Abstract

Background

Relationships between low forced vital capacity (FVC), and morbidity have previously been studied but there are no data available for the Caribbean population. This study assessed the association of low FVC with risk factors, health variables and socioeconomic status in a community-based study of the Trinidad and Tobago population.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted using the Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) study protocol. Participants aged 40 years and above were selected using a two-stage stratified cluster sampling. Generalized linear models were used to examine associations between FVC and risk factors.

Results

Among the 1104 participants studied a lower post-bronchodilator FVC was independently associated with a large waist circumference (− 172 ml; 95% CI, − 66 to − 278), Indo-Caribbean ethnicity (− 180 ml; 95% CI, − 90 to − 269) and being underweight (− 185 ml; 95% CI, − 40 to − 330). A higher FVC was associated with smoking cannabis (+ 155 ml; 95% CI, + 27 to + 282). Separate analyses to examine associations with health variables indicated that participants with diabetes (p = 0∙041), history of breathlessness (p = 0∙007), and wheeze in the past 12 months (p = 0∙040) also exhibited lower post-bronchodilator FVC.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that low FVC in this Caribbean population is associated with ethnicity, low body mass index (BMI), large waist circumference, chronic respiratory symptoms, and diabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

More than one and a half centuries after Hutchinson’s design of a spirometer to determine the ‘capacity for life,’ the forced vital capacity (FVC) remains a good predictor of mortality and morbidity. It is related to all-cause mortality even in the general population [1, 2] and can predict it better than systolic blood pressure or body mass index (BMI) [3]. Studies from the developed world have also shown significant associations of FVC with cardiovascular disease [4, 5], cardiovascular events [6], sudden cardiac death [7], metabolic syndrome [8], diabetes [9, 10], and the progression of chronic kidney disease [11]. There are relatively few studies that have examined the risk factors for a low FVC though this has often been attributed to “normal” ethnic differences.

Few spirometry based studies have been conducted on the Caribbean population. These studies have focused on airway obstruction and were performed either in specialty clinics or hospital. Two of them showed low forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) or FVC associated with vascular disease [12, 13] and another, FVC with systemic inflammation in diabetic patients [14].

We studied FVC in a national community-based study of non-institutionalized adults aged 40 years and over and living in Trinidad and Tobago, using the Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) study methodology. We investigated potential risk factors as well as the relation of FVC to the health and socioeconomic status. Since the use of universal cut-offs to define abnormal spirometry is contentious [15], we have analysed FVC as a continuous variable to assess its associations, including those with age, sex and ethnicity. In addition, we also studied similar associations with pre-bronchodilator FVC; and pre and post-bronchodilator FEV1.

Methods

Setting

Trinidad and Tobago, a high human development indexed country in the Caribbean, has a uniquely diverse population of predominantly East Indian and African descent. More than half of the population aged 20 years or more (55.5% of males and 66.1% of females) are overweight and obese [16]. The country also possesses a high burden of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases which were determined as the top two causes of death and disability in 2016 (Data was sourced from the IHME GBD profile. http://www.healthdata.org/trinidad-and-tobago.).

Study design

A cross-sectional survey was conducted across the 15 administrative districts of Trinidad and Tobago, a country with about 1.3 million inhabitants including 39% aged 40 years and above [17]. The study was approved by the ethics committees of the Faculty of Medical Sciences of the University of the West Indies and the Ministry of Health, Trinidad and Tobago.

After obtaining consent, participants aged 40 years and above were asked to answer a core questionnaire focusing on respiratory symptoms, health status, activity limitation, use of healthcare services, and exposure to potential risk factors, such as cigarette smoke. The participants also performed spirometry if there were no contraindications for forced expiratory manoeuvres. Additional questionnaires on indoor air pollution and occupational exposures were administered before the post-bronchodilator spirometry manoeuvres. A wealth score, using a Mokken scale [18] was applied to differentiate the socio-economic status of individual participants. This score was calculated based on the ownership of 10 household assets.

