Abstract

Background

Obesity has been recognised as an important contributing factor in the development of various diseases, but comparative data on this condition are limited. We therefore aimed to identify and discuss current epidemiological data on the prevalence of obesity in European countries.

Methods

We identified relevant published studies by means of a MEDLINE search (1990–2008) supplemented by information obtained from regulatory agencies. We only included surveys that used direct measures of weight and height and were representative of each country's overall population.

Results

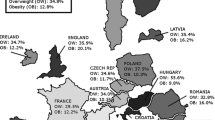

In Europe, the prevalence of obesity (body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2) in men ranged from 4.0% to 28.3% and in women from 6.2% to 36.5%. We observed considerable geographic variation, with prevalence rates in Central, Eastern, and Southern Europe being higher than those in Western and Northern Europe.

Conclusion

In Europe, obesity has reached epidemic proportions. The data presented in our review emphasise the need for effective therapeutic and preventive strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

"Let me have men around me that are fat..."

In the first act of Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, the Roman emperor suggests that higher body weight correlates with a well-balanced mental disposition. In Caesar's times, of course, obesity was not considered a medical risk factor. Since the nineteenth century, however, a high-calorie diet together with a sedentary lifestyle has been recognised as a potential risk factor for cardiovascular disease [1], cancer, and diabetes mellitus [2]. A variety of factors influence the rate of obesity in any particular region, including age patterns [3], socioeconomic factors [4], and a lack of physical activity [5]. In the medical community and at public health institutions worldwide, awareness is growing of the need to develop and implement effective treatments for obesity [6–8].

To date there have been several studies on the prevalence of obesity in Europe, most of which have involved national or regional cross-sectional surveys. There have also been international surveys, such as the WHO Multinational Monitoring of Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Diseases (MONICA) and the WHO Countrywide Integrated Noncommunicable Diseases Intervention (CINDI). However, some of these studies are based only on self-reports and may thus provide biased estimates of the prevalence of obesity in the general population. To help provide a clearer picture of the current situation, we aimed in the present study to summarise the available epidemiological data on the prevalence of obesity in European countries. We investigate the health-economic burden of obesity in a separate paper [9].

Methods

Searching

In population-based studies, overweight and obesity are frequently identified and evaluated using the body mass index (BMI), calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in metres. We used the four classes of increasing severity which the World Health Organisation has defined consistent with the notion of graded risk (BMI 18.5 – 24.9 kg/m2 = normal; 25.0 – 29.9 kg/m2 = pre-obese/overweight; ≥ 30.0 kg/m2 = obese).

For the present study, we performed a systematic MEDLINE search in February 2008 using PubMed. The search limits included the date of publication (i.e. between 1 January 1990 and the start of our MEDLINE search), the age of the subjects (18 years and older), and was limited to human studies only. The search words had to be part of the title or abstract.

For each country on the European continent, we performed a separate search using the following three keyword combinations:

1.) obes* AND country

2.) BMI AND country NOT obes* AND country

3.) adiposity AND country NOT obes* AND country NOT BMI and country

The Boolean operator "NOT" was used to exclude articles that had been found in previous searches. If the number of results for a keyword combination exceeded 200, we refined the search by adding the phrase "AND epidemiol*". We also performed a search based on the references cited in review articles. Other terms related to obesity and BMI, such as weight, excess weight, fatness, body size, etc., were not included as keywords. The risk of overlooking relevant epidemiological data was minimised, however, by scanning for cross-references and by checking review articles. In addition to our systematic PubMed search, we obtained data from the official website of the European Union http://europa.eu.int.

Selection

To be included in our review the articles had to fulfil the following criteria:

-

The age range had to be representative of the respective country's or region's adult population and at least include subjects between the ages of 25 and 65. Representativeness was assumed if the Methods section of the publication indicated that the study population had been randomly selected.

-

The studies had to use direct measurements of anthropometric data.

Validity assessment

We analysed our search results in three rounds. In the first round, we included or excluded articles based on their title. In the second round, we selected or dropped these articles after reviewing their abstracts. In the third round, we obtained the full-text version of each of the remaining articles. Two researchers assessed the publications independently. Disagreements regarding study selection or the methodological assessment of studies were resolved in discussions.

