Abstract

Background

Cycloplegics have been reported to induce changes in the lens thickness. However, the studies of correlation between cycloplegia and the lens position are limited. This study aims to investigate changes in crystalline lens rise (CLR) and other anterior segment parameters after inducing cycloplegia with tropicamide.

Methods

In this consecutive case study, 39 children (20 boys and 19 girls; mean age, 9.51 ± 1.75 years, mean spherical equivalence [SE], − 1.9 ± 1.5 D) with low-to moderate myopia were examined using CASIA 2 both before and after 30 min of administering 5-cycles (each 5 min apart) of 0.5% tropicamide. Measurements included CLR, crystalline lens thickness (CLT), mean radius of curvature of the anterior/posterior surface of the lens (Rf_ave/Rb_ave), anterior chamber depth (ACD), anterior chamber width (ACW), and central corneal thickness (CCT). Correlations of CLT and CLR with ACD, SE, and age were assessed respectively.

Results

CLT and CLR decreased significantly after cycloplegia (p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively); whereas CCT, ACD, and Rf_ave increased (p = 0.008, p < 0.001, p < 0.001, respectively). A positive correlation was found between CLR and SE (r = 0.565, p < 0.001). However, a negative correlation between ACD and CLR was found before and after cycloplegia (r = − 0.430, p = 0.006; r = − 0.342, p = 0.035, respectively).

Conclusions

The crystalline lens appeared thinner and moved backward after cycloplegia. ACD increased mainly due to the backward movement of the crystalline lens. These results aid in elucidating the impact of crystalline lens changes during the process of accommodation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The global prevalence of myopia increased to 28.3% in 2010 and is estimated to be 49.8% by 2050 with this trend [1]. This prevalence is rising in children as well, making myopia an important health concern for children worldwide [2,3,4,5]. Evidence has shown that anterior chamber changes occur along with axial length growth in myopic children’s eyes [6,7,8]. But cycloplegics, agents for paralyzing the ciliary muscle, have been reported to induce changes in the anterior segment and crystalline lens to overcome the myopic shift [9,10,11].

Cycloplegic agents, namely tropicamide, cyclopentolate, and atropine, are generally applied in ocular examinations and for myopia control [12,13,14]. Among these, tropicamide is widely used owing to its short duration of action and less side effects. Previous reports have investigated changes in the anterior chamber depth (ACD) and central corneal thickness (CCT) after cycloplegia [15,16,17,18,19]. However, the study of the correlation between cycloplegia and the crystalline lens rise (CLR), the distance between the anterior surface of the crystalline lens and the line of angle recess, had been very difficult until CASIA2 (CASIA2, TOMEY, Nagoya, Japan) was introduced.

CASIA2 is an anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) which can scan the anterior segment at a depth of 13 mm. Therefore, it can offer an opportunity to investigate the changes in the crystalline lens and anterior segment more comprehensively and aid to understand eye biometrics in myopic children better. According to our knowledge, ours is the first study to observe changes in CLR using CASIA2 after inducing cycloplegia.

Methods

Patients

This prospective, consecutive case study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai EENT Hospital and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (Approval Number: 2016037) in November 2018. Children (age, < 15 years) with low to moderate myopia were eligible for this study. Sample size was determined as 20 via the following formula: \( n=\frac{{\left({Z}_{\alpha /2}+{Z}_{\beta}\right)}^2\ast {\sigma}^2}{\delta^2} \), where the power was set to 90% and the alpha error was 0.05. Exclusion criteria were as follows: active eye pathology or systemic diseases with eye involvement, history of eye surgery, uveitis, glaucoma, and cataract and incomplete examinations due to lack of cooperation. A signed informed consent has been obtained from each patient before the study.

Examination procedure

AS-OCT examinations were performed using CASIA2, (TOMEY, Nagoya, Japan), an automatic and non-invasive device. Patients were asked to take a proper position and fixed on the red target inside the machine. The operator aligned the corneal apex and the distance until a blue cross appeared on the image. Then, patients were instructed to blink twice and open the eyes wider. After pressing the Capture button, the instrument automatically produced 16 tomographic images from 32 directions for lens biometry.

