Abstract

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a heterogeneous disease characterized by multiple subtypes and variable disease progression. Blood biomarkers have been variably associated with subtype, severity, and disease progression. Just as combined clinical variables are more highly predictive of outcomes than individual clinical variables, we hypothesized that multiple biomarkers may be more informative than individual biomarkers to predict subtypes, disease severity, disease progression, and mortality.

Methods

Fibrinogen, C-Reactive Protein (CRP), surfactant protein D (SP-D), soluble Receptor for Advanced Glycation Endproducts (sRAGE), and Club Cell Secretory Protein (CC16) were measured in the plasma of 1465 subjects from the COPDGene cohort and 2746 subjects from the ECLIPSE cohort. Regression analysis was performed to determine whether these biomarkers, individually or in combination, were predictive of subtypes, disease severity, disease progression, or mortality, after adjustment for clinical covariates.

Results

In COPDGene, the best combinations of biomarkers were: CC16, sRAGE, fibrinogen, CRP, and SP-D for airflow limitation (p < 10−4), SP-D, CRP, sRAGE and fibrinogen for emphysema (p < 10−3), CC16, fibrinogen, and sRAGE for decline in FEV1 (p < 0.05) and progression of emphysema (p < 10−3), and all five biomarkers together for mortality (p < 0.05). All associations except mortality were validated in ECLIPSE. The combination of SP-D, CRP, and fibrinogen was the best model for mortality in ECLIPSE (p < 0.05), and this combination was also significant in COPDGene.

Conclusion

This comprehensive analysis of two large cohorts revealed that combinations of biomarkers improve predictive value compared with clinical variables and individual biomarkers for relevant cross-sectional and longitudinal COPD outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a global health burden that affects 10% of the world’s population and results in 3 million deaths and $44 billion in health care costs annually. Aside from smoking cessation and oxygen, no available therapies prolong survival or prevent disease progression, with few promising novel drugs in the pipeline [1]. One reason for this is the heterogeneity and complexity of the disease. COPD has multiple subtypes, including emphysema and the frequent exacerbator subtype [2, 3]. In addition, disease progression and mortality are variable and difficult to predict [4, 5]. Although clinical variables such as age, smoking history, dyspnea, exacerbation history, and body mass index (BMI) are somewhat useful to model these subtypes, assess disease severity, and predict disease progression, [6, 7] a large amount of unexplained variance remains.

Since the heterogeneity of COPD extends to the molecular level, there is growing interest in biomarkers to assess disease heterogeneity and predict progression. Biomarkers might identify subgroups of patients who would benefit from specific interventions or may serve as surrogate endpoints, thus enhancing statistical power and reducing the cost of clinical trials. Ultimately, biomarkers may facilitate prognosis and allow us to cater therapies to individual patents (i.e., precision medicine). Moreover, detection of subclinical disease through biomarkers could lead to interventions (e.g., smoking cessation) that could prevent the development of overt COPD. Finally, the identification of biomarkers associated with COPD subtypes or severity may stimulate basic research into the mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of COPD and identify novel therapeutic targets.

Previous studies have identified several blood protein biomarkers of varying value in predicting COPD outcomes (Additional file 1: Table S1) [2]. Fibrinogen and CRP, markers of inflammation, may correlate with disease severity and risk of exacerbations [3, 4, 8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. sRAGE, which dampens inflammation, is inversely correlated with emphysema and airflow limitation [5, 16]. These observations have cemented our understanding that COPD is an inflammatory disease [10]. In fact, both fibrinogen and sRAGE have been considered by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for approval as biomarkers for COPD. Proteins that derive from lung parenchymal cells have also been associated with COPD: SP-D and CC16 with airflow limitation [4, 17, 18] and SP-D with emphysema [5]. However, previous biomarker studies have several limitations. Most have focused on the relationship between biomarkers and cross-sectional outcomes such as subtype and disease severity, information that can be obtained by routine clinical testing. Perhaps the greatest clinical utility of biomarkers lies in their ability to predict disease progression, which is highly variable among COPD patients [4, 5]. The role of biomarkers in predicting longitudinal outcomes has been addressed in a limited number of studies. Fibrinogen and CRP tend to be elevated in patients with frequent exacerbations, but the extent to which biomarkers can predict future exacerbations is unclear [3, 10, 12, 14, 17, 19]. Decline in FEV1 is accelerated but highly variable amongst COPD patients; [4, 20, 21] some evidence suggests that CC16 [4, 22] and sRAGE [23] may be predictive. sRAGE and SP-D have been linked to progression of emphysema [5]. CRP, fibrinogen, CC16, and SP-D have been shown to be associated with mortality, although there are conflicting reports [2, 9,10,11,12, 15, 24, 25]. Another limitation of previous biomarker studies is that most examined a single biomarker. Just as combined clinical variables are more highly predictive of outcomes than individual clinical variables, [6, 26] we hypothesized that multiple biomarkers may be more powerful than individual biomarkers. Some precedent exists for the use of multiple biomarkers in COPD [10, 11, 14] and other diseases [27]. Finally, most COPD biomarker studies examined only one cohort, [5, 10, 11, 14] sometimes a small, single-site cohort, raising the possibility that findings may not be broadly applicable.