Study characteristics

We included national surveys and regional surveys. Studies that used interviews or questionnaires to obtain anthropometric data were only included if studies based on direct measures were unavailable. Studies in which the age distribution within the study population was only partially representative of the age distribution in the general adult population of the country or region in question were only included if completely representative data were not available. If several figures were reported from within the same population sample, as is possible in serial surveys, the most recent data were included. If we were unable to find any articles using the abovementioned criteria, we used data obtained from the International Association for the Study of Obesity (IASO) website [10].

Results

Using the keyword combinations and limits described above, our PubMed search returned a total of 2890 results. Ultimately, 49 articles fulfilled our inclusion criteria. Most of these were cross-sectional surveys, but some were longitudinal cohort studies that estimated the prevalence of obesity using baseline data.

The prevalence of obesity in men ranged from 4.0% to 28.3% and in women from 6.2% to 36.5% (Table 1). The highest prevalences (i.e. greater than 25%) were found in regions of Italy and Spain in both sexes [11, 12], as well as in Portugal, Poland, the Czech Republic, Romania, and Albania in women [13–17]. Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean countries showed higher prevalences of obesity than countries in Western and Northern Europe. The time span during which the surveys were conducted varied considerably, the earliest study having been performed in the late 1980s [18] and the most recent in 2005 [19].

Geographic variation in the prevalence of obesity among European countries is shown in Figure 1 for the male population and in Figure 2 for the female population.

Discussion

Data from the WHO-MONICA study revealed markedly different prevalence patterns within Europe, ranging from 7% in Swedish men to 45% in women from Lithuania [20, 21]. In the United States, prevalences comparable to those seen in Europe today were already observed in data from the NHANES III survey, conducted 15 years ago. In a recent NHANES survey, which includes data from 2004, prevalences in the US ranged from 29% in white men to 50% in black women [22]. Data from the US show that the prevalence of obesity is rising continuously, and similar trends have been reported recently for the Chinese population, in which the prevalence of obesity has doubled over the past decade [23]. With these worldwide trends in mind, and based on the data currently available for Europe, it would appear safe to assume that obesity in Europe is approaching, if it has not already reached, epidemic proportions. Naturally, it needs to be noted here that there are populations, such as the Japanese, that do not follow the worldwide trend [24].

For several countries in Europe, there are no data available that go beyond the second MONICA survey conducted in the early 1990s. Other European studies have not contributed nationally representative data based on direct measures: The EPIC cohort (European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition) for example, was conducted primarily to investigate an association between cancer and diet and only included subjects between the ages of 50 and 64 [25]. The EURALIM Project [26] aimed to determine the extent to which European data could be pooled in a common database for international comparisons and thus did not collect any new data. The Institute of European Food Studies (IEFS) reported very low prevalences, but used only self-reported obesity as its measure [27]. A series of recent studies in Sweden were based primarily on self-reported weight and height [28, 29]. As a result, we were only able to include two studies with regional samples from this series in our survey. Finally, it should be noted that the IASO's International Obesity Taskforce (IOTF) database does not routinely list references and only indicates whether data are based on self-reported weight and height. Moreover, because the IOTF database does not provide information on sample sizes or sampling methods, it is often unclear whether these data are representative.

Most of the studies included in our review were restricted to specific regions or age ranges. Thus for Albania, Austria, Croatia, Denmark, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Romania, Sweden, and Switzerland, only regional data within countries were available, in part because we had to exclude several national surveys that had been based solely on self-reported weight and height. As a result, our review may overestimate or underestimate the prevalence of obesity in these countries. France is the only country in our review for which data were only available based on self-reports. We included these data in our review because data with greater validity were not available. With regard to Spain, the regional surveys included in our study all had a sufficiently representative sample and adequate sample size. Nevertheless, the data showed large variations, which may be attributable to regional differences in living conditions and socioeconomic factors related to obesity prevalence.

