Abstract

Background

It is important to understand clinical features of bacteremic urinary tract infection (bUTI), because bUTI is a serious infection that requires prompt diagnosis and antibiotic therapy. Escherichia coli is the most common and important uropathogen. The objective of our study was to characterize the clinical presentation of E coli bUTI.

Methods

Retrospective cohort study of consecutive adult patients admitted for community acquired E. coli bacteremia from January 1, 2015 to December 31, 2016 was conducted at 4 acute care academic and community hospitals in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Logistic regression models were developed to identify E coli bUTI cases without urinary symptoms.

Results

Of 462 patients with E. coli bacteremia, 284 (61.5%) patients had a urinary source. Of these 284 patients, 161 (56.7%) had urinary symptoms. In a multivariable model, bUTI without urinary symptoms were associated with older age (age < 65 years as reference, age 65–74 years had OR of 2.13 95% CI 0.99–4.59 p = 0.0523; age 75–84 years had OR of 1.80 95% CI 0.91–3.57 p = 0.0914; age > =85 years had OR of 2.95 95% CI 1.44–6.18 p = 0.0036) and delirium (OR of 2.12 95% CI 1.13–4.03 p = 0.0207). Sepsis by SIRS criteria was present in 274 (96.5%) of all bUTI cases and 119 (96.8%) of bUTI cases without urinary symptoms.

Conclusion

The majority of patients with E. coli bacteremia had a urinary source. A significant proportion of bUTI cases had no urinary symptoms elicited on history. Elderly and delirious patients were more likely to have bUTI without urinary symptoms. In elderly and delirious patients with sepsis by SIRS criteria but without a clear infectious source, clinicians should suspect, investigate, and treat for bUTI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Expert consensus and stewardship interventions emphasize treatment of bacteriuria based on urinary symptoms [1,2,3,4]. However, clinicians often diagnose and treat elderly patients for urinary tract infection (UTI) when they have only non-specific symptoms such as delirium based on the belief that elderly patients with UTI may present without localizing symptoms [5,6,7]. This raises uncertainty as to what constitutes symptoms of UTI, what is asymptomatic bacteriuria, and whether it warrants treatment. Hereafter, we use the term asymptomatic bacteriuria to signify bacteriuria without any urinary symptoms.

Bacteriuria with bacteremia is a true infection requiring treatment, so it can be used to guide diagnostic criteria for UTI. Diagnostic criteria for UTI should capture all bacteremic UTI (bUTI), because it is associated with a higher mortality rate [8, 9]. Prior studies suggested that elderly patients with bUTI often do not have urinary symptoms [10,11,12], which is recognized by Centre of Disease Control as “asymptomatic bacteremic urinary tract infection” [13]. However, prior studies do not provide alternative clinical features to reliably capture bUTI [10,11,12].

Approximately 20–30% of patients presenting to emergency department with febrile or complicated UTI or pyelonephritis have bacteremia [14,15,16]. Escherichia coli is the most important pathogen for UTI and accounts for over 70% of all cases [17, 18]. In patients admitted to hospital with E coli bacteriuria who had a blood culture done, approximately 15% of patients had E coli bacteremia [19].

We conducted a study on E. coli bUTI patients to characterize the proportion of and risk factors for bUTI without urinary symptoms. We also aimed to find clinical features that would be sensitive enough to capture bUTI cases without urinary symptoms.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a retrospective cohort study at 4 acute care academic and community hospitals in the Greater Toronto Area. Research ethics board approval was obtained from each institution.

The study included consecutive adult patients admitted to the hospital for community acquired E. coli bacteremia from January 1, 2015 to December 31, 2016. Community acquired bacteremia was defined by positive blood culture collected at admission or within 48 h of hospital admission. E. coli bacteremia was defined as at least 1 positive blood culture for E. coli. Patients were excluded if they had an unclear infectious focus. This group was likely composed of patients with urinary source as well as patients with non-urinary source. Analysis and comparison to this mixed patient population would be difficult to interpret.

Data collection

Data were obtained from electronic and paper medical records at each hospital site and entered into a standardized case report form. Data on demographics, comorbidities, clinical presentation, investigations, microbiological data, investigations, surgical interventions, antibiotic therapy and clinical outcomes were collected. A second auditor performed sample reliability checks on 10% of the population.

Variable definitions

Comorbidities were entered as per Charlson comorbidity index [20].

