Abstract

Background

Our understanding of effective perioperative supportive interventions for patients undergoing cystectomy procedures and how these may affect short and long-term health outcomes is limited.

Methods

Randomised controlled trials involving any non-surgical, perioperative interventions designed to support or improve the patient experience for patients undergoing cystectomy procedures were reviewed. Comparison groups included those exposed to usual clinical care or standard procedure. Studies were excluded if they involved surgical procedure only, involved bowel preparation only or involved an alternative therapy such as aromatherapy. Any short and long-term outcomes reflecting the patient experience or related urological health outcomes were considered.

Results

Nineteen articles (representing 15 individual studies) were included for review. Heterogeneity in interventions and outcomes across studies meant meta-analyses were not possible. Participants were all patients with bladder cancer and interventions were delivered over different stages of the perioperative period. The overall quality of evidence and reporting was low and outcomes were predominantly measured in the short-term. However, the findings show potential for exercise therapy, pharmaceuticals, ERAS protocols, psychological/educational programmes, chewing gum and nutrition to benefit a broad range of physiological and psychological health outcomes.

Conclusions

Supportive interventions to date have taken many different forms with a range of potentially meaningful physiological and psychological health outcomes for cystectomy patients. Questions remain as to what magnitude of short-term health improvements would lead to clinically relevant changes in the overall patient experience of surgery and long-term recovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Perioperative complications from cystectomy and urinary diversion can be short- and long-term, physiological and psychological [1]. Postoperative morbidity and complication rates can lead to long hospital stays [2] and high readmission rates [3]. Surviving patients can experience emotional, physical and social challenges and changes in quality of life (QOL) [1]. The range of perioperative complications associated with cystectomy procedures requires a multidisciplinary approach to preoperative supportive care and postoperative rehabilitation [4].

Perioperative interventions should support patients’ psychological health as much as physical health [5]. The optimal perioperative supportive interventions for cystectomy patients and associated health outcomes are currently uncertain. Evidence-based interventions have traditionally been non-standardised but have evolved into clinical pathways of care known as enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols. ERAS protocols involve a series of perioperative care modifications and supportive interventions with the aim to achieve early recovery by maintaining preoperative organ function and reducing physiological stress response following surgery [6]. ERAS protocols after cystectomy have had a low adoption [7], yet have been found to shorten hospital stay [3] without an increase postoperative morbidity [8]. Our understanding of the active ingredients of such protocols and how these may affect the overall patient experience in the long-term is limited and previous comprehensive reviews have involved non-randomised observational studies only [9] . Further exploration of the available evidence using rigorous systematic review methodology is required to develop our understanding of how to promote clinically relevant health outcomes for cystectomy patients.

The aim of this review is to summarise the available evidence base for any supportive interventions designed to improve short and/or long-term physiological and psychological health outcomes among patients undergoing cystectomy. Reviewing the literature of the wide range of perioperative supportive interventions and their related health outcomes will advance our understanding of what works for patients undergoing cystectomy.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature was performed in January 2018. Records were identified from MEDLINE, AMED, PsycInfo and EMBASE databases and the Cochrane collaboration. The search was limited to studies involving adult humans and published in the English language and not limited by date of publication. Literature search terms are available as supplementary material (see Additional file 1). Further searches were made for unpublished and grey literature. The http://www.clinicaltrials.gov website was searched for ongoing trials. The citation lists of included studies and previous systematic reviews were also checked to identify relevant studies.

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving any non-surgical, perioperative interventions designed to support or improve the patient experience, including lifestyle, physical, medical and psychological treatments were considered for review. The intention was not to assess the effects of different forms of surgical diversion. Studies were eligible if they involved adults ≥18 years who were due to undergo or had undergone a cystectomy procedure and any method of urinary diversion. Supportive interventions could be implemented during diagnosis and treatment planning, the perioperative period, and during the length of hospital stay, follow-up and postoperative period. Interventions could be hospital-based or home-based. Comparison groups included those exposed to usual clinical care or standard procedure. Studies were excluded if they did not involve an intervention, or the intervention involved a surgical procedure only, bowel preparation only or an alternative therapy such as aromatherapy. Any outcomes reflecting the patient experience or related urological health outcomes were considered and could be physiological, psychological, behavioural and social.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

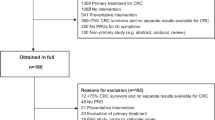

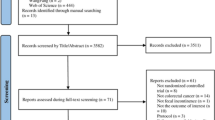

Following de-duplication, titles and abstracts of identified records were screened by one reviewer (HQ) and 10% were selected at random and checked independently by a second reviewer (LB). The full texts of potentially eligible records were retrieved and screened independently by the two reviewers (HQ, LB). Multiple records of the same study were linked together in the process. The study selection process is described in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Data extraction and management