As most biomarker studies have been limited to assessing the relationship between individual biomarkers and cross-sectional outcomes and have been performed on a single cohort of patients, we aimed to determine whether a panel of a several biomarkers combined, as measured in two large, independent cohorts, would be more strongly predictive of important disease outcomes, particularly longitudinal outcomes, than individual biomarkers and clinical variables alone. Based on the literature, we evaluated the efficacy of five biomarkers - sRAGE, SP-D, fibrinogen, CC16, and CRP - both individually and in combination, at predicting airflow limitation, severity of emphysema, exacerbations, decline in FEV1, progression of emphysema, and mortality in the COPDGene and ECLIPSE cohorts.

Methods

Study design

Details of the COPDGene and ECLIPSE study protocols, including recruitment, data collection, and longitudinal follow-up are described in the online supplement (Additional File 3) and previous publications [28, 29]. COPDGene (NCT02445183) enrolled 10,300 subjects ages 45–80, of which plasma was collected from 1465 subjects. ECLIPSE (NCT00292552) enrolled 2746 subjects with complete data including biomarkers. Spirometry and high resolution CT scans were performed, and sRAGE, SP-D, high sensitivity (hs) CRP, fibrinogen, and CC16 levels were measured [10, 16,17,18].

Clinical subtypes

COPD was defined by post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio of <0.70. Smoker controls were current or former smokers without evidence of airflow limitation (FEV1/FVC ≥ 0.70). Emphysema was defined by the percent of voxels with Hounsfield Units (HU) < −950 (%LAA) on CT. Severity of emphysema was classified as none (LAA < 5%), mild (LAA 5–10%), moderate (LAA 10–20%), or severe (LAA > 20%) [30, 31]. Air trapping was measured by 3D Slicer. Air trapping was defined by the percent of voxels with HU < −856 on expiratory images. Airway wall thickness at an internal perimeter of 10 mm (pi10) was calculated as described previously [32]. Subjects were classified as having chronic bronchitis if they reported cough productive of sputum present daily for at least 3 months per year, at least 2 years in a row. Longitudinal follow-up (LFU) interviews by telephone or internet were conducted every six months. The number of exacerbations per year was determined. Moderate exacerbations were defined as those treated with steroids and/or antibiotics; severe exacerbations were defined as those resulting in hospitalization. Decline in FEV1 (ml/year) was calculated. Progression of emphysema was calculated as change in %LAA per year. All-cause mortality was determined.

Statistical analysis

Because of non-normality, biomarker values were log transformed. Additional file 1: Table S2 lists statistical models and covariates, which were selected based on previous literature [3,4,5,6,7, 10, 11]. R (v 3.2.0) was used. Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) was used to determine how well a model fit. R2 for clinical covariates (no biomarkers) is reported; the R2 reported for biomarker(s) refers to the R2 of the biomarkers(s) over clinical covariates alone. p-values were determined by two-sided t-tests (or z-tests for the beta, negative binomial and logistic regression, and Cox proportional hazards) for the null hypothesis that β coefficients for biomarker-outcome associations were zero. Biomarker(s) were considered to improve the model if the AIC was lower than clinical covariates alone and p ≤ 0.05. The best combination of biomarkers for a given outcome in the COPDGene cohort was considered to be validated by ECLIPSE if the same combination of biomarkers statistically significantly improved the AIC over clinical covariates alone.

Results

Demographics

Baseline characteristics of the COPDGene and ECLIPSE cohorts are shown in Additional file 1: Tables S3 and S4.

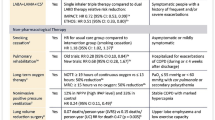

All analyses performed on the COPDGene and ECLIPSE cohorts are shown in Additional file 2: Figure S5 and S6, respectively, with the best model in each cohort highlighted in yellow. The best model in COPDGene is shown in red font on the ECLIPSE analysis (Additional file 1: Table S6).

Airflow limitation (FEV1/FVC and FEV1)

In the COPDGene cohort, CC16, sRAGE, and CRP were each individually associated with FEV1/FVC after adjustment for clinical covariates (Additional file 1: Tables S7 and S5). However, the best model (lowest AIC) in the COPDGene cohort was the combination of CC16, SP-D, CRP, and sRAGE (additional R2 = 0.086 over clinical covariates), and this combination also statistically significantly improved the model in ECLIPSE (Additional file 1: Tables S7 and S6). In both cohorts, every individual biomarker was significantly associated with FEV1, but the combination of all five biomarkers was the most highly associated (Table 1, Fig. 1, Additional file 2: Figure S1, Additional file 1: Tables S5 and S6).

