TNTs, labeled by proteoglycan NG2/CSPG4 and CD146. In agreement with the described heterogeneity of these nanostructures, ultra-long (> 300 µm) and very thin (< 0.8 µm) TNTs were observed to bridge the gap between the wall of distant vessels, or were detected as short (< 300 µm) bridging cables connecting a vessel sprout with its facing vessel or two apposed vessel sprouts. The pericyte origin of TNTs ex vivo in fetal cortex and GB was confirmed by in vitro analysis of brain pericytes, which were able to form and remained connected by typical TNT structures.

Conclusions

None of the multiple roles described for TNTs can be excluded from a possible involvement during the processes of both normal and pathological vessel growth. A possible function, suggested by the pioneering studies made during cerebral cortex vascularization, is in cell searching and cell-to-cell recognition during the processes of vessel collateralization and vascular network formation. According to our results, it is definitely the pericyte-derived TNTs that seem to actively explore the surrounding microenvironment, searching for (site-to-site recognition), and connecting with (pericyte-to-pericyte and/or pericyte-to-endothelial cell communication), the targeted vessels. This idea implies that TNTs may have a primary role in the very early phases of both physiological and tumor angiogenesis in the brain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In 2004, Amin Rustom, Hans-Hermann Gerdes and Colleagues described in the journal Science [1], “highly sensitive nanotubular structures formed de novo between pheochromocytoma cultured cells, that create complex networks” as a sort of “highways” dedicated to cell-to-cell communication. Actually, it was at the very beginning of the century that Amin Rustom observed these long, delicate cell strands for the first time, owing to a mistake in culture protocol, and named them tunneling nanotubes (TNTs) (see Anil Ananthaswamy, https://www.sott.net/article/170469-Tunnelling-nanotubes-Lifes-secret-network and Viviane Callier, https://www.quantamagazine.org/cells-talk-and-help-one-another-via-tiny-tube-networks-20180423/). Although TNTs have been described in recent times, long pseudopodial processes were firstly described by Thomas Bär [2] as structures connecting facing, growing microvessels, “…filopodia may be responsible for the establishment of intervascular bridges which later become canalized” (part of Bär’s original diagram is shown in Additional file 1). Additional structural and functional characteristics of TNTs have subsequently been revealed by a number of studies (published from 2006 to 2008) carried out on different cell types in vitro [3,4,5,6]. TNTs were demonstrated to accomplish long-range, directed communication between dislodged cells and to mediate intercellular transfer of diverse molecules and cell components [3]. They were described as having an average length of 30 µm and in some case above 140 µm, and have been grouped into two main classes, very thin (≤ 0.7 µm, measuring a minimum of 100–200 nm) and thick (≥ 0.7 µm, up to 1 µm) [4]. TNTs heterogeneity does not only depend on their extension and diameter but is also due to differences in their own molecular features [5, 6] like, for instance, the inconstant presence of actin microfilaments, gap junctions and lipid raft-type membrane microdomains [1, 7,8,9]. Two main classes of TNTs have been described, according to their different morphology/function: TNTs type I, short dynamic structures, containing actin filament and engaged in exploring the surrounding microenvironment, and TNTs type II, that are longer and more stable processes, containing cytokeratin filaments and apparently involved in organelles shuttle [6].

The history of TNTs discovery testifies to their extreme fragility; in fact, they are very sensitive structures that can be damaged by light exposure, shearing force and chemical fixation [1], consistent traits that have hampered TNTs histological observation in ex vivo tissues. Hence the prevalence of in vitro studies that have investigated TNTs biological significance and molecular composition. The first evidence of the existence of TNTs in tissues, in vivo, was elegantly demonstrated and documented by Chinnery, Pearlman, and McMenamin in 2008, when they described TNTs in the corneal stroma of chimeric mouse, between donor-derived MHC class II+ cells and resident MHC class II+ cells [10]. More recently, TNT-like structures in vivo have been described in human pleural mesothelioma and adenocarcinoma [11], in cultured explants of ovarian cancer [12], and in solid samples of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma [13]. Our knowledge of TNT function has been improved by studies demonstrating the involvement of TNTs in Herpes viruses intercellular spread [14, 15], in myeloid cell communication in immune surveillance [16], and their use as ‘emergency highways’ for the transport of vital organelles during situations posing a risk of apoptosis in damaged cells [17]. In addition, TNT communication via chemical messengers and/or the transfer of organelles between malignant cells involved in cancer growth, invasion and metastasis has recently gained in importance, revealing TNTs as a promising target in cancer therapy [18, 19]. Obviously this concept can be extended to other diseases, such as neurodegenerative diseases, in which a TNT pathogenesis has been suggested [20, 21]. To date, only few publications describing the existence of TNTs in the central nervous system have been published and, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have investigated ‘vascular’ TNTs during physiological and tumor angiogenesis in the brain.

We firstly observed TNTs in the developing human telencephalon at 18 wg, during Bär’s second stage of intracortical vascularization, a phase featuring cerebral cortex vascular network formation and characterized by a rapid increase in vessel branching and vessel density [2, 22, 23]. At this time, TNTs were identified on slides immunostained with fibronectin (FN), one of the major molecular components of the vessel basal lamina (VBL). On these fields, TNTs were revealed as tiny structures, stretched between two microvessels, but were often interrupted and difficult to follow over their entire length (Fig. 1a, b). A more appropriate tissue processing, with lighter fixation and amplified immunostaining systems applied to thick, free-floating sections, as well as overexposed laser confocal microscope settings, improved the TNTs structural preservation and detection, allowing us to observe very long, tiny TNTs bridging facing microvessels (Fig. 1c, d). Additional examples of straight and spiraled, non-bridged FN+ TNTs are shown in Additional files (Additional file 2a–f).

Representative confocal microscopy images of TNTs in the developing human telencephalon at 18 wg. a, c Fibronectin (FN) staining reveals the basal lamina of cerebral cortex microvessels and FN+ TNTs (arrows). b, d On the single FN channel (green) the FN+ TNT in (b) appears interrupted (arrows), while in d a long and fine FN+ TNT (arrows) bridges the gap between two distant vessels. Nuclear counterstaining propidium iodide (PI). Scale bars a–d 25 µm

These observations opened out the vista of a possible involvement of TNTs in vessel growth and cell-to-cell communication during brain vascularization. Following up on this idea, we investigated the cellular ‘source(s)’ of TNTs in the microvessel wall by laser confocal immunofluorescence, using antibodies against specific cellular (endothelial cells, pericytes, and perivascular astroglia) and molecular (collagen type IV and VI) microvessel components. The analysis was carried out on cerebral cortex samples from human fetuses at midgestation (18 and 22 weeks of gestation, wg) and on human glioblastoma (GB) specimens, as an example of pathological angiogenesis in highly vascularized brain tumors. Based on these results in tissue ex vivo, culture assays were added to explore the formation of TNTs in vitro.

