Abstract

Background

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy encountered during pregnancy. However, the burden of pregnancy-associated breast cancer (PABC) and subsequent care is understudied in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Here, we describe the characteristics, diagnostic delays and treatment of women with PABC seeking care at a rural cancer referral facility in Rwanda.

Methods

Data from female patients aged 18–50 years with pathologically confirmed breast cancer who presented for treatment between July 1, 2012 and February 28, 2014 were retrospectively reviewed. PABC was defined as breast cancer diagnosed in a woman who was pregnant or breastfeeding. Numbers and frequencies are reported for demographic and diagnostic delay variables and Wilcoxon rank sum and Fisher’s exact tests are used to compare characteristics of women with PABC to women with non-PABC at the alpha = 0.05 significance level. Treatment and outcomes are described for women with PABC only.

Results

Of the 117 women with breast cancer, 12 (10.3%) had PABC based on medical record review. The only significant demographic differences were that women with PABC were younger (p = 0.006) and more likely to be married (p = 0.035) compared to women with non-PABC. There were no significant differences in diagnostic delays or stage at diagnosis between women with PABC and women with non-PABC women. Eleven of the women with PABC received treatment, three had documented treatment delays or modifications due to their pregnancy or breastfeeding, and four stopped breastfeeding to initiate treatment. At the end of the study period, six patients were alive, three were deceased and three patients were lost to follow-up.

Conclusions

PABC was relatively common in our cohort but may have been underreported. Although patients with PABC did not experience greater diagnostic delays, most had treatment modifications, emphasizing the potential value of PABC-specific treatment protocols in SSA. Larger prospective studies of PABC are needed to better understand particular challenges faced by these patients and inform policies and practices to optimize care for women with PABC in Rwanda and similar settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Breast cancer is the most common type of malignancy encountered during pregnancy [1,2,3,4,5]. Despite the growing body of literature on pregnancy-associated breast cancer (PABC), most often defined as breast cancer diagnosed during a pregnancy or within one to two years after delivery with some definitions extending up to five years after delivery [6], the implications of PABC remain poorly understood. Reports on prevalence, optimal management, prognosis and survival of women with PABC versus women with non-PABC are conflicting and this has had repercussions for how PABC is managed [7,8,9,10,11,12]. While at one time considered to be untreatable, recent reports suggest that mothers and babies can do well following treatment during pregnancy if it is delivered in a timely manner [5, 7]. For operable disease, surgery is considered the best treatment during pregnancy and chemotherapy can be safely delivered in the second and third trimesters [2, 8, 13,14,15,16].

Breast cancer is a growing public health concern in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), where both breast cancer incidence and mortality rates are rising [17,18,19,20]. Women with breast cancer in SSA are more likely to die of their disease than women with breast cancer in high-income regions in part because of delays in diagnosis leading to advanced stages at presentation [21]. It is likely that the relative burden of PABC is higher in SSA than in North America and Europe because of the region’s higher fertility rates, younger population, and younger median age at breast cancer diagnosis [22,23,24,25]. Women with PABC in SSA may face even longer delays to diagnosis and treatment than their counterparts with non-PABC because of low levels of breast cancer awareness, the possibility of breast cancers being misidentified as normal breast modifications that occur during pregnancy or lactation, providers delaying diagnostic workup until after pregnancy or lactation is complete, the competing priorities of pregnant women or new mothers, and the lack of alternatives to breastfeeding which make it difficult for a mother if she is advised to stop for treatment [9, 26,27,28,29,30,31]. However, despite the likely higher burden of PABC in SSA and the additional challenges women with PABC face, little is known about prevalence, presentation and management of PABC in the region [7, 8, 17, 24, 27].

