Abstract

Background

Escherichia coli are mostly commensals but also contain pathogenic lineages. It is largely unclear whether the commensal E. coli as the potential origins of pathogenic lineages may consist of monophyletic or polyphyletic populations, elucidation of which is expected to lead to novel insights into the associations of E. coli diversity with human health and diseases.

Methods

Using genomic sequencing and pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) techniques, we analyzed E. coli from the intestinal microbiota of three groups of healthy individuals, including preschool children, university students, and seniors of a longevity village, as well as colorectal cancer (CRC) patients, to probe the commensal E. coli populations for their diversity.

Results

We delineated the 2280 fresh E. coli isolates from 185 subjects into distinct genome types (genotypes) by PFGE. The genomic diversity of the sampled E. coli populations was so high that a given subject may have multiple genotypes of E. coli, with the general diversity within a host going up from preschool children through university students to seniors. Compared to the healthy subjects, the CRC patients had the lowest diversity level among their E. coli isolates. Notably, E. coli isolates from CRC patients could suppress the growth of E. coli bacteria isolated from healthy controls under nutrient-limited culture conditions.

Conclusions

The coexistence of multiple E. coli lineages in a host may help create and maintain a microbial environment that is beneficial to the host. As such, the low diversity of E. coli bacteria may be associated with unhealthy microenvironment in the intestine and hence facilitate the pathogenesis of diseases such as CRC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Escherichia coli had been generally known as commensal bacterial components of the normal microbiota in the gastrointestinal tract of humans and animals until the 1940s, when a variety of pathogenic strains began to be reported [1]. Pathogenic E. coli have different types, causing intestinal (see a nice review in [2]) or extra-intestinal infections [3,4,5,6]. New pathogenic types of E. coli, such as E. coli strains associated with Crohn disease [7,8,9] as well as those associated with colorectal cancer (CRC) [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17], have continually been reported. Bacteria in the Shigella genus are closely related to E. coli and have been treated as pathogenic branches of E. coli [18, 19]; E. coli and Shigella together are often referred to as E. coli complex bacteria. To date, a large number of pathogenic E. coli isolates have been extensively studied and categorized into phylogenetic groups or clonal complexes according to their genetic differences due largely to their clinical significance [20,21,22,23]. However, whether the commensals, as potential evolutionary origins of the emerged and emerging pathogens, consist of monophyletic or polyphyletic E. coli populations is unclear.

In this study, we collected 2280 E. coli isolates from fresh fecal specimens of healthy individuals in three age groups, who did not have intestinal or extra-intestinal illnesses, and of CRC patients for comparative studies. Based on their genomic differences, we delineated the bacteria into discrete genomic types (genotypes). In general, the analyzed E. coli isolates were highly diverse, with one genotype having from several hundred to over a thousand genes not found in any other types compared and a particular participant harboring from a single to multiple genotypes of E. coli. Remarkably, the diversity went up with age in the groups of healthy subjects, from preschool children through university students to seniors of a longevity village, but the CRC patients of all ages had the lowest diversity. These results suggest that the coexistence of multiple benign E. coli lineages in the same microbiota may help create a beneficial microbial environment for human health.

Methods

Bacterial strains

Fecal specimens were collected from 68 preschool children of Yifu Kindergarten, three to six years old; 87 university students of Harbin Medical University, 17 to 22 years old; 15 senior people of Bama Longevity Village, Guangxi Province, 90 to 106 years old; and 15 colorectal cancer (CRC) patients from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, 34 to 77 years old (Table 1). The healthy participants did not have intestinal or extra-intestinal illnesses, and the CRC patients were diagnosed by experts of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University. The participants of all four groups did not use any antimicrobials in the past 6 months prior to specimen collection. We obtained a written informed consent from each participant or their guardian and the present work was approved by the Ethics Committee of Harbin Medical University. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, consistent with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. For isolating the bacteria, we spread 30 μl X-gal (20 mg/ml) on the LB plate [24] and purified the bacteria by streaking a single blue colony on fresh LB plates. Bacterial identification was performed at the Clinical Laboratory of the Second Affiliated Hospital, Harbin Medical University, and all bacterial strains were confirmed to be E. coli before analyses. The bacterial strains were stocked at -80 °C in 25% glycerol and streaked on an LB plate for another round of single colony isolation by incubation at 37 °C overnight prior to use.

Genomic comparisons by pulsed field gel electrophoresis techniques

Methods for intact genomic DNA extraction from the bacteria and PFGE analyses were according to the protocols published previously [25,26,27]. The endonuclease I-CeuI recognizes phylogenetic diversity of the bacteria from the genus and up levels [27,28,29] and cleavage data from the CTAG-recognizing endonucleases reflect bacterial diversity at the species level, which are consistent with genomic sequence data [30,31,32,33].

Genomic sequencing and analysis

Genomic sequencing of the bacteria was conducted on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform, which produced 620 Mb data for each of the strains. Library construction and sequencing were carried out according to the manufacturer’s recommendation at the Illumina web site. The sequence data from Illumina HiSeq 2000 were assembled with SOAPdenovo 2.04 software and the sequence analysis was performed as previously described [34, 35]. The draft genome sequences can be accessed under accession numbers shown in Table 2. We predicted genes from the assembled sequences using Glimmer 3.02 [66, 67].

Phylogenetic analysis

Orthologs were determined by BLAST alignment with the criteria that identity was larger than 70% and alignment length was longer than 70% of the whole gene. Concatenation of conserved genes was done by using home-made Perl scripts. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by MEGA6.

Detection of genetic boundaries

The detection of genetic boundaries was performed as previously described [68].

Probing the pan-genomes

We determined the genes common to all compared strains and used the genes as the “core-genome” for the strains compared; we added all non-redundant genes of the bacterial strains in comparison to the core-genome to obtain the “pan-genome”. The analysis of pan-genomes and core-genomes was done by using home-made Perl scripts.

