Abstract

Background

In China, although the ALV eradication program and the MD vaccination strategy greatly reduce the disease burdens caused by the infection of ALV and MDV, the frequent emergence of novel ALV-K or vvMDV in the vaccinated chicken flock challenges the current control strategies for both diseases.

Results

In Guangdong Province, an indigenous chicken flock was infected with neoplastic disease. Hematoxylin–eosin staining of the tissues showed the typical characteristics of MDV and classical ALV infection. The PCR and sequencing data demonstrated that the identified MDV was clustered into a very virulent MDV strain endemic in domestic chickens in China. Moreover, subgroups ALV-A and ALV-K were efficiently recovered from two samples. The full genome sequence revealed that the ALV-K isolate was phylogenetically close to the ALV TW3593 isolate from Taiwan Province.

Conclusions

A co-infection of vvMDV with multiple ALV subgroups emerged in a chicken flock with neoplastic disease in Guangdong Province. The co-infection with different subgroups of ALV with vvMDV in one chicken flock poses the risk for the emergence of novel ALVs and heavily burdens the control strategy for MDV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Avian leukosis virus (ALV) and Marek’s disease virus (MDV) are the most causative agents for neoplastic disease in chickens [1]. ALV is currently classified into seven subgroups (A-E, J and K) in chickens based on the antigenicity of its envelope protein [2]. Infection with avian leukosis virus subgroup A (ALV-A) or ALV-B generally results in classical lymphocytic leukemia, while ALV-J infection mainly causes myeloid leukosis and vascular neoplasms [3,4,5]. ALV-C and ALV-D are rare in clinical cases, whereas ALV-K is a novel subtype of ALV recently identified in indigenous Asian chicken flocks [6,7,8,9,10,11]. Different from ALV-A, B, C, D, J and K, ALV-E belongs to endogenous ALV. MDV can be clustered into different pathotypes, including mild (m), virulent (v), very virulent (vv) and very virulent plus (vv+) strains. Marek’s disease (MD) caused by MDV is mainly characterized by lymphoproliferative disease in chickens with multiple neuritis or malignant tumors of the internal organs [12]. Except for inducing tumors, the infection of ALV or MDV also causes immunosuppression, which significantly affects the sustaining development of the poultry industry globally [13]. In China, although the ALV eradication program and the MD vaccination strategy greatly reduce the disease burdens caused by the infection of ALV and MDV, the frequent emergence of the novel ALV-K or the very virulent MDV (vvMDV) in the vaccinated chicken flock challenges the current control strategies for both diseases [2, 13, 14]. In this study, an outbreak of vvMDV infection in a vaccinated indigenous chicken flock co-infected with ALV-A, ALV-J and ALV-K was reported in China.

Results

Clinical symptoms and pathological changes

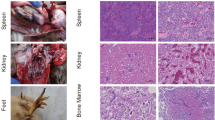

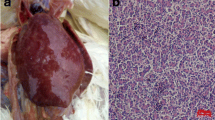

In 2017, a chicken farm in Guangdong Province suffered from neoplastic disease. The histopathological assay demonstrated that a large number of multinuclear tumor cells were observed in the liver tissue with pathological mitotic features (Fig. 1a), and many lymphocytic leukemia cells were found in the liver tissues with vacuolated nuclei (Fig. 1b). The histopathological assay indicated that these chickens might be infected with ALV and MDV.

Co-infection of MDV with ALV-A, J and K

To identify the potential causative agents, the tissue specimens (liver or spleen) from the diseased chickens were randomly collected, and the genomic DNA was extracted from these samples. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to detect oncogenic pathogens: ALV-A, ALV-B, ALV-J, ALV-K, Reticuloendotheliosis virus (REV) and MDV using the primers listed in Table 1. As described in Fig. 2, all the samples tested were positive for MDV in PCR but negative for REV and ALV-B. For the detection of ALV-A, ALV-J and ALV-K, the positive rate in 10 diseased chicken samples was 90, 80 and 90%, respectively (Fig. 2). Notably, all the PCR data were confirmed by sequencing the PCR products. These data clearly demonstrated that the diseased chicken flock was co-infected with MDV, ALV-A, ALV-J and ALV-K.