Rwanda is a small low-income country in East Africa with one of the highest population densities in the continent. Breast cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed in women at national referral hospitals and is the most common adult cancer encountered at the Butaro Cancer Center of Excellence (BCCOE), a specialized cancer facility in the rural northwest [32,33,34,35,36]. Women at BCCOE often present with late stage disease and both patient and system delays are associated with later stage at presentation [21]. In this study, we focus on women with PABC seeking care at BCCOE to better understand their current demographic and clinical characteristics, diagnostic delays, how they are treated and their outcomes at the end of the study period to inform the provision of care for patients with PABC in LMICs.

Methods

Study design and setting

This retrospective cohort study included women with breast cancer presenting for treatment at BCCOE. BCCOE was opened by the Rwanda Ministry of Health in July 2012, with the support of the organizations Partners In Health, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, USA [33]. Patients are referred to BCCOE from across Rwanda and adjacent countries because of the availability and affordability of pathology services, chemotherapy, surgery and clinicians with training in cancer care. As there are no full-time oncologists at BCCOE [37], cancer treatment is facilitated through the implementation of nationally-endorsed protocols based on international standards [33,34,35,36]. Medical oncology care is provided by a team of general physicians, internists, pediatricians and nurses who follow the protocols and consult regularly with international oncology specialists. Surgical care is provided by general surgeons. As of July 2017, there was no radiation available in Rwanda.

The existing breast cancer treatment protocols provide simplified algorithms for early stage, locally advanced and metastatic disease. Since there are no specific guidelines for women with PABC, treatment follows general breast cancer protocols but can be modified based on clinician judgment, with expert consultation available from one of the partnering institutions.

Study population and data collection

The study population included female patients with pathologically confirmed breast cancer who presented at BCCOE between July 1, 2012 and February 28, 2014. Only women between 18 and 50 years old were included in the analysis to allow us to focus on the experiences of women of reproductive age and to increase the comparability of women with PABC to women with non-PABC. Clinical data were extracted from an existing database. This database included information from the medical records, such as cancer diagnosis and staging information, for all BCCOE patients who presented with a breast complaint during the study period. Staging of breast cancer patients at BCCOE was conducted according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system [38], but treatment protocols were based on whether patients fell into simplified categories of “early,” “locally advanced,” or “metastatic” disease. In Table 1 patients are grouped as having non-metastatic and metastatic disease to increase power to explore differences in these two groups. A focused chart review of all patients meeting the study criteria was conducted to confirm who had PABC. For our purposes, PABC was defined as breast cancer diagnosed during pregnancy or when a woman was breastfeeding. Breastfeeding was included within our definition because the date of last delivery was not always documented in cancer patients’ medical records, making it impossible to calculate the precise length of time since delivery. Since the median duration of breastfeeding in Rwanda is approximately 2.5 years [36, 39], we deemed it reasonable to use breastfeeding as a proxy for being within two to three years postpartum [6]. Any patients that met our definition were classified as having PABC, and data on their treatment and outcomes was collected.

For the focused chart review, a data collection form designed by the research team included a series of yes/no questions to prompt the data collector to record treatment information and to note any indications of treatment delays or modifications due to PABC (Additional file 1: Appendix 1). The form also asked “Did the patient stop breastfeeding while receiving breast cancer treatment? If yes, why?” Treatment and outcomes data were collected at the time of chart review - March 31, 2015. Outcomes were based on treatment notes documenting patients’ status as of this date and categorized as alive and in care, lost to follow-up and deceased. A patient was considered lost to follow-up if her last recorded clinic visit was six months or more prior to March 31, 2015 and there was no indication in her chart that she had finished treatment.

For detailed information on demographics, diagnostic delays and staging, we consulted a second database developed from surveys conducted as part of a separate study of diagnostic delays [21]. All women ages 21 or older with a breast complaint who were available at the time of survey administration were included in this study. This database was linked to the clinical database using unique patient identification numbers. For the current analysis, we used survey responses from women with pathologically confirmed cancer. Patient delay was calculated as the time between breast symptom onset and first presentation to a doctor or nurse and system delay was calculated as the time between the first visit to a doctor or nurse and the date of the first pathology report confirming breast cancer.

