Abstract

Background

There is an increased incidence of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) in patients with metabolic syndrome who usually have high levels of serum triglyceride (TG) and low high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C). Plasma atherogenic index (PAI) is the logarithmic ratio of serum TG level to HDL-C and related to cardiovascular diseases. In this study, we aimed to determine the accuracy of PAI in determining renal malignancy in localized renal masses preoperatively.

Methods

Totally 169 patients who were diagnosed with Bosniak III-IV lesions by imaging modalities and treated in our hospital with partial or radical nephrectomy were retrospectively analyzed using institutional renal cancer database between 2013 and 2018. Preoperative images were evaluated by two experienced radiologists. The patients were divided into two groups according to their postoperative pathological diagnosis as malignant or benign tumors. The PAI of each patient was calculated and the statistical significance of PAI in predicting malignancy for renal masses was analyzed using uni- and multivariable analyses.

Results

Of patients, 109 (64.5%) were males and 60 (35.5%) were females with a median age of 61 (33–84) years. Median tumor size was 6.5 (2–18) cm. Pathological diagnosis was malignant in 145 (85.8%) and benign in 24 (14.2%) patients. There was no statistically significant difference in serum TG levels between malignant and benign cases (p > 0.05). The HDL-C levels were significantly lower in malignant cases (p = 0.001). Median PAI value was 0.63 (0.34–1.58) and significantly higher in malignant cases (p = 0.003). The PAI cut-off value for malignancy was ≥0.34. The sensitivity was calculated as 88.2% and specificity as 45.8%, the positive predictive value as 90.8, negative predictive value as 39.3, and odds ratio as 6.37 (95% CI: 2.466–16.458). In multivariable analysis, gender, smoking status, and hypertension had no effect on malignancy, whereas PAI and HDL-C were independent risk factors (p = 0.003 and p = 0.003, respectively). The risk of malignancy was 5.019 times higher, when PAI was > 0.34 (95% CI: 1.744–14.445) in multivariable logistic regression analysis.

Conclusions

The PAI can be used as a predictive tool in suspicion of malignant renal masses. In case of a benign pathology, PAI levels may be encouraging for surgeons for nephron-sparing surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is 2 to 4% of all newly diagnosed tumors in adults [1]. Renal masses are often found incidentally in ultrasonography (USG), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) which are performed to evaluate other pathologies [2]. These are called localized renal masses and, although most of them are malignant in pathological examination, about 20 to 30% of specimens are still diagnosed with benign lesions [3]. Tumor biopsy is the only histological diagnostic method in the preoperative period, particularly in small renal masses. In addition, CT imaging is the standard tool to detec renal masses; however, it is not reliable in distinguishing different histological types of tumors [4]. Also, MRI and USG are helpful in evaluating complex renal masses, although they have some limitations [5, 6]. In a systematic review, overall median diagnostic sensitivity and specificity in predicting RCC were reported as 88% (IQR 81–94%) and as 75% (IQR 51–90%), respectively for CT and as 87.5% (IQR 75.25–100%) and as 89% (IQR 75–96%), respectively [7].

Well-defined risk factors for RCC include tobacco use, obesity, and hypertension (HT). Also, hyperglycemia, hypertrigliseridemia, low high-density lipoprotein HDL cholesterol (HDL-C) levels, and metabolic syndrome with obesity have been shown to be related with RCC [8]. Obesity is a known risk factor for renal cancer. Although lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress have been primarily blamed, the exact underlying biological mechanisms are still unclear [9, 10]. In addition, dyslipidemia has been shown to increase oxidative stress and chronic inflammation and to be associated with insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome [11]. Lipids which are the major cell membrane components promote cell growth and alterations in their concentrations may occur during carcinogenesis [12]. In general, RCC patients with hypertrigliseridemia have a lower progression-free and cancer-specific survival rates [13]. High triglyceride (TG)/HDL-C ratio indicates an atherogenic lipid profile, which is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular diseases [14, 15]. In recent studies, the Plasma Atherogenic Index (PAI) is used as a reliable indicator for cardiovascular diseases [16, 17] and has been shown to be associated with metabolic syndrome and high body weight [18, 19]. The PAI is the logarithmic ratio of the plasma TG to HDL-C levels [log (TG / HDL-C)] [20]. It is a simple calculation without an extra cost.

