Abstract

Background

Bovine tuberculosis (BTB) is caused by Mycobacterium bovis, which belongs to the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Mycobacterium bovis have been described to be responsible of most cases of bovine tuberculosis. Although M. tuberculosis, M. africanum and non-complex mycobacteria were isolated from cattle.

In Morocco, so far, no molecular studies were conducted to characterize the strains responsible of BTB. The present study aims to characterize M. bovis in Morocco.

The present study was conducted in slaughterhouses in Rabat and El Jadida. Samples were collected from 327 slaughtered animals with visible lesions suggesting BTB.

Results

A total of 225 isolates yielded cultures, 95% (n = 215) of them were acid-fast (AF). Sixty eight per cent of the AF positive samples were confirmed as tuberculous mycobacteria (n = 147), 99% of these (n = 146) having RD9 and among the latter, 98% (n = 143) positive while 2% (n = 3) negative for RD4

A total of 134 samples were analyzed by spoligotyping of which 14 were in cluster and with 41 different spoligotypes, ten of them were new patterns (23%). The most prevalent spoligotypes were SB0121, SB0265, and SB0120, and were already identified in many other countries, such as Algeria, Spain, Tunisia, the United States and Argentina.

Conclusion

The shared borders between Algeria and Morocco, in addition to the previous importation of cattle from Europe and the US could explain the similarities found in M. bovis spoligotypes. On the other hand, the desert of Morocco could be considered as an efficient barrier preventing the introduction of BTB to Morocco from West Central and East Africa. Our findings suggest a low level endemic transmission of BTB similar to other African countries. However, more research is needed for further knowledge about the transmission patterns of BTB in Morocco.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bovine tuberculosis (BTB) is a chronic granulomatous caseous-necrotising inflammatory disease that mainly affects the lungs and their draining lymph nodes, it can also affect other organs, depending on the route of infection [1,2,3]. BTB is caused by Mycobacterium bovis, which belongs to the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC). M. bovis has the particular ability to infect a wide range of host species other than cattle (livestock, wildlife and pets) and humans, [3, 4], however, cattle remain the most important reservoir for M. bovis [5]. There exist important wildlife reservoirs like the badger (Meles meles), the Possum (Trichosurus vulpecula) [4].

M. bovis can be transmitted between animals by inhalation of aerosols and the ingestion of contaminated food. The transmission is enhanced by many risk factors, mostly related to intensive livestock system [6]. The transmission of M. bovis to humans occurs by consumption of unpasteurized infected raw milk and by the contact with infected cattle [7].

While BTB is still occurring in some developed countries in low prevalence [8,9,10] because of a wildlife reservoir [11] i.e. badgers in the UK [12], this zoonosis is endemic in many of the developing countries, who lack the financial resources to control this disease. Bovine tuberculosis is highly prevalent in many African countries [13, 14], where it causes economic losses by its effects on animal health and productivity and by international trade restrictions. [15]. Bovine tuberculosis is also a zoonosis and, consequently, considered as a public health issue [1, 16, 17].

In Morocco, the agriculture sector is of key importance to the economy, representing approximately 14% of total gross domestic product (GDP) (75bn MAD/ €6.6bn) and approximately 7% of exports (2009). Livestock represents 38% of the total agriculture sector GDP [18]. Both extensive and intensive livestock production systems exist in Morocco, with local, crossbred and imported breeds, mostly Holstein. Local breeds have been shown to be more resistant to the disease [14, 19]. Bovine tuberculosis is an endemic zoonosis in Morocco. The last national survey based on skin tuberculin test was conducted in 2004 and showed an individual prevalence of 18% and a herd prevalence of 33% [20]. Furthermore, a cross-sectional tuberculin study was conducted in the Sidi Kacem area in Morocco in 2012 showing an individual prevalence of 20.4% and a herd prevalence of 57.7% [19].

Officially, skin test and slaughter is the current control strategy applied in Morocco; however this strategy is not fully applied as it is not respected; in addition, there is no systematic BTB screening of cattle at a national level [21].