Emphysema

In the COPDGene cohort, SP-D and sRAGE were each individually associated with emphysema after adjusting for clinical covariates (Table 2, Additional file 1: Table S5, Additional file 2: Figure S2). The best model was SP-D, sRAGE, CRP, and fibrinogen combined (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Both the role of SP-D and sRAGE individually and the combination of SP-D, sRAGE, CRP, and fibrinogen were validated in ECLIPSE (Table 2, Additional file 1: Table S6 and Fig. 1).

Exacerbations

In both cohorts, the combination of sRAGE and CRP best modeled total exacerbation frequency over the previous 12 months (Additional file 1: Tables S5, S6 and S8A), whereas SP-D, CRP, sRAGE, and fibrinogen together best modeled previous severe exacerbations (Additional file 1: Tables S5, S6 and S8B, Fig. 1). In the COPDGene cohort, no biomarker(s) was significantly predictive of future total or severe exacerbations after adjustment for prior exacerbations and other clinical covariates (Additional file 1: Tables S5 and S9, Fig. 1).

Decline in FEV1

In COPDGene, fibrinogen predicted decline in FEV1; the best model was CC16, sRAGE, and fibrinogen (Table 3, Additional file 1: Table S5, Fig. 1). In ECLIPSE, these findings were validated but the combination of all five biomarkers was most highly predictive of decline in FEV1 (Table 3, Additional file 1: Table S6, Fig. 1).

Progression of emphysema

After controlling for BMI, female gender, and ongoing cigarette smoking, factors which have previously been identified as risk factors for decline in CT density, [5] the combination of CC16, fibrinogen, and sRAGE was most highly predictive in the COPDGene cohort. This combination was validated in the ECLIPSE cohort, but the combination of all five biomarkers together was more highly predictive (Table 4, Additional file 1: Tables S5 and S6, Fig. 1).

Mortality

BMI, airflow limitation, dyspnea, and exercise capacity (BODE), are moderately predictive of mortality in COPD [6, 7]. To determine whether additional clinical variables improve the model, we performed a stepwise Cox Proportional Hazards analysis with BODE and other variables known to be associated with mortality. The best model in the COPDGene cohort was BODE + age2 + age + gender + exacerbation history, and this was validated in ECLIPSE (Table 5, Additional file 1: Tables S5 and S6).

In the COPDGene cohort, CC16 and SP-D were each individually predictive of mortality, and all five biomarkers was the best model (Table 6, Fig. 1). The combination of all five biomarkers was not validated in ECLIPSE (Table 6, Additional file 1: Table S6); however, the best model in ECLIPSE – the combination of CRP, fibrinogen, and SP-D – was also significant in COPDGene. Of note, when analyzed by C-statistic, none of the biomarkers were associated with mortality in either cohort (Additional file 1: Table S13).

Discussion

COPD is a complex disease, and patients vary greatly and unpredictably in terms of disease subtype, activity, and progression. Pharmacologic agents that prevent disease progression and improve survival are lacking, in part because specific agents are unlikely to benefit such a heterogeneous group of patients [4]. An attractive notion is that biomarkers may provide insight into this heterogeneity, thus allowing us to cater clinical trials and ultimately therapies to specific groups of patients and provide better prognostic information. An extensive literature on biomarkers in COPD exists [1]. However, most studies have examined the association between individual biomarkers and cross-sectional outcomes. In addition, the field has been plagued by lack of validation in replication cohorts and inconsistent biomarker platforms, leading to discrepant reports (Additional file 1: Table S1) [1]. Here, we present a comprehensive analysis of the role of biomarkers, individually and in combination, in predicting both cross-sectional and longitudinal outcomes using two large, multi-center cohorts with identical platforms. We found that individual biomarkers are more closely associated with most outcomes than clinical covariates alone. Moreover, multiple biomarkers are more highly predictive than individual biomarkers for almost all COPD outcomes. With rare exceptions, the associations, including directionality, between biomarkers and outcomes identified in the discovery cohort were validated in the replication cohort (Fig. 1). Additional file 1: Tables S5 and S6 provide an easily accessible and exhaustive resource for investigators to ascertain the association between these biomarkers and almost any clinically important COPD outcome in these two cohorts. To our knowledge, ours is the first study to demonstrate an association between multiple biomarkers and cross-sectional and longitudinal outcomes in two large, multi-center cohorts.

Overall, our findings build upon prior literature, confirming some associations but improving upon existing knowledge by demonstrating that, in most cases, a distinct combination of biomarkers is associated with outcomes. In both cohorts, each of the five biomarkers studied individually correlated with airflow limitation, consistent with previous literature [4, 8, 12, 16,17,18]. However, a panel of five biomarkers together was more highly predictive of airflow limitation (FEV1) than any individual biomarker. Similarly, while previous literature suggested that sRAGE and fibrinogen are individually associated with emphysema, [5, 16] our analysis revealed that the combination of SP-D, CRP, sRAGE, and fibrinogen was more highly correlated.

