Abstract

Background

Lactococcus garvieae is an unusual cause of infective endocarditis (IE). No current diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines are available to treat IE caused by these organisms. Based on a case report, we provide a review of the literature of IE caused by L. garvieae and highlight diagnostic and treatment challenges of these infections and implications for management.

Case presentation

A 50-year-old Asian male with mitral prosthetic valve presented to the hospital with intracranial haemorrhage, which was successfully treated. Three weeks later, he complained of generalized malaise. Further work up revealed blood cultures positive for Gram-positive cocci identified as L. garvieae by MALDI-TOF. An echocardiogram confirmed the diagnosis of IE. Susceptibility testing showed resistance only to clindamycin. Vancomycin plus gentamicin were started as empirical therapy and, subsequently, the combination of ceftriaxone plus gentamicin was used after susceptibility studies were available. After two weeks of combination therapy, ceftriaxone was continued as monotherapy for six additional weeks with good outcome.

Conclusions

Twenty-five cases of IE by Lactococcus garvieae have been reported in the literature. Compared to other Gram-positive cocci, L. garvieae affects more frequently patients with prosthetic valves. IE presents in a subacute manner and the case fatality rate can be as high as 16%, comparable to that of streptococcal IE (15.7%). Reliable methods for identification of L. garvieae include MALDI-TOF, 16S RNA PCR, API 32 strep kit and BD Automated Phoenix System. Recommended antimicrobials for L. garvieae IE are ampicillin, amoxicillin, ceftriaxone or vancomycin in monotherapy or in combination with gentamicin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lactococcus garvieae are Gram-positive cocci previously considered part of the genus Streptococcus. In 1985, these organisms were classified within the genus lactococci due to DNA-DNA hybridization studies and fatty acid profiles [1,2,3]. Currently, the genus Lactococcus contains 11 species [4]. L. garvieae is associated with fish infections in warm water causing outbreaks of haemorrhagic sepsis in rainbow trout [2, 5]. These organisms have also been isolated from raw cow milk, goat cheese, fish, beef meat, poultry and pork meat [6]. Human infections caused by L. garvieae have been reported in different countries and have been associated to ingestion of raw seafood. Indeed, a study by Wang et al. found that among four patients with invasive L. garvieae infection, three had ingested sea food contaminated by these organisms [7]. Infective endocarditis (IE) is a known disease caused by L. garvieae, however, the true incidence of disease is difficult to assess since misidentification with other Gram-positive cocci like Enterococcus spp. and streptococci (employing different automatized diagnostic tools) has commonly been reported [8, 9]. Here, we report a case of L. garvieae IE and describe the risk factors associated with this disease, the diagnostic challenges to identify these organisms and therapeutic approaches used to treat these infections. We seek to provide clinicians with relevant and updated information on the diagnosis and management of IE caused by the genus L. garvieae.

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE and LILACS using the following MeSH, major and free terms: “endocarditis”, “endocarditis, bacterial”, “endocarditis, subacute bacterial”, “endocarditis bacteriana”, “endocarditis bacteriana subaguda” and “lactococo”, “lactococcus”, “lactococcus lactis”, “lactococcus garvieae”, “lactococcus garvieae endocarditis”. We selected all the articles in Spanish, English and French published before March 2018 that included case reports of endocarditis and Lactococcus in the titles.