Growth competition assays among the E. coli strains in different nutrient conditions

For the growth competition assays, we mixed three strains in a set, including one from a CRC patient and two from two separate healthy subjects. We inoculated a single colony from a strain into 4 ml LB broth and incubated the bacteria at 37 °C overnight. On day 1 of the growth competition assays, we transferred 1 ml of each of the three overnight cultures in a set into one fresh 15 ml test tube with a water-tight cap (for genomic DNA extraction manipulations [25];). After brief vortex mixing, we transferred an aliquot of 30 μl into a 10 ml test tube containing 3 ml LB broth and another aliquot of 30 μl into a 10 ml test tube containing 3 ml M9 medium [69] and incubated the 100-fold diluted cultures overnight at 37 °C with shaking (200 rpm); all ensuing cultures were conducted under such conditions. Then we extracted genomic DNA of the bacteria from each of the three single overnight cultures and the pooled cultures 1 ml each from the three single overnight cultures by procedures provided previously [25].

On day 2 of the assays, the overnight cultures initiated on day 1 were 100-fold diluted again (a 30 μl aliquot into a 10 ml test tube containing 3 ml LB broth and a another aliquot of 30 μl into a 10 ml test tube containing 3 ml M9 medium). This procedure was repeated daily until day 10, when a 30 μl aliquot from the day 10 LB culture was transferred into a 10 ml test tube containing 3 ml LB broth as usual and the 30 μl aliquot from the day 10 M9 culture was transferred into a 10 ml test tube also containing 3 ml LB broth, not M9 medium, to obtain sufficient bacterial cells for genomic DNA extraction on day 11.

The procedure of dilution and culture was terminated on day 11 and genomic DNA was extracted from the bacteria of the end cultures.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted by using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and GraphPad Prism statistical software; as the data were not normally distributed, Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used.

Results

Genomic diversity of E. coli in healthy people and CRC patients

To probe the general diversity of commensal E. coli in the human microbiota and test for any possible associations between the diversity and health status, we made genomic comparisons on the 2280 E. coli isolates (see details in Methods and Table 1). To reveal the overall genomic differences among the E. coli strains, we profiled the endonuclease cleavage patterns of the bacteria using the pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) techniques, which reflect relatedness of the bacteria and can delineate very closely related bacteria into distinct phylogenetic lineages [28, 31]. We found that the E. coli strains had highly diverse cleavage patterns; particularly, the endonuclease I-CeuI delineated the E. coli strains into distinct genotypes (Fig. 1). I-CeuI cleaves a 26 bp sequence in the 23S rRNA genes [70, 71], which are evolutionarily conserved in both genomic location and nucleotide sequence, so its cleavage patterns reflect genomic distribution of the 23S rRNA genes and hence the overall physical structure of the bacterial genome [27, 28].

PFGE patterns of E. coli strains from four participant groups. a Preschool children (3–6 years old). Lanes: 1, Concatenated λ DNA as molecular size marker; 2, ccpm4786; 3, ccpm4787; 4, ccpm4788; 5, ccpm4789; 6, ccpm4790; 7, ccpm4791; 8, ccpm4792; 9, ccpm4793; 10, ccpm4794; 11, ccpm4795; 12, ccpm4796; 13, ccpm4797; 14, ccpm4798; 15, ccpm4799; 16, ccpm4800; 17, ccpm4801; 18, ccpm4802; 19, ccpm4803; 20, ccpm4804; 21, ccpm4805; 22, ccpm4806; 23, ccpm4807; 24, ccpm4808; 25, ccpm4809; 26, ccpm4834; 27, ccpm4835; 28, ccpm4836; 29, ccpm4837; 30, ccpm4838; 31, ccpm4839; 32, ccpm4840; 33, ccpm4841; 34, ccpm4842; 35, ccpm4843; 36, ccpm4844; 37, ccpm4845. b University students (17–22 years old). Lanes: 1, Concatenated λ DNA as molecular size marker; 2, ccpm5554; 3, ccpm5555; 4, ccpm5556; 5, ccpm5557; 6, ccpm5558; 7, ccpm5559; 8, ccpm5560; 9, ccpm5561; 10, ccpm5562; 11, ccpm5563; 12, ccpm5564; 13, ccpm5565; 14, ccpm5566; 15, ccpm5567; 16, ccpm5568; 17, ccpm5569; 18, ccpm5570; 19, ccpm5571; 20, ccpm5572; 21, ccpm5573; 22, ccpm5574; 23, ccpm5575; 24, ccpm5576; 25, ccpm5577; 26, ccpm5578; 27, ccpm5579; 28, ccpm5580; 29, ccpm5581; 30, ccpm5582; 31, ccpm5583; 32, ccpm5584; 33, ccpm5585; 34, ccpm5586; 35, ccpm5587; 36, ccpm5588; 37, ccpm5589. c Senior individuals (90–106 year old). Lanes: 1, Concatenated λ DNA as molecular size maker; 2, 9-MK1; 3, 9-MK2; 4, 9-MK3; 5, 9-MK4; 6, 9-MK5; 7, 9-MK6; 8, 9-MK7; 9, 9-MK8; 10, 9-CB1; 11, 9-CB2; 12, 9-CB3; 13, 9-CB4; 14, 9-CB5; 15, 9-CB6; 16, 9-CB7; 17, 9-CB8; 18, 11-MK1; 19, 11-MK2; 20, 11-MK3; 21, 11-MK4; 22, 11-MK5; 23, 11-MK6; 24, 11-MK7; 25, 11-MK8; 26, 11-CB1; 27, 11-CB2; 28, 11-CB3; 29, 11-CB4; 30, 11-CB5; 31, 11-CB6; 32, 11-CB7; 33, 11-CB8; 34, 15-MK1; 35, 15-MK2; 36, 15-MK3; 37, 15-MK4; 38, 15-MK5; 39, 15-MK6. d CRC cancer patients (34–77 years old). Lanes: 1, Concatenated λ DNA as molecular size maker; 2, ccpm6546; 3, ccpm6547; 4, ccpm6548; 5, ccpm6549; 6, ccpm6550; 7, ccpm6551; 8, ccpm6552; 9, ccpm6553; 10, ccpm6554; 11, ccpm6555; 12, ccpm6556; 13, ccpm6557; 14, ccpm6558; 15, ccpm6559; 16, ccpm6560; 17, ccpm6561; 18, ccpm6562; 19, ccpm6563; 20, ccpm6564; 21, ccpm6565; 22, ccpm6566; 23, ccpm6567; 24, ccpm6568; 25, ccpm6569; 26, ccpm6570; 27, ccpm6571; 28, ccpm6572; 29, ccpm6573; 30, ccpm6574; 31, ccpm6575; 32, ccpm6576; 33, ccpm6577; 34, ccpm6578; 35, ccpm6579; 36, ccpm6580; 37, ccpm6581

