Abstract

Background

Quinine (QN) remains an effective drug for malaria treatment. However, quinine resistance (QNR) in Plasmodium falciparum has been reported in many malaria-endemic regions particularly in African countries. Genetic polymorphism of the P. falciparum Na+/H+ exchanger (pfnhe1) is considered to influence QN susceptibility. Here, ms4760 alleles of pfnhe1 were analysed from imported African P. falciparum parasites isolated from returning travellers in Wuhan, Central China.

Methods

A total of 204 dried-blood spots were collected during 2011–2016. The polymorphisms of the pfnhe1 gene were determined using nested PCR with DNA sequencing.

Results

Sequences were generated for 99.51% (203/204) of the PCR products and 68.63% (140/204) of the isolates were analysed successfully for the pfnhe1 ms4760 haplotypes. In total, 28 distinct ms4760 alleles containing 0 to 5 DNNND and 1 to 3 NHNDNHNNDDD repeats were identified. For the alleles, ms4760–1 (22.86%, 32/140), ms4760–3 (17.86%, 25/140), and ms4760–7 (10.71%, 15/140) were the most prevalent profiles. Furthermore, 5 undescribed ms4760 alleles were reported.

Conclusions

The study offers an initial comprehensive analysis of pfnhe1 ms4760 polymorphisms from imported P. falciparum isolates in Wuhan. Pfnhe1 may constitute a good genetic marker to evaluate the prevalence of QNR in malaria-endemic and non-endemic regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Quinine (QN), a natural quinoline derivative from Cinchona bark, has been widely used in malaria-endemic regions for several centuries to treat severe malaria cases or malaria in the first trimester of pregnancy [1]. Following the guidelines of the World Health Organization (WHO), many malaria-endemic countries and regions have adopted artemisinin based combination therapies (ACTs) as first-line treatments since 2001 [2]. QN has been used as a second-line drug combined with doxycycline, tetracycline or clindamycin for uncomplicated malaria [3, 4]. In addition, with failures of previous therapies and limited availability of ACTs, QN is increasingly used as a first-line drug for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria in Uganda [5]. Although QN was an effective antimalaria drug, it has gradually decreased in sensitivity for malaria treatment [6,7,8,9,10]. In the early 1960s, the first QN clinical failure cases were reported in Brazil and Asia [11, 12]. Since then, more and more failure cases have been reported in Southeast Asia [6, 7], South America [6], and Africa [8,9,10].

To date, some genes associated with drug resistance have been identified, including Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter (pfcrt) [13], multidrug resistance 1 (pfmdr1) [14], multidrug resistance associated protein (pfmrp1) [15], dihydrofolate reductase (pfdhfr) [16], dihydropteroate synthase (pfdhps) [17], sodium/hydrogen exchanger (pfnhe1) [18], and kelch protein 13 (pfK13) [19]. However, the phenotype of quinine resistance (QNR) is complex and appears to be influenced by multiple genes located at different loci [20, 21]. Although the molecular mechanisms of QNR remain unclear, QN susceptibility in vitro is linked to polymorphisms in multiple genes, including pfmdr1 [14], pfcrt [22, 23], pfmrp [24] and pfnhe1 [20]. QNR-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been identified in pfmdr1 [14] at codons 86, 184, 1042, and 1246 and in pfcrt [23] at codon 76. Moreover, in our previous study, only 33.68% (65/193) of the isolates carried the N86Y184 wild-type allele in pfmdr1 and 49.43% (87/176) of the isolates carried the pfcrt K76 T mutation, suggesting moderate sensitivity to QN in Africa [25]. However, evidence for the involvement of pfnhe1 in QNR is still limited. A previous study demonstrated that pfnhe1 might be involved in QNR [26]. For the pfnhe1 gene, SNPs at codons 790, 894 and 950 and microsatellite variations in three different repeat sequences (msR1, ms3580 and ms4760) located on chromosome 13 of the P. falciparum genome have been identified [4]. However, these SNPs and microsatellite variations in msR1 and ms3580 showed no significant association with QN susceptibility [4]. Ms4760 with two or more DNNND repeats (Block II) was associated with a higher QN inhibition [20, 27]. Another study illustrated that the increased number of DNNND repeats (Block II) was related to a decreasing trend in QN susceptibility, and the increased number of NHNDNHNNDDD repeats (Block V) was related to increased QN susceptibility [28].