Case presentation

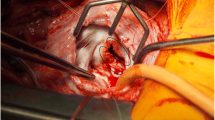

A 50-year-old Asian man with history of rheumatic heart disease (without hypertension) and mechanical prosthetic mitral valve replacement 5 years before admission, dyslipidaemia and reflux esophagitis presented to the emergency room with severe bilateral occipital headache. He was diagnosed with an intracranial haemorrhage confirmed by CT brain. At the time of admission, his INR was within therapeutic range (2.35). After initial work up, the patient was hospitalized for 10 days and discharged without any residual neurologic sequelae. Atorvastatin was prescribed. No fever or elevation of the C reactive protein (CRP) or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) were identified during the admission. He worked as an accountant and had been living in the US for the past 30 years with no recent travel outside the US. Three weeks later, he complained of flu-like symptoms and oseltamivir was prescribed. A week later, the patient returned to the hospital with epistaxis, haematuria, and malaise without fever. Physical examination was unremarkable with normal neurologic exam, except for a pansystolic heart murmur. Blood tests showed elevated white blood count (14.5 × 109/L) and serum creatinine of 1.54 mg/dl (Normal value: 0.8–1.2 mg/dl). CRP and ESR were also elevated (34.5 mg/dl and 75 mm/h, respectively). A Chest X ray was found without acute abnormalities and the urine analysis showed no abnormalities. Three days after admission, blood cultures were positive for Gram-positive cocci in chains in 4 out of 4 bottles. Transthoracic echocardiography was inconclusive, but a transoesophageal echocardiography (TEE) revealed a 0.8 cm vegetation on the ventricular side of the native aortic valve without valve dysfunction, confirming the diagnosis of IE. Empirical intravenous antibiotic therapy was started with vancomycin 30 mg/kg/day in divided doses and gentamicin 3 mg/kg/day. The organism was recovered on blood agar and was identified by MALDI-TOF as Lactococcus garvieae. Susceptibility testing showed resistance to clindamycin, whereas it was susceptible to penicillin (MIC 0.25 μg/ml), ceftriaxone (MIC 0.25 μg/ml), vancomycin (MIC 1.5 μg/ml) and levofloxacin (MIC 2 μg/ml). With these results, vancomycin was switched to ceftriaxone 2 g IV twice daily plus gentamicin as combination therapy for the first 2 weeks. This regimen was chosen based on previous cases since no specific guidelines exist on how to treat these organisms. Gentamicin was stopped after two weeks and ceftriaxone was continued for 4 additional weeks pending a surgical decision. In the setting of intracranial bleed and IE, rupture of a mycotic aneurysm was highly suspected and the patient was considered a possible surgical candidate for aortic valve replacement. CT angiography of the brain (5 weeks after the initial episode of intracranial bleed) showed encephalomalacia in the left parietal and occipital lobes with subacute to chronic haemorrhage, with no mycotic aneurysms. After several discussions, the stroke team agreed on resuming anticoagulation with heparin IV drip (considering that the patient had a “chronic” bleed without active haemorrhage and that the risk of embolism was high due to the presence of a mechanical heart valve and IE). It was also suggested postponing aortic valve replacement for at least 4 weeks after effective antimicrobial therapy. After 4 weeks of therapy, decrease of inflammatory markers (CRP to 8.5 mg/dl and ESR to 40 mm/h) was observed and repeat blood cultures were negative.

Upon further questioning, the patient admitted that his diet was rich in grilled fish. Additionally, he reported a long history of chronic epigastric pain for 5 years, for which he had been taking over the counter medicines. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed severe gastritis and reflux esophagitis. After 6 weeks of treatment for IE, the patient had clinical improvement with no recurrence of infection but repeat TEE revealed severe aortic valve insufficiency. He underwent mechanical aortic valve replacement without complications and cultures from the excised valve were sterile.

Discussion and conclusion

Different clinical presentations of subacute IE make it challenging to make an early diagnosis of infection and can cause delays in appropriate treatment. In our case, treatment of IE was delayed due to low suspicion of the disease at presentation and the occurrence of the intracranial haemorrhage. Importantly, collection of blood cultures as soon as infection was suspected, led to isolation of L. garvieae and identification using MALDI-TOF.

A total of 25 cases of IE caused by L. garvieae were identified in the literature review [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Among the 25 cases of IE caused by L. garvieae (Table 1), 58% were reported in men and the median age of presentation was 68 years. Median duration of symptoms before consulting was 14 days (IQR = 6.2–21). The most common reported symptoms were fever (68%) and chills (28%). Presence of heart murmurs was the most common finding in the physical examination (72%). Laboratory tests usually showed leucocytosis, elevated CRP and ESR. Echocardiogram was reported in 24 out of 25 cases and vegetations were identified in 83.3%. The mitral valve was the most frequently involved valve. Colonoscopy was performed in 5 cases, all of which reported colonic polyps. The median duration of antimicrobial therapy was 42 days (IQR 41–45.5).

When compared to other Gram-positive microorganisms, L. garvieae seems to affect more frequently patients with prosthetic valves. In our review, 52% (n = 13) patients with L garvieae IE had prosthetic valves, while large cohorts of endocarditis caused by Enterococcus spp., Streptococcus spp., Coagulase negative Staphylococci (CoNS) and S. aureus, report prosthetic valve involvement in 15.3–35%, 16.3–17.2%, 28–32.2% and 15.3–16% of cases, respectively [31,32,33]. Complications of IE such as valve dehiscence or rupture, septic emboli, renal failure, shock, stroke and heart failure were reported in 50% (n = 12) of cases. Surgery for valve repair or replacement was performed in 48% of cases. The case fatality rate of L. garvieae IE was 16% (n: 4), which is low compared to that of other GPC such as S. aureus (44.4%), Enterococcus spp. (23%) and CoNS (33.4%), but comparable to that of streptococci IE (15.7%) [32].

