Abstract

Background

This study examined a) trends in overweight/obesity, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), and screen time (ST) among Czech adolescents over a 12-year study period (2002–2014) in relation to family affluence (FA) and b) correlates of adolescent overweight/obesity from different FA categories.

Methods

A nationally representative sample of 18,250 adolescents (51.4% girls) aged 10.5–16.5 years was drawn from the Czech Health Behaviour in School-aged Children questionnaire-based surveys in 2002, 2006, 2010, and 2014. Using the FA scale, the socioeconomic status (SES) of the respondents’ families was assessed. SES-stratified trends in the prevalence of overweight/obesity meeting the MVPA (≥60 min/day), and ST (≤2 h/day) recommendations were assessed using logistic regression.

Results

A trend-related significant increase (p < 0.05) in the prevalence of overweight/obesity was observed in low−/medium-FA boys and medium−/high-FA girls. Unlike in high-FA adolescents, a significant decrease was revealed in the rates of meeting the MVPA recommendation in low-FA boys (28.9%2002 → 23.3%2014, OR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.59–0.95, p < 0.05) and girls (22.3%2002 → 17.3%2014, OR = 0.73, 95% CI = 0.57–0.92, p < 0.01). A significant (p < 0.001) trend-related increase in excessive ST was evident in adolescents regardless of gender and FA category. Generally, girls and older adolescents had lower odds of overweight/obesity than boys and 11-year-old adolescents. While in the high-FA category of adolescents, achieving 60 min of MVPA daily and the absence of excessive ST on weekdays significantly (p < 0.01) reduced their odds of being overweight/obese, in low-FA adolescents this was not the case.

Conclusions

High rates of overweight/obesity and a poor level of daily MVPA among low-FA children provide disturbing evidence highlighting the necessity of public health efforts to implement obesity reduction interventions for this disadvantaged population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Obesity and obesity-related diseases are among the most expensive economically treatable diseases in children and youth [1, 2]. After years of a consistent increase in the prevalence of childhood obesity, there are some indices of a possible decline in the prevalence of obesity among pre-schoolers, children, and adolescents [3,4,5]. However, this ‘break’ in the obesity epidemic needs to be interpreted with caution [6], since the prevalence of extreme forms of obesity in children and adolescents continues to increase [7, 8]. In addition, in economically developed countries the peak prevalence of obesity is moving from middle adult age to younger age cohorts [9]. Childhood obesity is the focus of public health efforts and the accurate determinate of obesity-vulnerable groups of children and youth is a key condition for the development and implementation of obesity reduction interventions. Age, gender, socioeconomic status (SES), ethnicity, level of physical activity (PA) and sedentary behaviour, eating habits, the duration of sleep, and behavioural problems should be taken into account [10, 11].

Repeatedly observed positive links between childhood overweight/obesity and unhealthy eating habits [12,13,14] or low PA or high sedentary behaviour [15,16,17,18,19] are influenced by the SES of children’s families [20, 21]. SES in children and adolescents is commonly estimated using parental education or parental income [15, 21]. In the high-income countries (e.g. the U.S., Germany) high levels of adolescents’ PA and participation in sport are significantly associated with a higher level of parental education [15, 21, 22], family income [15, 21], and the adolescents’ level of education [23], regardless of their gender [15, 21]. Moreover, European adolescents with parents with lower levels of education spend more time on sedentary activities than adolescents whose parents have higher education [24]. Similarly, children from families with a low household income show lower levels of PA and spend more time being sedentary than children from families with a high household income [25, 26]. However, at the beginning of the third millennium (2001/2002) the effect of family affluence (FA) was significant in relation to MVPA neither in Czech adolescents nor in adolescents from other middle- or low-income European countries – Greenland, Ireland, Malta, Ukraine, and Macedonia [27].

Probably, adolescents from low- and middle-income European countries tend to repeat behavioural patterns that had previously been witnessed in adolescents from the Western high-income countries, e.g. a decrease in PA, increased sedentary behaviour, screen-based activities, and an increase in the excessive consumption of sweetened beverages and fast food intake [28, 29], which consequently leads to increased rates of overweight and obesity [10,11,12]. In addition, across the low- and middle-income countries of Eastern, Southern, and Central Europe (e.g. Belarus, Latvia, the Republic of Moldova, Croatia, Greece, Malta, Romania, Serbia, Slovenia, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia) a rapid increase in overweight/obesity and obesity-related diseases has been projected to occur by 2030 [30] or by 2050 [30, 31]. Moreover, out of the above-mentioned European countries, the largest reduction in diabetes and coronary heart diseases, with a 5% fall in the body mass index (BMI) of the population by 2030, is modelled in Croatia, the Czech Republic, Latvia, Serbia, and Slovakia [30, 31]. Therefore, it is necessary to improve the surveillance of trends in obesity, as well as obesity-related practices that are effective in reducing body fat in low- and middle-income European countries.

Previous ‘Health Behaviour in School-aged Children’ (HBSC) trend studies point to an increase in the prevalence of overweight/obesity among adolescents from low- and middle-income European countries between 2002 and 2010 [32, 33], which, in the Czech Republic, continued until 2014 [16]. In the 2002–2010 period, mixed results were found in trends to achieve of at least 60 min of MVPA per day in adolescents from low- and middle-income European countries [34]. However, the same pattern of behaviour in adolescent girls and boys was found in screen time (ST) trends between 2002 and 2010 – a slight decline in television viewing (TV), more than offset by a sharp increase in computer use (PC) [35]. Moreover, excessive ST behaviour (more than two hours per day) and insufficient PA (less than 60 min of MVPA per day) significantly increase the chance of overweight/obesity in Czech adolescents [16]. However, it is still not known whether the trends in overweight/obesity, PA, and ST vary according to the SES of children’s families.

