Abstract

Background

Renal denervation (RDN) is a promising therapeutic method in cardiology. Its currently most investigated indication is resistant hypertension. Other potential indications are atrial fibrillation, type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic renal insufficiency among others. Previous trials showed conflicting but promising results, but the real benefits of RDN are still under investigation. Patients with renal insufficiency and resistant hypertension are proposed to be a good target for this therapy due to excessive activation of renal sympathetic drive. However, only limited number of studies showed benefits for these patients. We hypothesize that in our experimental model of chronic kidney disease (CKD) due to ischemia with increased activity of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS), renal denervation can have protective effects by slowing or blocking the progression of renal injury.

Methods

An experimental biomodel of chronic renal insufficiency induced by ischemia was developed using selective renal artery embolization (remnant kidney porcine model). 27 biomodels were assessed. Renal denervation was performed in 19 biomodels (denervated group), and the remaining were used as controls (n = 8). The extent of renal injury and reparative process between the two groups were compared and assessed using biochemical parameters and histological findings.

Results

Viable remnant kidney biomodels were achieved and maintained in 27 swine. There were no significant differences in biochemical parameters between the two groups at baseline. Histological assessment proved successful RDN procedure in all biomodels in the denervated group. Over the 7-week period, there were significant increases in serum urea, creatinine, and aldosterone concentration in both groups. The difference in urea and creatinine levels were not statistically significant between the two groups. However, the level of aldosterone in the denervated was significantly lower in comparison to the controls. Histological assessment of renal arteries showed that RDN tends to produce more damage to the arterial wall in comparison to vessels in subjects that only underwent RAE. In addition, the morphological damage of kidneys, which was expressed as a ratio of damaged surface (or scar) to the overall surface of kidney, also did not show significant difference between groups.

Conclusions

In this study, we were not able to show significant protective effect of RDN alone on ischemic renal parenchymal damage by either laboratory or histological assessments. However, the change in aldosterone level shows some effect of renal denervation on the RAAS system. We hypothesize that a combined blockade of the RAAS and the sympathetic system could provide more protective effects against acute ischemia. This has to be further investigated in future studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Renal denervation (RDN) is a promising therapeutic method in cardiology [1]. Potential indications for renal denervation are treatments for resistant hypertension, sleep apnea syndrome, insulin resistance, atrial fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, and chronic renal insufficiency [2, 3]. Initially, Symplicity HTN-1, Symplicity HTN-2, and other smaller trials showed promising results of RDN as a potential treatment modality [4,5,6,7]. However, Symplicity HTN-3 trial showed less encouraging results; it confirmed the safety of the technique without proving the efficacy of renal denervation as a treatment option [8]. Nonetheless, the real benefits of this method are still under investigations. Recent studies showed moderate to equivocal effects in specific study populations [9, 10]. Patients with renal insufficiency and resistant hypertension were proposed to be the best target population for this therapy due to excessive activation of renal sympathetic drive [11]. Very few reports exist that show benefits for these patients. In our experimental model of Chronic Kidney Diseases (CKD) established by induced ischemia, we hypothesize that renal sympathetic denervation can have protective effects by slowing or blocking the progression of renal injury. The aim of our study was to assess the effects of RDN on the progression of chronic renal insufficiency through an experimental model of CKD. The extent of renal injury and reparative process were assessed using laboratory parameters and histology.

Methods

We used the porcine remnant kidney model of chronic renal insufficiency that was developed by Misra and his coworkers [12]. This biomodel was created using renal artery embolization with PVA particles. A stable and reproducible model of renal insufficiency in swine developed by the 4th week and lasted up to 12 weeks. Total left and partial right nephrectomies were performed to develop this model. Acute deterioration of renal functions ensued after embolization, but improves and stabilizes soon after. Renal insufficiency was later confirmed by a statistically significant increase in creatinine, BUN, and transient changes in blood pressure. The remnant kidney eventually developed fibrosis in the tubulointerstitial compartment as it hypertrophies in the late stage.

Cross-bred swine (Landrace × White; 44 ± 3 kg) were used for this experiment in an accredited university laboratory by a skilled team of clinicians and veterinary specialists. The animals were handled in accordance with the guidelines of research animal use [13]. The protocol was approved by the Charles University 1st Faculty of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and the procedures were performed at the Animal Laboratory, Institute of Physiology, 1st Faculty of Medicine, Charles University in Prague in accordance with Act No 246/1992 as amended, Collection of Laws, Czech Republic, and EU Directives 86/609/EEC as amended, 2007/526/ES, 2010/63/EU.

