Abstract

Background

Herein, we collected currently published data to comprehensively evaluate the impact of the FCGR2A (Fc fragment of IgG receptor IIa) rs1801274 and MUC5B (mucin 5B, oligomeric mucus/gel-forming) rs35705950 variations on susceptibility to pneumonia diseases.

Methods

We retrieved case-control studies from three online databases and applied the statistical approach of meta-analysis for a series of pooling analyses.

Results

A total of fourteen case-control studies were included for FCGR2A rs1801274; while thirty-one case-control studies were included for MUC5B rs35705950. No significant difference between pneumonia cases and controls for FCGR2A rs1801274 was found. However, MUC5B rs35705950 was significantly associated with pneumonia susceptibility in the whole population under the genetic models of allelic T vs. G [OR (odds ratio) =3.78], carrier T vs. G (OR = 3.31), TT vs. GG (OR = 13.66), GT vs. GG (OR = 4.78), GT + TT vs. GG (OR = 5.05), and TT vs. GG + GT (OR = 6.47) (all P < 0.001, Bonferroni-adjusted P < 0.006; false discovery rate-adjusted P < 0.0010). Furthermore, we observed a similar positive result for subgroup analyses of “Caucasian”, “Asian”, “population-based control”, and “idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis”.

Conclusions

MUC5B rs35705950, but not FCGR2A rs1801274, increases susceptibility to clinical pneumonia, especially to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, in both the Caucasian and Asian populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pneumonia is a group of viral or bacterial infection-induced lung disorders that can cause the symptoms of fever, cough, shortness of breath and fatigue [1,2,3]. There are various types of pneumonia, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP) [4,5,6]. Although the pathogenesis of pneumonia remains elusive, environmental exposure factors (e.g., tobacco smoking, virus or bacterial infection) and genetic variants may contribute to the susceptibility to pneumonia [2, 7, 8]. Here, we investigated pneumonia-associated gene variations. After database retrieval and publication selection, we excluded reports of potential pneumonia-associated gene variation without enough or updated data, and finally focused on two variants, namely, FCGR2A rs1801274 and MUC5B rs35705950.

The human FCGR2A gene in the 1q23 chromosome region encodes a member of the heterogeneous Fc fragment of the IgG receptor family of immune receptors and contains a functional rs1801274 variation in exon 4, which leads to the amino acid alteration from histidine (H) to arginine (R) at position 131 of the FCGR2A protein [9, 10]. No prior meta-analysis regarding the genetic role of FCGR2A rs1801274 in pneumonia susceptibility has been reported, and studies have reported different findings [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Therefore, this is the first pooling analysis that has been conducted to assess the potential association between FCGR2A rs1801274 and overall pneumonia risk and was carried out according to PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) guidelines.

Human MUC5B, a gel-forming mucin gene in the 11p15.5 chromosome region [21], can be expressed by certain bronchial epithelial cells and contains several variations (such as rs35705950) in a three kilobase region upstream of the MUC5B transcription start site [22, 23]. We found one meta-analysis published in 2013 [24] and two meta-analyses published in 2015 [25, 26] regarding the association between MUC5B rs35705950 and the risk of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. However, only ten studies were included, and the genetic association between MUC5B rs35705950 and the susceptibility to other pneumonia types has not yet been investigated. Therefore, we performed an updated meta-analysis to comprehensively assess the effect of MUC5B rs35705950 on the risk of overall pneumonia disease based on available case-control studies as of February 2020.

Methods

Database search and study identification

Referring to similar investigations [27, 28], we collected potentially relevant studies from three databases, including PubMed, EMBASE (Excerpta Medica Database), and WOS (Web of Science), on 25 February 2020. To prevent the filtering of the possible eligible studies, in the retrieval strategy, we utilized a combination of subject words [“MeSH (medical subject headings)” for PubMed and “Emtree” for EMBASE] and free words (“Entry Terms” for PubMed, “synonyms” for EMBASE) in the retrieval strategy. No restriction on publication language or region was applied. The detailed search terms can be found in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Based on our exclusion/inclusion criteria, we then performed the study identification and eligibility assessment. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) meta-analysis, comment or review; (ii) mice or cell data; (iii) conference abstract or case reports; (iv) other gene or disease; (v) lack of normal controls or specific data; and (vi) not in line with HWE (Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium) principle. Only those studies with allelic or genotypic frequency data from both the pneumonia cases and negative controls were enrolled.

