Abstract

Background

Twenty to thirty percent of planned cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (CRS and HIPEC) procedures are abandoned intra-operatively. Pre-operative factors associated with unresectability identified previously were used to develop a Pre-Operative Predictive Score (PROPS), which was compared with current selection criteria—Peritoneal Surface Disease Severity Score (PSDSS), Verwaal’s Prognostic Score (PS) and Colorectal Peritoneal Metastases Prognostic Surgical Score (COMPASS), to determine which score provides the best prediction for unresectability.

Methods

Fifty-six patients with peritoneal metastases of colorectal origin were included. Beta-coefficient values of significant variables (p < 0.05) were determined from multivariate analysis to develop PROPS. PROPS, PSDSS, PS and COMPASS were compared using a receiver operating characteristic curve to calculate its accuracy, sensitivity and specificity.

Results

PROPS consisted of nine patient and tumour factors which were categorised into three groups: (i) poor tumour biology: previous inadequate resection, underwent multiple lines of chemotherapy and poorly differentiated or signet cell histology; (ii) heavy tumour burden: abdominal distension, palpable abdominal mass and computed tomography findings of ascites, small bowel disease and/or omental thickening; and (iii) active tumour proliferation: elevated tumour markers. Overall, PROPS achieved 86% accuracy with 100% sensitivity and 68% specificity, PSDSS achieved 85% accuracy with 100% sensitivity and 63% specificity, PS achieved 73% accuracy with 100% sensitivity and 68% specificity and COMPASS achieved 61% accuracy with 27% sensitivity and 100% specificity.

Conclusions

PROPS is more effective in predicting unresectability as compared to PSDSS, PS and COMPASS, and has the added advantage of using solely pre-operative factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

1.Introduction

Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) have been showed to increase survival in patients with colorectal cancer peritoneal metastases (pCRC) [1, 2]. A proportion of CRS and HIPEC cases are abandoned intra-operatively due to extensive disease (i.e. high peritoneal carcinomatosis index (PCI) score) resulting in unnecessary laparotomy [3,4,5]. A way to circumvent this is to identify the unresectable cases pre-operatively. Pre-operative radiological investigations alone fail to accurately predict PCI score accurately [6]. One can also extrapolate the factors founds in prognostic scores such as Peritoneal Surface Disease Severity Score (PSDSS), Verwaal Prognostic Score (PS) and Colorectal Peritoneal Metastases Prognostic Surgical Score (COMPASS) for pre-operative selection outlined in Table 1 [7,8,9]. However, these prognostic scoring systems were established from studies that only included patients with pCRC that underwent successful CRS and HIPEC (i.e. completeness of cytoreduction score of 0 or 1), and were designed to select patients for complete resection or improved survival. In addition, both scores include intra-operative factors in their scoring model. Therefore, these scores are not primed to predict for unresectability pre-operatively. We have published an earlier study on preoperative factors associated with unresectability included all tumour types [10]. For this study, we only selected patients with pCRC. The aim was to develop a Pre-Operative Predictive Score (PROPS) for unresectability in patients with pCRC, and compare it with the PSDSS and PS, to determine which score best predicts for unresectability.

2.Methods

This is a follow-up to a study that was conducted at the National Cancer Centre Singapore from April 2004 to May 2014 and was approved by the local Centralised Institutional Review Board. Data was retrospectively collected from a prospective CRS and HIPEC database of patients. Only patients with pCRC were included.

The patients included in this study had documented colorectal cancer with peritoneal metastases either on radiological imaging or during previous surgery. All cases were presented in a multidisciplinary meeting where surgical, medical and radiation oncologists, radiologist and pathologists were present, and the decision to proceed with CRS and HIPEC was determined after a consensus was reached. Clinical factors taken into consideration to formulate a decision include patients’ presentation, grade (e.g. presence of signet ring, mucinous or poorly differentiated cells) and stage of tumour, disease free-interval (DFI), response to previous therapies (e.g. chemotherapy or surgery) and radiological images. Patients recommended to undergo CRS and HIPEC were all without distant metastases as determined on imaging. In addition, they were of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) status 0 or 1 [11].

