Abstract

Background

When certain complications arise during the second stage of labour, assisted vaginal delivery (AVD), a vaginal birth with forceps or vacuum extractor, can effectively improve outcomes by ending prolonged labour or by ensuring rapid birth in response to maternal or fetal compromise. In recent decades, the use of AVD has decreased in many settings in favour of caesarean section (CS). This review aimed to improve understanding of experiences, barriers and facilitators for AVD use.

Methods

Systematic searches of eight databases using predefined search terms to identify studies reporting views and experiences of maternity service users, their partners, health care providers, policymakers, and funders in relation to AVD. Relevant studies were assessed for methodological quality. Qualitative findings were synthesised using a meta-ethnographic approach. Confidence in review findings was assessed using GRADE CERQual. Findings from quantitative studies were synthesised narratively and assessed using an adaptation of CERQual. Qualitative and quantitative review findings were triangulated using a convergence coding matrix.

Results

Forty-two studies (published 1985–2019) were included: six qualitative, one mixed-method and 35 quantitative. Thirty-five were from high-income countries, and seven from LMIC settings. Confidence in the findings was moderate or low. Spontaneous vaginal birth was most likely to be associated with positive short and long-term outcomes, and emergency CS least likely. Views and experiences of AVD tended to fall somewhere between these two extremes. Where indicated, AVD can be an effective, acceptable alternative to caesarean section. There was agreement or partial agreement across qualitative studies and surveys that the experience of AVD is impacted by the unexpected nature of events and, particularly in high-income settings, unmet expectations. Positive relationships, good communication, involvement in decision-making, and (believing in) the reason for intervention were important mediators of birth experience. Professional attitudes and skills (development) were simultaneously barriers and facilitators of AVD in quantitative studies.

Conclusions

Information, positive interaction and communication with providers and respectful care are facilitators for acceptance of AVD. Barriers include lack of training and skills for decision-making and use of instruments.

Abstrait

Contexte

Lors de complications au cours du deuxième stade du travail, l’utilisation de forceps ou d’une ventouse peut améliorer l’issue de l’accouchement par voie basse en assurant une naissance rapide lorsque la mère ou le fœtus se trouvent en difficulté. Au cours des dernières décennies, l’utilisation de l’accouchement assisté par voie basse a diminué dans de nombreuses régions en faveur de la césarienne. Cette revue vise à mieux comprendre les expériences et les facteurs qui facilitent ou empêchent l’utilisation de l’accouchement assisté par voie basse.

Méthodes

Recherches systématiques dans huit bases de données à l’aide de termes de recherche prédéfinis pour identifier les études rapportant les points de vue et les expériences des utilisatrices de services de maternité, de leurs partenaires, des prestataires de soins de santé, des responsables politiques et des bailleurs de fonds en rapport avec l’accouchement assisté par voie basse. La qualité méthodologique des études pertinentes a été évaluée. Les résultats qualitatifs ont été synthétisés à l’aide d’une approche méta-ethnographique. La confiance envers les résultats de l’examen a été évaluée à l’aide de l’approche GRADE CERQual. Les résultats des études quantitatives ont été synthétisés de manière narrative et évalués à l’aide d’une adaptation de CERQual. Les résultats des examens qualitatifs et quantitatifs ont été triangulés à l’aide d’une matrice de codage des convergences.

Résultats

42 études (publiées de 1985 à 2019) ont été incluses: six qualitatives, une mixte et 35 quantitatives. Trente-cinq provenaient de pays à revenus élevés et sept de pays à revenus faibles ou intermédiaires. La confiance envers les résultats était modérée ou faible. L’accouchement spontané par voie basse était le plus susceptible d’être associé à des résultats positifs à court et à long terme, et la césarienne d’urgence la moins susceptible de l’être. Les opinions et les expériences relatives à l’accouchement assisté par voie basse se situaient généralement entre ces deux extrêmes. Sur indication médicale, l’accouchement assisté par voie basse peut être une alternative efficace et acceptable à la césarienne. Les études qualitatives et les enquêtes s’accordent de façon totale ou partielle sur le fait que l’expérience de l’accouchement assisté par voie basse est. affectée par la nature inattendue des événements et, en particulier dans les pays à revenu élevé, les attentes non satisfaites. Des relations positives, une bonne communication, une participation à la prise de décision et (une foi en) la raison de l’intervention étaient d’importants médiateurs de l’expérience de l’accouchement. Les attitudes et (le développement des) compétences professionnelles étaient simultanément des obstacles et des facilitateurs de l’accouchement assisté par voie basse dans les études quantitatives.

Conclusion

L’information, l’interaction positive et la communication avec les prestataires ainsi que les soins respectueux facilitent l’acceptation de l’accouchement assisté par voie basse. Les obstacles comprennent le manque de formation et de compétences pour la prise de décision et l’utilisation d’instruments.

Resumen

Antecedentes

Cuando surgen ciertas complicaciones durante la segunda etapa del parto, el parto vaginal asistido, es decir, un parto vaginal con fórceps o ventosa, puede mejorar efectivamente los resultados al poner fin a un parto prolongado o asegurar un parto más rápido en caso de riesgo para la madre o el feto. En las últimas décadas, el uso del parto vaginal asistido ha disminuido en muchos entornos en favor de la cesárea. Esta revisión tuvo como objetivo mejorar la comprensión de las experiencias, los obstáculos y los elementos facilitadores para el uso del parto vaginal asistido.

Métodos

Búsquedas sistemáticas en ocho bases de datos utilizando términos de búsqueda predefinidos para identificar estudios que aportaran puntos de vista y experiencias de usuarias de servicios de maternidad, sus parejas, proveedores de atención médica, responsables de la formulación de políticas y entidades financiadoras en relación con el parto vaginal asistido. Se evaluó la calidad metodológica de los estudios. Los hallazgos cualitativos se sintetizaron utilizando un enfoque meta-etnográfico y la confianza en los resultados se evaluó mediante GRADE CERQual. Los resultados de los estudios cuantitativos se sintetizaron narrativamente y se evaluaron mediante una adaptación de CERQual. Los resultados de la revisión cualitativa y cuantitativa se triangularon utilizando una matriz de codificación de convergencia.

Resultados

Se incluyeron 42 estudios (publicados entre 1985 y 2019): seis cualitativos, uno mixto y 35 cuantitativos. Treinta y cinco procedían de países de altos ingresos y siete de entornos pertenecientes a países de ingresos bajos y medios. La confianza en los resultados fue moderada o baja. El parto vaginal espontáneo era el que tendía a estar más asociado con resultados positivos a corto y largo plazo, y la cesárea de emergencia la que menos lo estaba. Las opiniones y experiencias del parto vaginal asistido se encontraban en un lugar intermedio entre los anteriores. El parto vaginal asistido, cuando está indicado, puede ser una alternativa efectiva y aceptable a la cesárea. Los estudios y encuestas de índole cualitativa convinieron, total o parcialmente, en que la experiencia del parto vaginal asistido se ve afectada por el carácter inesperado de los acontecimientos y, especialmente en entornos de altos ingresos, por las expectativas no satisfechas. Las relaciones positivas, la buena comunicación, la participación en la toma de decisiones y (creer en) el motivo de la intervención fueron mediadores importantes en la experiencia del parto. Las actitudes y habilidades profesionales fueron al mismo tiempo obstáculos y facilitadores del parto vaginal asistido en estudios cuantitativos.

Conclusiones

La información, la interacción positiva y la comunicación con los proveedores, así como la atención respetuosa, son facilitadores para la aceptación del parto vaginal asistido. Los obstáculos incluyen la falta de capacitación y de habilidades para la toma de decisiones y para el uso de los instrumentos.