Evidence collection and quality appraisal

After full-text verification of each case-control study, we extracted and sorted the basic information (e.g., the first name of the author, publication date, race, variation, frequency) in Excel files. We also contacted corresponding authors by email in an attempt to retrieve any missing data of allelic or genotypic frequency. We also applied the NOS (Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale) system to evaluate the study quality.

Statistical approaches

To assess the statistical heterogeneity between studies, we performed I2/Q statistical tests by means of the STATA software (version 12.0 Stata Corporation, USA). The DerSimonian-Laird random effects model was used for high heterogeneity [I2 > 50% or Pheterogeneity (P value in the heterogeneity test) < 0.05]; while the Mantel-Haenszel method for fixed-effect models was used for low or no heterogeneity (I2 < 50% and Pheterogeneity > 0.05). We also utilized the STATA software to conduct association tests and obtained the OR, 95% confidence interval (CI) and Passociation (P value in the association test) under a total of six models to assess the association strength.

Referencing the relevant literature [29, 30], we also adjusted the P value in the association tests using the p.adjust function of the R software, version 3.6.1. P values adjusted for the Bonferroni and false discovery rate (FDR) were also obtained. Furthermore, we performed a false-positive report probability (FPRP) analysis to assess the probability of a true genetic relationship using the genetic analysis “gap” R package [31, 32] [FPRP cutoff value = 0.2, power OR = 1.5, and prior probability levels = (0.25, 0.1, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001, 0.00001)].

Trial sequential analysis

Referencing the previous studies [33, 34], we carried out the trial sequential analysis (TSA) test for the assessment of conclusion robustness using the TSA viewer software (http://www.ctu.dk/tsa/) (type I error probability = 5%, statistical test power = 80%, and relative risk reduction =20%).

Publication bias and sensitivity analyses

Additionally, we conducted a group of subgroup analyses by the factors of race, control source, and pneumonia type. We also carried out the Begg and Egger tests for analyzing the presence of publication bias, and the sensitivity analysis was conducted using one-by-one removal of each study to evaluate data stability.

Results

Eligible case-control study characteristics

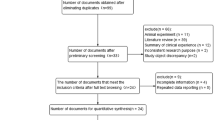

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of selecting eligible case-control studies. Utilizing the computerized database search process, we collected a total of 234 records (PubMed 87 records, EMBASE 18 records, and WOS 158 records). We then removed 32 duplicate records, as well as 164 records due to the following exclusion criteria: meta, comment or review (n = 101), mice or cell (n = 17), conference abstract or case report (n = 9), other gene or disease (n = 37). Another 16 records were excluded due to “lack of normal control or specific data” or “not in line with HWE”. Finally, a total of twenty-two articles [8, 11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20, 23, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] were included in the quantitative synthesis. Fourteen case-control studies from ten articles [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] were included in the meta-analysis of FCGR2A rs1801274; while thirty-one case-control studies from twelve articles [8, 23, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] were included for MUC5B rs35705950. Table 1 presents a summary of the basic information, while Additional file 1: Table S2 presents the detailed allelic and genotypic frequency data of the enrolled case-control studies. All studies were of high quality (all NOS score > =5), as shown in Additional file 1: Table S3.