Patients were grouped into two groups: the unresectable group was defined by inoperability determined intra-operatively, which resulted in the abandonment of planned CRS and HIPEC; the resected group was defined by completion of CRS and HIPEC regardless of the completeness of cytoreduction (CC) score, although it was noted that all patients who underwent CRS and HIPEC achieved either CC-0 or CC-1 [12]. The two groups were compared to identify pre-operative factors that will be useful to detect potentially unresectable patients which can help guide pre-operative decision-making and counselling and improve patient selection to decrease the chance of unnecessary exploration.

The clinical pre-operative factors that were analysed included the patients’ presentation, previous response to chemotherapy and/or surgical intervention as well as blood and radiological investigations. Tumour response to chemotherapy was evaluated with the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) criteria [13]. PCI score was calculated intra-operatively during laparotomy. In addition, supplementary data was collected from clinical notes, electronic medical records and surgical records to complete both the PSDSS and PS for the same group of patients.

2.1.Statistical analysis

Between April 2004 and May 2014, 56 patients with pCRC were eligible for CRS and HIPEC. The first 31 patients (discovery set) were used to generate the model and the subsequent 25 patients were used to validate it (validation set). Using the discovery set, univariate analysis identified significant variables (p < 0.1) that were chosen for multivariate analysis. Weights attributed for the significant variables after multivariate analysis (p < 0.05) were obtained from the approximated beta-coefficient value (BC) from multivariate analysis to develop the scoring system (PROPS). Odd ratios (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were also acquired from the multivariate analysis. The scoring systems of PROPS, PSDSS and PS were applied to the validation set to generate a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve to calculate its accuracy, sensitivity and specificity. The Youden’s index was used to identify the optimal cut-off value that gives maximum sensitivity and specificity based on the summary measurement of the ROC curve.

3.Results

Overall, the rate of unresectable cases was 13% (7/56). The demographics between the unresectable and successful groups were comparable except for PCI score and histology (Table 2). All unresectable cases were due to high PCI score with mean score of 24 (SD = 2.6). Of note, the unresectable cases had more tumours with signet ring cell and mucinous histology. Otherwise, the majority of the successful group achieved adequate cytoreduction (93% of CC-0 and CC-1).

Univariate analysis of the discovery set identified ten pre-operative factors significant for unresectability (Table 3). With regards to clinical presentation, patients in the unresectable group were more likely to complain of bloatedness (75% vs. 15%, p = 0.03), and were found to have palpable abdominal masses (25% vs. 0%, p = 0.04) on physical examination. In terms of disease factors, there were a greater proportion of high-grade tumours (50% vs. 4%, p = 0.01) in the unresectable group. For patients who had received treatment prior to the consideration of CRS and HIPEC, more patients from the unresectable group underwent multiple lines of chemotherapy (50% vs. 29%, p = 0.04), displayed progression of disease during chemotherapy (33% vs. 0.0%, p = 0.00) and/or had suboptimal initial resection (25% vs. 7%, p = 0.04). For pre-operative investigations, elevated tumour markers (100% vs. 50%, p = 0.03), as well as CT scan findings of ascites (100% vs. 9%, p = 0.00), omental thickening (100% vs. 4%, p = 0.00) and/or small bowel disease (25% vs. 8%, p = 0.01) were also more common in the unresectable group.

In addition to the above factors, those factors with p < 0.1 were chosen for multivariate analysis. All factors besides progression of disease during chemotherapy were still found to be significant. The remaining nine variables were categorised into three groups to generate PROPS (Table 4). Using the beta-coefficient value, individual scores were assigned to each variable in every group: (i) poor tumour biology (1 point each): suboptimal resection (BC 1.0, OR 0.17, 95% CI 0.05–0.63, p = 0.01), underwent multiple lines of chemotherapy (BC 1.0, OR 0.18, 95% 0.03–0.94, p = 0.07), and high-grade tumour (BC 1.0, OR 0.16, 95% CI 0.04–0.68, p = 0.03); (ii) heavy tumour burden (2 points each): sensation of bloatedness (BC 2.5, OR 0.16, 95% CI 0.04–0.58, p = 0.01), palpable abdominal mass (BC 2.5, OR 0.01, 95% CI 0.00–0.24, p = < 0.01) and computed tomography findings of ascites (BC 2.5, OR 0.02, 95% CI 0.00–0.33, p = < 0.01), small bowel disease (BC 2.5, OR 0.01, 95% CI 0.00–0.17, p = < 0.01) and omental thickening (BC 2.5, OR 0.14, 95% CI 0.02–0.78, p = 0.05); and (iii) active tumour proliferation (2 points): elevated tumour markers (BC 2.5, OR 0.10, 95% CI 0.01–0.84, p = 0.03).