Urinary source (i.e. bUTI) required a urine culture with significant monomicrobial growth of E. coli > =10 × 10^6 CFU/L and any of the following criteria:

-

1)

Clinical urinary tract infection as per diagnostic criteria for treatment by Loeb et al. [21]. Patients were diagnosed with UTI based on dysuria or > =2 of the following: fever, urgency, flank pain, urinary incontinence, shaking chills, frequency, gross hematuria or suprapubic pain [21]. Patients with urinary catheter were diagnosed with UTI based on > = 1 of the following: new costovertebral tenderness, rigors, new onset delirium or fever [21].

-

2)

Imaging findings suggestive of pyelonephritis including perinephric stranding or hydronephrosis with flank pain or costovertebral angle (CVA) tenderness

-

3)

Recent urologic procedure (including ureteric stenting, cystoscopy, prostate biopsy) with no other clear source

-

4)

Monomicrobial growth of E. coli in blood and urine culture with the same susceptibility pattern and no other obvious source on clinical assessment

Biliary source was defined as any of the following:

-

1)

Evidence of cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis, or cholangitis on imaging

-

2)

Known cholecystostomy tube or biliary malignancy with no other obvious source

-

3)

Recent manipulation of biliary tree including ERCP with no other obvious source

Intra-abdominal source was defined as any of the following:

-

1)

Evidence of intra-abdominal abscess, appendicitis, diverticulitis, pancreatitis or mass on abdominal imaging

-

2)

Known intra-abdominal drain with no other obvious source

-

3)

Recent intra-abdominal surgery with no other obvious source

The above criteria were also checked for agreement with the main responsible physician’s diagnosis for accuracy. Other infectious foci including pneumonia were based on the clinician’s final diagnosis.

Urinary symptoms and signs were based on the clinician’s documentation on presentation. Urinary symptoms included dysuria, urinary urgency, urinary frequency, gross hematuria, flank pain, suprapubic pain and urinary retention. Urinary signs included suprapubic tenderness and costovertebral or flank tenderness. Hereafter, bUTI without urinary symptoms refer to bUTI without any of the aforementioned urinary symptoms or signs.

Patients were screened regularly by nurses and assessed by physicians for delirium based on the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) criteria [22]. Fever was defined as > 37.8C in elderly patients age > 65 [23] and > =38C in all other patients. Sepsis as per the SIRS [24] and qSOFA [25] score were calculated for all patients.

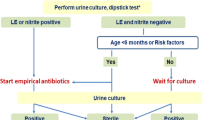

Urinalysis was done using urine test strips.

History of prior UTI was based on patient reporting, as documented in the patient chart by the main responsible physician.

Outcomes

Patients were followed until death in hospital or discharge. Length of stay was calculated from time of blood culture collection to discharge or death in hospital.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons between two groups were done with Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-normally distributed continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

Diagnostic properties were determined for clinical factors as the test and urinary source as criterion standard. For example, if dysuria was the test, then a true positive was a patient who had dysuria and bUTI. A true negative was a patient who did not have dysuria and had a non-urinary source for the E. coli bacteremia. A false positive was a patient who had dysuria and a non-urinary source for the E. coli bacteremia. A false negative was a patient who did not have dysuria, but had bUTI. We calculated sensitivity and specificity with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using the Wilson method. For likelihood ratios, we calculated the 95% CI according to the method described by Simel et al. [26].

In patients with bUTI, a univariate logistic regression model was done predicting bUTI without urinary symptoms. Potential predictors were selected a priori, which included age, gender, stroke, dementia, urinary risk factors, delirium, and severity of infection. Significant predictors were selected based on p < 0.2 from univariate analyses. A final multivariable logistic regression model of significant predictors was selected based on clinical judgment, p-value, full model with all predictors, as well as both forward and backward stepwise regression based on Akaike information criterion. Hospital site was forced as a predictor into this model.

There are < 5% missing data for all variables, so listwise deletion was done for analyses such as modeling.

All reported CI were 2-sided 95% intervals and all tests were 2-sided with a P < 0.05 significance level. All analyses were done with R version 3.6.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

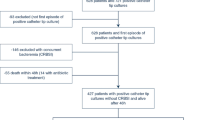

In total, 462 patients with E. coli bacteremia and a known infectious source were included in the analysis (Fig. 1). Of the 462 patients, 284 (61.5%) patients had a bUTI and 178 (38.5%) patients had a non-urinary source (Table 1). Baseline characteristics of patients with E coli bacteremia and an unclear source are described in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Urinary frequency had the highest positive likelihood ratio (PLR) of 7.6 (95% CI 3.1–18.7) for ruling in urinary source (Table 2). Other urinary symptoms and signs have PLR ranging from 1.4 to 4.4 and negative likelihood ratio (NLR) ranging from 0.81 to 0.99. On clinical assessment, no urinary symptoms and signs had a NLR of 0.56 (95% CI 0.48–0.66). Negative leukocytes and nitrites on urinalysis had the lowest NLR of 0.18 (95% CI 0.11–0.28) for ruling out a urinary source.