FCGR2A rs1801274

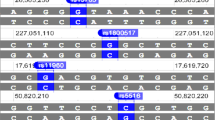

As presented in Table 2, the lack of high inter-study heterogeneity (I2 = 26.0%, Pheterogeneity = 0.182) resulted in using a fixed-effect model for the carrier G vs. A model, whereas a random-effect model was applied for the others. Upon the pooling analysis of thirteen studies (1332 cases /5428 controls) of the overall population, we failed to observe a significant difference between pneumonia cases and negative controls under the allelic G vs. A, carrier G vs. A, GG vs. AA, AG vs. AA, AG + GG vs. AA, or GG vs. AA+AG models (Table 3, all Passociation > 0.05; Bonferroni-Passociation > 0.05; FDR-Passociation > 0.05). Next, we conducted a series of subgroup analyses by race or control source under the six genetic models. As shown in Table 3, we observed similar negative results in all subgroups (all Passociation > 0.05, Bonferroni-Passociation > 0.05; FDR-Passociation > 0.05), except in the subgroup analysis of “HB” under the AG vs. AA model (Passociation = 0.023, Bonferroni-Passociation = 0.138; FDR-Passociation = 0.1380). Fig. 2 shows the forest plot data under the allelic model (as an example). These findings showed that FCGR2A rs1801274 may not be strongly associated with overall pneumonia susceptibility.

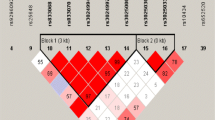

MUC5B rs35705950

For the pooling analysis of MUC5B rs35705950, we included a total of thirty-one studies with 5644 cases and 14,624 controls (Table 4) in the overall population. The lack of high inter-study heterogeneity led to using a fixed-effect model for the carrier G vs. A model (Table 2, I2 = 0.7%, Pheterogeneity = 0.449), TT vs. GG (I2 = 0.0%, Pheterogeneity = 0.870), and TT vs. GG + GT (I2 = 0.0%, Pheterogeneity = 0.959), but a random-effect model was used for the others. The pooling results in Table 4 show a significant association between MUC5B rs35705950 and high susceptibility to pneumonia in the overall population under the genetic models of allelic T vs. G (OR = 3.78), carrier T vs. G (OR = 3.31), TT vs. GG (OR = 13.66), GT vs. GG (OR = 4.78), GT + TT vs. GG (OR = 5.05), and TT vs. GG + GT (OR = 6.47) (all Passociation < 0.001, Bonferroni-Passociation < 0.006; FDR-Passociation < 0.0010). Subsequently, we observed similar positive correlations in the followed subgroup analyses of “Caucasian”, “PB”, and “IPF” under all genetic models (Table 4, OR > 3, Passociation < 0.01, Bonferroni-Passociation < 0.006; FDR-Passociation < 0.0010). In the “NSIP” subgroup, we detected positive results under the allelic (Table 4, OR = 3.01), carrier (OR = 2.66), and GT + TT vs. GG (OR = 3.19) (Passociation < 0.001, Bonferroni-Passociation < 0.006; FDR-Passociation < 0.0015). In the “Asian” subgroup, we also observed a positive association between MUC5B rs35705950 and the high risk of pneumonia under the genetic models of allelic T vs. G (OR = 2.76), carrier T vs. G (OR = 2.47), GT vs. GG (OR = 2.78), and GT + TT vs. GG (OR = 2.78) (all Passociation < 0.001, Bonferroni-Passociation < 0.006; FDR-Passociation < 0.0010). Furthermore, based on the applicable conditions of FPRP [31, 32], we applied FPRP analysis for the data of the “Asian” subgroup. As shown in Additional file 1: Table S4, the observed FPRP values under the prior probability level of 0.1 were all less than 0.20, confirming notable associations. Forest plots of the subgroup analyses are presented in Figs. 3 and 4 and Additional file 2: Figures S1-S6. The above evidence demonstrated that MUC5B rs35705950 is closely linked to a high susceptibility to pneumonia diseases, especially to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, in the Asian and Caucasian populations.

Publication bias

As shown in Table 2, we did not observe a large publication bias among the comparisons, as evidenced by PBegg > 0.05 and PEgger > 0.05 for all models except the Egger test under GT vs. GG (PEgger = 0.002) and GT + TT vs. GG (PEgger = 0.002) for MUC5B rs35705950. Fig. 5a and Additional file 2: Figure S7a display the Begg test plot under the allelic model (as an example).

