Abstract

Background

Reducing meat consumption can help prevent non-communicable diseases and protect the environment. Interventions targeting conscious determinants of human behaviour are generally acceptable approaches to promote dietary change, but little is known about their effectiveness to reduce the demand for meat.

Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness of interventions targeting conscious determinants of human behaviour to reduce the demand for meat.

Methods

We searched six electronic databases on the 31st of August 2017 with a predefined algorithm, screened publicly accessible resources, contacted authors, and conducted forward and backward reference searches. Eligible studies employed experimental designs to evaluate interventions targeting conscious determinants of human behaviour to reduce the consumption, purchase, or selection of meat in comparison to a control condition, a baseline period, or relative to other eligible interventions. We synthesised results narratively and conducted an exploratory crisp-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis to identify combinations of intervention characteristics associated with significant reductions in the demand for meat.

Results

We included 24 papers reporting on 59 interventions and 25,477 observations. Self-monitoring interventions and individual lifestyle counselling led to, or were associated with reduced meat consumption. Providing information about the health or environmental consequences of eating meat was associated with reduced intentions to consume and select meat in virtual environments, but there was no evidence to suggest this approach influenced actual behaviour. Education about the animal welfare consequences of eating meat was associated with reduced intentions to consume meat, while interventions implicitly highlighting animal suffering were not. Education on multiple consequences of eating meat led to mixed results. Tailored education was not found to reduce actual or intended meat consumption, though few studies assessed this approach.

Conclusion

Some interventions targeting conscious determinants of human behaviour have the potential to reduce the demand for meat. In particular, self-monitoring interventions and individual lifestyle counselling can help to reduce meat consumption. There was evidence of effectiveness of some educational messages in reducing intended consumption and selection of meat in virtual environments.

Protocol registration

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Red and processed meat consumption is associated with an increased risk of developing some non-communicable chronic conditions, including cardiovascular disease [1,2,3], type-2-diabetes [3,4,5], and some forms of cancer [6,7,8]. Additionally, livestock negatively affects the natural environment and advances anthropogenic climate change [9,10,11]. These environmental changes might in turn affect human health by contributing – among other things – to the pollution of air and drinking water, the rise in antimicrobial resistance, and the spread of vector-borne diseases [12,13,14]. While the potential health and environmental benefits of reducing meat consumption are well established, concerns about a consumer backlash and the poor understanding of how to promote this behaviour change have contributed to a general state of inaction [15,16,17]. Interventions targeting conscious determinants of human behaviour, such as those providing information, are generally perceived to be acceptable approaches to promote health behaviours by the public in developed countries [18, 19] and might therefore help to overcome this state of inaction. Furthermore, interventions targeting conscious determinants of human behaviour might, over time, enhance the public’s support for more structural interventions aiming at reducing the demand for meat [15, 16, 20]. Accordingly, identifying effective interventions targeting conscious determinants of human behaviour to reduce the demand for meat is an important step towards promoting healthier and more environmentally sustainable diets. The aim of this systematic review is to synthesise the evidence from studies evaluating the effectiveness of interventions targeting conscious determinants of human behaviour to reduce the actual or intended consumption, purchase, and selection of meat and to identify combinations of intervention characteristics that effectively promote this behaviour change.

Methods

Protocol registration and eligibility criteria

A protocol for this systematic review was published on PROSPERO [21]. This review includes studies evaluating interventions targeting conscious determinants of human behaviour to reduce the consumption, purchase, or selection of meat, and that fulfilled the eligibility criteria outlined in Table 1.

We extracted data on participants’ demand for meat, defined as the actual or intended consumption, purchase, or selection of meat. We refer to meat purchases when the selection of meat involves a real or virtual monetary transaction, while we refer to meat selection when no form of monetary transaction is involved. Where reported, we also extracted data pertaining to attitudes, subjective social norms, and perceived behavioural control of eating, purchasing, or selecting meat, and on body weight, blood pressure, blood glucose, and blood lipids. When an outcome was assessed in multiple ways we only extracted data for the most granular measure (e.g. food diary > self-reported score of change) referring to the longest time-span (e.g. consumption over a month > consumption over a week). There were no exclusion criteria pertaining to the length of follow-up, publication status, publication year, or language.

Search strategy and data extraction

We searched six electronic databases on the 31st of August 2017 using a pre-specified search algorithm (Additional file 1: Table S1). We searched for further eligible records contacting researchers and experts, manually conducting forward and backward reference searches, and screening publicly accessible online resources following the methodology described by Stansfield et al. ( [22], Additional file 1: Table S2). Two members of the research team independently assessed the eligibility of the studies, extracted data from eligible records using a pre-piloted data extraction form, and evaluated the methodological quality of all eligible studies using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies [23]. Where additional information was required, we contacted authors and/or reviewed study protocols. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and by referral to a third member of the research team.