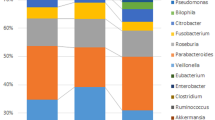

Although in general the E. coli isolates from the 185 participants had high genomic diversity, the level of diversity was different considerably among the groups: from very low to remarkably high among the individual participants (see Table 1). Notably, the magnitude of diversity went up with age in the healthy participants from preschool children through university students to senior individuals, whereas the colorectal cancer patients all had low diversity and the differences were statistically significant (Fig. 2). As shown in Table 1, as many as 13 genome types were resolved from the 16 randomly picked E. coli isolates of a senior individual, which suggests that higher diversity might be detected if more isolates from a subject were examined. To look into this, we extended the number of isolates from 12 to 16 per person to 60 in a subset of the subjects for the analysis; however, no further diversity was detected (data not shown).

Diversity of E. coli in different age and health status groups. a Levels of E. coli diversity in the individual groups. The diversity is illustrated by percentages of participants in a group that have one, two or more genomic types among the E. coli strains analyzed. b Statistical comparisons of E. coli diversity among the four groups. ***: p < 0.0001 (Children vs Students, p-value = 3.291e-09; Children vs Seniors, p-value = 3.104e-10; Students vs Seniors, p-value = 7.226e-06; Seniors vs CRC patients, p-value = 6.83e-06; Students vs CRC patients, p-value = 0.0039; Children vs CRC patients, p-value = 0.8847.). Note that most CRC patients had only one genotype and most senior individuals had five or more genotypes

Phylogenetic divergence of the E. coli strains

The high diversity of the analyzed E. coli strains as reflected by their I-CeuI profiles suggests different gene contents among the E. coli bacteria. To look into this, we sequenced 25 selected strains to make genomic comparisons at higher resolution and determine the phylogenetic relationships among them. We constructed a phylogenetic tree for the 25 E. coli strains along with 37 reference E. coli complex strains, representing phylogenetic groups A, B1, B2, D, E and Shigella lineages, as well as 12 reference Salmonella strains, representing the leading pathogens (Table 2), by concatenating and comparing 927 genes common to them. We included these reference E. coli and Salmonella strains in the phylogenetic analysis to estimate the evolutionary relationships as well as the genetic distances among the E. coli strains. On the constructed tree, the 25 E. coli strains were either mixed with strains of a phylogenetic group of E. coli (ccpm6201, ccpm5179, ccpm5064, ccpm5071, ccpm5063, ccpm5065, ccpm6207, ccpm6219, ccpm5177, ccpm5176, ccpm5174, ccpm6220, ccpm5175, BAMA0321 and BAMA0315 with Group A; ccpm5062, BAMA0361 and BAMA0374 with Group B1; and ccpm5069, ccpm6195 and BAMA0397 with Group D) or formed a branch between the groups (ccpm5172, ccpm3961 and ccpm3962 between Groups B1 and E). Additionally, ccpm5171 was clustered together with Shigella; none of the 25 strains was found to cluster with Group B2, which contains many extra-intestinal pathogens [72,73,74], or E, which contains O157:7 and O55:H7 [56] (Fig. 3). Also as shown in Fig. 3, the six strains of subject ZGQ and the seven strains of subject TZL (see Table 1 for details about subjects ZGQ and TZL) were broadly distributed on the phylogenetic tree without a clear tendency of clustering toward their origin hosts. On the other hand, some E. coli strains isolated from different hosts were closely related, such as ccmp3961 and ccpm3962 from WZW with ccpm5172 from TZL, and ccpm5065 from ZGQ with ccpm6207 from CRC-EC2, demonstrating the spreading of E. coli strains among the human populations (Fig. 3). Notably, genetic distances among the E. coli strains (including reference E. coli complex strains and the 25 E. coli strains isolated in this study) were similar to, or even greater than, those seen among the Salmonella lineages, indicating their phylogenetic divergence over evolutionary times.

Phylogenetic tree for comparisons of relative genetic distances among the bacteria. On the left is a phylogenetic tree for strains of both E. coli and Salmonella and on the right is an enlarged part of the phylogenetic tree for E. coli. The tree was constructed with 1000 bootstrap replicates by the neighbor-joining (NJ) method

Genetic boundaries among the E. coli lineages

Such a high genetic diversity of the commensal E. coli isolates and the remarkable evolutionary distances among them suggest the existence of genetic boundaries between them to separate them into discrete phylogenetic clusters. To detect such postulated genetic boundaries among the E. coli bacteria, we determined the ratios of homologous genes that have identical nucleotide sequences between pairs of strains by the method as reported previously for Salmonella [75]. The overall scales of differences among the profiled ratios (Supplementary Table 1) were consistent with the relative genetic distances revealed on the phylogenetic tree among the bacteria (see Fig. 3). Similar to the Salmonella lineages [68, 75], the E. coli strains well separated on the phylogenetic tree had low ratios of homologous genes with zero nucleotide sequence degeneracy between them, mostly below 10% like in Salmonella (Supplementary Table 1), demonstrating the existence of genetic boundaries that circumscribe the bacteria into discrete clusters. Such remarkable genomic divergence among the E. coli strains suggests that they may also have large numbers of genes different from one another, analysis of which may lead to novel insights into the evolution of different E. coli lineages, especially regarding the emergence of nascent pathogens from their commensal ancestors.

Profiling novel genes and probing the potential pan-genome

We annotated the genomes of the 25 sequenced E. coli strains. We first identified genes that are also present in strain K12 MG1655 (Supplementary Table 2), and then profiled genes that are not present in MG1655 nor in one or more of the 25 E. coli isolates (Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Figure 1). We found that a given strain may have hundreds of genes not present in other E. coli strains, further demonstrating enormous diversity of the commensal E. coli populations. Such large numbers of specific genes will certainly make an E. coli strain biologically distinct from other E. coli lineages, especially in terms of their contributions to the human health, including their potentials to benefit the host or to rise as novel pathogens. In any case, a plastic genomic construction would be a prerequisite for the E. coli bacteria to readily accept foreign genes and become a unique lineage.