The experiment was conducted on a total of 27 swine. The population was divided into two groups: a control group (n = 8) and a denervated group (n = 19). Experimental animals underwent general anesthesia, and after renal and hemodynamic parameters had been collected to establish baseline parameters, 19 animals (denervated group) underwent renal denervation in addition to renal artery embolization (RAE) done on all 27 animal subjects. After the procedure, data on renal function, hemodynamics, serum renin and aldosterone were obtained. After 42 days, post-procedural follow-ups and re-tests of renal and hemodynamic parameters were conducted, the swine were then euthanized for histological assessments. One to two procedures were performed monthly; all procedures on swine were concluded during the first 24 months of study, then data analyses were performed the year after.

Anesthesia and monitoring

The pigs were sedated by intramuscular application of azaperone (2–3 mg/kg) and ketamine (20 mg/kg). The marginal ear vein was cannulated, and general anesthesia was induced by an intravenous bolus of propofol (1–2 mg/kg). After preoxygenation via facial mask, orotracheal intubation was performed. During the experiment, biomodels were mechanically ventilated using Intellivent-ASV closed-loop system (G5, Hamilton Medical, Bondauz, Switzerland) to maintain normoxia (SpO2 98%) and normocapnia (EtCO2 38–40 mmHg) respective to the actual metabolic rate. The total intravenous anesthesia was maintained by continuous administration of propofol (6–12 mg/kg/h) and morphine (0.1–0.2 mg/kg/h). The depth of anesthesia was regularly assessed by photoreaction and corneal reflex and adjusted accordingly. Intravenous infusion of Ringer’s solution was given to reach and maintain central venous pressure between 6 and 8 mmHg. Anticoagulation was provided by unfractionated heparin bolus (100 IU/kg IV), followed by continuous intravenous drip (40–50 IU/kg/h) to maintain target activated clotting time of 180–250 s (values checked every hour with Hemochron Junior+, International Technidyne Corporation, Edison, NJ, USA). Sheaths and catheters were inserted into femoral and carotid/jugular vessels as needed. Invasive blood pressure from carotid and pulmonary arteries, central venous pressure (TruWave, Edwards Lifesciences, USA), body surface ECG, capnometry and pulse oximetry were continuously monitored by bedside monitor (Life Scope TR, Nihon Kohden, Japan). All procedures were performed under completely sterile environment to avoid infection and contamination. This technique used for anesthesia and monitoring has been described in our previous publication [14].

Renal denervation

After initiation of general anesthesia and mechanical ventilation, an 8 French sheath was placed into the right common femoral artery under ultrasound guidance, and 6 French sheath was then introduced into the right common femoral vein. The later was used for the acquisition of samples for biochemical analysis during the procedure. According to the protocol, after preliminary samples were withdrawn, renal angiography was performed, and an ablation catheter was then introduced into the renal arteries. In 6 cases, the EnligHTN™ catheter (St. Jude Medical, USA) was used, in 8 cases we used the Symplicity catheter (Medtronic, USA), and in 5 cases the ThermoCool® catheter (Biosense Webster) was used. The ablation procedure was performed according to the instructions for the use of each device in both arteries in each case, and the effect of the procedure was controlled by a drop of impedance of at least 10% (Table 1). Finally, the femoral sheath was removed and the femoral artery was surgically sutured. After this, the administration of anesthetics and analgesics ceased and successful weaning from artificial ventilation was achieved. The animals were then extubated. For the next 42 days, the animals were bred in a certified menagerie.

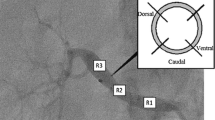

Renal artery embolization

Selective angiography of the renal artery was performed using a predefined protocol. Using a guiding catheter, the left renal artery was cannulated and 40 ml of Bead Block® (BTG Inc.) (300–500 μm) was applied; the left renal artery had to be completely occluded. Subsequently, the right renal artery was also cannulated, and the right upper branch was used as the target vessel where 20 ml of Bead Block (300–500 μm) was injected to achieve partial nephrectomy. Control angiography was performed showing complete occlusion of the left renal artery and partial occlusion of the right upper branch.

Statistics

The sample size was calculated using Medcalc software (Medcalc® Version 12,1.4.0) based on the primary outcome of the study, which was the difference of creatinine concentration between the denervated and the control group at follow-up. The minimal required sample size per group for equal samples sizes for alpha = 0.05 and power = 0.80 (beta = 0.20) was 15 per group, assuming that the data will be normally distributed.