The full text of each article was read by two reviewers independently (HQ, LB) and after piloting of extraction tables, relevant data were extracted. Any discrepancies in data extraction between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion. The authors of included studies were contacted via email for clarification of unclear study methods or data wherever insufficient details were reported.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias of each included study was assessed by two reviewers (HQ, LB) working independently using the recommended tool in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention [10]. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Dealing with missing data

Missing data and dropout rates for each of the included studies were assessed. When possible, all data extracted were relevant to an intention-to-treat analysis, in which participants were analysed in the groups to which they were assigned.

Assessment of heterogeneity and sensitivity analyses

Statistical methods for assessing heterogeneity and sensitivity analyses were planned, depending on the availability of data.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Meta-analyses were planned for wherever there was more than one RCT reporting the same outcome. Where meta-analyses were not feasible, a narrative synthesis approach was used [11].

Results

The search identified 63 articles meeting the inclusion criteria for full text screening (Fig. 1). In all, 44 articles were excluded and the reasons recorded. The remaining 19 articles (representing 15 individual studies) were included in the review. Studies were published between 1989 [12] and 2017 [13,14,15] and were conducted in ten different countries; one was UK-based [14] (see Table 1).

Participants

Table 1 provides a summary of participant characteristics. All studies involved patients with bladder cancer undergoing radical cystectomy. Sample sizes ranged from 8 [15] to 280 [16], with a total of 1145 participants across all studies. The average age of participants ranged from 45.3 years (mean) [12] to 74.5 years (median) [15]. Most studies included both sexes, except two studies that included males only [15, 17]. Other patient characteristics, though not reported consistently included BMI, ethnicity, comorbidities, smoking history, and socio-economic data.

Interventions

See Table 2 for a summary of interventions included in this review.

Type

Intervention types included; exercise therapy [14, 18,19,20,21], pharmaceutical [16, 22, 23], ERAS protocol [17, 24, 25], psychological/educational [1, 12, 13, 15], chewing gum [26], and nutritional [27,28,29]. Interventions were delivered by exercise science staff [14], physiotherapists [18,19,20,21], Urological Enteral Stoma Therapy Nurses [13], trained nurse practitioners [15], hospital ward staff [27], and staff nurses [23], healthcare professionals [17] and study investigator [26]. Seven did not report who delivered the intervention [1, 12, 16, 22, 24, 25, 28]. Treatments to control group patients were determined by the standard procedure at the local hospital which may have involved some ERAS items [18,19,20, 25] and were not consistent across studies.

Recruitment and intervention setting

The majority of studies recruited participants via a single hospital urology department, two studies recruited across multiple centres [16, 28] and three did not report recruitment setting [1, 22, 24]. Intervention settings were hospital based [12, 15,16,17, 22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29], hospital and home based [13, 18,19,20,21], home-based [1] or supervised exercise setting [14].

Time, duration and frequency

Studies varied in time of intervention delivery; preoperative, postoperative or perioperative (see Table 2). Duration of intervention varied from 30 to 60 min for a single educational intervention [12, 15] to 12 weeks for the physical exercise intervention [21]. Six studies did not have standardised intervention duration; Banerjee et al.’s [14] exercise intervention took place preoperatively until surgery, Choi et al.’s [26] chewing gum intervention continued until first flatus, Deibert et al.’s [28] dietary intervention was postoperative until discharge, and those studies implementing ERAS protocols took place over the perioperative period until discharge [17, 24, 25]. Frequency of intervention administration differed depending on the intervention type (see Table 2).

Measurements

Methods of measuring outcomes varied across studies, making direct comparisons between studies difficult. Hospital records were used to measure length of stay (LOS) and readmission rate. Hospital measurements were used to assess functions such as bowel function and flatus, food tolerance and mobilisation. Complications were assessed using the standardised Clavien-Dindo classification system [14, 17, 20, 25,26,27,28] or via hospital reports. Symptoms (e.g., pain, fatigue, vomiting) tended to be self-reported using patient questionnaires. Three studies [18, 24, 25] used the validated European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) [30] to assess quality of life (QOL) and in-patient satisfaction. Three studies used a visual analogue scale (VAS) to measure pain intensity [22, 23, 28], one study used Sickness Impact Profile (SIP) to measure sickness-related dysfunction and postoperative adjustment [1], two studies used the Short Form health survey (SF-36 and SF-12) to evaluate health-related QOL [21, 29], one used the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy- Bladder Cancer (FACT-BL) questionnaire to measure QOL [25] and one used the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) to measure state anxiety [12]. Self-care was measured using the Urostomy Education Scale (UES) [13]. Self-efficacy was measured using the six-item Self-Efficacy to Manage Chronic Disease (SES6G) scale [15].