Overall, in the central, eastern, and southern regions of Europe, prevalence rates are higher than in the western or northern regions. This geographic pattern can be explained, at least in part, by different socioeconomic conditions, as well as by lifestyle and nutritional factors. The prevalence of obesity in Spain and Italy, in particular, is high, and there has been recent discussion in the literature about urbanisation and the globalisation of certain lifestyle factors that have had a negative impact on the traditional Mediterranean diet [30].

Aside from dietary patterns, alterations in lifestyle have been identified as major factors contributing to the growing BMI. Data from a large European prospective cohort indicate that the intake of fatty acid fractions accounted for less that 1% of variance in BMI in Spanish subjects, whereas all dietary and non-dietary variables accounted for 21% of variance in BMI among women and 6.7% of variance in BMI among men [12]. Furthermore, an analysis of sedentary and non-sedentary leisure activities in 15 EU countries showed that obesity and overweight are strongly associated with sedentary lifestyle and a lack of physical activity [31]. These results are supported by data from the Baltic States. Approximately 50% of the participants in three national surveys conducted in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania in 1997 indicated that they did not engage in physical activity during their leisure-time [32].

The wide variations in BMI seen in different European populations may also be due in part to ethnic affiliation. In studies including various groups of immigrants in Canada [33] and Sweden [34], ethnicity has been shown to be a major determinant of obesity independently of socioeconomic factors. Many European countries have undergone substantial population changes due to immigration from Eastern Europe, as well as from outside of Europe, over the past two decades [35].

The prevalence of obesity in Europe has significantly increased over the past several decades, a phenomenon that is corroborated by data from several other industrialised countries outside Europe. In the mid-1980s, 15% of the male and 17% of the female population in Europe had a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 [36], meaning that the rate of obesity has increased by approximately 30% over the past 10 to 15 years. National surveys for example in the United Kingdom indicate that the rate of obesity there increased by approximately 15% between 1943 and 1965 [37].

The surveys included in our review were conducted within a wide time span between the mid-1980s and 2003. As a result, the prevalence data presented here were collected during different phases of an increasing trend. We are aware that the decision only to include surveys based on direct measures decreases comparability over time, because recent surveys based on questionnaires could not included in our review. Nevertheless, we felt that this limitation is outweighed by the increased precision of measurement provided by our approach.

Indeed, the underreporting of weight and height in many surveys yields far lower prevalence rates. This can be seen, for example, in the IEFS survey, which included approximately 15,000 subjects from 15 different countries in the European Union [27, 38]. Self-reports of BMI are probably optimistic compared to direct measurements made by an interviewer. Table 2 compares self-reported and directly measured data for those countries for which comparable surveys were published. Although there were considerable discrepancies in several countries, other countries showed prevalences that did not differ markedly between self-report and direct measurement. The prevalences based on self-reported data given for France are far lower than those seen in countries for which prevalence data are based on direct measures. However, because of the discrepancies described above, it would be incorrect to assume that the low prevalences seen in France are due entirely to underreporting. Clearly, life-style factors and other variables may play an important role.

Comparing self-reported BMI from the Behavioural Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) with the directly measured data from the NHANES study revealed that the former underestimated the prevalence of obesity by 9.5% [39]. A recent study validating self-reported data from Spain showed that self-reported BMI led to moderate underestimation [40].

Several recent reviews have addressed the distribution and prevalences of obesity in Europe. These publications largely confirm our findings with respect to the regional distribution of obesity prevalences, including the east-west gradient and the lower prevalences observed in the Scandinavian countries. However, the overall prevalences reported in these publications were lower than those seen in our analysis and do not reflect recent developments in the Mediterranean countries [41]. The pan-EU study of obesity [31] conducted by the Institute of European Food Studies (IEFS) included over 15,000 individuals and also showed lower prevalences in data based on self-reported obesity. Reviews that include self-reported weight and height may thus underestimate obesity prevalence.

The limited validity in self-report estimates should be taken into consideration when using these data to make decisions concerning public health recommendations.

Conclusion

In summary, although a variety of data on obesity and associated morbidity in Europe are available, there is considerable variation in the methods used by the different surveys. Improving the comparability of obesity-related prevalence data should remain a top priority in future research [42]. Moreover, developing effective and long-lasting therapeutic and preventive strategies will require acknowledging that obesity in Europe is a serious medical disorder.