Resumo

Contexto

Quando surgem algumas complicações no segundo período do trabalho de parto, o parto vaginal instrumental (PVI), a fórcipe ou com vácuo extrator, pode melhorar os desfechos. Isso se dá porque o PVI pode encurtar o trabalho de parto prolongado ou acelerar o parto no caso de complicações maternas ou fetais. Nas últimas décadas, o uso do PVI tem diminuído em muitos locais devido à preferência pela cesariana (CS). O objetivo desta revisão foi ampliar o conhecimento sobre as experiências, as barreiras, e os facilitadores para o uso do PVI.

Métodos

Fizemos uma busca sistematizada em oito bases de dados usando palavras pré-definidas para identificar estudos com dados sobre as opiniões e experiências de usuárias de maternidades, seus parceiros, profissionais de saúde, formuladores de políticas, e financiadores sobre o PVI. Avaliamos a qualidade metodológica dos estudos incluídos. Usamos a abordagem meta-etnográfica para fazer uma síntese dos achados qualitativos. Usamos o GRADE CERQual para avaliar a confiança nos resultados da revisão. Usamos uma adaptação do GRADE CERQual para sintetizar os resultados dos estudos quantitativos. Triangulamos os resultados qualitativos e quantitativos da revisão usando uma matriz de convergência dos modos de codificação.

Resultados

Incluímos 42 estudos (publicados entre 1985–2019): seis qualitativos, um estudo com métodos mistos e 35 estudos quantitativos. Trinta e cinco estudos eram de países de alta renda e sete eram de países de baixa ou média renda. A confiança nos resultados foi moderada ou baixa. O parto vaginal espontâneo foi a via de parto com maior probabilidade de desfechos positivos no curto e no longo prazo enquanto a CS de emergência foi a via com menor probabilidade desses desfechos. As opiniões e experiências relacionadas ao PVI ficaram entre esses dois extremos. Quando indicado, o PVI pode ser uma alternativa eficaz e aceitável à cesariana. Nos estudos e inquéritos qualitativos, houve concordância total ou parcial que a experiência do PVI é afetada pela natureza inesperada dos eventos e por expectativas frustradas, especialmente nos países de alta renda. Relações positivas, uma boa comunicação, o envolvimento na tomada de decisões, e acreditar na indicação do procedimento foram importantes mediadores da experiência do parto. Nos estudos quantitativos, a atitude e a competência dos profissionais (desenvolvimento) foram tanto barreiras como facilitadores para o PVI.

Conclusões

Informações, interações e comunicação positivas com os profissionais de saúde, e uma assistência respeitosa são facilitadores para a aceitação do PVI. As barreiras incluem a falta de treinamento e competência para a tomada de decisões, além do uso de instrumentos.

Similar content being viewed by others

Plain English summary

Assisted vaginal delivery (AVD) is a vaginal birth where an instrument, usually forceps or vacuum extractor, is used to help the birth if complications arise during the second stage of labour. In many countries, AVD has become less commonly used and rates of caesarean section (CS) have risen. While CS can be life-saving for mother or baby, it is sometimes used where there is no medical need, which has risks. It is possible that AVD could be used in some situations instead of unnecessary CS. AVD is safe when used properly but has risks if used inappropriately or by unskilled people. Our aim in this review was to explore parents’ and healthcare providers’ views and experiences of AVD to understand what might support or prevent its use. We reviewed 42 studies (published 1985–2019), 35 from high-income countries, and seven from low and middle-income countries. We rated the confidence in the findings as moderate or low. We found that spontaneous vaginal birth was more likely to be associated with positive outcomes, followed by elective CS, and where women needed interventions, outcomes and experiences were generally better for AVD than for emergency CS. Where indicated, AVD can be an effective, acceptable alternative to caesarean section. Parents’ experience of AVD is improved by positive relationships, good communication, being involved in making decisions, and believing in the reason for AVD. Professionals’ attitudes and skills influence the use of AVD.

Background

Assisted Vaginal Delivery (AVD) is a vaginal birth with the help of an instrument, usually forceps or vacuum. It is commonly performed for complications such as actual or imminent fetal compromise, to shorten the second stage of labour for maternal benefit, or for prolonged second stage of labour, especially where the fetal head is malrotated. AVD has the potential to improve maternal and newborn health and outcomes in any setting where the maternal and fetal condition require the rapid birth of the baby, and where it can be done safely. This may be particularly valuable in settings where caesarean section is not available, and where, even if available, surgical safety or safe management of complications cannot be guaranteed [1,2,3]. This is a particular issue when the woman is late in labour and the fetal head is very low in the pelvis.

Overuse of caesarean section has been a growing global concern during the last decades [4]. In 1985, the World Health Organization (WHO) stated that there was “no justification for any region to have a caesarean section rate higher than 10-15%” [5]. This was based on the scarce evidence available at that time. Since then, the rates of caesarean section have increased steadily in both HIC and LMIC countries [6]. This trend has not been accompanied by significant maternal or perinatal benefits; on the contrary, there is evidence that beyond a certain threshold, increasing caesarean section rates may be associated with increased maternal and perinatal morbidity. In low income settings particularly, the intrinsic risks associated with a surgical procedure such caesarean section also leave women and babies in a more vulnerable situation [1, 2, 7, 8]. In 2015, the WHO released a new Statement on Caesarean Section rates which superseded the earlier 1985 Statement emphasizing that “At population level, caesarean section rates higher than 10% are not associated with reductions in maternal and newborn mortality rates” and that “every effort should be made to provide caesarean sections to women in need, rather than striving to achieve a specific rate” [9, 10]. In October 2018, a new WHO guideline was released: WHO recommendations on non-clinical interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections. Although the available evidence is limited, WHO includes recommendations on education and support for expectant mothers, implementation of clinical guidelines, audit and feedback, mandatory second opinion before conducting a caesarean section, models of childbirth care and financial disincentives for doctors and systems [11].

Although forceps and vacuum are not inherently dangerous, inappropriate decision making about when to use them, or sub-standard level of technical skills or training can cause iatrogenic harm, and this could disincentivize their use in favour of a caesarean section (if this is possible and a safe option locally) or even be a barrier to their use where they are the only technical solution available [2, 3]. The practice of AVD is more prevalent in high-income countries than in low- and middle-income settings [12]. A recent study of AVD use in 40 low- and middle-income countries found the most common reasons for not performing AVD were lack of equipment, lack of sufficiently trained staff, and national and institutional policies [12]. Other barriers may include misplaced perceptions that risk of mother to child HIV transmission is increased with use of AVD [3].

Given the potential benefits of AVD in terms of improving maternal and newborn health and outcomes and reducing caesarean section use, we aimed in this review to improve understanding of the limitations, barriers and potential facilitating factors for the appropriate use of AVD, from the point of view of women, service providers, policy makers, and funders. We therefore asked the following questions:

-

1.

What views, beliefs, concerns and experiences have been reported in relation to AVD?

-

2.

What are the influencing factors (barriers) associated with low use of/acceptance of AVD?

-

3.

What are the enabling factors associated with increased appropriate use of/acceptance of AVD?

Methods

A protocol for the review was published in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews [13] prior to completion of the searches. We used a systematic sequential mixed-methods design [14]. The review was carried out according to the protocol with the following exceptions: no subgroup analyses were carried out due to insufficient data, and we decided by consensus to include PhD theses if they met the inclusion criteria and the data were not also reported in an associated publication.

Criteria for study inclusion

Our focus was on the views, beliefs and experiences of maternity service users (including birth companions), health care providers, policy makers and funders regarding the acceptability, applicability and safety of, and knowledge and confidence in, AVD, which facilitate or inhibit its appropriate use. We included studies with qualitative designs (e.g. ethnography, phenomenology) or qualitative methods for data collection (e.g. focus group interviews, individual interviews, observation, diaries, oral histories), and studies using quantitative surveys and audits. There were no language restrictions. Studies from any country were eligible for inclusion; we defined low- and middle-income countries according to the OECD’s list of official development assistance recipients effective as at 1 January 2018. We limited our searches to studies published on or after 1985, the year of the first WHO statement on optimal caesarean section rates. Studies whose principal focus was breech presentation, multiple pregnancies, or those who have experienced a transverse or oblique lie or preterm birth were not included.

