Abstract

Background

South Africa has the highest HIV prevalence and supports the largest antiretroviral therapy (ART) programme globally. With the introduction of a test and treat policy, ensuring long term optimal adherence to ART (≥95%) is essential for successful patient and public health outcomes. The aim of this study was to assess long-term ART adherence to inform best practices for chronic HIV care.

Method

Long-term ART adherence was retrospectively analysed over a median duration of 5 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 5.3–6.5) in patients initially enrolled in a randomised controlled trial assessing tuberculosis and HIV treatment integration and subsequently followed post-trial in an observational cohort study in Durban, South Africa. The association between baseline patient characteristics and adherence over time was estimated using generalized estimating equations (GEE). Adherence was assessed using pharmacy pill counts conducted at each study visit and compared to 6 monthly viral load measurements. A Kaplan Meier survival analysis was used to estimate time to treatment failure. The McNemar test (with exact p-values) was used to determine the effect of pill burden and concurrent ART and tuberculosis treatment on adherence.

Results

Of the 270 patients included in the analysis; 54.8% were female, median age was 34 years (IQR:29–40) and median time on ART was 70 months (IQR = 64–78). Mean adherence was ≥95% for each year on ART. Stable patients provided with an extended 3-month ART supply maintained adherence > 99%. At study end, 96 and 94% of patients were optimally adherent and virologically suppressed, respectively. Time since ART initiation, female gender and primary breadwinner status were significantly associated with ≥95% adherence to ART. The cumulative probability of treatment failure was 10.7% at 5 years after ART initiation. Concurrent ART and tuberculosis treatment, or switching to a second line ART regimen with higher pill burden, did not impair ART adherence.

Conclusion

Optimal long-term adherence with successful treatment outcomes are possible within a structured ART programme with close adherence monitoring. This adherence support approach is relevant to a resource limited setting adopting a test and treat strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Currently, an estimated 36.7 million people are living with HIV (PLWH) worldwide [1]. South Africa has the highest adult HIV prevalence (18%) in sub-Saharan Africa and the largest adult population of PLWH in the world, estimated at approximately 7.5 million people [2, 3]. In September 2016, universal test and treat policy was incorporated into the South African national antiretroviral therapy (ART) guidelines and the country’s government funded national antiretroviral (ARV) programme is now the largest globally, providing HIV care and ART to over 4 million people [4, 5].

Access to ART is only one aspect of an effective HIV management programme. Optimal adherence to ART is essential and early studies reported that ≥95% adherence to ART was required to achieve and maintain viral suppression [6, 7]. Although recent studies have shown that virologic suppression may still be achieved with < 95% adherence levels, this is dependent on the ART regimen, duration of treatment and previous ART exposure [8, 9]. Furthermore, repeated adherence levels of < 100% and treatment interruptions are associated with an increased risk of nucleoside reverse transcriptase (NRTI) and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase (NNRTI) resistance which form the backbone of current first line ART regimens in South Africa [10,11,12]. Poor adherence may lead to a number of adverse consequences on both individual and public HIV healthcare. Firstly, poorly adherent patients who acquire resistance to first line NNRTI-based regimens are switched to second and third line ARV regimens which are costlier, have a higher pill burden, increased dosing frequency and often have less tolerable side effects [13, 14]. Access to second line, third line and salvage treatment regimens are also limited or may be unavailable in developing countries [15]. Secondly, resistant HIV strains can be transmitted to others resulting in primary resistance to first line treatment regimens in newly infected ART-naïve patients or acquired resistance in infected patients already on ART [16, 17]. Thirdly, treatment failure due to non-adherence is associated with a greater risk of progression to Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) and mortality [18, 19]. In addition, hospital admissions due to HIV disease progression and opportunistic infections further add to the burden of public health costs in resource limited countries [20, 21]. Thus, it is still recommended that ≥95% adherence be maintained to achieve optimal viral suppression and prevent HIV resistance [22, 23].

Short term ART adherence rates (less than 2 years from treatment initiation) in South African patients from multiple urban HIV clinics is reported to range from 63 to 88% [24,25,26,27], however, there is a paucity of information on long-term adherence in this population. As ART access continues to expand with the implementation of test and treat, our public health facilities face the challenge of retaining an increasing number of PLWH in life time care with limited healthcare budgets and insufficient human resources [28]. Initial studies in African test and treat patient cohorts have reported > 80% adherence levels in the first year post-ART initiation [29, 30]. Monitoring and determining long term adherence patterns can provide insight into observed treatment outcomes and assist in developing adherence support and intervention strategies that would be relevant to resource-constrained countries implementing a test and treat policy.

Methods

Study aim, setting and design

The aim of this cohort study was to assess long-term adherence in a cohort of patients on ART for at least 5 years at the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa’s (CAPRISA) eThekwini Clinical Research site in Durban, South Africa.