Sensitivity and TSA data

We observed relatively stable pooling data in the sensitivity analyses of FCGR2A rs1801274 (e.g., Additional file 2: Figure S7b for the allelic model). However, our TSA test data (Figure S8) showed that the cumulative Z-curve did not totally reach the conventional boundary and required information size, suggesting the requirement for a larger sample size to confirm the negative association between FCGR2A rs1801274 and pneumonia risk.

With regards to MUC5B rs35705950, we found that the cumulative Z-curve of GT + TT vs. GG model can cross the TSA monitoring boundary despite not reaching the required information size in the overall population (Additional file 2: Figure S9), Caucasian population (Additional file 2: Figure S10), and Asian population (Additional file 2: Figure S11), indicating the robustness of the conclusions. Furthermore, we also observed the relatively stable or credible outcomes for the MUC5B rs35705950 through the sensitivity analyses (e.g., Fig. 5b for the allelic model).

Discussion

The inconclusive result of the genetic influence of FCGR2A rs1801274 on the susceptibility to clinical pneumonia has been observed in previous studies. For example, a negative effect of FCGR2A rs1801274 was detected for the development of pneumonia in systemic lupus erythematosus patients [15]; additionally, FCGR2A rs1801274 was not found to increase the risk of invasive pneumococcal disease in Belgium [16]. Although FCGR2A rs1801274 was not identified in any genome-wide association study (GWAS) of pneumonia [8, 22], we observed a positive association between FCGR2A rs1801274 and the risk of pneumonia. FCGR2A rs1801274 was reported to be significantly associated with the risk of severe pneumonia in A/H1N1 influenza infection [20], bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia infection [18], and the severity of community-acquired pneumonia [12]. Here, for the first time, we carried out a meta-analysis and TSA test to comprehensively evaluate the genetic influence of FCGR2A rs1801274 in the susceptibility to clinical pneumonia. Upon pooling a total of 1332 cases and 5428 controls from thirteen studies, no strong evidence was found to support a significant association between FCGR2A rs1801274 and overall pneumonia risk.

In 2013, Borie, R. et al. included four case-control studies from three articles [23, 24, 44] to perform a meta-analysis of the association between MUC5B rs35705950 and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis risk [24]. A total of nine case-control studies from seven articles [8, 23, 24, 36, 40, 42, 45] were included in another meta-analysis by Zhu, Q. Q. in 2015 [26]; while twelve case-control studies from eight articles [8, 23, 24, 36, 40, 42, 43, 46] were included in an updated meta-analysis by Lee, M. G. et al., 2015 [25]. Given the differences in study selection, basic information extraction, pooling strategies and data description, we carried out a quantitative synthesis to assess the effect of MUC5B rs35705950 on the risk of pneumonia diseases, including idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia.

In the present study, we performed the extensive retrieval of three databases (as of 25 February 2020) to capture potential publications for inclusion in a series of pooling analyses. Based on our strict screening strategy, we included a total of 5644 cases and 14,624 controls across thirty-one studies in the overall meta-analysis, followed by subgroup analyses according to the factors of race, control source and pneumonia type. A total of six genetic models, namely, allelic, carrier, homozygotic, heterozygotic, dominant and recessive, were applied. We excluded the studies based on the strict requirements of the HWE principle. Our pooling data suggest that MUC5B rs35705950 is closely associated with an increased risk of pneumonia diseases, especially idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, in both Asians and Caucasians. The positive genetic relationship between MUC5B rs35705950 and high susceptibility to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is consistent with the results of previous meta-analyses [24,25,26] and GWAS evidence [8, 22]. When comparing the OR value under different genetic models, the TT genotype carriers were found to be more susceptible to pneumonia disease than the GT genotype carriers. It is possible that the “T” allele of MUC5B rs35705950 confers an enhanced susceptibility to pneumonia patients in a dose-dependent manner.