Spirometry

Spirometry was performed according to the 1994 American Thoracic Society (ATS) criteria [19], using the Easy-One portable spirometer (ndd Medizintechnik; Zurich, Switzerland), with the participant in a seated position and pre and post-bronchodilator spirometry (15 min after administering 200 μg salbutamol via metered-dose inhaler with a valve spacer) performed following the BOLD methodology [20]. The difference between the largest and second largest FEV1 and FVC values of < 200 ml was considered as reproducible [20]. A plateau for at least one second after an exhalation time of at least 6 s was considered as a valid end-of-test criterion [19]. Spirometry data were transmitted electronically to the BOLD pulmonary function reading centre in London, where each spirogram was reviewed. A good spirometry had to meet ATS criteria for acceptability, including having at least three attempts, two of which were acceptable [21]. Spirometry technicians were continuously monitored and whenever their quality scores dropped below a pre-set level, they were asked to stop testing, and undergo retraining and recertification. Among the acceptable efforts, the best post-bronchodilator FEV1 and FVC values, even if they were from different curves were used for statistical analyses [19].

Sampling

Participants were selected using two-stage stratified cluster sampling. The study was based on the BOLD protocol that required a minimal sample size of 600 persons above the age of 40 years. The actual sample size, inflated to take into account an expected rate of non-response and unacceptable spirometry (20%) and the clustered nature of the sampling, was 1209 households. A total of 1469 eligible participants were identified from these households and invited to participate.

Statistical analyses

Chi-square tests were used to examine differences in categorical variables and Student’s t-test to examine differences in continuous variables. We checked for differences between responders and non-responders and between those with and without acceptable spirometry. Complex Samples General Linear Models (SPSS Version 25) were used to study associations between FVC and the risk factors. This enabled the application of the stratified cluster sampling structure of the data in the analysis. Weights were also used in the analyses. Base weights were calculated as the inverse of the probability of each participant’s selection. Final weights were determined by adjusting for the age and gender distribution of the national population, using census data.

Age, sex, height, and height-squared are strong predictors of lung function [22] and as these four variables accounted for 60.5% of FVC variance, they were entered as covariates in all analyses. Age squared was not a significant predictor in our analyses and was not used as a covariate. Separate analyses were conducted for each risk factor. All the risk factors that were significantly associated with FVC were subsequently entered in a final model to determine independent predictors. We also used General Linear Models to conduct separate regression analyses to examine associations between FVC and the various health status indicators, and respiratory symptoms. The Complex Samples Analysis module was also used to estimate the prevalence and 95% CI for chronic airflow obstruction.

Results

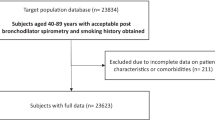

Out of a total eligible sample of 1469 individuals, 1394 completed the core questionnaire and undertook spirometry. Among them, 1104 successfully performed spirometry, as per the BOLD study quality control criteria (Fig. 1). Of the individuals approached 95% responded (95% response rate) and of these 97% agreed to participate (97% co-operation rate). Spirometry acceptability rate was 79%. Younger participants, those of Indo-Caribbean descent and those who had no chronic respiratory symptoms had higher rates of acceptable spirometry (p < 0.005 in all cases) (Additional file 1: Table S1). Smoking status, BMI and the presence of doctor-diagnosed respiratory disease did not show association with the participants’ spirometry acceptability.

The majority of participants were females (60%), and the sample’s age and ethnic distributions matched well with the recent national census data [17]. Overall, the sample comprised mainly persons of Asian or African ancestry (78%), with secondary or higher level education (53%), who were overweight or obese (70%), and who were exposed to indoor air pollutants (55%) (Table 1). Mean BMI and waist circumferences were higher among Afro-Caribbeans than Indo-Caribbeans (29.59 kg/m2 vs. 27.90 kg/m2; 97.71 cm vs. 95.71 cm, respectively; p < 0.03 in all cases). 27% of the participants gave a history of smoking, which was four times more prevalent in males than females. Among the smokers, more than half were current smokers and one third had also smoked cannabis. 85% of participants had ownership of eight or more of the household amenities in the inventory.