Although the relationships between biomarkers and disease subtype and severity are interesting and may provide clues into the molecular pathogenesis of the different subtypes, biomarkers will be most useful clinically if they can predict longitudinal outcomes, such as future exacerbations, decline in FEV1, progression of emphysema, and mortality. Such risk stratification would allow clinical trials to be catered to the patients most likely to progress as well as provide patients with a more accurate and personalized prognosis. Interestingly, in the COPDGene cohort, no biomarker or combination of biomarkers added significant value to predicting an individual’s future risk of exacerbations over clinical variables including history of prior exacerbations. This is consistent with previous studies, which found that certain biomarkers were associated with exacerbations by univariate analysis but not by multivariate analysis that included clinical predictive variables, particularly prior exacerbation history [3, 17, 19]. (Although ECLIPSE was used here as a validation cohort, it is interesting to note that biomarkers were predicitve of future exacerbations, and this is likely due to differences in the subjects, such as in race and severity of disease.) One limitation of our study is the lack of blood leukocyte values, which may predict exacerbations [3, 10, 26]. Still, taken together, our findings and the literature suggest that a history of previous exacerbations is so strongly associated with future exacerbations that biomarkers may not provide substantial additional information.

COPD disease progression is highly variable [4, 5]. CC16 levels have been previously associated with decline in FEV1 [4, 22]. Here, the combination of CC16, fibrinogen, and sRAGE best predicted decline in lung function in the COPDGene cohort, and this combination was validated in ECLIPSE, although the addition of SP-D and CRP further improved the model. Whether pro-SP-B, previously implicated in decline in FEV1 [33] would further improve the model should be studied. Progression of emphysema has previously been associated with individual abnormal biomarkers [5]. We found that progression of emphysema, as measured by decline in CT density, was best modeled by the combination of CC16, sRAGE, and fibrinogen in the COPDGene cohort. This model was validated by the ECLIPSE cohort, although the addition of SP-D and CRP further enhanced the model. Whether IL-6, previously associated with progression of emphysema, [5] would further improve the model should be examined.

Although previous studies revealed that multiple biomarkers predict mortality, [9, 11] ours is the first to validate such findings in an independent large, multicenter cohort. However, there were notable discrepancies between the two cohorts. In both cohorts, the combination of SP-D, CRP, and fibrinogen improved the model over covariates and individual biomarkers. However, the best combination in COPDGene, all five biomarkers together, did not reach statistical significance in ECLIPSE. In addition, while fibrinogen or CRP alone were significantly associated with mortality in ECLIPSE (Table 6) and other [9, 13, 15] cohorts, fibrinogen and CRP were not individually predictive of mortality in COPDGene, although they did improve the model when added to the other four biomarkers. These discrepancies may be due to differences between the cohorts, such as in race and severity of disease. The concordance between the two cohorts may become stronger with ongoing follow-up, as the overall mortality rates (9.4% in COPDGene, 8.5% in ECLIPSE) are low, and 3–5 years is a relatively short duration of follow-up considering the natural history of the disease. Future studies should examine mortality over a longer period of follow-up, the contribution of additional biomarkers such as IL-6 and leukocyte count [11] to the model, and disease-specific mortality. Of note, we also report the important finding that inclusion of additional clinical variables known to be associated with mortality (e.g., age) [7] yields a novel clinical model that is more highly predictive of mortality than established models such as the BODE index. In both cohorts, biomarkers strengthen the model, and a combination of biomarkers provides enhanced predictive value over individual biomarkers.

We acknowledge that the amount of variance explained by biomarkers, as determined by correlation coefficients, is relatively low. Longer duration of follow-up and inclusion of additional biomarkers or persistence of abnormal biomarkers [10] may strengthen the correlations. However, our findings are consistent with previously reported weak correlation coefficients (R2 < 0.3) or relative risks (<1.5) [3, 4, 11, 15, 22, 24, 33]. Therefore, the field must acknowledge that statistically significant associations between biomarkers and outcomes that can be observed in large cohorts may be largely inadequate to explain remaining variance after strong clinical covariates are included in the models. This suggests that COPD is an exceedingly heterogeneous and complex disease, the extent of which our understanding remains quite limited. Regardless, the impact of the current study lies in the demonstration that, combinations of biomarkers correlate with COPD outcomes much (two to ten times more) strongly than individual biomarkers.

Limitations of this study, in addition to those discussed above, include the relatively low number of nonsmokers in the COPDGene cohort and the virtual absence of Gold 1 subjects in the ECLIPSE cohort. Neither cohort was population-based. COPDGene results should be generalizable to non-Hispanic white and African American smokers. ECLIPSE results are generalizable to white COPD patients. Although the current findings are overall generalizable because of the size of the discovery and replication cohorts, extensive clinical phenotyping, and adjustment for multiple relevant covariates, these findings should be validated in a third large cohort. Future studies should elucidate the repeatability of biomarker measurements, although most are stable over time [26].