Data synthesis

We synthesised results narratively grouping interventions in five categories: (1) individual lifestyle counselling, (2) goal-setting and self-monitoring interventions, (3) non-tailored education (about meat consumption and one or more of health, the environment, animal welfare, socio-economic issues), (4) tailored education, and (5) interventions implicitly highlighting animal suffering. We augmented our narrative synthesis with an exploratory crisp-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA). In our QCA we used a binary coding system to categorise each intervention as presenting or not presenting specific behavioural strategies or implementation features to identify configurations of intervention characteristics associated with (and those not associated with) statistically significant (p < 0.05) reductions in the demand for meat at the follow-up closest to the intervention completion. Where studies reported results for multiple eligible outcomes we only considered the outcome closest to ‘actual behaviour’ (actual behaviour > behaviour in virtual environments > intention). The intervention characteristics included in QCA pertained to whether an intervention provided information about the (a) health, (b) environmental, (c) animal welfare, (d) socio-economic, (e) and multiple consequences of meat consumption, and whether it (e) provided tailored information, (f) employed self-monitoring strategies, (g) employed goal-setting strategies, (h) implicitly highlighted animal suffering, (i) implemented individual lifestyle counselling sessions, (j) targeted people with, or at increased risk of ill-health (k) provided information on ‘how to’ eat less meat, and whether (l) the outcome was actual as opposed to intentions or behaviour in virtual environments. In QCA we included comparisons between interventions and no-intervention controls or pre-intervention baselines, while comparisons between multiple interventions were excluded. A more detailed account on QCA in systematic reviews is outlined by Thomas et al. [24].

Results

Study selection

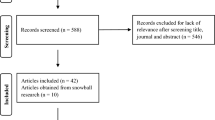

We screened 10,733 titles/abstracts, assessed the full-text of 60 papers, and included 24 papers reporting on 29 studies and 59 intervention conditions (Fig. 1). The majority of papers (54%) were published or written between 2015 and 2017.

Study characteristics

This review includes 25,477 observations (i.e. individuals or individual meal purchases) at the follow-up closest to the intervention completion and 305 observations at the longest follow-up for the four studies reporting on multiple end-points. Where reported, mean age ranged from 19 to 74 years (median = 36), the proportion of female participants ranged from 49 to 100% (median = 61%), the proportion of white participants ranged from 58 to 83% (median = 75%), and participants’ education and/or household income were high in most studies. Forty-five percent of studies only included individuals who ate meat. Studies recruited individuals (N = 26) or food providers (N = 3) through active recruitment (N = 15), advertisement and passive recruitment (N = 8), or through online panels (N = 6). Studies were conducted in Europe (N = 12), the USA (N = 9), China (N = 2), New Zealand (N = 2), and Brazil (N = 1), and were implemented in various settings, including experimental settings (N = 18), canteens or food services (N = 3), healthcare settings (N = 2), and among free-living individuals (N = 6). Fourteen studies employed a randomised controlled trial (RCT), 5 employed a non-randomised controlled trial (CT), 1 study employed a crossover design, 7 employed a pre-post design, and 2 studies retrospectively evaluated the intervention effectiveness. Retention at the shortest follow-up ranged from 59 to 100% (median = 95%). The overall methodological quality was ‘strong’ for 6 studies, ‘medium’ for 10 studies, and ‘weak’ for 13 studies. Table 2 summarises the characteristics of all studies included.

Interventions and outcomes

We included 37 interventions providing non-tailored information about meat consumption and health (N = 11), the environment (N = 8), animal welfare (N = 2), socio-economic issues (N = 2), or a combination thereof (N = 14). Ten interventions provided tailored education, four implicitly highlighted animal suffering, six delivered individual lifestyle counselling, and two delivered self-monitoring interventions. Of all interventions included, two interventions targeted food suppliers while the rest targeted consumers. Fifteen studies reported on participants’ actual meat consumption, 6 on meat purchase or selection, and 15 on intended consumption. Fifteen studies additionally reported on other pre-specified secondary psychosocial outcomes or biomarkers of health risk. Table 3 summarises each intervention and its impact on, or association with participants’ demand for meat at the shortest follow-up. The results for the longest follow-up and for other secondary psychosocial and biological outcomes are summarized in Additional file 1: Tables S3, S4, and S5.

Interventions’ impact on the demand for meat

Individual lifestyle counselling

Six studies (N = 2 RCT, N = 1 CT, N = 3 pre-post) evaluated the effectiveness of six lifestyle counselling interventions to reduce red and/or processed meat consumption [25,26,27,28,29,30]. All found evidence that lifestyle counselling led to [25, 26] or was associated with reduced meat consumption [27,28,29,30]. However, two studies measuring red and processed meat separately, only found significant reductions in the consumption of the latter [28, 29]. Lifestyle counselling interventions were delivered individually by a trained health professional through multiple face-to-face and/or phone sessions and lasted from 6 weeks [28, 29] to 1 year. All counselling interventions additionally comprised written supporting material, with two interventions tailoring this material to individuals [25, 26]. Lifestyle counselling promoted behavioural changes other than meat consumption, including one or more of fruit and vegetable consumption, multivitamin supplement usage, smoking cessation, physical activity, weight loss, and reduction in alcohol consumption. Most counselling interventions (N = 5) targeted individuals affected by, or at increased risk of chronic diseases [25, 27,28,29,30], and only one such intervention targeted healthy working-class individuals [26].