The ingestion of raw sea food or exposure to fish, the presence of colonic polyps and the repeated exposure to dairy products have been postulated to be risk factors for infection by L. garvieae [7]. Less than half of patients with IE caused by L. garvieae reported ingestion of fish (including raw or cooked) [7, 15, 19, 23, 24, 26,27,28, 30] or were diagnosed with a concomitant GI disorder [10, 13, 19,20,21, 24, 28,29,30]. Our patient reported both conditions. The most important predisposing factor in these patients appears to be the presence of previous valvular disease. Of note, colonoscopy may be considered in patients with L. garvieae IE to rule out colonic polyps.

For species identification, MALDI-TOF, 16S RNA PCR, API 32 strep kit (BioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France), Vitek 2 kit with GP identification card (BioMérieux) and BD Automated Phoenix System seem to be reliable techniques for the identification of L. garvieae in our series. However, the Vitek 2 reported misidentification of Enterococcus spp. as L. garvieae in one case [8]. In contrast, the API 20 Strep (BioMérieux, Marcy-l’Etoile, France) and Microscan walk away system (Dade Behring, inc., Sacramento, CA) often misidentified the genus L. garvieae [8, 9]. Since the therapeutic approach for enterococci may be different to that used for Lactococcus, confirmation of identification should be performed with a reliable method. As no breakpoints for antibiotic susceptibility have been determined for Lactococcus spp. by the CLSI or EUCAST, most authors used those for viridans-group streptococci (VGS), group B streptococci, Enterococcus spp. or Staphylococcus spp. With these breakpoints, most L. garvieae isolates show intermediate resistance to penicillin and resistance to clindamycin [8, 9, 13, 22].

In summary, IE caused by L. garvieae may be a life-threatening infection. The most important predisposing factor is previous valvular disease. An association with gastrointestinal disease and consumption of fish has been established. Reliable methods for identification of L. garvieae include MALDI-TOF, 16S RNA PCR, API 32 strep kit (BioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) and BD Automated Phoenix System. Based on prior case reports and our own patient case, the recommended antimicrobials for L. garvieae are ampicillin (2 g every 4 h), amoxicillin (200 mg/kg/day divided in 4–6 doses), ceftriaxone (2 g every 12–24 h) or vancomycin (30 mg/kg/day divided in 2–3 doses) as monotherapy or in combination with gentamicin (3 mg/kg/day). Doses were defined using the recommendations for the treatment of VGS and enterococcal IE published by the American Heart Association/Infectious Diseases Society of America (AHA-IDSA) and European Society of Cardiology guidelines [34, 35]. It is unclear if combination therapy is needed (in cases where aminoglycoside toxicity is an issue), given that 5 out of 25 patients with L. garvieae IE were treated with vancomycin [9, 15, 17], teicoplanin [17] or ampicillin [8] monotherapy with good outcomes. Further, the majority of patients in the L. garvieae group who died were treated at some point with monotherapy and combination therapy.

Abbreviations

- AF:

-

Atrial fibrillation

- AKI:

-

Acute kidney injury,

- AMC:

-

Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid

- AMK:

-

Amikacin

- AMP:

-

Ampicillin

- AMX:

-

Amoxicillin

- BD:

-

Becton Dickinson

- CABG:

-

Coronary artery bypass graft

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- CDN:

-

Cefditoren

- CEF:

-

Cephalothin

- CFZ:

-

Cefazolin

- CHF:

-

Cardiac heart failure

- CHL:

-

Chloramphenicol

- CIP:

-

Ciprofloxacin

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- CLI:

-

Clindamycin

- CLL:

-

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia

- CLR:

-

Clarithromycin

- CLSI:

-

Clinical and laboratory standards institute

- CLSI:

-

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- CONS:

-

Coagulase negative staphylococci

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CRO:

-

Ceftriaxone

- CRP:

-

C Reactive Protein

- CT:

-

Computed Tomography

- CTX:

-

Cefotaxime

- DAP:

-

Daptomycin

- DM2:

-

Diabetes mellitus type 2

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- ERY:

-

Erythromycin

- ESR:

-

Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate

- EUCAST:

-

European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

- GEN:

-

Gentamicin

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal

- GP:

-

Gram positive

- GPC:

-

Gram positive cocci

- I:

-

Intermediate

- IE:

-

Infective Endocarditis

- INR:

-

International Normalized Ratio

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- IV:

-

Intravenous

- LG:

-

Lactococcus garvieae

- LVX:

-

Levofloxacin

- LZD:

-

Linezolid

- MALDI-TOF:

-

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time of Flight

- MEM:

-

Meropenem

- MIC:

-

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

- MXF:

-

Moxifloxacin

- NHL:

-

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

- NI:

-

No information

- OFX:

-

Ofloxacin

- PCR:

-

Polymerase Chain Reaction

- PEN:

-

Penicillin

- R:

-

Resistant

- RIF:

-

Rifampin

- RNA:

-

Ribonucleic acid

- S:

-

Sensitive

- STR:

-

Streptomycin

- SXT:

-

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole

- TEC:

-

Teicoplanin

- TEE:

-

Transoesophageal Echocardiography

- TET:

-

Tetracyclin

- TOB:

-

Tobramycin

- TZP:

-

Piperacillin-tazobactam

- VAN:

-

Vancomycin

References

Schleifer KH, Kraus J, Dvorak C, Kilpper-Bälz R, Collins MD, Fischer W. Transfer of Streptococcus lactis and related streptococci to the genus Lactococcus gen. Nov. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1985;6(2):183–95.

Vendrell D, Balcázar JL, Ruiz-Zarzuela I, de Blas I, Gironés O, Múzquiz JL. Lactococcus garvieae in fish: a review. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006 Jul;29(4):177–98.

Collins MD, Farrow JA, Phillips BA, Kandler O. Streptococcus garvieae sp. nov. and Streptococcus plantarum sp. nov. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129(11):3427–31.

Varsha KK, Nampoothiri KM. Lactococcus garvieae subsp. bovis subsp. nov., lactic acid bacteria isolated from wild gaur (Bos gaurus) dung, and description of Lactococcus garvieae subsp. garvieae subsp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016;66(10):3805–9.

Cavanagh D, Fitzgerald GF, McAuliffe O. From field to fermentation: the origins of Lactococcus lactis and its domestication to the dairy environment. Food Microbiol. 2015;47:45–61.

Gibello A, Galán-Sánchez F, Blanco MM, Rodríguez-Iglesias M, Domínguez L, Fernández-Garayzábal JF. The zoonotic potential of Lactococcus garvieae: an overview on microbiology, epidemiology, virulence factors and relationship with its presence in foods. Res Vet Sci. 2016;109:59–70.

Wang C-YC, Shie H-S, Chen S-C, Huang J-P, Hsieh I-C, Wen M-S, et al. Lactococcus garvieae infections in humans: possible association with aquaculture outbreaks: Lactococcus Garvieae infections in humans. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;61(1):68–73.

Vinh DC, Nichol KA, Rand F, Embil JM. Native-valve bacterial endocarditis caused by Lactococcus garvieae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;56(1):91–4.

Navas ME, Hall G, El Bejjani D. A case of endocarditis caused by Lactococcus garvieae and suggested methods for identification. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(6):1990–2.

Clavero R, Escobar J, Ramos-Avasola S, Merello L, Álvarez F. Lactococcus garvieae endocarditis in a patient undergoing chronic hemodialysis. First case report in Chile and review of the literature. Rev Chil Infectol. 2017;34(4):397–403.

Fefer JJ, Ratzan KR, Sharp SE, Saiz E. Lactococcus garvieae endocarditis: report of a case and review of the literature. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;32(2):127–30.

Fihman V, Raskine L, Barrou Z, Kiffel C, Riahi J, Berçot B, et al. Lactococcus garvieae endocarditis: identification by 16S rRNA and sodA sequence analysis. J Inf Secur. 2006;52(1):e3–6.

Fleming H, Fowler SV, Nguyen L, Hofinger DM. Lactococcus garvieae multi-valve infective endocarditis in a traveler returning from South Korea. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2012;10(2):101–4.

Heras Cañas V, Pérez Ramirez MD, Bermudez Jiménez F, Rojo Martin MD, Miranda Casas C, Marin Arriaza M, et al. Lactococcus garvieae endocarditis in a native valve identified by MALDI-TOF MS and PCR-based 16s rRNA in Spain: a case report. New Microbes New Infect. 2015;5:13–5.

Hirakawa TF, da Costa FAA, Vilela MC, Rigon M, Abensur H. Araújo MRE de. Lactococcus garvieae endocarditis: first case report in Latin America. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2011;97(5):e108–10.

Igneri L, Eltoukhy N, Shaffer A, Goren R. 1200: a rare case of lactococcus garvieae endocarditis in a critically ill patient. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:302.

