Abstract

Background

To identify whether changes in adult health and social factors are associated with simultaneous changes in inactivity.

Methods

Health, social factors and leisure-time inactivity (activity frequency < 1/week) were self-reported at 33y and 50y in the 1958 British birth cohort (N = 12,271). Baseline (33y) health and social factors and also patterns of change in factors 33y-to-50y were related to inactivity 33y-to-50y (never inactive, persistently inactive, deteriorating to inactivity, or improving from inactivity) using multinomial logistic regression.

Results

Approximately 31% were inactive at 33y and 50y; 35% changed status 33y-to-50y (17% deteriorating to inactivity, 18% improving from inactivity). Baseline poor health and obesity were associated with subsequent (33y-to-50y) inactivity; e.g. for poor health, relative risk ratios (RRRs) for deteriorating to inactivity (vs never inactive) and improving from inactivity (vs persistently inactive) were 1.38(1.16,1.64) and 0.77(0.63,0.94) respectively. Adverse changes in health and weight were associated with simultaneous adverse changes in inactivity; e.g. worsening health (vs always good/excellent health) was associated with higher risk of deteriorating to inactivity (RRR:2.20(1.85,2.62)) and lower risk of improving from inactivity (RRR:0.61(0.49,0.77)). However, improving health and weight loss were not associated with improving from inactivity. Worsening self-efficacy 33y-to-50y was associated with lower risk of improving from inactivity; there was no association between improving self-efficacy and inactivity change. Downward social mobility was not associated with deteriorating to or improving from inactivity. Changes in depression symptom level, marriage/co-habitation or parenthood 33y-to-50y were not associated with inactivity changes. No associations were observed for employment.

Conclusions

Associated changes in mid-life health factors with deleterious inactivity changes, highlight the importance of maintaining health, weight and self-efficacy across adulthood to deter inactivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the UK, 44% of adults never do any moderate intensity physical activity [1] and globally, 23% are inactive [2] (i.e. do not meet physical activity recommendations). The latter is of concern because inactivity has high health and economic burdens [3,4,5]; inactivity prevention is therefore an important public health goal [6]. However, knowledge gaps relating to inactivity need addressing, and one such gap concerns influences on changes in inactivity behaviours. Physical inactivity tracks at low to moderate levels in adulthood [7], and understanding is needed on why some people continue to have a stable behaviour (i.e. be physically active or inactive over time) or why their behaviour changes (i.e. deteriorates to or improves from inactivity). Such knowledge would contribute evidence relevant to the planning of public health interventions.

Several correlates of physical inactivity have been identified [8] and studies have examined circumstances at baseline with inactivity several years later [9, 10]. However, while some longitudinal studies have examined concurrent influences on inactivity [11, 12], with few exceptions [13], the impact of change in factors on inactivity patterns is unclear. Likely influences on inactivity include poor health [9], adiposity [14], depression [15], low self-efficacy [16] and social factors such as socio-economic position (SEP) [17] and parenthood [18]. Physical factors (e.g. poor health and adiposity) could hinder activity via dyspnea [14] or other functional limitations. Factors related to mental functioning (e.g. depression and low self-efficacy) could operate via outcome expectations; e.g. low self-efficacy may reduce expectations about what physical activity will achieve [16]. Social factors (e.g. manual SEP) could limit the availability of, or a person’s response to, opportunities for activity [19]. Such health and social factors are dynamic and subject to change as individuals’ age, yet, these changes are usually ignored. To illustrate, relationships between poor health and subsequent inactivity have been examined [9], but little attention has been given to simultaneous changes in health and inactivity. Patterns over time are important to consider, because when a factor remains largely stable, examining associations between the factor at baseline with change in inactivity could potentially lead to null findings [20]; e.g. change in SEP may be more relevant to inactivity change than stable SEP. Thus, acknowledging the limited available evidence, calls have been made for longitudinal studies to assess the impact of changes in factors on changes in physical inactivity [10, 20, 21].