About one-third of the study participants mentioned at least one of the four symptoms - cough, phlegm, wheeze, and breathlessness in the past 12 months. Also, nearly 10% reported a doctor diagnosed respiratory disease (Table 2). 37% had at least one known co-morbidity, the most prevalent conditions being hypertension (28%) and diabetes (15%). Indo-Caribbeans had a higher diabetes prevalence than the Afro-Caribbeans and Mixed/ other ethnic groups (21, 10, and 12% respectively). This is the only health variable observed to be different between the ethnic groups. Gender differences in health status were noted in breathlessness, (p < 0.001) and doctor-diagnosed respiratory diseases (p = 0.03). In each case, the rates were higher in women than in men (Table 2).

Risk factors for low FVC

FVC values were higher in men than women (mean difference = 1070 ml; 95%CI = 991, 1148; p < 0.001). These values were also positively correlated with height (b = 0.052; 95%CI = 0.047, 0.056; p < 0.001) and negatively associated with age (b = − 0.026; 95%CI = − 0.031, − 0.021; p < 0.001).

The mean FVC and FEV1 values adjusted for age, sex, height, and height-squared are tabulated in Table 3 by the potential risk factors. There were significant post-bronchodilator FVC differences by ethnicity (p < 0.001), BMI group (p = 0.024), abnormal waist circumference (p < 0.001), abnormal waist-hip-ratio (p < 0.001), and whether they smoked cannabis (p = 0.004). Indo-Caribbeans showed lower mean FVCs than Afro-Caribbeans and other ethnic groups (Table 3 and Fig. 2). BMI presented a non-linear relation with low FVC. Underweight and obese subjects displayed lower FVCs than those with normal body habitus and overweight people. People with central obesity (abnormal waist circumference and waist-hip ratio) also showed lower FVCs. On the other hand, smokers of cannabis had higher FVC scores than persons who never smoked cannabis. Cigarette smoking status, history of pack-years, second-hand smoking, childhood exposure to smoking, indoor air pollutant exposure, and working in a dusty environment for more than 1 year were not associated with FVC values.

Multiple regression analysis of the risk factors that were significant after adjusting for age, sex, height, and height-squared indicated that post-bronchodilator FVC was lower in those with increased waist circumference (− 172 ml), Indo-Caribbean participants (− 180 ml) and those who were underweight (− 185 ml), and higher in those who smoked cannabis (+ 155 ml) (Table 4).

Risk factors for low pre-bronchodilator FVC were of similar significance to those for post-bronchodilator FVC except that indoor air pollution and levels of education were related to pre-bronchodilator FVC but not to post-bronchodilator FVC (Tables 3, 4 and Additional file 1: Table S2).

FVC and health variables

The mean adjusted FVC and FEV1 scores by the various symptoms and health status variables are listed in Table 5. Participants with known diabetes (p = 0.041), with a history of breathlessness (p = 0.007), and wheeze in the past 12 months (p = 0.040) exhibited lower FVC. Diagnosed respiratory disease, hypertension, cardiac disease, history of cough or phlegm, hospitalization before the age of 10 years, and family history of airway disease were not associated with FVC.

Risk factors for low FEV1

Low post-bronchodilator FEV1 was also independently associated with Indo-Caribbean ethnicity (− 125 ml) and abnormal waist circumference (− 108 ml) (Additional file 1: Table S4). In contrast to FVC, low FEV1 showed an independent association with indoor air pollutant exposure (− 95 ml for all three exposures) but did not show a relation with BMI and cannabis smoking. Further, pre-bronchodilator FEV1 showed associations with abnormal waist-hip ratio (− 69 ml) and highest level of education (+ 168 ml for university education).

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first published study of lung function in the general population of a Caribbean country and provides new information on the associations of FVC with participant demographics, socio-economic status and morbidity. We found lower FVCs among the Indo-Caribbean population, those with a low BMI and with central obesity. Individuals with a low FVC had more respiratory symptoms.

We observed low FVCs among Indo-Caribbeans compared to Afro-Caribbeans in our study by abut 8% despite the similar prevalence of abnormal waist circumference (57.0% vs. 58.7%; p = 0.751) and a lower prevalence of obesity (30.0% vs. 41.8%; p = 0.008), (Table 6). The lower volumes among Indo-Caribbeans compared with the population of African descendant were consistent with the results from Global differences in lung function by region Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study [23]. This contrasts with the recently published Canadian Health Measures Survey reference values [24] which showed higher FVCs among those of South Asian compared with those of African descent.