In a review published by Muller et al. in 2013, the proportion of zoonotic human tuberculosis (TB) among all TB cases was estimated at 1.4% for the non-African countries, and at 2.8% in Africa [22]. The highest prevalence were found to be 13.8% and 7% respectively in Mexico [23] and in Uganda [24]. However, the World Health Organisation states a worldwide median prevalence of 3.1% of M. bovis among human TB patients [25]. Even if those prevalence values are mostly low, Muller et al., Pérez-Lago et al. and Navarro, and García-de-Viedma highlight the major consequences of TB due to M. bovis on certain groups of the population, and report a potential underestimation of the prevalence of zoonotic human TB [22, 25].

The phylogeny of MTBC showed recently that the strains found in animals belong to a single lineage which showed the deletion of the “Region of Difference” 9 (RD9) [22, 26]. Indeed, M. bovis is the most recent strain in his lineage showing the deletion of RD4 [27].

Molecular deletion typing had been found to be an important tool to differentiate M. bovis from the other strains of the MTBC [28]. Pattern of presence or absence of these RDs would allow a discrimination among MTBC strains [28,29,30].

Currently there is no data available in Morocco about the molecular characterization of BTB and the prevalence of MTBC among slaughtered cattle. The aim of the present study was to characterize the strains of MTBC which are responsible for BTB among the slaughtered cattle in Morocco.

Methods

Study area and sample collection

The study was conducted in two slaughterhouses in Morocco, one in Rabat and another in EL Jadida, which are two coastal cities separated by 200 km. The cattle slaughtered in these two slaughterhouses come from the rural areas surrounding the two cities and also from many other areas of the country. Individual information of every animal, such as gender, age, breed, and the possible origin were recorded in our database, as well as the date of sampling. The sample collection was performed in Rabat from March to July 2015 and in El Jadida from June 2014 to April 2015.

The samples were conveyed to the Veterinary and Agriculture Institute (IAV) in Rabat and stored in −20 °C until their treatment.

Tissue preparation, culture

Prior to treatment, samples were thawed overnight at 4 °C. Subsequently, samples were desiccated to remove adipose tissue, and 5 g of the desiccated lesions were mixed with sterilized sand and 10 ml of phenol red. The solution (7.5 ml) was placed in a 15 ml conic tube, 2.5 ml of NaOH 1 N was added at room temperature for 10 min, and then HCl 6 N was added for sample neutralization. As a final step, the tube was centrifuged for 25 min at 3500 rpm.

The supernatant was discarded and pellet was distributed in two of the four pre-tested culture media: Lowenstein-Jensen (LJ), LJ with glycerol (LJG) or pyruvate (LJP) and Herrold according to the availability in the laboratory. Cultures were incubated for 12 weeks at 37 °C and observed daily for growing colonies during the first week then weekly from the second week onwards.

All the grown cultures were deactivated by adding a loopful of mycobacterium colonies to 1 ml of sterilized water contained in small tubes. The samples were then inactivated for 1 h at 90 °C.

Determination of MTBC and deletion typing

Mycobacterium molecular characterization was performed using Multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The PCR was performed in the TB laboratory at Swiss TPH. We performed first MrpoB PCR in order to differentiate MTC and NTM as described earlier [31]. Deletion analysis by PCR was used to differentiate M. bovis and M. tuberculosis from other species of the MTBC by assessing the presence or absence of Regions of Difference 9 and 4 (RD). The analysis was carried out as previously described [13, 28].

Spoligotyping

Spoligotyping was performed as previously described [32]. Spoligotyping patterns were defined according to the SITVIT WEB database [33] and to Mycobacterium bovis molecular typing database [34]. All the patterns which were not found in the two databases were submitted as new patterns; new spoligotype numbers were assigned to them.

Results

Cattle information

In the present study, a total number of 8658 animals were examined. Three hundred and twenty seven animal presented gross visible lesions (3.7%) and were cultured, 66% (n = 215) of the total sampled animals were analysed by Ziehl-Neelsen(ZN), 68% (n = 147) of the latter were ZN positive and heat-killed for further molecular typing.