Outcome measurement (length of follow-up) tended to be short term (up to 30 days postoperatively) in the majority of articles reviewed (n = 11), and ranged between 24 h postoperatively [23] to a median of 50 months after surgery (IQR 21–62 months) [29] (See Table 2).

Effect of interventions

The outcomes used to measure the effect of interventions are summarised in Table 3. Differences in definitions and measurements of outcomes across studies meant that meta-analyses were not possible.

Length of stay and readmission

Length of stay (LOS) was reported in 11 articles [1, 14, 16, 17, 20, 21, 24,25,26,27,28]. The most common definition of LOS was total hospital stay duration in days. Two studies defined it as postoperative days (from surgery until discharge) [1, 16]. Median LOS ranged from 7 [14] to 21 days [1]. Frees et al. [25] and Lee et al. [16] found a significant difference in LOS between intervention and control groups. Frees et al. found LOS was significantly shorter in the patients receiving ERAS protocol compared to standard procedure (mean 6.1 days vs. 7.39 days; p = 0.020). Lee et al. found mean LOS was significantly shorter in patients given alvimopan compared to placebo controls (alvimopan, 7.44 days; control 10.07 days; p < 0.01).

Frequency of readmission to hospital after discharge was measured as an outcome in five studies [16, 20, 21, 25, 28]. No study reported significant results for readmission rates after supportive intervention compared to controls.

Physiological adjustment after surgery

Bowel function and flatus

Nine studies measured bowel function [18, 20, 27, 28], also defined as time to first defecation or bowel movement [17, 25, 26], constipation [24] and lower gastrointestinal function [16]. Statistically significant reductions in average time until first bowel movement were found in four studies after the intervention; ERAS protocol [25], chewing gum [26], physical exercise [18] and alvimopan [16]. Time to first flatus was measured in five studies [17, 18, 25,26,27] and three found statistically significant reductions in time after ERAS protocol [25], chewing gum [26] and physical exercise [18]. Frees et al. [25] found significant reduction in time to first flatulence in the ERAS group compared to the standard procedure controls (2.5 days compared to 3.62 days) (p = 0.011).

Food tolerance

Six studies measured food tolerance, defined at nutritional intake [20], appetite loss [24], gastrointestinal recovery/tolerance of solid food [16], early feeding [17] and resumption of full diet [27]. Deibert et al. [28] found time to full diet tolerance was the same in both early diet and control arms, respectively (5.84 days vs 6.71 days, p = 0.27). Lee et al. [16] found mean time to gastrointestinal recovery was 1.3 days shorter for the alvimopan group (5.5 days) compared with the placebo control group (6.8 days; 95% CI, 1.4 to 2.3; p < 0.0001). Karl et al. [24] found that the amount of food consumed in relation to the amount of food offered on postoperative day 3 was significantly higher in the ERAS group compared to standard procedure controls (p = 0.02).

Nausea and vomiting

Four studies measured vomiting [22], nausea [25] or both [18, 24] and none reported any significant differences between intervention and control groups after the intervention.

Pain

Six studies measured pain [18, 21,22,23,24,25]. Three studies reported statistically significant pain outcomes. Ghoneim and Hegazy [22] found VAS score to be significantly lower postoperatively until 32 h in the intervention group receiving preoperative pregabalin compared to the control group (p < 0.05), but found no significant difference 32–48 h postoperatively. Mohamed et al. [23] found a significant reduction in VAS score in intervention groups who received preoperative pregabalin in comparison with the control group immediately after surgery, and 2 h postoperatively (p < 0.05). Frees et al. [25] found ERAS patients reported a reduction in VAS score every day after surgery until day 7 compared to patients undergoing standard procedure. This difference reached statistical significance on the day of surgery (p = 0.017) and from postoperative days 2 (p = 0.014) to 4 (p = 0.039), where pain intensity was nearly doubled for patients who received standard procedure.

Fatigue

Two studies measured fatigue using the EORTC symptom scale [18, 24]. Jensen et al. [18] found the control group (no physical exercise intervention) demonstrated a clinically relevant reduction in fatigue symptoms at 4 months follow-up that was not statistically significant. Karl et al. [24] reported significant differences in fatigue scores between the ERAS and control group at day 7 (p = 0.014) and discharge (p = 0.003), but did not report the group data.