In the present study, we aimed to determine the accuracy of PAI in determining renal malignancy in localized renal masses preoperatively.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients with renal mass who underwent partial or radical nephrectomy in our hospital between the years 2013 and 2018. Approval was obtained from the institutional Ethics Committee. Patients were selected based on the existence of Bosniak III or IV lesions as evidenced by imaging modalities. Patients with incomplete data for lipid profiles before the operation, missing pre-operative diagnostic images, and those who were already on lipid-lowering agents, such as statin and fenofibrate, were excluded from the study. Metabolic syndrome was not considered an exclusion criterion. Although smoking may disrupt the lipid profile, smoking is a well-defined risk factor for RCC; therefore, it was not considered an exclusion criterion, either. A total of 169 patients who met the inclusion criteria and were randomly selected were included in the study. Two experienced radiologists evaluated preoperative images of the patients. Another experienced radiologist evaluated the images, when the diagnosis of malignancy was suspected. Two experienced uropathologists evaluated postoperative specimens of the patients. The patients were divided into two groups according to their pathological diagnosis as malignant or benign renal tumors. The PAI of each patient was calculated using the formula log [plasma TG level / plasma HDL-C level]. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the predictive factors for malignancy. The role of PAI in predicting malignancy of renal masses was evaluated.

A written informed consent was obtained from each patient. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Number Cruncher Statistical System (NCSS) version 2007 software (NCSS LLC., Kaysville, UT, USA). Descriptive data were expressed in mean and standard deviation (SD), median (min-max), or number and frequency. Normal distribution of the quantitative data was analyzed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The Student’s t-test was used to compare two groups of quantitative variables showing normal distribution and Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare two groups of quantitative variables which did not show normal distribution. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used in comparison of more than two groups of quantitative variables showing normal distribution. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare more than two groups of quantitative variables which did not show normal distribution. The Pearson chi-square test was used to compare the qualitative data. Diagnostic scanning tests including sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) analysis were carried out to determine the predictive value for the parameters. The correlation between age, gender, side, size, and localization of the tumor, smoking status, diabetes mellitus (DM), HT, body mass index (BMI), HDL-C, TG, and PAI and malignancy were evaluated in univariable analyses. The multivariable logistic regression analysis was used in four models to investigate the effect of HDL-C, PAI, and TG on malignancy. In all models, gender, BMI, smoking status, and HT were independent variables, while HDL-C in the first model, PAI in the second model, TG in the third model, and PAI in the fourth model was additionally included. In these analyses, the impact of PAI on malignancy was evaluated alone and combined with HDL-C and TG. The DeLong method of area under curve (AUC) of the ROC curve was conducted to analyze significant differences. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 169 patients, 109 (64%) were males and 60 (36%) were females with a median age of 61 (33–84) years. Pathological diagnosis was a malignant renal lesion in 145 cases (85.8%) and a benign renal lesion in 24 cases (14.2%). The median tumor size was 6.5 (2–18) cm. The mean BMI was 29.00 ± 4.28 kg/m2. The median value of PAI was 0.53 (0.15–1.58) (Table 1). Demographic and tumoral characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1.

There was no statistically significant relationship between malignancy and patient age, side, size, and localization of the tumor, and DM status of the patient. In male patients, malignancy rate was higher than females (p = 0.039). The BMI was significantly higher in malignant patients (p = 0.023). The number of smoker patients and those with HT was significantly higher in malignant group (p = 0.009 and p = 0.026, respectively). Plasma HDL-C levels were significantly lower in malignant cases (p = 0.001). There was no significant difference in plasma TG levels between malignant and benign cases (p > 0.05). The PAI of malignant cases was significantly higher than the PAI of benign cases (p = 0.003) (Table 2).

The ROC curve analysis showed that the cut-off value for malignancy was 0.34. The PAI cut-off value (0.34) had a sensitivity of 88.2% and a specificity of 45.8%. The PPV was 90.8 and NPV was 39.3. The AUC of the ROC curve was 69% and standard error was 5.8%. For the cut-off value of 0.34, the odds ratio was 6.37 (95% CI: 2.466–16.458).

Univariable analysis revealed that significant factors related to malignancy were gender, smoking status, HT, BMI, HDL-C level, and PAI. The effect of these variables was also evaluated by multivariable logistic regression analysis. According to the results of multivariable analyses, the effect of gender, smoking status, and HT on malignancy was not significant. A PAI of ≥0.34 increased the risk of malignancy by 5.019 folds (95% CI: 1.744–14.445) (Table 3 - Model 2). Similarly, low values of HDL-C (F < 55; M < 45) increased the risk of malignancy [5.019 folds (95% CI: 1.744–14.445) in Model 1 and 2.062 (95% CI: 0.738–5.767) in Model 4, respectively] (Table 3).