To validate the postulation that the E. coli genome is more amenable than those of some closely related bacteria to accept lateral genes and diverge, we probed the pan-genomes of E. coli and Salmonella and compared them. Comparison of 62 E. coli complex strains (including the 25 fresh E. coli isolates and the 37 reference E. coli complex strains) and 45 representative Salmonella strains revealed remarkable differences in their pan-genomes: whereas the 45 Salmonella strains had 2959 shared genes and 9338 total non-redundant genes, the 52 E. coli complex strains had only 1884 shared genes but as many as 17,335 total non-redundant genes (Fig. 4), giving an impression of an “open pan-genome” that may keep growing in size by accepting additional novel genes.

Low E. coli diversity in colorectal cancer patients

The apparent tendency of low E. coli diversity in CRC patients pointed to a possibility of the bacteria as potential pathogens, directly or indirectly contributing to CRC, such as by creating an unhealthy intestinal microenvironment through suppressing or even purging beneficial E. coli lineages. To test such a postulation, we set up a series of growth competition assays and inspected the E. coli strains isolated from CRC patients for their competing growth abilities in rich (LB broth) or nutrient-limited (M9) medium with E. coli strains isolated from healthy subjects.

In such experiments, we co-cultured an E. coli strain isolated from a CRC patient with two E. coli strains isolated from two separate healthy subjects and detected the genomic cleavage patterns by the CTAG tetra-nucleotide sequence recognizing endonuclease XbaI in the end co-cultures (See details in Methods). XbaI and other CTAG recognizing endonucleases, such as BlnI/AvrII, SpeI and NheI, have rare cleavage sites in E. coli and the overall cleavage patterns are unique to bacteria of a particular phylogenetic cluster [26, 31, 76, 77]. In experiment set 1, for example, we included an E. coli strain from a CRC patient (ccpm6195) and one strain each from two university students (ccpm5172 and ccpm5602). After 10 days of diluted cultures by daily 100-fold dilution of 30 μl overnight culture into 3 ml fresh medium, we found that the three E. coli strains grew equally well in LB broth but the situation was dramatically different in M9 medium (Fig. 5). As shown in Fig. 5, the E. coli strain from a CRC patient (ccpm6195; lane 2) and the two E. coli strains from two university students (ccpm5172 and ccpm5602; lane 3 and 4, respectively) had distinct XbaI cleavage patterns, so they could be distinguished unambiguously. The mixture of the three strains showed all bandings of lanes 2, 3 and 4 on day 0 (Fig. 5, lane 5) when they were mixed immediately prior to genomic extraction. After incubation for 10 days in LB broth, the end mixture culture showed a similar growth pattern (Fig. 5, lane 6) to that of the initial mixture (Fig. 5, lane 5), whereas the end mixture culture of the three strains in M9 medium showed only the XbaI cleavage pattern of ccpm6195 (the E. coli strain from a CRC patient; Fig. 5, lane 7), demonstrating that ccpm6195 may have greater capability of harnessing the hardly available nutrient in the M9 medium, although direct or indirect suppression of the E. coli strains from healthy individuals by the E. coli strain from a CRC patient cannot be ruled out.

Growth competition among E. coli isolates from CRC patients and healthy controls. Lanes: 1, λ ladder as molecular size marker; 2, ccpm6195; 3, ccpm5172; 4, ccpm5062; 5, a mixture of ccpm6195, 5172 and 5062 before the competition assay; 6, a mixture of ccpm6195, 5172 and 5062 cultured in LB broth at the end of the competition assay; 7, a mixture of ccpm6195, 5172 and 5062 cultured in M9 medium at the end of the competition assay. Remarkably, after culture for 10 days in M9 medium, only ccpm6195 (see lane 7, the E. coli strain from a CRC patient, in which the genomic cleavage pattern is indistinguishable with that in lane 2) survived. These growth competition assays demonstrate that when nutrient was ample (as in LB broth), the three E. coli strains did not interfere with one another for growth; but when the nutrient was limited, the E. coli strains from a CRC patient had greater capabilities to compete for nutrient to grow

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated the associations of high phylogenetic diversity of E. coli with health, with the diversity going up with age from children through young adults to longevity seniors. We believe that the assumed commensal E. coli bacteria, i.e., those that are not associated with apparent intestinal or extra-intestinal infections, are the products of co-evolution with the human host, adapting to different microenvironments in the human intestine and providing a variety of beneficial functions to their host. Low diversity therefore may mean the absence of several such beneficial functions, making the host vulnerable to certain unhealthy factors and hence susceptible to some diseases such as CRC. Although the observed association between low E. coli diversity and CRC does not exclude the possibility that the conditions that lead to low E. coli diversity are conditions that lead to colorectal cancer as having been extensively discussed with a focus on changes in the intestinal microbiome [78, 79], we are inclined to believe low E. coli diversity, caused by the purging capabilities of certain non-benign E. coli lineages, to be a novel risk factor for CRC based on the results we obtained in this study, especially the phylogenetically distinct and biologically aggressive E. coli lineages.

These findings provoke a key question: what is the nature of the diversity? Are the diverse E. coli strains some randomly picked members of a wide spectrum of continual genetic variants collectively called a species of E. coli or do they represent discrete phylogenetic clusters? For a definite answer to this health-relevant question, we analyzed the collected E. coli isolates and dissected the diversity among them. The collected 2280 E. coli isolates were all assumed to be commensals, because they were not related to intestinal or extra-intestinal illnesses in the healthy participants. At least for this study, we also deemed the E. coli isolates from the CRC patients to be commensals, because etiological associations of E. coli with CRC had not been established.

Using a combination of genomic analysis methods, including PFGE to determine the global physical structure of the bacterial genome [25], CTAG tetra-nucleotide profiling by the use of CTAG sequence recognizing endonucleases to distinguish different phylogenetic clusters [80, 81], and whole genome sequence comparisons to identify genes common to the bacteria in comparison and those present only in a subset of the bacteria, we delineated these bacteria into discrete genotypes. It was the use of the combined methods that made this work possible. One of the core techniques used in this study was I-CeuI cleavage profiling by PFGE, which can categorize bacteria into genus or sub-genus phylogenetic levels unambiguously and intuitively [27, 28, 82]. Although the next generation sequencing techniques have been developing extremely rapidly, with continuously increasing capacity and radically dropping cost, sequencing of 2280 strains is still an enormous task, let alone the fact that all the thousands of bacterial genomes would have to be completely finished without a single gap or sequencing error for this kind of global genome comparisons. Additionally, distinguishing three co-cultured E. coli strains without labeling any of them by additional manipulations such as antimicrobial resistance markers can be conveniently and unambiguously achieved only by CTAG tetra-nucleotide sequence profiling; in fact, no any other molecular methods currently available can fulfill this task.