A Venn diagram showing the PCR detection results of Marek’s disease virus (MDV) and three subgroups of avian leukosis virus (ALV) in the diseased chickens. The red box shows chickens infected with MDV; the blue box shows chickens infected with ALV-A; the yellow box shows chickens infected with ALV-J; the green box shows chickens infected with ALV-K; the overlaps of different boxes show the co-infection status of the diseased chickens

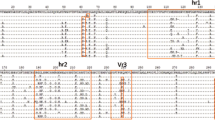

The identified MDVs belonged to vvMDV strains endemic in China

To further investigate whether the MDV detected in the diseased chicken flock is a vaccine strain or vvMDV strain, the meq, gB and pp38 genes were amplified from these samples by PCR and analyzed. The sequence assay for the PCR products revealed that the meq, gB and pp38 genes of the MDV (named GD) were 100% identical to the domestic vvMDV strain GX0101, which has been reportedly circulating on chicken farms in China for a long time (Fig. 1c) (gB and pp38 data not shown). The finding of vvMDV in this vaccinated chicken flock challenges the current MD vaccination strategy in China.

ALV-A and ALV-K were efficiently isolated from the clinical samples

To further isolate ALVs in the diseased chickens, the homogenates of the PCR-positive samples for ALV-A, ALV-J and ALV-K were inoculated into DF1 cells. After several blind passages of the inoculated DF1 cells, the indirect immunofluorescent assay (IFA) and PCR were used to detect the isolation. Finally, one ALV-A isolate and one ALV-K isolate, named GD-A (Genbank accession No. MK951945) and GD-K (Genbank accession No. MK941182), respectively, were isolated from these samples and confirmed by IFA using monoclonal antibody (mAb) 5D3 against p27 (Fig. 3) and PCR with subgroup-specific primers (data not shown). The gp85 sequence of the GD-A isolate showed 94.4–99.1% identity with those reference ALV-A strains deposited in NCBI and lower than 86.9% similarity with other subgroups of ALV, which was confirmed by the phylogenetic analysis as described in Fig. 1d.

The GD-K ALV-K isolate phylogenetically resembled the TW3593 isolate derived in Taiwan

Since the ALV-K is a novel subtype of ALV recently identified in indigenous Asian chicken flocks [7, 8], to understand the molecular characteristics of the ALV-K isolate GD-K, the full genome of the GD-K was amplified by three overlapping rounds of PCR and sequenced. Sequence data showed that the complete genome was 7483 bp in length and had more than 97.6% identity with the ALV-K reference strains deposited in NCBI, except for JS11C (92.7%) (Fig. 4a). In addition, the gp85 sequence of GD-K showed 94.8–99.6% homology with the ALV-K reference strains and lower than 87.4% with other subgroups of ALVs (Fig. 4b). Notably, both the intact genome and gp85 sequence of the GD-K isolate demonstrated a close evolutionary relationship with the ALV-K isolate TW3593 from Taiwan (Fig. 4a and Fig. 4b). Further analysis of the long terminal repeat (LTR) sequence showed that the LTR of GD-K grouped together with TW-3593, CZ1401, CZ1402, GDFX0601, GDFX0602 and GDFX0603, as well as the ALV-E subgroup in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 4c).

Discussion

MDV and ALVs have caused severe economic losses to the poultry industry worldwide [17]. Notably, the frequent co-infection of MDV with ALVs or REV has undoubtedly become a great threat to the healthy development of the poultry industry [17,18,19,20]. In this study, vvMDV and ALV-K were first identified in a chicken flock in southern China. In the field, vvMDV or ALV-K single infection has been reported previously, which could cause immunosuppression in chickens and make them more susceptible to other pathogens. It should also be noted that ALV-K is frequently undetectable due to its poor replication ability [8, 10, 20,21,22]. The frequent transportation and communication of the indigenous chickens in southern China and the difficulties in detecting ALV-K were some other possible reasons for co-infection status [20].