In light of these reports, we investigated the prevalence of pfnhe1 in patients who were infected with P. falciparum returning from different African countries and assessed whether pfnhe1 can be used as a molecular marker of QNR.

Methods

Clinical sample collection and genomic DNA extraction

In total, 204 dried-blood spots (DBSs) were collected from patients who were infected with P. falciparum returning from Africa and confirmed by the Wuhan Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC) during 2011–2016. These samples were examined using One Step Malaria HRP2/pLDH (P.f/Pan) tests (Wondfo, Guangzhou, China) and Giemsa-stained thick and thin peripheral blood smear examinations. The identities of Plasmodium spp. were confirmed by real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR. Genomic DNA (gDNA) of uncomplicated P. falciparum isolates was extracted from DBSs by using a TIANamp Blood DNA Kit (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To characterize the microsatellite repeats in pfnhe1, the ms4760 region (482 bp) of the pfnhe1 gene was amplified by nested PCR in 204 samples.

Nested PCR amplification of the pfnhe1 gene

DNA was amplified by nested PCR (Bio-Rad Mini MJ thermal cycler). The primary primers including NHE-A and NHE-B, and the secondary primers containing NHE-C and NHE-D were described in a previous study [29,30,31]. No negative control was set for the PCR. For the primary round of PCR, 0.5 μl of DNA was amplified with 10 μl 2× NovoStar Green PCR Mix (1.25 U/25 μl NovoStar Taq DNA Polymerase, 0.4 mM dNTP mixture, 2 × PCR buffer, and 4 mM Mg2+), 0.5 μl forward primer (10 μM), 0.5 μl reverse primer (10 μM), and sterile ultrapure water to a final volume of 20 μl. The gene target was amplified under the following conditions for the first run: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min; followed by 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min; and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. For the second round of PCR, 1.0 μl primary PCR products were amplified with a 50 μl reaction system, including 25 μl 2× NovoStar Green PCR Mix, 1.0 μl forward primer (10 μM), 1.0 μl reverse primer (10 μM), and 22 μl H2O. Secondary run conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min; followed by 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s; and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min.

Five microliters (5 μl) of nested PCR products were resolved by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels, and examined for quality under a UV light. Samples with bright bands were selected for DNA sequencing (Genewiz, Soochow, China). Sequences were then translated using the Edit Sequence tool and aligned using the MEGALIGN programme with DNAstar (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI, USA) software. The amino acid sequences were compared with the reference sequence from PlasmoDB (https://plasmodb.org/plasmo/) under Gene ID.: PF3D7_1303500.

Data analysis

All statistical data were analysed using SPSS 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism (version 5.01). Pfnhe1 ms4760 profiles were analysed, including the numbers of Block II and Block V. The prevalence of haplotypes between years and areas were compared using Pearson’s chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact test when applicable [32]. Specifically, Pearson’s chi-square tests were Yates corrected and Fisher’s exact tests were one-tailed. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

General information

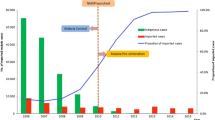

DNA blood samples from 204 patients with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria were collected and tested. All 204 samples were successfully amplified by nested PCR. Sequences were generated for 99.51% (203/204) of the PCR products and included 63 poor-quality sequencing products. Finally, 68.63% (140/204, 95% CI: 78.77 to 88.87%) of PCR products were analysed for pfnhe1 ms4760 haplotypes. In the 140 studied samples, the number of DNNND repeats (Block II) ranged from zero to five, with one, two and three repeats being more common and accounting for 27.86% (39/140), 42.14% (59/140) and 23.57% (33/140) of these samples, respectively (Fig. 1); combined repeats in Block II accounted for 93.57% (131/140) of the samples. The number of NHNDNHNNDDD repeats (Block V) ranged from one to three, with one repeat accounting for 33.57% (47/140) of the samples and two repeats accounting for 64.29% (90/140) of the samples; NHNDNHNNDDD represented the dominant repeat in these isolates (Fig. 1). Combined one and two repeats in Block V made up 97.86% (137/140) of the samples. The number of Block II and V repeats by different regions and years are presented in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