Initially, HIV and tuberculosis (TB) co-infected patients were enrolled in the Starting Antiretroviral Therapy at Three Points in Tuberculosis (SAPiT) open label randomised controlled trial from June 2005 to July 2008 (n = 642). Details of the study outcomes have been published elsewhere [31, 32]. Baseline demographic data, including age, gender, education and socio-economic variables were obtained at enrolment. Study patients were initiated on a once daily, weight-based ART regimen containing efavirenz (EFV) or nevirapine (NVP) plus lamivudine (3TC) and enteric coated didanosine (ddI) either during or after completion of tuberculosis treatment. Viral load (Cobas® Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor, version 1.5, Roche) and CD4+ cell count (Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur™) measurements were conducted at screening, on randomization into the study and 6 monthly thereafter.

After completion of follow up in the SAPiT trial, patients were offered enrolment into a prospective observational study, TB Recurrence upon Treatment with HAART (TRuTH), investigating the rate of TB recurrence in HIV infected adults on ART who had completed pulmonary TB treatment (n = 402) [33, 34]. Viral load (Cobas® Ampliprep-Roche TaqMan®) and CD4+ cell count (Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur™) measurements were performed at least 6 monthly in the study. In 2011, ddI was replaced by tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) in viral suppressed patients in line with World Health Organisation (WHO) recommendations at the time [35]. Patients were enrolled into the TRuTH observational study from November 2009 to July 2011 and follow up was completed in 2014.

All patients received pre-ART education and ongoing adherence support counselling by trained counsellors and site pharmacists post-ART initiation. Pillboxes were provided to all patients as an adherence aid. Patients who did not come in on their scheduled clinic appointment date were telephonically or physically contacted. Close family members or friends were enlisted as treatment supporters, where possible, to provide additional social support for patients identified with adherence challenges.

The SAPiT and TRuTH studies were conducted under the oversight of the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (BREC) at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (BREC ref.: E107/05 [SAPiT]; BF051/09 [TRuTH]). Participants in the SAPiT and TRuTH studies provided written informed consent. The current study is a retrospective secondary analysis of previously collected anonymized data from the parent trials with no direct participant contact (BREC ref.: BE046/16).

To assess long-term adherence, we conducted a retrospective analysis in a sub-cohort of patients on ART for at least 5 years from the time of ART initiation in the SAPiT trial until completion of follow up in the TRuTH study. To maintain continuity of care, patients accessed ART via the CAPRISA AIDS Treatment (CAT) programme at the same clinic after completion of follow up in SAPiT and before enrolment in TRuTH. Patients who never initiated ART, were lost to follow up in the SAPiT trial, did not receive ART from the site’s research pharmacy and for whom pill count data was missing for more than 6 consecutive months in either study were excluded.

Long-term adherence assessment

Adherence to ART in both studies were determined from pharmacy pill count data and viral load measurements. Pill counts were conducted by the study pharmacist at monthly study visits in the SAPiT trial and at monthly or 3-monthly study visits in the TRuTH study. Adherence percentage was calculated using the following formula [36]:

Optimal adherence was defined as ≥95% of doses taken in the time between the study visits [7]. Pill count data was not available for ART that was dispensed in the CAT programme (time period between exit form SAPiT study and enrolment into TRuTH study). Pill count adherence was not assessed for visits where there was a clinician-initiated treatment interruption or where pill count data was missing.

Statistical analysis

Baseline demographic data were analyzed by descriptive statistics and reported as median with inter-quartile range (IQR) or proportions. Undetectable viral load was defined as < 400 copies/mL as per the South African national treatment guidelines at the time. In the SAPiT trial, treatment failure was defined as two HIV-1 RNA measurements of > 1000 copies/mL taken at least 4 weeks apart followed by ART discontinuation or change of all drugs in the ARV regimen. In the TRuTH study treatment failure was defined as two consecutive HIV-1 RNA measurement of > 1000 copies/mL at least 6 months apart followed by a change to a second line boosted lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r) based regimen.

Mean pill count adherence was calculated as the weighted mean of the monthly and/or 3-monthly adherence values over that time period, where the weights were calculated as the length of time between each study visit. The association between baseline patient characteristics and adherence over time was estimated using generalized estimating equations (GEE) with a logit-link function and exchangeable working correlation structure. A univariable analysis was first performed, and thereafter a multivariable model was estimated with gender, age and factors with a p-value < 0.2 in the unadjusted analyses. Interaction terms were incorporated into the multivariable model, one at a time, and were retained if found to be significant. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) (and associated 95% confidence intervals [95% CI]) were calculated to assess the extent to which mean pill count adherence (< 95% vs ≥95%) for each year on ART could be used to predict viral load outcomes (< 400 copies/mL vs ≥400 copies/mL) at the end of the same 12 month period. The McNemar test (with exact p-values) was used to determine the impact of concurrent ART and TB treatment on adherence to ART by analyzing changes in ART adherence and viral load suppression rates before and during TB treatment. The McNemar test was also applied to the adherence proportions and viral load suppression rates before and after switching to a second line regimen to assess the impact of the pill burden on adherence. A Kaplan Meier survival analysis was used to estimate time to treatment failure. All statistical tests were conducted at 5% level of significance. Statistical Analysis System (SAS) version 9.4 software was used to conduct statistical analysis.