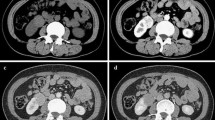

All models predicting malignancy revealed a statistically significant outcomes (p < 0.001, for all). Although the AUC of the ROC curve showed no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05, for all), the highest AUC of the ROC curve was observed in Model 2 which included PAI (Table 3 & Fig. 1). No significant difference was found in PAI between the Fuhrman grades (p > 0.05).

Discussion

In this retrospective study, we showed that PAI and low values HDL-C of the patients with pathologically proven malignant renal tumors were significantly higher, compared to PAI of patients with benign renal lesions. Based on the multivariable logistic regression analysis, the malignancy risk was 4.55 folds higher in the patients with a PAI of > 0.34.

Dobiasova et al. [20] were the first to publish about log (TG/HDL-C) formula which they named the PAI. They found that this ratio was directly proportional to fractional esterification of HDL-C, inversely proportional to the particle size of LDL-C, and there was a direct relation between the PAI and atherosclerosis risk. Later studies showed a correlation between PAI and acute coronary syndrome and other cardiovascular diseases [16, 17].

In an epidemiological study, Haggstrom et al. [21] reported that increased BMI, serum glucose, and TG levels were significant risk factors for renal cancer in male patients, while only increased BMI was found a significant risk factor in female patients. As the relationship between obesity and renal tumors is well-known and obesity has blamed for one of the underlying pathologies for impaired lipid metabolism, a number of studies have attempted to investigate the possible relationship between lipid levels and renal cancer. In the Metabolic Syndrome and Cancer project (Me-Can) examining the relationship between serum TG levels and cancer in patients with metabolic syndrome, a significant correlation was found between TG levels and renal cancer (p = 0.001 RR: 1.96 (1.51–2.46)) [22]. However, in another study conducted by the Vorarlberg Health Monitoring and Promotion Program (VHM&PP) Study Group, increased TG levels were not associated with an increased risk for cancer (p = 0.105 HR:1.27 (0.95–1.69)) [23]. In the Apolipoprotein-related Mortality Risk (AMORIS) study, there was a significant correlation between TG and renal cancer risk (p = 0.001) and there was a negative correlation between total cholesterol and HDL-C and renal cancer risk (p = 0.001 and p = 0.075, respectively) [24]. In our study, although gender, HT, and smoking which are well-known risk factors for renal caner were found to be significant risk factors in the univariable analysis, we found no significant relationship between TG levels and renal cancer (p > 0.05). Although previous studies have shown a correlation between lipid levels and renal cancer, there is no study available in the literature comparing patients with suspected malignancy as assessed by imaging studies and those with a benign pathological diagnosis. In the AMORIS study, there was a significant correlation of the TG/HDL-C ratio with renal cancer, but not with cancer [24]. In this large-scale, comprehensive study, the cut-off value of the log (TG/HDL-C) to prevent cardiovascular diseases was calculated similar to previous studies (0.5) However, in our study, we used a cut-off value of 0.34, which suggested that PA with other variables was a predictor of renal cancer. Despite small sample size in our study, the reason for the discrepancy in our results and AMORIS findings may be due to different cut-off values used. Nonetheless, the use of different cut-off values for cardiovascular diseases and renal cancer is reasonable, since the pathophysiological mechanisms of both diseases are different.

Furthermore, it is well-established that systemic inflammatory response has a negative effect on survival of RCC patients [25]. Vivar et al. [26] reported that inflammation has a significant, negative impact on the prognosis and progression of clear-cell RCC. Systemic inflammation induces some alterations in lipid metabolism [27]. Changes in TG metabolism also affect HDL-C metabolism [28]. These alterations also modify PAI. Since renal malignancy may present with systemic inflammation and lipid metabolism changes, it is reasonable to use PAI to predict malignant renal masses in the preoperative period.

In addition, PAI has been shown to be related with metabolic syndrome and high body weight [18, 19]. Metabolic syndrome characterized by hyperglycemia, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, low HDL-C levels, and abdominal obesity has a strong correlation with RCC [8]. Progression-free and cancer-specific survival in RCC is worse, when TG levels are high [13]. In our study, there was no statistically significant difference between TG levels of malignant and benign cases (p > 0.05). On the other hand, HDL-C levels of malignant cases were found to be significantly lower than benign cases (p = 0.001). Accordingly, PAI of malignant cases were significantly higher than benign cases (p = 0.003). Based on these findings, we believe that, in patients with suspected renal masses on their preoperative radiological images, PAI can be used as an additional predictive tool of malignancy and be helpful for planning the type of the operation (partial or radical nephrectomy).