References

Dusch von TK: Lehrbuch der Herzkrankheiten. 1868, Leipzig, Engelmann Verlag

Gikas A, Sotiropoulos A, Panagiotakos D, Peppas T, Skliros E, Pappas S: Prevalence, and associated risk factors, of self-reported diabetes mellitus in a sample of adult urban population in Greece: MEDICAL Exit Poll Research in Salamis (MEDICAL EXPRESS 2002). BMC Public Health. 2004, 4: 2-10.1186/1471-2458-4-2.

Bartali B, Benvenuti E, Corsi AM, Bandinelli S, Russo CR, Di IA, Lauretani F, Ferrucci L: Changes in anthropometric measures in men and women across the life-span: findings from the InCHIANTI study. Soz Praventivmed. 2002, 47: 336-348. 10.1007/PL00012644.

Heitmann BL: [Occurrence and development of overweight and obesity among adult Danes aged 30-60 years]. Ugeskr Laeger. 1999, 161: 4380-4384.

Lindstrom M, Isacsson SO, Merlo J: Increasing prevalence of overweight, obesity and physical inactivity: two population-based studies 1986 and 1994. Eur J Public Health. 2003, 13: 306-312. 10.1093/eurpub/13.4.306.

Brug J: The European charter for counteracting obesity: a late but important step towards action. Observations on the WHO-Europe ministerial conference, Istanbul, November 15-17, 2006. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2007, 4: 11-10.1186/1479-5868-4-11.

Knai C, Suhrcke M, Lobstein T: Obesity in Eastern Europe: an overview of its health and economic implications. Econ Hum Biol. 2007, 5: 392-408. 10.1016/j.ehb.2007.08.002.

James WP: The epidemiology of obesity: the size of the problem. J Intern Med. 2008, 263: 336-352. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.01922.x.

Müller-Riemenschneider F, Reinhold T, Berghöfer A, Willich SN: Health-Economic Burden of Obesity in Europe. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2008

International Association for the Study of Obesity: Global Obesity Prevalence in Adults. 2006, International Association for the Study of Obesity, [http://www.iaso.org]

Capuano V, Bambacaro A, D'Arminio T, Vecchio G, Cappuccio L: Correlation between body mass index and others risk factors for cardiovascular disease in women compared with men. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2003, 60: 295-300.

Gonzalez CA, Pera G, Quiros JR, Lasheras C, Tormo MJ, Rodriguez M, Navarro C, Martinez C, Dorronsoro M, Chirlaque MD, Beguiristain JM, Barricarte A, Amiano P, Agudo A: Types of fat intake and body mass index in a Mediterranean country. Public Health Nutr. 2000, 3: 329-336. 10.1017/S1368980000000379.

Santos AC, Barros H: Prevalence and determinants of obesity in an urban sample of Portuguese adults. Public Health. 2003, 117: 430-437. 10.1016/S0033-3506(03)00139-2.

Dennis BH, Pajak A, Pardo B, Davis CE, Williams OD, Piotrowski W: Weight gain and its correlates in Poland between 1983 and 1993. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000, 24: 1507-1513. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801435.

Skodova Z, Pisa Z, Vojtisek P, Emrova R, Pikhartova J, Hoke M, Cicha Z, Hronkova M, Berka L, Valenta Z, .: [Changes in the cardiovascular risk profile of the population of the Czech Republic--MONICA 1992]. Cas Lek Cesk. 1994, 133: 624-626.

Molarius A, Seidell JC, Kuulasmaa K, Dobson AJ, Sans S: Smoking and relative body weight: an international perspective from the WHO MONICA Project. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1997, 51: 252-260.

Shapo L, Pomerleau J, McKee M, Coker R, Ylli A: Body weight patterns in a country in transition: a population-based survey in Tirana City, Albania. Public Health Nutr. 2003, 6: 471-477. 10.1079/PHN2002451.

Smolej-Narancic N: Nutritional status of the population in Dalmatia, Croatia. Coll Antropol. 1999, 23: 59-68.