Results

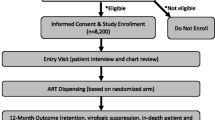

A total of 270 patients met the inclusion criteria for this analysis (Fig. 1). The median age was 34 years (IQR:29–40) and 54.8% were female (Table 1). At ART initiation the median CD4+ cell count was 145 cells/mm3 (IQR:76–249) and median viral load was 141,000 copies/mL (IQR:37757–386,000). Most patients (254/270) were classified as WHO stage 3 at baseline. A third of the cohort had completed secondary school, 60% were in full or part-time employment and more than half of all patients had disclosed their HIV status. The median duration on ART from initiation to completion of follow up was 70 months (IQR: 64–78).

The time period between patient exit from SAPiT and enrolment in TRuTH (where no pill count data available) was a median of 13 months (IQR: 5–21). The number of patients for whom pill count data was available in each 6 month period is shown in Table 2. Mean adherence was ≥95% for each year on ART. The majority of the cohort (94.8%) had an overall mean ART adherence of ≥95%. Of the 14 patients with sub-optimal adherence, nine had adherence estimates in the 90–95% range, two in the 80–90% range, two in the 70–80% range, and only one had less than 70% adherence. Mean adherence peaked (99.3%) at 18–24 months after ART initiation and remained above 98% from 32 months onward.

In the 6 months post-ART initiation, 91.8% of patients had optimal adherence. Half of all patients had at least one sub-optimal adherence measurement (< 95%) in the first 6 months after starting ART, less than 20% between the first and sixth year and 23% after 6 years on ART (Fig. 2). In the TRuTH study, patients with optimal adherence by pill count and an undetectable viral load (n = 267) were provided with an extended 3-month ART supply at a total of 1061 study visits. Overall mean adherence for patients who received a 3-month ART package was 99.5%.

Patient variables included in the univariable and multivariable GEE analyses are shown in Table 3. In the multivariable model, time since ART initiation (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] =1.10; 95%CI: 1.05–1.16), female gender (aOR = 1.33, 95%CI:1.05–1.67) and being a primary breadwinner (aOR = 1.32, 95%CI 1.02–1.72) were significantly associated with achieving optimal adherence.

Viral suppression rates were 87.4% 6 months after ART initiation and thereafter increased and remained above 92% throughout follow up (Fig. 2). Eleven patients had a viral load > 400 copies/mL after 5 years and 94% of patients were virologically suppressed at the end of the follow up period. Pill count showed high sensitivity in predicting viral suppression but had poor specificity when the viral load was detectable (Table 4).

Thirty-three patients experienced treatment failure with approximately half of all treatment failures (n = 17) occurred within 2 years after ART initiation. The cumulative probability of treatment failure was 10.7% at 5 years after ART initiation (Fig. 3). Adherence and viral load measurements prior to and after switching to a second line boosted LPV/r regimen was available for 21 of the treatment failure patients. The number of patients with optimal adherence improved and there was a significant increase in viral load suppression at 6 and 12 months after switching to the second line regimen (Table 5).

Of the 21 patients diagnosed and initiated on treatment for recurrent TB in the TRuTH study, three exited the study whilst on TB treatment and one did not complete their course of TB treatment. In the remaining 17 patients, there was a decline in optimal adherence and viral load suppression when patients were on both ART and TB treatment, but this was not statistically significant (Table 5).

Discussion

Our study found overall high adherence to ART, determined by pill count, in this South African cohort followed up over a period of more than 5 years. Treatment outcomes were successful on first and second line treatment regimens, with 93.9% of patients virologically suppressed at study completion and only 12% experiencing treatment failure over the entire study period. The likelihood of achieving optimal adherence also improved with time on ART. Adherence during the first year of treatment was higher (98%) than those reported in several African studies, where adherence estimates ranged from 72 to 94% [25, 37,38,39,40,41]. Over the long term, mean adherence was maintained ≥95% for each year of follow up. Long-term adherence studies in Botswana, Senegal and Nigeria also found comparably high adherence levels [42,43,44,45]. Intensive pre-ART education and counselling sessions, an ongoing adherence support programme post-ART initiation, provision of pillboxes and use of a once-daily ART regimen, support measures that have been shown to assist adherence, may have played a role in helping to attain high adherence [46,47,48,49]. Additionally, enteric coated ddI was used instead of stavudine (D4T) in our first line ART regimen due its better side-effect profile, thereby avoiding non-adherence and discontinuation associated with stavudine toxicity observed elsewhere [50, 51].

Female patients were 33% more likely to have optimal adherence compared to males in our cohort. Although gender has not been consistently found to influence ART adherence, HIV infected women in developing countries tend to demonstrate better health seeking behaviours than men which may be motivated by their role as the primary care giver in their families [52, 53]. Being a primary breadwinner was also positively associated with optimal adherence which could indicate that the responsibility of being the main income earner may have been an adherence facilitator in this group of patients.