Limitations

Nonetheless, there are some limitations to this study. First, it was a retrospective, observational study and the inherent retrospective and non-randomized nature might have led to selection bias. Second, only patients of a single center were included and the sample size was small. Third, we evaluated only patients who underwent surgery for renal masses and we were unable to compare symptomatic and incidental cases. These conditions might have also led to selection bias and may be not representative of general population. Nevertheless, our study showed a direct correlation between PAI and malignant renal masses which should be investigated in further large-scale, prospective, multi-center studies.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the incidence of newly diagnosed localized renal masses has been increasing with the routine use of advanced imaging modalities. Our study results suggest that PAI can be used as a predictive tool preoperatively to distinguish benign cases from malignant ones and be encouraging for the surgeons to consider performing nephron-sparing surgery. However, further large-scale, prospective, and multi-center studies are needed to establish a definite conclusion.

Availability of data and materials

All the data supporting our findings is contained in the manuscript. The datasets used and/or analysed in the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MS:

-

Metabolic syndrome

- PAI:

-

Plasma atherogenic index

- RCC:

-

Renal cell carcinoma

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- USG:

-

Ultrasonography

References

Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(1):11–30. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21166.

Dutcher JP. Update on the biology and management of renal cell carcinoma. J Investig Med. 2019;67(1):1-10. https://doi.org/10.1136/jim-2018-000918.

Frank I, Blute ML, Cheville JC, Lohse CM, Weaver AL, Zincke H. Solid renal tumors: an analysis of pathological features related to tumor size. J Urol. 2003;170(6 Pt 1):2217–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000095475.12515.5e.

Pierorazio PM, Hyams ES, Tsai S, Feng Z, Trock BJ, Mullins JK, Johnson PT, Fishman EK, Allaf ME. Multiphasic enhancement patterns of small renal masses (</=4 cm) on preoperative computed tomography: utility for distinguishing subtypes of renal cell carcinoma, angiomyolipoma, and oncocytoma. Urology. 2013;81(6):1265–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2012.12.049.

Israel GM, Hindman N, Bosniak MA. Evaluation of cystic renal masses: comparison of CT and MR imaging by using the Bosniak classification system. Radiology. 2004;231(2):365–71. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2312031025.

Gerst S, Hann LE, Li D, Gonen M, Tickoo S, Sohn MJ, Russo P. Evaluation of renal masses with contrast-enhanced ultrasound: initial experience. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197(4):897–906. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.10.6330.

Vogel C, Ziegelmuller B, Ljungberg B, Bensalah K, Bex A, Canfield S, Giles RH, Hora M, Kuczyk MA, Merseburger AS, Powles T, Albiges L, Stewart F, Volpe A, Graser A, Schlemmer M, Yuan C, Lam T, Staehler M. Imaging in suspected renal-cell carcinoma: systematic review. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2019;17(2):e345-e355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clgc.2018.07.024.

Zhang GM, Zhu Y, Ye DW. Metabolic syndrome and renal cell carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:236. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-12-236.

Don C. Atypical collapse of the right lung simulating combined right upper- and middle-lobe collapse. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1991;42(2):148.

Gago-Dominguez M, Castelao JE, Yuan JM, Ross RK, Yu MC. Lipid peroxidation: a novel and unifying concept of the etiology of renal cell carcinoma (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 2002;13(3):287–93.

Hsieh J, Hayashi AA, Webb J, Adeli K. Postprandial dyslipidemia in insulin resistance: mechanisms and role of intestinal insulin sensitivity. Atheroscler Suppl. 2008;9(2):7–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosissup.2008.05.011.

Vilchez JA, Martinez-Ruiz A, Sancho-Rodriguez N, Martinez-Hernandez P, Noguera-Velasco JA. The real role of prediagnostic high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and the cancer risk: a concise review. Eur J Clin Investig. 2014;44(1):103–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.12185.

Haddad AQ, Jiang L, Cadeddu JA, Lotan Y, Gahan JC, Hynan LS, Gupta N, Raj GV, Sagalowsky AI, Margulis V. Statin use and serum lipid levels are associated with survival outcomes after surgery for renal cell carcinoma. Urology. 2015;86(6):1146–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2015.09.015.