Of the 284 patients with bUTI, 123 (43.3%) had no urinary symptoms (Table 3). Fever and/or urinary symptoms were present in 244 (85.9%) patients with bUTI. In the univariate analysis, potential significant predictors of bUTI without urinary symptoms included age, dementia, benign prostate hypertrophy, prior UTI, nephrolithiasis, delirium, sepsis by qSOFA criteria, and hypotensive shock (Additional file 1: Table S2). In the final multivariable model, significant predictors included only age, delirium and prior UTI (Table 4, Additional file 1: Table S3). With increasing age, the proportion of patients with delirium and bUTI without urinary symptoms also increased (Additional file 1: Table S4).

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study of patients with E. coli bacteremia showed that the majority of patients (61.5%) had a urinary source. A significant proportion of patients (43.3%) with bUTI did not have any urinary symptoms or signs elicited on history or physical exam especially in context of older age and delirium. Even the inclusion of fever and/or urinary symptoms would miss approximately 1 in 7 bUTIs. Sepsis by SIRS criteria was present in almost all of the bUTI cases without urinary symptoms.

We used a comparison group of non-urinary source E. coli bacteremia patients. The majority of these patients had intra-abdominal or hepato-biliary infection, similar to prior studies [27, 28]. Patients with a non-urinary source had similar outcomes including mortality compared to patients with urinary source. We believe this is an appropriate comparison group as it simulates a common scenario whereby a patient presents with sepsis or E. coli bacteremia of unknown source, and the clinician must evaluate and determine the source of infection.

Our finding of a significant proportion of bUTI presenting without urinary symptoms in elderly patients is consistent with prior studies on bUTI [11, 12] and non-bacteremic UTI [29]. Although our study found urinary frequency to be useful for ruling in UTI, it demonstrated little diagnostic utility in a systematic review of observational studies [29]. This may be due to the wide variation in the case definition of UTI that includes asymptomatic bacteriuria without true infection. The usefulness of urinalysis in ruling out UTI in our study was similarly found in prior studies with a reported high sensitivity [30] and negative predictive value [31].

There are several reasons why an elderly patient with delirium and a UTI may have no urinary symptoms. Frail adults may have atypical presentation of infections [6, 32]. Even if such patients experience UTI symptoms, they may not be able to describe or demonstrate them due to cognitive dysfunction [6]. While clinical evaluation for typical urinary symptoms and signs were not sensitive to capture all bUTI, sepsis by SIRS criteria came close. The qSOFA components such as altered mental status and tachypnea tend to be non-specific for infection in elderly patients [33, 34]. This may lead to overtreatment and missed diagnosis of delirium causes other than infection [8]. In our study, qSOFA was not sensitive for bUTI, being positive in only 38.7% of all bUTI patients and 46.3% of bUTI patients without urinary symptoms. In contrast, SIRS criteria have been shown previously to be sensitive in identifying bacteremia in all patients [35] including elderly patients in particular [33]. Therefore, physicians may continue to use SIRS criteria for decisions on when to draw blood cultures, especially in elderly patients.

This study has several strengths. It included a large population of 284 bUTI cases compared to prior studies that ranged from 61 to 191 patients [10,11,12]. It was conducted across academic and community hospitals, which increases its generalizability. Also, by limiting inclusion to those patients with bacteremia, it allows characterization of UTI without urinary symptoms and largely eliminates the inclusion of asymptomatic bacteriuria without true infection.

Our study has limitations that merit discussion. First, there are the inherent limitations from a retrospective chart review. However, the data collection was rigorous and a second auditor had performed sample data checking to ensure completeness and quality. The clinical assessment of patients for urinary symptoms and signs were not standardized and may vary between clinicians. Almost all patients in our study had sepsis as per SIRS or qSOFA criteria, and had a blood culture drawn at presentation. Therefore, all patients should have undergone a systematic evaluation for possible infectious foci including UTI. As well, the non-standardized approach reflects real world settings. Second, there may be ascertainment bias. The study could only capture patients in whom blood cultures were drawn. Physicians may be more likely to order blood cultures for patients in whom the symptoms are non-specific or the infectious source is uncertain. The study also likely selected sicker patients with higher suspicion for bacteremia. This could lead to overestimation of the diagnostic properties but does not affect our most important findings: that UTI is the most common cause of E. coli bacteremia, and most elderly or delirious patients had bUTI without urinary symptoms. Third, our study captured bUTI by E. coli only, so it would be an extrapolation to all bUTI. Nonetheless, E coli is the most common and important pathogen responsible for approximately 70% of pyelonephritis [17]. Fourth, UTI presentation may be different and unique in patients with spinal cord injury or disease. Unfortunately, our study did not collect information on spinal cord injury or disease. It is likely that many of these patients would have been captured in the variable of chronic indwelling Foley catheter.