Therefore, the main aim of this study is to describe trends in the prevalence of overweight/obesity and in achieving MVPA recommendations (≥60 min per day) and non-excessive ST (≤2 h per weekday or weekend day) among Czech boys and girls over a 12-year study period (2002–2014) in relation to the SES of their families. Furthermore, the study aims to analyse the correlates of overweight/obesity in adolescents from different SES categories.

Methods

HBSC study

The HBSC study is a World Health Organization (WHO) collaborative cross-national study carried out by research teams in 47 countries and regions across Europe, North America, and Asia. It aims to uncover adolescents’ health and health-related behaviours, and provides insights into the adolescents’ lifestyle. A standardized international research protocol was followed in all the participating countries to ensure consistency in survey instruments, data collection, and processing procedures [36]. Since 1985/1986 data has been collected at four-year intervals using nationally representative samples of 11-, 13-, and 15-year-old adolescents within each participating country. The questionnaire survey assesses a wide range of self-reported health behaviours and lifestyle-related outcomes.

Sample and data collection

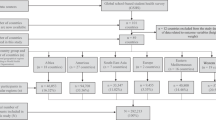

The data for the present analyses is based on a nationally representative randomized cluster (school level) sampling procedure. The sample consists of reports from 18,250 adolescents (2002: n = 4912 (52.3% girls), 2006: n = 4629 (49.6% girls), 2010: n = 4121 (51.3% girls), and 2014: n = 4588 (52.4% girls)) with complete data for weight status, PA, ST, and FA variables (Table 1). The trained researchers administered the data collection during one morning teaching lesson in the classroom. The participation of the adolescents in each data collection cycle was voluntary, and the respondents were assured of anonymity and the confidentiality of their responses. To ensure anonymity, after completing the survey the students were instructed to insert the questionnaire in an envelope, seal it, and hand it over to the researchers. The school response rate among the surveys varied from 75% to 99% and the adolescent participants’ response rate in each of the four surveys exceeded 80%. Participating adolescents were predominantly white Caucasian (>98%), which is representative of the ethnic demographics of the Czech Republic [37]. All the survey procedures for each data collection cycle were documented and can be downloaded from http://www.hbsc.org/methods/index.html. This study was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Physical Culture, Palacký University Olomouc, No. 9/2016 on 4th March 2016.

Survey items

Weight status

Three weight status-related items (body weight, body height, and chronological age) were used to calculate the prevalence of normal body weight and overweight/obesity of the participants. The actual body weight and height of the adolescents were self-reported in the HBSC questionnaire. The chronological age was calculated as the difference between the date of the data collection and the self-reported month and year of birth of the participating adolescents. Body weight status (normal weight and overweight/obesity) was classified on the basis of the WHO percentile Body Mass Index (BMI) charts for 5–19-year-old boys and girls [38]. Overweight and obesity were represented by 85%–97% and >97%, respectively, on age-differentiated percentile BMI charts [39, 40]. The BMI derived from the self-reported body weight and height demonstrated good diagnostic ability for identifying overweight/obesity in the 6–18-year-old children (sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values ranged from 0.83 to 0.98) [41]. Self-reported body weight and body height demonstrated almost perfect agreement with the measured values and were substantially able to identify overweight-to-obese children in epidemiological studies [41, 42].

Physical activity

MVPA patterns was assessed for the purposes of analyses of trends. MVPA was examined by a single question, ‘Over the past 7 days, on how many days were you physically active for a total of at least 60 minutes per day?’ The question was introduced by an explanatory text defining MVPA as any activity that increases the heart rate and makes a person get out of breath some of the time, with examples provided. The response categories were consistent among all the survey cycles and ranged from ‘0 days’ to ‘7 days’. For the analysis of trends in achieving current MVPA recommendations (≥60 min per day – [43, 44]) a dichotomous outcome variable was created. Adolescents who self-reported that they had been active for at least 60 min of MVPA on each of the past seven days were classified as meeting the MVPA recommendations.

The assessment of self-reported MVPA during the past seven days in adolescents was originally developed and validated against seven-day continuous measurement with an accelerometer (rMVPA = 0.40 p < 0.01) [45]. Recent studies support the validity of self-reported past-seven-days total PA and MVPA (r = 0.49 p < 0.01 correlation with seven-day continuous monitoring with an Actigraph accelerometer) [46], with almost perfect test-retest stability of the MVPA item in 11–15-year-old Polish (ICC = 0.98) and Chinese (ICC = 0.82) adolescents [47, 48].