Reflexive note

The authors varied in disciplinary backgrounds and experiences that may have influenced their input. In accordance with good practice in qualitative research [15] we considered our biases throughout the process and conferred regularly to reduce the impact on our findings. NC is health researcher whose research on breastfeeding and the postnatal period has informed her views on the importance of understanding and respecting women’s views and needs throughout the perinatal period. CK is a medical sociologist who held prior beliefs about mode of birth informed by interviews with women who have experienced primary assisted and spontaneous vaginal birth, planned and unplanned caesarean birth. MCB is a qualitative health researcher whose background has led her to focus on women’s voices in medical discourses. APB is a medical officer with over 15 years of experience in maternal and perinatal health research and public health. SD is a Professor of Midwifery; her interactions with the data were informed by her experience of supporting childbearing women as they experienced AVD. This included both brutal and disrespectful and sometimes unnecessary AVD that left women devastated, and careful, respectful AVD that left them joyful and positive. She strongly believes that respect for the physiology of birth and for women’s values and beliefs is the basis for understanding when and how to undertake AVD, and when and how to discuss this option with labouring women and partners.

Search strategy

Systematic searches were carried out in April 2019 in CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, Global Index Medicus, POPLINE, African Journals Online and LILACS. Searches were carried out using keywords for the Population, Intervention, and Outcomes where possible, or for smaller databases, using intervention keywords only. An example search strategy is shown in Additional File 1. In addition to systematic searches of electronic databases, we searched the reference lists of all included studies and the key references (i.e. relevant systematic reviews), both back chaining and forward checking for any references not identified in the electronic searches which may also be relevant. The following grey literature databases were searched: Open Grey, Open access thesis & dissertations, and Ethos.

Study selection

Records were collated into Covidence systematic review software [16] and duplicates removed. Each abstract was independently assessed against the a priori inclusion/exclusion criteria by two review authors and irrelevant records discarded. Full texts of remaining papers were independently assessed by two review authors for eligibility, discrepancies adjudicated by a third reviewer, and the final list of included studies agreed among the reviewers.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Study characteristics (details of the study, authors, study design, methods, intervention(s), population and results) were collected on a data extraction form. Quality of quantitative studies using a survey design was assessed using a critical appraisal checklist for a questionnaire study [17, 18], after which studies were graded A–D by discussion between two authors based on the outcome of the checklist. Quality of qualitative studies was assessed using the criteria from Walsh & Downe [19] and the A–D grading of Downe [20]. Initially, a pilot quality assessment of three studies was carried out by two authors independently to assess feasibility of the quality assessment tools. Then the studies were assessed by one, and checked by a second, review author. Disagreements were resolved through discussion, or by consulting a third review author.

Data synthesis

Qualitative data was analysed using the principles of meta-ethnography [21]. The approach was comprised of five stages 1) Familiarisation and quality assessment; 2) Data extraction; 3) Coding; 4) Interpretative synthesis; and 5) CERQual assessment [22]. Two review authors (NC, CK), undertook coding and interpretive synthesis, with consensus reached in discussion with a third author (MCB). Starting with the earliest published paper [23], review authors read each study in detail, and independently extracted the results reported by the study authors, including any relevant verbatim quotes, along with the themes/theories/metaphors. Codes were constructed from the extracted data from the index paper and compared with data from each of the other papers until all the data had been coded into initial concepts. Data could be coded to more than one initial concept if this seemed appropriate. Initial concepts were discussed, refined and agreed by consensus before being coalesced into emergent themes. Themes were constructed by comparing similarities between the studies already analysed, and the one currently under review (‘reciprocal analysis’), and by looking for what might be different between the previous analysis and the paper currently under review (‘refutational analysis’). The emergent themes comprised the review findings. These were grouped into final themes and the resultant thematic structure was synthesised into a line of argument synthesis [21]. Degree of confidence which can be placed in each review finding was then assessed using the GRADE CERQual approach [22], in which each finding was assessed having either minor, moderate, or substantial concerns with respect to each of four domains: 1. methodological limitations of included studies; 2. relevance of the included studies to the review question; 3. coherence of the review finding; and 4. adequacy of the data contributing to a review finding. Then, based on an overall assessment of these four domains, confidence in the evidence for each review finding was assessed as high, moderate, low or very low.

Narrative synthesis of quantitative data from surveys and questionnaires was undertaken by two authors (SD, CK independently, with final decisions by consensus) [24]. Textual descriptions of individual studies were sub-grouped according to participants and factors of interest. Narrative summaries were then produced and organised thematically. There is currently no quantitative equivalent of CERQual for narrative summaries of survey data, but we agreed within our team that CERQual principles are transferable. We therefore applied CERQual criteria to the narrative summaries emerging from the survey and audit data. Finally, quantitative and qualitative data syntheses were combined using a ‘convergence coding matrix’. This approach illustrates the extent of agreement, partial agreement, silence, or dissonance between findings from included quantitative and qualitative studies [25]. The term agreement means that codes from more than one data set agree; partial agreement refers to agreement between some but not all data sets; silence refers to codes that are found in one data set but not others; and dissonance refers to disagreement between data sets, in meaning or salience.

Results

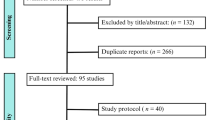

From the searches, 1387 studies were identified, and a further five studies [23, 26,27,28,29] were identified from other sources. After 243 duplicates were removed, 1035 records were discarded as irrelevant after reviewing title and abstract. Of 107 full text papers screened, 65 records were excluded. This left 42 studies for quality assessment and synthesis [12, 23, 26, 28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66]. The earliest included studies were from 1985 [43, 45, 46] and the most recent from 2019 [29]. Figure 1 PRISMA Diagram illustrates the study selection process.

Six studies were qualitative studies of maternity service users reporting the views and experiences of 73 women and 20 men from three high-income countries (Sweden, UK, USA) [23, 26, 30,31,32,33]. The earliest study included in the qualitative evidence synthesis was from 2003 [23] and the most recent from 2015 [31]. It was not possible to conduct a qualitative evidence synthesis of provider data since only one (mixed-methods) study with qualitative data from healthcare providers was identified [34]. Four included survey studies [29, 36, 50, 66] reported some free-text responses. These papers, along with the six included qualitative studies [23, 26, 30,31,32,33] and the mixed-methods study [34] provided the starting point for our convergence coding matrix. In total 36 studies were included in the quantitative narrative synthesis, of which seven were from LMIC settings.

Table 1 gives an overview of the characteristics and quality assessment of all included studies. Thirty-five studies were from high-income countries, one from an upper-middle-income country, one from a lower middle-income country and three from least developed countries according to the OECD’s DAC list of Official Development Assistance Recipients 2018–2020. One study was a multi-country study of 40 LMICs and another was a multi-country survey. Thirty-one studies were rated A or B, and 11 rated C on quality assessment. No studies were excluded on grounds of quality. Fifteen of the 42 studies (36%) did not differentiate between forceps and ventouse, and of the quantitative surveys, in 33% (12/42), women and/or partners were asked about their experiences of AVD while on the postnatal ward [37, 38, 43, 44, 48, 49, 51, 52, 55, 56, 58, 61].