Our study has several advantages over other studies. First, none of the included case-control studies were of low quality based on the assessment analysis of the NOS system. Second, we excluded case-control studies in which the genotypic distribution in the control group did not conform to the HWE principle. Third, we found no obvious evidence of a large publication bias, according to the Begg and Egger analyses. Fourth, we observed the stability of the pooling data when applying our leave-one-out sensitivity analysis, along with the FPRP and TSA analyses. Our study enables readers to understand the current research status of pneumonia-related MUC5B rs35705950 in different populations, as well as the pooling evidence based on the currently available data.

However, some disadvantages of our study may affect our statistical power. There was high inter-study heterogeneity in some comparisons. Despite thirteen case-control studies being included in the overall pooling analysis for FCGR2A rs1801274, certain subgroups contained small sample sizes. For example, very limited case-control studies in the subgroup analysis of “specific pneumonia type” deterred us from performing the relative analysis. No cases in the homogenous Asian population were enrolled for pooling analysis. Although we observed a negative result in the pooling analysis based on the presently available data, our new TSA test for FCGR2A rs1801274 indicated the necessity for a larger sample size to confirm the negative association between FCGR2A rs1801274 and pneumonia risk both the Caucasian and Asian populations.

We observed a positive association between MUC5B rs35705950 and the overall risk of pneumonia in the Asian population. We also performed FPRP and TSA tests to confirm this relationship. However, there were only five case-control studies, and we could not perform further pooling analysis based on the different phenotypes due to the limited available data. Likewise, only four case-control studies were included in the subgroup analysis of “NSIP”. We failed to detect a genetic influence of MCU5B rs35705950 on the risk of other pneumonia types, such as idiopathic interstitial pneumonia, chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and familial interstitial pneumonia.

When more case-control studies become available, it would be meaningful to take additional factors into consideration, such as gender, age, exposure, and drinking/smoking status. As mentioned above, FCGR2A rs1801274 and MUC5B rs35705950 were selected due to the research status of pneumonia-related variations and the novelty of the data analysis. Thus, there is no obvious correlation between the two. Nevertheless, it is still meaningful to analyze the combined impact of different variants of other genes [e.g., rs2736100 in TERT (telomerase reverse transcriptase)] on the susceptibility to the different types of pneumonia in different populations when the data become available.

Conclusion

Our findings revealed that MUC5B rs35705950 is strongly linked to an increased risk of pneumonia diseases in the Asian and Caucasian populations. Owing to data limitations, more available evidence is required to further clarify the genetic relationship between FCGR2A rs1801274 and pneumonia susceptibility.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- FCGR2A:

-

Fc fragment of IgG receptor IIa

- MUC5B:

-

Mucin 5B, oligomeric mucus/gel-forming

- AIDS:

-

Immune deficiency syndrome

- IPF:

-

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- NSIP:

-

Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia

- IIP:

-

Idiopathic interstitial pneumonia

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- EMBASE:

-

Excerpta Medica Database

- WOS:

-

Web of Science

- MeSH:

-

Medical subject headings

- HWE:

-

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

- NOS:

-

Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- FDR:

-

False discovery rate

- FPRP:

-

False-positive report probability

- TSA:

-

Trial sequential analysis

- GWAS:

-

Genome-wide association study

- TERT:

-

Telomerase reverse transcriptase

References

Lanks CW, Musani AI, Hsia DW. Community-acquired pneumonia and hospital-acquired pneumonia. Med Clin North Am. 2019;103(3):487–501.

Galvan JM, Rajas O, Aspa J. Review of non-bacterial infections in respiratory medicine: viral pneumonia. Arch Bronconeumol. 2015;51(11):590–7.

Lutfiyya MN, Henley E, Chang LF, Reyburn SW. Diagnosis and treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. Am Fam Physician. 2006;73(3):442–50.

Taniguchi H, Kondoh Y. Acute and subacute idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Respirology. 2016;21(5):810–20.