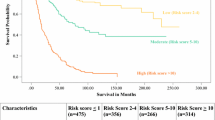

Using the validation set for unresectability prediction (Table 5 and Fig. 1), PROPS achieved 86% accuracy with 100% sensitivity and 68% specificity at a cut-off of 3 (YI 0.68). PSDSS achieved 85% accuracy with 100% sensitivity and 63% specificity at a cut-off of 10 (YI 0.63). PS achieved 73% accuracy with 100% sensitivity and 68% specificity at a cut off of 3 (YI 0.68). And lastly, COMPASS achieved 61% accuracy with 27% sensitivity and 100% specificity at a cut off of 90 (YI 0.27). Of note, at a cut-off of 6, PROPS was able determine unresectability to near absolute certainty (specificity 95%).

4.Discussion

Current pre-operative selection tools such as PSDSS, PS and COMPESS are useful in predicting survival outcomes, but may not be prime in identifying patients with unresectable disease as these studies excluded unresectable cases in their inclusion criteria. Moreover, these studies included intra-operative factors in their model (e.g. PCI in PSDSS and COMPASS and extent of carcinomatosis in PS) that preclude applicability in the pre-operative setting. The one other score available to predict unresectability in pCRC is the mCOREP [14]. We have considered incorporating mCOREP score into the study. However, as this is a retrospective study, we have a significant amount of missing data, in particular the CA125, which rendered the calculation of mCOREP score to be incomplete. The reason why CA125 was not part of our routine pre-operative was because it is specific for ovarian cancer instead of colorectal cancer. In a recent study conducted by Enbald et al., it was found that the mCOREP score (p = 0.9) and PSDSS (p = 0.09) are not predictive of opened and closed laparotomy. Instead, COMPASS score was found to have better predictive value for opened and closed laparotomy as compared to mCOREP score (p < 0.001) [14]. Additionally, Demey et al. have externally validated COMPASS to be superior over PSDSS in its prognostic ability. However, in our paper, we found COMPASS to perform the poorest in predicting unresectability compared to PROPS, PSDSS and PS. This may be attributed to the difference in our patient demographics as the patients in Demey et al. paper were considerably older (57 years old vs. 49 years old) and had lower PCI score (18 vs. 24), which result in discrepancy in the aggregation of COMPASS by approximately 25 points.

Our article demonstrated specific factors for the pre-operative identification of opened and closed cases that we condensed into a novel model—PROPS. At a cut-off of 3, we found that PROPS was best able to detect unresectability (specificity 68%) with the lowest rate of false positive (i.e. complete CRS/HIPEC, sensitivity 100%) compared to PSDSS and PS. At a cut-off of > 6, PROPS can distinguish unresectable cases close to absolute certainty (specificity 95%). The nine factors in PROPS were categorised into three main groups: (i) poor tumour biology, (ii) heavy tumour burden and (iii) active tumour proliferation.

4.1.Poor tumour biology

Advanced cancers have been reported to be one of the main reason for incomplete resection [15]. Extensive disease may preclude complete tumour resection because of technical difficulties or anatomical limitations. As a result, residual disease results in direct tumour extension, metastatic lymph nodes, microvascular invasion or tumour budding [15]. These retained tumours serve as a reservoir and cause larger spillage of tumour emboli, which subsequently result in a greater volume of peritoneal disease [16]. The same rationale holds for a previous suboptimal resection, which may be a harbinger of extensive peritoneal disease that is not remanable with CRS and HIPEC.

In a similar vein, high-grade tumours are also found to be associated with more advanced stage cancers [17,18,19,20,21]. Even in the absence of metastasis, high-grade tumours have a predilection to be locally invasive with increased risks of peritoneal seeding that may result in a hostile abdomen and frozen pelvis [16]. This may be due to their intrinsic properties of cell-cell adhesion disruption that promotes their aggressive behaviour with regard to invasion and metastasis [22]. With greater depth of invasion, it increases the propensity for peritoneal dissemination due to transcoelomic spread in high-grade tumours. Therefore, the degree of peritoneal involvement may be more substantial in high-grade tumours and that could translate to unresectability in CRS and HIPEC.