Pikhart H, Bobak M, Malyutina S, Pajak A, Kubinova R, Marmot M: Obesity and education in three countries of the Central and Eastern Europe: the HAPIEE study. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2007, 15: 140-142.

Heseker H, Hartmann S, Kubler W, Schneider R: An epidemiologic study of food consumption habits in Germany. Metabolism. 1995, 44: 10-13. 10.1016/0026-0495(95)90202-3.

Heseker H, Schmid A: [Epidemiology of obesity]. Ther Umsch. 2000, 57: 478-481. 10.1024/0040-5930.57.8.478.

Wang YC, Colditz GA, Kuntz KM: Forecasting the obesity epidemic in the aging U.S. population. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007, 15: 2855-2865.

Ding EL, Malik VS: Convergence of obesity and high glycemic diet on compounding diabetes and cardiovascular risks in modernizing China: an emerging public health dilemma. Global Health. 2008, 4: 4-10.1186/1744-8603-4-4.

Hermanussen M, Molinari L, Satake T: BMI in Japanese children since 1948: no evidence of a major rise in the prevalence of obesity in Japan. Anthropol Anz. 2007, 65: 275-283.

Haftenberger M, Lahmann PH, Panico S, Gonzalez CA, Seidell JC, Boeing H, Giurdanella MC, Krogh V, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Peeters PH, Skeie G, Hjartaker A, Rodriguez M, Quiros JR, Berglund G, Janlert U, Khaw KT, Spencer EA, Overvad K, Tjonneland A, Clavel-Chapelon F, Tehard B, Miller AB, Klipstein-Grobusch K, Benetou V, Kiriazi G, Riboli E, Slimani N: Overweight, obesity and fat distribution in 50- to 64-year-old participants in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Public Health Nutr. 2002, 5: 1147-1162.

Beer-Borst S, Morabia A, Hercberg S, Vitek O, Bernstein MS, Galan P, Galasso R, Giampaoli S, Houterman S, McCrum E, Panico S, Pannozzo F, Preziosi P, Ribas L, Serra-Majem L, Verschuren WM, Yarnell J, Northridge ME: Obesity and other health determinants across Europe: the EURALIM project. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000, 54: 424-430. 10.1136/jech.54.6.424.

Martinez JA, Kearney JM, Kafatos A, Paquet S, Martinez-Gonzalez MA: Variables independently associated with self-reported obesity in the European Union. Public Health Nutr. 1999, 2: 125-133.

Lissner L, Johansson SE, Qvist J, Rossner S, Wolk A: Social mapping of the obesity epidemic in Sweden. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000, 24: 801-805. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801237.

Sundquist K, Qvist J, Johansson SE, Sundquist J: Increasing trends of obesity in Sweden between 1996/97 and 2000/01. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004, 28: 254-261.

Belahsen R, Rguibi M: Population health and Mediterranean diet in southern Mediterranean countries. Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9: 1130-1135. 10.1017/S1368980007668517.

Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Martinez JA, Hu FB, Gibney MJ, Kearney J: Physical inactivity, sedentary lifestyle and obesity in the European Union. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999, 23: 1192-1201. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801049.

Pomerleau J, Pudule I, Grinberga D, Kadziauskiene K, Abaravicius A, Bartkeviciute R, Vaask S, Robertson A, McKee M: Patterns of body weight in the Baltic Republics. Public Health Nutr. 2000, 3: 3-10. 10.1017/S1368980000000021.

Tremblay MS, Perez CE, Ardern CI, Bryan SN, Katzmarzyk PT: Obesity, overweight and ethnicity. Health Rep. 2005, 16: 23-34.

Gadd M, Sundquist J, Johansson SE, Wandell P: Do immigrants have an increased prevalence of unhealthy behaviours and risk factors for coronary heart disease?. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2005, 12: 535-541. 10.1097/00149831-200512000-00004.

Zimmermann K: European Migration: What Do We Know?. 2005, USA, Oxford University Press

Bergmann K, Menzel R, Bergmann E, Tietze K, Stolzenberg H, Hoffmeister H: Verbreitung von Übergewicht in der erwachsenen Bevölkerung der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Akt Ernähr. 1989, 14: 205-208.