Post-cycloplegia examination was performed 30 min after administering 5 cycles (each cycle 5 min apart) of 0.5% tropicamide, which is in agreement with previous research [11]. To maintain accuracy, all examinations were done three times by the same ophthalmologist. Measurements included CLR, crystalline lens thickness (CLT), mean radius of curvature of the anterior/posterior surface of the lens (Rf_ave/ Rb_ave), ACD, anterior chamber width (ACW), and CCT. The results of manifest refraction would be used to calculate the spherical equivalent (SE).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed by SPSS software (Version.25.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics are expressed as mean ± SD. Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test the normal distribution. All measurements obtained before and after cycloplegia induction were compared using the paired t test or Wilcoxon test. Pearson’s linear correlation was used to determine the relationship between ACD and CLR, post-cycloplegia SE and among post-cycloplegia CLT and CLR. A p value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

This study included 39 eyes of 39 patients, among which 20 (51.3%) were male and 19 (48.7%) were female. The mean age was 9.51 ± 1.75 years old (range, 6–13 years). The SE ranged from − 0.25 D to − 5.75 D, and the mean SE was − 1.9 ± 1.5 D.

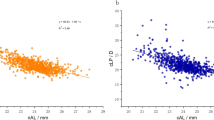

All measurements before and after tropicamide application are listed in Table 1. After cycloplegia, CCT, ACD, and Rf_ave increased 1.44 ± 3.20 μm (p = 0.008), 0.07 ± 0.05 mm (p < 0.001) and 1.00 ± 0.40 μm (p < 0.001), respectively. However, post-cycloplegia CLT and CLR decreased and the decrements were − 0.03 ± 0.03 mm (p < 0.001) and − 58.55 ± 82.92 μm (p < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 1). No significant change was noted in the measurements of ACW and Rf_ave (p = 0.122 and p = 0.169). A negative correlation was found between ACD and CLR both before and after cycloplegia (r = − 0.430, p = 0.006 and r = − 0.342, p = 0.035, respectively; Fig. 2).

Correlations between post-cycloplegia CLT, CLR, and SE

Pearson’s linear regression was used to determine the possible relationship. A positive correlation was found between CLR and SE (r = 0.565, p < 0.001; Fig. 3), whereas no correlation was found between CLT and SE (r = 0.124, p = 0.453). In addition, no relationship was found among CLT, CLR and age.

Discussion

How anterior segment and crystalline lens change after cycloplegia in low to moderate myopic children is well worth discussing. In addition to CLR, this work also investigated into several other anterior segment parameters including ACD, ACW, and mean radius of curvature of the anterior/posterior surface of the lens.

ACD increased significantly (p < 0.001) after cycloplegia in the current study. The increase in ACD was 0.07 mm, which lies in the established range of 0.18 mm to 0.06 mm [11, 16, 20, 21]. Additionally, a negative correlation was found between ACD and CLR both before and after cycloplegia (r = − 0.433, p = 0.006 and r = − 0.339, p = 0.038, respectively), indicating an association between ACD and CLR. According to the results of this study, a 58.55 μm decrease in CLR is mostly due to the change in lens position, and only attributes 0.015 mm (1/2 change in CLT) to lens thinning. Therefore, the increase in ACD would be mainly due to the backward movement of the crystalline lens. ACW was considered to be stable after cycloplegia. To our knowledge, few studies have described changes in ACW with accommodation. Du’s study [22] demonstrated that ACW did not change during maximal accommodation in healthy eyes. Chen also found no significant change in ACW in intraocular lenses eyes [23]. These results are in agreement with ours. However, the present study focuses only on the width from nasal to temporal quadrants, whereas changes in vertical ACW still needs further investigation.

The morphology changes in the lens after cycloplegia, including thinning of thickness, backward movement, and flattening of the anterior surface, were observed significantly in our study. These changes occur due to ciliary muscle relaxation and are in agreement with the most widely accepted accommodation theory proposed by Helmholz [24]. CLR, the distance between lens anterior surface and the line of angle recess, is an important parameter representing the lens positon on the vertical line. The mean (±SD) of post-cycloplegia CLR was − 135.82 ± 139.1 μm. Here, the large SD may indicate large differences in CLR at individual level. A few previous studies have been conducted on changes in lens in myopic children and few have mentioned lens position or CLR [11, 25]. The decrease in CLR with accommodation is in agreement with results reported by Yan et al. [25] and Baikoff et al. [26] Furthermore, CLR was found to have a positive correlation with SE (r = 0.537, p = 0.001), which indicated a deeper lens position in a more myopic eye. One explanation to this is that a deep lens position before myopia onset can result in hyperopic defocus, contributing to myopia progression. Experiments have demonstrated that negative lenses induce myopia through hyperopic defocus in chicken and pig models [27, 28]. Another explanation is that the crystalline lens may move backwards gradually with myopia progression. Several long-term observations on myopic children have described the increase in ACD [6,7,8]. Since axial length growth is commonly observed in myopic progression [29, 30], is there an opportunity for a crystalline lens to move backwards with adaptation to axial length growth? This question is well worth investigating in the future.