Analysis

We described demographic characteristics, diagnostic delays and stage at diagnosis for the women ages 21 and older contained in the secondary dataset. We used Wilcoxon rank sum and Fisher’s exact tests to compare characteristics of women with PABC to women with non-PABC at the alpha = 0.05 significance level. We described treatment and outcomes among women with PABC only, indicating any modifications made to treatment due to pregnancy or breastfeeding. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata v.13 (College Station, TX: Stata Corp LP).

Results

Characteristics of women with PABC

There were 252 women that presented to BCCOE with confirmed breast cancer within the study window, and 117 (46.4%) were between 18 and 50 years old (Fig. 1). Of these 117 patients, 12 (10.3%) met our criteria for having PABC. All 12 (100%) patients with PABC and 62 (59.0%) patients with non-PABC were contained in the secondary dataset (Table 1). The median age for women with PABC was 37 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 35, 38). Most women with PABC were married or in a relationship (n = 11, 91.7%) and had a primary school level of education or less (n = 6, 50.0%). Nine women (75.0%) had Mutuelle de Sante, the national health insurance, and 7 (58.3%) lived within one hour of the nearest health center. The only significant demographic differences between women with PABC and women with non-PABC were that women with PABC were significantly younger (p = 0.006) and more likely to be married (p = 0.035).

The median time from first onset of symptoms to first visit to a health facility (patient delay) was 109 days (IQR: 6.5, 325.5) for women with PABC and 139.5 days (IQR: 28, 402) for women with non-PABC (p = 0.367). The median time from first visit to a health facility and diagnosis (system delay) was 212 days (IQR: 58.5, 362) for women with PABC and 145 days (IQR: 59, 328) for women with non-PABC (p = 0.907). Three (25.0%) of the women with PABC had metastatic disease and 8 (66.7%) had tumors that were hormone receptor status positive. We did not identify any significant differences between women with PABC and women with non-PABC in terms of diagnostic delays or stage at presentation (Table 1).

PABC treatment and outcomes

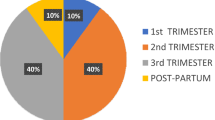

Among the 12 women identified as having PABC, 3 were pregnant at the time of diagnosis, and 9 were breastfeeding. Eleven patients (91.7%) underwent at least one treatment modality and one woman (who was pregnant at diagnosis) was lost to follow-up before starting treatment (Table 2). As first course of treatment, four (36.4%) women received endocrine therapy, five (45.5%) women received neoadjuvant IV chemotherapy, one (9.1%) woman received endocrine therapy and neoadjuvant IV chemotherapy and one (9.1%) woman underwent a mastectomy. Of the 11 patients who received any treatment, 3 women (27.2%) had indication of a delay or modification in treatment due to pregnancy or breastfeeding. Of these, two women delayed the start of treatment because of pregnancy and one woman delayed the start of treatment because she was breastfeeding. Four women (36.3%) were documented to have stopped breastfeeding in order to start treatment. One other woman stopped breastfeeding during her treatment, but the reasons were not specified. For the other 3 women who were breastfeeding at diagnosis and received treatment, cessation or continuation of breastfeeding was not documented in the record.

As of March 31, 2015, six (50.0%) of the women with PABC were alive, of which four (66.7%) were still receiving chemotherapy or endocrine therapy, one (16.7%) was on palliative care and one (16.7%) completed treatment. Three (25.0%) patients were deceased, all of which had metastatic disease at diagnosis and three (25.0%) patients were lost to follow-up.

Discussion

We identified 12 women with PABC who enrolled at BCCOE between July 1, 2012 and February 28, 2014, representing 10.3% of women ages 18–50 years diagnosed with breast cancer. The proportion of women with PABC is somewhat higher than rates documented in Europe (for example, 7.1% of women under 45 with breast cancer in Sweden [40]) but lower than rates documented in other sub-Saharan sites (for example, 21.2% of premenopausal women with breast cancer at a Nigerian hospital were diagnosed during or within two years after pregnancy [6]). However, we believe that our study underestimates the true rate of PABC prevalence at BCCOE since pregnancy and breastfeeding status in our cancer patients is not routinely documented. Women with PABC did experience considerable delays prior to diagnosis, with a median time of 109 days from symptom onset to first visit at a health facility, and 212 days from first visit to a health facility to initial diagnosis.

