Abstract

Background

Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) is an important cause of acute respiratory failure (ARF) in immunocompromised patients, yet no actual clinical tool suitably identifies patients at risk. Recently, a multivariable prediction model has been proposed for haematology patients with ARF requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission to assess the risk of PCP (PCP score). However, it has not yet been validated externally.

Methods

To validate the PCP score, a retrospective cohort study was conducted in two large designated haematology centres in Korea. One-hundred and forty haematology patients with ARF were admitted to ICU. They underwent aetiologic evaluations between July 2016 and June 2019. The predictive ability of the score was assessed with the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis for both the discrimination and calibration of the score.

Results

Among the 141 patients, 13 (9.2%) were finally diagnosed of PCP. Although the median of PCP score in PCP group was higher than in non-PCP group (3.0 [interquartile range 0.0–4.0] vs. 2.0 [0.5–4.0]), the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.679). The area under the ROC curve of the PCP score in our cohort was 0.535 (95% CI, 0.449–0.620), indicating no discriminatory ability. When using a cut-off of 3.0 the score, the result was 38.5% (95% CI, 13.9–68.4) sensitive and 7.03% (95% CI, 61.6–78.1) specific. The negative predictive value was 58.8% and positive predictive value was 59.8% for a 10% prevalence of PCP.

Conclusions

In this study, the PCP score was not useful to predict the risk of PCP in haematology patients with ARF. Further prospective validation studies are needed to validate the score’s use in routine clinical practice for the early diagnosis of PCP in haematology patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

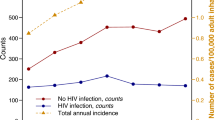

Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP), a pulmonary infection caused by Pneumocystis jirovecii, is an important cause of acute respiratory failure (ARF) in immunocompromised patients [1,2,3,4,5]. PCP is most commonly associated with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. However, the development of highly active antiretroviral therapy and effective prophylaxis against PCP have reduced its prevalence and the mortality rate in HIV-positive patients [6, 7]. Consequently, more attention is placed on other immunocompromised states [8,9,10].

Haematologic malignancies are the most common underlying conditions associated with the development of PCP in HIV-negative patients [11, 12]. Compared to HIV-positive patients who follow a more indolent course [13, 14], haematology patients with PCP present with abrupt-onset hypoxemic respiratory failure, and more often require mechanical ventilation [13,14,15]. In addition, delays in anti-PCP treatment are associated with poor outcomes [13, 16]. However, inappropriate use of TMP/SMX should be avoided not only prevent drug related side effects including granulocytopenia, hepatotoxicity, and nephrotoxicity, but also prevent delay of inaccurate diagnosis or resistant strains. Nonetheless, the confirmative diagnosis of PCP with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) would be challenging in haematology patients with hypoxemic respiratory failure, making it difficult to perform bronchoscopy [10, 14]. Therefore, a clinical tool that rapidly identifies patients at risk of PCP (in whom empiric treatment is warranted), should be developed and consequently avoiding delays in anti-PCP treatment [17].

Recently, Azoulay et al. introduced a multivariable prediction model to assess the risk of PCP (PCP score) for haematology patients with ARF requiring ICU admission and they reported a good performance of the PCP score [18]. However, there have been no external validations of the prediction model with other cohorts. In this study, we then assessed the performance of the PCP score in haematology patients from two large designated haematology centres in Korea.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of all consecutive haematology patients admitted in the medical intensive care unit (ICU) for respiratory failure at Samsung Medical Center (a 1989-bed, university-affiliated, tertiary referral hospital in Seoul, South Korea) and Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital (a 1369-bed, university-affiliated, tertiary referral hospital in Seoul, South Korea) between July 2016 and June 2019. The Institutional Review Boards of each participating hospital with patient records approved the present study and the informed consent was waived because of the non-interventional nature of this research. All patient records and data were anonymised and coded prior to analysis.

Study population

All consecutive haematology patients older than 20 years who were admitted to the medical ICU for ARF were screened for inclusion. Patients were included if they received BAL with or without a transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB) for aetiologic explorations, and a results of microbiological identification of Pneumocystis jirovecii in BAL fluid or lung tissue were included (Fig. 1). Patients were excluded if they had a positive HIV antibody test. For cases with multiple admissions for ARF during the study period, only the first ICU admission was evaluated.