In summary, a co-infection of vvMDV with multiple ALV subgroups was identified in a chicken flock with neoplastic disease in Guangdong Province. Moreover, subgroups ALV-A and ALV-K were efficiently isolated from two samples. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of co-infection of vvMDV with the novel ALV subgroup ALV-K. Notably, although the positive rate of ALV-J in these diseased chickens was 80% for PCR, ALV-J could not be efficiently isolated. This interesting finding indicated that co-infections with ALV-A or ALV-K, even vvMDV, might impact the replication of ALV-J. However, how these pathogens interact with each other remains to be further studied. In the case of ALV-A, resistant loci of tvar1, tvar2, tvar3, and tvar4 have been found in some inbred lines of White Leghorn [23, 24]. In addition, single nucleotide polymorphism variants within tva receptor genes in some Chinese chicken breeds have been reported and animals with certain tva alleles are resistant to ALV-A infection [25, 26]. Notably, a recent research has showed that the novel ALV-K shares its tva cell receptor with ALV-A [27]. Thus, the tva receptors in the chicken flock are possibly associated with ALV-A and ALV-K infection status in this study as well. In short, future study should also focus on the polymorphisms of tva receptors in different indigenous chicken breeds in China, test the susceptibility of these indigenous chickens to ALV-A and ALV-K infections, and breed chickens resistant to ALV-A and ALV-K.

Conclusions

The co-infection of vvMDV with different subgroups of ALV identified in a chicken flock poses a risk for the emergence of novel ALVs and burdens the control strategy for MD and highlights the significance of epidemiological monitoring for similar co-infection in indigenous chicken flocks in China.

Methods

Clinical samples

Layer chickens that were 150 days old and vaccinated with MDV and suffering from neoplastic disease with about 10% neoplastic incidence and 5% mortality were obtained from a large chicken farm in Guangdong Province, China. The owner of the farm gave permission to include ten diseased chickens in this study. Tumor nodules were found on the surface of the organs and skin from these diseased chickens. All experiments complied with institutional animal care guidelines and were approved by the University of Yangzhou Animal Care Committee.

Histopathological assay

A histopathological assay was conducted as previously described to examine the tissues [16]. Briefly, the livers from the diseased chickens were fixed using 10% formalin buffer, dehydrated in alcohol, and embedded in paraffin. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was then performed, and microscopic changes were observed by light microscopy.

PCR detection for oncogenic pathogens

Genomic DNA from the tissues of diseased chickens was first extracted and detected with specific primers (Table 1) for the oncogenic pathogens MDV, ALV and REV by PCR [15, 16].

Virus isolation

The homogenates of the PCR-positive tissue samples were filtered through a 0.22 μm filter and inoculated into DF1 cells for 2 h. Then, fresh Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS) was used for replacement. The supernatant of the cell culture was passed for three serial passages (5–7 days for each passage), and then the infected cells were screened for ALV by PCR and IFA.

Indirect immunofluorescence assay

The infected DF1 cells were fixed with chilled acetone:ethanol solution (3:2) for 5 min and washed once with PBS. Then, they were incubated with the ALV-p27-specific mAb 5D3 for 45 min at 37 °C [28]. After three washes with PBS, the cells were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody for another 45 min. After three washes with PBS, the cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope.

Sequence analysis

For PCR, the gB, pp38 and meq genes were amplified as described [16]. For amplification of ALV and REV genes, 50 μl of reaction volume was used, which consisted of 10 μl of 5 × SF PCR buffer, 1 μl dNTP mixture, 2 μl of each primer, 1 μl of Phanta Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Vazyme, Nanjing, China), 32 μl of ddH2O, and 2 μl of the DNA template. The PCR programs for the pp38 and meq genes were 94 °C for 3 min, 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min 30 s, and then 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR products were separated by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and then sequenced by Genscript (Nanjing, China). All sequences were aligned with Lasergene 7 and phylogenetically analyzed with MEGA 6.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ALV:

-

Avian leukosis virus

- ALV-A:

-

Avian leukosis virus subgroup A;

- DMEM:

-

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- FITC:

-

Fluorescein isothiocyanate

- IFA:

-

Indirect immunofluorescent assay

- LTR:

-

Long terminal repeat

- MD:

-

Marek’s disease

- MDV:

-

Marek’s disease virus

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- REV:

-

Reticuloendotheliosis virus

- v:

-

Virulent

- vv:

-

Very virulent

- vv+:

-

Very virulent plus

- vvMDV:

-

Very virulent MDV

References

Wen Y, Huang Q, Yang C, Pan L, Wang G, Qi K, Liu H. Characterizing the histopathology of natural co-infection with Marek's disease virus and subgroup J avian leucosis virus in egg-laying hens. Avian Pathol. 2018;47(1):83–9.