Therefore, using a nationwide general population sample, we aimed to identify associations of potential contemporary health (poor health, adiposity, depression, low self-efficacy) and social (manual SEP, not in paid employment, marriage/co-habitation, parenthood) factors with adult leisure-time inactivity. Specific objectives were to examine associations of (i) baseline factors at 33y with subsequent inactivity 33y-to-50y and (ii) patterns of change in factors 33y-to-50y with inactivity over the same ages. Previous work by ourselves [7] and others [17, 22] suggests that research on adult inactivity should consider influences on inactivity from earlier life-stages, hence we assessed whether associations remained after taking account of early-life factors. Given the lack of a consistent definition, we, like others [23,24,25,26], defined inactivity as activity frequency < 1/week, which is associated with increased risk of unfavourable outcomes [24,25,26], including mortality [24, 25].

Methods

The 1958 British Birth Cohort is an ongoing longitudinal study of all born during one week in March 1958 across England, Scotland and Wales (N = 17,638) and a further 920 immigrants with the same birth week [27]. Information was collected in childhood (birth, 7, 11 and 16y) and adulthood (23, 33, 42, 45 and 50y). Ethical approval was given, including at 50y by the London Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee; informed consent was obtained from participants at various ages. Respondents in mid-adulthood are broadly representative of the surviving cohort [28]; this study consists of those living in Britain at 50y with information on inactivity at either 33y or 50y (N = 12,271).

Physical inactivity at 33y and 50y was ascertained using the same questions, asking participants about regular leisure-time activity frequency. In the questionnaire, ‘regular’ was defined as ≥1/month for most of the year and, to aid recall, a list of example activities (of predominantly moderate or vigorous intensity [29] e.g. swimming, walking) was provided. Those responding affirmatively, reported activity frequency from every/most days to < 2–3 times/month [29]. In this manuscript we define low activity frequency as < 1/week (i.e. those reporting activity as < 2–3 times/month and those reporting no ‘regular’ activity), hereafter referred to as inactivity. Cross-classifying binary measures at 33y and 50y gave two stable behaviour groups: ‘never inactive’ (active ≥1/week at both ages) and ‘persistently inactive’ (< 1/week at both ages); and two behaviour change groups: ‘deteriorating to inactivity’ (≥1/week at 33y, < 1/week at 50y) and ‘improving from inactivity’ (< 1/week at 33y, ≥1/week at 50y).

Health and social factors at 33y and 50y: include poor self-rated heath, adiposity, depression, low self-efficacy, manual SEP, not in paid employment, not married/co-habiting and parenthood at ≥2 children. Factors were identified from previous studies [8, 20], assessed prospectively at 33y and 50y, and, as in previous research [30], categorised as binary variables (details in Table 1). Similar to physical inactivity patterns 33y-to-50y, we identified two stable and two change groups 33y-to-50y, e.g. for SEP: always non-manual class, always manual class (i.e. stable groups) and upwardly mobile from manual to non-manual and downwardly mobile from non-manual to manual (i.e. change groups). For adiposity, we used obesity in analysis of baseline (33y) factors with subsequent inactivity 33y-to-50y; for analyses of simultaneous changes with inactivity 33y-to-50y we examined weight.

Covariates were identified from previous work [7] and recorded prospectively at birth (SEP), age 7y (pre-pubertal stature) and 16y (cognitive ability, parental education) or at multiple ages in childhood (hand control/co-ordination problems, household amenities) (details in Table 1).

Statistical analysis

As a preliminary step, to identify factors for main analyses, we examined simple associations between factors and inactivity. These preliminary analyses assessed associations between each factor and inactivity concurrently for ages 33y and 50y separately (i.e. cross-sectionally) and for 33y factors with 50y inactivity. We then adjusted associations for all other factors at the same age. Any factor that was unrelated to inactivity at both 33 and 50y was excluded from further analyses; all other factors were included.

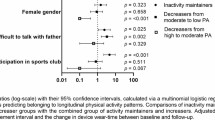

In main analyses to examine associations of factors at baseline (33y) with inactivity 33y-to-50y (objective i), we fit two multinomial logistic regression models, which provided Relative Risk Ratios (RRRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). First, we compared persistently vs never inactive (i.e. most vs. least adverse behaviour) and deteriorating to inactivity vs never inactive (i.e. changing vs. remaining the same). Second, we compared improving from inactivity vs persistent inactivity. We then examined associations of factors 33y-to-50y and the four inactivity patterns over the same ages (objective ii), again using multinomial logistic regression. For these main analyses, gender differences in associations with inactivity were tested using an interaction term (gender*factor); there was little evidence of effect modification (Tables 2 and 3, footnotes), hence results are presented for genders combined. All associations were mutually adjusted for all other factors at the same life-stage, and then adjusted for early-life covariates.