Pneumocystis pneumonia score

Azoulay et al. developed a PCP score for haematology patients with ARF using a cohort with PCP prevalence of 11.2% (149 of 1330), in which PCP was confirmed by identification of P. jirovecii cysts or trophozoites in BAL fluid or induced sputum [18]. The PCP score uses parameters: age, lymphoproliferative disease, anti-PCP prophylaxis, day between respiratory symptom onset and ICU admission, shock at ICU admission, and chest X-ray results (showing pleural effusion or not, gotten at ICU admission). The PCP score ranged from - 6 to 8.5, and higher scores indicated more possibility of PCP and the cut-off value of the PCP score was found to be 3.0 from the validation cohort.

Data collection

Data extracted from the medical records include general demographic information, underlying haematologic disease and medications received during the previous month. Furthermore, PCP prophylaxis, initial presentation of symptoms, vital signs/organ supports at ICU admission and chest radiographic findings. We also collected laboratory data such the white blood cell count, albumin, C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, lactate dehydrogenase, and haemoglobin. Severity of illness was assessed using the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score [19]. The data included integral components of the PCP score [18].

The diagnosis of PCP was based on the identification of the organism in BAL fluid or lung tissue obtained by TBLB. BAL fluid samples were stained using Gram and Ziehl-Neelsen methods and then cultured for bacteria, mycobacteria and fungi. Microbiological identification of P. jirovecii was confirmed by documenting the organism with Wright Giemsa or Gram-Weigert stain or the cyst with Gomori methenamine silver or calcofluor white stain [1], which is the same methods with the previous study [18].

Statistical analysis

Data was presented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables and as numbers and percentages for categorical variables. The baseline and clinical characteristics on ICU admission were compared between the PCP group and the non-PCP group using the Mann-Whitney U test (for continuous variables) and the Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher exact test (for categorical variables).

To determine the sample size needed for the validation of our prediction model [20], we based our calculations on the test characteristics of the PCP score. For a ROC curve area of 0.8, a power (type II error) of 80% and an α (type I error) of 0.05, the sample size required for our study was 103 (8 from the positive group and 95 from the negative group). This was calculated using MedCalc statistical software.

The predictive ability of PCP score was assessed with ROC curve analysis for both the discrimination (via the C index) and calibration (using Hosmer–Lemeshow statistics) of the score [21]. Univariable logistic regression analysis was performed to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) of each variable in the PCP score. The ORs of each variable were reported with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR+ and LR-, respectively) were calculated for the PCP score. All variables were analysed using R Statistical Software (Version 3.2.5; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Study population

For this study, 141 haematology cases were admitted to the ICU due to ARF. They all underwent BAL and/or TBLB for aetiologic explorations. Amongst all cases, 13 (9.2%) were diagnosed of PCP. Baseline characteristics of the patients are summarised in Table 1. The median age of the patients was 58.0 (IQR 49.0–65.0) years, and 90 (63.8%) patients were male. There were 73 (51.8%) lymphoproliferative diseased cases and the most common haematological disorder was acute/chronic myeloid leukaemia (n = 44, 31.2%) followed by non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n = 50, 33.6%). Amongst all cases, 42 (29.8%) received an allogenic stem cell transplantation and 19 (13.5%) received an autologous stem cell transplantation. Sixty-three (44.7%) patients received systemic steroid treatment with a median prednisolone-equivalent dose of 44.5 (35.1–51.3) mg/day. Thirty-two (22.7%) cases received T-cell immunosuppressors and six (4.3%) cases received immune checkpoint inhibitors. However, only 30 (21.3%) cases received anti-PCP prophylaxis.

The clinical characteristics on ICU admission are displayed in Table 2. The median duration from symptoms to ICU admission was 4.0 (2.0–8.0) days. Amongst all cases, 137 (91.9%) had hypoxaemia requiring mechanical ventilation (n = 88, 59.1%) or high-flow nasal cannula support (n = 49, 32.9%). Thirty-nine (26.2%) cases needed vasopressor support, five (3.4%) needed renal replacement therapy and one needed extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (0.7%). The median initial SOFA score on ICU admission was 7.0 (4.0–9.0).