Acquired resistance to cancer therapies results in progressive disease and thus may require multiple lines of different chemotherapy for disease control. The correlation between progressive disease and multiple lines of chemotherapy may be the reason why the former was no longer found to be significant after multivariate analysis. The need for multiple lines of chemotherapy engenders underlying aggressive cancer [23]. In fact, Cottee et al. has recommended that progressive disease during systemic chemotherapy to be a contraindication to CRS and HIPEC in view of it being a poor prognostic marker to complete cytoreduction [24, 25]. In all, previous suboptimal resection, high-grade tumour and progressive disease whilst on chemotherapy forewarn biological aggressiveness of underlying tumour and may decrease the utility of CRS and HIPEC.

4.2.Heavy tumour burden

Symptomatic colorectal cancers, such as having the sensation of bloatedness, may be an indicator of the extent of the disease. This may also be the presenting symptom in patients who have massive ascites. It confers a poorer prognosis in terms of overall survival and disease-free survival [26, 27]. In addition, palpable abdominal masses may also suggest advanced disease [27]. In general, pCRC patients with clinical symptoms and signs tend to have larger cancers and more advanced local disease [28]. Larger tumours infiltrate the serosal surface over a larger surface area which may increase risk of tumour cells depositing onto the peritoneum via transcoelomic spread [29]. Therefore, having symptoms like bloatedness and detecting abdominal masses during examination are red flags for extensive pCRC that may decrease the chance of a successful CRS and HIPEC. Interestingly, abdominal distension alone was not found to be significant. This implies that the asymptomatic increase in abdominal girth alone is not as specific for unresectability than a symptomatic abdominal distension.

A cause of the aforementioned bloatedness may be due to ascites causing raised abdominal pressure. The formation of ascites is related to altered vascular permeability and obstructed lymphatic system due to the peritoneal disease [30]. This is also in keeping with our finding as high-grade tumours have also been reported to exhibit rapid disease progression that promotes accumulation of intra-peritoneal fluid [30]. As with the presence of clinical symptoms and signs, the formation of ascites is also a grave prognostic sign in pCRC [31, 32]. Studies have shown a positive correlation with the degree of ascites to the extent of tumour burden, that ascites formation occurred in late stages of tumour growth with heavier tumour burden [33]. In fact, there is a positive feedback loop that neoplastic spread in the peritoneal cavity promotes ascites formation which in turn favours deposition, fixation and growth of seeded malignant cells that result in greater volume of ascites [34, 35]. Therefore, CT finding of ascites is an indication of a high-volume peritoneal disease that may result in a higher risk for incomplete CRS and HIPEC.

Omental thickening is commonly seen in patients with pCRC. This is because the omentum is rich in lymphoid tissue and assists in the reabsorption of peritoneal fluid that facilitates neoplastic seeding. It has been shown that the presence of omental thickening connotes advanced disease [36]. On top of that, small bowels may also be inflicted with serosal tumour implants, frank bowel wall invasion and extensive adhesion formations in advanced pCRC as well [37]. This has provided us with evidence that the presence of omental thickening and small bowel disease on CT imaging may suggest underlying heavy tumour peritoneal disease, and thus result in a poorer chance of successful CRS and HIPEC. In addition, our study used CT as an imaging modality to evaluate pCRC pre-operatively. It has been shown that CT may not be sensitive in detecting early pCRC owning to the size of the tumour deposit [38,39,40]. This has resulted in many studies evaluating other modalities such as the MRI or PET scan to detect earlier and smaller pCRC [41,42,43,44,45]. Thus, CT-detected abnormalities may alone represent heavy volume disease due to its inherent inability in detecting early and small peritoneal deposits.

4.3.Active tumour proliferation

The overexpression of tumour markers signify active replicating of tumour cells [46]. Elevated tumour markers are a poor prognostic feature; with higher preoperative level, there will be a higher likelihood of extensive disease [47]. It has been shown that elevated tumour markers contribute to distortion of cellular architecture and facilitates tumour migration [48]. In experimental models, tumours that secrete tumour markers have a greater predilection for metastasis than non-secreting tumours [49]. In keeping with our results, we found that elevated tumour markers in the pre-operative setting were associated with a higher chance of unresectability. Interestingly, several studies have reported that the rise of tumour markers is greatest for liver metastases as compared to locoregional invasion like pCRC [50, 51]. One reason could be that these studies were limited to only carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), while we included additional tumours markers such as CA 19-9. Besides CEA, we found raised CA 19-9 to be a poor prognostic factor. These findings concur with several studies that found association between raised CA 19-9 with pCRC [52,53,54]. Tumour cells that express CA 19-9 were found to be adherent to endothelial cells through E-selectin that promotes tumour metastasis [55, 56]. In particular, tumour cells in the peritoneal cavity bound to CA 19-9 monoclonal antibodies with a high frequency, which may explain the preponderance for peritoneal dissemination for CA 19-9 expressing tumours [57].