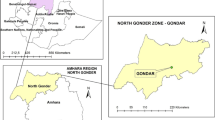

Figure 1 represents the geographic distribution of the samples (Fig. 1). While the age and gender distribution, in addition to the localization of the lesions sampled are shown in the Tables 1 and 2. The majority of the lesions were localised in the lymph nodes and the lungs (Table 2).

The majority of the sampled animals were males between 1 and 3 years and females more than 3 years (Table 1).

MrpoB PCR

A total of 68% (n = 147) of the 215 samples which were AF positive were confirmed as MTBC strains using MrpoB PCR. Thirty two per cent (n = 69) of animals were negative for MrpoB.

Deletion typing

The samples confirmed as MTBC strains were all positive to RD9 deletion typing and then confirmed to be not M. tuberculosis strains. A total of 144 (1.7%) of the samples were confirmed to be M. bovis as they were positive to the RD4 pcr. Three samples were negative for RD4.

Out of the total of the confirmed M. bovis samples, 30% were female while 70% were male. The predominant breed in the positive animals was Crossbreed prime Holstein.

Spoligotyping

A total of 136 analysed samples were lacking spacers 39 to 43. Forty one different spoligopatterns were found. The most frequent patterns were SB0121, SB0265, SB0120, with frequencies of 24.3% (n = 33). 16.9% (n = 23), 9.6% (n = 13) respectively. They were shown to belong to BOV-1 family. Two other spoligotypes were found in 9 and 6 samples respectively, SB0125 and SB0869. Three spoligotype patterns had no SIT reference on the SITVIT database and were designated as orphan. Ten isolates presented nine undescribed spoligotypes, which were submitted to M. bovis website (www.mbovis.org) (Table 3). The discrimination power of spoligotyping, calculated using Hunter and Gaston’s formula was D = 0.9057 [35].

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the molecular characterization of bovine tuberculosis among cattle in Morocco. The prevalence of the gross visible lesions suggesting BTB in Rabat and El Jadida slaughterhouses (3.7%) was low compared to the prevalence found previously using tuberculin skin test in the last national survey performed in 2004 [20]. This prevalence was close to those observed in Mali (1.8%) and in Algeria (3.6%).

Surprisingly, no non-tuberculous mycobacteria was found, while in the African context, among slaughterhouse gross visible lesions, 3.3% in Mali [36], and 9% in Burkina Fasso [37] were confirmed as non-tuberculous mycobacteria. This was also observed in Chadian slaughtered cattle [38, 39].

Almost 52.4% of the overall sample size was confirmed to be M. bovis, three samples were negative to RD4. While two spoligotypes were typical for the caprae family, the third sample was a new spoligotype. Studies in other Countries (e.g. Nigeria, Ethiopia) found M. tuberculosis in cattle [40], whereas in Morocco, remarkably, we didn’t find this MTBC species in our samples.

The most predominant spoligotype pattern found in Morocco is SB0121, belonging to the family BOV 1, this spoligopattern was already reported in Algeria [41], in Tunisia [42] and in Spain [43]. The second most frequent spoligotype was SB0265 which was reported as the second most frequent in the United States from a set of strains collected between 1989 and 2013 [44], in addition, this spoligotype was isolated in Tunisia from a strain coming from Morocco [33], and was also reported in many European countries [45, 46], as well as in Taiwan [47]. The spoligopattern SB0120 had the frequency of 11.7% in our sample size and was reported previously in France from a sample originating from Morocco (SITVIT database), it was also reported in many African countries like Algeria [41], Tunisia [42] and Zambia [48] as well as in Argentina and Spain [43, 49]. Our study shows no similar spoligotype pattern with Mali, indicating that the Sahara desert and the long distance between cattle rearing areas (cattle are only kept until a Latitude of 12 degrees in Mali) seem to be an effective barrier for the transmission of M. bovis and/or that there is probably little trade of cattle between Morocco and Mali [36].

Two spoligotypes of three samples belonged to the M. caprae family, of which one was found as well in M.bovis database as SB0866, this spoligotype was already reported in Spain from one goat, one cattle and one pig in 2011 [50].