Genotyping of pfnhe1 ms4760 microsatellite polymorphisms

Among the 140 P. falciparum clinical isolates, 28 different alleles for pfnhe1 ms4760 were observed, including five profiles not previously described (Table 3). Multiple amino acid sequence alignments of these genotypes are displayed in Fig. 2. A total of 82.14% (23/28) of the alleles contained previously described ms4760 haplotypes. The three most prevalent profiles made up 51.43% (72/140) of the isolates, including 22.86% (32/140) ms4760–1, 17.86% (25/140) ms4760–3 and 10.71% (15/140) ms4760–7. The least common genetic polymorphisms were ms4760–52, ms4760–27, ms4760–30, ms4760–47, ms4760–48, and ms4760–79, each found in 0.71% (1/140) of the isolates. The 5 previously undescribed ms4760 haplotypes were named ms4760-WH1, ms4760-WH2, ms4760-WH3, ms4760-WH4 and ms4760-WH5 (Table 3). Of these five newly observed alleles, ms4760-WH1 was the most common, accounting for 2.86% (4/140), and the other four were all found at 0.71% (1/140).

Geographical distribution of ms4760 microsatellite polymorphisms

The distribution included twenty distinct ms4760 alleles from West Africa, 14 alleles from South Africa, 14 alleles from Central Africa, and 7 alleles from East Africa (Tables 3 and 4). As the most common allele, ms4760–1 was present in all regions of Africa but not in all countries (Table 3). Conversely, several alleles were only seen in partial regions or a specific country (Table 3 and 4). Only the three most numerous alleles (ms4760–1, ms4760–3, ms4760–7) were analysed using Pearson’s chi-square test. However, the three alleles were not significantly associated with four regions in Africa and excluded North Africa (P > 0.05). The ms4760 alleles in the parasite isolates from Nigeria, Congo, Angola, and Liberia accounted for 47.86% (67/140) of the samples. Furthermore, a combination of samples from Nigeria (50%, 14/28), Congo (32.14%, 9/28), Liberia (25%, 7/28), and Angola (21.43%, 6/28) was responsible for 67.86% (19/28) of the alleles. Although only 8 samples were included in the analysis for Mozambique, various ms4760 alleles (28.57%, 8/28) were detected. The same phenomenon can be observed for Guinea, Ghana, Zambia, Cameroon and Uganda (Table 4).

Annual distribution of ms4760 microsatellite polymorphisms

A total of 28 different ms4760 alleles were observed among the 140 imported African P. falciparum parasites isolated in Wuhan, China, between 2011 and 2016. These included two distinct ms4760 alleles in 2011, 13 alleles in 2012, 17 alleles in 2013, 12 alleles in 2014, 11 alleles in 2015, and 12 alleles in 2016 (Table 5). There was the highest number of alleles in 2013. Specifically, ms4760-WH1 was seen in 2013, 2014 and 2016. However, ms4760-WH2, WH3, WH4, and WH5 were only found in a single year. Of note, ms4760–1 was the most prevalent allele (23%; 32/140), and it was the only allele that was consistently observed throughout the 6-year study period, followed by ms4760–3 (18%; 25/140), and ms4760–7 (11%; 15/140; Table 5). These three most common alleles were further analyzed using Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. There was a statistically significant difference in the prevalence of ms4760–1 between 2011 and 2015 (P = 0.049). No significant associations were seen among years for the other alleles (P > 0.05). A significant association between ms4760–1 and ms4760–7 was also observed in 2015 (X2 = 6.020, P = 0.014). No significant associations were seen among the alleles for other years (P > 0.05).

Discussion

In the present study, the African distribution of ms4760 pfnhe1 polymorphisms from imported P. falciparum isolates in Wuhan during 2011–2016 was described. The number of DNNND repeats in Block II and NHNDNHNNDDD repeats in Block V ranged from 0 to 5 and 1 to 3, respectively. A total of 28 distinct ms4760 alleles were observed, including 23 referenced alleles [4, 33,34,35] and five that have not been previously characterized. A moderate level of pfnhe1 microsatellite sequence polymorphisms was found (28 genotypes for 140 isolates). Previous studies observed more or less ms4760 microsatellite profiles of pfnhe1, including 8 ms4760 alleles in 71 P. falciparum isolates from Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America [20], 15 alleles in 88 isolates from western Kenya [31], and 27 alleles in 74 isolates from Congo [36].