We conducted sensitivity analyses to account for potential bi-directional associations of inactivity with adiposity or mental health [14, 15, 31, 32] and to control for previous activity level; i.e. we adjusted for 16y BMI and mental health and 23y activity.

To minimize data loss multiple imputation via chained equations was used to impute missing data on inactivity (11% at 33y; 21% at 50y), health and social factors (10% (33y marriage/co-habitation) to 24% (50y SEP)) and covariates (2% (16y cognition) to 30% (16y BMI)). Imputation models included all model variables, including previously identified key predictors of missingness (16y externalising and internalising behaviours, cognitive ability, and pre-pubertal stature) [28]. Regression analyses were run across 20 imputed datasets; overall estimates were attained using Rubin’s rules. Imputed results (presented here) were broadly similar to those using observed values.

Results

A third of the population were inactive at 33y and 50y; between these ages, 35% changed their inactivity status with 17% deteriorating to inactivity and 18% improving from inactivity (Table 2, footnotes). Likewise, in this population, there were changes in health and social factors over the same ages; e.g. prevalence of poor health increased from 14 to 19% (Additional file 1: Table S1) with 13% worsening and 7% improving from poor health (Table 3). In preliminary analyses, most 33y and 50y health and social factors were associated with inactivity at either 33y or 50y (Additional file 1: Table S1) and therefore included in main analyses; an exception was not in paid employment, which was not analysed further.

Baseline factors (33y) and inactivity 33y-to-50y

Poor health and obesity were associated with deteriorating to and improving from inactivity (Table 2); e.g. for poor health, RRRsadjusted were 1.38(1.16,1.64) and 0.77(0.63,0.94) respectively. Low self-efficacy and manual SEP were associated with deteriorating to inactivity but not improving from inactivity. Baseline (33y) poor health, obesity, depression, low self-efficacy and manual SEP were all associated with persistent inactivity. Partnership and parenthood were not associated with inactivity patterns 33y-to-50y. Further adjustment for early-life factors attenuated associations, but most remained (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Health and social factors 33y-to-50y and inactivity 33y-to-50y

Worsening (vs always good) health 33y-to-50y was associated with higher risk of deteriorating to inactivity 33y-to-50y (RRRadjusted:2.20(1.85,2.62)) and with lower risk of improving from inactivity (RRRadjusted:0.61(0.49,0.77); Table 3). However, improving health was also associated with deteriorating to inactivity (RRRadjusted:1.30(1.04,1.62)) but not with improving from inactivity. Weight gain was associated with higher risk of deteriorating to inactivity (RRRadjusted:1.26(1.09,1.45)) and lower risk of improving from inactivity (RRRadjusted:0.82(0.68,0.98)); there were no associations between weight loss and change in inactivity. Worsening self-efficacy was associated with a lower risk of improving from inactivity (RRRadjusted:0.77(0.61,0.97)); with a borderline association for deteriorating to inactivity. Downward social mobility was not associated with change in inactivity, but upward mobility was associated with higher risk of deteriorating to inactivity (RRRadjusted:1.26(1.05,1.51)). Remaining in poor health, low self-efficacy and manual SEP 33-to-50y were associated with elevated risk of deteriorating to inactivity (RRRsadjusted ranged from 1.39 to 2.04) and, for all except manual SEP 33y-to-50y, with lower risk of improving from inactivity (RRRsadjusted ranged from 0.55 to 0.73). Remaining in poor health, low self-efficacy and manual SEP 33-to-50y were also associated with elevated risk of inactivity persistence (RRRadjusted ranged from 1.49 to 3.16). Adjustment for early-life factors attenuated associations, but most remained (Table 3 vs Additional file 1: Table S3). In sensitivity analyses (to account for potential bi-directional associations of inactivity with adiposity or mental health, and to control for previous activity level) including further adjustment for 16y BMI and mental health and 23y activity, showed that most associations remained, although attenuated slightly (Table 3 vs Additional file 1: Table S4). Finally, no associations were observed for depression, partnerships and parenthood 33y-to-50y with inactivity over the same ages.