Tissue and culture results indicate pericytes as the main source of TNTs during the processes of vessel growth and branching in both developing brain and GB, suggesting that these cells are involved in neuroangiogenesis and in tumoral angiogenesis preventive recognition and communication steps, through their active, vascular TNT wiring.

Methods

Fetal specimen histology and immunostaining

Autopsy specimens of fetal brain were collected from fetuses at 18 and 22 weeks of gestation (wg; 2 for each of the examined ages) spontaneously aborted due to preterm rupture of the placental membranes and with no history of neurological pathologies. Permission to collect fetal tissue was obtained from the mother at the end of the abortion procedure. The sampling and handling of the specimens conformed to the ethical rules of the Department of Emergency and Organ Transplantation, Division of Pathology, University of Bari School of Medicine, and approval was gained from the local Ethics Committee of the National Health System in compliance with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. The fetal age was estimated based on the crown-rump length and/or pregnancy records (counting from the last menstrual period). At autopsy, the fetuses did not reveal macroscopic structural abnormalities and/or malformations of the central nervous system. The dorso-lateral wall of each telencephalic vesicle (future cerebral cortex), was dissected, along the coronal planes, in samples (n = 6) about 0.5 cm thick, fixed for 2–3 h at 4 °C by immersion in 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) plus 0.2% glutaraldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS, pH 7.6) and then washed in PBS. For each fetus, 3–4 samples were serially cut using a vibrating microtome (Leica Microsystem; Milton Keynes, UK) into 20-µm sections, parts of which were processed for conventional histological analysis with toluidine blue staining to ascertain the absence of microscopic malformations. All the other sections were stored at 4 °C in PBS plus 0.02% PFA for immunolabeling and fluorescence microscopy. Single and multiple immunostainings were carried out with the following polyclonal (pAb) and monoclonal (mAb) antibodies diluted in blocking buffer (BB; 1% bovine serum albumin and 2% fetal calf serum in PBS): pAb anti-fibronectin (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), mAb anti-CD31 (Dako), pAb anti-CD105 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), pAb anti-Glut-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), mAb anti-CD146 (Abcam), pAb anti NG2/CSPG4 D2 (gift from William B. Stallcup, The Burnham Institute for Medical Research, La Jolla, CA, USA), mAb anti-collagen type IV (Dako), pAb anti-collagen type IV (Acris Antibodies GmbH; Herford, Germany), pAb anti-collagen type VI (Abcam), and mAb anti-GFAP (Vision Biosystem Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) (Table 1). Free-floating sections were incubated with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min at room temperature (RT), BB 30 min at RT, followed by incubation, with single or combined primary antibodies, overnight at 4 °C and with appropriate fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (fluorophore 488, 555, and 633; Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA, USA) or biotinylated secondary antibodies for 45 min at RT, the latter subsequently revealed by fluorophore-conjugated streptavidin (Streptavidin-Alexa 488, Streptavidin-Alexa 555; Thermo Fisher Scientific) (Table 1). After each incubation step the sections were washed 3 times for 5 min with PBS. The sections were then post-fixed in 4% PFA for 10 min and nuclear counterstaining was performed by incubations either in RNase (diluted 5 µl/ml in PBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and then propidium iodide (PI; diluted 1 µl/ml in PBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific) or by TOPRO-3 or SYTOX (diluted 1:10 K in PBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Finally, the sections were allowed to adhere on polylysine slides (Menzel-Glaser, GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany) by drying for 10 min at RT, were coverslipped with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA), and sealed with nail varnish. Negative controls were prepared by omitting the primary antibodies and by mismatching the secondary antibodies.

Glioblastoma histology and immunostaining

Glioblastoma (GB) samples (n = 6) were collected from primary tumors specimens obtained in a previous study, in which the imaging techniques and histological analysis were specified in detail [24]. The six GB patients were males (n = 4) aged from 30 to 55 years-old, and females (n = 2), of 52 and 53 years-old, who underwent surgery at the Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital Zurich (Switzerland). Written informed consent was obtained from patients before study entry. All procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Bari Medical School and by the Ethics Committee of Canton Zurich, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Glioma samples were classified according to the WHO 2007 criteria. The samples were dissected (≤ 0.5 cm in thickness) and then fixed for 2–3 h at 4 °C by immersion in 2% PFA plus 0.2% glutaraldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS, pH 7.6). Specimens were then washed in PBS, and serially cut using a vibrating microtome (Leica Microsystem; Milton Keynes, UK); 20-μm sections were stored at 4 °C in PBS plus 0.02% PFA for immunolabeling and fluorescence microscopy. Double immunostainings were carried out with mAb anti-CD31 and pAb anti-collagen type IV, as described for fetal sections. Negative controls were prepared by omitting the primary antibodies and by mismatching the secondary antibodies.

Laser confocal microscopy analysis and measurements

Sections were examined with a Leica TCS SP5 confocal laser-scanning microscope (Leica Microsystems, Mannheim, Germany) using a sequential scanning procedure and, when appropriate, an overexposed laser setting. Confocal images were taken at 0.35 µm intervals through the z-axis of the sections, with 40× and 63× oil lenses associated to zoom factors from 1.5 to 3. Single, serial optical planes and z-stacks (projection images) were analyzed by Leica confocal software (Multicolour Package; Leica Microsystems). The size of TNT-like structures was evaluated with LAS-AF SP5 software (Leica Microsystems) on 63× magnification fields zoomed 3 times. TNT thickness (µm) was measured on projection images from fetal cerebral cortex (n = 4), stained for NG2, for a total of 63 TNT fields. The results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD) together with the maximum (Max) and minimum (Min) values.