The similarities found in some spoligopatterns between Morocco and Algeria could be explained by the shared borders between the two countries, in addition some patterns found in Morocco were previously reported in the United States and in Argentina, two countries from where Morocco have previously imported cattle.

Spoligotypes of African 1 and African 2 clonal complexes were not found among our characterized isolates [51, 52]. African 1 is localized in West and Central Africa, and African 2 is localized in East Africa, consequently, the desert of Morocco could be considered as a potential efficient barrier preventing the introduction of BTB to Morocco from West, Central and East Africa.

The relatively low prevalence of proven M. bovis infection in two Moroccan abattoirs has to be interpreted with caution. Firstly, the abattoir prevalence reflects more the prevalence in young bulls and old cows rather than the whole population. Secondly, not all granuloma yielded a bacteriological isolate, hence the true prevalence may be much higher than the one observed. Overall, our findings reflect rather the epidemiological situation of a low level endemic transmission similar to other African countries rather than the one of a peri-urban intensive system [53, 54]. More research is needed to further characterize the ongoing transmission patterns of bovine tuberculosis in view of the development of a locally adapted elimination strategy of bovine tuberculosis in Morocco [55].

Conclusion

This study presents the first molecular characterization of BTB isolates from Moroccan cattle. M. bovis represented a high amount of granulomatous lesions detected in the abattoirs of Rabat and El Jadida. Spoligotype suggests a link of Moroccan BTB to Europe, rather than to Africa, highlighting then the potential of the Moroccan desert barrier for BTB introduction to Morocco from sub-Saharan Africa. Further investigations of BTB strains using new molecular techniques such as whole genome sequencing are needed to clarify more the potential links between Moroccan BTB strains and those of Europe and other African countries.

Abbreviations

- BTB:

-

Bovine tuberculosis

- LJ:

-

Lowenstein Jensen

- LJG:

-

Lowenstein Jensen with glycerol

- LJP:

-

Lowenstein Jensen with pyruvate

- MTBC:

-

Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex

- NTM:

-

Non-tuberculous mycobacteria

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- RD:

-

Region of difference

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- ZN:

-

Ziehl-Neelsen

References

Ayele WY, Neill SD, Zinsstag J, Weiss MG, Pavlik I. Bovine tuberculosis: an old disease but a new threat to Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis Off J Int Union Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8(8):924–37.

Domingo M, Vidal E, Marco A. Pathology of bovine tuberculosis. Res Vet Sci. 2014;97(Suppl):S20–9.

Pesciaroli M, Alvarez J, Boniotti MB, Cagiola M, Di Marco V, Marianelli C, et al. Tuberculosis in domestic animal species. Res Vet Sci. 2014;97(Suppl):S78–85.

Palmer MV. Mycobacterium Bovis: characteristics of wildlife reservoir hosts. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2013;60(Suppl 1):1–13.

Amanfu W. The situation of tuberculosis and tuberculosis control in animals of economic interest. Tuberculosis. 2006;86(3–4):330–5.

Goodchild AV, Clifton-Hadley RS. Cattle-to-cattle transmission of Mycobacterium Bovis. Tuberc Edinb Scotl. 2001;81(1–2):23–41.

Dankner WM, Davis CE. Mycobacterium Bovis as a significant cause of tuberculosis in children residing along the United States-Mexico border in the Baja California region. Pediatrics. 2000;105(6):E79.

Aranaz A, Liébana E, Mateos A, Dominguez L, Vidal D, Domingo M, et al. Spacer oligonucleotide typing of Mycobacterium Bovis strains from cattle and other animals: a tool for studying epidemiology of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34(11):2734–40.

Haddad N, Ostyn A, Karoui C, Masselot M, Thorel MF, Hughes SL, et al. Spoligotype diversity of Mycobacterium Bovis strains isolated in France from 1979 to 2000. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(10):3623–32.

Smith NH, Dale J, Inwald J, Palmer S, Gordon SV, Hewinson RG, et al. The population structure of Mycobacterium Bovis in great Britain: clonal expansion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(25):15271–5.