From 36 included studies with quantitative data [12, 28, 29, 34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66], we derived eight narrative summaries, which we grouped into four thematic headings: prevalence of AVD use in practice; skills and attitudes (including professional and personal attitudes of healthcare professionals); experiences of the birth; and impact and consequences of AVD for women and partners. Table 2 shows the summary of quantitative review findings and associated confidence assessments. From the six included qualitative studies, [23, 26, 30,31,32,33], we derived 10 review findings, which mapped to four distinct final themes: ‘coming to know AVD by experience’, ‘turbulent feelings about the actual experience’, ‘trust, control, and relationships’, and ‘implications for future reproductive choices’. A summary of the initial concepts, emergent themes and final themes is shown in Table 3, while Table 4 shows the summary of review findings and associated CERQual assessment. Inevitable differences were apparent between the in-depth views and experiences framing of the qualitative studies and the structured preferences, opinions and outcomes framing of most of the quantitative studies. There was, however, agreement or partial agreement, evident across study designs, that the impact of unmet expectations/of unexpected events, good communication, and (believing in) the reason for intervention are all critical mediators of how actual birth experiences are perceived by women. Table 5 Convergence coding matrix shows triangulation of the qualitative and quantitative evidence synthesis and provides the structure for the reporting of findings hereafter. Summary of findings statements are highlighted in bold.

What views, beliefs, concerns and experiences have been reported in relation to AVD?

Women’s experiences of assisted vaginal delivery (Table 2) were reported in 16 surveys [28, 29, 36, 43, 44, 46,47,48, 51, 53, 56, 58, 60,61,62,63]. Only one of these was from a LMIC country (Uganda) [29]. In these surveys, having an unplanned mode of birth, emergency CS or AVD (and especially where the intervention is done for delay in labour rather than for acute clinical risk) seemed to be associated with less positive reports of childbirth experience for women. A better experience was reported after ventouse than forceps in most, but not all comparisons. Instrumental birth with episiotomy was the most distressing, especially after trial of labour following previous CS. Further detail as to why and how the unplanned nature of AVD impacts on women’s experiences was evident in the theme Coming to know AVD by experience (Table 4). The emergent theme A birth you couldn’t plan for encapsulates postnatal mothers’ and fathers’ concerns (in HICs) relating to Expectations and preparedness for AVD [23, 26]. In part, this was because AVD had simply not been contemplated beforehand or did not fit into women’s ideas of what birth would be like: “I sort of missed out the forceps and ventouse, in my mind I’d sort of thought it was going to be a natural delivery or caesarean, so I hadn’t really considered forceps or ventouse” [23]. In addition to views of feeling unprepared, the belief that AVD could not be prepared for was also evident. Some participants felt disillusioned because of the disparity between their birth plans and what happened. In two UK studies there were views that AVD was not adequately explained in antenatal education. Other women, however, described deliberately avoiding consideration of the possibility, in order to manage their own feelings about birth: reading too much information was believed to provoke anxiety. Women and men in two UK studies described ‘keeping an open mind’: believing that, with regard to birth, “There are so many variables that no one can predict” [26]. In the same two qualitative studies [23, 26], both from the UK, mothers’ and fathers’ Beliefs about need/indications influenced their acceptance of the procedure: “Surprisingly to me I was quite happy to go along with the doctor’s call. I normally would question why and how but at the time it seemed like an emergency” [26]. However, findings from these two studies also suggested there could be lack of understanding about why an AVD had been performed. Some women expressed beliefs that there had been problems with their baby that necessitated AVD, while others described being unable to recall why they had had an AVD. Reconciling/coping with experience emerged as a theme in one study from the UK [26]. Finding a context for their birth experiences, believing it to be necessary for the baby or seeing the baby’s wellbeing as a ‘priority’, allowed women to come to terms with their birth experience, while other women were unable to reconcile.

Fourteen surveys contributed to the quantitative narrative review finding reporting the Impact of assisted vaginal delivery (women) (Table 2) [2, 28, 29, 36, 38, 40, 42,43,44, 54, 55, 58, 61, 63]. Studies have variously measured postnatal mood, sexual function, desire to have more children, dyspareunia, postnatal fear of childbirth, pain, haemorrhoids, backache. Unsurprisingly, having an emergency CS or an AVD appeared to be associated with less positive outcomes than having a spontaneous vaginal birth or an elective CS. Having a spontaneous vaginal birth without instruments or episiotomy seemed to result in the most positive outcomes in the short and longer term for most variables. In some studies, emergency CS was associated with least positive impacts, followed by assisted vaginal birth (negative outcomes reported for both forceps or ventouse in some studies – others show better outcomes for ventouse than CS in the short and longer term). In others, instrumental birth was the most distressing. Surveys that assessed preference for mode of birth next time indicate that spontaneous vaginal delivery is preferred by most, with some preferring planned CS. If instrumental birth is required, most seemed to prefer ventouse over forceps. For partners the experience of witnessing assisted vaginal delivery (Table 2), resulted in a few stating that they wouldn’t have more children, and some would prefer their partner chose elective CS next time [28, 37, 38]. There was agreement between this finding and the qualitative emergent theme Mixed views about any future pregnancy and delivery (Table 4) and the reasons for future preferences [23, 26, 31]. After the experience of AVD, some women were put off a future pregnancy, even if they perhaps would have wished for more children: “I would like another baby but that is there at the back of my mind thinking oh could I really go through all that again” [23]. Others wished to avoid the possibility of enduring AVD again by electing to have a caesarean section: “I don’t want to have to go through all of that again ... I just wanna have one slice in the belly and whoosh!” [23]. However, other women expressed the wish for vaginal birth if they were to become pregnant again, with some suggesting they would be more confident next time as they would feel prepared: “If I have to have that with another baby it won’t ever be as worrying because I know exactly what to expect” [23].

What are the influencing factors (barriers) associated with low use of/acceptance of AVD?

Twelve surveys, three from LMICs [12, 41, 66] and nine from HICs [39, 45, 46, 50, 54, 55, 58, 61, 64] report prevalence rates by unit or by practitioners. At each time period, and where studies include a range of sites, Prevalence of assisted vaginal delivery (Table 2) varied widely. Lack of equipment and lack of trained staff were the prominent concerns perceived to contribute to low prevalence and early default to caesarean section. Reluctance to use AVD for some practitioners in one UK study was associated with insufficient pain relief for women, the presence of significant fetal caput, or lack of enough experience to become skilled [50]. In general, practitioners in more recent studies seem to be more positive about using the ventouse than about using forceps. One study investigating midwife ventouse practitioners in the UK noted that they were generally confident following their training in this technique, and that their extensive experience of spontaneous deliveries gave them confidence in, sometimes, not performing a ventouse when called, subsequent to estimating that the baby could safely be born spontaneously [34].

There were mixed findings about self-reported Skills (development) in assisted vaginal delivery of obstetricians in determining the need for, seeking a second opinion in, and accuracy of clinical skills for, instrumental delivery (Table 2) [39, 41, 43, 50, 57, 64]. Midwives who were trained in using ventouse in the UK seemed to be confident in its use [34]. Actual skills and competence were not tested in any included studies. The results of one relatively recent UK study [50] include professional views on use of ultrasound to assess fetal position prior to conducting AVD, showing 1:5 have used it, but including strong views that it should not become a replacement for clinical assessment skills. Professional attitudes to the use of assisted vaginal delivery varied by country, training programme, and seniority (Table 2) [39, 41, 45, 57, 59, 64]. In two UK surveys reporting the Personal attitudes to mode of birth for oneself/partner (obstetricians) the majority of respondents were happy to have an assisted vaginal birth, as an alternative to caesarean section for mid-cavity arrest, especially if they could choose the operator (Table 2) [35, 65]. As shown in Table 5 Convergence coding matrix, data relating to the use of AVD, health professionals’ skills, professional attitudes and personal attitudes, were not reported in any of the qualitative studies.