Performance of the PCP score

The area under the ROC curve was 0.535 (95% CI, 0.449–0.620), indicating no discriminatory ability in our haematology patients with ARF (Table 3, Fig. 2). Comparisons of PCP scores between PCP and non-PCP groups are illustrated in Fig. 3, but no significant difference was observed (P = 0.679). Of 13 patients, 7 (53.8%) received a PCP score of 3.0 or higher. When using a cut-off PCP score value of 3.0, a sensitivity of 38.5% (95% CI, 13.9–68.4) and a specificity of 7.03% (95% CI, 61.6–78.1) were obtained. The negative predictive value was 58.8% and the positive predictive value was 59.8% for a 10% prevalence of PCP. Performances of other cut-off values are reported in Table 4.

All variables of the PCP score were compared between the PCP and the non-PCP groups (Table 5). There was no significant difference between the two groups. In addition, the results of univariable analysis (using logistic regressiion model) of variables in the PCP score also showed no significant difference between the two groups.

Discussion

Over the last decade, there has been a substantial decline in PCP-related mortality rates among HIV-positive patients. Conversely, there is an increasing mortality rates associated with PCP in HIV-negative patients [14, 15]. In addition, a delay in anti-PCP treatment in these patients is associated with a higher mortality rate [13, 16]. This finding suggests that empiric therapy for PCP should be initiated in patients with high clinical suspicion for PCP. Unfortunately, there is no clinical tool that rapidly identifies patients at risk of PCP. Therefore, a high index of suspicion using patient history and clinical presentation, are key factors in early diagnosis of PCP [22]. However, the clinical picture varies individually as the general hallmarks (fever, shortness of breath and diffuse infiltrates) of this disease do not consistently occur, especially in its early course [23]. Therefore, clinical diagnosis is complicated because no combination of symptoms, signs, blood chemistries and/or radiographic findings is specific for PCP [24].

Recently, Azoulay et al. suggested a multivariable predictive model to improve the early diagnosis of PCP in haematology patients with ARF requiring ICU admission [18]. Variables included in the model were age, lymphoproliferative disease, anti-PCP prophylaxis, number of days between onset of respiratory symptoms and ICU admission, shock, chest radiograph pattern, and pleural effusion. Higher scores, were associated with lymphoproliferative disease, no anti-PCP prophylaxis, more than a three-day duration between onset of respiratory symptoms and ICU admission, and no alveolar pattern on radiography. Meanwhile lower scores were associated with those patients over 50 years of age, shock, and pleural effusion. Specificity for PCP was 88%, and the negative predictive value was 97%. Calibrations and discriminations were good (area under the curve, 0.80 in the derivation cohort and 0.83 in the validation cohort).

However, there are several questions regarding the variables used in the final model. Firstly, those patients over the age of 50 years were associated with lower scores meaning a lower risk of PCP. The authors described these points to be in line with older patients receiving less frequently high-dose chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation. These conditions put patients at high risk for PCP. However, the majority of haematologic malignancies are diagnosed in elderly patients and the decision to treat might not only be determined by age, but also by combining performance and frailty [25, 26]. In addition, previous reports showed an association between age > 60 years and pulmonary Pneumocystis colonisation, especially in patients with rheumatoid arthritis [27, 28]. Secondly, chest X-ray findings of PCP are non-specific and sometimes normal. In some cases, PCP presents bilateral, symmetric opacities in an interstitial or alveolar pattern on a chest X-ray. This is associated with an increased frequency of spontaneous pneumothorax [23, 29, 30]. Therefore, high resolution computed tomography (known to be the most reliable imaging technique for the detection and differential diagnosis of PCP), is recommended in immunocompromised patients, complementing either a negative or a vague chest X-ray [31].