Mobilisation, strength/power and balance

Three studies measured mobilisation [20, 21, 24], defined as the distance walked during the first seven postoperative days [20], mobilisation and walking distance [24] and distance walked in the 6 min walk test [21]. Jensen et al. [20] reported significantly longer average walking distance in the intervention group after the physical exercise intervention (4806 m walked; 95% CI, 4075 to 5536 m), compared to the control group (2906 m walked; 95% CI, 2408 to 3404 m; p < 0.001). Karl et al. [24] reported that patients in the ERAS group covered significantly greater walking distances by postoperative day 3 compared to controls (p = 0.039). Porserud et al. [20, 21] found that after the 12 week exercise training period, both the intervention and the control group patients had increased the distance walked (p = 0.043 and p = 0.012, respectively), but the increase was higher among the intervention group (p = 0.013) who had exercised postoperatively. One year later, the exercise group continued to have increased walking distance compared to controls (p = 0.010).

The three studies using exercise therapy measured strength or power. Jensen et al. [19] measured strength as muscle leg power (W/kg) using a leg extensor power test and found that the prehabilitation physical exercise programme led to a significant improvement in muscle power in the intervention group of 0.35 W/kg (95% CI, 0.12 to 0.54) at time for surgery compared to baseline (p < 0.002) with a significant difference between intervention and control group. Banerjee et al. [14] implemented a short-term preoperative vigorous intensity aerobic interval exercise programme on a cycle ergometer and showed that after 3–6 weeks of training, statistically significant differences in peak power output (W) were found between the exercise group (148 ± 41; 95% CI, 132 to 165) compared to non-exercising controls (129 ± 44; 95% CI, 111 to 147; p < 0.001) [14]. Porserud et al. [21] measured lower body strength using a 30-s chair stand test and found no significant differences between the intervention and control group. Porserud et al. also measured balance by asking patients to walk two laps in a figure of eight drawn on the floor, with a walking aid if necessary and found no significant differences between intervention and control group post-intervention or 1 year later [20].

Physical function

Three studies measured physical function, two using the EORTC-QLQ-30 [18, 24] and one using the SF-36 [21]. No statistical differences were found, except for Karl et al.’s [24] study, which found statistically higher physical functioning scores on postoperative day 3 for patients in the ERAS group.

Dyspnoea

Dyspnoea was measured in two studies using the EORTC-QLQ-30 [18, 24]. Jensen et al. [18] found a 10% significant decrease in symptoms of dyspnoea in the intervention group (physical exercise rehabilitation) compared with the control group at 4 month follow-up. Karl et al. [24] reported no significant differences between intervention and control group after the ERAS protocol.

Insomnia

Insomnia was measured in two studies using the EORTC-QLQ-30 [18, 24] and no significant differences between intervention and control groups were found after the intervention.

Sexual function

Two studies measured sexual function [18, 29]. Jensen et al. [18] found an improvement of 7% in sexual interest and activity in the control group 4 months after the intervention, which they described as clinically relevant though it was not statistically significant. Vidal et al. [29] measured sexual function as a long-term follow-up to the TPN nutritional intervention described by Roth et al. [27] and found no statistically significant differences between intervention and control group at 0, 3, 12 and 24 month follow-ups.

Psychological adjustment after surgery

Social and emotional functioning

Four studies measured social and emotional functioning using EORTC-QLQ-30 [18, 24], the SF-36 [21] and the SIP questionnaire [1]. No study found statistically significant differences between intervention and control groups after the intervention except Karl et al. [24] who found a stable emotional functioning score during hospitalisation in the control group and continuous improvement in emotional functioning until discharge in patients exposed to the ERAS protocol (no data reported) [24].

Health related quality of life

Five studies measured QOL, one using the FACT-BL [25], two using global health-related QOL from the EORTC-QLQ-30 and functional subscales [18, 24] and two using the SF-12 or 36 [21, 29]. Porserud et al. [21] found no statistically significant differences between intervention and control group in the QOL domains. Jensen et al. [18] found the physical rehabilitation intervention group demonstrated a clinically relevant decrease compared to the control group on role function and cognitive function at the 4 month follow-up, although differences were not statistically significant. Frees et al. [25] and Vidal et al. [29] found no statistically significant differences between intervention and control groups in QOL scores.