Although no valid molecular marker of QNR is currently available, several studies have studied the connection between pfnhe1 polymorphisms and QN susceptibility in vitro [20, 37,38,39,40]. Indeed, the QN sensitivities of isolates with different numbers of DNNND and NHNDHNNDDD repeats were compared [34]. Sequence polymorphisms of ms4760 in pfnhe1 have been analyzed, especially in Block II and V [41]. Studies of the association of polymorphisms in Block II and V with in vitro susceptibility to QN have shown conflicting results. A study showed that more than one DNNND repeat in Block II and one NHNDNHNNDDD repeat in Block V in ms4760 were associated with reduced QN sensitivity in vivo [41]. The same study illustrated that isolates from Vietnam and the China-Myanmar border containing two or more DNNND repeats showed a much lower susceptibility to QN than those containing 0 or 1 repeats, and an increased number of NHNDNHNNDDD repeats was associated with high QN susceptibility in vitro [33, 42]. Further, a study supported that the IC50 of QN for parasites with 3 DNNND repeats was significantly higher than those with 1 or 2 repeats [31]. Thus, in the present study of parasite isolates from South Africa, parasites should be considered to have decreased susceptibility to QN because of the increasing trend in the number of DNNND repeats and the decreasing trend in the number of NHNDNHNNDDD repeats.

Several studies have demonstrated the different relationship between QN susceptibility in vitro and pfnhe1 polymorphisms in isolates from western Kenya [31, 37]. These findings indicated that the presence of two DNNND repeats is linked to a decrease in QN susceptibility in vitro, and there was no association between the QN IC50 and NHNDNHNNDDD repeats [31, 37]. In one of the studies, parasites with one DNNND or NHNDNHNNDDD repeat were more susceptible to QN than those with more than one [37]. In addition, there was no association between QNR-associated Block II and Block V in pfnhe1 in Thailand isolates [43] and Indian isolates [44]. Thus, QN susceptibility has been connected with polymorphisms in the pfnhe1 ms4760 microsatellite in several studies [33, 42] but not in all.

These conflicting findings suggest that the role of pfnhe1 ms4670 microsatellites in QNR may be dependent on the genetic background of the P. falciparum parasites [18] and/or their geographic origin [36]. Ms4760–7 with three DNNND repeats is currently found with high frequency among Asian parasites [20, 28] and shows significantly reduced sensitivity to QN compared to ms4760–1 (with two DNNND repeats) [45]. According to the variation in the increasing trend of DNNND repeats and the decreasing trend of NHNDNHNNDDD repeats from 2011 to 2016 in the current study, it can be proposed that imported P. falciparum isolates from Africa have reduced susceptibility to QN. Thus, attention should be paid to this issue.

Among the 140 studied sequences, West Africa displayed the highest number of different alleles, followed by South Africa, Central Africa, East Africa, and North Africa. While several alleles were shared between different countries, others appeared restricted to specific regions. Our genotyping data are consistent with previous findings, showing three profiles (ms4760–1, ms4760–3 and ms4760–7) as the predominant alleles. The newly observed profiles were from West Africa (4 isolates), Central Africa (2 isolates), East Africa (1 isolate) and South Africa (1 isolate), which suggests great abundance in the genetic diversity of pfnhe1 in Africa. However, the sample sizes in this study were relatively small, particularly in 2011. Therefore, in vitro and in vivo studies with large-scale samples need to be considered for elucidating the role of pfnhe1 ms4760 as a molecular marker of QNR.

Conclusion

This primary study offers a comprehensive analysis of pfnhe1 ms4760 polymorphisms from imported P. falciparum isolates in Wuhan. It demonstrated that parasite isolates from Africa are moderately diverse. In addition, continuous surveillance for molecular markers of QNR is highly recommended.

Abbreviations

- ACTs:

-

Artemisinin based combination therapies

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Prevention and Control

- DBSs:

-

Dried-blood spots

- gDNA:

-

Genomic DNA.

- pfcrt :

-

Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter

- pfdhfr :

-

Plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase

- pfdhps :

-

Plasmodium falciparum dihydropteroate synthase

- pfK13 :

-

Plasmodium falciparum kelch protein 13

- pfmdr1 :

-

Plasmodium falciparum multidrug resistance 1

- pfmrp1 :

-

Plasmodium falciparum multidrug resistance associated protein

- pfnhe1 :

-

Plasmodium falciparum Na+/H+ exchanger

- QN:

-

Quinine

- QNR:

-

Quinine resistance

- SNPs:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Croft S. Antimalarial chemotherapy: mechanisms of action, resistance and new directions in drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2001;6(22):1151.