Continuous data are presented as mean ± SD or median [25th–75th percentile] as appropriate. Categorical data are presented as proportions. Due to the non-normal distribution of several continuous variables, nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare baseline variables and histology data. Baseline categorical variables were compared using the Chi square test. Change of laboratory values in time, comparisons between groups at follow-up and differences in change of laboratory values was assessed using linear mixed modeling; serum creatinine and blood urea values were log-transformed for the analysis to better accommodate the linear model assumptions. p < 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analysis and plotting were performed using R software, version 3.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

RDN procedure parameter

Main parameters of renal denervation are shown in Table 1. The mean energy delivered to the tissues were sufficient, and the increase in temperature was adequate. The drop in impedance showed that all radiofrequency ablation with all three devices were effective.

Biochemical changes

The baseline characteristics of the study population are recapitulated in Table 2. There was no significant difference in renal parameters between groups (denervated vs controls: Urea 3.10 [2.85–3.27] mmol/l vs. 3.10 [2.47–3.80] mmol/l, p = NS, creatinine 109 [104–128] µmol/l vs. 118 [93–126] µmol/l, p = NS). We were able to develop the ischemic model in all surviving animals.

The creatinine level estimate increased from baseline to maximal value, and finally remained at a high level in both groups as shown in Table 4. Creatinine values at 7th week were significantly higher both compared to Baseline and 4th week. This shows that we were able to establish a successful model of renal ischemia through renal artery embolization, and we managed to sustain the viability of a large group of animal subjects over a long period of time (Table 3). Although serum sodium and chloride levels were observed to be different among the two groups; overall, the baseline p values of most serum compounds in controls and denervated show that there were no significant differences among the Denervated group and the Controls at baseline (Table 2).

Over the 7-week period, there were significant changes in serum urea, creatinine, and aldosterone concentration in both groups, but the difference between two groups was not statistically significant for urea and creatinine levels at both week 4 and week 7 follow-up. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in change of the values over time (Table 4, Figs. 1, 2). This shows that renal denervation did not provide specific protection to prevent renal parenchymal damage by ischemia. However, the level of aldosterone in the denervation group decreased from baseline and was significantly lower in comparison to the control group. This shows that renal denervation could have a mild protective effect by interfering with the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone (RAAS) system (Fig. 3).

Histology findings

The histological findings in renal arteries are shown in Table 5. We assessed the level of injuries in each layer of the arterial wall according to the histologic vascular injury grading scale (0–5) [15]. As seen in the table, arteries without renal denervation tend to have less damage compared to the denervation group since no manipulation to the artery was applied apart from renal artery embolization.

A cross-section of the denervated renal artery can be seen with increased inflammation around the intima and the destroyed nerves (Figs. 4, 5). The morphological damage of kidneys expressed as a ratio of damaged surface (or scar) to overall surface of the kidney also did not show significant difference between groups (Table 5).

Discussion

Renal denervation is a therapeutic method which was expected to impact the treatment of chronic renal insufficiency [16, 17]. This concept is widely accepted because the increase of sympathetic activity is one of the important factors that contributes to chronic kidney damage [18, 19]. Experimental studies with stimulation of the sympathetic system have shown increase release of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone and other agents from kidney. Moreover, markers of sympathetic activity such as MSNA, noradrenaline, and neuropeptide Y, are elevated in CKD patients on average, but show considerable variation in different studies [20, 21]. Thus, we hypothesize that blocking sympathetic system by RDN would have a protective effect against renal damage caused by ischemia. First, we developed a sustained biomodel of chronic renal insufficiency on which we could then test our hypothesis. Developing a sustained biomodel was a considerable achievement considering the risk of loss-of-animal during the acute phase. The increase in serum creatinine was dramatic after the initial renal embolization. However, there were no significant differences in changes of urea and creatinine levels between the controls and the denervated group; this may be because the initial ischemia causes dramatic increases in the sympathetic activity during the acute phase, and renal denervation has only a limited effect on that massive hyperactivity. RDN alone is not sufficient to curb that hyperactivation [17, 22, 23]. However, a minor change was observed in the denervated group (the lower of aldosterone level), which shows that renal denervation could have a mild protective effect through its interference with the renin–aldosterone–angiotensin (RAAS) system. This has to be investigated further in future studies. It will be of interest to investigate the combined effect of RAAS blockade and RDN on this biomodel. Moreover, newer techniques used to modulate the sympathetic system are emerging, such as carotid body ablation or barostimulation [24,25,26,27,28,29]. The effects of these techniques as potential treatment modalities for resistant hypertension and chronic renal insufficiency also need to be investigated further.