Pericyte tunneling nanotube assays

Human brain vascular pericytes (HBVP) were purchased from CellScience (CellScience, Research Laboratory, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and cultured in Pericyte Culture Medium (PCM), supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum; Pericytes Growth supplement; 2 mM l-Glutamine and antibiotics (100 U of penicillin G and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin sulphate). Cell cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. At confluence, HBVPs were detached with Accutase (GE Healthcare) and resuspended in complete PCM, then 5 × 104 HBVP were seeded on Matrigel layer and cells were incubated at 37 °C for 5 h. Then medium from each well was gently aspirated and cells were fixed with 100 µl of 4% PFA at 4 °C overnight. The PFA solution was then gently removed and the cells were maintained in PBS containing 0.02% PFA. The relevant in vitro observations were carry out with HBVP at passage 3. The formation of TNTs was documented with a microscope (Eclipse TS100, Nikon Italia) equipped with a CCD camera (DS-Qi1Mc; Nikon Italia), and their diameter was estimated using Nikon NIS software on 20× magnification fields zoomed 3 times. A total of 25 fields was evaluated to assess the average thickness of TNTs. For immunofluorescent staining, HBVP were seeded on glass coverslips pre-coated with gelatine and allow to adhere for 24 h, then fixed in 4% PFA at RT for 20 min and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min. The cells were incubated with the following reagents: Phalloidin TRITC-conjugated (1:500 in PBS, ECM-Biosciences, Versailles, USA; code PF7551), or Lipophilic Cell Tracker Dil (1:200 in PBS, Invitrogen, code C7001). The cells were immunostained with mAb anti-Neural/Glial Antigen2/Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 (NG2/CSPG4, Thermo Fisher Scientific) overnight at 4 °C, revealed by an anti-mouse fluorophore 488-conjugated secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After each incubation step the sections were washed 3 times for 5 min with PBS. The glasses were mounted on Vectashield containing DAPI (Invitrogen) diluted 1 mg/ml in distilled water and images were taken at 20× magnification with an inverted epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axio Observer Z1; Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with a CCD camera (LMS710, Zeiss).

Results

TNTs in human developing cerebral cortex

Triple immunostainings with Glut-1, as a marker of blood brain barrier (BBB)-endothelial cells (ECs), the pericyte marker NG2 proteoglycan, and GFAP for astroglia cells, were carried out to analyze the possible cellular source(s) of TNTs in the developing cerebral cortex (Fig. 2a–d). On these sections, apposed microvessels lined by Glut-1+ BBB-ECs, and typically covered by NG2+ pericytes, appeared embedded in a parenchyma characterized by curtains of GFAP+ astroglia cells (mainly radial glia fibers) and densely packed neuroblast nuclei (Fig. 2a, c). NG2+ TNTs were seen to arise from the microvessel wall directed toward the facing vessel or completely bridging the gap between the vessels (Fig. 2a, c). The pericyte nature and morphological details of the detected TNTs were better demonstrated on the NG2 staining single channel (red; Fig. 2b, d). In the Additional file (Additional file 3a–f), the same cortex fields shown in Fig. 2 are shown on single, separate, staining channels (Glut-1, NG2, and GFAP), without nuclear counterstaining, in B&W, and with the addition of a bas-relief filter, to better demonstrate the exclusive origin of TNTs from pericytes (Additional file 3a, b, d, e) and their tunneling course throughout the dense, cortex parenchyma (Additional file 3c, f). Additional file 4 consists of a sequence of single optical planes (0.35 µm thick each) and the relative structural details of TNT shown in Fig. 2a. The independence of pericyte-derived TNTs from endothelial cells was confirmed by double staining with NG2 and the endothelial marker CD31/PECAM-1 (platelet–endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1) (Fig. 3a–d). On these sections, marker specificity is confirmed, together with the demonstration of ultra-long NG2+, pericyte-derived TNTs (Fig. 3b, c), which in some fields can be followed from one vessel-side to the opposite one (Fig. 3d). An additional movie file (Additional file 5) shows the structure of the TNT depicted in Fig. 3c in more detail: the sequence of 44 serial optical planes (0.35 µm each) allowed the TNT root to be recognized and to follow over its entire length for about 15 µm in the section depth.

Representative confocal microscopy images of blood–brain barrier (BBB)-microvessels and TNTs in the developing human telencephalon at 22 wg. a, c NG2+, pericyte TNTs (arrows) originate from cortex microvessels (V) lined by Glut-1+ BBB-endothelial cells, and pass through a curtain of GFAP+ radial glia fibers; b, d The single channel (red) better shows NG2+ pericytes (PC), which cover the microvessel wall, together with the finer details of their NG2+ TNTs. Nuclear counterstaining SYTOX. Scale bars a, b 25 µm; c, d 20 µm

Representative confocal microscopy images of pericyte TNTs in the developing human telencephalon at 22 wg. a Two microvessels (V) revealed by CD31+ endothelial cells and NG2+ activated pericytes (PC). b, c Bent (b, arrow) and straight (c, arrow) NG2+ TNT originate from pericytes (PC) associated with microvessels (V) lined by CD31+ endothelial cells. d A nearly undetectable, very thin and ultra-long NG2 TNT (arrow) connects a growing microvessel (V), escorted by a leading pericyte (arrowhead), to the recipient vessel (V); the encircled area corresponds to an overexposed laser confocal microscope setting. PC pericyte. Nuclear counterstaining TOPRO-3. Scale bars a–d 20 µm

Extracellular matrix molecules and pericyte-derived TNTs

Further data on the structural composition were collected by analyzing TNT-associated basal lamina (BL) molecules (see the initial observations of FN+ TNTs; Background paragraph). Double staining with NG2 and collagen type IV (Col IV) showed colocalization of the extracellular domain of NG2 with Col IV molecules on the vessel wall and TNT surface (Fig. 4a–d). This was more evident on the TNT root (Fig. 4c, d), whereas on the far TNT extension, NG2 prevailed (Fig. 4b, c). On double staining with Col VI, that is known to bind the extracellular NG2 domain, and Col IV, the former clearly resembled the NG2 extension on the more distant TNT tracts (Fig. 4e, f).

Representative confocal microscopy images of NG2/Col IV and Col VI/Col IV immunostained telencephalon sections from 18 wg (a, f) and 22 wg (b–e) fetuses. a–d NG2 and Col IV extensively colocalize on both vessel basal lamina (VBL) and TNT basal lamina (BL); NG2 staining prevails over the whole TNT extension (a, b, c; arrow), while Col IV appears more concentrated at the TNT root (c, d; arrowhead). e, f Col VI and Col IV extensively colocalize on both VBL and TNT BL, although Col VI seems to prevail on TNTs (arrow), closely resembling the NG2 staining. Nuclear counterstaining TOPRO-3. PC, pericyte. Scale bars a, d, f 25 µm; b, c 20 µm; e 50 µm

CD146 and NG2 identify pericyte TNTs

Additional information on the molecular composition of plasma membranes involved in TNT formation was obtained with another pericyte marker, the single cell-adhesion receptor CD146 (also known as cell surface glycoprotein MUC18). On double staining with NG2, CD146 was shown to colocalize with NG2 over the entire extension of pericytes’ TNTs (Fig. 5a–d). On the finest and more distant TNT tracts, CD146 staining prevailed and NG2 was detected as a few scattered molecules on the TNT surface (Fig. 5c). Interestingly, double CD146/NG2 staining also showed larger conduits, where CD146 and NG2 were colocalized on the innermost TNT surface, while NG2, as a transmembrane molecule characterized by a large extracellular domain, also marked the outer surface (Fig. 5d). In Additional file 6, on this type of TNTs showing the sequence of single optical planes (from the projection image of Fig. 5d), we could recognize the cytoplasm inside the TNT, which seems to permit the passage of a cell nucleus (Additional file 6).