FVC in our population showed a nonlinear relation with BMI, comprising low volumes among those with both low and high BMI. Obesity and abnormal waist circumference related reduction in vital capacity can be explained by restriction of inspiration. Obesity-associated reduction in FVC has been observed in many studies and has been attributed to an increased impedance of the chest wall [25,26,27]. Studies have also shown that a 1 cm increment in waist circumference can decrease FVC by 13 ml [28]. Waist circumference is considered as a superior indicator of intra-abdominal fat [29] and may be a good gauge of its effect on diaphragm function and other ventilatory mechanics. When we adjusted FVC measures for both BMI and waist circumference the association of low FVC with a high BMI disappeared and that with waist circumference was essentially unchanged, suggesting that the link between a low FVC and a high BMI is mediated largely through mechanical effects of an increase in intra-abdominal fat. The association of a low FVC with a low BMI, however, was strengthened in the adjusted model, suggesting a more direct association. Low vital capacities have also been reported to be associated with low birth weight [30], though we have no estimate of birth weight in this population.

An increased FVC among cannabis smokers has also been reported in previous studies [31,32,33]. The exact cause for this increase is unclear but could reflect a “healthy smoker” effect, those with poor lung function being less likely to take up smoking cannabis. The effect of cannabis on FVC and the lack of association with FEV1 could be explained by training effects on the respiratory muscles with the habitual deep inhalations during cannabis smoking, and the likely acute bronchodilatory effects of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) [34]. These findings warrant careful interpretation given the potential adverse public health implications of long-term cannabis use including emphysematous bullae [35] and a twofold increased odds of obstructive lung disease [32]. Apart from cigarette smoking, the statistically nonsignificant associations with environmental factors such as exposure to indoor air pollution or solid fuel and working in a dusty environment on FVC have been observed in other studies as well [36].

We found that participants who had a low FVC had a history of wheezing or shortness of breath. This relationship has been published in previous studies [37, 38]. A low FVC was also associated with comorbidities especially diabetes. Earlier studies have found that individuals in the lowest quartile for FVC are more likely to develop insulin resistance [8] and diabetes [9] over time. A meta-analysis of 40 publications has shown a significantly lower FVC and FEV1 with preserved FEV1/FVC ratio among diabetic patients [39].

Although low socioeconomic status and poor education have been associated with reduced ventilatory function and chronic lung disease, this was not found in the current study. This may be due to either high per capita gross domestic product (GDP US$ 17,879 in 2015) with minor economic inequalities (GINI index 40.3 in 2010) among the local community (Data was sourced from the IMF press release no. 17/423. http://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2017/11/06/pr17423-imf-executive-board-concludes-article-iv-consultation-with-trinidad-and-tobago) compared to other developing countries or ineffectiveness of the tools used to distinguish the economic variations in this population. Although the wealth scale that we used has been shown to have good reliability [18] and has been associated with educational attainment, the majority of the sample possessed eight or more out of ten household amenities. This was similar to the situation seen in wealthy countries like Saudi Arabia [40]. The scale may need customization.

Limitations of the current study include the cross-sectional nature of the research, reliance on self-reported data and limited tools to measure the socioeconomic variations in the local population. However, there were many strengths such as our high response and cooperation rates. The diverse and evenly distributed ethnic distribution in the population, which was reflected in the sample, allowed for the examination of ethnic differences. Other strengths included the application of robust BOLD methodology, sound participant sampling, and quality assured spirometry. Most importantly we avoided the arbitrary use of ‘normal’ values for lung function assessment.

Conclusions

Low FVC was associated with ethnicity, central obesity, chronic respiratory symptoms, and comorbidities like diabetes. Longitudinal studies are required to estimate the mortality and morbidity risk with diminished FVCs and also to compare the health effects of reduced FVC compared to reduced static lung volumes. Identifying individuals with low FVC may have clinical and public health importance and a better understanding of this condition and its origins is needed.