Discussion

In a general mid-life adult population, we found that poor-rated health and obesity at baseline (33y) were associated with subsequent change in inactivity 33y-to-50y. Moreover, changes in health and weight 33y-to-50y were associated with changes in inactivity over the same ages. To illustrate, worsening health (affecting 13% of the population) was associated with more than two-fold risk of deteriorating to inactivity and a 39% lower risk of improving from inactivity. Low self-efficacy at baseline was associated with subsequent deterioration to inactivity (but not improvement from inactivity), whereas worsening self-efficacy 33y-to-50y (affecting 12% of the population) was associated with a 23% lower risk of improving from inactivity. At baseline, manual SEP was associated with subsequent deterioration to inactivity (not with improvement from inactivity) but downward mobility 33y-to-50y was not associated with inactivity changes. As expected, we found that remaining in poor health, low self-efficacy and manual SEP 33-to-50y were associated with higher risk of inactivity persistence. Few associations were observed for depression, none of which were found for change in this factor. Finally, no associations were found for partnership or parenthood, for baseline or change measures. Employment status was unrelated to inactivity in mid-adulthood.

Study data are unique in respect of prospectively recording contemporary factors and inactivity at two ages almost 20y apart, with similar measures allowing examination of simultaneous changes. Also, several prospectively measured early-life covariates were available. Limitations are acknowledged. There is no consistent definition of inactivity; some studies use failure to meet recommended activity levels [3, 9], while others identify the least active in a population [33]. Our measure, based on self-reported infrequent leisure-time activity (< 1/week), is similar to that used by others [23,24,25,26], and has been found to be associated with mortality [24, 25]. However, misclassification of an individual’s inactivity status and corresponding pattern over time remains a possibility. Regarding health and social factors, our measures were extensive but not exhaustive, e.g. we could not consider changes in neighbourhood or intention to participate in activity, which may be important [34, 35]. For the considered factors and inactivity, the timing of transitions are unknown; e.g. some changes may have occurred immediately after 33y, whereas others may have been just before 50y. The study is observational and uncontrolled covariates, measurement error or bi-directional associations (e.g. with adiposity or mental health [14, 15, 31, 32]) cannot be excluded. However, adjustment for prior adiposity, mental health and physical activity had little effect on results. As with any long-term study, sample attrition occurred, but we maximised available data by including participants with an inactivity measure at either 33y or 50y and avoided sample reductions due to missing information by using multiple imputation.

Comparison with other studies is hampered by heterogeneity in inactivity measurement and, with few exceptions [36, 37], previous studies have focused on changes over shorter periods (i.e. months to a few years) [20] than our study. However, some consistencies can be identified. Approximately a third of our population were inactive in mid-adulthood, which aligns with a global estimate of 31% [38]; and prevalence of persistent inactivity 33y-to-50y in our population (14%) is broadly consistent with others [39]. It is noteworthy that the prevalence of some (e.g. poor health), but not all (e.g. partnership) factors varied with age, but, like inactivity, most showed changes, e.g. approximately 21% changed partnership status 33y-to-50y.

Notwithstanding previous research by others [17, 22, 33] and ourselves [7, 30, 40] on life-course influences on inactivity, our focus here addresses an identified knowledge gap on simultaneous changes in factors and inactivity [10, 20, 21]. The ages examined (33y and 50y) span mid-adulthood; if physical activity is at a low level at this life-stage, it is not easily increased later on [41]. In turn, physical activity at older ages has benefits e.g. for the prevention of onset and delayed progression of disability [42]. Thus, inactivity in mid-adulthood becomes increasingly important against the backdrop of an ageing population [43].

A major study finding, is that poor health and obesity at baseline as well as worsening health and weight gain 33y-to-50y were associated with higher risk of deteriorating to and lower risk of improving from inactivity. Notably, associations were generally robust to adjustment for concurrent and early-life factors. Such findings agree with the scant literature available [37, 39], e.g. showing, as expected, associations of greater weight increases with persistent inactivity vs never inactive [39]. Importantly, there was no evidence to support an effect of improving health or weight loss on improving from inactivity, suggesting that the barriers to and promoters of activity may not be equivalent. Such novel findings highlight the need to continually maintain health and weight to deter adverse activity patterns; this need is particularly important at the life-stage examined, as mid-adulthood is generally a time of declining health [44] and increasing adiposity [45].