Conclusions

In conclusion, for the first time to our knowledge, we have demonstrated, using two large, multi-center cohorts, that multiple biomarkers are much more strongly predictive than individual biomarkers of almost all important cross-sectional and longitudinal COPD outcomes. The amount of variance explained by biomarkers is lower than clinical variables. Still, we remain optimistic that biomarkers will be useful to limit clinical trials to subgroups of patients likely to benefit from a given intervention and/or serve as surrogate endpoints if they are prospectively demonstrated to correlate with clinically relevant outcomes. As the FDA and EMA have considered approving fibrinogen and RAGE individually as biomarkers for COPD, approval of a panel of multiple biomarkers should be considered.

Abbreviations

- AIC:

-

Akaike information criteria

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CRP:

-

C-Reactive protein

- CC16:

-

Club cell secretory protein

- EMA:

-

European medicines agency

- FDA:

-

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- FEV1 :

-

Forced expiratory volume in the first second

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- HU:

-

Hounsfield units

- SP-D:

-

Surfactant protein D

- sRAGE:

-

Soluble receptor for advanced glycation endproducts

References

Sin DD, Hollander Z, DeMarco ML, McManus BM, Ng RT. Biomarker development for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. from discovery to clinical implementation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:1162–70.

Vestbo J, Agusti A, Wouters EF, Bakke P, Calverley PM, Celli B, Coxson H, Crim C, Edwards LD, Locantore N, et al. Should we view chronic obstructive pulmonary disease differently after ECLIPSE? A clinical perspective from the study team. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:1022–30.

Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, Locantore N, Mullerova H, Tal-Singer R, Miller B, Lomas DA, Agusti A, Macnee W, et al. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1128–38.

Vestbo J, Edwards LD, Scanlon PD, Yates JC, Agusti A, Bakke P, Calverley PM, Celli B, Coxson HO, Crim C, et al. Changes in forced expiratory volume in 1 s over time in COPD. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1184–92.

Coxson HO, Dirksen A, Edwards LD, Yates JC, Agusti A, Bakke P, Calverley PM, Celli B, Crim C, Duvoix A, et al. The presence and progression of emphysema in COPD as determined by CT scanning and biomarker expression: a prospective analysis from the ECLIPSE study. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:129–36.

Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, Casanova C, Montes de Oca M, Mendez RA, Pinto Plata V, Cabral HJ. The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1005–12.

Puhan MA, Garcia-Aymerich J, Frey M, ter Riet G, Anto JM, Agusti AG, Gomez FP, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Moons KG, Kessels AG, Held U. Expansion of the prognostic assessment of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the updated BODE index and the ADO index. Lancet. 2009;374:704–11.

Dahl M, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Vestbo J, Lange P, Nordestgaard BG. Elevated plasma fibrinogen associated with reduced pulmonary function and increased risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1008–11.

Dahl M, Vestbo J, Lange P, Bojesen SE, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. C-reactive protein as a predictor of prognosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:250–5.

Agusti A, Edwards LD, Rennard SI, MacNee W, Tal-Singer R, Miller BE, Vestbo J, Lomas DA, Calverley PM, Wouters E, et al. Persistent systemic inflammation is associated with poor clinical outcomes in COPD: a novel phenotype. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37483.

Celli BR, Locantore N, Yates J, Tal-Singer R, Miller BE, Bakke P, Calverley P, Coxson H, Crim C, Edwards LD, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers improve clinical prediction of mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1065–72.

Duvoix A, Dickens J, Haq I, Mannino D, Miller B, Tal-Singer R, Lomas DA. Blood fibrinogen as a biomarker of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2013;68:670–6.

Mannino DM, Valvi D, Mullerova H, Tal-Singer R. Fibrinogen, COPD and mortality in a nationally representative U.S. cohort. COPD. 2012;9:359–66.

Thomsen M, Ingebrigtsen TS, Marott JL, Dahl M, Lange P, Vestbo J, Nordestgaard BG. Inflammatory biomarkers and exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2013;309:2353–61.

Mannino DM, Tal-Singer R, Lomas DA, Vestbo J, Graham Barr R, Tetzlaff K, Lowings M, Rennard SI, Snyder J, Goldman M, et al. Plasma fibrinogen as a biomarker for mortality and hospitalized exacerbations in people with COPD. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis (Miami). 2015;2:23–34.

Cheng DT, Kim DK, Cockayne DA, Belousov A, Bitter H, Cho MH, Duvoix A, Edwards LD, Lomas DA, Miller BE, et al. Systemic soluble receptor for advanced glycation endproducts is a biomarker of emphysema and associated with AGER genetic variants in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:948–57.