There was some evidence of the factors that influence women’s acceptance of the procedure in the qualitative theme turbulent feelings about the actual experience (Table 4), which describes the powerful and contrasting feelings women and men experience in relation to AVD. In five qualitative studies, from three countries (all HICs), women and men used strong imagery to convey their Frightening and violent experiences of AVD [26, 30,31,32,33]. Women were distressed when the procedure was carried out in a way they experienced as lacking care or compassion: “The doctor came in and just basically ripped her out with forceps, it’s just like extracted her from my body. I really think part of it was the position ... all these people in there and the total lack of... that there was a human being on the table [ crying] going through this” [33]. Men and women were also distressed by the perception of AVD as a violent experience for the baby: there were fears about injury to the baby, and feelings of shock at the forcefulness of the procedure: “I honestly expected to see the baby’s head dangling from the end [-] sounds horrible but that’s the amount of force and then the noise of the pop and then seeing the doctor hit the wall and then the mess that followed it was something out of a horror film” [26]. Some women reported experiences of detachment or dissociation, being physically present but mentally absent: “Actually, I was totally gone, I know there are tons of people in the room and they asked me simple stuff but I couldn’t even answer” [30]. In three surveys (all HICs) the Experience of witnessing assisted vaginal delivery (partners) seemed to be associated with less positive reports of childbirth for partners than spontaneous vaginal birth (Table 2) [28, 37, 38].

In the 16 surveys of Women’s experiences of assisted vaginal delivery, a few studies reported that negative experience of AVD is associated with poor pain relief (Table 2) [28, 29, 36, 43, 44, 46,47,48, 51, 53, 56, 58, 60,61,62,63]. However, in one study women with spontaneous birth compared to AVD reported more problems with postpartum pain, and intrapartum pain management [58]. Contradictory views about Pain was also an emergent theme from four qualitative studies (all from HIC; Table 4) [26, 30,31,32]. For some women, effective pain relief enabled them to feel ‘relaxed’ about the prospect of AVD, while others described feeling supported to manage pain: “They really listened to how I felt and how I wanted things when I was in pain and everything” [30]. However, for some women, the pain was a traumatic experience “When they were going to put in the vacuum extractor it was without doubt the worst thing I’ve ever been through; it was the worst thing I’ve ever done because it hurt so unbelievably much. So that I screamed right out, No way! Help, help, I’m dying.”[screams] [32].

Also encompassed in the qualitative theme turbulent feelings about the actual experience were Positive or beneficial reactions to AVD expressed by women and men (Table 4) [26, 31, 32]. These views were evident in three studies, from two countries (both HIC), and conveyed feelings of relief that labour was over and that the baby had been born safely: “Relief of an end to labour When it [the vacuum extractor] was attached, it was no problem and when she [the baby] came, everything was over and it just felt good” [32]. Some women and men in one study reported simply feeling unperturbed: the process was as they had anticipated and they were not troubled by it. Some men in two studies from two countries described feelings of joy at the arrival of the new baby: “I was really touched. That was one of the greatest moments in my life” [31]. Also from these two studies, some men saw it as their role to provide emotional strength to support their partners, to stay ‘calm’ so that their partners did not panic, or to help relay information from healthcare providers. While some felt unable to give as much support in the way they wished, others described coping with their own anxiety so that they could help.

What are the enabling factors associated with increased appropriate use of/acceptance of AVD?

Six surveys (five HICs [36, 43, 50, 52, 61], 1 LMICs [41]) reported the importance of Communication, information and consent (Table 2) to women’s perceptions of their experience of AVD, with some evidence that many women do not have information about the risks and benefits of AVD (plus or minus episiotomy), either antenatally, intrapartum when the procedure is used, or postnatally to explain what happened. There was partial agreement between this quantitative finding and the qualitative theme Trust, control and relationships, which suggests that acceptance of AVD is facilitated by positive interactions with staff, respectful care, ongoing communication and trust in care providers when women’s control over birth is lost, while negative interactions with staff, poor communication, little involvement in decision-making and mistrust of caregiver is a barrier to acceptance (Table 4).

In three studies from two HICs, both women and men expressed a wish to be part of a team with healthcare providers describing how they welcomed Active participation through collaboration and involvement (Table 4) [26, 30, 31]. Healthcare providers could facilitate a collaborative approach both through their interactions “She touched my belly and kind of helped me, now I think it feels like a contraction and now it’s time to push” [30] and by involving women and men in decision-making. Men in one study expressed a wish to be included, and could feel excluded or that their experience was not recognised: “OK you maybe not pushing the baby out but you are certainly going through the same if you take the physical aspect out going through the same emotions.” [26]. Balancing control and trust between women, fathers and health professionals was reported to be important in five of six qualitative studies (Table 4) [26, 30,31,32,33]. In five studies from three countries women described feeling loss of control; this was experienced as challenging. Loss of control could be experienced as loss of physical control, or as lack of agency, with some women recalling feelings of hopelessness. A trusting relationship with healthcare providers enabled women to accept AVD and manage feeling out of control. “People listening to what I said and acknowledging what it was like for me being kind made it easier for me to say right ok [-] completely trusted certainly the two midwives who were in the delivery room.” [26]. Some men in one study described an erosion of trust as they began to feel communication from healthcare providers was not honest. “We felt both of us after a while that it almost went to an extreme; when she started pushing and said like ‘wow’ almost after every contraction. They did not say that this would take a long time or a vacuum extraction would be needed, although they perhaps saw it... Finally you do not trust them so much” [31].

The need to understand and to be understood was also an emergent theme that contributed to acceptance of AVD (Table 4) [26, 30, 31]. Participants in three studies from two countries talked about the importance of feeling heard and understood, and having their wishes taken into account: “they listened so much and took things at my pace, so wait a little, I decided everything, they helped and gave me advice. It wasn’t as if they do this every day, it was as though I had to teach them. They really listened to how I felt and how I wanted things when I was in pain and everything” [30]. Women valued acknowledgement of how they were feeling. Good communication was seen as reciprocal: in one study women emphasised the importance of explanations and information to facilitate involvement. Communication was described as an embodied process, with participants explaining how healthcare providers made eye contact with them or touched them.

As already stated, there were no qualitative studies to compare with quantitative findings reporting prevalence of AVD use in practice or skills and attitudes of staff (Table 5). However, the silences, agreement, and dissonances between quantitative data from different resource settings, are of note. In agreement with the studies from HICs, one study of obstetricians’ views in Egypt found significant differences (< 0.05) intheir acceptance of instrumental delivery based on professional level of seniority. Consultants’ attitudes were more favourable to AVD than specialists or registrars [59]. There was dissonance between studies from HICs and LMICs as to why AVD use may have declined. Some participants in HICs referred to changing obstetric fashions, whereas a study from Tanzania disputed the suggestion that vacuum extraction is not modern obstetrics, with the claim that the high incidence of HIV/AIDS could be the primary barrier [66]. In both HIC and LMIC settings, there was evidence of midwives performing AVD [12, 34]. Ugandan women in one study [29] reported similar views to women participants in HICs [26, 31, 32] in terms of turbulent feelings about the actual experience and mixed views about any future pregnancy and delivery. In addition, women in Uganda voiced concerns about the likelihood of their death and death of their baby associated with caesarean section, and with the financial cost of the operation. These concerns meant that assisted vaginal delivery was preferable.

Discussion

Our mixed methods review identified only six qualitative studies of women’s views of AVD, and only one mixed-method study with qualitative data on provider views. We identified no studies of this design in low and middle-income countries. We included 36 studies in a quantitative narrative synthesis. Thirty-six percent of the studies did not differentiate between forceps and ventouse. In studies where the type of instrument was differentiated, there tended to be differences, usually (but not always) in favour of the ventouse. This suggests that future studies of mode of birth should always record which instrument was used, as not doing so limits understanding about what might work in particular circumstances, for particular women and practitioners. In quantitative surveys, in 33% of cases, women were asked about their experiences while still on the postnatal ward. In the study by Nolens et al. [29] in Uganda, women’s views about mode of birth did not change between 1 day and 6 months postnatally. However, other studies suggest that women tend to rate their experiences of labour and birth more positively as the postnatal period progresses [67] except for women who had extreme pain during labour and an epidural, many of whom continue to recall their birth negatively over time [68]. There is some evidence that this change in perception may be less positive for certain modes of birth, and notably CS with general analgesia [67]. These findings suggest that studies of women’s views of different modes of birth during the very early postnatal period may not be representative of their views and choices later. This may have particular resonance if women’s early views and experiences are seen as a proxy for preferred mode of birth for subsequent pregnancies.