Based on our review of the literature, we hypothesized that women with PABC would experience longer diagnostic delays and as a result have more advanced disease at diagnosis [5, 25, 30, 41]. We did not find this in our population, which may be attributable to our small sample size which limited our power to detect differences between women with and without PABC. However, since long diagnostic delays have been observed in patients with PABC in other settings [3, 9, 27, 28, 42,43,44] and because most patients with breast cancer at BCCOE experience long diagnostic delays regardless of pregnancy and lactation status, [21] educational interventions for patients and providers in Rwanda are important for promoting earlier breast cancer detection, and should include the fact that breast cancer can occur during pregnancy and lactation. Leveraging existing health care interactions that occur for pregnant and breastfeeding women could make pregnancy an opportunity for early diagnosis instead of a risk factor for delay and late stage presentation [20, 21, 45, 46].

In our study, three women with PABC had documented modifications made to their treatment plan because of pregnancy or breastfeeding. Treatment considerations in PABC are complex and often require an individualized approach, though key principles (such as avoiding chemotherapy in the first trimester) should be disseminated in breast cancer treatment protocols [31]. Effective and safe treatment for patients with PABC also requires multidisciplinary collaboration [31]. At BCCOE, this often entailed email or phone consultations with surgical or medical oncologists and obstetricians based in Rwanda’s capital city or in the United States. Further investigations into how prognosis is associated with delayed or modified treatment because of pregnancy or breastfeeding in our setting are needed.

In addition to the psychosocial challenges faced by any young woman with a cancer diagnosis, patients in SSA and other low-income regions face particular challenges when diagnosed with PABC. Four patients stopped breastfeeding because of cancer treatment. While this can be important for the health of the baby, stopping breastfeeding is a particular challenge in Rwanda because of the expense of appropriate alternatives (e.g. infant formula) with resulting consequences for babies’ health. These challenges must be addressed by oncology programs in Rwanda and similar settings, through financial support for procurement of formula. Additionally, for women who are pregnant at diagnosis, therapeutic abortion may be the preferred choice, and in some settings therapeutic abortion may be legally, logistically, and culturally difficult to pursue. Research focused specifically on managing PABC in SSA and similar low-resource settings that have limited diagnostic and treatment capacity will be vital to understand the complex needs of these patients and address the increasing burden of the disease [40].

This study has several limitations. First, the small number of women with PABC limited our ability to detect differences in delays and stage at presentation. Second, PABC status is likely underreported because pregnancy or breastfeeding status is not systematically documented in our medical record system. Our findings underscore the importance of comprehensive and systematic data collection and management systems in LMICs in order to accurately assess patient diagnoses, treatment and outcomes. Third, due to a lack of sufficient follow-up time to have key outcomes data, we did not compare outcomes of patients with PABC patients to outcomes of patients with non-PABC. We plan to study this in the future, when we have more individuals and longer follow-up. Our findings are not necessarily generalizable to other settings in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly facilities that are not rural, or hospitals that are not cancer referral facilities. We suspect that in settings with more barriers to cancer care, the challenges facing women with PABC could be even more acute. Further research both in our settings and in others will help identify the range of issues that need to be addressed across the region.

Conclusion

This study highlights that PABC is an important clinical challenge among patients diagnosed with breast cancer in Rwanda. As the burden of breast cancer rises in LMICs, further research is needed to illuminate the scope of this issue, understand its medical, cultural and psychosocial implications for patients, and help develop context-specific management protocols in sub-Saharan Africa.