Representative confocal microscopy images of NG2/CD146 immunostained pericyte TNTs in the developing human telencephalon at 22 wg. a A very thin, double stained TNT, revealed by the overexposed laser confocal microscope setting (encircled area), originates from an NG2+/CD146+ pericyte (PC). b, c NG2 and CD146 extensively colocalized along the entire extension of pericytes TNTs (arrows), although on the TNT distant ends CD146 staining prevails. d An NG2+/CD146+ larger TNT conduit (arrow) appears to connect the tip of a growing microvessel (V), escorted by a leading pericyte (PC), with a recipient vessel (V); note a nucleus (arrowhead) that apparently fills the TNT end (see also Additional file 6). Nuclear counterstaining TOPRO-3. PC, pericyte. Scale bars a, d 10 µm; b, c 25 µm

TNTs and cerebral cortex vascularization

Based on the results obtained with CD146+/NG2+ TNTs, fields of vessel growth and sprouting were searched for and analyzed utilizing CD105 (endoglin), a molecule involved in angiogenesis and specifically expressed by proliferating ECs and by sprouting endothelial tip cells (ETCs) (Additional file 7; see also [25]). On double CD105/CD146 and NG2/CD146 immunostainings (Fig. 6a–f; Additional file 7), CD146+ TNTs were seen to originate from the leading pericytes of two facing vessel sprouts (Fig. 6a, b), while stalk ECs and ETCs expressed high levels of CD105, although the latter did not seem to be involved in TNT formation (Fig. 6a, c), and phalanx EC were weakly stained by CD105 (Fig. 6a, c). The pericyte origin of CD146+ TNTs that were seen to connect vessel sprouts was confirmed by double staining, which showed CD146 to colocalize with NG2 on leading pericyte-like cells and on their short TNTs (Fig. 6d–f).

Representative confocal microscopy images of pericyte TNT involved in vessel growth and sprouting in the developing human telencephalon at 22 wg (a–c) and 18 wg (d–f). a–c CD105/CD146 and d–f NG2/CD146 double immunostainings. a–c Comparison of the merged image (a) with single channels (b, c) allows a ‘complete’ vessel sprout to be identified, formed by a CD146+ escorting pericyte (PC in a and b) and a CD105+ endothelial cell (arrowhead in a, c) and a CD146+, pericyte-like sprout (star in a and b), that does not stain positive for CD105, connected by a CD146+ pericyte-like TNT (arrow in a and b); the encircled area in b corresponds to an overexposed laser confocal microscope setting. d–f NG2 colocalized with CD146 on a leading pericyte (PC) and on its short TNT (arrow). Nuclear counterstaining TOPRO-3. Scale bars a–f 25 µm

TNTs and glioblastoma vascularization

One of the histopathological features of GBs is a prominent microvascular proliferation with an abundance of disorganized microvessels and the aggressive proliferation of ECs and pericytes. Because GBs are highly vascularized tumors, a parallel study on TNTs was conducted on human GB samples (Fig. 7a–d), to ascertain whether, as observed during normal brain vascularization, ‘vascular’ TNTs form between vessels also in pathological tumoral angiogenesis. Although ECM molecules did not allow the cell of origin of TNTs to be identified, the molecules that were used in fetal cerebral cortex samples did indeed show a very high sensitivity in revealing TNTs. For this reason and braced by the previous results, which showed a good correspondence between NG2 and Col IV, we decided to approach the study by performing double immunostaining of human GB sections with CD31 and Col IV (Fig. 7a–d). Among the different types of microvascular formations described [26, 27], tumoral microvascular sprouting has been defined as characterized by the proliferation of delicate capillary-like microvessels resembling those seen during classic angiogenesis, distributed evenly throughout the major parts of vital tumor tissue. When analyzed on CD31/Col IV stained sections, these tumoral areas showed a rich network of TNTs that extensively connected distant capillary-like tumoral vessels (Fig. 7a–f), which closely resembled the thinner forms of TNTs observed in the developing cortex.

Representative confocal microscopy images of human glioblastoma sections immunostained for CD31 and Col IV. a, c, e Col IV+ TNTs (arrows) connect capillary-like tumor vessels (V); note in c and e the weak CD31 staining of tumoral endothelial cells. b, d, f On the single Col IV channel (red) the continuity of TNTs is better shown. Nuclear counterstaining TOPRO-3. Scale bars a, b 25 µm; c–f, 20 µm

Pericyte TNTs in cultures

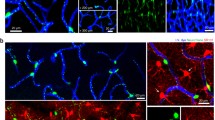

The authenticity of the pericyte TNTs observed in the fetal brain was largely confirmed by the ability of isolated brain vascular pericytes to reproduce such structures in vitro. In fact, when pericytes were cultured in Matrigel (in conditions promoting tube formation of endothelial cells), the arrangement of pericytes and pseudo-tubular structures could be observed, demonstrating that single cells or groups of cells were frequently connected by TNT-like structures of various lengths (Fig. 8a–f). Fluorescent vital staining of the pericytes with the lipophilic dye, DiI (Fig. 8f), confirmed that the observed cell filopodial processes did indeed emanate through extensions of the plasma membrane, while Phalloidin labeling confirmed that they were sustained by actin microfilament bundles (Fig. 8b, e). Finally, immunostaining with antibodies to NG2/CSPG4 further corroborated this view, since the nanotubes were decorated by the proteoglycan (Fig. 8c, f).

Human brain vascular pericytes (HBVP) TNTs in vitro. a, d Representative TNT networking among HBVP cultured on Matrigel layer. b, e Filaments of actin contained in HBVP-derived TNTs stained with Phalloidin TRITC-conjugated dye. c, f NG2/CSPG4 immunostaining of pericytes (green), pretreated with Phalloidin TRITC-conjugated dye (c, red), or with lipophilic DiI cell tracker (f, red), shows long NG2+ TNTs (arrows). Nuclear counterstaining DAPI (b, c, e, f). Scale bars a, b, d, e 50 µm; c, f 25 µm

TNTs measurement in situ and in vitro

Measurements were carried out on randomly chosen, NG2 stained sections (n = 13) of fetal cerebral cortex (n = 4) for a total of 63 TNT fields. The resulting estimated thickness was 1.614 ± 0.718 µm (M ± SD), and Max and Min values were 2.9 µm and 0.34 µm, respectively. Size assessment of pericyte TNTs in in vitro assays indicated an average thickness of 1.88 ± 0.25 μm.