Where outcomes were assessed by mode of birth in longitudinal surveys, spontaneous vaginal birth almost always resulted in lower levels of longer term physical and psychological harms, and more positive birth experience and self-esteem ratings from women. Planned caesarean section also tended to score relatively well on these measures. Women tended to report the most negative scores when they had had an emergency CS. On most measures assessed in the studies assessing various experience measures, women who had AVD were usually more positive than those who had an emergency CS, but less so than those who had either spontaneous vaginal birth or planned CS. This finding is unsurprising, as the reasons for using an instrument to assist birth or conduct an emergency CS would, by themselves, be a source of anxiety and affect women’s experiences. There is also a need to go beyond intrinsic aspects of AVD or CS, because the experience of (a trial of) ventouse, forceps and emergency CS are not mutually exclusive. In fact, the key and consistent insight emerging from the triangulation between qualitative and quantitative evidence women and their partners was the shock of the unexpected nature of events, the inherently unpredictable experience of birth by AVD (and, indeed, by emergency CS), and, particularly in high-income settings, the unmet expectations.

Respectful and relational factors that might mitigate this shock, and limit any consequent distress and adverse sequelae, also emerged strongly from both data sets. This review suggests that positive relationships, good communication, involvement in decision-making, and, for women and partners, (believing in) the reason for intervention were important mediators of birth experience, and thus may be of considerable value to alleviate emotional distress when complications arise that require an AVD or emergency CS. These findings resonate strongly with the growing literature on positive childbirth experiences [69] and on the value of respectful, kind, compassionate maternity care in general [70]. For both parents, it seems the distress of unexpected interventions associated with AVD (including episiotomy, need for unplanned pain relief, such as epidural analgesia, and concern for possible iatrogenic harm to the baby of using instruments) may be mitigated by how health professionals communicate, both at the time of decision-making, and during the process. Underlying expectations can also influence interpretation of the AVD experience. In our qualitative findings from HICs, it was apparent that women’s expectations and birth plans did not always anticipate the unpredictable nature of birth. This finding cannot be generalised to LMICs where women’s expectations of birth are different. In LMICs, in some contexts, AVD was preferred over CS due to fear of death of mother or baby subsequent to a surgical procedure, but this preference was less pronounced in HICs. Some survey data indicated highly negative experiences for partners, but most of the qualitative studies that included partners reported a more even mix of negative and positive accounts.

Prevalence data suggest that the use of AVD was much more common (and that experience with it was therefore much more mainstream) prior to 2000 than in the last decade or so. This was true for both high and low income settings. However there is variation between settings, with ventouse is still used regularly in some European countries. Professional attitudes and skills (existing skills, or the development of skills de novo) were simultaneously barriers and facilitators of AVD in quantitative studies. Our findings are consonant with other studies focussing on provider competencies. A 2015 study evaluated the impact of a 2-day training course called Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics (ALSO), designed to increase care providers’ capabilities in managing obstetric emergences, in four low-income countries [71]. After training, rates of vacuum deliveries increased in hospitals in the two countries where this was evaluated (Honduras and Tanzania). Two studies excluded after full text screening [72, 73] addressed issues of skills, both in high-income settings. The UK-based study by Bahl and colleagues used interviews and video recordings of expert midwives and obstetricians to understand non-technical skills involved in an AVD and identified seven main categories (situational awareness, decision making, task management, team work and communication, relationship with the woman, maintaining professional behaviour, and cross monitoring of performance) [72]. Simpson and colleagues in Canada used videos of expert clinicians performing simulated forceps deliveries to identify verbal and non-verbal components of performing a safe delivery [73]. Building skills by training and preparing providers in adequate decision-making for instrumental vaginal delivery is fundamental to increase the use safely and appropriately. However, the most effective modality, duration and frequency warrants further research [74,75,76]. After our analysis was complete, we identified two surveys, both from HICs (UK and Australia), of trainee obstetricians’ views on using Kielland’s forceps [77, 78], and a study by Bahl and colleagues from the UK [79] on decision making in instrumental delivery, which we would have included in our analysis had we identified them at the search stage. Bahl et al. used qualitative data to identify a sequence of decision points used by expert obstetricians in proceeding to an instrumental birth [79]. Both surveys of trainees found that low numbers of trainees had seen a forceps delivery [77, 78]. In the UK study, a majority of trainees said they would use forceps if trained, and expressed a wish to undertake training [77], while very few trainees in the Australian study expressed an intention to use forceps as a consultant [78]. These additional papers would not have altered our findings. However given our findings highlighting the importance of training, we are undertaking a systematic review of the limitations, barriers and potential facilitating factors relating to expertise, training and competencies in AVD.

The use of a systematic approach to evidence synthesis and the GRADE-CERqual tool for the summaries of findings from both qualitative and quantitative studies has ensured the robustness and applicability of our findings. Few qualitative studies were identified, and they were only from high income countries. This is an important limitation, as our qualitative findings alone cannot be assumed to reflect views and experiences of staff or parents in other settings, and the small number of studies and countries limits confidence in the review findings even within high income settings. However, a strength of this sequential mixed-methods review is that it combines evidence from both qualitative and quantitative studies. Previously, survey data has usually slipped through the inclusion net of both meta-analytic systematic reviews and qualitative evidence syntheses. The inclusion and systematic quality assessment and analysis of good quality surveys and audits in this review, and of the narrative findings emerging from them, is a methodological advance in this area. There are more data from quantitative surveys and audits, and more of these studies were based in LMIC settings. Thirteen studies reported on prevalence [12, 29, 39, 41, 45, 46, 50, 54, 64, 66], but two of them were undertaken before 2000, so they provide data for historical comparison rather than insights into current practice [45, 46]. Confidence in the findings statements was generally rated moderate (7/10 SoFs) for the qualitative papers, and moderate or low for the quantitative studies.

Going forward, it is important for researchers, guideline developers, policy makers to differentiate between ventouse, forceps, and spontaneous vaginal birth – these are often all referred to as “vaginal birth” despite being distinct clinically and experientially. It is also essential that we do not further dichotomise discussions about mode of birth (as either vaginal or caesarean), but conceive birth as a trajectory, educating women and families that AVD is an option during labour. How best to educate women without provoking anxiety remains an important research question. Attempts to increase the use of AVD to reduce unnecessary caesareans must be carefully grounded in an understanding of the local context, resources, practitioner skills and training, and the prior views and experiences of the local childbearing population. Training in the physiology, anatomy and mechanisms of straightforward birth, and the interaction of the mother/child dyad in labour, is critical to reduce poor decision making about the need for instrumental or surgical birth, and to improve understanding and techniques when AVD is required. Assessment of the impact of introducing AVD programmes into any setting (HIC or LMIC) should be undertaken with careful audit of the views, experiences, confidence and competence of staff at the outset, and again when they have built skills, experience and confidence. Training of midwives to undertake AVD warrants further research, as their skills and experience in managing uncomplicated vaginal births places them in an optimal position for appropriate decision-making and use of the instrument. Audit of views, experiences and outcomes of women, partners and birth companions should continue into the longer term, and not just be undertaken on the postnatal ward.