For self-efficacy and depressive symptoms, our study adds to a limited literature. Self-efficacy could influence inactivity e.g. by lessening an individual’s perceived capability to overcome barriers to activity [16] and, while our measure is general rather than specific to activity, we found that low self-efficacy at baseline was associated with a 19% higher risk of deteriorating to inactivity. This finding in our general population sample, agrees with previous work among employees [46]. Further support for differences in the barriers to and promoters of activity is our novel finding that worsening self-efficacy 33y-to-50y was associated with 23% lower risk of improving from inactivity, although, improving self-efficacy 33y-to-50y was not associated with improvement from inactivity. For depressive symptoms, the null associations for simultaneous changes with inactivity, agree with previous reports in this cohort [15] and elsewhere [47]. These results suggest that depressive symptom levels do not exert a major influence on inactivity behaviour, at least in populations approaching their 50’s. However, other aspects of mental functioning, such as affective judgments (i.e. enjoyment and pleasure from activity) may predict inactivity change [20].

To our knowledge, simultaneous changes in SEP and inactivity have not been examined previously. As might be expected, we found consistently manual SEP 33y-to-50y to be associated with higher risk (by 49%) of persistent inactivity. However, associations were less consistent for simultaneous changes in SEP and inactivity. Changes in SEP were not associated with improvement from inactivity, but surprisingly, upward mobility 33y-to-50y was associated with a higher risk of deteriorating to inactivity. Thus, our findings extend the literature that has thus far examined SEP and activity at a particular age [17, 22, 37]. For parenthood (number of children in the household), we found no association between baseline status and subsequent inactivity or between simultaneous changes in parenthood and inactivity. These findings differ from a review of eight studies, predominantly in women [20], identifying motherhood as a predictor of deteriorating to inactivity, and another study [13], reporting that becoming a parent was associated with corresponding decreases in activity. Differences between findings could be due to our inclusion of men and women, the ages or time-frames considered (e.g. median follow-up of 3 years in the review vs almost two decades in our study) or differences in study design including inactivity definitions. In sum, our findings suggest that, over the long-term, parenthood has little impact on inactivity. Finally, for partnership status and employment, our null results contrast with cross-sectional studies [48, 49], but are consistent with a review of 16 and 14 studies respectively suggesting no associations with inactivity change [20]. Such observations are important because they highlight the limitations of previous studies that do not consider within-person inactivity changes over time.

Conclusions

Longitudinal studies of factors related to inactivity change shed light on why some people initiate and maintain an active lifestyle and others do not. Our study adds new knowledge on likely contemporary influences on physical inactivity; it suggests that changes in inactivity status are not uncommon, and that health factors may be particularly important in relation to such changes. Associations for worsening of health factors with adverse inactivity changes did not always correspond to findings for improvement in health factors with improvement from inactivity. This finding, suggesting that barriers to activity may not be equivalent to promoters of activity, has implications for policies to encourage activity among the inactive [50]. Moreover, examining corresponding changes in factors and inactivity adds weight to our findings with regard to causality. Specifically, that mid-life poor health, weight gain and self-efficacy were associated with corresponding detrimental inactivity patterns. Findings highlight the importance of maintaining health, weight and self-efficacy across adulthood to deter adverse activity patterns. Several of these factors are relatively common, underscoring their potential importance for population levels of inactivity in mid-adulthood.

References

European Commission. Special Eurobarometer 412 sports and physical activity; 2014.

World Health Organization Global Health Observatory. Prevalence of insufficient physical activity.; Available from: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/physical_activity_text/en/. cited 17/05/2016

Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):219–29.

Ding D, Lawson KD, Kolbe-Alexander TL, et al. The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1311–24.

Pratt M, Norris J, Lobelo F, Roux L, Wang GJ. The cost of physical inactivity: moving into the 21st century. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(3):171–3.

Das P, Horton R. Physical activity-time to take it seriously and regularly. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1254–5.

Pinto Pereira SM, Li L, Power C. Early life factors and adult leisure time physical inactivity stability and change. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(9):1841–8.

Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, et al. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet. 2012;380(9838):258–71.

Picavet HS, Wendel-vos GC, Vreeken HL, Schuit AJ, Verschuren WM. How stable are physical activity habits among adults? The Doetinchem cohort study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(1):74–9.

Barnett TA, Gauvin L, Craig CL, Katzmarzyk PT. Distinct trajectories of leisure time physical activity and predictors of trajectory class membership: a 22 year cohort study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5:57.