Lomas DA, Silverman EK, Edwards LD, Locantore NW, Miller BE, Horstman DH, Tal-Singer R, Evaluation of CLtIPSEsi. Serum surfactant protein D is steroid sensitive and associated with exacerbations of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:95–102.

Lomas DA, Silverman EK, Edwards LD, Miller BE, Coxson HO, Tal-Singer R. Evaluation of serum CC-16 as a biomarker for COPD in the ECLIPSE cohort. Thorax. 2008;63:1058–63.

Keene JD, Jacobson S, Kechris K, Kinney GL, Foreman MG, Doerschuk CM, Make BJ, Curtis JL, Rennard SI, Barr RG, et al.: Biomarkers Predictive of Exacerbations in the SPIROMICS and COPDGene Cohorts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;15;195(4):473-81.

Casanova C, de Torres JP, Aguirre-Jaime A, Pinto-Plata V, Marin JM, Cordoba E, Baz R, Cote C, Celli BR. The progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is heterogeneous: the experience of the BODE cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1015–21.

Nishimura M, Makita H, Nagai K, Konno S, Nasuhara Y, Hasegawa M, Shimizu K, Betsuyaku T, Ito YM, Fuke S, et al. Annual change in pulmonary function and clinical phenotype in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:44–52.

Park HY, Churg A, Wright JL, Li Y, Tam S, Man SF, Tashkin D, Wise RA, Connett JE, Sin DD. Club cell protein 16 and disease progression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:1413–9.

Iwamoto H, Gao J, Pulkkinen V, Toljamo T, Nieminen P, Mazur W. Soluble receptor for advanced glycation end-products and progression of airway disease. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;14:68.

Man SF, Connett JE, Anthonisen NR, Wise RA, Tashkin DP, Sin DD. C-reactive protein and mortality in mild to moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2006;61:849–53.

Fibrinogen Studies C, Danesh J, Lewington S, Thompson SG, Lowe GD, Collins R, Kostis JB, Wilson AC, Folsom AR, Wu K, et al. Plasma fibrinogen level and the risk of major cardiovascular diseases and nonvascular mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis. JAMA. 2005;294:1799–809.

Thomsen M, Dahl M, Lange P, Vestbo J, Nordestgaard BG. Inflammatory biomarkers and comorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:982–8.

Ganz P, Heidecker B, Hveem K, Jonasson C, Kato S, Segal MR, Sterling DG, Williams SA. Development and validation of a protein-based risk score for cardiovascular outcomes among patients with stable coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2016;315:2532–41.

Regan EA, Hokanson JE, Murphy JR, Make B, Lynch DA, Beaty TH, Curran-Everett D, Silverman EK, Crapo JD. Genetic epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) study design. COPD. 2010;7:32–43.

Vestbo J, Anderson W, Coxson HO, Crim C, Dawber F, Edwards L, Hagan G, Knobil K, Lomas DA, MacNee W, et al. Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate End-points (ECLIPSE). Eur Respir J. 2008;31:869–73.

Carolan BJ, Hughes G, Morrow J, Hersh CP, O’Neal WK, Rennard S, Pillai SG, Belloni P, Cockayne DA, Comellas AP, et al. The association of plasma biomarkers with computed tomography-assessed emphysema phenotypes. Respir Res. 2014;15:127.

Schroeder JD, McKenzie AS, Zach JA, Wilson CG, Curran-Everett D, Stinson DS, Newell Jr JD, Lynch DA. Relationships between airflow obstruction and quantitative CT measurements of emphysema, air trapping, and airways in subjects with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201:W460–70.

Nakano Y, Wong JC, de Jong PA, Buzatu L, Nagao T, Coxson HO, Elliott WM, Hogg JC, Pare PD. The prediction of small airway dimensions using computed tomography. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:142–6.

Leung JM, Mayo J, Tan W, Tammemagi CM, Liu G, Peacock S, Shepherd FA, Goffin J, Goss G, Nicholas G, et al. Plasma pro-surfactant protein B and lung function decline in smokers. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:1037–45.

Acknowledgements

COPDGene Cores:

Administrative Core: James Crapo, MD (PI), Edwin Silverman, MD, PhD (PI), Barry Make, MD, Elizabeth Regan, MD, PhD, Rochelle Lantz, Lori Stepp, Sandra Melanson

Genetic Analysis Core: Terri Beaty, PhD, Barbara Klanderman, PhD, Nan Laird, PhD, Christoph Lange, PhD, Michael Cho, MD, Stephanie Santorico, PhD, John Hokanson, MPH, PhD, Dawn DeMeo, MD, MPH, Nadia Hansel, MD, MPH, Craig Hersh, MD, MPH, Peter Castaldi, MD, MSc, Merry-Lynn McDonald, PhD, Jin Zhou, MD, PhD, Manuel Mattheissen, MD, PhD, Emily Wan, MD, Megan Hardin, MD, Jacqueline Hetmanski, MS, Margaret Parker, MS, Tanda Murray, MS