Collins JD. Tuberculosis in cattle: strategic planning for the future. Vet Microbiol. 2006;112(2–4):369–81.

Delahay RJ, Walker N, Smith GC, Smith GS, Wilkinson D, Clifton-Hadley RS, et al. Long-term temporal trends and estimated transmission rates for Mycobacterium Bovis infection in an undisturbed high-density badger (Meles Meles) population. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141(7):1445–56.

Mwakapuja RS, Makondo ZE, Malakalinga J, Moser I, Kazwala RR, Tanner M. Molecular characterization of Mycobacterium Bovis isolates from pastoral livestock at Mikumi-Selous ecosystem in the eastern Tanzania. Tuberc Edinb Scotl. 2013;93(6):668–74.

Moiane I, Machado A, Santos N, Nhambir A, Inlamea O, Hattendorf J, et al. Prevalence of bovine tuberculosis and risk factor assessment in cattle in rural livestock areas of Govuro District in the southeast of Mozambique. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e91527.

Palmer MV. Mycobacterium bovis Infection in Animals and Humans, 2nd Edition. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(8):1306. https://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1208.060526.

Cosivi O, Grange JM, Daborn CJ, Raviglione MC, Fujikura T, Cousins D, et al. Zoonotic tuberculosis due to Mycobacterium Bovis in developing countries. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4(1):59–70.

Thoen C, Lobue P, de Kantor I. The importance of Mycobacterium Bovis as a zoonosis. Vet Microbiol. 2006;112(2–4):339–45.

Samuelle C. Livestock sector in Morocco. Bord Bia Ir Food Board [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2015 Oct 2]; Available from: http://www.bordbia.ie/industry/manufacturers/insight/alerts/Pages/LivestocksectorinMorocco.aspx?year=2014&wk=28.

Yahyaoui Azami H, Ducrotoy M, Bouslikhane M, Hattendorf J, Thrusfield M, Conde-Alvarez R, et al. The prevalence of ruminant brucellosis and bovine tuberculosis in Sidi Kacem area in Morocco. Press. 2016.

FAO. Principales réalisations depuis l’ouverture de la Représentation de la FAO à Rabat en 1982. 2011 Juillet.

Tuberculose bovine [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2016 Mar 1]. Available from: http://www.onssa.gov.ma/fr/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=181&Itemid=122.

Müller B, Dürr S, Alonso S, Hattendorf J, Laisse CJM, Parsons SDC, et al. Zoonotic Mycobacterium Bovis-induced tuberculosis in humans. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(6):899–908.

Pérez-Guerrero L, Milián-Suazo F, Arriaga-Díaz C, Romero-Torres C, Escartín-Chávez M. Molecular epidemiology of cattle and human tuberculosis in Mexico. Salud Pública México. 2008;50(4):286–91.

Oloya J, Opuda-Asibo J, Kazwala R, Demelash AB, Skjerve E, Lund A, et al. Mycobacteria causing human cervical lymphadenitis in pastoral communities in the Karamoja region of Uganda. Epidemiol Infect. 2008;136(5):636–43.

Pérez-Lago L, Navarro Y, García-de-Viedma D. Current knowledge and pending challenges in zoonosis caused by Mycobacterium Bovis: a review. Res Vet Sci. 2014;97(Suppl):S94–100.

Smith NH, Kremer K, Inwald J, Dale J, Driscoll JR, Gordon SV, et al. Ecotypes of the mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. J Theor Biol. 2006;239(2):220–5.

Smith NH, Gordon SV, de la Rua-Domenech R, Clifton-Hadley RS, Hewinson RG. Bottlenecks and broomsticks: the molecular evolution of Mycobacterium Bovis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4(9):670–81.

Brosch R, Gordon SV, Marmiesse M, Brodin P, Buchrieser C, Eiglmeier K, et al. A new evolutionary scenario for the mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(6):3684–9.

Mostowy S, Cousins D, Brinkman J, Aranaz A, Behr MA. Genomic deletions suggest a phylogeny for the mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(1):74–80.

van Ingen J, de Zwaan R, Dekhuijzen R, Boeree M, van Soolingen D. Region of difference 1 in Nontuberculous mycobacterium species adds a Phylogenetic and taxonomical character. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(18):5865–7.