Self-care and self-efficacy

Three studies measured self-care [13, 15, 20] and two measured self-efficacy [13, 15] as outcomes of the intervention. Jensen et al. [20] found the ability to independently perform personal activities of daily living was significantly reduced by 1 day in the intervention group after pre-and postoperative physical exercise intervention compared to controls (3 days vs 4 days; p ≤ 0.05). Jensen et al. [13] found no statistical significant difference (p = 0.35) in mean self-efficacy score between treatment groups on admission to surgery. However, a significant increase in the total stoma self-care score of 2.7 points (95% CI, 0.9 to 4.5) was found in the intervention group compared to the standard procedure group at postoperative day 35, and differences continued at day 120 (4.3 95% CI, 2.1 to 6.5) and 365 (5.1 95% CI, 2.3 to 7.8). Merandy et al. [15] found that the single preoperative educational intervention was not associated with self-care independence scores (p = 0.4286) and brought about no significant change in self-care or self-efficacy scores.

Other outcomes

Other outcome measures explored in isolation included vitality and mental health [21] and anxiety [12]. Porserud et al. [21] found no significant differences between intervention and control group in vitality and mental health scores as measured by the SF-36. Ali and Khalil [12] found patients who received psychoeducational preparation prior to surgery showed less state anxiety on the third day postoperatively than the control group (p < 0.00 [sic]) and before discharge (p < 0.00 [sic]) compared to controls. Through a qualitative analysis, Ali and Khalil [12] also found that patients fears and worries before surgery concerned i) cancer, ii) mutilation and body image distortion, and iii) impact on social/marital relationships.

Complications

Eleven studies reported complications associated with the surgical procedures, seven using the standardised Clavien-Dindo classification system [14, 17, 20, 25,26,27,28] (See Additional file 2). Generally, interventions were not found to substantially increase the normal complication rate, with the exception of one study that was terminated prematurely due to high gastrointestinal complications in patients exposed to total parenteral nutrition (TPN) for 5 days postoperatively [27].

Adherence and fidelity

Adherence to the intervention was reported in eight articles. Table 4 gives a summary of the adherence reported in each of the articles under review. Eleven articles did not report adherence to the intervention. Fidelity of the intervention delivery was not reported in any article.

Risk of bias

Figure 2 shows the risk of bias summary table for the studies included. The standard of reporting was generally low, with many articles omitting Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) details [31]. Low reporting quality meant the majority of studies were judged to have unclear risk of bias on at least one domain. All studies were described as having randomised designs, but only ten articles reported the randomisation procedure (e.g., web-based block randomisation [18]). In eight articles, it was unclear how participants were randomised. One study was described as randomised but did not describe a true randomisation procedure, therefore considered high risk of bias [15]. Seven studies were rated low risk for ‘selection bias’, because they referred to allocation concealment in their reporting of the randomisation procedure [13, 18,19,20,21, 23]. Studies tended to be rated as unclear or high risk for ‘performance bias’ and ‘detection bias’ because it was unclear whether patients, study personnel or outcome assessors were blind to the treatment group. Double-blind RCTs are difficult, if not impossible for many non-pharmaceutical intervention studies, exposing most of the studies to performance bias. Two studies included in the review were described as double-blind [16, 23]. All studies were judged to be at high risk of some ‘other bias’. This included, use of a single centre [12], different surgical and treatment procedures across different sites [16], LOS being influenced by hospital discharge rules (rather than health outcomes) [26], small sample sizes [1, 12, 17, 21, 22, 26], change over time in surgical procedure [18,19,20], intervention and control group patients being treated on the same hospital ward [18,19,20], use of male patients only [17], not recruiting the target sample size [21, 28] and premature termination of the study [27, 29].

Heterogeneity and sensitivity analyses

Differences in the included studies, particularly in types of interventions, definitions of outcomes and tools used to measure outcomes meant sensitivity analyses could not be conducted and heterogeneity could not be assessed statistically.

Discussion

Supportive interventions for cystectomy patients have included exercise therapy, pharmaceuticals, ERAS protocols, psychological/educational programmes, chewing gum and nutrition delivered at various stages over the perioperative period. It is difficult to make clear recommendations for clinical practice, especially for potential long-term benefits to patient health, but this review can offer suggestions for potential short-term benefits of interventions.

Review findings suggest that integrating exercise therapy into the pre- or postoperative care of cystectomy patients could have clinically important benefits for bowel function, physical function, strength/power, mobilisation and QOL but is not always feasible for patients. The findings align with other reviews demonstrating the positive effects of exercise for bladder cancer patients [32]. Exercise can be challenging for cancer patients and requires careful consideration with respect to patient age and comorbidities [18, 33]. Research exploring the optimal type of exercise therapy would be informative, as intensive exercise may not always be appropriate [21] or accessible [14] for patients undergoing cystectomy.