Self-monitoring interventions

Evidence from two RCTs suggested that two self-monitoring interventions reduced red [31] and processed meat consumption [32] during the intervention period and increased intentions to not exceed recommended levels of meat consumption over the week following the intervention. Both interventions lasted 1 week and comprised daily text-messages encouraging participants to self-monitor their red or processed meat consumption with the goal of not exceeding pre-specified recommendations. The intervention focussing on processed meat additionally encouraged participants to think about ‘the regret they could experience’ if they exceeded the recommendations [32].

Education on meat consumption and health

Five studies (N = 2 RCT, N = 1 CT, N = 1 CO, N = 1 Pre-post) evaluated seven interventions providing written information [33,34,35,36] or informational videos [37] about the health consequences of eating meat. Of these, five interventions led to [33, 37], or were associated with intended reductions in meat consumption directly post-intervention [35, 36]. Among these studies, one RCT found this effect to be sustained 1 week after the intervention [37]. Conversely, neither a cognitively framed nor an affectively framed message about the health consequences of eating meat were found to be associated with intended reductions in meat consumption directly post-intervention and/or 3 weeks later [34]. Two studies (N = 1 RCT, N = 1 CT) assessed the impact of two health focussed educational interventions on actual meat consumption but neither found evidence of an effect [34, 37]. Finally, one controlled trial including elderly people compared the effect of four interventions on the selection of meat in a virtual environment and found that messages on meat consumption and health more effectively reduced the selection of meat products when framed factually (i.e. describing the causal link between meat consumption and its consequences) rather than pre-factually (i.e. outlining hypothetical consequences of hypothetical present meat consumption) [38]. Conversely, messages on meat consumption and well-being more effectively reduced intended meat consumption when framed pre-factually rather than factually [38].

Education on meat consumption and the natural environment

Six studies (N = 3 RCT, N = 1 CO, N = 2 Pre-post) evaluated eight interventions providing written information about the environmental consequences of meat consumption [33, 35, 36, 39,40,41]. Six interventions led to [33, 39, 40] or were associated with increased intentions to eat less meat [35, 36] or with fewer meat products being selected in a simulated food choice experiment [40]. These interventions provided information in the form of paragraphs [35, 39], brief articles [36, 40], or websites [33] and two interventions also outlined practical strategies to aid reductions in meat intake [33, 35]. Conversely, one pre-post study found no evidence to suggest that two informational posters on livestock’s water footprint reduced meat purchases in a university canteen [41].

Education on meat consumption and animal welfare

Two studies (N = 1 crossover, N = 1 pre-post) evaluated two interventions providing written information about the animal welfare implications of consuming meat [35, 36]. Both were associated with significant reductions in intended meat consumption, and showed more promise than comparable messages on the impact of meat consumption on health or the environment. There was no study assessing the impact of such interventions on actual consumption, purchase, or selection of meat.

Education on meat consumption and social issues

Two studies (N = 1 CT, N = 1 pre-post) evaluated two interventions focussing on the social consequences or antecedents of eating meat [36, 42]. Providing information about the association between pursuing high meat diets and holding social dominance values was not found to be associated with reductions in intended consumption directly post-intervention or with actual meat consumption 3 weeks later [42]. Conversely, reading an article on the adverse social consequences of high meat diets was associated with increased intentions to eat less meat, though it offered less promise than similar articles on meat consumption and health, the environment, or animal welfare [36].

Education on multiple consequences of meat consumption

Nine studies (N = 4 RCT, N = 1 CT, N = 2 Pre-post, N = 2 retrospective evaluations) assessed 14 interventions providing written information about multiple consequences of meat consumption [34, 43,44,45,46,47]. These interventions provided printed or online information about two or more of health, environmental, animal welfare, social, personal appearance, and economic consequences of eating meat. The impact on actual meat consumption was evaluated in seven interventions: two were associated with lower meat intakes directly and 4 weeks post-intervention in pre-post studies [45], four were not found to effectively reduce meat intakes in RCTs [44], and there was insufficient data to make inferences about the effectiveness of the last intervention [34]. There was no evidence that any of five interventions reduced intended consumption directly post-intervention [43] or 3 weeks later [34], while a pre-post study suggested that providing information about the health and environmental consequences of meat consumption was associated with reduced meat selection in a virtual food choice experiment [46]. Actual food purchases were measured following two interventions providing the Meatless Monday toolkit to the US government/corporate accounts or the US healthcare accounts of a large food service company. Only the latter intervention was associated with significant declines in meat purchases [47]. In summary, four of 14 interventions providing written information about multiple consequences of eating meat were associated with significant reductions in meat consumption, purchases or selection, though none of these interventions was assessed in a RCT.