Screen time

Two ST-related components (TV viewing and PC use) were assessed in a comparable manner in all the four-year cycles of data collection between 2002 and 2014. TV viewing during leisure time was examined using one question divided into weekdays and weekends: ‘About how many hours a day do you usually watch television (including DVDs and videos) in your free time?’ The response options were consistent among all the data collection cycles and included nine response categories: ‘None at all’, ‘About half an hour a day’, ‘About 1 h a day’, ‘About 2 h a day’, ‘About 3 h a day’, ‘About 4 h a day’, ‘About 5 h a day’, ‘About 6 h a day’, and ‘About 7 or more hours a day’. In 2002, PC time was assessed by the question: ‘About how many hours a day do you usually use a computer (for playing games, e-mailing, chatting, or surfing the Internet) in your free time?’ During the 2006–2014 surveys, this single question was subdivided into two to better reflect the wider accessibility of new technologies. Adolescents were asked to report separately for weekdays and weekends: i) ‘About how many hours a day do you usually use a computer for chatting online, Internet, e-mailing, homework, and so forth in your free time?’; and ii) ‘About how many hours a day do you usually play games on a computer or games console (PlayStation, Xbox, GameCube, etc.) in your free time?’ Both PC time-related questions used the same categories of possible answers as TV viewing. The outcome variable, the amount of daily ST, is the sum of daily TV viewing and PC use. In line with the current recommendations [49], daily ST was dichotomized as follows: two or fewer hours vs. more than two hours of ST per day. Two or more hours per day of ST is classified as excessive [49].

The validity of self-reported ST questions for the past seven days has been proved in comparison with 7-day 24-h diaries among 11-to-15-year-old adolescents both on weekdays (r = 0.39–0.46, p < 0.001) and at weekends (r = 0.37–0.47, p < 0.001) [50, 51]. The test-retest stability of the TV viewing and PC use question has been repeatedly verified for weekdays (ICCTV = 0.54–0.72, ICCPC = 0.33–0.82) and weekend days (ICCTV = 0.58–0.68, ICCPC = 0.33–0.66) [47, 48, 50, 52]. Adolescents do not have a systematic tendency to under- or over-report their amount of daily ST, and the current TV and PC time-related questions appear to have adequate reliability and validity for behavioural epidemiological studies [47, 48, 50,51,52].

Family affluence scale

Because of the repeatedly uncovered gender-related differences in the prevalence of overweight/obesity [32], PA patterns [33, 34], and ST behaviour [35] of adolescents, all the trend analyses were stratified according to the gender of the adolescents. Parental SES has also been shown to correlate with teenagers’ weight status [11, 20], PA [25, 26], and ST [51], and therefore we stratified the analysis further by FA as an indicator of SES.

The FA scale was developed within the HBSC research network as a measure of parental SES [53]. The FA scale, including easily answerable questions that reflect material affluence, has proved to be a useful indicator of family material affluence [53]. Between 2002 to 2010, four items were included to determine FA: car ownership (No = 0; One = 1; Two or more = 3), number of computers (None = 0; One = 1; Two = 2; Three or more = 3), family holidays in the past year (Never = 0; Once = 1; Twice = 2; Three or more times = 3), and having one’s own bedroom (No = 0; Yes = 1) [53]. In 2014, the FA scale was updated with respect to the changes in the social environment [44, 54]. Two new FA-related items – dishwasher ownership (No = 0; Yes = 2) and number of bathrooms (None = 0; One = 1; Two = 2; Three or more = 3) were added to the existing FA scale. The response codes to these items were summed and treated as a composite sum score. For the trend analyses, three categories of FA (“low”, “medium”, and “high”) were derived from the composite sum score. Between 2002 and 2010 the FA categories correspond to tertiles of the sum score (“low” = 0–3; “medium” = 4–6, “high” = 7–9) and in 2014 as follows: “low” = 0–6, “medium” = 7–9, and “high” = 10–13 [14]. The FA scale provides a valid assessment of household material affluence among families with adolescents [53] with documented high validity (kappa coefficients 0.41%–0.74%, 76.2%–88.1% agreement) and moderate reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.58) between children’s and parents’ responses on the FA scale-related items [55,56,57,58].

Data analysis

Descriptive data for all the items analysed is presented as percentages split by gender per each survey year. Because TwoStep cluster analysis found no indicator for clustering by school or class in the outcome variables that were analysed in any of the four survey cycles, we conducted single-level analyses of the trend-related variables. The time trends of the outcome variables between 2002 and 2014 were determined using logistic regression analysis (Enter method), with the 2002 survey as the reference category. The chi-square tests compared the prevalence of overweight/obesity, prevalence in achieving MVPA, and ST recommendations in 2014 between groups of children with low and high FA separately for boys and girls. The correlates of overweight/obesity in relation to FA were estimated using the multiple logistic regression analysis Enter method. The regression parameters were based on the odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows v.22 software (IBM Corp. Released 2013. Armonk, NY, USA) was used for data management and all statistical analyses. A minimum alpha level of 5% was taken for all the statistical analyses.

Results

Gender and family affluence-related trends in overweight/obesity, PA, and ST

A trend-related significant increase (>5 percentage points (p.p.)) in the prevalence of overweight/obesity was observed in low−/medium-FA boys and medium−/high-FA girls (Table 2). The highest prevalence of overweight/obesity in the 2013/2014 HBSC data collection was observed in the category of low-FA adolescents (boys 29.0% and girls 14.4%). Conversely, the lowest prevalence of overweight/obesity in 2014 was found in boys (20.1%) and girls (9.1%) in the high-FA category (Table 2). The differences in the prevalence of overweight/obesity in adolescents from the low- and high-FA categories were a significant for both genders in 2014.

Regarding 60 or more minutes of MVPA daily, similar gender-related trend patterns were found between 2002 and 2014. However, different trend-related patterns of MVPA were detected in different FA category of adolescents. Except for adolescents from the high-FA category, for all the other boys and girls, a significant decrease in the achievement of ≥60 min of daily MVPA was revealed. However, in the percentage of achievement of MVPA recommendations in the last cycle of data collection (2013/2014), we discovered similar differences between adolescents from the low- and high-FA categories.