Conclusions

Views and experiences of AVD are complex and varied. Although reports of traumatising experiences are numerous, experiences and views on AVD are driven to some extent by anxiety and distress due to the unexpected nature of the event. Information, positive interaction and communication with providers, and respectful care are facilitators for acceptance of AVD. Barriers include lack of training and skills for decision-making and use of instruments. Expanding AVD use must be preceded by high quality training and skills development in the recognition of both the physiology and the pathology of labour progress and maternal/fetal wellbeing, as well as in the assessment for, and use of, AVD techniques to ensure minimum trauma for mother and baby. Local resources to enable safe use and optimum short and longer-term outcomes of AVD and accompanying procedures (such as episiotomy) are essential, both for childbearing women, and, where they are present, for their birth companions.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- AVD:

-

Assisted vaginal delivery

- CS:

-

Caesarean section

- HIC:

-

High income countries

- LMIC:

-

Low and middle income countries

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Sobhy S, Arroyo-Manzano D, Murugesu N, Karthikeyan G, Kumar V, Kaur I, Fernandez E, Gundabattula SR, Betran AP, Khan K, et al. Maternal and perinatal mortality and complications associated with caesarean section in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019;393:1973–82.

Nolens B, Capelle M, van Roosmalen J, Mola G, Byamugisha J, Lule J, Faye A, van den Akker T. Use of assisted vaginal birth to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections and improve maternal and perinatal outcomes. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e408–9.

Pattinson RC, Vannevel V, Barnard D, Baloyi S, Gebhardt GS, le Roux K, Moran N, Moodley J. Failure to perform assisted deliveries is resulting in an increased neonatal and maternal morbidity and mortality: An expert opinion. South Afr Med J. 2018;108(2):2018.

Boerma T, Ronsmans C, Melesse DY, Barros AJD, Barros FC, Juan L, Moller A-B, Say L, Hosseinpoor AR, Yi M, et al. Global epidemiology of use of and disparities in caesarean sections. Lancet. 2018;392:1341–8.

World Health Organization. Appropriate technology for birth. Lancet. 1985;326:436–7.

Betrán AP, Ye J, Moller A-B, Zhang J, Gülmezoglu AM, Torloni MR. The increasing trend in caesarean section rates: global, regional and National Estimates: 1990-2014. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0148343.

Bishop D, Dyer RA, Maswime S, Rodseth RN, van Dyk D, Kluyts H-L, Tumukunde JT, Madzimbamuto FD, Elkhogia AM, Ndonga AKN, et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes after caesarean delivery in the African surgical outcomes study: a 7-day prospective observational cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e513–22.

Fawcus S, Pattinson RC, Moodley J, Moran NF, Schoon MG, Mhlanga RE, Baloyi S, Bekker E, Gebhardt GS. Maternal deaths from bleeding associated with caesarean delivery: A national emergency. S Afr Med J. 2016;106(5):2016.

World Health Organization. WHO Statement on Caesarean Section Rates. WHO/RHR/15.02. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

Betrán AP, Torloni MR, Zhang JJ, Gülmezoglu AM. Section WHOWGoC: WHO Statement on caesarean section rates. BJOG. 2016;123:667–70.

Betrán AP, Temmerman M, Kingdon C, Mohiddin A, Opiyo N, Torloni MR, Zhang J, Musana O, Wanyonyi SZ, Gülmezoglu AM, Downe S. Interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections in healthy women and babies. Lancet. 2018;392:1358–68.

Bailey PE, Roosmalen J, Mola G, Evans C, Bernis L, Dao B, Bailey PE, van Roosmalen J, de Bernis L. Assisted vaginal delivery in low and middle income countries: an overview. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;124:1335–44.

Assisted Vaginal Delivery (AVD) to facilitate complicated deliveries and reduce unnecessary caesarean sections: a systematic review PROSPERO 2019 CRD42019134681. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php? ID=CRD42019134681.

Hong QN, Pluye P, Bujold M, Wassef M. Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Syst Rev. 2017;6:61.

C G, MA B, S D, EJ P, S L. (EPOC) oboEPaOoC: EPOC Qualitative Evidence Synthesis: Protocol and review template. EPOC Resources for review authors. Oslo: Norwegian Institute of Public Health; 2019.

Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation..

Critical appraisal checklist for a questionnaire study. British Medical Journal.https://www.bmj.com/content/suppl/2004/05/27/328.7451.1312.DC1. Accessed 4 June 2019.

Critical appraisal checklist for a questionnaire study. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg188/evidence/appendix-k-metholdogy-checklist-pdf-6958881110].

Walsh D, Downe S. Appraising the quality of qualitative research. Midwifery. 2006;22:108–19.

Downe S, Simpson L, Trafford K. Expert intrapartum maternity care: a meta-synthesis. J Adv Nurs. 2007;57:127–40.

Noblit GW, Hare RD, Hare RW, Van Maanen J. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. London: SAGE Publications; 1988.

Lewin S, Booth A, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Rashidian A, Wainwright M, Bohren MA, Tunçalp Ö, Colvin CJ, Garside R, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: introduction to the series. Implement Sci. 2018;13:2–2.

Murphy DJ, Pope C, Frost J, Liebling RE. Women’s views on the impact of operative delivery in the second stage of labour: qualitative interview study. BMJ (Clin Res ed). 2003;327:1132.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, Britten N, Roen K, Duffy S. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. Lancaster: In: ESRC Methods Programme. Lancaster: ESRC; 2006.

O’Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. BMJ. 2010;341:c4587.

Hurrell RA. Men and women s experiences of instrumental delivery: a qualitative study. Glasgow: University of Glasgow; 2006.

Geelhoed D, de Deus V, Sitoe M, Matsinhe O, Lampião Cardoso MI, Manjate CV, Pinto Matsena PI, Mosse Lazaro C. Improving emergency obstetric care and reversing the underutilisation of vacuum extraction: a qualitative study of implementation in Tete Province, Mozambique. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:266.

Hildingsson I, Karlström A, Nystedt A. Parents’ experiences of an instrumental vaginal birth findings from a regional survey in Sweden. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2013;4:3–8.

Nolens B, van den Akker T, Lule J, Twinomuhangi S, van Roosmalen J, Byamugisha J. Women’s recommendations: vacuum extraction or caesarean section for prolonged second stage of labour, a prospective cohort study in Uganda. Tropical Med Int Health. 2019;24:553–62.

Sjodin M, Radestad I, Zwedberg S. A qualitative study showing women’s participation and empowerment in instrumental vaginal births. Women Birth. 2018;31:e185–9.

Zwedberg S, Bjerkan H, Asplund E, Ekeus C, Hjelmstedt A. Fathers’ experiences of a vacuum extraction delivery - a qualitative study. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2015;6:164–8.

Nystedt A, Högberg U, Lundman B. Some Swedish women’s experiences of prolonged labour. Midwifery. 2006;22:56–65.

Goldbort JG. Women’s lived experience of their unexpected birthing process. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2009;34:57–62.

Alexander J, Anderson T, Cunningham S. An evaluation by focus group and survey of a course for midwifery Ventouse practitioners. Midwifery. 2002;18:165–72.

Al-Mufti R, McCarthy A, Fisk NM. Survey of obstetricians’ personal preference and discretionary practice. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1997;73:1–4.

Avasarala S, Mahendran M. A survey of women’s experiences following instrumental vaginal delivery. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;29:504–6.

Belanger-Levesque MN, Pasquier M, Roy-Matton N, Blouin S, Pasquier JC. Maternal and paternal satisfaction in the delivery room: a cross-sectional comparative study. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004013.

Chan KKL, Paterson-Brown S. How do fathers feel after accompanying their partners in labour and delivery? J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;22:11–5.

Crosby DA, Sarangapani A, Simpson A, Windrim R, Satkunaratnam A, Higgins MF. An international assessment of trainee experience, confidence, and comfort in operative vaginal delivery. Ir J Med Sci. 2017;186:715–21.

Declercq E, Cunningham DK, Johnson C, Sakala C. Mothers’ reports of postpartum pain associated with vaginal and cesarean deliveries: results of a national survey. Birth. 2008;35:16–24.

Fauveau V. Is vacuum extraction still known, taught and practiced? A worldwide KAP survey. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;94:185–9.

Fisher J, Astbury J, Smith A. Adverse psychological impact of operative obstetric interventions: a prospective longitudinal study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1997;31:728–38.