Cystectomy patients may benefit from pharmaceutical intervention for pain relief and physical function in the immediate postoperative period, which is likely to have a positive impact on length of hospital stay, QOL, the patient experience and healthcare costs. However, the effect on pain management might be short-lived and side-effects such as the sedative effect of pregabalin should be considered [22, 23].

Only three of the included studies used ERAS protocols [17, 24, 25], supporting the observation that the adoption of ERAS protocols in urological procedures to date has been low [6]. The findings suggest that ERAS protocols have the potential to offer widest range of benefits for cystectomy patients. However, it is hard to identify what actually works within each context and the quality and quantity of the evidence needs improvement. Tyson and Chang [9] systematically reviewed 13 studies comparing ERAS after cystectomy versus standard care with a meta-analysis of effectiveness. ERAS protocols were investigated within observational studies only and were found to reduce the LOS, time-to-bowel function, and rate of complications after cystectomy, but the pooled estimates were biased in favour of ERAS and each perioperative pathway was different within each study [9]. If ERAS protocols are to be adopted, then high-quality multicentre studies are needed to accumulate evidence supporting the short and long-term impact of their use.

The findings demonstrate that psychologically-supportive and educational interventions are less common than physical or medical interventions, but could reduce postoperative anxiety and promote postoperative adjustment, self-care and coping in cystectomy patients. Such outcomes are likely to benefit QOL and positive adjustments with clinical relevance [13], but are likely to require a longer and more individualised approach than those implemented in the studies included in this review. The findings are consistent with a previous systematic review of exercise and psychosocial rehabilitation interventions to improve health-related outcomes in patients with bladder cancer undergoing radical cystectomy, which found limited evidence for beneficial effects of psychosocial interventions [32]. Given that poor preoperative mental health has been associated with complications after cystectomy [34] and postoperative problems can have a significant impact on QOL [5], assessing perioperative psychological health status could help identify those patients who may be in need of extra support. Further research is required to explore the best approach to provision of psychological support for patients to ensure that patients are not only surviving, but surviving well.

Asking cystectomy patients to chew gum postoperatively may have benefits for bowel function and is unlikely to have any adverse effects. The early introduction of diet was feasible and safe, but TPN was associated with an increased rate of infectious complications, impaired bowel function, as well as higher costs [27].

Some level of bias was present in all studies included in this review, with most of the uncertainty in judging bias coming from lack of clarity of randomisation and blinding procedures. Methodological details were underreported and future publications should adequately report high quality research. No study reported fidelity of intervention delivery meaning it was unclear whether the treatment was delivered as intended. Additionally, the surgical procedure, including form of urinary diversion to control group patients varied across studies (see Table 1), introducing potentially confounding factors. This makes it difficult to show whether any health benefits were related to the supportive intervention or to determine the optimal ‘dosage’ or exposure to the intervention required to bring about health benefits. Many of the studies lacked statistical power due to small sample sizes meaning statistical significance should be interpreted with caution.

Recommendations for future research

Implications for clinical practice have been difficult to make, suggesting that future research should explore the clinical relevance of the outcomes found in research studies. Maintenance data through longer follow-ups are essential to explore i) long-term complications and readmissions and ii) whether short-term health outcomes are sustained over time. Adequately powered clinical trials are required to explore the long-term effects of physical prehabilitation and rehabilitation for cystectomy survivors. More research exploring psychologically-supportive interventions would be informative because the current findings highlight that psychological and behavioural outcomes (e.g., self-care behaviour and behaviour change) are scarcely studied and poorly understood. Standards of reporting must be improved, including details of fidelity and adherence.

Conclusions

This review provides a broad overview of the non-surgical supportive interventions available to help optimise the health outcomes of patients undergoing cystectomy procedures. It has shown that supportive interventions have taken many different forms with a range of potentially meaningful physiological and psychological health outcomes for patients in the short and long term after surgery. Questions remain as to what magnitude of improvements in the physiological and psychological health outcomes reported would lead to actual changes in the patient experience of surgery and recovery. Whilst this review can offer suggestions for potential benefits of interventions, clarification is required to understand what forms of support are most effective in improving the long-term quality of life of cystectomy patients.