Viral suppression rates exceeded 90% for each year throughout the observation period. Similar long-term virologic outcomes have been reported in other low- and middle-income regions [51, 54,55,56,57,58]. The proportion of patients failing treatment was highest in the 2 years after ART initiation, thereafter, the number of treatment failures declined with each subsequent year on ART. Interestingly, non-adherence by pill count was most frequent in the first 6 months of ART in our cohort. Poor adherence in the initial months after ART initiation has been shown to increase the risk of virologic failure in later years and these early adherence lapses may be the reason for the higher number of treatment failures initially observed thus highlighting the importance of prioritizing adherence monitoring and support interventions to ensure optimal adherence from ART initiation [25, 44, 59,60,61].

Sensitivity was high, but specificity was low for the use of pill count data as a proxy for viral load outcomes. Whilst some studies have demonstrated an association between pharmacy adherence measures and virologic outcomes others have found poor agreement between the two measures [39, 40, 62,63,64,65]. We used an adherence threshold of ≥95%, however, viral suppression has been reported in patients with 85–94% adherence on long-term ART [66]. Furthermore, while pill counts provide a more objective method of adherence assessment, patient manipulation is possible as non-adherent patients may discard or leave behind medication not taken and return the desired number of pills to demonstrate good adherence [67, 68]. Although plasma viral suppression is possible with sub-optimal adherence, low-level viral replication continues in the plasma and reservoirs such as the central nervous system and genital tract, the long-term effects of which have not been fully elucidated [8, 69]. Therefore, high adherence to ART remains essential to ensuring the best clinical outcomes.

Patients who were provided with an extended 3-month ART supply in the TRuTH study were able to maintain high adherence levels over the extended time between clinic visits. This finding provides reassurance that stable patients can maintain optimal adherence when provided with an extended ART supply and patients who successfully adhere to treatment in the first 2 years are ideal candidates for more than 1 month’s supply of treatment. In an overburdened public health care setting, such as South Africa, this practice can ease clinic patient load and reduce the need for monthly clinic visits which impact negatively on patient finances and employment prospects.

High pill burden, regimen complexity and dosing more than once a day are known to hinder adherence [70]. Despite the additional pill burden and dosing frequency with switching from a once daily NNRTI-based regimen to a twice daily LPV/r regimen, with almost double the number of pills to be taken, adherence was not impaired and viral load suppression improved significantly in our patients who failed first-line treatment. The use of a boosted LPV/r regimen, provision of enhanced adherence counselling to patients on the implications of treatment failure with reinforcement of the importance of good adherence and enlisting a treatment supporter, where possible, may account for the improved outcomes [71,72,73].

HIV and TB co-infection rates are highest in South Africa [74]. Concurrent treatment of both diseases reduces morbidity and mortality; however, patients must cope with the additional pill burden and overlapping side effects when taking ART and TB treatment which can lead to impaired or selective adherence to either ART or TB medication [32, 75, 76]. We found no significant changes in ART adherence or viral suppression in our patients on concurrent ART and TB treatment. This is commensurate with findings from other South African studies [77].

There are several limitations to our study. This was a retrospective study of ART adherence conducted at a single research site and adherence behaviour may have been influenced by participation in a clinical trial, where patients were routinely monitored and received extensive adherence support and counselling. Factors associated with adherence behaviour were limited to available baseline patient and clinical data. In addition, our patients were initiated on ART at lower CD4 counts with advanced HIV disease and sicker patients may be more motivated to adhere to treatment [78]. Hence, adherence in this cohort may not be generalizable to a ‘test and treat’ or public health patient setting. Assessment of adherence by pill count may be prone to bias as non-adherent patients familiar with the pill count assessment may ‘count pills’ and return the required number of pills to show good adherence. An accurate adherence calculation is not possible for patients who did not bring any remaining pills back, reported lost pills and/or pills left at home. The exclusion of patients that were lost to follow up, patients with missing pill count data for more 6 consecutive months, and the lack of pill count data in the time period between the SAPiT and TRuTH studies, could have resulted in an overestimation of adherence in our cohort.

Optimal long-term adherence rates observed in this cohort support the evidence of high adherence reported in other long-term African patient cohorts. Pill count should not be used as a standalone measure of adherence as it was not a good predictor of viral failure and viral load measurement remains the benchmark for monitoring treatment response. However, adherence during the 6 months post-ART initiation period has been shown to impact long-term treatment outcomes and, per in-country treatment guidelines, viral load is only measured 6 months after ART initiation and thereafter annually. Therefore, we recommend adherence monitoring using pill count as a quick, simple adherence measure at each visit in this critical 6 month period to identify patients with early adherence challenges and allow for timeous intervention.

Provision of adherence support measures which may have assisted patient adherence included individual and group counselling, provision of pill boxes, treatment supporters and tracking of patients who missed their clinic appointment date. Pharmacists were also able to identify patients experiencing adherence challenges when conducting pill counts and could either provide or refer patients for appropriate adherence counselling. We also demonstrated that providing stable patients with a 3-month ART supply was feasible as optimal adherence was still maintained over this extended period. This has the potential to reduce clinic workloads and patient time and costs associated with monthly clinic visits and is currently being investigated further in a randomized control trial [79]. Several studies are currently being undertaken in sub-Saharan Africa to monitor long term treatment outcomes in tests and treat populations [80]. Further research on long term adherence and adherence support strategies in these test and treat cohorts would help to determine if these factors could support optimal long term adherence to ART.