Uijtdewilligen L, Peeters GM, van Uffelen JG, Twisk JW, Singh AS, Brown WJ. Determinants of physical activity in a cohort of young adult women. Who is at risk of inactive behaviour? J Sci Med Sport. 2015;18(1):49–55.

Uijtdewilligen L, Twisk JW, Chinapaw MJ, Koppes LL, Van Mechelen W, Singh AS. Longitudinal person-related determinants of physical activity in young adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46(3):529–36.

Bell S, Lee C. Emerging adulthood and patterns of physical activity among young Australian women. Int J Behav Med. 2005;12(4):227–35.

Golubic R, Ekelund U, Wijndaele K, et al. Rate of weight gain predicts change in physical activity levels: a longitudinal analysis of the EPIC-Norfolk cohort. Int J Obes. 2013;37(3):404–9.

Pinto Pereira SM, Geoffroy MC, Power C. Depressive symptoms and physical activity during 3 decades in adult life bidirectional associations in a prospective cohort study. JAMA Psychiat. 2014;71(12):1373–80.

White SM, Wojcicki TR, McAuley E. Social cognitive influences on physical activity behavior in middle-aged and older adults. J Gerontol B-Psychol. 2012;67(1):18–26.

Elhakeem A, Cooper R, Bann D, Hardy R. Childhood socioeconomic position and adult leisure-time physical activity: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:92.

Rhodes RE, Blanchard CM, Benoit C, et al. Physical activity and sedentary behavior across 12 months in cohort samples of couples without children, expecting their first child, and expecting their second child. J Behav Med. 2014;37(3):533–42.

Kuh D, Power C, Blane D, Bartley M. Socioeconomic pathways between childhood and adult health. In: Kuh D, B-S Y, editors. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. 2 ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. p. 371–98.

Rhodes RE, Quinlan A. Predictors of physical activity change among adults using observational designs. Sports Med. 2015;45(3):423–41.

Xue QL, Bandeen-Roche K, Mielenz TJ, et al. Patterns of 12-year change in physical activity levels in community-dwelling older women: can modest levels of physical activity help older women live longer? Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(6):534–43.

Juneau CE, Sullivan A, Dodgeon B, Cote S, Ploubidis GB, Potvin L. Social class across the life course and physical activity at age 34 years in the 1970 British birth cohort. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24(9):641–7.

Aarnio M, Winter T, Kujala U, Kaprio J. Associations of health related behaviour, social relationships, and health status with persistent physical activity and inactivity: a study of Finnish adolescent twins. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36(5):360–4.

Vatten LJ, Nilsen TI, Romundstad PR, Droyvold WB, Holmen J. Adiposity and physical activity as predictors of cardiovascular mortality. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006;13(6):909–15.

Brown RE, Riddell MC, Macpherson AK, Canning KL, Kuk JL. The association between frequency of physical activity and mortality risk across the adult age span. J Aging Health. 2013;25(5):803–14.

Hamer M, Stamatakis E, Steptoe A. Dose-response relationship between physical activity and mental health: the Scottish health survey. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(14):1111–4.

Power C, Elliott J. Cohort profile: 1958 British birth cohort (National Child Development Study). Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(1):34–41.

Atherton K, Fuller E, Shepherd P, Strachan DP, Power C. Loss and representativeness in a biomedical survey at age 45 years: 1958 British birth cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(3):216–23.

Parsons TJ, Power C, Manor O. Longitudinal physical activity and diet patterns in the 1958 British birth cohort. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(3):547–54.

Pinto Pereira SM, Li L, Power C. Lifetime risk factors for leisure-time physical inactivity in mid-adulthood. Prev Med Rep. 2018;11:23–30.

Richmond RC, Davey Smith G, Ness AR, den Hoed M, McMahon G, et al. Assessing causality in the association between child adiposity and physical activity levels: a Mendelian randomization analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11(3):e1001618. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001618

Petersen L, Schnohr P, Sorensen TIA. Longitudinal study of the long-term relation between physical activity and obesity in adults. Int J Obes. 2004;28(1):105–12.

Kuh DJ, Cooper C. Physical activity at 36 years: patterns and childhood predictors in a longitudinal study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1992;46(2):114–9.