In 2014, the adolescents in the high-FA category show a significantly higher proportion in both MVPA than the adolescents in the low-FA category (>6 p.p) (Table 2). While FA-related differences are apparent in MVPA trend patterns between 2002 and 2014, a significant (p < 0.001) decrease in non-excessive ST (>10%) is obvious in the case of ST between 2002 and 2014, irrespective of gender, FA category, and the type of day of the week (Table 2). The most noticeable decline in non-excessive ST (≈20 p.p.) was found in low- and high-FA girls at weekends. However, when differences in non-excessive ST among the adolescents from the low- and high-FA categories were compared, gender-related differences were found between 2002 and 2014. While in the boys, the difference in non-excessive ST was gradually mitigating on weekdays (low FA-high FA: 8.8 p.p. 2002, 6.5 p.p. 2006, 3.7 p.p. 2010 and 3.0 p.p. 2014), the difference in non-excessive ST at weekends gradually increased in the girls (low FA-high FA: 2.3 p.p. 2002, 2.4 p.p. 2006, 3.2 p.p. 2010 and 4.5 p.p. 2014) (Table 2). In the last year of data collection, in 2014, more than 90% of the boys and more than 80% of the girls spent more than two hours per weekend day on ST, compared to 2002, when less than 80% of the boys and less than 68% of the girls exceeded the threshold of excessive ST. In addition, in 2014 the relative rates of boys reporting non-excessive ST in all the FA categories were barely half compared with the girls’ rates in, both on weekdays and at weekends (Table 2).

Correlates of overweight/obesity in relation to family affluence

We found that girls and older adolescents had lower odds of overweight/obesity than boys and 11-year-old schoolchildren, respectively, in all the FA categories. However, the MVPA and ST correlates of adolescents’ overweight/obesity varied according to different FA categories. In the high-FA category of adolescents, achieving 60 min of MVPA daily or the absence of excessive ST on weekdays significantly reduced their odds of overweight/obesity. In contrast, only non-excessive ST at weekends was significantly associated with lower odds of overweight/obesity in the low-FA category of adolescents (Table 3). The differences in the odds of the prevalence of overweight/obesity in adolescents from distinct FA categories are obvious with regard to the year of data collection too. There were no significant differences in the odds of overweight/obesity in 2006 and 2010 in the low-FA category of adolescents, compared with 2002. However, a significant increase in the odds of their overweight/obesity was reported in 2014. In adolescents from the medium- and high-FA categories, there were significantly higher odds of overweight/obesity in all the data collection years (2006, 2010, and 2014) compared to the reference year 2002, but the odds of overweight/obesity in adolescents from the medium- and high-FA categories were somewhat lower in the last year of data collection (2014) than in 2006 and 2010 (Table 3).

Discussion

Using nationally representative data collected over the 12-year study period, we assessed the trends in overweight/obesity and the PA and ST of 11–15-year-old adolescents in relation to the material affluence of their families. The results presented here indicate complex behavioural patterns that vary across FA categories. Obviously, there are increasing differences in the prevalence of overweight/obesity when comparing low-FA and high-FA boys between 2002 and 2014. Furthermore, a more pronounced decrease in achieving 60 min of MVPA daily is seen in adolescents from the low-FA category than adolescents from the high-FA category between 2002 and 2014.

Overweight/obesity

In contrast with the economically developed countries of Western Europe and North America [32, 44], we observed an increase in the prevalence of overweight/obesity in the Czech adolescents across the FA categories between 2002 and 2014. Furthermore, it is disturbing that our findings reveal higher odds of overweight/obesity among 11-year-old adolescents than in their older peers, regardless of FA categories. In the economically developed countries of Western Europe and North America the opposite age-related pattern in terms of the prevalence of overweight/obesity generally prevails [32, 44]. The highest prevalence of overweight/obesity in low-FA girls and the highest increase in the trend-related incidence of overweight/obesity in low-FA boys might be related to unhealthy eating habits [14] and non-uniform socioeconomic development across all FA categories in low- and middle-income European countries [59, 60]. In addition, other lifestyle risk factors (smoking, alcohol consumption, cannabis use, and poor diet, especially sugar-sweetened beverages) seem to play their roles in the development of obesity in school-age children and adolescents [10, 59]. In the light of this information, it should also be noted that the Czech Republic, as the most affluent country of all of the Visegrad countries, also has the highest rate of adolescent risk behaviours (smoking, alcohol consumption, and cannabis use) [59].

Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity

Different trend-related patterns in MVPA among 11-to-15-year-old adolescents in relation to FA were found between 2002 and 2014. While in the MVPA trends gender-related differences are not apparent, MVPA trends differ according to the FA categories. Similarly to most HBSC countries [44], a decrease in daily MVPA (represented ≥60 min per day) with increasing age was also found in adolescent Czech boys and girls in 2014. In 2014, a significantly higher proportion of Czech adolescents from the highest FA category reached the MVPA recommendation and showed a lower prevalence of overweight/obesity compared with the lowest FA category. Unlike a previous study [27], we found differences in MVPA between adolescents from the low- and high-FA categories. The countries without noticeable FA-related differences in MVPA include Austria, Belgium (French), Greenland, Ireland, Malta, Portugal, the Republic of Moldova, and Romania [44].