Abbreviations

- ATS:

-

American thoracic society

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BOLD:

-

Burden of obstructive lung disease

- FEV1:

-

Forced expiratory volume in one second

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- GDP:

-

Gross domestic product

- PURE:

-

Prospective urban rural epidemiology study

- THC:

-

Tetrahydrocannabinol

References

Burney PG, Hooper R. Forced vital capacity, airway obstruction and survival in a general population sample from the USA. Thorax. 2011;66(1):49–54.

Magnussen C, Ojeda FM, Rzayeva N, et al. FEV1 and FVC predict all-cause mortality independent of cardiac function — results from the population-based Gutenberg health study. Int J Cardiol. 2017;234:64–8.

Gupta RP, Strachan DP. Ventilatory function as a predictor of mortality in lifelong non-smokers: evidence from large British cohort studies. BMJ Open. 2017;7(7):e015381.

Schroeder EB, Welch VL, Couper D, et al. Lung function and incident coronary heart disease: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:1171–81.

Mannino DM, Davis KJ, Disantostefano RL. Chronic respiratory disease, comorbid cardiovascular disease and mortality in a representative adult US cohort. Respirology. 2013;18(7):1083–8.

Johnston AK, Mannino DM, Hagan GW, et al. Relationship between lung function impairment and incidence or recurrence of cardiovascular events in a middle-aged cohort. Thorax. 2008;63(7):599–605.

Kurl S, Jae SY, Kauhanen J, et al. Impaired pulmonary function is a risk predictor for sudden cardiac death in men. Ann Med. 2015;47(5):381–5.

Lee HM, Chung SJ, Lopez VA, et al. Association of FVC and total mortality in US adults with metabolic syndrome and diabetes. Chest. 2009;136(1):171–6.

Engström G, Hedblad B, Nilsson P, et al. Lung function, insulin resistance and incidence of cardiovascular disease: a longitudinal cohort study. J Intern Med. 2003;253(5):574–81.

Yeh HC, Punjabi NM, Wang NY, et al. Vital capacity as a predictor of incident type 2 diabetes: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(6):1472–9.

Sumida K, Kwak L, Grams ME, et al. Lung function and incident kidney disease: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(5):675–85.

Seemungal T, Harrinarine R, Rios M, et al. Obstructive lung disease in acute medical patients. West Indian Med J. 2008;57:7–14.

Thorington P, Rios M, Avila G, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among stable chronic disease subjects in primary care in Trinidad, West Indies. J Thorac Dis. 2011;3(3):177–82.

Pinto Pereira LM, Seemungal TAR, Teelucksingh S, et al. Restrictive pulmonary deficit is associated with inflammation in sub-optimally controlled obese diabetics. J Thorac Dis. 2013;5(3):289–97.

Linares-Perdomo O, Hegewald M, Collingridge DS, et al. Comparison of NHANES III and ERS/GLI 12 for airway obstruction classification and severity. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(1):133–41.

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study Lancet. 2013;384(9945):766–81.

Trinidad and Tobago 2011 population and housing census demographic report. Central statistical office, Ministry of planning and sustainable development, Government of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago.. Available from: http://cso.gov.tt/media/publications-documents/. [cited 2018 June 10]

Townend J, Minelli C, Harrabi I, et al. Development of an international scale of socio-economic position based on household assets. Emer Themes Epidemiol. 2015;12:13.

American Thoracic Society Statement. Standardization of spirometry, 1994 update. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(3):1107–36.

Buist AS, Vollmer WM, Sullivan SD, et al. The burden of obstructive lung disease initiative (BOLD): rationale and design. COPD. 2005;2(2):277–83.

Hankinson JL, Eschenbacher B, Townsend M, et al. Use of forced vital capacity and forced expiratory volume in 1 second quality criteria for determining a valid test. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(5):1283–92.

Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general US population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(1):179–87.

Duong M, Islam S, Rangarajan S, et al. Global differences in lung function by region (PURE): an international, community-based prospective study. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:599–609.

Coates AL, Wong SL, Tremblay C, et al. Reference equations for spirometry in the Canadian population. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(6):833–41.