Davis TME, Karunajeewa HA, Ilett KF. Artemisinin-based combination therapies for uncomplicated malaria. Med J Aust. 2005;182(4):181–5.

Reyburn H: WHO Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria 2010, 340(may28 1):c2637.

Pascual A, Fall B, Wurtz N, Fall M, Camara C, Nakoulima A, Baret E, Diatta B, Fall KB, Mbaye PS, et al. In vitro susceptibility to quinine and microsatellite variations of the Plasmodium falciparum Na+/H+ exchanger transporter (Pfnhe-1) gene in 393 isolates from Dakar, Senegal. Malar J. 2013;12:189.

Achan J, Tibenderana JK, Kyabayinze D, Wabwire Mangen F, Kamya MR, Dorsey G, D'Alessandro U, Rosenthal PJ, Talisuna AO. Effectiveness of quinine versus artemether-lumefantrine for treating uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Ugandan children: randomised trial. BMJ. (Clinical research ed) 2009, 339:b2763.

Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, Sabchareon A, Attanath P. Treatment of quinine resistant falciparum malaria in Thai children. The Southeast Asian journal of tropical medicine and public health. 1983;14(3):357–62.

Pukrittayakamee S, Supanaranond W, Looareesuwan S, Vanijanonta S, White NJ. Quinine in severe falciparum malaria: evidence of declining efficacy in Thailand. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1994;88(3):324–7.

Kremsner PG, Winkler S, Brandts C, Neifer S, Bienzle U, Graninger W. Clindamycin in combination with chloroquine or quinine is an effective therapy for uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in children from Gabon. J Infect Dis. 1994;169(2):467–70.

Rogier C, Brau R, Tall A, Cisse B, Trape JF. Reducing the oral quinine-quinidine-cinchonin (Quinimax) treatment of uncomplicated malaria to three days does not increase the recurrence of attacks among children living in a highly endemic area of Senegal. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1996;90(2):175–8.

Kofoed PE, Mapaba E, Lopes F, Pussick F, Aaby P, Rombo L. Comparison of 3, 5 and 7 days' treatment with Quinimax for falciparum malaria in Guinea-Bissau. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91(4):462–4.

Giboda M, Denis MB. Response of Kampuchean strains of Plasmodium falciparum to antimalarials: in-vivo assessment of quinine and quinine plus tetracycline; multiple drug resistance in vitro. The Journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 1988;91(4):205–11.

Bjorkman A, Phillips-Howard PA. The epidemiology of drug-resistant malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990;84(2):177–80.

Fidock DA, Nomura T, Talley AK, Cooper RA, Dzekunov SM, Ferdig MT, Ursos LMB, bir Singh Sidhu A, Naudé B, Deitsch KW, et al. Mutations in the P. Falciparum digestive vacuole transmembrane protein PfCRT and evidence for their role in chloroquine resistance. Mol Cell. 2000;6(4):861–71.

Reed MB, Saliba KJ, Caruana SR, Kirk K, Cowman AF. Pgh1 modulates sensitivity and resistance to multiple antimalarials in Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2000;403(6772):906–9.

Raj DK, Mu J, Jiang H, Kabat J, Singh S, Sullivan M, Fay MP, McCutchan TF, Su XZ. Disruption of a Plasmodium falciparum multidrug resistance-associated protein (PfMRP) alters its fitness and transport of antimalarial drugs and glutathione. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(12):7687–96.

Cowman AF, Morry MJ, Biggs BA, Cross GA, Foote SJ. Amino acid changes linked to pyrimethamine resistance in the dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase gene of Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(23):9109–13.

Brooks DR, Wang P, Read M, Watkins WM, Sims PF, Hyde JE. Sequence variation of the hydroxymethyldihydropterin pyrophosphokinase: dihydropteroate synthase gene in lines of the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, with differing resistance to sulfadoxine. Eur J Biochem. 1994;224(2):397–405.

Nkrumah LJ, Riegelhaupt PM, Moura P, Johnson DJ, Patel J, Hayton K, Ferdig MT, Wellems TE, Akabas MH, Fidock DA. Probing the multifactorial basis of Plasmodium falciparum quinine resistance: evidence for a strain-specific contribution of the sodium-proton exchanger PfNHE. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2009;165(2):122–31.

Ariey F, Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Beghain J, Langlois A-C, Khim N, Kim S, Duru V, Bouchier C, Ma L, et al. A molecular marker of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2013;505:50.