Payne LN, Nair V. The long view: 40 years of avian leukosis research. Avian Pathol. 2012;41(1):11–9.

Ono M, Tsukamoto K, Tanimura N, Haritani M, Kimura KM, Suzuki G, Okuda Y, Sato S. An epizootic of subcutaneous tumors associated with subgroup a avian leukosis/sarcoma virus in young layer chickens. Avian Dis. 2004;48(4):940–6.

Venugopal K. Avian leukosis virus subgroup J: a rapidly evolving group of oncogenic retroviruses. Res Vet Sci. 1999;67(2):113–9.

Cui Z, Du Y, Zhang Z, Silva RF. Comparison of Chinese field strains of avian leukosis subgroup J viruses with prototype strain HPRS-103 and United States strains. Avian Dis. 2003;47(4):1321–30.

Adkins HB, Blacklow SC, Young JA. Two functionally distinct forms of a retroviral receptor explain the nonreciprocal receptor interference among subgroups B, D, and E avian leukosis viruses. J Virol. 2001;75(8):3520–6.

Wang X, Zhao P, Cui Z. Identification of a new subgroup of avian leukosis virus isolated from Chinese indigenous chicken breeds. Bing Du Xue Bao. 2012;28(6):609–14 (in Chinese, with English abstract).

Cui N, Su S, Chen Z, Zhao X, Cui Z. Genomic sequence analysis and biological characteristics of a rescued clone of avian leukosis virus strain JS11C1, isolated from indigenous chickens. J Gen Virol. 2014;95(Pt 11:2512–22.

Li X, Lin W, Chang S, Zhao P, Zhang X, Liu Y, Chen W, Li B, Shu D, Zhang H, et al. Isolation, identification and evolution analysis of a novel subgroup of avian leukosis virus isolated from a local Chinese yellow broiler in South China. Arch Virol. 2016;161(10):2717–25.

Shao H, Wang L, Sang J, Li T, Liu Y, Wan Z, Qian K, Qin A, Ye J. Novel avian leukosis viruses from domestic chicken breeds in mainland China. Arch Virol. 2017;162(7):2073–6.

Su Q, Li Y, Li W, Cui S, Tian S, Cui Z, Zhao P, Chang S. Molecular characteristics of avian leukosis viruses isolated from indigenous chicken breeds in China. Poult Sci. 2018;97(8):2917–25.

Davison AJ, Eberle R, Ehlers B, Hayward GS, McGeoch DJ, Minson AC, Pellett PE, Roizman B, Studdert MJ, Thiry E. The order Herpesvirales. Arch Virol. 2009;154(1):171–7.

Zhou J, Zhao GL, Wang XM, Du XS, Su S, Li CG, Nair V, Yao YX, Cheng ZQ. Synergistic viral replication of Marek's disease virus and avian Leukosis virus subgroup J is responsible for the enhanced pathogenicity in the superinfection of chickens. Viruses. 2018;10(5):271.

Li T, Xie J, Lv L, Sun S, Dong X, Xie Q, Liang G, Xia C, Shao H, Qin A, Ye J. A chicken liver cell line efficiently supports the replication of ALV-J possibly through its high level viral receptor and efficient protein expression system. Vet Res. 2018;49(1):41.

Davidson I, Borovskaya A, Perl S, Malkinson M. Use of the polymerase chain reaction for the diagnosis of natural infection of chickens and turkeys with Marek's disease virus and reticuloendotheliosis virus. Avian Pathol. 1995;24(1):69–94.

Zhuang X, Zou H, Shi H, Shao H, Ye J, Miao J, Wu G, Qin A. Outbreak of Marek's disease in a vaccinated broiler breeding flock during its peak egg-laying period in China. BMC Vet Res. 2015;11:157.

Davidson I, Borenstein R. Multiple infection of chickens and turkeys with avian oncogenic viruses: prevalence and molecular analysis. Acta Virol. 1999;43(2–3):136–42.