Malla B, Stucki D, Borrell S, Feldmann J, Maharjan B, Shrestha B, et al. First Insights into the Phylogenetic Diversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Nepal. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2012 ;7(12). [cited 2016 Jan 13]; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3530561/.

Kamerbeek J, Schouls L, Kolk A, van Agterveld M, van Soolingen D, Kuijper S, et al. Simultaneous detection and strain differentiation of mycobacterium tuberculosis for diagnosis and epidemiology. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35(4):907–14.

SITVIT WEB - M. tuberculosis genotyping WorldWide Database Online Consultation : Description [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2016 Jan 13]. Available from: http://www.pasteur-guadeloupe.fr:8081/SITVIT_ONLINE/tools.jsp.

Mycobacterium bovis molecular typing database [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2016 Jan 13]. Available from: http://www.mbovis.org/.

Hunter PR, Gaston MA. Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson’s index of diversity. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26(11):2465–6.

Müller B, Steiner B, Bonfoh B, Fané A, Smith NH, Zinsstag J. Molecular characterisation of Mycobacterium Bovis isolated from cattle slaughtered at the Bamako abattoir in Mali. BMC Vet Res. 2008;4(1):1.

Sanou A, Tarnagda Z, Kanyala E, Zingué D, Nouctara M, Ganamé Z, et al. Mycobacterium Bovis in Burkina Faso: epidemiologic and genetic links between human and cattle isolates. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(10):e3142.

Diguimbaye-Djaibe C, Hilty M, Ngandolo R, Mahamat HH, Pfyffer GE, Baggi F, et al. Mycobacterium Bovis isolates from tuberculous lesions in Chadian zebu carcasses. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(5):769–71.

Ngandolo BNR, Müller B, Diguimbaye-Djaïbe C, Schiller I, Marg-Haufe B, Cagiola M, et al. Comparative assessment of fluorescence polarization and tuberculin skin testing for the diagnosis of bovine tuberculosis in Chadian cattle. Prev Vet Med. 2009;89(1):81.

Gumi B, Schelling E, Berg S, Firdessa R, Erenso G, Mekonnen W, et al. Zoonotic transmission of tuberculosis between pastoralists and their livestock in south-East Ethiopia. EcoHealth. 2012;9(2):139–49.

Sahraoui N, Müller B, Guetarni D, Boulahbal F, Yala D, Ouzrout R, et al. Molecular characterization of Mycobacterium Bovis strains isolated from cattle slaughtered at two abattoirs in Algeria. BMC Vet Res. 2009;5:4.

Lamine-Khemiri H, Martínez R, García-Jiménez WL, Benítez-Medina JM, Cortés M, Hurtado I, et al. Genotypic characterization by spoligotyping and VNTR typing of Mycobacterium Bovis and Mycobacterium Caprae isolates from cattle of Tunisia. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2014;46(2):305–11.

Navarro Y, Romero B, Copano MF, Bouza E, Domínguez L, de Juan L, et al. Multiple sampling and discriminatory fingerprinting reveals clonally complex and compartmentalized infections by M. Bovis in cattle. Vet Microbiol. 2015;175(1):99–104.

Tsao K, Robbe-Austerman S, Miller RS, Portacci K, Grear DA, Webb C. Sources of bovine tuberculosis in the United States. Infect Genet Evol. 2014;28:137–43.

Rodriguez-Campos S, Aranaz A, de Juan L, Sáez-Llorente JL, Romero B, Bezos J, et al. Limitations of Spoligotyping and variable-number tandem-repeat typing for molecular tracing of Mycobacterium Bovis in a high-diversity setting. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(9):3361–4.

Matos F, Cunha MV, Canto A, Albuquerque T, Amado A, Botelho A. Snapshot of Mycobacterium Bovis and Mycobacterium Caprae infections in livestock in an area with a low incidence of bovine tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(11):4337–9.