Ferdig MT, Cooper RA, Mu J, Deng B, Joy DA, Su XZ, Wellems TE. Dissecting the loci of low-level quinine resistance in malaria parasites. Mol Microbiol. 2004;52(4):985–97.

Ekland EH, Fidock DA. Advances in understanding the genetic basis of antimalarial drug resistance. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007;10(4):363–70.

Cooper RA, Ferdig MT, Su XZ, Ursos LM, Mu J, Nomura T, Fujioka H, Fidock DA, Roepe PD, Wellems TE. Alternative mutations at position 76 of the vacuolar transmembrane protein PfCRT are associated with chloroquine resistance and unique stereospecific quinine and quinidine responses in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61(1):35–42.

Cooper RA, Lane KD, Deng B, Mu J, Patel JJ, Wellems TE, Su X, Ferdig MT. Mutations in transmembrane domains 1, 4 and 9 of the Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter alter susceptibility to chloroquine, quinine and quinidine. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63(1):270–82.

Mu J, Ferdig MT, Feng X, Joy DA, Duan J, Furuya T, Subramanian G, Aravind L, Cooper RA, Wootton JC, et al. Multiple transporters associated with malaria parasite responses to chloroquine and quinine. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49(4):977–89.

Yao Y, Wu K, Xu M, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Yang W, Shang R, Du W, Tan H, Chen J, et al. Surveillance of genetic variations associated with antimalarial resistance of Plasmodium falciparum isolates from returned migrant Workers in Wuhan, Central China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(9).

Bennett TN, Patel J, Ferdig MT, Roepe PD. Plasmodium falciparum Na+/H+ exchanger activity and quinine resistance. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2007;153(1):48–58.

Gadalla NB, Tavera G, Mu J, Kabyemela ER, Fried M, Duffy PE, Sa JM, Wellems TE. Prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum anti-malarial resistance-associated polymorphisms in pfcrt, pfmdr1 and pfnhe1 in Muheza, Tanzania, prior to introduction of artemisinin combination therapy. Malar J. 2015;14:129.

Henry M, Briolant S, Zettor A, Pelleau S, Baragatti M, Baret E, Mosnier J, Amalvict R, Fusai T, Rogier C. Plasmodium falciparum Na+/H+ exchanger 1 transporter is involved in reduced susceptibility to quinine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(5):1926–30.

Vinayak S, Mittra P, Sharma YD. Wide variation in microsatellite sequences within each Pfcrt mutant haplotype. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2006;147(1):101–8.

Vinayak S, Alam MT, Upadhyay M, Das MK, Dev V, Singh N, Dash AP, Sharma YD. Extensive genetic diversity in the Plasmodium falciparum Na+/H+ exchanger 1 transporter protein implicated in quinine resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51(12):4508–11.

Cheruiyot J, Ingasia LA, Omondi AA, Juma DW, Opot BH, Ndegwa JM, Mativo J, Cheruiyot AC, Yeda R, Okudo C, et al. Polymorphisms in Pfmdr1, Pfcrt, and Pfnhe1 genes are associated with reduced in vitro activities of quinine in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from western Kenya. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(7):3737–43.

Baraka V, Ishengoma DS, Fransis F, Minja DT, Madebe RA, Ngatunga D, Van Geertruyden JP. High-level Plasmodium falciparum sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine resistance with the concomitant occurrence of septuple haplotype in Tanzania. Malar J. 2015;14:439.

Meng H, Zhang R, Yang H, Fan Q, Su X, Miao J, Cui L, Yang Z. In vitro sensitivity of Plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates from the China-Myanmar border area to quinine and association with polymorphism in the Na+/H+ exchanger. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(10):4306–13.

Baliraine FN, Nsobya SL, Achan J, Tibenderana JK, Talisuna AO, Greenhouse B, Rosenthal PJ. Limited ability of Plasmodium falciparum pfcrt, pfmdr1, and pfnhe1 polymorphisms to predict quinine in vitro sensitivity or clinical effectiveness in Uganda. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(2):615–22.

Menard D, Andriantsoanirina V, Khim N, Ratsimbasoa A, Witkowski B, Benedet C, Canier L, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Durand R. Global analysis of Plasmodium falciparum Na(+)/H(+) exchanger (pfnhe-1) allele polymorphism and its usefulness as a marker of in vitro resistance to quinine. International journal for parasitology Drugs and drug resistance. 2013;3:8–19.