Tailored education

Four RCTs evaluated ten tailored educational interventions, none of which was found to effectively reduce actual [44] or intended meat consumption [43]. Specifically, providing information that was matched to participants’ stage of change (for an account on the stages of change model refer to [48]) for eating less beef was not found to reduce beef consumption in two RCTs, and there was no robust evidence that this tailored intervention outperformed its stage-mismatched equivalent [44]. Two RCTs found no evidence that messages tailored to participants’ most valued consequence of meat consumption, and/or to participants’ self-schema (being responsible, or adventurous, or compassionate, or logical), and/or participants’ personal levels of meat intakes reduced their intended meat consumption [43].

Interventions implicitly highlighting animal suffering

Two RCTs found no evidence that any of four interventions implicitly highlighting animal suffering reduced intended meat consumption [49]. All such interventions employed a combination of visual and written material leading recipients to reflect upon the animal suffering involved in the production of meat [49]. For example, participants were shown a picture of a cow accompanied by the statement that the cow will be send to a slaughterhouse, and were asked to think about what would happen to the animal. None of the aforementioned studies assessed actual meat consumption or purchases.

Qualitative comparative analysis

Fifty-five comparisons were included in QCA. Four configurations of intervention characteristics were consistently associated with reductions in actual or intended meat consumption in real or virtual environments among two or more intervention evaluations (Table 4), while six configurations were consistently not found to be associated with these outcomes (Table 5). QCA supported the findings of the narrative synthesis suggesting that the approaches that were consistently associated with reductions in actual meat consumption were self-monitoring and lifestyle counselling interventions. Non-tailored information provision about the detrimental health or environmental consequences of eating meat was consistently associated with reductions in intended consumption or purchases/selection of meat in virtual environments but was not found to be associated with changes in actual behaviour. Tailored and non-tailored interventions elaborating on several consequences of eating less meat and interventions implicitly highlighting animal suffering were not found to be associated with actual or intended consumption, purchase, or selection of meat in real or virtual environment.

Secondary psychosocial outcomes

Self-monitoring interventions led to more favourable instrumental attitudes (beliefs about the impact of eating meat) but not affective attitudes (feeling about the hedonic aspects of eating meat) towards eating less meat [31, 32]. One self-monitoring intervention additionally enhanced perceived behavioural control [31], while there was no evidence that either influenced subjective social norms [31, 32]. In all five interventions evaluating the impact of providing information about the health consequences of eating meat and measuring attitudes, there was evidence that the intervention led to or was associated with more favourable attitudes towards eating less meat [33,34,35, 37]. Two out of four interventions providing information on the environmental impact of meat consumption led to or were associated with more favourable attitudes towards eating less meat [33, 35, 39]. One non-tailored educational intervention focussing on animal welfare [35] and another focussing on social antecedents of meat consumption were associated with less favourable attitudes towards meat consumption [42]. Conversely, none of the eight tailored educational interventions or five non-tailored interventions focussing on multiple consequences of meat consumption were found to influence attitudes [34, 43].

Secondary biological outcomes

The only biomarker of health on which studies reported was weight. Of four studies (N = 1 CT, N = 3 pre-post) evaluating the impact of lifestyle counselling interventions on weight [27,28,29,30] only one intervention, which explicitly focussed on weight management, was associated with a significant reduction in BMI in a pre-post comparison [29].

Discussion

Evidence from experimental intervention studies suggests that some interventions targeting conscious determinants of human behaviour could contribute towards reducing the demand for meat. Six lifestyle counselling interventions designed to reduce red and processed meat consumption led to [25, 26] or were associated with reduced meat consumption [27,28,29,30]. Evidence from RCTs suggested that two self-monitoring interventions reduced red [31] or processed meat consumption [32] during the intervention period and enhanced intentions to not exceed recommended levels of consumption. Providing non-tailored information on the health, or environmental, or socio-political, or animal welfare consequences of eating meat was associated with reduced intended consumption and virtual selection of meat in 16 out of 17 interventions [33,34,35,36,37, 39,40,41,42]. However, there was no evidence that any of six such interventions influenced actual behaviour [34, 37, 41, 42]. Only four of 14 interventions providing information about multiple consequences of eating meat were associated with reductions in meat consumption, purchases, or selection [34, 43,44,45,46,47]. None of the ten tailored educational interventions or of the four interventions implicitly highlighting animal welfare issues was found to reduce actual [44] or intended meat consumption [43, 49]. Participants’ attitudes towards eating (less) meat generally mirrored their intentions to do so. There was no robust evidence pertaining to any of the other secondary psychosocial outcomes or biomarkers of health risk.