Krintus M, Koziński M, Kuligowska-Prusińska M, Laskowska E, Janiszewska E, Kubica J, Odrowąż-Sypniewska G. The performance of triglyceride to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio in acute coronary syndromes using a diagnostic decision tree. Medical Research Journal. 2015;3(1):13–9.

da Luz PL, Favarato D, Faria-Neto JR Jr, Lemos P, Chagas AC. High ratio of triglycerides to HDL-cholesterol predicts extensive coronary disease. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2008;63(4):427–32.

Zhan Y, Xu T, Tan X. Two parameters reflect lipid-driven inflammatory state in acute coronary syndrome: atherogenic index of plasma, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016;16:96. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-016-0274-7.

Niroumand S, Khajedaluee M, Khadem-Rezaiyan M, Abrishami M, Juya M, Khodaee G, Dadgarmoghaddam M. Atherogenic index of plasma (AIP): a marker of cardiovascular disease. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2015;29:240.

Shen S, Lu Y, Dang Y, Qi H, Shen Z, Wu L, Li F, Yang C, Qiang D, Yang Y, Shui K, Bao Y. Effect of aerobic exercise on the atherogenic index of plasma in middle-aged Chinese men with various body weights. Int J Cardiol. 2017;230:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.12.132.

Pourfarzam M, Zadhoush F, Sadeghi M. The difference in correlation between insulin resistance index and chronic inflammation in type 2 diabetes with and without metabolic syndrome. Adv Biomed Res. 2016;5:153. https://doi.org/10.4103/2277-9175.188489.

Dobiasova M, Frohlich J. The plasma parameter log (TG/HDL-C) as an atherogenic index: correlation with lipoprotein particle size and esterification rate in apoB-lipoprotein-depleted plasma (FER (HDL)). Clin Biochem. 2001;34(7):583–8.

Haggstrom C, Rapp K, Stocks T, Manjer J, Bjorge T, Ulmer H, Engeland A, Almqvist M, Concin H, Selmer R, Ljungberg B, Tretli S, Nagel G, Hallmans G, Jonsson H, Stattin P. Metabolic factors associated with risk of renal cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e57475. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0057475.

Borena W, Stocks T, Jonsson H, Strohmaier S, Nagel G, Bjorge T, Manjer J, Hallmans G, Selmer R, Almquist M, Haggstrom C, Engeland A, Tretli S, Concin H, Strasak A, Stattin P, Ulmer H. Serum triglycerides and cancer risk in the metabolic syndrome and cancer (me-can) collaborative study. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22(2):291–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-010-9697-0.

Ulmer H, Borena W, Rapp K, Klenk J, Strasak A, Diem G, Concin H, Nagel G. Serum triglyceride concentrations and cancer risk in a large cohort study in Austria. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(7):1202–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605264.

Van Hemelrijck M, Garmo H, Hammar N, Jungner I, Walldius G, Lambe M, Holmberg L. The interplay between lipid profiles, glucose, BMI and risk of kidney cancer in the Swedish AMORIS study. Int J Cancer. 2012;130(9):2118–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.26212.

Wu Y, Fu X, Zhu X, He X, Zou C, Han Y, Xu M, Huang C, Lu X, Zhao Y. Prognostic role of systemic inflammatory response in renal cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137(5):887–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-010-0951-3.

de Vivar Chevez AR, Finke J, Bukowski R. The role of inflammation in kidney cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;816:197–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-0348-0837-8_9.

Khovidhunkit W, Kim MS, Memon RA, Shigenaga JK, Moser AH, Feingold KR, Grunfeld C. Effects of infection and inflammation on lipid and lipoprotein metabolism: mechanisms and consequences to the host. J Lipid Res. 2004;45(7):1169–96. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.R300019-JLR200.

de Carvalho JF, Borba EF, Viana VS, Bueno C, Leon EP, Bonfa E. Anti-lipoprotein lipase antibodies: a new player in the complex atherosclerotic process in systemic lupus erythematosus? Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(11):3610–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.20630.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EK: Protocol/project development, Data management, Manuscript writing NK: Protocol/project development, Data management, Statistical analysis, Manuscript writing SD: Data Collection, Data analysis CT: Data Collection, Data analysis ARA: Critical revision of the manuscript for scientific and factual content, Manuscript editing OEY: Critical revision of the manuscript for scientific and factual content, Manuscript editing. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. This study was approved by the Haydarpasa Training and Research Hospital Local Ethics Committee.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Karabay, E., Karsiyakali, N., Duvar, S. et al. Relationship between plasma Atherogenic index and final pathology of Bosniak III-IV renal masses: a retrospective, single-center study. BMC Urol 19, 85 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-019-0514-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-019-0514-0