Conclusion

In summary, our study found optimal long-term adherence with good treatment outcomes in a structured ART programme with close adherence monitoring and support. With the implementation of a test and treat policy and rapid scale up of ART provision, it is imperative that patient adherence is monitored early on from ART initiation and then continually assessed and supported, to ensure a successful ART programme in South Africa.

Availability of data and materials

The data for this study can be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 3TC:

-

Lamivudine

- AIDS:

-

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral therapy

- ARV:

-

Antiretroviral

- BREC:

-

Biomedical Research Ethics Committee

- CAPRISA:

-

Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa’s

- CAT:

-

CAPRISA AIDS Treatment

- D4T:

-

Stavudine

- ddI:

-

Didanosine

- EFV:

-

Efavirenz

- IQR:

-

Inter-quartile range

- LPV/r:

-

Lopinavir/ritonavir

- NNRTI:

-

Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase

- NRTI:

-

Nucleoside reverse transcriptase

- NVP:

-

Nevirapine

- PLWH:

-

People are living with HIV

- SAPiT:

-

Starting Antiretroviral Therapy at Three Points in Tuberculosis

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- TDF:

-

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate

- TRuTH:

-

TB Recurrence upon Treatment with HAART

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation

References

World Health Organization, Global Health Observatory (GHO) data, HIV/AIDS. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.home. Accessed 16 Oct 2018.

Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi L, Zuma K, Jooste S, Zungu N et al. South African national HIV prevalence, incidence and behaviour survey, 2012 Cape Town, HSRC Press 2014 http://www.hsrc.ac.za/uploads/pageContent/4565/SABSSM%20IV%20LEO%20final.pdf. Accessed 27 Jun 2017.

Statistics South Africa, statistical release mid-year population estimates 2018. www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022017.pdf. Accessed 29 Aug 2018.

Implementation of the universal test and treat strategy for HIV positive patients and differentiated care for stable patients. Department of Health Circular, Republic of South Africa dated 26 Aug 2016 http://www.sahivsoc.org/Files/22%208%2016%20Circular%20UTT%20%20%20Decongestion%20CCMT%20Directorate%20(2).pdf. Accessed 24 Jul 2018.

UNAIDS, Country factsheets South Africa. 2017. http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/southafrica. Accessed 30 Sep 2018.

Bangsberg DR, Hecht FM, Charlebois ED, Zolopa AR, Holodniy M, Sheiner L, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitors, HIV-1 viral load, and development of drug resistance in an indigent population. AIDS. 2000;14(4):357–66.

Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(1):21–30.

Ammassari A, Trotta MP, Shalev N, Marconi P, Antinori A. Beyond virological suppression: the role of adherence in the late HAART era. Antivir Ther. 2012;17:785–92.

Bangsberg DR. Less than 95% adherence to nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor therapy can lead to viral suppression. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(7):939–41.

Gardner EM, Hullsiek KH, Telzak EE, Sharma S, Peng G, Burman WJ, et al. Antiretroviral medication adherence and class- specific resistance in a large prospective clinical trial. AIDS. 2010;24(3):395–403.

Oyugi JH, Byakika-Tusiime J, Ragland K, Laeyendecker O, Mugerwa R, Kityo C, et al. Treatment interruptions predict resistance in HIV-positive individuals purchasing fixed-dose combination antiretroviral therapy in Kampala, Uganda. AIDS. 2007;21(8):965–71.

Haberer JE, Musinguzi N, Boum Y, Siedner MJ, Mocello AR, Hunt PW, et al. Duration of antiretroviral therapy adherence interruption is associated with risk of virologic rebound as determined by real-time adherence monitoring in rural Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;70(4):386–92.

Snedecor SJ, Khachatryan A, Nedrow K, Chambers R, Li C, Haider S, et al. The prevalence of transmitted resistance to first-generation non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and its potential economic impact in HIV-infected patients. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e72784.

Nachega JB, Leisegang R, Bishai D, Nguyen H, Hislop M, Cleary S, et al. Association of antiretroviral therapy adherence and health care costs. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(1):18–25.

Taiwo BO, Murphy R. Transmitted resistance: an overview and its potential relevance to the management of HIV-infected persons in resource-limited settings. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic). 2007;6(3):188–97.

Cambiano V, Bertagnolio S, Jordan MR, Lundgren JD, Phillips A. Transmission of drug resistant HIV and its potential impact on mortality and treatment outcomes in resource-limited settings. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(Suppl 2):S57–62.

Barth RE, Wensing AM, Tempelman HA, Moraba R, Schuurman R, Hoepelman AI. Rapid accumulation of nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-associated resistance: evidence of transmitted resistance in rural South Africa. AIDS. 2008;22(16):2210–2.

Bangsberg DR, Perry S, Charlebois ED, Clark RA, Roberston M, Zolopa AR, et al. Non-adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy predicts progression to AIDS. AIDS. 2001;15(9):1181–3.