Discussion

It has been demonstrated that pericytes contribute to the barrier phenotype of brain ECs and that they are involved in the formation and regulation of the BBB [28, 29]. It is also well known that vascularization of the central nervous system (CNS) occurs via an angiogenic mechanism of vessel sprouting from the pre-existing vessels of the perineuronal vascular plexus and from the perforating, intraparenchymal, radial vessels [30, 31]. It has been underlined in several studies that pericytes are recruited through classic PDGF/PDGFR-β-mediated signaling, after the active phase of vessel sprouting, mainly directed by stalk and tip endothelial cells, having the effect of stabilizing the growing vessel, favoring EC BBB differentiation [32]. On the other hand, it has also been observed that in pathological conditions, as well as in normal developing CNS, NG2+/PDGFR-β+ pericytes closely cover CD31+ ECs, spanning the gap between neighboring endothelial cell sprouts, being tightly associated with CD31+ ETCs [33, 34]. In their study [33], the Authors stressed the need for ‘more detailed investigation in future work’ on the detected ‘putative pericyte bridges’. Immature pericytes have been described in association with the tips of capillary sprouts in the mesenteric microvascular bed [35] and also seen at and in front of the advancing tips of endothelial sprouts, as well as bridging the gap between the leading edges of opposing endothelial sprouts which were apparently preparing to merge [36]. We have previously demonstrated that during fetal brain vascularization, NG2+/PDGFR-β+ angiogenic/activated pericytes seem to be involved in the early phases of angiogenesis, appearing in extensive association with the telencephalon vasculature, and in intimate contact with vascular sprouts [37]. This suggests that during CNS angiogenesis, the sprouting phase of nascent vessels is controlled by an intimate interplay between escorting pericytes and ETCs and that guiding (pioneering) pericytes may initiate the angiogenic process by forming strands connecting to existing capillaries [37, 38]. More recently, pericytes have been suggested to promote endothelial sprouting by producing hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) [39], and the hypothesis has been advanced that like stalk and tip endothelial cells, so also pericytes can recognize different subpopulations that accomplish different, specific roles, including making an active contribution to endothelial sprouting [40]. Certainly pericyte subpopulations exist, also stemming from different cell precursors, and the origin of forebrain pericytes from cephalic neural crest cells [41] may explain the mesenchymal potential and phenotypic and functional singularity of brain pericytes, including their participation in the earliest stages of neovascularization [42, 43]. The searching, guiding, and communicating activities played by pericyte-derived TNTs while aiding the outgrowth of endothelial cells may be included in this scenario.

TNTs and Basal lamina molecule relationships

Intriguingly, extending nanotubes appear fully enwrapped by a complex ECM, composed by fibronectin, Col IV and Col VI. Pericytes have been identified as important players in regulating basement membrane organization, in particular the deposition, during development, of fibronectin, laminin and collagen IV, which may be key molecules in regulating pericyte-ECs connections [43]. Pericyte TNTs carry the transmembrane proteoglycan NG2/CSPG4, and the link between the large extracellular domain of this molecule and Col VI [44] may contribute to TNTs’ basal lamina (BL) organization. The BL molecules associated to TNTs may provide mechanical support to the extending cell nanostructures, and also mediate signaling and mechanical strains [45] between cells over long distances.

Pericyte TNTs at point of vessel sprouting and vessel collateralization

It could be suggested that the reason for a precocious involvement of pericyte TNTs during angiogenesis is to allow an indispensable cell-to-cell recognition and communication during both physiological (developing brain) and pathological (glioblastoma) neovascularization. During the early phases of vessel growth, pericyte TNTs may send molecular messages and/or organelles to the receiving cell (pericyte, EC, or other?) in the targeted vessel (e.g. between two distant vessels) or originating from an ETC-escorting pericyte, may guide sprout-to-vessel and sprout-to-sprout recognition and crosstalk. In addition, TNTs were also seen bridging the gap between CD146+/CD105− and CD146+/CD105+ vessel sprouts. This observation closely resembles the long ‘endothelial’ filopodia described by Thomas Bär (see Additional file 1). The nature of the sprout-connecting long filopodia can be discussed in the light of the recent data gained on CD146 dynamic expression in ECs and pericytes during brain development. At this stage CD146 has been demonstrated to be expressed by ‘naked’, immature ECs, while in microvessels covered with pericytes CD146 appeared exclusively expressed by pericytes, which are induced to express high levels of CD146 in parallel with a TGF-β pericyte-derived downregulation of CD146 in ECs [46]. Interestingly, Cd146-KO mice and Cd146PC-KO, compared with Cd146EC−KO, showed a reduction in pericyte coverage and an abnormal BBB development (abnormal tight junctions/claudin-5 expression). In fact, CD146, which is constitutively expressed by brain pericytes, appeared to be involved in pericyte recruitment, working as a coreceptor in the PDGF-B/PDGFR-β signaling [46]. CD105/endoglin is a homodimeric transmembrane glycoprotein that is strongly expressed on endothelial precursor cells [47] and angiogenically activated endothelial cells, and is involved in vascular development and remodeling [48], showing a 50% reduced ratio with PECAM in normal vessels of newborn brain [49]. In fact, at the protein level, during fetal brain angiogenesis CD105 appears strongly expressed by ETCs, thus making the typical ETC’s filopodial protrusions recognizable (Additional file 7; see also [25]). Although it is claimed that no surface markers exclusively expressed by pericytes exist [50], pericytes can be identified by coexpressing canonical pericyte markers, CD146 and NG2 [51]. Together with the absence of CD105, these data strongly suggest the existence in brain tissue, in vivo, of sprouting cells with a pericyte-like phenotype, and of couples of hetero-sprouts, involved in vessel branching and possibly connected by pericyte TNT-like cell protrusions. This is consistent with previous observations that assigned a leading role to pericytes in vessel sprouting during human cerebral cortex development, and demonstrated pericytes initiating sprouting, and forming long strands between existing capillaries [38].

TNTs vs microtubes (MT): simple cousins or connected structures?

Double NG2/CD146 staining also showed a larger subset of pericyte TNTs, that can be regarded as the big cousins of the classical tiny structures. As suggested for tumor microtubes (TMs), the latter likewise promote tumor aggressiveness and therapeutic resistance [21, 52]. In vivo microscopy methods made it possible to discover highly dynamic, large and long (cross-sectional area 1.57 ± 0.33 µm2, and more than 500 µm in length) glioblastoma cell TNT-like protrusions, TMs, scanning the surrounding microenvironment, carrying mitochondria and microvesicles and, after mitosis, traveling daughter cell nuclei [52, 53]. Although only based on ‘static’ confocal microscopy images rather than live imaging, the hypothesis may be advanced that the large, ultra-long TNTs observed during normal fetal neuroangiogenesis, and seen to host cell nuclei, are possibly channeling the nucleus of daughter pericytes (see Additional file 6).