Abbreviations

- AJCC:

-

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- BCCOE:

-

Butaro Cancer Center of Excellence

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- LMICs:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- PABC:

-

Pregnancy-associated breast cancer

- RAMA:

-

Rwanda Assurance Maladie (Employed National Medical Insurance)

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- USA:

-

United States of America

References

American Cancer Society. Treating Breast Cancer During Pregnancy. Last revised 12/01/2014. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/breastcancer/moreinformation/pregnancy-and-breast-cancer. Accessed 20 July 2016.

Van Calsteren K, Heyns L, De Smet F, Van Eycken L, Gziri MM, Van Gemert W, et al. Cancer during pregnancy: An analysis of 215 patients emphasizing the obstetrical and the neonatal outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2009;28(4):683–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.23.2801.

Litton JK, Theriault RP, Gonzalez-Anjulo AM. Breast cancer diagnosis during pregnancy. Women’s Health (Lond Engl). 2009;5(3):243–9. https://doi.org/10.2217/whe.09.2.

Loibl S, von Minckwitz G, Gwyn K, Ellis P, Blohmer JU, Schlegelberger B, et al. Breast carcinoma during pregnancy: international recommendations from an expert meeting. Cancer. 2006;106(2):237–46.

Anderson JM. Mammary cancers and pregnancy. Br Med J. 1979;1(6171):1124–7.

Hou N, Ogundiran T, Ojengbede O, Morhason-Bello I, Zheng Y, Fackenthal J, et al. Risk factors for pregnancy-associated breast cancer: a report from the Nigerian breast Cancer study. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23(9):551–7.

Amant F, von Minckwitz G, Han SN, Bontenbal M, Ring AE, Giermek J, et al. Prognosis of women with primary breast cancer diagnosed during pregnancy: results from an international collaborative study. Journal Clin Oncol. 2013;31(20):2532–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.45.6335.

Theriault RL, Litton JK. Pregnancy during or after breast cancer diagnosis: what do we know and what do we need to know? J Clin Onc. 2013;31:2521–2. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.49.7347.

Woo JC, Yu T, Hurd TC. Breast cancer in pregnancy: a literature review. Arch Surg. 2003;138:91–8. discussion 99

Bonnier P, Romain S, Dilhuydy JM, Bonichon F, Julien JP, Charpin C, et al. Influence of pregnancy on the outcome of breast cancer: a case-control study. Int J Cancer. 1997;72:720–7.

Hassan I, Muhammed I, Attah MM, Maboqunje O. Breast cancer during pregnancy and lactation in Zaria, Nigeria. East Afr Med J. 1995;72(5):280–2.

Polivka J Jr, Altun I, Golubnitschaja O, et al. Pregnancy associated breast Cancer: the risky status quo and new concepts of predictive medicine. EPMA J. 2018;9(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13167-018-0129-7.

Amant F, Vandenbroucke T, Verheecke M, Fumagalli M, Halaska MJ, Boere I, et al. Pediatric outcome after maternal cancer diagnosed during pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1824–34. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1508913.

Meisel JL, Economy KE, Calvillo KZ, Schapira L, Tung NM, Gelber S, et al. Contemporary multidisciplinary treatment of pregnancy-associated breast cancer. Springerplus. 2013;2(1):297. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-2-297.

Assi HA, Khoury KE, Dbouk H, Khalil LE, Mouhieddine TH, Epidemiology ESNS. Prognosis of breast cancer in young women. J Thorac Dis. 2013;5(Suppl 1):S2–8. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.05.24.

Murphy CG, Mallam D, Stein S, Patil S, Howard J, Sklarin N, et al. Current or recent pregnancy is associated with adverse pathologic features but not impaired survival in early breast cancer. Cancer. 2012;118(13):3254–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26654.

DeSantis CE, Bray F, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Anderson BO, Jemal A. International variation in female breast cancer incidence and mortality rates. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2015;24(10):1495–506. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.

Kantelhardt EJ, Cubasch H, Hanson C. Taking on breast cancer in East Africa: global challenges in breast cancer. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;27(1):108–14. https://doi.org/10.1097/GCO.0000000000000139.