Screen time

In line with previous studies [33, 35, 61], we found higher ST in adolescents of both genders at weekends than on weekdays, and overall higher ST in the boys than in the girls on both weekdays and weekend days. Similarly to adolescents from Canada, Iceland, Scotland, Finland, Germany, Italy, Slovenia, and Malta, girls of all ages reported less excessive ST than boys in 2014 [16, 44]. This finding probably reflects the natural higher need for face-to-face communication and social interaction in girls and the higher preference for PC gaming in boys [62]. However, unlike other studies [35, 63], the Czech adolescents from the low-FA category reported a slightly lower incidence of excessive ST (>2 h a day) than adolescents from the high-FA category both on weekdays and at weekends in all the data collection years between 2002 and 2014. This may partly be attributed to differences in rates of PC ownership between low-income households and high-income households [64]. However, further research on the topic is warranted because such a finding is rather unprecedented.

Correlates of overweight/obesity in relation to family affluence

A previous trend-related study [16] revealed that the daily achievement of 60 min of MVPA and non-excessive ST on school days reduces the likelihood of the occurrence of overweight/obesity in Czech adolescents overall. However, the study did not analyse whether or how overweight/obesity correlates fluctuate among adolescent groups according to FA. In line with other studies [11, 20], different correlates of overweight/obesity have been revealed in different FA categories of adolescents. However, the above-mentioned comprehensive studies did not analyse the potential PA and ST correlates of overweight/obesity. Because child obesity is the result of a long-term adverse impact on the energy balance [65], it sounds logical that high-risk TV behaviours (excessive daily TV viewing, having a television in children’s bedrooms, and TV viewing during meals – [66, 67]) and low PA [15, 19] are directly associated with childhood overweight/obesity. However, in our study both correlates (non-excessive ST and sufficient PA) together significantly reduce the odds of overweight/obesity only in adolescents from the high-FA category. Sufficient PA reduces the risk of overweight/obesity in adolescents from the medium category of FA regardless of excessive ST but not in adolescents from the low-FA category. A higher overall volume of PA seems to be a stronger correlate of normal body weight than sedentary behaviour, because a higher level of MVPA measured with an accelerometer (high tertile groups of minutes of MVPA) among children and adolescents was associated with better cardiometabolic risk factors (waist circumference, fasting triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol), regardless of their amount of sedentary time [68, 69]. Other relevant studies using accelerometers for PA measurement also find that higher MVPA (top versus the bottom quintiles of minutes of MVPA [70]) are strongly inversely correlated with obesity. In addition, higher levels of PA (the top versus the bottom quartiles of accelerometer counts per day) are prospectively associated with lower levels of obesity in adolescent white girls [71]. Although there are locally successful school-based PA interventions in the Czech Republic aimed at reducing overweight/obesity [72, 73], efforts to reduce the excessive body weight of schoolchildren continue to fail at the national level.

Strengths and limitations

The findings from the present trend analysis need to be considered in the light of the methods used. The same standardized sampling procedure and data collection and management in all four survey cycles are essential prerequisites for conducting comparable trend studies across families with different levels of affluence. Although the level of BMI is generally considered as applicable for the estimation of the prevalence of overweight/obesity [74], it has been documented that overweight/obese adolescents tend to perceive themselves as being of about normal body weight [75, 76]. Social desirability can potentially affect self-reported data on body weight and height, as well as data on PA and ST; however, the magnitude, direction and trend-related variations of these potential changes remain unknown. In the HBSC study adolescents are assured of confidentiality and anonymity, which could have helped minimize the effect of social desirability in the participants’ responses. The FA scale was shown to be a valid tool for classifying the families of adolescents according to their material affluence [53, 55,56,57,58], but the FA scale does not capture whether the property inquired about is family-owned or subject to a mortgage. Although the SES of families may be classified as high by the FA scale, family finances spent on a mortgage can limit the expenses associated with physically active pastimes of adolescents or the daily consumption of fruit and vegetables.

Future studies

A PA-friendly environment in the place of residence (available walking destinations and services, access to open space, e.g., parks, trails, green spaces) and school-related activity (school sports, physical education, and supervised PA) are positive correlates of PA in overweight and non-overweight children and adolescents [77,78,79], and a potential factor contributing to the lower incidence of overweight/obesity [72, 73]. Therefore, future trend studies should clarify the role of the school and residential environment in the changes over time in the prevalence of overweight/obesity and achieving the recommendations for PA and non-excessive ST.

Conclusions

Overall, FA is a strong factor determining trend-related changes in the prevalence of overweight/obesity and PA patterns among Czech adolescents between 2002 and 2014. From the public health perspective, it is alarming that an increase of more than 10 p.p. in daily excessive screen time among adolescents in the low-FA category between 2002 and 2014 is also accompanied by a decrease of more than 5 p.p. in the achievement of 60 min of MVPA daily. The highest prevalence of overweight/obesity in schoolchildren from families with low levels of affluence makes it essential to develop more balanced intervention programmes for effective mitigation of childhood overweight and obesity.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- FA:

-

Family affluence

- HBSC:

-

Health Behaviour in School-aged Children

- ICC:

-

Intra class correlation

- LR:

-

Logistic regression

- MVPA:

-

Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- PC:

-

Computer use

- Ref.:

-

Reference group

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- ST:

-

Screen time

- TV:

-

Television viewing

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Cawley J. The economics of childhood. Health Aff. 2010;29:364–71.

Finkelstein EA, Graham WCK, Malhotra R. Lifetime direct medical costs of childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2014;133:854–62.