Khosla T, Lowe CR: Height and weight of British men. Lancet. 1968, 1: 742-745. 10.1016/S0140-6736(68)92183-1.

Varo JJ, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Martinez JA: [Obesity prevalence in Europe]. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2002, 25 Suppl 1: 103-108.

Yun S, Zhu BP, Black W, Brownson RC: A comparison of national estimates of obesity prevalence from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Int J Obes (Lond). 2006, 30: 164-170. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803125.

Basterra-Gortari FJ, Bes-Rastrollo M, Forga L, Martinez JA, Martinez-Gonzalez MA: [Validity of self-reported body mass index in the National Health Survey]. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2007, 30: 373-381.

Rabin BA, Boehmer TK, Brownson RC: Cross-national comparison of environmental and policy correlates of obesity in Europe. Eur J Public Health. 2007, 17: 53-61. 10.1093/eurpub/ckl073.

Aromaa A, Koponen P, Tafforeau J, Vermeire C: Evaluation of Health Interview Surveys and Health Examination Surveys in the European Union. Eur J Public Health. 2003, 13: 67-72. 10.1093/eurpub/13.suppl_1.67.

Ulmer H, Diem G, Bischof HP, Ruttmann E, Concin H: Recent trends and sociodemographic distribution of cardiovascular risk factors: results from two population surveys in the Austrian WHO CINDI demonstration area. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2001, 113: 573-579.

S. DH, D. DB, P. S, Kornitzer M, G. DB: Trends and regional differences in coronary risk factors in two areas in Belgium: final results from the MONICA Ghent-Charleroi Study. J Cardiovasc Risk. 2000, 7: 347-357.

Hlubik P, Opltova L, Chaloupka J: [Prevalence of obesity in selected subpopulations in the Czech Republic]. Sb Lek. 2000, 101: 59-65.

Heitmann BL: Ten-year trends in overweight and obesity among Danish men and women aged 30-60 years. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000, 24: 1347-1352. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801388.

Frost L, Hune LJ, Vestergaard P: Overweight and obesity as risk factors for atrial fibrillation or flutter: the Danish Diet, Cancer, and Health Study. Am J Med. 2005, 118: 489-495. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.031.

Heitmann BL, Stroger U, Mikkelsen KL, Holst C, Sorensen TI: Large heterogeneity of the obesity epidemic in Danish adults. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7: 453-460. 10.1079/PHN2003542.

Klumbiene J, Petkeviciene J, Helasoja V, Prattala R, Kasmel A: Sociodemographic and health behaviour factors associated with obesity in adult populations in Estonia, Finland and Lithuania. Eur J Public Health. 2004, 14: 390-394. 10.1093/eurpub/14.4.390.

Lahti-Koski M, Jousilahti P, Pietinen P: Secular trends in body mass index by birth cohort in eastern Finland from 1972 to 1997. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001, 25: 727-734. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801588.

Hu G, Barengo NC, Tuomilehto J, Lakka TA, Nissinen A, Jousilahti P: Relationship of physical activity and body mass index to the risk of hypertension: a prospective study in Finland. Hypertension. 2004, 43: 25-30. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107400.72456.19.

ObEpi: Résultats de l'enquete ObEpi 2003 sur l'obésité et le surpoids en France. 2003, Roche

Scali J, Siari S, Grosclaude P, Gerber M: Dietary and socio-economic factors associated with overweight and obesity in a southern French population. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7: 513-522. 10.1079/PHN2003569.

Maillard G, Charles MA, Thibult N, Forhan A, Sermet C, Basdevant A, Eschwege E: Trends in the prevalence of obesity in the French adult population between 1980 and 1991. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999, 23: 389-394. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800831.

Thefeld W: Verbreitung der Herz-Kreislauf-Risikofaktoren Hypercholesterinämie, Übergewicht, Hypertonie und Rauchen in der Bevölkerung. Bundesgesundheitsbl Gesundheitsforsch Gesundheitsschutz. 2000, Springer, 43: 415-423. 10.1007/s001030070047.