These findings offer insight in the clinical presentation of E coli bUTI. Urinary symptoms are useful to diagnose UTI. However, elderly and/or delirious patients may have a bUTI despite having no urinary symptoms or signs elicited on history or exam. For these cases, in addition to symptoms and signs, SIRS criteria and positive urinalysis without any other clear infectious source may be important clues to a bUTI that require antibiotic therapy. Our study should be interpreted with caution and not be extrapolated to E coli bacteriuria without bacteremia. This is outside the scope of our study. Thus, our study does not address which patients are at risk for bUTI. This should be explored in future studies.

Our study adds to the evidence that UTI without urinary symptoms is common and important in elderly and/or delirious patients. We hope that this study can contribute towards a meaningful update of the concept of UTI symptoms. Emphasis on urinary symptoms without consideration of other aspects of the patient’s presentation is potentially harmful and may miss bUTI. A more holistic approach would consider other clinical factors including age, delirium and sepsis by SIRS criteria. This approach may help increase the chance of antibiotics being given to those who truly need it.

Conclusions

Most of the patients with E. coli bacteremia had a urinary source. A significant proportion of bUTI cases had no urinary symptoms. Elderly and delirious patients were more likely to have bUTI without urinary symptoms. In these elderly and delirious patients who satisfied SIRS criteria but without a clear infectious source, clinicians should suspect, investigate, and treat for bUTI.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- UTI:

-

Urinary tract infection

- bUTI:

-

bacteremic urinary tract infection

References

Loeb M, Bentley DW, Bradley S, Crossley K, Garibaldi R, Gantz N, et al. Development of minimum criteria for the initiation of antibiotics in residents of long-term–care facilities: results of a consensus conference. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2001;22:120–4.

Nicolle LE, Gupta K, Bradley SF, Colgan R, DeMuri GP, Drekonja D, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of asymptomatic bacteriuria: 2019 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:e83–110.

Daniel M, Keller S, Mozafarihashjin M, Pahwa A, Soong C. An implementation guide to reducing overtreatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:271–6.

Leis JA, Rebick GW, Daneman N, Gold WL, Poutanen SM, Lo P, et al. Reducing antimicrobial therapy for asymptomatic bacteriuria among noncatheterized inpatients: a proof-of-concept study. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:980–3.

Petty LA, Vaughn VM, Flanders SA, Malani AN, Conlon A, Kaye KS, et al. Risk factors and outcomes associated with treatment of asymptomatic Bacteriuria in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1519–27.

D’Agata ED, Loeb MB, Mitchell SL. Challenges in assessing nursing home residents with advanced dementia for suspected urinary tract infections. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:62–6.

Juthani-Mehta M, Drickamer MA, Towle V, Zhang Y, Tinetti ME, Quagliarello VJ. Nursing home practitioner survey of diagnostic criteria for urinary tract infections. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1986–90.

Finucane TE. “Urinary tract infection”—requiem for a heavyweight. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:1650–5.

Woodford HJ, George J. Diagnosis and management of urinary tract infection in hospitalized older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:107–14.

Tal S, Guller V, Levi S, Bardenstein R, Berger D, Gurevich I, et al. Profile and prognosis of febrile elderly patients with bacteremic urinary tract infection. J Inf Secur. 2005;50:296–305.

Woodford H, Graham C, Meda M, Miciuleviciene J. Bacteremic urinary tract infection in hospitalized older patients—are any currently available diagnostic criteria sensitive enough? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:567–8.

Barkham TM, Martin FC, Eykyn SJ. Delay in the diagnosis of bacteraemic urinary tract infection in elderly patients. Age Ageing. 1996;25:130–2.

CDC. Health-associated Infection Surveillance Protocol for Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) Events for Long-term Care Facilities. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/PDFs/LTC/LTCF-UTI-protocol-current.pdf. Accessed 14, Dec 2019.

Van Nieuwkoop C, Hoppe BP, Bonten TN, van’t Wout JW, Aarts NJ, Mertens BJ, et al. Predicting the need for radiologic imaging in adults with febrile urinary tract infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:1266–72.

Chen Y, Nitzan O, Saliba W, Chazan B, Colodner R, Raz R. Are blood cultures necessary in the management of women with complicated pyelonephritis? J Inf Secur. 2006;53:235–40.