All the results demonstrate that the great diversity revealed among the 2280 E. coli strains was due to the divergence of the bacteria into discrete phylogenetic clusters, not a continual spectrum of genetic variants, over evolutionary times, during which the bacteria in the phylogenetic clusters accumulated genomic variations independently and became genetically isolated from one another by genetic boundaries. The absence of genetic continuum, or rather continuum of genetic variations, among the highly related Salmonella subgroup I pathogens has been previously proven [32, 33, 68, 75], but it is the first time for the E. coli bacteria to be delineated into independent phylogenetic lineages that did not have detectable continuum of genetic variations among them. Therefore, we think it reasonable to treat different genotypes of E. coli as different bacteria or as bacteria of highly related but distinct species, especially considering the finding that a given E. coli strain may have hundreds of genes not found in any other E. coli strains analyzed in this study (see Supplementary Table 3). As such, the commonly assumed commensal E. coli bacteria with large numbers of genes specific to only one or a few genotypes may accomplish a wide range of different biological activities for the benefit of their host and lack of any of them may mean the lack of certain beneficial functions to contribute to the health of the host, leading to the vulnerability of the host to diseases, e.g., CRC.

In fact, recent discoveries on the genetic diversity and population structure of E. coli have encouraged investigators to associate certain phylogenetic groups or clonal complexes with human diseases [23, 83,84,85]. Such “intra-” E. coli diversity has mostly been treated as genetic differences within a “single” bacterial species. However, at least in views of bacterial genetics and pathogenicity, the evolutionary divergence between E. coli K12 and O157:H7 should have separated them into entirely different bacteria, which, with the former being a harmless commensal and the latter a deadly pathogen [56, 86], may have over a thousand genes different between them. In the analysis of the fresh E. coli isolates in this study, we profiled the genetic variations among them and found that the levels of overall genetic divergence among them were similar to that of E. coli K12 and O157:H7. The large numbers of novel genes specific to the individual E. coli genotypes would render the bacteria different abilities or preference to adapt to a broad range of micro-niches in the gut environment. Additionally, the genetic separation of the E. coli bacteria by clear-cut boundaries strongly indicates their non-overlapping environmental settings in the intestinal lumen of a host. Indeed, the co-existence of genetically diverse E. coli lineages in healthy people would be best explained by their inability or unnecessity to purge each other, very possibly due to their difference in resource requirement. Therefore the very low diversity of the E. coli isolates from CRC patients in sharp contrast with the high diversity of the bacteria in the healthy individuals is indicative of the health significance of E. coli diversity to the host. Notably, the E. coli isolates from the CRC patients suppressed the growth of E. coli isolates from healthy controls when the nutrients were limited, suggesting their greater growth capabilities, which may in turn result in unhealthy microenvironments in the intestine and facilitate the carcinogenesis of the intestinal tissues.

It is a very interesting observation that the E. coli diversity increased with age, which may reflect a general scenario of dynamic E. coli diversification during the life time of the host. But how is the diversity reached?

Bacteria acquire genetic novelty and diverge by two major mechanisms, including incorporating large exogenous DNA segments, e.g., prophages, genomic islands, etc., and accumulating nucleotide substitutions, with the former being mostly acute to divert the evolutionary direction and the latter usually chronic to make gradual genomic ameliorations in a chronological way [31, 87, 88]. Comparisons between E. coli K12 and O157:H7 as well as among the genotypes indicate that the acquisition of large exogenous DNA segments is highly frequent in evolution and the events may happen almost instantly. However, the final acceptance of the acquired DNA segments may take time for genomic ameliorations toward eventual adaptation. If one assumes that bacterial genomic ameliorations take place at similar rates among different bacteria [89, 90], the different E. coli lineages, with genetic distances between them being similar to that as between S. typhi and S. typhimurium (see Fig. 3), would be estimated to have a divergence time of 35–50 thousand years [91]. Therefore, the striking diversity of commensal E. coli revealed in this study would be a result of gradual colonization of a host by pre-existing E. coli lineages, rather than de novo creation of nascent E. coli lineages through divergence. Indeed, the phylogenetic divergence would require evolutionary times that are much longer than the lifespan of a human host. The colonization process may take certain lengths of time, which may partly explain why E. coli in people with advanced ages may have higher genomic diversity than in junior people. Although high genomic diversity of the E. coli populations is positively correlated with health status, we currently have no direct evidence yet to show whether the low E. coli diversity in the CRC patients might be the consequence or an etiologic factor of the disease.

Conclusions

Commensal E. coli are diverse and the diversity increases in the healthy hosts with age from children through young adults to longevity seniors, suggesting that the coexistence of multiple E. coli lineages may help create and maintain a microbial environment that is beneficial to the host. The diversity is due to a high number of discrete phylogenetic clusters rather than continual genetic variations spanning a wide spectrum of the E. coli bacteria. E. coli isolates from CRC patients had growth advantages over those from healthy individuals, suggesting their potential pathogenic roles.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Abbreviations

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- Genotypes:

-

Genome types

- NJ method:

-

Neighbor-joining method

- PFGE:

-

Pulsed field gel electrophoresis

References

Kaper JB, Nataro JP, Mobley HL. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2(2):123–40.

Nataro JP, Kaper JB. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11(1):142–201.

Russo TA, Johnson JR. Proposal for a new inclusive designation for extraintestinal pathogenic isolates of Escherichia coli: ExPEC. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(5):1753–4.

Johnson JR, Russo TA. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli as agents of diverse non-urinary tract extraintestinal infections. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(6):859–64.

Johnson JR, Russo TA. Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli: “the other bad E coli”. J Lab Clin Med. 2002;139(3):155–62.

Johnson JR, Russo TA. Molecular epidemiology of extraintestinal pathogenic (uropathogenic) Escherichia coli. Int J Med Microbiol. 2005;295(6–7):383–404.