Sgalla G, Iovene B, Calvello M, Ori M, Varone F, Richeldi L. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: pathogenesis and management. Respir Res. 2018;19(1):32.

Wells AU, Cottin V. Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia: time to be more specific? Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2016;22(5):450–5.

Mizgerd JP. Pathogenesis of severe pneumonia: advances and knowledge gaps. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2017;23(3):193–7.

Noth I, Zhang Y, Ma SF, Flores C, Barber M, Huang Y, Broderick SM, Wade MS, Hysi P, Scuirba J, et al. Genetic variants associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis susceptibility and mortality: a genome-wide association study. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1(4):309–17.

Khor CC, Davila S, Breunis WB, Lee YC, Shimizu C, Wright VJ, Yeung RS, Tan DE, Sim KS, Wang JJ, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies FCGR2A as a susceptibility locus for Kawasaki disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43(12):1241–6.

Wu J, Lin R, Huang J, Guan W, Oetting WS, Sriramarao P, Blumenthal MN. Functional Fcgamma receptor polymorphisms are associated with human allergy. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89196.

Bougle A, Max A, Mongardon N, Grimaldi D, Pene F, Rousseau C, Chiche JD, Bedos JP, Vicaut E, Mira JP. Protective effects of FCGR2A polymorphism in invasive pneumococcal diseases. Chest. 2012;142(6):1474–81.

Endeman H, Cornips MC, Grutters JC, van den Bosch JM, Ruven HJ, van Velzen-Blad H, Rijkers GT, Biesma DH. The Fcgamma receptor IIA-R/R131 genotype is associated with severe sepsis in community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16(7):1087–90.

Forthal DN, Landucci G, Bream J, Jacobson LP, Phan TB, Montoya B. FcgammaRIIa genotype predicts progression of HIV infection. J Immunol. 2007;179(11):7916–23.

Jonsson G, Oxelius VA, Truedsson L, Braconier JH, Sturfelt G, Sjoholm AG. Homozygosity for the IgG2 subclass allotype G2M(n) protects against severe infection in hereditary C2 deficiency. J Immunol. 2006;177(1):722–8.

Kinder BW, Freemer MM, King TE Jr, Lum RF, Nititham J, Taylor K, Edberg JC, Bridges SL Jr, Criswell LA. Clinical and genetic risk factors for pneumonia in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(8):2679–86.

Moens L, Van Hoeyveld E, Verhaegen J, De Boeck K, Peetermans WE, Bossuyt X. Fcgamma-receptor IIA genotype and invasive pneumococcal infection. Clin Immunol. 2006;118(1):20–3.

Sole-Violan J, Garcia-Laorden MI, Marcos-Ramos JA, de Castro FR, Rajas O, Borderias L, Briones ML, Herrera-Ramos E, Blanquer J, Aspa J, et al. The Fcgamma receptor IIA-H/H131 genotype is associated with bacteremia in pneumococcal community-acquired pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(6):1388–93.

Yee AM, Phan HM, Zuniga R, Salmon JE, Musher DM. Association between FcgammaRIIa-R131 allotype and bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(1):25–8.

Yuan FF, Wong M, Pererva N, Keating J, Davis AR, Bryant JA, Sullivan JS. FcgammaRIIA polymorphisms in Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. Immunol Cell Biol. 2003;81(3):192–5.

Zuniga J, Buendia-Roldan I, Zhao Y, Jimenez L, Torres D, Romo J, Ramirez G, Cruz A, Vargas-Alarcon G, Sheu CC, et al. Genetic variants associated with severe pneumonia in a/H1N1 influenza infection. Eur Respir J. 2012;39(3):604–10.

Adegunsoye A, Vij R, Noth I. Integrating genomics into Management of Fibrotic Interstitial Lung Disease. Chest. 2019;155(5):1026–40.

Fingerlin TE, Murphy E, Zhang W, Peljto AL, Brown KK, Steele MP, Loyd JE, Cosgrove GP, Lynch D, Groshong S, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies multiple susceptibility loci for pulmonary fibrosis. Nat Genet. 2013;45(6):613–20.