Obaseki DO, Erhabor GE, Awopeju OF, et al. Reduced forced vital capacity in an African population. Prevalence and risk factors. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(5):714–21.

Kurth L, Hnizdo E. Change in prevalence of restrictive lung impairment in the U.S. population and associated risk factors: the National Health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 1988–1994 and 2007–2010. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2015;10:7.

Thyagarajan B, Jacobs DR Jr, Apostol GG, et al. Longitudinal association of body mass index with lung function: the CARDIA study. Respir Res. 2008;9:31.

Chen Y, Rennie D, Cormier YF, et al. Waist circumference is associated with pulmonary function in normal-weight, overweight, and obese subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(1):35–9.

Klein S, Allison DB, Heymsfield SB, et al. Waist circumference and cardiometabolic risk: a consensus statement from shaping America’s health: Association for Weight Management and Obesity Prevention; NAASO, the Obesity Society; the American Society for Nutrition; and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1647–52.

Saad NJ, Patel J, Burney P, et al. Birth weight and lung function in adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(6):994–1004.

Hancox RJ, Poulton R, Ely M, et al. Effects of cannabis on lung function: a population-based cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2010;35(1):42–7.

Kempker JA, Honig EG, Martin GS. The effects of marijuana exposure on expiratory airflow. A study of adults who participated in the U.S. National Health and nutrition examination study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(2):135–41.

Pletcher MJ, Vittinghoff E, Kalhan R, et al. Association between marijuana exposure and pulmonary function over 20 years. JAMA. 2012;307(2):173–81.

Tashkin DP, Shapiro BJ, Frank IM. Acute pulmonary physiologic effects of smoked marijuana and oral (Delta)9 -tetrahydrocannabinol in healthy young men. N Engl J Med. 1973;289(7):336–41.

Hii SW, Tam JDC, Thompson BR, et al. Bullous lung disease due to marijuana. Respirology. 2008;13(1):122–7.

Amaral AFS, Patel J, Kato BS, et al. Airflow obstruction and use of solid fuels for cooking or heating: BOLD results. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(5):595–610.

Grønseth R, Vollmer WM, Hardie JA, et al. Predictors of dyspnoea prevalence: results from the BOLD study. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(6):1610–20.

Soriano JB, Miravitlles M, García-Río F, et al. Spirometrically-defined restrictive ventilatory defect: population variability and individual determinants. Prim Care Respir J. 2012;21(2):187–93.

van den Borst B, Gosker HR, Zeegers MP, et al. Pulmonary function in diabetes: a metaanalysis. Chest. 2010;138(2):393–406.

Townend J, Minelli C, Mortimer K, et al. The association between chronic airflow obstruction and poverty in 12 sites of the multinational BOLD study. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(6):1601880.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the BOLD central office, Imperial College, London for guidance and spirometry quality control, BOLD Trinidad and Tobago Steering Committee for technical advisory support, The Central Statistical Office (CSO) Trinidad and Tobago for providing population sampling support, and The Thoracic Society of Trinidad and Tobago (TSOTT) for professional collaboration.

Funding

The BOLD Trinidad and Tobago study was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Health, the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, and a Research and Development grant from The University of the West Indies, St. Augustine. Some financial or other support was also obtained from Astra-Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Glaxo Smith Kline and Novartis. The BOLD coordinating centre was funded by the Wellcome Trust (085790/Z/08/Z). The funding bodies played no role in study design and data collection, interpretation of data or writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study hypothesis was formulated by TS. The study was designed by TS and PB. Study was coordinated and data was collected by FL and LC. The data was analysed by DS. The findings were interpreted and manuscript was drafted by TS, SS, DS and FL. The first draft of the manuscript was produced by S.S. All authors critically revised the report and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was granted by the ethics committees of the Faculty of Medical Sciences of the University of the West Indies and the Ministry of Health, Trinidad and Tobago. All participants signed the written consent to participate.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Supplementary material. (DOCX 49.6 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sakhamuri, S., Lutchmansingh, F., Simeon, D. et al. Reduced forced vital capacity is independently associated with ethnicity, metabolic factors and respiratory symptoms in a Caribbean population: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pulm Med 19, 62 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-019-0823-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-019-0823-9