Ideally, critically ill patients should be admitted in the ICU as soon as possible to receive the best appropriate care. However, delays in admission are common due to triage, diagnostic and logistic reasons [32,33,34]. Therefore, the duration between respiratory symptom onset and ICU admissions vary depending on each hospital’s policy and ICU bed availability. Our study also showed delayed ICU admissions (5 days versus 10 days in the PCP group). In addition, PCP patients presented more shock (22.4% versus 38.5% in the PCP group) and pleural effusion (5.2% versus 23.1%) in our cohort which are inconsistent with the PCP scores in Azoulay et al. These results are explained by the delayed ICU admission in our cohort.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first external validation of the PCP score, with varying predictive results in haematology patients from the Korean cohort. However, there were several potential limitations to our study. Firstly, although the sample size was larger than a priori (which was adequately powered to obtain the significant of an area under ROC curve of 0.8), it was relatively small compared to the original study. However, post hoc power analysis revealed that the observed power was 96.4% with a 9.2% prevalence of PCP in our cohort. Thus, the results are adequately powered to rule out the possibility of false-negative findings. Secondly, the diagnosis of PCP was confirmed by the identification of the organism in BAL fluid or lung tissue only. The diagnostic strategy for PCP now usually combines non-invasive diagnostic tests and PCR testing of BAL fluid. However, quantitative PCR was not yet available in Korea. Therefore, patients with positive PCR related to colonisation were considered as not having PCP in this study.

Conclusion

From the analysis of the two cohorts from designated haematology centres in Korea, the PCP score were not useful to predict the risk of PCP in haematology patients. Further prospective studies are needed before the score can be implemented into routine clinical practice for the early diagnosis of PCP in haematology patients.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Abbreviations

- ARF:

-

Acute respiratory failure

- BAL:

-

Bronchoalveolar lavage

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- LR:

-

Likelihood ratio

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PCP:

-

Pneumocystis pneumonia

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- TBLB:

-

Transbronchial lung biopsy

References

Thomas CF Jr, Limper AH. Pneumocystis pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2487–98.

Festic E, Gajic O, Limper AH, Aksamit TR. Acute respiratory failure due to pneumocystis pneumonia in patients without human immunodeficiency virus infection: outcome and associated features. Chest. 2005;128:573–9.

Ponce CA, Gallo M, Bustamante R, Vargas SL. Pneumocystis colonization is highly prevalent in the autopsied lungs of the general population. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:347–53.

Coyle PV, McCaughey C, Nager A, McKenna J, O'Neill H, Feeney SA, et al. Rising incidence of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia suggests iatrogenic exposure of immune-compromised patients may be becoming a significant problem. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61:1009–15.

Azoulay E, Mokart D, Kouatchet A, Demoule A, Lemiale V. Acute respiratory failure in immunocompromised adults. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7:173–86.

Kaplan JE, Hanson D, Dworkin MS, Frederick T, Bertolli J, Lindegren ML, et al. Epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus-associated opportunistic infections in the United States in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(Suppl 1):S5–14.

Palella FJ Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV outpatient study investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:853–60.

Sepkowitz KA, Brown AE, Telzak EE, Gottlieb S, Armstrong D. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia among patients without AIDS at a cancer hospital. JAMA. 1992;267:832–7.

Sepkowitz KA. Opportunistic infections in patients with and patients without acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1098–107.

Zahar JR, Robin M, Azoulay E, Fieux F, Nitenberg G, Schlemmer B. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in critically ill patients with malignancy: a descriptive study. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:929–34.

Gaborit BJ, Tessoulin B, Lavergne RA, Morio F, Sagan C, Canet E, et al. Outcome and prognostic factors of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in immunocompromised adults: a prospective observational study. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9:131.

Fillatre P, Decaux O, Jouneau S, Revest M, Gacouin A, Robert-Gangneux F, et al. Incidence of Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia among groups at risk in HIV-negative patients. Am J Med. 2014;127:1242 e11–7.

Roux A, Canet E, Valade S, Gangneux-Robert F, Hamane S, Lafabrie A, et al. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with or without AIDS. France Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1490–7.

Salzer HJF, Schafer G, Hoenigl M, Gunther G, Hoffmann C, Kalsdorf B, et al. Clinical, diagnostic, and treatment disparities between HIV-infected and non-HIV-infected Immunocompromised patients with Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia. Respiration. 2018;96:52–65.

Avino LJ, Naylor SM, Roecker AM. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in the non-HIV-infected population. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50:673–9.