Rf_ave, which has been mentioned before, showed that the anterior surface of the crystalline lens became flatter after cycloplegia. Although Rb_ave value showed no significant change (p = 0.169), the 0.08-mm mean shift in Rb_ave indicated that the posterior surface was steeper after cycloplegia on average. In Pablo’s investigation on accommodation, anterior and posterior surface changed at rates of 0.78 ± 0.18 mm and 0.13 ± 0.07 mm per D, respectively [31]. In addition, Sun also observed a steeper change in anterior surface compared with the posterior surface with accommodation [32]. These literatures indicated that the change in refractive power of the crystalline lens was mainly attributed to the anterior surface. Here in this study, the refractive error difference was considerably smaller compared with the vergence performed in above studies on accommodation; hence, posterior surface change should be minor and more difficult to be observed. In this case, the change in Rb_ave after tropicamide cycloplegia still warrants further precise measurement.

Our study has limitations. Firstly, this was a cross-sectional observation study and further long-term studies are required to prove our data. Secondly, the sample size of this study was small. Thirdly, these study did not include a control group of normal or high myopic children. Hence, our findings may be limited to low-to-moderate myopia.

Conclusions

The crystalline lens appears thinner and moves backward after cycloplegia induction. Increase in ACD is mainly due to the backward movement of the crystalline lens. Our attempt to study these parameters with CASIA2 is new and advantageous for elucidating changes in crystalline lens with accommodation. In addition, these results are useful for physicians to read pediatric eye biometrics.

Availability of data and materials

Data and materials are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- CLR:

-

Crystalline lens rise

- CLT:

-

Crystalline lens thickness

- Rf_ave:

-

Rb_ave

Mean radius of curvature of the anterior/posterior surface of the lens

- ACD:

-

Anterior chamber depth

- ACW:

-

Anterior chamber width

- CCT:

-

Central corneal thickness

- SE:

-

Spherical equivalent

References

Holden BA, Fricke TR, Wilson DA, et al. Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:1036–42.

Edwards MH, Lam CS. The epidemiology of myopia in Hong Kong. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2004;33:34–8.

Lin LL, Shih YF, Hsiao CK, Chen CJ, Lee LA, Hung PT. Epidemiologic study of the prevalence and severity of myopia among schoolchildren in Taiwan in 2000. J Formos Med Assoc. 2001;100:684–91.

He M, Huang W, Zheng Y, et al. Refractive error and visual impairment in school children in rural southern China. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:374–82.

Pan CW, Zheng YF, Anuar AR, et al. Prevalence of refractive errors in a multiethnic Asian population: the Singapore epidemiology of eye disease study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:2590–8.

Wong HB, Machin D, Tan SB, et al. Ocular component growth curves among singaporean children with different refractive error status. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:1341–7.

Jones LA, Mitchell GL, Mutti DO, et al. Comparison of ocular component growth curves among refractive error groups in children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2317–27.

He JC. A model of the effect of lens development on refraction in schoolchildren. Optom Vis Sci. 2017;94:1129–37.

Cheng HC, Hsieh YT. Short-term refractive change and ocular parameter changes after cycloplegia. Optom Vis Sci. 2014;91:1113–7.

Raina UK, Gupta SK, Gupta A, Goray A, Saini V. Effect of cycloplegia on optical biometry in pediatric eyes. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2018;55:260–5.

Yuan Y, Zhang Z, Zhu J, et al. Responses of the ocular anterior segment and refraction to 0.5% tropicamide in Chinese school-aged children of myopia, emmetropia, and hyperopia. J Ophthalmol. 2015;2015:612728.

Fotedar R, Rochtchina E, Morgan I, Wang JJ, Mitchell P, Rose KA. Necessity of cycloplegia for assessing refractive error in 12-year-old children: a population-based study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:307–9.