Brinton LA, Figueroa JD, Awuah B, Yarney J, Wiafe S, Woon SN, et al. Breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: opportunities for prevention. Breast Cancer Res and Treat. 2014;144(3):467–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-014-2868-z.

Anderson BO, Ilbawi AM, El Saghir NS. Breast cancer in low and middle income countries (LMICs): a shifting tide in global health. Breast J. 2015;21(1):111–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbj.12357.

Pace LE, Mpunga T, Hategekimana V, Dusengimana JM, Habineza H, Bigirimana JB, et al. Delays in breast cancer presentation and diagnosis at two rural cancer referral centers in Rwanda. Oncologist. 2015;207(7):780–8. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0493.

Donkor A, Lathlean J, Wiafe S, Vanderpuye V, Fenlon D, Yarney J, et al. Factors contributing to late presentation of breast cancer in Africa: a systematic literature review. Arch Med. 2015;8:2.

Gewefel H, Sarhia B. Breast cancer in adolescent and young adult women. Clinical Breast Cancer. 2014;14(6):390–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clbc.2014.06.002.

Mair LP. General characteristics of African family and marriage in African marriage and social change. New York: Routledge; 2013. p. 1–8.

Miranda JJ, Kinra S, Casas JP, Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. Non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: context, determinants and health policy. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13(10):1225–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.

Akarolo-Anthony SN, Ogundiran TO, Adebamowo CA. Emerging breast cancer epidemic: evidence from Africa. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12(Suppl 4):S8. https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr2737.

Chiedozi LC, Iweze FI, Aboh IF, Ajabor LN. Breast cancer in pregnancy and lactation. Trop Geogr Med. 1988;40(1):26–30.

Al-Amri AM. Clinical presentation and causes of the delayed diagnosis of breast cancer in patients with pregnancy associated breast cancer. J Family Community Med. 2015;22(2):96–100. https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8229.155383.

Sule EA, Ewemade F. Management of pregnancy associated breast cancer with chemotherapy in a developing country. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;17:117–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.10.008.

Ibrahim NA, Oludara MA. Socio-demographic factors and reasons associated with delay in breast cancer presentation: a study in Nigerian women. Breast. 2012;21(3):416–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2012.02.006.

Shachar SS, Gallagher K, McGuire K, Zagar TM, Faso A, Muss HB, et al. Multidisciplinary Management of Breast Cancer during Pregnancy. Oncologist. 2017;22:324–34.

Murthy SS, Tapela N, Muhimpundu MA, Balinda JP, Musabyemariya F, Kirby K. A national framework for breast cancer control: a report on Rwanda’s inaugural symposium on the management of breast cancer. J Cancer Policy. 2015;6:3–7.

Tapela NM, Mpunga T, Hedt-Gauthier B, Moore M, Mpanumusingo E, Xu MJ, et al. Pursuing equity in cancer care: implementation, challenges and preliminary findings of a public cancer referral center in rural Rwanda. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:237. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2256-77.

Shulman LN, Mpunga T, Tapela N, Wagner CM, Fadelu T, Binagwago A. Bringing cancer care to the poor: experiences from Rwanda. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(12):815–21. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3848.

Mubiligi JM, Hedt-Gauthier B, Mpunga T, Tapela N, Okao P, Harries AD, et al. Caring for patients with surgically resectable cancers: experience from a specialized center in rural Rwanda. Public Health Action. 2014;4(2):128–32. https://doi.org/10.5588/pha.14.0002.

O’Neil DS, Keating NL, Dusengimana JMV, Hategekimana V, Umwizera A, Mpunga T, et al. Quality of breast cancer treatment at a rural cancer center in Rwanda. J Global Onc Published online before print May 12, 2017. doi:https://doi.org/10.1200/JGO.2016.008672.

Rubagumya F, Greenbergy L, Manirakiza A, DeBoer R, Park PH, Mpunga T, Shulman LN. Increasing global access to cancer care: models of care with non-oncologists as primary providers. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1000–2.