Study limitation

In our study, we were not able to measure renin level at follow up because of technical problems therefore we cannot reliably comment on that parameter although we hypothesized that renin levels would have shown the same trend as aldosterone. Also, the number of controls which was planned to be higher was subsequently limited because of our preliminary results showing consistent trend in both groups. After interim analysis, it was clear that adding more controls will not increase the statistical power of the experiment. Another limitation of our study is that Renal denervation and renal artery embolization were performed during baseline at the same time point which made controlling excessive activation of the sympathetic system by acute ischemia impossible. Interestingly, it would be quite challenging to limit the effects of acute ischemia by establishing the CKD biomodel first and then perform RDN when the renal insufficiency is stable. This would require also a longer duration of the whole experiment. This approach would eliminate the acute effects of ischemia and uncover the real effects of renal denervation on chronically increased sympathetic drive which is not the case in the present study.

Conclusions

With this experiment, we were able to establish an experimental model of chronic renal insufficiency by embolization of renal artery. Unfortunately, we were not able to show significant protective effects of renal denervation alone on renal parenchyma damage caused by ischemia. However, the change in aldosterone level shows some effect of renal denervation on the RAAS system. We hypothesize that a combined blockade of the RAAS and the sympathetic system might be more protective against acute ischemia, but this has to be investigated further in future studies.

Abbreviations

- RAAS:

-

renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system

- CKD:

-

chronic kidney diseases

- RDN:

-

renal sympathetic denervation

- RAE:

-

renal artery embolization

References

Members Task Force, Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2013;2013(31):1281–357.

Sarganas G, Neuhauser HK. Untreated, Uncontrolled, and apparent resistant hypertension: results of the German health examination survey 2008–2011. J Clin Hypertens. 2016;18:1146–54.

Doumas M, Faselis C, Papademetriou V. Renal sympathetic denervation and systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105(4):570–6.

Krum H, Schlaich M, Whitbourn R, Sobotka PA, Sadowski J, Bartus K, Kapelak B, Walton A, Sievert H, Thambar S, Abraham WT, Esler M. Catheter-based renal sympathetic denervation for resistant hypertension: a multicentre safety and proof-of-principle cohort study. Lancet. 2009;373(9671):1275–81.

Symplicity HTN-2 Investigators, Esler MD, Krum H, Sobotka PA, Schlaich MP, Schmieder RE, Böhm M. Renal sympathetic denervation in patients with treatment-resistant hypertension (The Symplicity HTN-2 Trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1903–9.

Daugherty SL, Powers JD, Magid DJ, et al. Incidence and prognosis of resistant hypertension in hypertensive patients. Circulation. 2012;125:1635–42.

Persu A, Jin Y, Azizi M, et al. Blood pressure changes after renal denervation at 10 European expert centers. J Hum Hypertens. 2014;28:150–6.

Bhatt DL, Kandzari DE, O’Neill WW, et al. SYMPLICITY HTN-3 Investigators. A controlled trial of renal denervation for resistant hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1393–401.

Mathiassen ON, Vase H, Bech JN, et al. Renal denervation in treatment-resistant essential hypertension. A randomized, SHAM-controlled, double-blinded 24-h blood pressure-based trial. J Hypertens. 2016;34:1639–47.

Desch S, Okon T, Heinemann D, et al. Randomized SHAM-controlled trial of renal sympathetic denervation in mild resistant hypertension novelty and significance. Hypertension. 2015;65:1202–8.

Martinez-Maldonado M. Role of hypertension in the progression of chronic renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2001;16(Suppl 1):63–6.

Misra S, Gordon JD, Fu AA, Glockner JF, Chade AR, Mandrekar J, Lerman L, Mukhopadhyay D. The porcine remnant kidney model of chronic renal insufficiency. J Surg Res. 2006;135(2):370–9.

McGlone JJ, Swanson J. Update on the guide for the care and use of agricultural animals in research and teaching. J Dairy Sci. 2010;93:12–12.

Lubanda JC, Kudlicka J, Mlcek M, Chochola M, Neuzil P, Linhart A, Kittnar O. Renal denervation decreases effective refractory period but not inducibility of ventricular fibrillation in a healthy porcine biomodel: a case control study. J Transl Med. 2015;16(13):4. doi:10.1186/s12967-014-0367-y.

Rippy MK, Zarins D, Barman NC, Wu A, Duncan KL, Zarins CK. Catheter-based renal sympathetic denervation: chronic preclinical evidence for renal artery safety. Clin Res Cardiol. 2011;100(12):1095–101.

Hering D, Mahfoud F, Walton AS, Krum H, Lambert GW, Lambert EA, et al. Renal denervation in moderate to severe CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1250–7. doi:10.1681/ASN.2011111062.