Pericyte TNTs in pericyte-to-pericyte and pericyte-to-endothelial cell communication

We have previously demonstrated that in human GB, NG2 and Col IV are extensively colocalized on pericyte layer/s of both capillary-like microvessels and glomeruloid structures [24]. In the present study, Col IV+/CD31− TNTs have been demonstrated, connecting tumoral vessels marked by endothelial CD31, suggesting that as observed in normal brain vascularization, ‘vascular’ TNT nanostructures that span the gap between tumoral vessels, can likewise be involved in pathological tumoral angiogenesis. Interestingly, membrane protrusions identified as TNTs with a mural cell (smooth muscle cells and pericytes) origin have been shown to be able to transfer microRNAs to ECs and modulate their angiogenesis and vessel stabilization properties [54]. Origin and ‘recipient’ cells of the observed GB TNTs need to be further investigated, although if they are considered in parallel with TNTs observed during normal angiogenesis, and in the light of in vitro studies a specific role can be postulated also in tumor angiogenesis. Interestingly, recent studies conducted by confocal live cell imaging of myeloid-derived cells in corneal explants from Cx(3)cr1(GFP) and CD11c(eYFP) transgenic mice have revealed that, unlike in in vitro studies, where nanotubes originate from cell–cell contacts, in in vivo tissue, these structures form de novo as a response to specific ‘stress’ factors at a rate of 15.5 μm/min [55]. These results support our thesis that TNTs may also be elicited by growth factors involved in angiogenesis events. Equally relevant findings, for the scope of our study, emerge from the analysis of TNT-dependent electrical coupling between developing embryonic cells, and the potential implication of this TNT role in cell-to-cell signaling in developmental processes [56]. It must not be forgotten that direct pericyte–endothelial contact is established via junctional complexes located at peg–socket contacts, which also contain gap junctions [see for a review on ‘Endothelial/Pericyte Interactions’ Armulik et al. [43]. Therefore, it cannot be excluded that blind-ended TNTs provided with gap junction components may mediate pericyte-endothelial communication between distant, growing vessels.

Conclusions

Overall, the present data provide further evidence and different examples of TNTs and/or TNT-like microstructures in human brain development and in human GB, adding another tile to the documented existence of TNTs in tissues in vivo (see Ariazi et al. for a recent Review [57]). Moreover, our findings reveal a possible novel role for brain pericytes that, by giving origin to TNTs, may be involved in the earliest phases, in searching, recognition, connection, and communication, during normal and pathological angiogenesis, thus stressing the leading role of pericytes demonstrated in previous studies [37, 38]. Metastatic invasiveness has recently been associated to TNT horizontal transfer of miRNA between metastatic cancer cells and endothelial cells [58]. Pericyte TNTs in glioblastoma may open out the vista of a possible TNT-based communication between vessel cell components (pericytes, endothelial cells), which may contribute to the suggested MT-dependent chemotherapy resistance [12, 18, 19, 52].

Abbreviations

- BB:

-

blocking buffer

- BBB:

-

blood–brain barrier

- BL:

-

basal lamina

- CNS:

-

central nervous system

- Col IV:

-

collagen type IV

- Col VI:

-

collagen type VI

- DAPI:

-

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- ECM:

-

extracellular matrix

- EC:

-

endothelial cell

- ETC:

-

endothelial tip cell

- FBS:

-

fetal bovine serum

- FCS:

-

fetal calf serum

- FN:

-

fibronectin

- GB:

-

glioblastoma

- GFAP:

-

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- Glut-1:

-

glucose transporter isoform 1

- HBVP:

-

human brain vascular pericytes

- mAb:

-

monoclonal antibodies

- NG2/CSPG4:

-

neuron-glial antigen 2/chondroitin sulphate proteoglycan 4

- pAb:

-

polyclonal antibodies

- PBS:

-

phosphate-buffered saline

- PCM:

-

pericyte culture medium

- PDGF-B:

-

platelet-derived growth factor subunit B

- PDGFR-β:

-

β-type platelet-derived growth factor receptor

- PECAM-1:

-

platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1

- PFA:

-

paraformaldehyde

- PI:

-

propidium iodide

- RNase:

-

ribonuclease

- TGF-β:

-

transforming growth factor β

- TNT:

-

tunneling nanotube

- TRITC:

-

tetramethylrhodamine-isothiocyanate

- VBL:

-

vessel basal lamina

- wg:

-

weeks of gestation

References

Rustom A, Saffrich R, Markovic I, Walther P, Gerdes HH. Nanotubular highways for intercellular organelle transport. Science. 2004;303:1007.

Bär T. The vascular system of the cerebral cortex. In: Adv Anat Embryo Cell Biol. Vol. 59, Berlin: Springer; 1980.

Gerdes H-H, Rustom A. Tunneling nanotubes: membranous channels between animal cells. In: Baluska F, Volkmann D, Barlow PW, editors. Cell-Cell Channels. Landes Bioscience/Springer: Science + Business Media; 2006. p. 200–7.

Gerdes HH, Bukoreshtliev NV, Barroso JF. Tunneling nanotubes: a new route for the exchange of components between animal cells. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2194.

Gerdes HH, Carvalho RN. Intercellular transfer mediated by tunneling nanotubes. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:470.

Veranič P, Lokar M, Schütz GJ, Weghuber J, Wieser S, Hägerstrand H, Kralj-Iglic V, Iglic A. Different types of cell-to-cell connections mediated by nanotubular structures. Biophys J. 2008;95:4416.

Lokar M, Kabaso D, Resnik N, Sepčić K, Kralj-Iglič V, Veranič P, Zorec R, Iglič A. The role of cholesterol–sphingomyelin membrane nanodomains in the stability of intercellular membrane nanotubes. Int J Nanomed. 2012;7:1891.

Abounit S, Zurzolo C. Wiring through tunneling nanotubes-from electrical signals to organelle transfer. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:1089.

Austefjord MW, Gerdes HH, Wang X. Tunneling nanotubes: diversity in morphology and structure. Commun Integr Biol. 2014;7:e27934.

Chinnery HR, Pearlman E, McMenamin PG. Cutting edge: membrane nanotubes in vivo: a feature of MHC class II+ cells in the mouse cornea. J Immunol. 2008;180(9):5779.