Chang J-R, Chen Y-Y, Huang T-S, Huang W-F, Kuo S-C, Tseng F-C, et al. Clonal expansion of both modern and ancient genotypes of mycobacterium tuberculosis in southern Taiwan. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43018.

Malama S, Johansen TB, Muma JB, Mwanza S, Djønne B, Godfroid J. Isolation and molecular characterization of Mycobacterium Bovis from Kafue lechwe (Kobus Leche Kafuensis) from Zambia. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2014;46(1):153–7.

Shimizu E, Macías A, Paolicchi F, Magnano G, Zapata L, Fernández A, et al. Genotyping Mycobacterium Bovis from cattle in the central pampas of Argentina: temporal and regional trends. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2014;109(2):236–45.

Rodríguez S, Bezos J, Romero B, de Juan L, Álvarez J, Castellanos E, et al. Mycobacterium Caprae infection in livestock and wildlife. Spain Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(3):532–5.

Müller B, Hilty M, Berg S, Garcia-Pelayo MC, Dale J, Boschiroli ML, et al. African 1, an epidemiologically important clonal complex of Mycobacterium Bovis dominant in Mali, Nigeria, Cameroon, and Chad. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(6):1951–60.

Berg S, Garcia-Pelayo MC, Müller B, Hailu E, Asiimwe B, Kremer K, et al. African 2, a clonal complex of Mycobacterium Bovis epidemiologically important in East Africa. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(3):670–8.

Tschopp R, Hattendorf J, Roth F, Choudhoury A, Shaw A, Aseffa A, et al. Cost estimate of bovine tuberculosis to Ethiopia. In: One Health: The Human-Animal-Environment Interfaces in Emerging Infectious Diseases. Springer; 2012(ISBN: 978-3-642-36888-2). p. 249–268. ; Available from: http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/82_2012_245.

Tschopp R, Schelling E, Hattendorf J, Young D, Aseffa A, Zinsstag J. Repeated cross-sectional skin testing for bovine tuberculosis in cattle kept in a traditional husbandry system in Ethiopia. Vet Rec. 2010;167(7):250–6.

Abakar MF, Yahyaoui Azami H, Justus Bless P, Crump L, Lohmann P, Laager M, et al. (2017) Transmission dynamics and elimination potential of zoonotic tuberculosis in morocco. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11(2):e0005214. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005214.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the veterinarians in the two slaughterhouses of El Jadida and Rabat, for their help and collaboration.

Funding

This study was supported by the EU FP7 ICONZ program (grant agreement n° 221,948), by the local government of Basel-Stadt, Switzerland, and by the IFS scholarship B 5643.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article, and its additional file(s). The data provided shows the original sample name, individual information, in addition to Deletion typing results for all 215 MTBC strains isolated from Morocco, and spoligotype pattern and number for 136 samples which were analyzed by spoligotyping.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HYA: Participated to the acquisition of a part of the funds (IFS grant), participated in the conception and design of the study, culture of Mycobacteria, molecular analysis, statistical analysis, writing of the manuscript. HA: Participated in sample collection. MB: Participated in the conception and design of the study, acquisition of funds, principle supervision in Morocco and intellectual contributions. JB: Participated in the conception and design of the study, Principle supervision of the laboratory work in Morocco (culture of mycobacteria). SR: Participated to the laboratory work in Morocco (culture of mycobacteria). MR: supervision of the molecular analysis in the tuberculosis laboratory in the Swiss TPH. SG: Supervision of the laboratory work in the Swiss TPH, important intellectual contribution. JF: Supervision of the molecular analysis in the tuberculosis laboratory in the Swiss TPH. SB: Supervision of the molecular analysis, and participated to the conception and the design of the study. JZ: Principal supervision of the project, Principle acquisition of the funds, important intellectual contribution. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No ethical consideration was necessary, as the sampling work was part of routine work of meat inspection in the slaughterhouses.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have co competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yahyaoui-Azami, H., Aboukhassib, H., Bouslikhane, M. et al. Molecular characterization of bovine tuberculosis strains in two slaughterhouses in Morocco. BMC Vet Res 13, 272 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-017-1165-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-017-1165-6