Marques A, Matos M. Trends and correlates of overweight and obesity among adolescents from 2002 to 2010: a three-cohort study based on a representative sample of Portuguese adolescents. Am J Hum Biol. 2014;26:844–9.

Marques A, Matos M. Trends in prevalence of overweight and obesity: are Portuguese adolescents still increasing weight? Int J Public Health. 2016;61:49–56.

Morgen CS, Rockholm B, Brixval CE, Andersen CS, Andersen LG, Rasmussen M, et al. Trends in prevalence of overweight and obesity in Danish infants, children and adolescents-are we still on plateau? PLoS One. 2013;8:e69860.

Visscher TLS, Heitmann BL, Rissanen A, Lahti-Koski M, Lissner LA. Break in the obesity epidemic? Explained by biases or misinterpretation of the data? Int J Obes. 2015;39:189–98.

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, Fryar CD, Kruszon-Moran D, Kit BK, et al. Trends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States, 1988-1994 through 2013-2014. JAMA. 2016;315:2292–9.

Skinner AC, Skelton JA. Prevalence and trends in obesity and severe obesity among children in the United States, 1999-2012. JAMA. 2014;168:561–6.

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–81.

Lakshman R, Elks CE, Ong KK. Childhood obesity. Circulation. 2012;126:1170–9.

Wang Y, Lim H. The global childhood obesity epidemic and the association between socio-economic status and childhood obesity. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2012;24:176–88.

Malik VS, Pan A, Willett WC, Suger-sweetened HFB. Beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;84:274–88.

Must A, Barish EE, Bandini LG. Modifiable risk factors in relation to changes in BMI and fatness: what have we learned from prospective studies of school-aged children? Int J Obes (Lond). 2009;33:705–15.

Voráčová J, Sigmund E, Sigmundová D, Kalman M. Family affluence and the eating habits of 11- to 15-year-old Czech adolescents: HBSC 2002 and 2014. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:1034.

Boone-Heinonen J, Gordon-Larsen P, Adair LS. Obesogenic clusters: multidimensional adolescent obesity-related behaviors in the U.S. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36:217–30.

Sigmund E, Sigmundová D, Badura P, Kalman M, Hamrik Z, Pavelka J. Temporal trends in overweight and obesity, physical activity and screen time among Czech adolescents from 2002 to 2014: a national health behaviour in school-aged children study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:11848–68.

te Velde SJ, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Thorsdottir I, Rasmussen M, Hagstromer M, Klepp KI, et al. Patterns in sedentary and exercise behaviors and associations with overweight in 9-14-year=old boys and girls - a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:16.

Tremblay MS, Colley RC, Saunders TJ, Healy GN, Owen N. Physiological and health implications of a sedentary lifestyle. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2010;35:725–40.

Wilks DC, Besson H, Lindroos AK, Ekelund U. Objectively measured physical activity and obesity prevention in children, adolescents and adults: a systematic review of prospective studies. Obes Rev. 2011;12:e119–29.

Murasko JE. Socioeconomic status, height, and obesity in children. Econ Hum Biol. 2009;7:376–86.

Liu J, Kim J, Colabianchi N, Ortaglia A, Pate RR. Co-varying patterns of physical activity and sedentary behaviors and their long-term maintenance among adolescents. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7:465–74.

Nelson MC, Neumark-Stzainer D, Hannan PJ, Sirard JR, Story M. Longitudinal and secular trends in physical activity and sedentary behaviour during adolescence. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):e1627–34.

Landsberg B, Plachta-Danielzik S, Lange D, Johannsen M, Seiberl J, Müller MJ. Clustering of lifestyle factors and association with overweight in adolescents of the Kial obesity prevention study. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13:1708–15.

Ottevaere C, Huybrechts I, Benser J, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Cuenca-Garcia M, Dallonggeville J, et al. Clustering patterns of physical activity, sedentary and dietary behavior among European adolescents: the HELENA study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:328.

Drenowatz C, Eisenmann JC, Pfeiffer KA, Welk G, Heelan K, Gentile D, et al. Influence of socio-economic status on habitual physical activity and sedentary behavior in 8- to 11-year old children. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:214.

McCormack G, Hawe P, Perry R, Blackstaffe A. Associations between familial affluence and obesity risk behaviours among children. Paediatr Child Health. 2011;16:19–24.

Borraccino A, Lemma P, Iannotti RJ, Zambon A, Dalmasso P, Lazzeri G, et al. Socioeconomic effects on meeting physical activity guidelines: comparison among 32 countries. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:749–56.

Berghöfer A, Pischon T, Reinhold T, Apovian CM, Sharma AM, Willich SN. Obesity prevalence from a European perspective: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:200.

Knai C, Suhrcke M, Lobstein T. Obesity in Eastern Europe: an overview of its health and economic implications. Econ Hum Biol. 2007;4:392–408.

Webber L, Kilpi F, Marsh T, Rtveladze K, McPherson K, Brown M. Modelling obesity trends and related diseases in Eastern Europe. Obes Rev. 2012;13:744–51.

Webber L, Divajeva D, Marsh T, McPherson K, Brown M, Galea G, et al. The future burden of obesity-related diseases in the 53 WHO European-region countries and the impact of effective interventions: a modelling study. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004787.

Ahluwalia N, Dalmasso P, Rasmussen M, Lipsky L, Currie C, Haug E, et al. Trends in overweight prevalence among 11-, 13- and 15-years-olds in 25 countries in Europe, Canada and USA from 2002 to 2010. Eur J Pub Health. 2015;25(Suppl 2):28–32.