Seibold MA, Wise AL, Speer MC, Steele MP, Brown KK, Loyd JE, Fingerlin TE, Zhang W, Gudmundsson G, Groshong SD, et al. A common MUC5B promoter polymorphism and pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(16):1503–12.

Borie R, Crestani B, Dieude P, Nunes H, Allanore Y, Kannengiesser C, Airo P, Matucci-Cerinic M, Wallaert B, Israel-Biet D, et al. The MUC5B variant is associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis but not with systemic sclerosis interstitial lung disease in the European Caucasian population. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70621.

Lee MG, Lee YH. A meta-analysis examining the association between the MUC5B rs35705950 T/G polymorphism and susceptibility to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Inflamm Res. 2015;64(6):463–70.

Zhu QQ, Zhang XL, Zhang SM, Tang SW, Min HY, Yi L, Xu B, Song Y. Association between the MUC5B promoter polymorphism rs35705950 and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a Meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis in Caucasian and Asian populations. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(43):e1901.

Sun M, Zhong J, Zhang L, Shi S. Genetic impact of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) polymorphism on the susceptibility to colorectal polyps: a meta-analysis. BMC Med Genet. 2019;20(1):94.

Qi Y, Kong J, He J. Genetic relationship between IL-10 gene polymorphisms and the risk of clinical atopic dermatitis. BMC Med Genet. 2019;20(1):83.

Su H, Rei N, Zhang L, Cheng J. Meta-analyses of IL1A polymorphisms and the risk of several autoimmune diseases published in databases. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0198693.

Zhang J, Wu J, Peng X, Song J, Wang J, Dong W. Associations between STAT3 rs744166 polymorphisms and susceptibility to ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109625.

Wacholder S, Chanock S, Garcia-Closas M, El Ghormli L, Rothman N. Assessing the probability that a positive report is false: an approach for molecular epidemiology studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(6):434–42.

Zhao JH. gap: genetic analysis package. J Stat Softw. 2007;23(8).

Dai Y, Song Z, Zhang J, Gao W. Comprehensive assessment of the association between XPC rs2228000 and cancer susceptibility based on 26835 cancer cases and 37069 controls. Biosci Rep. 2019;39(12). https://doi.org/10.1042/BSR20192452.

Fu W, Zhuo ZJ, Chen YC, Zhu J, Zhao Z, Jia W, Hu JH, Fu K, Zhu SB, He J, et al. NFKB1 -94insertion/deletion ATTG polymorphism and cancer risk: evidence from 50 case-control studies. Oncotarget. 2017;8(6):9806–22.

Dressen A, Abbas AR, Cabanski C, Reeder J, Ramalingam TR, Neighbors M, Bhangale TR, Brauer MJ, Hunkapiller J, Reeder J, et al. Analysis of protein-altering variants in telomerase genes and their association with MUC5B common variant status in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a candidate gene sequencing study. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(8):603–14.

Horimasu Y, Ohshimo S, Bonella F, Tanaka S, Ishikawa N, Hattori N, Kohno N, Guzman J, Costabel U. MUC5B promoter polymorphism in Japanese patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology. 2015;20(3):439–44.

Johnson C, Rosen P, Lloyd T, Horton M, Christopher-Stine L, Oddis CV, Mammen AL, Danoff SK. Exploration of the MUC5B promoter variant and ILD risk in patients with autoimmune myositis. Respir Med. 2017;130:52–4.

Kishore A, Zizkova V, Kocourkova L, Petrkova J, Bouros E, Nunes H, Lostakova V, Muller-Quernheim J, Zissel G, Kolek V, et al. Association study for 26 candidate loci in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients from four European populations. Front Immunol. 2016;7:274.

Ley B, Newton CA, Arnould I, Elicker BM, Henry TS, Vittinghoff E, Golden JA, Jones KD, Batra K, Torrealba J, et al. The MUC5B promoter polymorphism and telomere length in patients with chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: an observational cohort-control study. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(8):639–47.