Strengths and limitations

In this systematic review we employed gold standard methods striving to achieve robust and unbiased results. The scope of our review was kept broad to allow capturing a wide range of intervention approaches, which is important to inform this novel field of research. However, the results should be interpreted in the context of limitations of this review and of the studies included, most of which were of medium or low methodological quality. Having employed extensive methods to identify literature beyond the databases searches, over 40% of the papers included were unpublished records. This potentially prevented publication bias affecting the review unduly, but it also increased the proportion of studies with methodological limitations. Given this field is developing, we elected to include non-randomised studies, which increases the risk of bias in the findings. Additionally, the main outcome measures of this review presented challenges, with self-reported measures of consumption being prone to bias [50], food selection in virtual settings potentially lacking external validity [51, 52], and behavioural intentions being only moderately related to future behaviour [53]. Most studies only measured outcomes during or shortly after the intervention, so conclusions cannot be drawn on lasting effects. Many interventions were either underpowered, making potentially effective interventions difficult to detect, or were evaluated in non-randomised designs, precluding direct causal inference of effectiveness. Future studies should employ well-powered RCTs with longer follow-up to allow for causal inferences to be drawn on the interventions’ effectiveness and to better understand their longer term impact. The studies reviewed included predominantly white and well-educated volunteers, limiting the generalizability of the data to other population groups. Particular caution should be exercised when interpreting results of lifestyle counselling, as our search algorithm might have failed to identify all such interventions. Titles and abstracts of these studies often referred to ‘multiple health behaviours’ as the intervention target, and it is possible that papers specifically mentioning ‘meat consumption’, and therefore identified by our search algorithm, were more likely to be those finding significant results for this outcome. None of the interventions directly targeted gender-related barriers to reduce the demand for meat. Considering the importance of gender as a determinant of meat consumption, future studies should explore whether interventions targeting gender-related barriers can effectively reduce the demand for meat. In the absence of a taxonomy to classify different interventions targeting conscious determinants of human behaviour we grouped interventions according to some of their key behavioural strategies and implementation features. Our synthesis was partly based on an exploratory crisp-set QCA, which represents a sophisticated technique to descriptively identify patterns within data, but not to infer causality of effects. In particular, combinations associated with no evidence of effectiveness should not be thought as ‘ineffective’, as ‘absence of evidence does not equal evidence of absence’ [54]. Similarly, since we did not exclusively include RCTs, combinations associated with effectiveness do not necessarily support an underlying causal mechanism. It must also be considered that QCA did not differentiate between studies of different quality and size. Finally, while the quality assessment tool employed in this review allowed assessing different study designs, caution must be exercised when comparing quality scores between different study designs.

Findings in the context of existing evidence

The results of this review were consistent with past research on behaviour change interventions targeting other health behaviours. Lifestyle counselling and self-monitoring interventions have previously emerged as promising approaches to change different eating behaviours [55,56,57]. However, the resources needed to implement lifestyle counselling pose a barrier to its scalability. Moreover, existing evidence on lifestyle counselling targeting the general population rather than people suffering from ill-health is less clear [55], suggesting that our findings on lifestyle counselling may not apply to the general population. Educational interventions providing rational reasons for eating less meat may have underpinned the observed changes in conscious intentions. Nevertheless, unconscious psychosocial and environmental cues that influence behaviour in real-life settings [20, 58] may have prevented these effects from translating into actual behaviour outside experimental settings. Interventions targeting unconscious determinants of human behaviour [20, 58, 59] may therefore play an important role to help overcome this intention-behaviour gap. We plan to review the effectiveness of these approaches elsewhere [60]. The non-significant findings on tailored education are in contrast with the literature highlighting the importance of tailoring information [61, 62]. Nevertheless our findings were based on only two papers that found no evidence of effectiveness for any of the interventions they tested, regardless of tailoring [43, 44]. It is therefore possible, that intervention characteristics other than tailoring or methodological limitations of the aforementioned studies contributed to these non-significant results. However, it is also possible that individuals do not substantially benefit from receiving information about issues that they already value as important consequences of meat consumption, as these arguments might have naturally exhausted their potential for prompting behavioural change. Finally, while providing information was not found to directly influence behaviour, future research should explore whether this approach might contribute towards reducing population-wide demand for meat in other ways. For example, providing information on the benefits of eating less meat might increase the public’s acceptability for more structural interventions to reduce meat consumption.

Conclusion

This review is the first systematic synthesis of evidence about the effectiveness of interventions targeting conscious determinants of human behaviour to reduce the demand for meat. Some interventions targeting conscious determinants of human behaviour have the potential to reduce the demand for meat. In particular, self-monitoring and individual lifestyle counselling interventions showed promise in reducing actual consumption of meat. Education about health, environmental, socio-political, or animal welfare consequences of eating meat can reduce intended meat consumption and selection of meat in virtual environments, but there was little evidence on whether this approach influenced actual behaviour and the few studies examining this found no evidence that it did. Interventions providing information on several consequences of meat consumption, those implicitly highlighting animal suffering in the context of meat production or consumption, and those providing tailored information offered less promise. While the impact of interventions targeting conscious determinants of human behaviour was modest, if delivered at scale these interventions could contribute towards reducing the demand for meat at population-level.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CT:

-

Controlled trial

- QCA:

-

Qualitative Comparative Analysis

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial

References

Bechthold A, Boeing H, Schwedhelm C, Hoffmann G, Knüppel S, Iqbal K, et al. Food groups and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke and heart failure: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017:1–20 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29039970. Cited 9 Nov 2017.

Micha R, Wallace SK, Mozaffarian D. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of incident coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2010;121(21):2271–83 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20479151. Cited 23 May 2017.