Miquel S, Peyretaillade E, Claret L, de Vallee A, Dossat C, Vacherie B, et al. Complete genome sequence of Crohn's disease-associated adherent-invasive E. coli strain LF82. PLoS One. 2010;5(9):1–16.

Krause DO, Little AC, Dowd SE, Bernstein CN. Complete genome sequence of adherent invasive Escherichia coli UM146 isolated from Ileal Crohn's disease biopsy tissue. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(2):583.

Nash JH, Villegas A, Kropinski AM, Aguilar-Valenzuela R, Konczy P, Mascarenhas M, et al. Genome sequence of adherent-invasive Escherichia coli and comparative genomic analysis with other E. coli pathotypes. BMC Genomics. 2011;11:667.

Jin Y, Tang S, Li W, Ng SC, Chan MW, Sung JJ, et al. Hemolytic E. coli promotes colonic tumorigenesis in females. Cancer Res. 2016;76(10):2891–900.

Bonnet M, Buc E, Sauvanet P, Darcha C, Dubois D, Pereira B, et al. Colonization of the human gut by E. coli and colorectal cancer risk. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(4):859–67.

Gagniere J, Bonnin V, Jarrousse AS, Cardamone E, Agus A, Uhrhammer N, et al. Interactions between microsatellite instability and human gut colonization by Escherichia coli in colorectal cancer. Clin Sci. 2017;131(6):471–85.

Buc E, Dubois D, Sauvanet P, Raisch J, Delmas J, Darfeuille-Michaud A, et al. High prevalence of mucosa-associated E. coli producing cyclomodulin and genotoxin in colon cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56964.

Raisch J, Rolhion N, Dubois A, Darfeuille-Michaud A, Bringer MA. Intracellular colon cancer-associated Escherichia coli promote protumoral activities of human macrophages by inducing sustained COX-2 expression. Lab Investig. 2015;95(3):296–307.

Kohoutova D, Smajs D, Moravkova P, Cyrany J, Moravkova M, Forstlova M, et al. Escherichia coli strains of phylogenetic group B2 and D and bacteriocin production are associated with advanced colorectal neoplasia. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:733.

Raisch J, Buc E, Bonnet M, Sauvanet P, Vazeille E, de Vallee A, et al. Colon cancer-associated B2 Escherichia coli colonize gut mucosa and promote cell proliferation. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(21):6560–72.

Wassenaar TM. E. coli and colorectal cancer: a complex relationship that deserves a critical mindset. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2018;44(5):619–32.

Brenner DJ, Fanning GR, Skerman FJ, Falkow S. Polynucleotide sequence divergence among strains of Escherichia coli and closely related organisms. J Bacteriol. 1972;109(3):953–65.

Brenner DJ, Fanning GR, Steigerwalt AG, Orskov I, Orskov F. Polynucleotide sequence relatedness among three groups of pathogenic Escherichia coli strains. Infect Immun. 1972;6(3):308–15.

Ochman H, Selander RK. Standard reference strains of Escherichia coli from natural populations. J Bacteriol. 1984;157(2):690–3.

Ochman H, Selander RK. Evidence for clonal population structure in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81(1):198–201.

Ochman H, Whittam TS, Caugant DA, Selander RK. Enzyme polymorphism and genetic population structure in Escherichia coli and Shigella. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129(Pt 9):2715–26.

Whittam TS, Ochman H, Selander RK. Multilocus genetic structure in natural populations of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80(6):1751–5.

Liu SL, Sanderson KE. A physical map of the salmonella typhimurium LT2 genome made by using XbaI analysis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174(5):1662–72.

Liu SL. Physical mapping of salmonella genomes. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;394:39–58.

Liu SL, Hessel A, Sanderson KE. The XbaI-BlnI-CeuI genomic cleavage map of salmonella typhimurium LT2 determined by double digestion, end labelling, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175(13):4104–20.

Liu SL, Sanderson KE. I-CeuI reveals conservation of the genome of independent strains of salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1995;177(11):3355–7.

Liu SL, Hessel A, Sanderson KE. Genomic mapping with I-Ceu I, an intron-encoded endonuclease specific for genes for ribosomal RNA, in salmonella spp., Escherichia coli, and other bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(14):6874–8.

Liu SL, Schryvers AB, Sanderson KE, Johnston RN. Bacterial phylogenetic clusters revealed by genome structure. J Bacteriol. 1999;181(21):6747–55.

Liu SL, Hessel A, Sanderson KE. The XbaI-BlnI-CeuI genomic cleavage map of salmonella enteritidis shows an inversion relative to salmonella typhimurium LT2. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10(3):655–64.

Tang L, Liu WQ, Fang X, Sun Q, Zhu SL, Wang CX, et al. CTAG-containing cleavage site profiling to delineate salmonella into natural clusters. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e103388.

Tang L, Mastriani E, Zhou YJ, Zhu S, Fang X, Liu YP, et al. Differential degeneration of the ACTAGT sequence among salmonella: a reflection of distinct nucleotide amelioration patterns during bacterial divergence. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):10985.

Tang L, Zhu S, Mastriani E, Fang X, Zhou YJ, Li YG, Johnston RN, Guo Z, Liu GR, Liu SL. Conserved intergenic sequences revealed by CTAG-profiling in salmonella: thermodynamic modeling for function prediction. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43565. https://doi.org/10.41038/srep44356.

Feng Y, Xu HF, Li QH, Zhang SY, Wang CX, Zhu DL, et al. Complete genome sequence of salmonella enterica serovar pullorum RKS5078. J Bacteriol. 2012;194(3):744.

Liu WQ, Feng Y, Wang Y, Zou QH, Chen F, Guo JT, et al. Salmonella paratyphi C: genetic divergence from salmonella choleraesuis and pathogenic convergence with salmonella typhi. PLoS One. 2009;4(2):e4510.

Riley M, Abe T, Arnaud MB, Berlyn MK, Blattner FR, Chaudhuri RR, et al. Escherichia coli K-12: a cooperatively developed annotation snapshot--2005. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(1):1–9.

Crossman LC, Chaudhuri RR, Beatson SA, Wells TJ, Desvaux M, Cunningham AF, et al. A commensal gone bad: complete genome sequence of the prototypical enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli strain H10407. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(21):5822–31.