This study has a few limitations. Firstly, it is limited by its retrospective nature and single-centre design. The small number in the unresectable group also prohibits sub-group analysis and likely affects the statistical power of the analyses. In studies with small sample size, the chances of type 2 error (false negative) are technically higher without an effect on the rate of type 1 error (false positive). In general, as sample size increases, the chances of type 2 error decrease while the probability of type 1 error increases [58]. Therefore, we believe that even with a large sample size, the variables we found will remain significant. In addition, we are cognizant about the inherent problems of running multivariate analysis in small sample of data due to high standard errors. The challenge of accruing data for opened and closed laparotomy is that it is a hard to reach population. However, multivariate statistical models, specifically ordination (as with most of our variables used in our study), may be statistically powerful enough that the differences among samples are detected even at smaller sample size. That is, small sample size multivariate analysis may produce the same results as studies with large sample size studies. It is recommended that a minimum sample size of 58 individuals will suffice (our study is only off by two counts) [59]. Accordingly, we plan to conduct a larger scale prospective study on a separate group of pCRC patients, to further investigate the utility of PROPS and validate its utility.

5.Conclusion

The PROPS scoring system is a novel pre-operative scoring system that relies solely on pre-operative factors, and is as effective in predicting unresectability compared to the PSDSS, PS and COMPASS.

Moving forward, it will be important to perform external validation for PROPS, and to consider if PROPS can be applied to other tumour types besides colorectal to decrease the incidence of unresectability in planned CRS and HIPEC.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BC:

-

Beta-coefficient value

- CC:

-

Completeness of cytoreduction

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COMPASS:

-

Colorectal Peritoneal Metastases Prognostic Surgical Score

- CRS:

-

Cytoreductive surgery

- DFI:

-

Disease-free interval

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- HIPEC:

-

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy

- OR:

-

Odd ratios

- PCI:

-

Peritoneal carcinomatosis index

- pCRC:

-

Colorectal cancer peritoneal metastases

- PROPS:

-

Pre-Operative Predictive Score

- PS:

-

Verwaal Prognostic Score

- PSDSS:

-

Peritoneal Surface Disease Severity Score

- RECIST:

-

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- YI:

-

Youden’s index

References

Verwaal VJ, et al. Randomized trial of cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy and palliative surgery in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(20):3737–43.

Verwaal VJ, et al. 8-year follow-up of randomized trial: cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(9):2426–32.

Kwakman R, et al. Clinicopathological parameters in patient selection for cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for colorectal cancer metastases: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2016;263(6):1102–11.

Klaver CE, et al. Recommendations and consensus on the treatment of peritoneal metastases of colorectal origin: a systematic review of national and international guidelines. Color Dis. 2017;19(3):224–36.

Simkens GA, et al. Patient selection for cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC for the treatment of peritoneal metastases from colorectal cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2017;9:259–66.

Chang-Yun L, Yonemura Y, Ishibashi H, Sako S, Tsukiyama G, Kitai T, Matsuki N. Evaluation of preoperative computed tomography in estimating peritoneal cancer index in peritoneal carcinomatosis. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2011;38(12):2060–4.

Pelz JO, et al. Evaluation of a peritoneal surface disease severity score in patients with colon cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99(1):9–15.

Verwaal VJ, et al. Predicting the survival of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin treated by aggressive cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Br J Surg. 2004;91(6):739–46.

Simkens GA, van Oudheusden TR, Nieboer D, Steyerberg EW, Rutten HJ, Luyer MD, Nienhuijs SW, de Hingh IH. Development of a prognostic nomogram for patients with peritoneally metastasized colorectal cancer treated with cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(13):4214–21.

Yong ZZ, et al. Unresectability during open surgical exploration in planned cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Int J Hyperth. 2016;32(8):889–94.

Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, ET MF, Carbone PP. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5(6):649–55.

Jacquet P, Sugarbaker PH. Clinical research methodologies in diagnosis and staging of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Cancer Treat Res. 1996;82:359–74.