Garcia J, Anderson J, Vacca A. Views of women and their medical and midwifery attendants about instrumental delivery using vacuum extraction and forceps. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 1985;4:1–9.

Handelzalts JE, Peyser AW, Krissi H, Levy S, Wiznitzer A, Peled Y. Indications for emergency intervention, mode of delivery, and the childbirth experience. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169132.

Healy DL, Laufe LE. Survey of obstetric forceps training in North America in 1981. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;151:54–8.

Hewson D, Bennett A, Holliday S, Booker E. Childbirth in Sydney teaching hospitals: a study of low-risk primiparous women. Commun Health Stud. 1985;9:195–202.

Kjerulff KH, Brubaker LH. New mothers’ feelings of disappointment and failure after cesarean delivery. Birth (Berkeley, Calif). 2018;45:19–27.

Maclean LI, McDermott MR, May CP. Method of delivery and subjective distress: Women's emotional responses to childbirth practices. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2000;18:153–62.

Nolens B, van den Akker T, Lule J, Twinomuhangi S, van Roosmalen J, Byamugisha J. Birthing experience and quality of life after vacuum delivery and second-stage caesarean section: a prospective cohort study in Uganda. Tropical Med Int Health. 2018;23:914–22.

Ramphul M, O'Brien Y, Murphy DJ. Strategies to enhance assessment of the fetal head position before instrumental delivery: a survey of obstetric practice in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;165:181–8.

Ranta P, Spalding M, Kangas-Saarela T, Jokela R, Hollmén A, Jouppila P, Jouppila R. Maternal expectations and experiences of labour pain--options of 1091 Finnish parturients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1995;39:60–6.

Renner RM, Eden KB, Osterweil P, Chan BK, Guise JM. Informational factors influencing patient’s childbirth preferences after prior cesarean. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:e14–6.

Rijnders M, Baston H, Schonbeck Y, Van Der Pal K, Prins M, Green J, Buitendijk S. Perinatal factors related to negative or positive recall of birth experience in women 3 years postpartum in the Netherlands. Birth. 2008;35:107–16.

Rowlands IJ, Redshaw M. Mode of birth and women’s psychological and physical wellbeing in the postnatal period. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:138.

Ryding EL, Wijma K, Wijma B. Psychological impact of emergency cesarean section in comparison with elective cesarean section, instrumental and normal vaginal delivery. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;19:135–44.

Salmon P, Drew NC. Multidimensional assessment of women’s experience of childbirth: relationship to obstetric procedure, antenatal preparation and obstetric history. J Psychosom Res. 1992;36:317–27.

Sánchez Del Hierro G, Remmen R, Verhoeven V, Van Royen P, Hendrickx K. Are recent graduates enough prepared to perform obstetric skills in their rural and compulsory year? A study from Ecuador. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005759.

Schwappach DLB, Blaudszun A, Conen D, Eichler K, Hochreutener MA, Koeck CM. Women’s experiences with low-risk singleton in-hospital delivery in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2004;134:103–9.

Shaaban MM, Sayed Ahmed WA, Khadr Z, El-Sayed HF. Obstetricians’ perspective towards cesarean section delivery based on professional level: experience from Egypt. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;286:317–23.

Shorten A, Shorten B. The importance of mode of birth after previous cesarean: success, satisfaction, and postnatal health. J Midwifery Women's Health. 2012;57:126–32.

Uotila JT, Taurio K, Salmelin R, Kirkinen P. Traumatic experience with vacuum extraction -- influence of personal preparation, physiology, and treatment during labor. J Perinat Med. 2005;33:373–8.

Waldenström U. Experience of labor and birth in 1111 women. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:471–82.

Wiklund I, Edman G, Ryding EL, Andolf E. Expectation and experiences of childbirth in primiparae with caesarean section. BJOG. 2008;115:324–31.

Wilson B, Thornton JG, Hewison J, Lilford RJ, Watt I, Braunholtz D, Robinson M. The Leeds University maternity audit project. Int J Qual Health Care. 2002;14:175–81.

Wright JB, Wright AL, Simpson NA, Bryce FC. A survey of trainee obstetricians preferences for childbirth. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;97:23–5.

Maaløe N, Sorensen BL, Onesmo R, Secher NJ, Bygbjerg IC. Prolonged labour as indication for emergency caesarean section: a quality assurance analysis by criterion-based audit at two Tanzanian rural hospitals. BJOG. 2012;119:605–13.

Conde AA, Figueiredo B, Costa R, Pacheco A, Pais Á. Perception of the childbirth experience: continuity and changes over the postpartum period. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2008;26:139–54.

Waldenström U. Women’s memory of childbirth at two months and one year after the birth. Birth. 2003;30:248–54.

Downe S, Finlayson K, Oladapo O, Bonet M, Gülmezoglu AM. What matters to women during childbirth: a systematic qualitative review. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0194906.

World Health Organization. WHO Reproductive Health Library. WHO recommendation on respectful maternity care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

Dresang LT, González MMA, Beasley J, Bustillo MC, Damos J, Deutchman M, Evensen A, de Ancheta NG, Rojas-Suarez JA, Schwartz J, et al. The impact of advanced life support in obstetrics (ALSO) training in low-resource countries. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015;131:209–15.

Bahl R, Murphy DJ, Strachan B. Non-technical skills for obstetricians conducting forceps and vacuum deliveries: qualitative analysis by interviews and video recordings. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;150:147–51.

Simpson AN, Hodges R, Snelgrove J, Gurau D, Secter M, Mocarski E, Pittini R, Windrim R, Higgins M. Learning from experience: qualitative analysis to develop a cognitive task list for Kielland forceps deliveries. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37:397–404.

Hotton E, O'Brien S, Draycott TJ. Skills training for operative vaginal birth. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;56:11–22.

Hotton EJ, Renwick S, Barnard K, Lenguerrand E, Wade J, Draycott T, Crofts JF, Blencowe NS. Exploring standardisation, monitoring and training of medical devices in assisted vaginal birth studies: protocol for a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e028300.

Merriel A, Ficquet J, Barnard K, Kunutsor SK, Soar J, Lenguerrand E, Caldwell DM, Burden C, Winter C, Draycott T, et al. The effects of interactive training of healthcare providers on the management of life-threatening emergencies in hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;9:CD012177.

Al Wattar BH, Mahmud A, Janjua A, Parry-Smith W, Ismail KM. Training on Kielland’s forceps: A survey of trainees’ opinions. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;37(3):280–3.

Chinnock M, Robson S. An anonymous survey of registrar training in the use of Kjelland's forceps in Australia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;49(5):515–6.

Bahl R, Murphy D, Strachan B. Decision-making in operative vaginal delivery: when to intervene, where to deliver and which instrument to use? Qualitative analysis of expert clinical practice. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;170(2):333–40.

Funding

This study was funded by UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), Department of Reproductive Health and Research (RHR), World Health Organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

APB, SD and CK designed the review. NC, MCB, CK and APB conducted the searches, identification and screening. NC, MCB, CK and SD carried out quality appraisals and extracted data. CK and NC carried out the qualitative evidence synthesis, and SD and CK carried out the narrative synthesis of quantitative data from surveys and questionnaires. NC, CK and MCB carried out GRADE CERQual to assess confidence in qualitative review findings and SD devised and carried out a modified GRADE CERQual approach to assess confidence in review findings from the narrative synthesis of quantitative data from surveys and questionnaires. NC, CK, SD, APB contributed to writing the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Ana Pilar Betrán is a member of the editorial board of BMC Reproductive Health. The authors have no other competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Search strategy Ovid medline.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Crossland, N., Kingdon, C., Balaam, MC. et al. Women’s, partners’ and healthcare providers’ views and experiences of assisted vaginal birth: a systematic mixed methods review. Reprod Health 17, 83 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-00915-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-00915-w