Abbreviations

- CONSORT:

-

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- EORTC-QLQ-30:

-

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer - Quality of life of cancer patients

- ERAS:

-

Enhanced recovery after survey

- FACT-BL:

-

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy- Bladder Cancer

- LOS:

-

Length of stay

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial

- SES6G:

-

Self-Efficacy to Manage Chronic Disease scale

- SF-36 and SF-12:

-

Short Form health survey

- SIP:

-

Sickness Impact Profile

- STAI:

-

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

- UES:

-

Urostomy Education Scale

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

References

Månsson Å, Colleen S, Hermeren G, Johnson G. Which patients will benefit from psychosocial intervention after cystectomy for bladder cancer? Br J Urol. 1997;80(1):50–7.

Baumgartner RG, Wells N, Chang SS, Cookson MS, Smith JA Jr. Causes of increased length of stay following radical cystectomy. Urol Nurs. 2002;22(5):319.

Altobelli E, Buscarini M, Gill HS, Skinner EC. Readmission Rate and Causes at 90-Day after Radical Cystectomy in Patients on Early Recovery after Surgery Protocol. Bladder Cancer. 2017;3(1):51–6.

Kehlet H. Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78(5):606–17.

Palapattu GS, Haisfield-Wolfe ME, Walker JM, Brintzenhofeszoc K, Trock B, Zabora J, Schoenberg M. Assessment of perioperative psychological distress in patients undergoing radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. J Urol. 2004;172(5):1814–7.

Azhar RA, Bochner B, Catto J, Goh AC, Kelly J, Patel HD, Pruthi RS, Thalmann GN, Desai M. Enhanced recovery after urological surgery: a contemporary systematic review of outcomes, key elements, and research needs. Eur Urol. 2016;70(1):176–87.

Cerantola Y, Valerio M, Persson B, Jichlinski P, Ljungqvist O, Hubner M, Kassouf W, Muller S, Baldini G, Carli F. Guidelines for perioperative care after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) society recommendations. Clin Nutr. 2013;32(6):879–87.

Daneshmand S, Ahmadi H, Schuckman AK, Mitra AP, Cai J, Miranda G, Djaladat H. Enhanced recovery protocol after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. J Urol. 2014;192(1):50–6.

Tyson MD, Chang SS. Enhanced Recovery Pathways Versus Standard Care After Cystectomy: A Meta-analysis of the Effect on Perioperative Outcomes. Eur Urol. 2016;70(6):995–1003.

Higgins J, Green S: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions In., vol. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011: Available from http://handbook.cochrane.org.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, Britten N: Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: A product from the ESRC Methods Programme. In., vol. Version 1. Lancaster University, Lancaster; 2006: b92.

Ali NS, Khalil HZ. Effect of psychoeducational intervention on anxiety among Egyptian bladder cancer patients. Cancer Nurs. 1989;12(4):236–42.

Jensen B, Sondergaard I, Kiesbye B, Jensen J, Kristensen S. Efficacy of preoperative uro-stoma-education on self-efficacy after radical cystectomy; Secondary outcome from a prospective randomized controlled trial. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2017;28:41–6.

Banerjee S, Manley K, Shaw B, Lewis L, Cucato G, Mills R, Rochester M, Clark A, Saxton JM. Vigorous intensity aerobic interval exercise in bladder cancer patients prior to radical cystectomy: a feasibility randomised controlled trial. Support Care Cancer. 2017;26(5):1515–23.

Merandy K, Morgan MA, Lee R, Scherr DS. Improving self-efficacy and self-care in adult patients with a urinary diversion: A pilot study. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2017;44(3):e90–e100.

Lee CT, Chang SS, Kamat AM, Amiel G, Beard TL, Fergany A, Karnes RJ, Kurz A, Menon V, Sexton WJ, et al. Alvimopan accelerates gastrointestinal recovery after radical cystectomy: a multicenter randomized placebo-controlled trial. Eur Urol. 2014;66(2):265–72.

Olaru V, Gingu C, Baston C, Manea I, Domnisor L, Preda A, Voinea S, Stefan B, Dudu C, Sinescu I. Applying fast-track protocols in bladder cancer patients undergoing radical cystectomy with ileal urinary diversions-early results of a prospective randomized controlled single center study. Rom J Urol. 2015;14(4):58.

Jensen BT, Jensen JB, Laustsen S, Petersen AK, Søndergaard I, Borre M. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation can impact on health-related quality of life outcome in radical cystectomy: secondary reported outcome of a randomized controlled trial. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2014;7:301.

Jensen B, Laustsen S, Jensen J, Borre M, Petersen A. Exercise-based prehabilitation is feasible and effective in radical cystectomy pathways-secondary results from a randomized controlled trial. J Urol. 2016;195:e652.