Lou E, Fujisawa S, Barlas A, Romin Y, Manova-Todorova K, Moore MA, Subramanian S. Tunneling Nanotubes: a new paradigm for studying intercellular communication and therapeutics in cancer. Commun Integr Biol. 2012;5(4):399.

Pasquier J, Guerrouahen BS, Al Thawadi H, Ghiabi P, Maleki M, Abu-Kaoud N, et al. Preferential transfer of mitochondria from endothelial to cancer cells through tunneling nanotubes modulates chemoresistance. J Transl Med. 2013;11:94.

Antanavičiūtė I, Rysevaitė K, Liutkevičius V, Marandykina A, Rimkutė L, Sveikatienė R, et al. Long-distance communication between laryngeal carcinoma cells. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(6):e99196.

Okafo G, Prevedel L, Eugenin E. Tunneling nanotubes (TNT) mediate long-range gap junctional communication: implications for HIV cell to cell spread. Sci Rep. 2017;7:16660.

Panasiuk M, Rychlowki M, Derewońko N, Bieńkowska-Szewczyk K. Tunneling nanotubes as a novel route of cell-to-cell spread of Herpesviruses. J Virol. 2018;92:e00090.

Dupont M, Souriant S, Lugo-Villarino G, Maridonneau-Parini I, Vérollet C. Tunneling nanotubes: intimate communication between myeloid cells. Front Immunol. 2018;9:438.

Shen J, Zhang J-H, Xiao H, Wu J-M, He K-M, Lv Z-Z, et al. Mitochondria are transported along microtubules in membrane nanotubes to rescue distressed cardiomyocytes from apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:81.

Sahoo P, Jena SR, Samanta L. Tunneling nanotubes: a versatile target for cancer therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2018;18(6):514.

Winkler F, Wick W. Harmful networks in the brain and beyond. Science. 2018;359(6380):1100.

Abounit S, Bousset L, Loria F, Zhu S, de Chaumont F, Pieri L, et al. Tunneling nanotubes spread fibrillar α-synuclein by intercellular trafficking of lysosomes. EMBO J. 2016;35(19):2120.

Rostami J, Holmqvist S, Lindström V, Sigvardson J, Westermark GT, Ingelsson M, et al. Human astrocytes transfer aggregated alpha-synuclein via tunneling nanotubes. J Neurosci. 2017;37(49):11835.

Norman MG, O’Kusky JR. The growth and development of microvasculature in human cerebral cortex. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1986;45:222.

Virgintino D, Errede M, Rizzi M, Girolamo F, Strippoli M, Wälchli T, et al. The CXCL12/CXCR4/CXCR7 ligand-receptor system regulates neuro-glio-vascular interactions and vessel growth during human brain development. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013;36(3):455.

Girolamo F, Dallatomasina A, Rizzi M, Errede M, Wälchli T, Mucignat MT, et al. Diversified expression of NG2/CSPG4 isoforms in glioblastoma and human foetal brain identifies pericyte subsets. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e84883.

Virgintino D, Rizzi M, Errede M, Strippoli M, Girolamo F, Bertossi M, et al. Plasma membrane-derived microvesicles released from tip endothelial cells during vascular sprouting. Angiogenesis. 2012;15(4):761.

Birner P, Piribauer M, Fischer I, Gatterbauer B, Marosi C, Ambros PF, et al. Vascular patterns in glioblastoma influence clinical outcome and associate with variable expression of angiogenic proteins: evidence for distinct angiogenic subtypes. Brain Pathol. 2003;13:133.

Yue WY, Chen ZP. Does vasculogenic mimicry exist in astrocytoma? J Histochem Cytochem. 2005;53:997.

Armulik A, Genové G, Mäe M, Nisancioglu MH, Wallgard E, Niaudet C, et al. Pericytes regulate the blood–brain barrier. Nature. 2010;468(7323):557.

Daneman R, Zhou L, Kebede AA, Barres BA. Pericytes are required for blood–brain barrier integrity during embryogenesis. Nature. 2010;468(7323):562.

Risau W. Mechanisms of angiogenesis. Nature. 1997;386(6626):671.

Engelhardt B. Development of the blood–brain barrier. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;314(1):119.

Hellström M, Kalén M, Lindahl P, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C. Role of PDGF-B and PDGFR-beta in recruitment of vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes during embryonic blood vessel formation in the mouse. Development. 1999;126(14):3047.

Ozerdem U, Monosov E, Stallcup WB. NG2 proteoglycan expression by pericytes in pathological microvasculature. Microvasc Res. 2002;63(1):129.

Ozerdem U, Grako KA, Dahlin-Huppe K, Monosov E, Stallcup WB. NG2 proteoglycan is expressed exclusively by mural cells during vascular morphogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2001;222(2):218.

Rhodin JA, Fujita H. Capillary growth in the mesentery of normal young rats. Intravital video and electron microscope analyses. J Submicrosc Cytol Pathol. 1989;21(1):1.

Nehls V, Denzer K, Drenckhahn D. Pericyte involvement in capillary sprouting during angiogenesis in situ. Cell Tissue Res. 1992;270(3):469.

Virgintino D, Girolamo F, Errede M, Capobianco C, Robertson D, Stallcup WB, et al. An intimate interplay between precocious, migrating pericytes and endothelial cells governs human fetal brain angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2007;10:35.

Virgintino D, Ozerdem U, Girolamo F, Roncali L, Stallcup WB, Perris R. Reversal of cellular roles in angiogenesis: implications for anti-angiogenic therapy. J Vasc Res. 2008;45:129.

Chang WG, Andrejecsk JW, Kluger MS, Saltzman WM, Pober JS. Pericytes modulate endothelial sprouting. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;100(3):492.

Stapor PC, Sweat RS, Dashti DC, Betancourt AM, Murfee WL. Pericyte dynamics during angiogenesis: new insights from new identities. J Vasc Res. 2014;51:163.

Etchevers HC, Vincent C, Le Douarin NM, Couly GF. The cephalic neural crest provides pericytes and smooth muscle cells to all blood vessels of the face and forebrain. Development. 2001;128(7):1059.

Ozerdem U, Alitalo K, Salven P, Li A. Contribution of bone marrow-derived pericyte precursor cells to corneal vasculogenesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(10):3502.

Armulik A, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C. Endothelial/pericyte interactions. Circ Res. 2005;97(6):512.

Cattaruzza S, Nicolosi PA, Braghetta P, Pazzaglia L, Benassi MS, Picci P, et al. NG2/CSPG4-collagen type VI interplays putatively involved in the microenvironmental control of tumour engraftment and local expansion. J Mol Cell Biol. 2013;5(3):176.

Yurchenco PD. Basement membranes: cell scaffoldings and signaling platforms. Cold Spring Harbor Persp Biol. 2011;3(2):a004911.