Lima VD, Harrigan R, Bangsberg DR, Hogg RS, Gross R, Yip B, et al. The combined effect of modern highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens and adherence on mortality over time. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50(5):529–36.

Long LC, Fox MP, Sauls C, Evans D, Sanne I, Rosen SB. The high cost of HIV-positive inpatient care at an urban hospital in Johannesburg, South Africa. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0148546.

Meintjes G, Kerkhoff AD, Burton R, Schutz C, Boulle A, Van Wyk G, et al. HIV-related medical admissions to a South African district hospital remain frequent despite effective antiretroviral therapy scale-up. Medicine. 2015;94(50):e2269.

Martin M, Del Cacho E, Codina C, Tuset M, De Lazzari E, Mallolas J, et al. Relationship between adherence level, type of the antiretroviral regimen, and plasma HIV type 1 RNA viral load: a prospective cohort study. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2008;24(10):1263–8.

Bangsberg DR, Kroetz DL, Deeks SG. Adherence-resistance relationships to combination HIV antiretroviral therapy. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4(2):65–72.

El-Khatib Z, Ekstrom AM, Coovadia A, Abrams EJ, Petzold M, Katzenstein D, et al. Adherence and virologic suppression during the first 24 weeks on antiretroviral therapy among women in Johannesburg, South Africa - a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:88.

Ford N, Darder M, Spelman T, Maclean E, Mills E, Boulle A. Early adherence to antiretroviral medication as a predictor of long-term HIV virological suppression: five-year follow up of an observational cohort. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10460.

Maqutu D, Zewotir T, North D, Naidoo K, Grobler A. Factors affecting first-month adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive adults in South Africa. Afr J AIDS Res. 2010;9(2):117–24.

Orrell C, Bangsberg DR, Badri M, Wood R. Adherence is not a barrier to successful antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. AIDS. 2003;17(9):1369–75.

Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Buchan I, Orbinski J, Attaran A, Singh S, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa and North America: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;296(6):679–90.

Molemans M, Vernooij E, Dlamini N, Shabalala FS, Khan S, van Leth F, et al. Changes in disclosure, adherence and healthcare interactions after the introduction of immediate ART initiation: an analysis of patient experiences in Swaziland. Tropical Med Int Health. 2019;24(5):563–70.

Iwuji C, McGrath N, Calmy A, Dabis F, Pillay D, Newell ML, et al. Universal test and treat is not associated with sub-optimal antiretroviral therapy adherence in rural South Africa: the ANRS 12249 TasP trial. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(6):e25112.

Abdool Karim SS, Naidoo K, Grobler A, Padayatchi N, Baxter C, Gray A, et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral drugs during tuberculosis therapy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(8):697–706.

Abdool Karim SS, Naidoo K, Grobler A, Padayatchi N, Baxter C, Gray AL, et al. Integration of antiretroviral therapy with tuberculosis treatment. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(16):1492–501.

Sivro A, McKinnon LR, Yende-Zuma N, Gengiah S, Samsunder N, Abdool Karim SS, et al. Plasma cytokine predictors of tuberculosis recurrence in antiretroviral-treated human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals from Durban, South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(5):819–26.

Maharaj B, Gengiah TN, Yende-Zuma N, Gengiah S, Naidoo A, Naidoo K. Implementing isoniazid preventive therapy in a tuberculosis treatment-experienced cohort on ART. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21(5):537–43.

World Health Organization, Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents: recommendations for a public health approach: 2010 revision. www.who.int/hiv/pub/arv/adult2010/en/. Accessed 03 Jun 2018.

Lam WY, Fresco P. Medication adherence measures:an overview. Biomed Res Int. 2015. p. 12.

Unge C, Sodergard B, Marrone G, Thorson A, Lukhwaro A, Carter J, et al. Long-term adherence to antiretroviral treatment and program drop-out in a high-risk urban setting in sub-Saharan Africa: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13613.

Peltzer K, du Preez NF, Ramlagan S, Anderson J. Antiretroviral treatment adherence among HIV patients in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:111.

Muyingo SK, Walker AS, Reid A, Munderi P, Gibb DM, Ssali F, et al. Patterns of individual and population-level adherence to antiretroviral therapy and risk factors for poor adherence in the first year of the DART trial in Uganda and Zimbabwe. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;48(4):468–75.

San Lio MM, Carbini R, Germano P, Guidotti G, Mancinelli S, Magid NA, et al. Evaluating adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy with use of pill counts and viral load measurement in the drug resources enhancement against AIDS and malnutrition program in Mozambique. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(10):1609–16.

Czaicki NL, Holmes CB, Sikazwe I, Bolton C, Savory T, Wa Mwanza M, et al. Nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected patients in Zambia is concentrated among a minority of patients and is highly variable across clinics. AIDS. 2017;31(5):689–96.

Bastard M, Fall MB, Laniece I, Taverne B, Desclaux A, Ecochard R, et al. Revisiting long-term adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in Senegal using latent class analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57(1):55–61.