Sigmudová D, Sigmund E, Hamrik Z, Kalman M. Trends of overweight and obesity, physical activity and sedentary behaviour in Czech schoolchildren: HBSC study. Eur J Pub Health. 2014;24:210–5.

Kalman M, Inchley J, Sigmundova D, Iannotti RJ, Tynjälä JA, Hamrik Z, et al. Secular trends in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in 32 countries from 2002 to 2010: a cross-national perspective. Eur J Pub Health. 2015;25(Suppl 2):37–40.

Bucksch J, Sigmundova D, Hamrik Z, Troped PJ, Melkevik O, Ahluwalia N, et al. International trends in adolescent screen time behaviors from 2002 to 2010. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58:417–25.

Currie C, Nic Gabhainn S, Godeau E. The health behaviour in school-aged children: WHO collaborative cross-national (HBSC) study: origins, concept, history and development 1982-2008. Int J Public Health. 2009;54(Suppl 2):167–9.

Ritschelová I, Bartoňová E, Rojíček M. (eds.). Demographic Yearbook of the Czech Republic 2014. 1st ed. Prague: Czech Statistical Office; 2015. Code: 130067–15.

Growth reference data for 5–19 years. WHO Reference 2007. http://www.who.int/growthref/en. Accessed 24 May 2017.

de Onis M, Lobstein T. Defining obesity risk status in the general childhood population: which cut-offs should we use? Int J Pediatr Obes. 2010;5:458–0.

de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:660–7.

Chan NPT, Choi KC, Nelson EAS, Sung RYT, Chan JCN, Kong APS. Self-reported body weight and height: an assessment tool for identifying children with overweight/obesity status and cardiometabolic risk factors clustering. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17:282–91.

Fonseca H, Silva AM, Matos MG, Esteves I, Costa P, Guerra A, et al. Validity of BMI based on self-reported weight and height in adolescents. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:83–8.

Janssen I, LeBlanc AG. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;12:10.

Inchley J, Currie D, Young T, Samdal O, Torsheim T, Augustson L, et al. Growing up unequal: gender and socioeconomic differences in young people's health and well-being. Health Behaviour in School-Aged children (HBSC) Study: International report from the 2013/2014 survey. Health Policy for children and adolescents, No. 7. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe 2016. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/303438/HSBC-No.7-Growing-up-unequal-Full-Report.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2017.

Prochaska JJ, Sallis JF, Long BA. Physical activity screening measure for use with adolescents in primary care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:554–9.

Ridgers ND, Timperio A, Crawford D, Salmon J. Validity of a brief self-report instrument for assessing compliance with physical activity guidelines amongst adolescents. J Sci Med Sport. 2012;15:136–41.

Bobakova D, Hamrik Z, Badura P, Sigmundova D, Nalecz H, Kalman M. Test-retest reliability of selected physical activity and sedentary behavior HBSC items in the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Poland. Int J Public Health. 2015;60:59–67.

Liu Y, Wang M, Tynjälä J, Lv Y, Villberg J, Zhang Z, et al. Test–retest reliability of selected items of health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) survey questionnaire in Beijing, China. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:73.

Tremblay MS, LeBlanc AG, Kho ME, Saunders TJ, Larouche R, Colley RC, et al. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:98.

Schmitz KH, Harnack L, Fulton JE, Jacobs DR Jr, Gao S, Lytle AL, et al. Reliability and validity of a brief questionnaire to assess television viewing and computer use by middle school children. J Sch Health. 2004;74:370–7.

Vereecken CA, Todd J, Roberts C, Mulvihill C, Maes L. Television viewing behaviour and associations with food habits in different countries. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9:244–50.

Rey-López JP, Vicente-Rodriguez G, Ortega FB, Ruiz JR, Martinez-Gómez D, De Henauw S, et al. Sedentary patterns and media availability in European adolescents: the HELENA study. Prev Med. 2010;51:50–5.

Currie C, Molcho M, Boyce W, Holstein B, Torsheim T, Richter M. Researching health inequalities in adolescents: the development of the health behaviour in school-aged children (hbsc) family affluence scale. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:1429–36.

Hartley JEK, Levin K, Currie C. A new version of the HBSC family affluence scale – FAS III: Scottish qualitative findings from the international FAS development study. Child Indicat Res. 2015;9:233–45.

Andersen A, Krølner R, Currie C, Dallago L, Due P, Richter M, et al. High agreement on family affluence between children's and parents' reports: international study of 11-year-old children. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:1092–4.

Boyce W, Torsheim T, Currie C, Zambon A. The family affluence scale as a measure of national wealth: validation of an adolescent self-reported measure. Soc Indic Res. 2006;78:473–7.

Liu Y, Wang M, Villberg J, Torsheim T, Tynjälä J, Lv Y, et al. Reliability and validity of family affluence scale (FAS II) among adolescents in Beijing. China Child Indicat Res. 2012;5:235–51.

Molcho M, Gabhainn SN, Kelleher CC. Assessing the use of the family affluence scale (fas) among Irish schoolchildren. Ir Med J. 2007;100(Suppl 8):37–9.

Mazur J, Kowalewska A, Baska T, Sigmund E, Nałęcz H, Nemeth A, et al. Patterns of physical activity and multiple risk behaviour in adolescents from Visegrad countires. Zdrowie Publiczne I Zarządzanie. 2014;12:56–67.