Imaging Core: David Lynch, MB, Joyce Schroeder, MD, John Newell, Jr., MD, John Reilly, MD, Harvey Coxson, PhD, Philip Judy, PhD, Eric Hoffman, PhD, George Washko, MD, Raul San Jose Estepar, PhD, James Ross, MSc, Mustafa Al Qaisi, MD, Jordan Zach, Alex Kluiber, Jered Sieren, Tanya Mann, Deanna Richert, Alexander McKenzie, Jaleh Akhavan, Douglas Stinson

PFT QA Core, LDS Hospital, Salt Lake City, UT: Robert Jensen, PhD

Biological Repository, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD: Homayoon Farzadegan, PhD, Stacey Meyerer, Shivam Chandan, Samantha Bragan

Data Coordinating Center and Biostatistics, National Jewish Health, Denver, CO: Douglas Everett, PhD, Andre Williams, PhD, Carla Wilson, MS, Anna Forssen, MS, Amber Powell, Joe Piccoli

Epidemiology Core, University of Colorado School of Public Health, Denver, CO: John Hokanson, MPH, PhD, Marci Sontag, PhD, Jennifer Black-Shinn, MPH, Gregory Kinney, MPH, PhDc, Sharon Lutz, MPH, PhD.

COPDGene Investigators:

Ann Arbor VA: Jeffrey Curtis, MD, Ella Kazerooni, MD

Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX: Nicola Hanania, MD, MS, Philip Alapat, MD, Venkata Bandi, MD, Kalpalatha Guntupalli, MD, Elizabeth Guy, MD, Antara Mallampalli, MD, Charles Trinh, MD, Mustafa Atik, MD, Hasan Al-Azzawi, MD, Marc Willis, DO, Susan Pinero, MD, Linda Fahr, MD, Arun Nachiappan, MD, Collin Bray, MD, L. Alexander Frigini, MD, Carlos Farinas, MD, David Katz, MD, Jose Freytes, MD, Anne Marie Marciel, MD

Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA: Dawn DeMeo, MD, MPH, Craig Hersh, MD, MPH, George Washko, MD, Francine Jacobson, MD, MPH, Hiroto Hatabu, MD, PhD, Peter Clarke, MD, Ritu Gill, MD, Andetta Hunsaker, MD, Beatrice Trotman-Dickenson, MBBS, Rachna Madan, MD

Columbia University, New York, NY: R. Graham Barr, MD, DrPH, Byron Thomashow, MD, John Austin, MD, Belinda D’Souza, MD

Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC: Neil MacIntyre, Jr., MD, Lacey Washington, MD, H Page McAdams, MD

Fallon Clinic, Worcester, MA: Richard Rosiello, MD, Timothy Bresnahan, MD, Joseph Bradley, MD, Sharon Kuong, MD, Steven Meller, MD, Suzanne Roland, MD

Health Partners Research Foundation, Minneapolis, MN: Charlene McEvoy, MD, MPH, Joseph Tashjian, MD

Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD: Robert Wise, MD, Nadia Hansel, MD, MPH, Robert Brown, MD, Gregory Diette, MD, Karen Horton, MD

Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA: Richard Casaburi, MD, Janos Porszasz, MD, PhD, Hans Fischer, MD, PhD, Matt Budoff, MD, Mehdi Rambod, MD

Michael E. DeBakey VAMC, Houston, TX: Amir Sharafkhaneh, MD, Charles Trinh, MD, Hirani Kamal, MD, Roham Darvishi, MD, Marc Willis, DO, Susan Pinero, MD, Linda Fahr, MD, Arun Nachiappan, MD, Collin Bray, MD, L. Alexander Frigini, MD, Carlos Farinas, MD, David Katz, MD, Jose Freytes, MD, Anne Marie Marciel, MD

Minneapolis VA: Dennis Niewoehner, MD, Quentin Anderson, MD, Kathryn Rice, MD, Audrey Caine, MD

Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA: Marilyn Foreman, MD, MS, Gloria Westney, MD, MS, Eugene Berkowitz, MD, PhD

National Jewish Health, Denver, CO: Russell Bowler, MD, PhD, David Lynch, MB, Joyce Schroeder, MD, Valerie Hale, MD, John Armstrong, II, MD, Debra Dyer, MD, Jonathan Chung, MD, Christian Cox, MD

Temple University, Philadelphia, PA: Gerard Criner, MD, Victor Kim, MD, Nathaniel Marchetti, DO, Aditi Satti, MD, A. James Mamary, MD, Robert Steiner, MD, Chandra Dass, MD, Libby Cone, MD

University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL: William Bailey, MD, Mark Dransfield, MD, Michael Wells, MD, Surya Bhatt, MD, Hrudaya Nath, MD, Satinder Singh, MD