Micha R, Michas G, Mozaffarian D. Unprocessed red and processed meats and risk of coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes – an updated review of the evidence. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2012;14(6):515–24 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23001745. Cited 23 May 2017.

Feskens EJM, Sluik D, van Woudenbergh GJ. Meat consumption, diabetes, and its complications. Curr Diab Rep. 2013;13(2):298–306 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23354681. Cited 9 Nov 2017.

Barnard N, Levin S, Trapp C. Meat consumption as a risk factor for type 2 diabetes. Nutrients. 2014;6(2):897–910 Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24566443. Cited 9 Nov 2017.

Bouvard V, Loomis D, Guyton KZ, Grosse Y, El Ghissassi F, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, et al. Carcinogenicity of consumption of red and processed meat. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(16):1599–600 Elsevier. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1470204515004441. Cited 9 Nov 2017.

Chan DSM, Lau R, Aune D, Vieira R, Greenwood DC, Kampman E, et al. Red and processed meat and colorectal cancer incidence: meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20456 Public Library of Science. Available from: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0020456. Cited 26 Oct 2015.

Parkin DM, Boyd L, Walker LC. 16. The fraction of cancer attributable to lifestyle and environmental factors in the UK in 2010. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(Suppl 2):S77–81 Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3252065&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. Cited 30 Oct 2014.

Steinfeld H, Gerber P, Wassenaar T, Castel V, Rosales M, De Haan C. Livestock’s long shadow. FAO, Rome. 2006;2006. http://www.fao.org/3/a-a0701e.pdf.

Tilman D, Clark M. Global diets link environmental sustainability and human health. Nature 2014;515(7528):518–522. Nature Publishing Group, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited. All Rights Reserved. Available from: doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13959. Cited 27 Jul 2015.

Pimentel D, Pimentel M. Sustainability of meat-based and plant-based diets and the environment. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(3 Suppl):660S–3S American Society for Nutrition. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12936963. Cited 23 May 2017.

Watts N, Amann M, Ayeb-Karlsson S, Belesova K, Bouley T, Boykoff M, et al. The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: from 25 years of inaction to a global transformation for public health. Lancet. 2017; Elsevier. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673617324649?_rdoc=1&_fmt=high&_origin=gateway&_docanchor=&md5=b8429449ccfc9c30159a5f9aeaa92ffb. Cited 25 Jan 2018.

Mcmichael AJ, Campbell-Lendrum DH, Corvalán CF, Ebi KL, Githeko AK, Scheraga JD, et al. Climate change and human health. Risks and responses. 2003. Available from: http://www.who.int/globalchange/publications/climchange.pdf. Cited 25 Jan 2018.

Economou V, Gousia P. Agriculture and food animals as a source of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria. Infect Drug Resist. 2015;8:49–61 Dove Press. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25878509. Cited 25 Jan 2018.

Garnett T, Mathewson S, Angelides P, Borthwick F. Policies and actions to shift eating patterns: what works? 2015. Available from: http://www.fcrn.org.uk/sites/default/files/fcrn_chatham_house_0.pdf. Cited 24 May 2017.

Bailey R, Froggatt A, Wellesley L. Livestock–climate change’s forgotten sector. 2014. Available from: https://www.chathamhouse.org/publication/livestock-climate-change-forgotten-sector-global-public-opinion-meat-and-dairy.

Wellesley L, Happer C, Froggatt A. Chatham house report changing climate, changing diets pathways to lower meat consumption. 2015 Available from: https://www.chathamhouse.org/publication/changing-climate-changing-diets.

Diepeveen S, Ling T, Suhrcke M, Roland M, Marteau TM. Public acceptability of government intervention to change health-related behaviours: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):756 BioMed Central. Available from: http://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-13-756. Cited 27 Nov 2017.

Jung JY, Mellers BA. American attitudes toward nudges. Judgm Decis Mak. 2016;11(1):62–75 Society for Judgment and Decision Making. Available from: http://journal.sjdm.org/15/15824a/jdm15824a.pdf.

Marteau TM. Towards environmentally sustainable human behaviour: targeting non-conscious and conscious processes for effective and acceptable policies. Philos Trans R Soc A Math Eng Sci. 2017;375(2095):20160371 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28461435. Cited 27 Nov 2017.

Bianchi F, Garnett E, Dorsel C, Paul A, Jebb S. Effectiveness of educational and motivational interventions to reduce the consumption, purchase, or selection of meat products: protocol for a systematic review with narrative synthesis. 2017. Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=76720. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Stansfield C, Dickson K, Bangpan M. Exploring issues in the conduct of website searching and other online sources for systematic reviews: how can we be systematic? Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):191 Available from: http://systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13643-016-0371-9. Cited 1 Sept 2017.

Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, Biondo PD, Cummings GG. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(1):12–8 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20698919. Cited 25 Feb 2015.

Thomas J, O’Mara-Eves A, Brunton G. Using qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) in systematic reviews of complex interventions: a worked example. Syst Rev. 2014;3(1):67 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24950727. Cited 1 Sept 2017.