Stock CJ, Sato H, Fonseca C, Banya WA, Molyneaux PL, Adamali H, Russell AM, Denton CP, Abraham DJ, Hansell DM, et al. Mucin 5B promoter polymorphism is associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis but not with development of lung fibrosis in systemic sclerosis or sarcoidosis. Thorax. 2013;68(5):436–41.

van der Vis JJ, Snetselaar R, Kazemier KM, ten Klooster L, Grutters JC, van Moorsel CH. Effect of Muc5b promoter polymorphism on disease predisposition and survival in idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Respirology. 2016;21(4):712–7.

Wang C, Zhuang Y, Guo W, Cao L, Zhang H, Xu L, Fan Y, Zhang D, Wang Y. Mucin 5B promoter polymorphism is associated with susceptibility to interstitial lung diseases in Chinese males. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e104919.

Wei R, Li C, Zhang M, Jones-Hall YL, Myers JL, Noth I, Liu W. Association between MUC5B and TERT polymorphisms and different interstitial lung disease phenotypes. Transl Res. 2014;163(5):494–502.

Zhang Y, Noth I, Garcia JG, Kaminski N. A variant in the promoter of MUC5B and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(16):1576–7.

Peljto AL, Selman M, Kim DS, Murphy E, Tucker L, Pardo A, Lee JS, Ji W, Schwarz MI, Yang IV, et al. The MUC5B promoter polymorphism is associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in a Mexican cohort but is rare among Asian ancestries. Chest. 2015;147(2):460–4.

Zhang GY, Liao T, Gao WY. MUC5B promoter polymorphism and pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(2):178 author reply −9.

Acknowledgments

We appreciated the help of Yue Cui (Tianjin Huanhu Hospital) during pooling analysis. We are also grateful to American Journal Experts for help with English language editing.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XS and YM performed the database search and study identification. XS, YM and HL performed the pooling analysis, FPRP and TSA test. XS, YM and HY wrote the manuscript. HY was responsible for reviewing the data. All the authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1 Table S1

. Detailed terms of database search (as of 25 February 2020). Table S2. Allelic and genotypic frequency data of the included case-control studies. Table S3. Quality assessment of included case-control studies. Table S4. FPRP values for the association between MUC5B rs35705950 and pneumonia risk in the Asian population. (DOCX 52.4 KB)

Additional file 2 Figure S1.

Subgroup analysis data of “control source” for MUC5B rs35705950 under the allelic model. Figure S2. Subgroup analysis data of “pneumonia type” for MUC5B rs35705950 under the carrier model. Figure S3. Subgroup analysis data of “pneumonia type” for MUC5B rs35705950 under the TT vs. GG model. Figure S4. Subgroup analysis data of “pneumonia type” for MUC5B rs35705950 under the GT vs. GG model. Figure S5. Subgroup analysis data of “pneumonia type” for MUC5B rs35705950 under the GT + TT vs. GG model. Figure S6. Subgroup analysis data of “pneumonia type” for MUC5B rs35705950 under the TT vs. GG + GT model. Figure S7. Sensitivity analysis (a) and Begg test data (b) for FCGR2A rs1801274 under the allelic T vs. G model. Figure S8. TSA data for FCGR2A rs1801274 under the AG + GG vs. AA model. Figure S9. TSA data for MUC5B rs35705950 under the GT + TT vs. GG model in the overall populations; Figure S10. TSA data for MUC5B rs35705950 under the GT + TT vs. GG model in the Caucasian population; Figure S11. TSA data for MUC5B rs35705950 under the GT + TT vs. GG model in the Asian population. (PDF 1.9 MB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, X., Ma, Y., Li, H. et al. Association between FCGR2A rs1801274 and MUC5B rs35705950 variations and pneumonia susceptibility. BMC Med Genet 21, 71 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-020-01005-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-020-01005-1