Eisenhauer EA, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–47.

Enblad M, Ghanipour L, Cashin PH. Prognostic scores for colorectal cancer with peritoneal metastases treated with cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Int J Hyperth. 2018;34(8):1390–5.

Hiranyakas A, da Silva G, Wexner SD, Ho YH, Allende D, Berho M. Factors influencing circumferential resection margin in rectal cancer. Color Dis. 2013;15(3):298–303.

Sugarbaker PH. Patient selection and treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal and appendiceal cancer. World J Surg. 1995;19:235–40.

Gopalan V, et al. Signet-ring cell carcinoma of colorectum—current perspectives and molecular biology. Int J Color Dis. 2011;26(2):127–33.

Hyngstrom JR, et al. Clinicopathology and outcomes for mucinous and signet ring colorectal adenocarcinoma: analysis from the national Cancer data base. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(9):2814–21.

Kim JW, Shin MK, Kim BC. Clinicopathologic impacts of poorly differentiated cluster-based grading system in colorectal carcinoma. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30(1):16–23.

Tawadros PS, Paquette IM, Hanly AM, Mellgren AF, Rothenberger DA, Madoff RD. Adenocarcinoma of the rectum in patients under age 40 is increasing- impact of signet-ring cell histology. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:474–8.

Nitsche U, et al. Prognosis of mucinous and signet-ring cell colorectal cancer in a population-based cohort. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142(11):2357–66.

Sung CO, et al. Clinical significance of signet-ring cells in colorectal mucinous adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(12):1533–41.

Oxnard GR, et al. When progressive disease does not mean treatment failure: reconsidering the criteria for progression. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(20):1534–41.

da Silva RG, Sugarbaker PH. Analysis of prognostic factors in seventy patients having a complete cytoreduction plus perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(6):878–86.

Cotte E, et al. Selection of patients and staging of peritoneal surface malignancies. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2(1):31–5.

Steinberg SM, et al. Prognostic indicators of colon tumors. The gastrointestinal tumor study group experience. Cancer. 1986;57:1866–70.

Cappell MS. Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and management of colon cancer. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2008;37(1):1–24. v

Lee MH, et al. Symptomatic versus asymptomatic colorectal cancer: predictive features at CT colonography. Acad Radiol. 2016;23(6):712–7.

Lemmens VE, et al. Predictors and survival of synchronous peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin: a population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(11):2717–25.

Kelly KJ, Baumgartner JM, Lowy AM. Laparoscopic evacuation of mucinous ascites for palliation of pseudomyxoma peritonei. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(5):1722–5.

Garrison RN, Kaelin LD, Galloway RH, Heuser LS. Malignant ascites. Clinical and experimental observations. Ann Surg. 1986;203(6):644–51.

Shen P, et al. Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy with mitomycin C for peritoneal carcinomatosis from nonappendiceal colorectal carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11(2):178–86.

Nagy JA, Herzberg KT, Dvorak JM, Dvorak HF. Pathogenesis of malignant ascites formation-initiating events that lead to fluid accumulation. Cancer Res. 1993;53:2631–43.

Meyers MA, Charnsangavej C, Oliphant M. Meyers’ dynamic radiology of the abdomen. 6th ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2011.

MA M. Distribution of intra-abdominal malignant seeding- dependency on dynamics of flow of ascitic fluid. Am J Roentgenol Radium Therapy Nucl Med. 1973;119(1):198–206.

Raptopoulos V, Gourtsoyiannis N. Peritoneal carcinomatosis. Eur Radiol. 2001;11(11):2195–206.

Woodward PJ, Hosseinzadeh K, Saenger JS. From the archives of the AFIP- radiologic staging of ovarian carcinoma with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2004;24(1):225–46.

Boudiaf M, Bedda S, Soyer P, Panis Y, Zidi S, Kardache M, Nemeth J, Valleur P, Rymer R. Preoperative evaluation of gastric adenocarcinomas—comparison of CT results with surgical and pathological results. Ann Chir. 1999;53:115–22.

Low RN, Barone RM, Lacey C, Sigeti JS, Alzate GD, Sebrechts CP. Peritoneal tumor-MR imaging with dilute oral barium and intravenous gadolinium-containing contrast agents compared with unenhanced MR imaging and CT. Radiology. 1997;204(5):513–20.