Etard JF, Laniece I, Fall MB, Cilote V, Blazejewski L, Diop K, et al. A 84-month follow up of adherence to HAART in a cohort of adult Senegalese patients. Tropical Med Int Health. 2007;12(10):1191–8.

Meloni ST, Chang CA, Eisen G, Jolayemi T, Banigbe B, Okonkwo PI, et al. Long-term outcomes on antiretroviral therapy in a large scale-up program in Nigeria. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0164030.

Bussmann H, Wester CW, Ndwapi N, Grundmann N, Gaolathe T, Puvimanasinghe J, et al. Five-year outcomes of initial patients treated in Botswana’s national antiretroviral treatment program. AIDS. 2008;22(17):2303–11.

van Loggerenberg F, Grant AD, Naidoo K, Murrman M, Gengiah S, Gengiah TN, et al. Individualised motivational counselling to enhance adherence to antiretroviral therapy is not superior to didactic counselling in south African patients: findings of the CAPRISA 058 randomised controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(1):145–56.

Mbuagbaw L, Sivaramalingam B, Navarro T, Hobson N, Keepanasseril A, Wilczynski NJ, et al. Interventions for enhancing adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART): a systematic review of high quality studies. AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2015;29(5):248–66.

Rueda S, Park-Wyllie LY, Bayoumi AM, Tynan AM, Antoniou TA, Rourke SB, et al. Patient support and education for promoting adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD001442.

van Loggerenberg F, Gray D, Gengiah S, Kunene P, Gengiah TN, Naidoo K, et al. A qualitative study of patient motivation to adhere to combination antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29(5):299–306.

Ochieng W, Kitawi RC, Nzomo TJ, Mwatelah RS, Kimulwo MJ, Ochieng DJ, et al. Implementation and operational research: correlates of adherence and treatment failure among Kenyan patients on long-term highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(2):49–56.

Sanne IM, Westreich D, Macphail AP, Rubel D, Majuba P, Van Rie A. Long term outcomes of antiretroviral therapy in a large HIV/AIDS care clinic in urban South Africa: a prospective cohort study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2009;12(30):38.

Bila B, Egrot M. Gender asymmetry in healthcare-facility attendance of people living with HIV/AIDS in Burkina Faso. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(6):854–61.

Hardon A, Davey S, Gerrits T, Hodgkin C, Irunde H, Kgatlwane J et al. From access to adherence: the challenges of antiretroviral treatment : studies from Botswana, Tanzania and Uganda 2006, World Health Organization, http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js13400e/. Accessed 29 Feb, 2018.

Boulle A, Van Cutsem G, Hilderbrand K, Cragg C, Abrahams M, Mathee S, et al. Seven-year experience of a primary care antiretroviral treatment programme in Khayelitsha, South Africa. AIDS. 2010;24(4):563–72.

El-Khatib Z, Katzenstein D, Marrone G, Laher F, Mohapi L, Petzold M, et al. Adherence to drug-refill is a useful early warning indicator of virologic and immunologic failure among HIV patients on first-line ART in South Africa. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17518.

Shamu T, Chimbetete C, Shawarira-Bote S, Mudzviti T, Luthy R. Outcomes of an HIV cohort after a decade of comprehensive care at Newlands Clinic in Harare, Zimbabwe: TENART cohort. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186726.

Staehelin C, Keiser O, Calmy A, Weber R, Elzi L, Cavassini M, et al. Longer term clinical and virological outcome of sub-Saharan African participants on antiretroviral treatment in the Swiss HIV cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(1):79–85.

Boender TS, Sigaloff KC, McMahon JH, Kiertiburanakul S, Jordan MR, Barcarolo J, et al. Long-term virological outcomes of first-line antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(9):1453–61.

Protopopescu C, Carrieri MP, Raffi F, Picard O, Harde L, Piroth L, et al. Brief report: prolonged viral suppression over a 12-year follow-up of HIV-infected patients: the persistent impact of adherence at 4 months after initiation of combined antiretroviral therapy in the ANRS CO8 APROCO-COPILOTE cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(3):293–7.

Carrieri MP, Raffi F, Lewden C, Sobel A, Michelet C, Cailleton V, et al. Impact of early versus late adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy on immuno-virological response: a 3-year follow-up study. Antivir Ther. 2003;8(6):585–94.

Meresse M, Carrieri MP, Laurent C, Kouanfack C, Protopopescu C, Blanche J, et al. Time patterns of adherence and long-term virological response to non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor regimens in the Stratall ANRS 12110/ESTHER trial in Cameroon. Antivir Ther. 2013;18(1):29–37.

Goldman JD, Cantrell RA, Mulenga LB, Tambatamba BC, Ried SE, Levy JW, et al. Simple adherence assessments to predict virologic failure among HIV-infected adults with discordant immunologic and clinical responses to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2008;24(8):1031–5.

Parruti G, Manzoli L, Toro PM, D'Amico G, Rotolo S, Graziani V, et al. Long-term adherence to first-line highly active antiretroviral therapy in a hospital-based cohort: predictors and impact on virologic response and relapse. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2006;20(1):48–56.