Liese AD, Doring A, Hense HW, Keil U: Five year changes in waist circumference, body mass index and obesity in Augsburg, Germany. Eur J Nutr. 2001, 40: 282-288. 10.1007/s394-001-8357-0.

Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Chrysohoou C, Risvas G, Kontogianni MD, Zampelas A, Stefanadis C: Epidemiology of overweight and obesity in a Greek adult population: the ATTICA Study. Obes Res. 2004, 12: 1914-1920.

Panagiotakos DB, Chrysohoou C, Pitsavos C, Stefanadis C: Association between the prevalence of obesity and adherence to the Mediterranean diet: the ATTICA study. Nutrition. 2006, 22: 449-456. 10.1016/j.nut.2005.11.004.

Manios Y, Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Polychronopoulos E, Stefanadis C: Implication of socio-economic status on the prevalence of overweight and obesity in Greek adults: the ATTICA study. Health Policy. 2005, 74: 224-232. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.01.014.

Pitsavos C, Panagiotakos DB, Chrysohoou C, Stefanadis C: Epidemiology of cardiovascular risk factors in Greece: aims, design and baseline characteristics of the ATTICA study. BMC Public Health. 2003, 3: 32-10.1186/1471-2458-3-32.

Allicance IUN: North/South Ireland food consumption survey. 2001, [http://www.iuna.net]

McCarthy SN, Gibney MJ, Flynn A: Overweight, obesity and physical activity levels in Irish adults: evidence from the North/South Ireland food consumption survey. Proc Nutr Soc. 2002, 61: 3-7.

Shelley E, Daly L, Collins C, Christie M, Conroy R, Gibney M, Hickey N, Kelleher C, Kilcoyne D, Lee P, .: Cardiovascular risk factor changes in the Kilkenny Health Project. A community health promotion programme. Eur Heart J. 1995, 16: 752-760.

Colucciello M, Tenconi MT, Rabagliati C, Piazza M, Orlandi M, Cornalba C: [Prevalence of risk factors for ischemic heart disease in a northern Italian adult population]. Ann Ig. 2006, 18: 23-30.

Visscher TL, Seidell JC: Time trends (1993-1997) and seasonal variation in body mass index and waist circumference in the Netherlands. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004, 28: 1309-1316. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802761.

Visscher TL, Kromhout D, Seidell JC: Long-term and recent time trends in the prevalence of obesity among Dutch men and women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002, 26: 1218-1224. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802016.

Kamycheva E, Sundsfjord J, Jorde R: Serum parathyroid hormone level is associated with body mass index. The 5th Tromso study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004, 151: 167-172. 10.1530/eje.0.1510167.

Zaletel-Kragelj L, Erzen I, Fras Z: Interregional differences in health in Slovenia. I. Estimated prevalence of selected cardiovascular and related diseases. Croat Med J. 2004, 45: 637-643.

Soriguer F, Rojo-Martinez G, Esteva A, Ruiz de Adana MS, Catala M, Merelo MJ, Beltran M, Tinahones FJ: Prevalence of obesity in south-east Spain and its relation with social and health factors. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004, 19: 33-40. 10.1023/B:EJEP.0000013254.93980.97.

Aranceta J, Perez RC, Serra ML, Ribas BL, Quiles IJ, Vioque J, Tur MJ, Mataix VJ, Llopis GJ, Tojo R, Foz SM: [Prevalence of obesity in Spain: results of the SEEDO 2000 study]. Med Clin (Barc ). 2003, 120: 608-612. 10.1157/13046926.

Aranceta J, Perez-Rodrigo C, Serra-Majem L, Ribas L, Quiles-Izquierdo J, Vioque J, Foz M: Influence of sociodemographic factors in the prevalence of obesity in Spain. The SEEDO'97 Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2001, 55: 430-435. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601189.

Schroder H, Marrugat J, Vila J, Covas MI, Elosua R: Adherence to the traditional mediterranean diet is inversely associated with body mass index and obesity in a spanish population. J Nutr. 2004, 134: 3355-3361.