Gryspeerdt S, Clabout L, Van Hoe L, Berteloot P, Vergote IB. Intraperitoneal contrast material combined with CT for detection of peritoneal metastases of ovarian. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1998;19(5):434–7.

Dohan A, et al. Evaluation of the peritoneal carcinomatosis index with CT and MRI. Br J Surg. 2017;104(9):1244–9.

Laghi A, et al. Diagnostic performance of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for detecting peritoneal metastases: systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiol Med. 2017;122(1):1–15.

Turlakow A, Yeung HW, Salmon AS, Macapinlac HA, Larson SM. Peritoneal carcinomatosis—role of 18F-FDG PET. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1407–12.

Liberale G, et al. Accuracy of FDG-PET/CT in colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis: potential tool for evaluation of chemotherapeutic response. Anticancer Res. 2017;37(2):929–34.

Li J, et al. Comparison of PET with PET/CT in detecting peritoneal carcinomatosis: a meta-analysis. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40(7):2660–6.

Goldstein M, Mitchell EP. Carcinoembryonic antigen in the staging and follow-up of patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Investig. 2005;23(4):338–51.

Grem JL, Steinberg SM, Chen AP, McAtee N, Cullen E, Hamilton JM, Allegra CJ. The utility of monitoring carcinoembyronic antigen during systemic therapy for advanced colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 1998;5:559–67.

Benchimol S, Fuks A, Jothy S, Beauchemin N, Shirota K, Stanners CP. Carcinoembryonic antigen, a human tumor marker, functions as an intercellular adhesion molecule. Cell. 1989;57(2):327–34.

Hostetter RB, et al. Carcinoembryonic antigen as a selective enhancer of colorectal cancer metastasis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82(5):380–5.

Kimura O, Kaibara N, Nishidoi H, Okamoto T, Takebayashi M, Kawasumi H, Koga S. Carcinoembryonic antigen slope analysis as an early indicator for recurrence of colorectal carcinoma. Jpn J Surg. 1986;16(2):106–11.

Adams WJ, Morris DL. Carcinoembryonic antigen in the evaluation of therapy of primary and metastatic colorectal cancer. Aust N Z J Surg. 1996;66(8):515–9.

Takakura Y, et al. An elevated preoperative serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 level is a significant predictor for peritoneal dissemination and poor survival in colorectal cancer. Color Dis. 2015;17(5):417–25.

Kaneko M, et al. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 predicts synchronous peritoneal carcinomatosis in patients with colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2017;37(2):865–70.

Kawamura YJ, et al. First alert for recurrence during follow-up after potentially curative resection for colorectal carcinoma: CA 19-9 should be included in surveillance programs. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2010;9(1):48–51.

Berg EL, et al. Comparison of L-selectin and E-selectin ligand specificities: the L-selectin can bind the E-selectin ligands Sialyl Lex and Sialyl Lea. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;184(2):1048–55.

Nakayama T, Watanabe M, Teramoto T, Kitajima M. Slope analysis of CA19-9 and CEA for predicting recurrence in colorectal cancer patients. Anticancer Res. 1997;17(2B):1379–82.

Schott A, Vogel I, Krueger U, Kalthoff H, Schreiber HW, Schmiegel W, Henne-Bruns D, Kremer B, Juhl H. Isolated tumor cells are frequently detectable in the peritoneal cavity of gastric and colorectal cancer patients and serve as a new prognostic marker. Ann Surg. 1998;227(3):372–9.

Banerjee A, et al. Hypothesis testing, type I and type II errors. Ind Psychiatry J. 2009;18(2):127.

Forcino FL, et al. Reexamining sample size requirements for multivariate, abundance-based community research: when resources are limited, the research does not have to be. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0128379.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No financial support was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZYZ participated in data acquisition, data analysis and data interpretation. He was the key contributor in the preparation of the manuscript. GTHC participated in data acquisition, data analysis and data interpretation. She was also involved in editing and reviewing of the manuscript. NS was principally involved in data and statistical analysis. CC was involved in the preparation of the manuscript, along with editing and review its subsequent revisions. MTCC came up with the study concept and study design. She was also involved in the editing and reviewing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the local Centralised Institutional Review Board (SingHealth).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yong, Z.Z., Tan, G.H.C., Shannon, N. et al. P.R.O.P.S. — A novel Pre-Operative Predictive Score for unresectability in patients with colorectal peritoneal metastases being considered for cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). World J Surg Onc 17, 138 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-019-1673-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-019-1673-x