Chen J, Luo Y, Hui H, Cai T, Huang H, Yang F, et al. CD146 coordinates brain endothelial cell–pericyte communication for blood–brain barrier development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(36):E7622.

Bagley RG, Weber W, Rouleau C, Teicher BA. Pericytes and endothelial precursor cells: cellular interactions and contributions to malignancy. Cancer Res. 2005;65(21):9741.

Nassiri F, Cusimano MD, Scheithauer BW, Rotondo F, Fazio A, Yousef GM, et al. Endoglin (CD105): a review of its role in angiogenesis and tumor diagnosis, progression and therapy. Anticancer Res. 2011;31(6):2283.

Bourdeau A, Cymerman U, Paquet ME, Meschino W, McKinnon WC, Guttmacher AE, et al. Endoglin expression is reduced in normal vessels but still detectable in arteriovenous malformations of patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1. Am J Pathol. 2000;156(3):911.

Armulik A, Genové G, Betsholtz C. Pericytes: developmental, physiological, and pathological perspectives, problems, and promises. Dev Cell. 2011;21(2):193.

Loibl M, Binder A, Herrmann M, Duttenhoefer F, Richards RG, Nerlich M, et al. Direct cell–cell contact between mesenchymal stem cells and endothelial progenitor cells induces a pericyte-like phenotype in vitro. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:395781.

Osswald M, Jung E, Sahm F, Solecki G, Venkataramani V, Blaes J, et al. Brain tumour cells interconnect to a functional and resistant network. Nature. 2015;528(7580):93.

Rehberg M, Nekolla K, Sellner S, Praetner M, Mildner K, Zeuschner D, et al. Intercellular transport of nanomaterials is mediated by membrane nanotubes in vivo. Small. 2016;12(14):1882.

Climent M, Quintavalle M, Miragoli M, Chen J, Condorelli G, Elia L. TGFb triggers miR143/145 transfer from smooth muscle cells to endothelial cells, thereby modulating vessel stabilization. Circ Res. 2015;116:1753.

Seyed-Razavi Y, Hickey MJ, Kuffová L, McMenamin PG, Chinnery HR. Membrane nanotubes in myeloid cells in the adult mouse cornea represent a novel mode of immune cell interaction. Immunol Cell Biol. 2013;91(1):89.

Gerdes HH, Rustom A, Wang X. Tunneling nanotubes, an emerging intercellular communication route in development. Mech Dev. 2013;130(6–8):381.

Ariazi J, Benowitz A, De Biasi V, Den Boer ML, Cherqui S, Cui H, et al. Tunneling nanotubes and gap junctions-their role in long-range intercellular communication during development, health, and disease conditions. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017;10:333.

Connor Y, Tekleab S, Nandakumar S, Walls C, Tekleab Y, Husain A, et al. Physical nanoscale conduit-mediated communication between tumour cells and the endothelium modulates endothelial phenotype. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8671.

Authors’ contributions

ME carried out fetal tissue immunostaining and designed the specific IHC protocols, drafted the manuscript; DM carried out in vitro experiments and documentation, drafted the manuscript; GL and DV carried out confocal observations on fetal tissue; FG and IdT carried out glioblastoma tissue immunostaining and confocal observations and measurements; AV and GS prepared and analyzed fetal brains; KF prepared and analyzed glioblastoma samples; RP reviewed the manuscript, DV drafted and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Prof. Joan Abbott for helpful discussions and Prof. Bill Stallcup for the generous NG2D2 antibody gift. They would like to thank M.V.C. Pragnell, BA, for language help, Marisa Ambrosi, Francesco Fumai and Michelina de Giorgis for general laboratory infrastructure and technical assistance.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval

Samples of fetal brain were obtained from four post-mortem fetuses derived from spontaneous abortions and received by the Department of Emergency and Organ Transplantation, Division of Pathology, University of Bari School of Medicine. All samples used here were taken post-mortem. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Bari Medical School and complied with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. Tissue samples from glioblastoma patients were obtained during surgery at the Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital Zurich. Written informed consent was obtained from patients before study entry. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Canton Zurich.

Funding

This work was supported by Fondazione Puglia (2015) to DV.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1.

Formation of TNTs during the process of vessel sprouting. a Part of the original diagram from Bär [2] that summarizes the formation of net-capillaries in the cerebral cortex; the step denoted ‘fusion’ is described as “A fusion of capillary sprouts with preexisting capillaries or with another sprout may be initiated by contact of small endothelial tentacles.” (Springer Nature License to Daniela Virgintino, Bari University School of Medicine). b Similar facing sprouts connected by a TNT are revealed by confocal microscopy and CD146/CD105 immunostaining in the fetal cerebral cortex (see also Fig. 6 and the Result paragraph). Scale bar b, 25 µm.

Additional file 2.

Additional examples of straight and spiraled TNTs immunostained with fibronectin (FN). a Two parallel, tiny and ultra-long FN+ TNTs (arrows), whose continuity is revealed in the FN single channel (b). c, d A typical bridging TNT (arrows) e, f A TNT characterized by an irregular course (arrow), clearly originates from a pericyte (PC). Nuclear counterstaining propidium iodide (PI). Scale bars a, b 50 µm; c–f 25 µm.

Additional file 3.

A single channel, grayscale, bas-relief image of Fig. 2a, c. The digital filters applied to pictures a and b in Fig. 2, highlight the endothelial profile (a, d), the pericyte origin of TNTs (b, e), and their excavated course (tunneling) through the dense, fetal cerebral cortex parenchyma (c, f; arrows). Scale bars a, b 25 µm; c, d 20 µm.

Additional file 4.

Single optical planes show TNT details and relationship. Sequence of single optical planes from the z-stack of Fig. 2a.

Additional file 5.

Following the TNT deep into section thickness. TNT depicted in Fig. 3c (projection image) results from the sequence of 44 optical planes through the entire section thickness (about 15 µm).

Additional file 6.

Does the large TNTs convey cell nuclei? Sequence of single optical planes from the z-stack of Fig. 5d, shows the TNT plasma membrane and a cell nucleus inside the TNT.

Additional file 7.

CD105 is a marker of angiogenically activated endothelial tip cells in the fetal cerebral cortex. a–c Examples of CD105+ activated. d–f Examples of CD105+ endothelial cells, covered by CD146+ pericytes (PC). Nuclear counterstaining TOPRO-3. Scale bar a, b, d 20 µm; c, e, f 10 µm.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Errede, M., Mangieri, D., Longo, G. et al. Tunneling nanotubes evoke pericyte/endothelial communication during normal and tumoral angiogenesis. Fluids Barriers CNS 15, 28 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12987-018-0114-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12987-018-0114-5