Mataix J, Lopez-Frias M, Martinez-de-Victoria E, Lopez-Jurado M, Aranda P, Llopis J: Factors associated with obesity in an adult Mediterranean population: influence on plasma lipid profile. J Am Coll Nutr. 2005, 24: 456-465.

Plans P, Serra L, Castells C, Lloveras G, Pardell H, Salleras L: [Epidemiology of obesity among the adult population of Catalonia]. An Med Interna. 1992, 9: 478-482.

Berg C, Rosengren A, Aires N, Lappas G, Toren K, Thelle D, Lissner L: Trends in overweight and obesity from 1985 to 2002 in Goteborg, West Sweden. Int J Obes (Lond). 2005, 29: 916-924. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802964.

Eliasson M, Lindahl B, Lundberg V, Stegmayr B: Diabetes and obesity in Northern Sweden: occurrence and risk factors for stroke and myocardial infarction. Scand J Public Health Suppl. 2003, 61: 70-77. 10.1080/14034950310001360.

Addor V, Wietlisbach V, Narring F, Michaud PA: Cardiovascular risk factor profiles and their social gradient from adolescence to age 74 in a Swiss region. Prev Med. 2003, 36: 217-228. 10.1016/S0091-7435(02)00016-6.

Morabia A, Costanza MC: The obesity epidemic as harbinger of a metabolic disorder epidemic: trends in overweight, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes treatment in Geneva, Switzerland, 1993-2003. Am J Public Health. 2005, 95: 632-635. 10.2105/2004.047877.

Unit JHS: Risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Health Survey for England. 2003, national statistics, 2:

Bendixen H, Holst C, Sorensen TI, Raben A, Bartels EM, Astrup A: Major increase in prevalence of overweight and obesity between 1987 and 2001 among Danish adults. Obes Res. 2004, 12: 1464-1472.

Sarlio-Lahteenkorva S, Lahelma E: The association of body mass index with social and economic disadvantage in women and men. Int J Epidemiol. 1999, 28: 445-449. 10.1093/ije/28.3.445.

Heineck G: Height and weight in Germany, evidence from the German Socio-Economic Panel, 2002. Econ Hum Biol. 2006, 4: 359-382. 10.1016/j.ehb.2006.05.001.

Pagano R, La VC: Overweight and obesity in Italy, 1990-91. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1994, 18: 665-669.

Grabauskas V, Petkeviciene J, Klumbiene J, Vaisvalavicius V: The prevalence of overweight and obesity in relation to social and behavioral factors (Lithuanian health behavior monitoring). Medicina (Kaunas ). 2003, 39: 1223-1230.

van DL, Otters HB, Schuit AJ: Moderately overweight and obese patients in general practice: a population based survey. BMC Fam Pract. 2006, 7: 43-10.1186/1471-2296-7-43.

Marques-Vidal P, Dias CM: Trends in overweight and obesity in Portugal: the National Health Surveys 1995-6 and 1998-9. Obes Res. 2005, 13: 1141-1145.

Gutierrez-Fisac JL, Guallar-Castillon P, ez-Ganan L, Lopez GE, Banegas B, Rodriguez AF: Work-related physical activity is not associated with body mass index and obesity. Obes Res. 2002, 10: 270-276.

Eichholzer M, Camenzind E: [Overweight, obesity and underweigh in Switzerland: results of the 2000 Nutri-Trend Study]. Schweiz Rundsch Med Prax. 2003, 92: 847-858.

Thane CW, Bolton-Smith C, Coward WA: Comparative dietary intake and sources of phylloquinone (vitamin K1) among British adults in 1986-7 and 2000-1. Br J Nutr. 2006, 96: 1105-1115. 10.1017/BJN20061971.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/8/200/prepub

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Matthew Gaskins for editing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

AB drafted the manuscript, TP has made substantial contributions to conception of the manuscript and interpretation of data, TR has made substantial contributions to acquisition of data and analysis, CMA and AMS have been involved in critically revising the manuscript and SNW participated in the study design and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Berghöfer, A., Pischon, T., Reinhold, T. et al. Obesity prevalence from a European perspective: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 8, 200 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-200

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-200