Mekuria LA, Prins JM, Yalew AW, Sprangers MA, Nieuwkerk PT. Which adherence measure - self-report, clinician recorded or pharmacy refill - is best able to predict detectable viral load in a public ART programme without routine plasma viral load monitoring? Tropical Med Int Health. 2016;21(7):856–69.

Bisson GP, Rowh A, Weinstein R, Gaolathe T, Frank I, Gross R. Antiretroviral failure despite high levels of adherence: discordant adherence–response relationship in Botswana. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(1):107–10.

Viswanathan S, Justice AC, Alexander GC, Brown TT, Gandhi NR, McNicholl IR, et al. Adherence and HIV RNA suppression in the current era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(4):493–8.

Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487–97.

Okatch H, Beiter K, Eby J, Chapman J, Marukutira T, Tshume O, et al. Brief report: apparent antiretroviral over-adherence by pill count is associated with HIV treatment failure in adolescents. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(5):542–5.

Pasternak AO, de Bruin M, Jurriaans S, Bakker M, Berkhout B, Prins JM, et al. Modest nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy promotes residual HIV-1 replication in the absence of virological rebound in plasma. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(9):1443–52.

Ingersoll KS, Cohen J. The impact of medication regimen factors on adherence to chronic treatment: a review of literature. J Behav Med. 2008;31(3):213–24.

Youle M. Overview of boosted protease inhibitors in treatment-experienced HIV-infected patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60(6):1195–205.

Chaiyachati KH, Ogbuoji O, Price M, Suthar AB, Negussie EK, Barnighausen T. Interventions to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a rapid systematic review. AIDS. 2014;28(Suppl 2):187–204.

Nachega JB, Knowlton AR, Deluca A, Schoeman JH, Watkinson L, Efron A, et al. Treatment supporter to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected south African adults. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(4):127–33.

World Health Organization, Global tuberculosis report 2017. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/. Accessed 08 Jun 2018.

Gebremariam MK, Bjune GA, Frich JC. Barriers and facilitators of adherence to TB treatment in patients on concomitant TB and HIV treatment: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:651.

Daftary A, Padayatchi N, O’Donnell M. Preferential adherence to antiretroviral therapy over tuberculosis treatment: a qualitative study of drug-resistant TB/HIV co-infected patients in South Africa. Glob Public Health. 2014;9(9):1107–16.

Webb Mazinyo E, Kim L, Masuku S, Lancaster JL, Odendaal R, Uys M, et al. Adherence to concurrent tuberculosis treatment and antiretroviral treatment among co-infected persons in South Africa, 2008–2010. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159317.

Gao X, Nau DP, Rosenbluth SA, Scott V, Woodward C. The relationship of disease severity, health beliefs and medication adherence among HIV patients. AIDS Care. 2000;12(4):387–98.

Hoffman R, Bardon A, Rosen S, Fox M, Kalua T, Xulu T, et al. Varying intervals of antiretroviral medication dispensing to improve outcomes for HIV patients (the INTERVAL study): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18:476.

Perriat D, Balzer L, Hayes R, Lockman S, Walsh F, Ayles H, et al. Comparative assessment of five trials of universal HIV testing and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(1).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the SAPiT and TRuTH study patients; the CAPRISA eThekwini clinical site treatment and pharmacy teams who worked on both studies, M. Govender for assistance with data clean-up for secondary analysis and R. Talakgale for statistical support.

Funding

The research infrastructure for conducting the SAPiT trial, including data management, laboratory and pharmacy cores were established through the Comprehensive International Program of Research on AIDS grant (CIPRA, grant # AI51794). The US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPfAR) funded the care of all the SAPiT patients, the Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria funded the cost for drugs used in the SAPiT trial. The TRUTH study was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Chevy Chase, MD, USA (grant # 55007065) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; Atlanta, GA, USA) Cooperative Agreement Number UY2G/ PS001350–02. Patient care was supported by the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health and the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR; Washington DC, USA). KN and TG were supported by the Columbia University-South Africa Fogarty AIDS International Training and Research Program (AITRP) funded by the Fogarty International Center, National Institutes of Health (grant # D43TW00231). No funding was received for this retrospective study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AM selected data for analysis; completed data review, data clean-up and wrote the manuscript. TG provided guidance in the writing and critical review of the manuscript. LL analyzed the data and reviewed the manuscript. KN was project director of the SAPiT trial, Principal Investigator of the TRuTH study and reviewed the manuscript. Approval for the final version of the manuscript was received from the 3 co-authors before submission to the journal. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The SAPiT and TRuTH studies were conducted under the oversight of the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (BREC) at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (BREC ref.: E107/05 [SAPiT]; BF051/09 [TRuTH]). Participants in the SAPiT and TRuTH studies provided written informed consent. The current study is a retrospective secondary analysis of previously collected anonymized data from the parent trials with no direct participant contact and received ethics approval (BREC ref.: BE046/16).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Moosa, A., Gengiah, T.N., Lewis, L. et al. Long-term adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a South African adult patient cohort: a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis 19, 775 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4410-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4410-8