Sanders MF, Blankestijn PJ. Chronic kidney disease as a potential indication for renal denervation. Front Physiol. 2016;8(7):220. doi:10.3389/fphys.2016.00220.

Converse RL Jr, Jacobsen TN, Toto RD, Jost CM, Cosentino F, Fouad-Tarazi F, Victor RG. Sympathetic overactivity in patients with chronic renal failure. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1912–8.

Klein IE, Ligtenberg G, Oey PL, Koomans HA, Blankestijn PJ. Sympathetic activity is increased in polycystic kidney disease and is associated with hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:2427–33.

Zoccali C, Mallamaci F, Parlongo S, Cutrupi S, Benedetto FA, Tripepi G, et al. Plasma norepinephrine predicts survival and incident cardiovascular events in patients with end-stage renal disease. Circulation. 2002;105:1354–9. doi:10.1161/hc1102.105261.

Zoccali C, Mallamaci F, Tripepi G, Benedetto FA, Parlongo S, Cutrupi S, et al. Prospective study of neuropeptide y as an adverse cardiovascular risk factor in end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2611–7. doi:10.1097/01.ASN.0000089026.28617.33.

Hausberg M, Kosch M, Harmelink P, Barenbrock M, Hohage H, Kisters K, Dietl KH, Rahn KH. Sympathetic nerve activity in end-stage renal disease. Circulation. 2002;106:1974–99.

Neumann J, Ligtenberg G, Klein IE, Boer P, Oey PL, Koomans HA, Blankestijn PJ. Sympathetic hyperactivity in hypertensive chronic kidney disease patients is reduced during standard treatment. Hypertension. 2007;49:506–10.

Scheffers IJ, Kroon AA, Schmidli J, et al. Novel baroreflex activation therapy in resistant hypertension: results of a European multi-center feasibility study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1254–8.

Bisognano JD, Bakris G, Nadim MK, et al. Baroreflex activation therapy lowers blood pressure in patients with resistant hypertension: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled rheos pivotal trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:765–73.

Hoppe UC, Brandt M-C, Wachter R, et al. Minimally invasive system for baroreflex activation therapy chronically lowers blood pressure with pacemaker-like safety profile: results from the Barostim neo trial. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2012;6:270–6.

Wallbach M, Lehnig L-Y, Schroer C, et al. Effects of baroreflex activation therapy on ambulatory blood pressure in patients with resistant hypertension novelty and significance. Hypertension. 2016;67:701–9.

Lobo MD, Sobotka PA, Stanton A, et al. Central arteriovenous anastomosis for the treatment of patients with uncontrolled hypertension (the ROX CONTROL HTN study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:1634–41.

Veelken R, Schmieder RE. Renal denervation-implications for chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10(6):305–13. doi:10.1038/nrneph.2014.59.

Authors’ contributions

JCL is the principal investigator and was responsible for the design and implementation of the project, its coordination in cooperation with the Physiology, Pathology, Biochemistry Institute, and Department of Cardiology Hospital in Homolka. He was also responsible for monitoring the data and for the preparation of the publications. He guarantees the authenticity of the data. He performed all interventional procedures (RDN and RAE). AL, SK, and MC were responsible for the design of the project, analyzing the data and preparation of the publications. MC was responsible for interventional procedures, especially for the development of the experimental model and data acquisition during the experiment. MM was responsible for carrying out all activities related to preparation of the biomodels, periprocedural and postprocedural intensive care. He was the main coordinator for the project at the Institute of Physiology. PN and SH were responsible for the execution of renal denervation using RDN and obtaining relevant data in the electrophysiological part of the project. ZF was responsible for support during EP procedures and data management, AH (KHAH) was responsible for data management, preparation for publication and assistance during the procedures. JM was responsible for data management, all statistics, and preparation of the publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions from Tereza Vavřinová from the Institute of Physiology for her support during all experiments, Stano Lacko for technical support for EP and RF energy delivery and Martina Striteská for administrative support of all the project. We also acknowledge the contributions from Dr. Galko and Dr. Vitkova for the histopathological examination of all samples and Dr. Benakova for biochemical analysis of all laboratory samples (RENP, APA, mineralograms, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine etc.).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol was approved by the Charles University 1st Faculty of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Funding

Financial support was provided by the grant PROGRESS of Charles University. The funding body did not have any role in the design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in the writing of the manuscript.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lubanda, JC., Chochola, M., Mlček, M. et al. The effect of renal denervation in an experimental model of chronic renal insufficiency, The REmnant kidney Denervation In Pigs study (REDIP study). J Transl Med 15, 215 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-017-1319-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-017-1319-0