Emmons KM, McBride CM, Puleo E, Pollak KI, Clipp E, Kuntz K, et al. Project PREVENT: a randomized trial to reduce multiple behavioral risk factors for colon cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(6):1453–9 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15941955. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Emmons KM, Stoddard AM, Fletcher R, Gutheil C, Suarez EG, Lobb R, et al. Cancer prevention among working class, multiethnic adults: results of the healthy directions–health centers study. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(7):1200–5 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15933240. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Schiavon CC, Vieira FGK, Ceccatto V, de Liz S, Cardoso AL, Sabel C, et al. Nutrition education intervention for women with breast cancer: effect on nutritional factors and oxidative stress. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2015;47(1):2–9 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25528078. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Hawkes AL, Gollschewski S, Lynch BM, Chambers S. A telephone-delivered lifestyle intervention for colorectal cancer survivors ‘CanChange’: a pilot study. Psychooncology. 2009;18(4):449–55 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19241477. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Hawkes AL, Patrao TA, Green A, Aitken JF. CanPrevent: a telephone-delivered intervention to reduce multiple behavioural risk factors for colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2012;12(1):560 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23181756. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Grimmett C, Simon A, Lawson V, Wardle J. Diet and physical activity intervention in colorectal cancer survivors: a feasibility study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19(1):1–6 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25245710. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Carfora V, Caso D, Conner M. Correlational study and randomised controlled trial for understanding and changing red meat consumption: the role of eating identities. Soc Sci Med. 2017;175:244–52 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28129949. Cited 24 May 2017.

Carfora V, Caso D, Conner M. Randomised controlled trial of a text messaging intervention for reducing processed meat consumption: the mediating roles of anticipated regret and intention. Appetite. 2017;117:152–60 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28651971. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Fehrenbach KS. The health and environmental impacts of meat consumption: using the extended parallel process model to persuade college students to eat less meat. 2013.

Berndsen M, van der Pligt J. Risks of meat: the relative impact of cognitive, affective and moral concerns. Appetite. 2005;44(2):195–205 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15808894. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Scrimgeour LR. Digital Persuasion: Effects of web-based information and beliefs on meat consumption attitudes and intentions. Psychology. 2012; University of Canterbury. Available from: https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/handle/10092/7427. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Cordts A, Nitzko S, Spiller A, Cordts A, Nitzko S, Spiller A. Consumer response to negative information on meat consumption in Germany. Int Food Agribus Manag Rev. 2014;17(A) International Food and Agribusiness Management Association (IFAMA). Available from: https://www.ifama.org/resources/Documents/v17ia/Cordts-Spiller-Nitzko.pdf.

Fehrenbach KS. Designing messages to reduce meat consumption: a test of the extended parallel process model: Arizona State University; 2015. Available from: https://repository.asu.edu/items/34852. Cited 28 Nov 2017

Bertolotti M, Chirchiglia G, Catellani P. Promoting change in meat consumption among the elderly: factual and prefactual framing of health and well-being. Appetite. 2016;106:37–47 Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195666316300782. Cited 24 May 2017.

Graham T, Abrahamse W. Communicating the climate impacts of meat consumption: the effect of values and message framing. Glob Environ Chang. 2017;44:98–108 Pergamon. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959378017303564. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Vibhuti P. Rainforest, reef, and our appetite for beef: communication for sustainable behaviour change. University of Otago; 2017. Available from: https://ourarchive.otago.ac.nz/handle/10523/7581. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Godfrey DM. Communicating sustainable food: connecting scientific information to consumer action: University of Calgary; 2014. Available from: http://theses.ucalgary.ca/handle/11023/1598. Cited 28 Nov 2017

Allen MW, Baines S. Manipulating the symbolic meaning of meat to encourage greater acceptance of fruits and vegetables and less proclivity for red and white meat. Appetite. 2002;38(2):118–30 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12027371. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Schnabelrauch Arndt CA. Tailoring feedback and messages to encourage meat consumption reduction: Kansas State University; 2016. Available from: http://krex.k-state.edu/dspace/handle/2097/32159. Cited 28 Nov 2017

Klöckner CA, Ofstad SP. Tailored information helps people progress towards reducing their beef consumption. J Environ Psychol. 2017;50:24–36 Academic Press. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0272494417300063. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Loy LS, Wieber F, Gollwitzer PM, Oettingen G. Supporting sustainable food consumption: mental contrasting with implementation intentions (MCII) aligns intentions and behavior. Front Psychol. 2016;7:607 Frontiers Media SA. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27199840. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Marette S, Millet G. Can information about health and environment beef up the demand for meat alternatives? 2016. METRICS, Model FORESIGHT Eur Sustain FOOD Nutr Secur – SUSFANS. Available from: http://susfans.eu/system/files/public_files/Publications/working_paper/SUSFANS_WP_Can_Information__Health_Environment_Beef_Up_the_Demand_Meat_Alternatives.pdf. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Leidig R. Sodexo meatless monday survey results. 2012. Available from: http://www.meatlessmonday.com/images/photos/2013/01/Sodexo-F.pdf. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Heal Promot. 1997;12(1):38–48 SAGE PublicationsSage CA: Los Angeles, CA. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38. Cited 13 Sept 2018.