Briolant S, Pelleau S, Bogreau H, Hovette P, Zettor A, Castello J, Baret E, Amalvict R, Rogier C, Pradines B. In vitro susceptibility to quinine and microsatellite variations of the Plasmodium falciparum Na+/H+ exchanger (Pfnhe-1) gene: the absence of association in clinical isolates from the republic of Congo. Malar J. 2011;10:37.

Okombo J, Kiara SM, Rono J, Mwai L, Pole L, Ohuma E, Borrmann S, Ochola LI, Nzila A. In vitro activities of quinine and other antimalarials and pfnhe polymorphisms in Plasmodium isolates from Kenya. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(8):3302–7.

Andriantsoanirina V, Ménard D, Rabearimanana S, Hubert V, Bouchier C, Tichit M, Bras JL, Durand R. Association of microsatellite variations of Plasmodium falciparum Na+/H+ exchanger (Pfnhe-1) gene with reduced in vitro susceptibility to quinine: lack of confirmation in clinical isolates from Africa. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2010;82(5):782–7.

Pelleau S, Bertaux L, Briolant S, Ferdig MT, Sinou V, Pradines B, Parzy D, Jambou R. Differential association of Plasmodium falciparum Na+/H+ exchanger polymorphism and quinine responses in field- and culture-adapted isolates of Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(12):5834–41.

Kone A, Mu J, Maiga H, Beavogui AH, Yattara O, Sagara I, Tekete MM, Traore OB, Dara A, Dama S, et al. Quinine treatment selects the pfnhe-1 ms4760-1 polymorphism in Malian patients with falciparum malaria. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(3):520–7.

Jovel IT, Bjorkman A, Roper C, Martensson A, Ursing J. Unexpected selections of Plasmodium falciparum polymorphisms in previously treatment-naive areas after monthly presumptive administration of three different anti-malarial drugs in Liberia 1976-78. Malar J. 2017;16(1):113.

Sinou V, Quang le H, Pelleau S, Huong VN, Huong NT, Tai le M, Bertaux L, Desbordes M, Latour C, Long LQ, et al. Polymorphism of Plasmodium falciparum Na(+)/H(+) exchanger is indicative of a low in vitro quinine susceptibility in isolates from Viet Nam. Malar J. 2011;10:164.

Poyomtip T, Suwandittakul N, Sitthichot N, Khositnithikul R, Tanariya P, Mungthin M. Polymorphisms of the pfmdr1 but not the pfnhe-1 gene is associated with in vitro quinine sensitivity in Thai isolates of Plasmodium falciparum. Malar J. 2012;11(1):7.

Choudhary V, Sharma YD. Extensive heterozygosity in flanking microsatellites of Plasmodium falciparum Na+/H+ exchanger (pfnhe-1) gene among Indian isolates. Acta Trop. 2009;109(3):241–4.

Bai Y, Zhang J, Geng J, Xu S, Deng S, Zeng W, Wang Z, Ngassa Mbenda HG, Zhang J, Li N, et al. Longitudinal surveillance of drug resistance in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from the China-Myanmar border reveals persistent circulation of multidrug resistant parasites. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist. 2018;8(2):320–8.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Department of Schistosomiasis and Endemic Diseases, Wuhan Center for Disease Prevention and Control, and to all participants who contributed their blood samples.

Funding

This study was supported by the Foundation for Innovative Research Team of Hubei University of Medicine (Grant Number FDFR201603), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 81802046), the Education Agency Major Project of Hubei Province of China (Grant Number D20162101) and Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for College Students (Grant Number 201710929040), the cost of experiments comes from these funding. The funder only provided economic support and had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JL and YY conceived and designed the experiments. KW, FC and MMX coordinated the field collections of patient isolates. YY, ZYL, GQL, and TTJ performed the experiments. JL, YY, WXD, FL, RGL and HBT analyzed the data. JL, YY and TTJ wrote the paper. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Current study was approved by the ethics committees of Hubei University of Medicine and Wuhan City Center for Disease Prevention and Control. The written informed consent was obtained from all participated individuals.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, K., Yao, Y., Chen, F. et al. Analysis of Plasmodium falciparum Na+/H+ exchanger (pfnhe1) polymorphisms among imported African malaria parasites isolated in Wuhan, Central China. BMC Infect Dis 19, 354 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3921-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3921-7