Jensen B, Petersen A, Jensen J, Laustsen S, Borre M. Efficacy of a multiprofessional rehabilitation programme in radical cystectomy pathways: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Scand J Urol. 2015;49:133–41.

Porserud A, Sherif A, Tollbäck A. The effects of a physical exercise programme after radical cystectomy for urinary bladder cancer. A pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2014;28(5):451–9.

Ghoneim AA, Hegazy MM. The analgesic effect of preoperative pregabalin in radical cystectomy for cancer bladder patients. Chinese-German J Clin Oncol. 2013;12(3):113–7.

Mohamed MA, Othman AH, Abd El-Rahman AM. Analgesic efficacy and safety of peri-operative pregabalin following radical cystectomy: A dose grading study. Egypt J Anaesth. 2016;32(4):513–7.

Karl A, Buchner A, Becker A, Staehler M, Seitz M, Khoder W, Schneevoigt B, Weninger E, Rittler P, Grimm T. A new concept for early recovery after surgery for patients undergoing radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: results of a prospective randomized study. J Urol. 2014;191(2):335–40.

Frees S, Aning J, Black P, Struss W, Bell R, Gleave M, So A. A prospective randomized single-centre trial evaluating an ERAS protocol versus a standard protocol for patients treated with radical cystectomy and urinary diversion for bladder cancer. Eur Urol Suppl. 2017;16(3):e1024.

Choi H, Kang SH, Yoon DK, Kang SG, Ko HY, Moon DG, Park JY, Joo KJ, Cheon J. Chewing gum has a stimulatory effect on bowel motility in patients after open or robotic radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: a prospective randomized comparative study. Urology. 2011;77(4):884–90.

Roth B, Birkhäuser FD, Zehnder P, Thalmann GN, Huwyler M, Burkhard FC, Studer UE. Parenteral nutrition does not improve postoperative recovery from radical cystectomy: results of a prospective randomised trial. Eur Urol. 2013;63(3):475–82.

Deibert CM, Silva MV, RoyChoudhury A, McKiernan JM, Scherr DS, Seres D, Benson MC. A Prospective Randomized Trial of the Effects of Early Enteral Feeding After Radical Cystectomy. Urology. 2016;96:69–73.

Vidal Faune A, Arnold N, Vartolomei M, Kiss B, Burkhard FC, Thalmann GN, Roth B. Does postoperative parenteral nutrition after radical cystectomy impact oncological and functional outcomes in bladder cancer patients? European Urology. Supplements. 2016;15(3):e515.

Sprangers M, Cull A, Groenvold M, Bjordal K, Blazeby J, Aaronson NK. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer approach to developing questionnaire modules: an update and overview. Qual Life Res. 1998;7(4):291–300.

Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, Horton R, Moher D, Olkin I, Pitkin R, Rennie D, Schulz KF, Simel D. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials: the CONSORT statement. Jama. 1996;276(8):637–9.

Rammant E, Decaestecker K, Bultijnck R, Sundahl N, Ost P, Pauwels NS, Deforche B, Pieters R, Fonteyne V. A systematic review of exercise and psychosocial rehabilitation interventions to improve health-related outcomes in patients with bladder cancer undergoing radical cystectomy. Clin rehabil. 2017;32(5):594–606.

Bourke L, Smith D, Steed L, Hooper R, Carter A, Catto J, Albertsen PC, Tombal B, Payne HA, Rosario DJ. Exercise for men with prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2016;69(4):693–703.

Sharma P, Henriksen CH, Zargar-Shoshtari K, Xin R, Poch MA, Pow-Sang JM, Sexton WJ, Spiess PE, Gilbert SM. Preoperative patient reported mental health is associated with high grade complications after radical cystectomy. J Urol. 2016;195(1):47–52.

Funding

The review was funded by the Urostomy Association. The Urostomy Association commissioned researchers to conduct the review and had no role in the design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data or writing of this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LB obtained funding and made substantial contributions to the conception of the review. HQ and LB contributed to the literature search, screening, data extraction and analysis of the data. DR and LB made substantial contributions to the interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. HQ drafted the manuscript and all authors have read, contributed to and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Search terms - Literature search terms for the electronic database search used in this review. (DOCX 22 kb)

Additional file 2:

Summary of complications - Summary of reported complications for each study included in this review. (DOCX 30 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Quirk, H., Rosario, D.J. & Bourke, L. Supportive interventions to improve physiological and psychological health outcomes among patients undergoing cystectomy: a systematic review. BMC Urol 18, 71 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-018-0382-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-018-0382-z