Li MC, Lee NY, Lee CC, Lee HC, Chang CM, Ko WC. Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia in immunocompromised patients: delayed diagnosis and poor outcomes in non-HIV-infected individuals. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2014;47:42–7.

Ko RE, Na SJ, Huh K, Suh GY, Jeon K. Association of time-to-treatment with outcomes of Pneumocystis pneumonia with respiratory failure in HIV-negative patients. Respir Res. 2019;20:213.

Azoulay E, Roux A, Vincent F, Kouatchet A, Argaud L, Rabbat A, et al. A multivariable prediction model for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in hematology patients with acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198:1519–26.

Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonca A, Bruining H, et al. The SOFA (sepsis-related organ failure assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the working group on sepsis-related problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:707–10.

Obuchowski NA, McClish DK. Sample size determination for diagnostic accuracy studies involving binormal ROC curve indices. Stat Med. 1997;16:1529–42.

Bewick V, Cheek L, Ball J. Statistics review 13: receiver operating characteristic curves. Crit Care. 2004;8:508–12.

Calderon EJ, Gutierrez-Rivero S, Durand-Joly I, Dei-Cas E. Pneumocystis infection in humans: diagnosis and treatment. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2010;8:683–701.

Roux A, Gonzalez F, Roux M, Mehrad M, Menotti J, Zahar JR, et al. Update on pulmonary Pneumocystis jirovecii infection in non-HIV patients. Med Mal Infect. 2014;44:185–98.

Carmona EM, Limper AH. Update on the diagnosis and treatment of Pneumocystis pneumonia. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2011;5:41–59.

Abel GA, Klepin HD. Frailty and the management of hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2018;131:515–24.

Arora M, Sun CL, Ness KK, Teh JB, Wu J, Francisco L, et al. Physiologic frailty in nonelderly hematopoietic cell transplantation patients: results from the bone marrow transplant survivor study. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1277–86.

Fritzsche C, Riebold D, Munk-Hartig A, Klammt S, Neeck G, Reisinger E. High prevalence of Pneumocystis jirovecii colonization among patients with autoimmune inflammatory diseases and corticosteroid therapy. Scand J Rheumatol. 2012;41:208–13.

Mori S, Cho I, Ichiyasu H, Sugimoto M. Asymptomatic carriage of Pneumocystis jiroveci in elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Japan: a possible association between colonization and development of Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia during low-dose MTX therapy. Mod Rheumatol. 2008;18:240–6.

Vogel MN, Vatlach M, Weissgerber P, Goeppert B, Claussen CD, Hetzel J, et al. HRCT-features of Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia and their evolution before and after treatment in non-HIV immunocompromised patients. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:1315–20.

DeLorenzo LJ, Huang CT, Maguire GP, Stone DJ. Roentgenographic patterns of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in 104 patients with AIDS. Chest. 1987;91:323–7.

Heitkamp DE, Albin MM, Chung JH, Crabtree TP, Iannettoni MD, Johnson GB, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria(R) acute respiratory illness in immunocompromised patients. J Thorac Imaging. 2015;30:W2–5.

Garrouste-Orgeas M, Montuclard L, Timsit JF, Misset B, Christias M, Carlet J. Triaging patients to the ICU: a pilot study of factors influencing admission decisions and patient outcomes. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:774–81.

Cosby KS. A framework for classifying factors that contribute to error in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:815–23.

Sprung CL, Danis M, Iapichino G, Artigas A, Kesecioglu J, Moreno R, et al. Triage of intensive care patients: identifying agreement and controversy. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:1916–24.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by a Samsung Medical Center grant (OTA1902901). The funding body played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

REK and JL conceived and designed the study, analysed the data and drafted this manuscript. SJN and NRJ contributed to the design of this study, analysis of the data and writing of the manuscript. SWK was a major contributor in statistical analysis. KJ conceived and designed the study, analysed the data, and wrote the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center (IRB No. 2019–077-187) and Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital (IRB No. KC20RISI0439) approved this study and waived the requirement for informed consent because of the observational nature of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ko, RE., Lee, J., Na, S.J. et al. Validation of the Pneumocystis pneumonia score in haematology patients with acute respiratory failure. BMC Pulm Med 20, 236 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-020-01279-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-020-01279-4