Liu B, Hu B, Zhou Z, Guo D, Guo X, Ding P, et al. A novel non-homologous recombination-mediated mechanism for Escherichia coli unilateral flagellar phase variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(10):4530–8.

Mangiamele P, Nicholson B, Wannemuehler Y, Seemann T, Logue CM, Li G, et al. Complete genome sequence of the avian pathogenic Escherichia coli strain APEC O78. Genome Announc. 2013;1(2):e0002613.

Ogura Y, Ooka T, Iguchi A, Toh H, Asadulghani M, Oshima K, et al. Comparative genomics reveal the mechanism of the parallel evolution of O157 and non-O157 enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(42):17939–44.

Oshima K, Toh H, Ogura Y, Sasamoto H, Morita H, Park SH, et al. Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of the wild-type commensal Escherichia coli strain SE11 isolated from a healthy adult. DNA Res. 2008;15(6):375–86.

Ahmed SA, Awosika J, Baldwin C, Bishop-Lilly KA, Biswas B, Broomall S, et al. Genomic comparison of Escherichia coli O104:H4 isolates from 2009 and 2011 reveals plasmid, and prophage heterogeneity, including Shiga toxin encoding phage stx2. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e48228.

Geddes RD, Wang X, Yomano LP, Miller EN, Zheng H, Shanmugam KT, et al. Polyamine transporters and polyamines increase furfural tolerance during xylose fermentation with ethanologenic Escherichia coli strain LY180. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(19):5955–64.

Avasthi TS, Kumar N, Baddam R, Hussain A, Nandanwar N, Jadhav S, et al. Genome of multidrug-resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain NA114 from India. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(16):4272–3.

Toh H, Oshima K, Toyoda A, Ogura Y, Ooka T, Sasamoto H, et al. Complete genome sequence of the wild-type commensal Escherichia coli strain SE15, belonging to phylogenetic group B2. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(4):1165–6.

Iguchi A, Thomson NR, Ogura Y, Saunders D, Ooka T, Henderson IR, et al. Complete genome sequence and comparative genome analysis of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli O127:H6 strain E2348/69. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(1):347–54.

Hochhut B, Wilde C, Balling G, Middendorf B, Dobrindt U, Brzuszkiewicz E, et al. Role of pathogenicity island-associated integrases in the genome plasticity of uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain 536. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61(3):584–95.

Chen SL, Hung CS, Xu J, Reigstad CS, Magrini V, Sabo A, et al. Identification of genes subject to positive selection in uropathogenic strains of Escherichia coli: a comparative genomics approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(15):5977–82.

Touchon M, Hoede C, Tenaillon O, Barbe V, Baeriswyl S, Bidet P, et al. Organised genome dynamics in the Escherichia coli species results in highly diverse adaptive paths. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(1):e1000344.

Welch RA, Burland V, Plunkett G 3rd, Redford P, Roesch P, Rasko D, et al. Extensive mosaic structure revealed by the complete genome sequence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(26):17020–4.

Chaudhuri RR, Sebaihia M, Hobman JL, Webber MA, Leyton DL, Goldberg MD, et al. Complete genome sequence and comparative metabolic profiling of the prototypical enteroaggregative Escherichia coli strain 042. PLoS One. 2010;5(1):e8801.

Lu S, Zhang X, Zhu Y, Kim KS, Yang J, Jin Q. Complete genome sequence of the neonatal-meningitis-associated Escherichia coli strain CE10. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(24):7005.

Zhou Z, Li X, Liu B, Beutin L, Xu J, Ren Y, et al. Derivation of Escherichia coli O157:H7 from its O55:H7 precursor. PLoS One. 2010;5(1):e8700.

Xiong Y, Wang P, Lan R, Ye C, Wang H, Ren J, et al. A novel Escherichia coli O157:H7 clone causing a major hemolytic uremic syndrome outbreak in China. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e36144.

Bergholz TM, Wick LM, Qi W, Riordan JT, Ouellette LM, Whittam TS. Global transcriptional response of Escherichia coli O157:H7 to growth transitions in glucose minimal medium. BMC Microbiol. 2007;7:97.

Perna NT, Plunkett G 3rd, Burland V, Mau B, Glasner JD, Rose DJ, et al. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nature. 2001;409(6819):529–33.

Yang F, Yang J, Zhang X, Chen L, Jiang Y, Yan Y, et al. Genome dynamics and diversity of Shigella species, the etiologic agents of bacillary dysentery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(19):6445–58.

Nie H, Yang F, Zhang X, Yang J, Chen L, Wang J, et al. Complete genome sequence of Shigella flexneri 5b and comparison with Shigella flexneri 2a. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:173.

Le Bars H, Bousarghin L, Bonnaure-Mallet M, Jolivet-Gougeon A, Barloy-Hubler F. Complete genome sequence of the strong mutator salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype Heidelberg strain B182. J Bacteriol. 2012;194(13):3537–8.

McClelland M, Sanderson KE, Spieth J, Clifton SW, Latreille P, Courtney L, et al. Complete genome sequence of salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium LT2. Nature. 2001;413(6858):852–6.

Chiu CH, Tang P, Chu C, Hu S, Bao Q, Yu J, et al. The genome sequence of salmonella enterica serovar Choleraesuis, a highly invasive and resistant zoonotic pathogen. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(5):1690–8.

Fricke WF, Mammel MK, McDermott PF, Tartera C, White DG, Leclerc JE, et al. Comparative genomics of 28 salmonella enterica isolates: evidence for CRISPR-mediated adaptive sublineage evolution. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(14):3556–68.

Thomson NR, Clayton DJ, Windhorst D, Vernikos G, Davidson S, Churcher C, et al. Comparative genome analysis of salmonella Enteritidis PT4 and salmonella Gallinarum 287/91 provides insights into evolutionary and host adaptation pathways. Genome Res. 2008;18(10):1624–37.

McClelland M, Sanderson KE, Clifton SW, Latreille P, Porwollik S, Sabo A, et al. Comparison of genome degradation in Paratyphi a and Typhi, human-restricted serovars of salmonella enterica that cause typhoid. Nat Genet. 2004;36(12):1268–74.

Deng W, Liou SR, Plunkett G 3rd, Mayhew GF, Rose DJ, Burland V, et al. Comparative genomics of salmonella enterica serovar Typhi strains Ty2 and CT18. J Bacteriol. 2003;185(7):2330–7.