Edge SB, Compton CC. The American joint committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC Cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(6):1471–4.

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda, Ministry of Health Rwanda, and ICF International. Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey 2010. Calverton: National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda, Ministry of Health Rwanda, and ICF International; 2012.

Andersson TM, Johansson AL, Hsieh CC, Cnattingius S, Lambe M. Increasing incidence of pregnancy-associated breast cancer in Sweden. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(3):568–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b19154.

Yang YL, Chan KA, Hsieh FJ, Chang LY, Wang MY. Pregnancy-associated breast cancer in Taiwanese women: potential treatment delay and impact on survival. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e111934. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0111934.

Anderson BO, Petrek JA, Byrd DR, Senie RT, Borgen PI. Pregnancy influences breast cancer stage at diagnosis in women 30 years of age and younger. Ann Surg Oncol. 1996;3:204–11.

Ishida T, Yokoe T, Kasumi F, Sakamoto G, Makita M, Tominaga T, Simozuma K, Enomoto K, Fujiwara K, Nanasawa T, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics and prognosis of breast cancer patients associated with pregnancy and lactation: analysis of case–control study in Japan. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1992;83:1143–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1349-7006.1992.tb02737.x.

Basaran D, Turgal M, Beksac K, Ozyuncu O, Aran O, Beksac MS. Pregnancy-associated breast cancer: Clinicopathological characteristics of 20 cases with focus on identifiable causes of diagnostic delay. Breast Care. 2014;9:355–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000366436.

Galukande M, Kiguli-Malwadde E. Rethinking breast cancer screening strategies in resource-limited settings. Afr Health Sci. 2010;10(1):89–92.

Adebamowo CA, Akarolo-Anthony S. Cancer in Africa: opportunities for collaborative research and training. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2009;38(Suppl 2):5–13.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Partners In Health/Inshuti Mu Buzima Intermediate Operational Research Training Program under which this study was developed and funded.. We acknowledge the leadership and clinicians for facilitating data collection. We also acknowledge Michel Abewe, who reviewed the patient charts for PABC indications.

Funding

The Intermediate Operational Research Training Program, including some of the data collection costs, was supported by Partners In Health/Inshuti Mu Buzima-Rwanda and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, grant BCRF-17-147. The sub-cohort data collection, analysis and manuscript writing for the delays study was funded by Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the Global Women’s Health Fellowship at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Availability of data and materials

The data that supports the findings of this study is available from the Rwanda Ministry of Health and Partners In Health/Inshuti Mu Buzima, but restrictions apply to the availability of the data, which was used with permission for the current study and therefore not publicly available. Data is however available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with permission of Partners In Health/Inshuti Mu Buzima and the Ministry of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception/Design: LP, VH, JMVD, TM, LS and ST; Data collection: VH, JMVD, TM, IN, TF, and LP; Data analysis: VH, JMVD, LP, RB and BHG; Results interpretation: All co-authors Manuscript writing: JMVD, VH, LP, RB, BHG and NG; Final approval of manuscript: All co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

There were two data sources included in this study; both received ethics approval from the Rwanda National Ethics Committee (Rwanda) and Partners Institutional Review Board (Boston, USA). The first data source was a chart extraction of routinely collected clinical data. Because there was no direct contact with patients and minimal risks, both ethics committees waived the need for consent for that aspect of the project. The second data source was collected as part of an ongoing study [21]; women were consented prior to data collection as part of the study. The consent obtained was written.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional files 1:

Appendix 1, Portion of data collection form designed by researchers to record delays, deviations and modifications in treatment for PABC cohort. This form was used during the medical record abstraction process to identify treatment delays and modifications due to pregnancy or breastfeeding for patients with PABC. (DOCX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Dusengimana, J.M.V., Hategekimana, V., Borg, R. et al. Pregnancy-associated breast cancer in rural Rwanda: the experience of the Butaro Cancer Center of Excellence. BMC Cancer 18, 634 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4535-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4535-y