Lee D. Current methods of myopia control. J Behav Optom. 2009;20:87–93.

Wolffsohn JS, Calossi A, Cho P, Gifford K, Zvirgzdina M. Global trends in myopia management attitudes and strategies in clinical practice. Con Lens Anterior Eye. 2016;39:106–16.

Chang SW, Lo AY, Su PF. Anterior segment biometry changes with cycloplegia in myopic adults. Optom Vis Sci. 2016;93:12–8.

Palamar M, Egrilmez S, Uretmen O, Yagci A, Kose S. Influences of cyclopentolate hydrochloride on anterior segment parameters with Pentacam in children. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89:e461–5.

Bagheri A, Feizi M, Shafii A, Faramarzi A, Tavakoli M, Yazdani S. Effect of cycloplegia on corneal biometrics and refractive state. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2018;13:101–9.

Huang RY, Lam AK. The effect of mydriasis from phenylephrine on corneal shape. Clin Exp Optom. 2007;90:44–8.

Saitoh K, Yoshida K, Hamatsu Y, Tazawa Y. Changes in the shape of the anterior and posterior corneal surfaces caused by mydriasis and miosis: detailed analysis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30:1024–30.

Güler E, Güragaç FB, Tenlik A, Yagci R, Arslanyilmaz Z, Balci M. Influences of topical cyclopentolate on anterior chamber parameters with a dual-Scheimpflug analyzer in healthy children. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2015;52:26–30.

Niyaz L, Can E, Seymen Z, Eraydin B. Comparison of anterior segment parameters obtained by dual-Scheimpflug analyzer before and after cycloplegia in children. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2016;53:234–7.

Du C, Shen M, Li M, Zhu D, Wang MR, Wang J. Anterior segment biometry during accommodation imaged with ultra-long scan depth optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2479–85.

Chen Q, Leng L, Shen M, Wang J, Lu F, Chen D. Biometrical measurements for the anterior segment dimensions of the eye with an intraocular lens during accommodation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:2986.

Charman WN. The eye in focus: accommodation and presbyopia. Clin Exp Optom. 2008;91:207–25.

Yan PS, Lin HT, Wang QL, Zhang ZP. Anterior segment variations with age and accommodation demonstrated by slit-lamp-adapted optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:2301–7.

Baikoff G, Lutun E, Ferraz C, Wei J. Static and dynamic analysis of the anterior segment with optical coherence tomography. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30:1843–50.

Wildsoet C, Wallman J. Choroidal and scleral mechanisms of compensation for spectacle lenses in chicks. Vis Res. 1995;35:1175–94.

Howlett MH, McFadden SA. Spectacle lens compensation in the pigmented Guinea pig. Vis Res. 2009;49:219–27.

Mutti DO, Mitchell GL, Sinnott LT, et al. Corneal and crystalline lens dimensions before and after myopia onset. Optom Vis Sci. 2012;89:251–62.

Saw SM, Chua WH, Gazzard G, Koh D, Tan DT, Stone RA. Eye growth changes in myopic children in Singapore. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:1489–94.

Pérez-Merino P, Velasco-Ocana M, Martinez-Enriquez E, Marcos S. OCT-based crystalline lens topography in accommodating eyes. Biomed Opt Express. 2015;6:5039–54.

Sun Y, Fan S, Zheng H, Dai C, Ren Q, Zhou C. Noninvasive imaging and measurement of accommodation using dual-channel SD-OCT. Curr Eye Res. 2014;39:611–9.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81570879 and 81770955; receiver XTZ): contributing to design and correction of the study; Shanghai Science and Technology Development Foundation (Grant No .17411950200 and 17411950201; receiver XTZ): supporting the interpretation of the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Designed the Experiments Concept: ZYC XTZ. Performed the experiments: TL ZYC. Analyzed the data: MYL TL. Contributed materials: YX. Wrote the paper: ZYC YX XTZ. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has been approved by the ethics committee of Eye and ENT Hospital of Fudan University, with informed consent obtained from each patient (signed by both patients and one parent of them).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest and have no proprietary interest in any of the materials mentioned in this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Z., Li, T., Li, M. et al. Effect of Tropicamide on crystalline Lens rise in low-to-moderate myopic eyes. BMC Ophthalmol 20, 327 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-020-01594-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-020-01594-8