Bao KY, Zhang YP, Zheng HW, Lv HC, Gao YL, Wang JF, Gao HL, Qi XL, Cui HY, Wang YQ, et al. Isolation and full-genome sequence of two reticuloendotheliosis virus strains from mixed infections with Marek's disease virus in China. Virus Genes. 2015;50(3):418–24.

Buscaglia C. Mixed infections of Marek's disease and reticuloendotheliosis viruses in layer flocks in Argentina. Avian Dis. 2013;57(2 Suppl):569–71.

Li H, Wang P, Lin L, Shi M, Gu Z, Huang T, Mo ML, Wei T, Zhang H, Wei P. The emergence of the infection of subgroup J avian leucosis virus escalated the tumour incidence in commercial yellow chickens in southern China in recent years. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2019;66(1):312–6.

Zhao Z, Rao M, Liao M, Cao W. Phylogenetic analysis and pathogenicity assessment of the emerging recombinant subgroup K of avian leukosis virus in South China. Viruses. 2018;10(4):194.

Lv L, Li T, Hu M, Deng J, Liu Y, Xie Q, Shao H, Ye J, Qin A. A recombination efficiently increases the pathogenesis of the novel K subgroup of avian leukosis virus. Vet Microbiol. 2019;231:214–7.

Reinišová M, Plachý J, Trejbalová K, Šenigl F, Kučerová D, Geryk J, Svoboda J, Hejnar J. Intronic deletions that disrupt mRNA splicing of the tva receptor gene result in decreased susceptibility to infection by avian sarcoma and leukosis virus subgroup a. J Virol. 2012;86(4):2021–30.

Elleder D, Melder DC, Trejbalova K, Svoboda J, Federspiel MJ. Two different molecular defects in the Tva receptor gene explain the resistance of two tvar lines of chickens to infection by subgroup a avian sarcoma and leukosis viruses. J Virol. 2004;78(24):13489–500.

Liao C, Chen S, Chen W, Liu Y, Sun B, Li H, Zhang H, Qu H, Wang J, Shu D, Xie Q. Single nucleotide polymorphism variants within tva and tvb receptor genes in Chinese chickens. Poult Sci. 2014;93(10):2482–9.

Chen W, Liu Y, Li H, Chang S, Shu D, Zhang H, Chen F, Xie Q. Intronic deletions of tva receptor gene decrease the susceptibility to infection by avian sarcoma and leukosis virus subgroup a. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9900.

Přikryl D, Plachý J, Kučerová D, Koslová A, Reinišová M, Šenigl F, Hejnar J. The novel avian leukosis virus subgroup K shares its cellular chicken receptor with subgroup A. J Virol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00580-19.

Qian K, Liang Y, Yin L, Shao H, Ye J, Qin A. Development and evaluation of an immunochromatographic strip for rapid detection of capsid protein antigen p27 of avian leukosis virus. J Virol Methods. 2015;221:115–8.

Acknowledgements

We thanks for Dr. Jianjun Zhang (Sinopharm Yangzhou VAC Biological Engineering Co.Ltd) for kindly helping us collect the clinical samples.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key Research & Development (R&D) Plan (2018YFD0500106, 2016YFD0501605), NCFC-RCUK-BBSRC (Grant No. 31761133002 and BB/R012865/1), the Key Laboratory of Prevention and Control of Biological Hazard Factors (Animal Origin) for Agrifood Safety and Quality (26116120), the Research Foundation for Talented Scholars in Yangzhou University and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions. The funding bodies did not play direct roles in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JY and AQ conceived and designed the experiments. TL, JX, GL, DR and SS performed the experiments. TL, AQ, HS, WG and JY analyzed the data. TL, JX, GL, QX and LL contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. TL and JY contributed to the writing of the manuscript. TL and JY prepared the figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The diseased chickens with tumor were kindly provided by the farm owner for diagnostics. All experiments complied with institutional animal care guidelines and were approved by the Animal Care Committee of Yangzhou University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, T., Xie, J., Liang, G. et al. Co-infection of vvMDV with multiple subgroups of avian leukosis viruses in indigenous chicken flocks in China. BMC Vet Res 15, 288 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-019-2041-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-019-2041-3