Delcher AL, Bratke KA, Powers EC, Salzberg SL. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(6):673–9.

Delcher AL, Harmon D, Kasif S, White O, Salzberg SL. Improved microbial gene identification with GLIMMER. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(23):4636–41.

Tang L, Li Y, Deng X, Johnston RN, Liu GR, Liu SL. Defining natural species of bacteria: clear-cut genomic boundaries revealed by a turning point in nucleotide sequence divergence. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:489.

Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular cloning. 3rd ed. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001.

Gauthier A, Turmel M, Lemieux C. A group I intron in the chloroplast large subunit rRNA gene of Chlamydomonas eugametos encodes a double-strand endonuclease that cleaves the homing site of this intron. Curr Genet. 1991;19(1):43–7.

Marshall P, Lemieux C. Cleavage pattern of the homing endonuclease encoded by the fifth intron in the chloroplast large subunit rRNA-encoding gene of Chlamydomonas eugametos. Gene. 1991;104(2):241–5.

Picard B, Garcia JS, Gouriou S, Duriez P, Brahimi N, Bingen E, et al. The link between phylogeny and virulence in Escherichia coli extraintestinal infection. Infect Immun. 1999;67(2):546–53.

Johnson JR, Delavari P, Kuskowski M, Stell AL. Phylogenetic distribution of extraintestinal virulence-associated traits in Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis. 2001;183(1):78–88.

Johnson JR, Stell AL. Extended virulence genotypes of Escherichia coli strains from patients with urosepsis in relation to phylogeny and host compromise. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(1):261–72.

Tang L, Wang CX, Zhu SL, Li Y, Deng X, Johnston RN, et al. Genetic boundaries to delineate the typhoid agent and other salmonella serotypes into distinct natural lineages. Genomics. 2013;102(4):331–7.

McClelland M, Bhagwat AS. Biased DNA repair. Nature. 1992;355(6361):595–6.

McClelland M, Jones R, Patel Y, Nelson M. Restriction endonucleases for pulsed field mapping of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15(15):5985–6005.

Marchesi JR, Dutilh BE, Hall N, Peters WH, Roelofs R, Boleij A, et al. Towards the human colorectal cancer microbiome. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e20447.

Marchesi JR, Adams DH, Fava F, Hermes GD, Hirschfield GM, Hold G, et al. The gut microbiota and host health: a new clinical frontier. Gut. 2016;65(2):330–9.

Tang L, Liu RW, Jin G, Zhao EY, Liu GR, Liu SL. Spontaneous modulation of a dynamic balance between bacterial genomic stability and mutability: roles and molecular mechanisms of the genetic switch. Science China. 2014;57(3):1–5.

Bhagwat AS, McClelland M. DNA mismatch correction by very short patch repair may have altered the abundance of oligonucleotides in the E. coli genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20(7):1663–8.

Liu GR, Liu WQ, Johnston RN, Sanderson KE, Li SX, Liu SL. Genome plasticity and ori-ter rebalancing in salmonella typhi. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23(2):365–71.

Whittam TS, Ochman H, Selander RK. Geographic components of linkage disequilibrium in natural populations of Escherichia coli. Mol Biol Evol. 1983;1(1):67–83.

Chaudhuri RR, Henderson IR. The evolution of the Escherichia coli phylogeny. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12(2):214–26.

Clermont O, Bonacorsi S, Bingen E. Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66(10):4555–8.

Blattner FR, Plunkett G 3rd, Bloch CA, Perna NT, Burland V, Riley M, et al. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science (New York, NY). 1997;277(5331):1453–74.

Lawrence JG, Ochman H. Amelioration of bacterial genomes: rates of change and exchange. J Mol Evol. 1997;44(4):383–97.

Marri PR, Golding GB. Gene amelioration demonstrated: the journey of nascent genes in bacteria. Genome. 2008;51(2):164–8.

Mira A, Ochman H. Gene location and bacterial sequence divergence. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19(8):1350–8.

Ochman H, Elwyn S, Moran NA. Calibrating bacterial evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(22):12638–43.

Kidgell C, Reichard U, Wain J, Linz B, Torpdahl M, Dougan G, et al. Salmonella typhi, the causative agent of typhoid fever, is approximately 50,000 years old. Infect Genet Evol. 2002;2(1):39–45.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants who provided fecal specimens for their cooperation.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC31600001) and a National Postdoctoral Fellowship of China (2016 M600266) to LT; a Heilongjiang Innovation Endowment Award for graduate studies (YJSCX2012-214HLJ) to YJZ; grants of National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC30970078, 81971910) to GRL; and grants of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC81030029, 81271786, 81671980, 81871623) to SLL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LT carried out the experimental work and conducted genomic sequence analyses; YJZ and SLZ were involved in genomic sequence analyses; GDL, HZ, MFZ, ZL, XYC, HNL, ZL, ZRG, XQM and XL collected bacterial strains and were involved in experiments; XH, WQL, CXW, DDZ, JJL, BQY were involved in experiments; LBD and LW performed bacterial identification; YGL, JBZ, RNJ, JZ and GRL participated in data analysis and discussions; LT, YJZ and SLL conceived and designed the study and wrote the manuscript. The authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by The Ethics Committee, Harbin Medical University, and all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. We obtained a written informed consent from each participant or their guardian, consistent with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki on Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects.

Consent for publication

All authors have read the manuscript and agreed to its content. This work is original and is not currently under consideration by another journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Percentages of common genes with identical nucleotide sequences among the fresh E. coli isolates from healthy individuals.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Profile of genes in the 25 E. coli isolates in common with E. coli K12 MG1655.

Additional file 3:

Table S3. Profiles of genes not present in K12 MG1655 but present in one or more of the 25 E. coli isolates.

Additional file 4: Figure S1.

Genomic comparison of sequenced fresh E. coli isolates with strain K12 MG1655 to show the presence or absence of K12 MG1655 in the sequenced fresh E. coli isolates. Genes present in any of the sequenced fresh E. coli isolates but not in K12 MG1655 are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, L., Zhou, YJ., Zhu, S. et al. E. coli diversity: low in colorectal cancer. BMC Med Genomics 13, 59 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-020-0704-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-020-0704-3