Tian Q, Hilton D, Becker M. Confronting the meat paradox in different cultural contexts: reactions among Chinese and French participants. Appetite. 2016;96:187–94 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26368579. Cited 13 Dec 2017.

Schoeller DA, Thomas D, Archer E, Heymsfield SB, Blair SN, Goran MI, et al. Self-report–based estimates of energy intake offer an inadequate basis for scientific conclusions. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(6):1413–5 Oxford University Press. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/97/6/1413/4576934. Cited 13 Feb 2018.

Forwood SE, Ahern AL, Marteau TM, Jebb SA. Offering within-category food swaps to reduce energy density of food purchases: a study using an experimental online supermarket. 2015. Available from: https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12966-015-0241-1?site=ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Hartmann-Boyce J, Bianchi F, Piernas C, Riches SP, Frie K, Nourse R, Jebb SA. Grocery store interventions to change food purchasing behaviors: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;107(6):1004–16. https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/107/6/1004/5032657.

French DP, Cooke R, Mclean N, Williams M, Sutton S. What Do People Think about When They Answer Theory of Planned Behaviour Questionnaires? J Health Psychol. 2007;12(4):672–87 Sage Publications Sage UK: London, England. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1359105307078174. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Jaykaran, Saxena D, Yadav P, Kantharia ND. Nonsignificant P values cannot prove null hypothesis: absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2011;3(3):465–6 Wolters Kluwer -- Medknow Publications. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21966174. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Pomerleau J, Lock K, Knai C, McKee M. Interventions designed to increase adult fruit and vegetable intake can be effective: a systematic review of the literature. J Nutr. 2005;135(10):2486–95 American Society for Nutrition. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16177217. Cited 12 Dec 2017.

Semper HM, Povey R, Clark-Carter D. A systematic review of the effectiveness of smartphone applications that encourage dietary self-regulatory strategies for weight loss in overweight and obese adults. Obes Rev. 2016;17(9):895–906 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27192162. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Flores Mateo G, Granado-Font E, Ferré-Grau C, Montaña-Carreras X. Mobile phone apps to promote weight loss and increase physical activity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(11):e253 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26554314. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Hollands GJ, Marteau TM, Fletcher PC. Non-conscious processes in changing health-related behaviour: a conceptual analysis and framework. Health Psychol Rev. 2016;10(4):381–94 Routledge. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17437199.2015.1138093. Cited 27 Nov 2017.

Marteau TM, Hollands GJ, Fletcher PC. Changing human behavior to prevent disease: the importance of targeting automatic processes. Science. 2012;337(6101):1492–5 Available from: http://www.sciencemag.org/content/337/6101/1492. Cited 27 Dec 2015.

Bianchi F, Garnett E, Dorsel C, Aveyard P, Jebb SA. Restructuring physical micro-environments to reduce the demand for meat: a systematic review and qualitative comparative analysis. The Lancet Planetary Health. 2018;2(9):e384–97. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2542519618301888?via%3Dihub.

Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(4):673–93 Available from: http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.673. Cited 28 Nov 2017.

Whatnall MC, Patterson AJ, Ashton LM, Hutchesson MJ. Effectiveness of brief nutrition interventions on dietary behaviours in adults: a systematic review. Appetite. 2018;120:335–47 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28947184. Cited 12 Dec 2017.

Acknowledgements

This research is part of the Wellcome Trust, Our Planet Our Health programme (Livestock, Environment and People - LEAP), award number 205212/Z/16/Z. We thank Nia Roberts for helping with designing and conducting the searches. We thank Brian Cook for providing useful feedback on previous versions of this paper. We thank the authors who sent us further information about their studies.

Funding

FB’s time on this project is funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC), Green Templeton College Oxford, and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research (SPCR). CD’s time on this project is funded by the Wellcome Trust (LEAP – Livestock Environment And People). EG’s time on this project is funded by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC). PA and SJ are supported by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) and the Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care Oxford at Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust (CLAHRC).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors designed research; FB, CD, and EG conducted research; FB, SAJ, and PA analysed data; FB led the writing of the paper; FB had primary responsibility for the final content. All authors read, edited and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

N/A.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Database search strategy. Algorithm used to search the databases (example for MEDLINE) and list of databases searched. Table S2. Searches conducted in publicly accessible online resources. Table S3. Interventions’ impact on or association with the demand for meat at the longest follow-up. Table S4. Interventions’ impact on or association with attitudes, perceived behavioural control, and subjective social norms of eating meat at both follow-up. Table S5. Interventions’ impact on or association with biomarkers of heath risk at both follow-up. (DOCX 61 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bianchi, F., Dorsel, C., Garnett, E. et al. Interventions targeting conscious determinants of human behaviour to reduce the demand for meat: a systematic review with qualitative comparative analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 15, 102 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0729-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0729-6