Ranchod YK, Diez Roux AV, Evenson KR, Sanchez BN, Moore K. Longitudinal associations between neighborhood recreational facilities and change in recreational physical activity in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis, 2000-2007. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179(3):335–43.

Plotnikoff RC, Lubans DR, Trinh L, Craig CL. A 15-year longitudinal test of the theory of planned behaviour to predict physical activity in a randomized national sample of Canadian adults. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2012;13(5):521–7.

Kern ML, Reynolds CA, Friedman HS. Predictors of physical activity patterns across adulthood: a growth curve analysis. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 2010;36(8):1058–72.

Borodulin K, Makinen TE, Leino-Arjas P, et al. Leisure time physical activity in a 22-year follow-up among Finnish adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:121.

World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010; 2011.

Piirtola M, Kaprio J, Waller K, et al. Leisure-time physical inactivity and association with body mass index: a Finnish twin study with a 35-year follow-up. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(1):116–27.

Pinto Pereira SM, Power C. Early adulthood determinants of mid-life leisure-time physical inactivity stability and change: findings from a prospective birth cohort. J Sci Med Sport. 2018;21(7):720–26.

Hirvensalo M, Lintunen T. Life-course perspective for physical activity and sports participation. Eur Rev Aging Phys A. 2011;8(1):13–22.

Tak E, Kuiper R, Chorus A, Hopman-Rock M. Prevention of onset and progression of basic ADL disability by physical activity in community dwelling older adults: a meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(1):329–38.

Kontis V, Bennett JE, Mathers CD, Li GQ, Foreman K, Ezzati M. Future life expectancy in 35 industrialised countries: projections with a Bayesian model ensemble. Lancet. 2017;389(10076):1323–35.

Power C, Kuh D, Morton S. From developmental origins of adult disease to life course research on adult disease and aging: insights from birth cohort studies. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34:7–28.

Li L, Hardy R, Kuh D, Lo Conte R, Power C. Child-to-adult body mass index and height trajectories: a comparison of 2 British birth cohorts. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(9):1008–15.

Rhodes RE, Plotnikoff RC, Courneya KS. Predicting the physical activity intention-behavior profiles of adopters and maintainers using three social cognition models. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36(3):244–52.

Ku PW, Fox KR, Chen LJ, Chou P. Physical activity and depressive symptoms in older adults 11-year follow-up. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(4):355–62.

Pettee KK, Brach JS, Kriska AM, et al. Influence of marital status on physical activity levels among older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(3):541–6.

Van Domelen DR, Koster A, Caserotti P, et al. Employment and physical activity in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(2):136–45.

Cabinet Office London. Sporting future: a new strategy for an active nation; 2015.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Centre for Longitudinal Studies (CLS), UCL Institute of Education, for the use of these data and the UK Data Service for making them available. Neither CLS nor the UK Data Service bear any responsibility for the analysis or interpretation of these data.

Funding

This work was supported by the Department of Health Policy Research Programme through the Public Health Research Consortium (PHRC) and supported by the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust and University College London. SPP is funded by a UK Medical Research Council Career Development Award (ref: MR/P020372/1). The views expressed in the publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Health. Information about the wider programme of the PHRC is available from http://phrc.lshtm.ac.uk. The funders had no input into study design; data collection, analysis, and interpretation; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication. Researchers were independent of influence from study funders.

Availability of data and materials

Cohort data comply with ESRC data sharing policies, readers can access these data via the UK Data Archive at www.data-archive.ac.uk.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CP designed the study. SMPP did the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript with input from CP. Both authors have seen and approved the final version for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was given, including at 50y by the London Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee (ref 08/H0718/29); informed consent was obtained.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Prevalence of health and social factors at 33y and 50y and associations (ORs (95% CIs)) with physical inactivity at 33y or 50y. Table S2. Associations (RRRs (95% CIs)) between baseline health and social factors (33y) and physical inactivity 33y-to-50y. Table S3. Associations (RRRs (95% CIs)) between health and social factors (33y-to-50y) and physical inactivity 33y-to-50y. Table S4. Associations (RRRs (95% CIs)) between health and social factors (33y-to-50y) and physical inactivity 33y-to-50y (adjusted for additional covariates. (DOCX 33 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Pinto Pereira, S.M., Power, C. Change in health and social factors in mid-adulthood and corresponding changes in leisure-time physical inactivity in a prospective cohort. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 15, 89 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0723-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0723-z