Rockholm B, Baker JL, Sørensen TIA. The levelling off of the obesity epidemic since the year 1999 – a review of evidence and perspectives. Obes Rev. 2010;11:835–46.

Iannotti RJ, Wang J. Trends in physical activity, sedentary behavior, diet, and BMI among US adolescents, 2001–2009. Pediatrics. 2013;132:606–14.

Hartmann T, Klimmt C. Gender and computer games: exploring females' dislikes. J Comp-Med Comm. 2006;11:910–31.

Cui Z, Hardy LL, Dibley MJ, Bauman A. Temporal trends and recent correlates in sedentary behaviours in Chinese children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:93.

Czech Statistical Office. Equipping households with information and communication technologies (public database). 2017. https://vdb.czso.cz/vdbvo2/faces/cs/index.jsf?page=vystup-objekt&pvokc=&katalog=31031&pvo=ICT03&z=T. Accessed 24 May 2017.

Katzmarzyk PT, Barreira TV, Broyles ST, Champagne CM, Chaput JP, Fogelholm M, et al. The international study of childhood obesity, lifestyle and the environment (ISCOLE): design and methods. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:900.

Lissner L, Lanfer A, Gwozdz W, Olafsdottir S, Eiben G, Moreno LA, et al. Television habits in relation to overweight, diet and taste preferences in European children: the IDEFICS study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2012;27:705–15.

Pavelka J, Husarova D, Sevcikova A, Madarasova GA. Country, age and gender differences in the prevalence of screen-based behaviour and family-related factors among school-aged children. Acta Gymnica. 2016;46:143–51.

Chaput JP, Saunders TJ, Mathieu MÈ, Henderson M, Tremblay MS, O’Loughlin J, et al. Combined associations between moderate to vigorous physical activity and sedentary behaviour with cardiometabolic risk factors in children. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2013;38:477–83.

Ekelund U, Luan J, Sherar LB, Esliger DW, Griew P, Cooper A. Moderate to vigorous physical activity and sedentary time and cardiometabolic risk factors in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2012;307:704–12.

Ness AR, Leary SD, Mattocks C, Blair SN, Reilly JJ, Wells J, et al. Objectively measured physical activity and fat mass in a large cohort of children. PLoS Med. 2007;4:476–84.

White J, Jago R. Prospective associations between physical activity and obesity among adolescent girls: racial differences and implications for prevention. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:522–7.

Sigmund E, El Ansari W, Sigmundová D. Does school-based physical activity decrease overweight and obesity in children 6-9 years? A two-year non-randomized longitudinal intervention study in the Czech Republic. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:570.

Sigmund E, Sigmundová D. Longitudinal 2-year follow-up on the effect of a non-randomised school-based physical activity intervention on reducing overweight and obesity of Czech children aged 10–12 years. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10:3667–83.

Freedman DS, Sherry B. The validity of BMI as an indicator of body fatness and risk among children. Pediatrics. 2009;124(Suppl 1):23–34.

Elgar FJ, Stewart JM. Validity of self-report screening for overweight and obesity. Evidence from the Canadian community health survey. Can J Public Health. 2008;99:423–7.

Jackson SE, Johnson F, Croker H, Wardle J. Weight perceptions in a population sample of English adolescents: cause for celebration or concern. Int J Obes. 2015;39:1488–93.

Sallis JF, Bull F, Guthold R, Heath GW, Inoue S, Kelly P, et al. Progress in physical activity over the Olympic quadrennium. Lancet. 2016;388:1325–36.

Groffik D, Sigmund E, Frömel K, Chmelík F, Nováková Lokvencová P. The contribution of school breaks to the all-day physical activity of 9- and 10-year-old overweight and non-overweight children. Int J Public Health. 2012;57:711–8.

Sigmund E, Sigmundová D, Šnoblová R, Gecková AM. ActiTrainer-determined segmented moderate-to-vigorous physical activity patterns among normal-weight and overweight-to-obese Czech schoolchildren. Eur J Pediatr. 2014;173:321–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all adolescents for participation in the study. Special thanks go to the school management members who helped facilitate the research.

Funding

This study was supported a research grant from the Czech Science Foundation under reg. No. 17-12579S and the institutional grant of the Palacký University Olomouc reg. No. IGA_FTK_UP_2017_009.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author ES. The data are not publicly available due to rules of funded projects.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ES conceived the study, obtained the funding, and led manuscript writing. ES, PB, DS, JV, MK, JP, JV, VH and ZH prepared a national research protocol survey and participated in data collection. DS, ES and JZ undertook the data analysis and interpreted the results. ES and PB wrote the core of the manuscript with inputs from DS, JV, JZ, MK, JP, JV, VH and ZH. All authors interpreted, read and approved the final version of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics committee of the Faculty of Physical Culture, Palacký University, on 4th March 2016 under reg. no. 9/2016. All adolescents, teachers, and school management received detailed information on the design and purpose of the survey at a meeting at each of the participating schools. The consent to the realization of the survey was obtained through the school management at all the schools involved in the survey. Parent of the adolescent were informed about the survey, its design and content via the school management in advance and could withdraw their child if they wished. Participation of adolescents was in each cycle of data collection was voluntary and without any financial incentives. All participating schools received feedback on the overall school results after data processing.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sigmund, E., Badura, P., Sigmundová, D. et al. Trends and correlates of overweight/obesity in Czech adolescents in relation to family socioeconomic status over a 12-year study period (2002–2014). BMC Public Health 18, 122 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-5013-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-5013-1