University of California, San Diego, CA: Joe Ramsdell, MD, Paul Friedman, MD

University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA: Alejandro Cornellas, MD, John Newell, Jr., MD, Edwin JR van Beek, MD, PhD

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI: Fernando Martinez, MD, MeiLan Han, MD, Ella Kazerooni, MD

University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN: Christine Wendt, MD, Tadashi Allen, MD

University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA: Frank Sciurba, MD, Joel Weissfeld, MD, MPH, Carl Fuhrman, MD, Jessica Bon, MD, Danielle Hooper, MD

University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX: Antonio Anzueto, MD, Sandra Adams, MD, Carlos Orozco, MD, Mario Ruiz, MD, Amy Mumbower, MD, Ariel Kruger, MD, Carlos Restrepo, MD, Michael Lane, MD

ECLIPSE Investigators [11].

Funding

Grant Support: National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI RO1 HL095432, U01 HL089856, U01 HL089897, P20 HL113445, HHSN26820090020CP30); National Center for Research Resources (NCRR UL1 RR025780); Flight Attendant Medical Research Foundation; GSK funded the biomarker assays.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

RLZ., KK, and RPB designed the study; RLZ, SJ, KK, and R.P.B. analyzed data; RLZ., JK, KK, and RPB, interpreted data and wrote the manuscript. BEM and RT were involved in study design and data generation and reviewed the manuscript. RLZ, SJ, and RPB. had full access to all the data in the study, interpreted the data and prepared the manuscript independently, and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

R.L.Z., S.J., K.K., and J.K. have no financial or personal relationships with people or organizations that could inappropriately influence this work. B.E.M. and R.T. are employees and shareholders of GSK. R.P.B. is on the advisory boards of GSK, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Astra-Zeneca and has research grants from Boehringer-Ingelheim and MedImmune.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Subjects provided informed consent, and institutional review boards of participating sites approved the study (Additional file 1: Table S10 and [11]).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Association Between Biomarkers and COPD Outcomes. Table S2. Statistical Models. Table S3. Demographics of Subjects at Baseline: COPDGene Cohort*. Table S4. Demographics of Subjects at Baseline: ECLIPSE Cohort*. Table S5. Analysis of COPDGene cohort. Grey shading indicates each model with lines for each biomarker in that model. Columns are beta coefficient in model (B), odds ratio, standard error (SE), correlation coefficient (R2) or pseudo R2 Cragg and Uhler’s (CU) or R2m (the marginal portion of the R2), Akaike Information Criteria (AIC), and number of subjects analyzed (N). The type of model is listed on top right of table. The best model highlighted in yellow. Table S6. Analysis of ECLIPSE cohort. Best model in ECLIPSE cohort highlighted in yellow. Grey shading indicates each model with lines for each biomarker in that model. Columns are beta coefficient in model (B), odds ratio, standard error (SE), correlation coefficient (R2) or pseudo R2 Cragg and Uhler’s (CU) or R2m (the marginal portion of the R2), Akaike Information Criteria (AIC), and number of subjects analyzed (N). The type of model is listed on top right of table. Best model in COPDGene cohort in red font. Table S7. Biomarkers Associated with FEV1/FVC. Table S8. Biomarkers Associated with (A) Total (Moderate and Severe) Exacerbations and (B) Severe Exacerbations in the Previous 12 Months. Table S9. Biomarkers Associated with (A) Prospective Total (Moderate and Severe) Exacerbations or (B) Prospective Severe Exacerbations. Table S10. Enrollment Centers. Table S11. Baseline Characteristics of Subjects with Biomarker Data Compared with Entire COPDGene Cohort. Table S12. Correlation Between Biomarkers. Table S13. Biomarkers Associated with Mortality. Analysis of COPDGene and ECLIPSE cohorts by C-statistic. Covariates were BODE, age, age2, gender, and severe exacerbations. (ZIP 485 kb)

Additional file 2: Figure S1.

Distribution of Biomarkers. Biomarker levels were log transformed. Figure S2. Relationship Between Individual Biomarkers and FEV1. Beeswarm/box plot of biomarker levels in never smokers, smokers with normal lung function PRISm, and Gold Stage 1–4 COPD patients. Central box bars represent the median and end box bars represent the first and third quartiles. Analysis by linear regression. *p < 10−5. Figure S3. Relationship Between Individual Biomarkers and Emphysema. Analysis performed by ordinal logistic regression. Covariates were FEV1, age, smoking status, gender, race, and BMI. % Emphysema defined as % of voxels with HU < −950. *p < 0.01. (PDF 312 kb)

Additional file 3:

Supplemental Methods. (DOCX 76 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zemans, R.L., Jacobson, S., Keene, J. et al. Multiple biomarkers predict disease severity, progression and mortality in COPD. Respir Res 18, 117 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-017-0597-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-017-0597-7