Spoorenberg V, Prins JM, Opmeer BC, de Reijke TM, Hulscher ME, Geerlings SE. The additional value of blood cultures in patients with complicated urinary tract infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:O476–9.

Czaja CA, Scholes D, Hooton TM, Stamm WE. Population-based epidemiologic analysis of acute pyelonephritis. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:273–80.

Echols RM, Tosiello RL, Haverstock DC, Tice AD. Demographic, clinical, and treatment parameters influencing the outcome of acute cystitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:113–9.

Marschall J, Zhang L, Foxman B, Warren DK, Henderson JP. Both host and pathogen factors predispose to Escherichia coli urinary-source bacteremia in hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:1692–8.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83.

Loeb M, Brazil K, Lohfeld L, McGeer A, Simor A, Stevenson K, et al. Effect of a multifaceted intervention on number of antimicrobial prescriptions for suspected urinary tract infections in residents of nursing homes: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2005;331:669.

Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method: a new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:941–8.

High KP, Bradley SF, Gravenstein S, Mehr DR, Quagliarello VJ, Richards C, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation of fever and infection in older adult residents of long-term care facilities: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:149–71.

American College of Chest Physicians, Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference Committee. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:864–74.

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315:801–10.

Simel DL, Samsa GP, Matchar DB. Likelihood ratios with confidence: sample size estimation for diagnostic test studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44:763–70.

Harris PN, Tambyah PA, Lye DC, Mo Y, Lee TH, Yilmaz M, et al. Effect of piperacillin-tazobactam vs meropenem on 30-day mortality for patients with E coli or Klebsiella pneumonia bloodstream infection and ceftriaxone resistance: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:984–94.

Peralta G, Sanchez MB, Garrido JC, De Benito I, Cano ME, Martínez-Martínez L, et al. Impact of antibiotic resistance and of adequate empirical antibiotic treatment in the prognosis of patients with Escherichia coli bacteraemia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:855–63.

Gbinigie OA, Ordóñez-Mena JM, Fanshawe TR, Plüddemann A, Heneghan C. Diagnostic value of symptoms and signs for identifying urinary tract infection in older adult outpatients: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Inf Secur. 2018;77:379–90.

Shimoni Z, Glick J, Hermush V, Froom P. Sensitivity of the dipstick in detecting bacteremic urinary tract infections in elderly hospitalized patients. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0187381.

Juthani-Mehta M, Tinetti M, Perrelli E, Towle V, Quagliarello V. Role of dipstick testing in the evaluation of urinary tract infection in nursing home residents. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:889–91.

Resnick NM, Marcantonio ER. How should clinical care of the aged differ? Lancet. 1997;350:1157–8.

Chou HL, Han ST, Yeh CF, Tzeng IS, Hsieh TH, Wu CC, Kuan JT, Chen KF. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome is more associated with bacteremia in elderly patients with suspected sepsis in emergency departments. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e5634.

Pfitzenmeyer P, Decrey H, Auckenthaler R, Michel JP. Predicting bacteremia in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:230–5.

Coburn B, Morris AM, Tomlinson G, Detsky AS. Does this adult patient with suspected bacteremia require blood cultures? JAMA. 2012;308:502–11.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Sarwat Abbasi, Deborah Somanader and Sheetal Vajaria, who helped with extracting patient data into the database and organizing the data.

Funding

The PSI (The Physicians’ Services Inc.) Foundation Resident Research Grant funded this project. The funding body did not have any role in study design, data collection, analysis, data interpretation or manuscript writing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MJB and AMM conceived and designed the study. MJB and ST oversaw data collection. ADB performed the statistical analysis and wrote a first draft of the manuscript. ADB, MJB, ST, CMB and AMM reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Research ethics board approval was obtained from Mount Sinai Hospital Research Ethics Board (reference number 16–0129-C) and University Health Network Research Ethics Board (reference number 16–5446). As a retrospective study that reports de-identified data, patients’ consent for participation was waived.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics of E. coli bacteremic patients with urinary source, non-urinary source and unclear source. Table S2. Univariate logistic regression model predicting bUTI without urinary symptoms. Table S3. Multivariable logistic regression model predicting bUTI without urinary symptoms. Table S4. Proportion of delirium and UTI without urinary symptoms in different age categories in patients with bUTI.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bai, A.D., Bonares, M.J., Thrall, S. et al. Presence of urinary symptoms in bacteremic urinary tract infection: a retrospective cohort study of Escherichia coli bacteremia. BMC Infect Dis 20, 781 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05499-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05499-1