James PR, Hardman SM, Patterson DL. Osteomyelitis and possible endocarditis secondary to Lactococcus garvieae: a first case report. Postgrad Med J. 2000;76(895):301–3.

Li W-K, Chen Y-S, Wann S-R, Liu Y-C, Tsai H-C. Lactococcus garvieae endocarditis with initial presentation of acute cerebral infarction in a healthy immunocompetent man. Intern Med Tokyo Jpn. 2008;47(12):1143–6.

Lim FH, Jenkins DR. Native valve endocarditis caused byLactococcus garvieae: an emerging human pathogen. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;22(2017):1–3.

Ortiz C, López J, Del Amo E, Sevilla T, García PE, San Román JA. Lactococcus garvieae infective endocarditis: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Rev Espanola Cardiol Engl Ed. 2014;67(9):776–8.

Rasmussen M, Björk Werner J, Dolk M, Christensson B. Lactococcus garvieae endocarditis presenting with subdural haematoma. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014;1(14):13.

Russo G, Iannetta M, D’Abramo A, Mascellino MT, Pantosti A, Erario L, et al. Lactococcus garvieae endocarditis in a patient with colonic diverticulosis: first case report in Italy and review of the literature. New Microbiol. 2012;35(4):495–501.

Suh Y, Ja Kim M, Seung Jung J, Pil Chong Y, Hwan Kim C, Kang Y, et al. Afebrile multi-valve infective endocarditis caused by Lactococcus garvieae: a case report and literature review. Intern Med Tokyo Jpn. 2016;55(8):1011–5.

Tsur A, Slutzki T, Flusser D. Lactococcus garvieae endocarditis on a prosthetic biological aortic valve. Zoonoses Public Health. 2015;62(6):435–7.

Watanabe Y, Naito T, Kikuchi K, Amari Y, Uehara Y, Isonuma H, et al. Infective endocarditis with Lactococcus garvieae in Japan: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:356.

Wilbring M, Alexiou K, Reichenspurner H, Matschke K, Tugtekin SM. Lactococcus garvieae causing zoonotic prosthetic valve endocarditis. Clin Res Cardiol Off J Ger Card Soc. 2011;100(6):545–6.

Yiu K-H, Siu C-W, TO KK-W, Jim M-H, Lee KL-F, Lau C-P, et al. A rare cause of infective endocarditis; Lactococcus garvieae. Int J Cardiol. 2007;114(2):286–7.

Zuily S, Mami Z, Meune C. Lactococcus garvieae endocarditis. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;104(2):138–9.

Bazemore TC, Maskarinec SA, Zietlow K, Hendershot EF, Perfect JR. Familial adenomatous polyposis manifesting asLactococcusEndocarditis: a case report and review of the association ofLactococcuswith underlying gastrointestinal disease. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2016;2016:5805326.

Landeloos E, Van Camp G, De Beenhouwer H. Lactococcus garviae prosthetic mitral valve endocarditis: a case report and literature review. Clin Microbiol Newsl. 2017;39(16):130–1.

Murdoch DR, Corey GR, Hoen B, Miró JM, Fowler VG, Bayer AS, et al. Clinical presentation, etiology, and outcome of infective endocarditis in the 21st century: the international collaboration on endocarditis-prospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(5):463–73.

Muñoz P, Kestler M, De Alarcon A, Miro JM, Bermejo J, Rodríguez-Abella H, et al. Current epidemiology and outcome of infective endocarditis: a multicenter, prospective, cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(43):e1816.

Chirouze C, Athan E, Alla F, Chu VH, Ralph Corey G, Selton-Suty C, et al. Enterococcal endocarditis in the beginning of the 21st century: analysis from the international collaboration on endocarditis-prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19(12):1140–7.

Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, Fowler VG, Tleyjeh IM, Rybak MJ, et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and Management of Complications: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132(15):1435–86.

Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, Bongiorni MG, Casalta J-P, Del Zotti F, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: the task force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J. 2015;36(44):3075–128.

Funding

This work supported by NIH-National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant number K24-AI114818 to CAA. This grant serves for undertaking research performed in CAA lab and for publication.

The funders of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

No data or materials are available.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AM, AD and CAA wrote the manuscript and structured the literature review. CAA, AM, SG and CN took care of the patient and collected clinical data. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Does not apply.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was given by the patient to publish the information in this case report.

Competing interests

CAA has received grant support from Merck, Entasis and MeMed diagnostics. The other authors have no competing interests to declare.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Malek, A., De la Hoz, A., Gomez-Villegas, S.I. et al. Lactococcus garvieae, an unusual pathogen in infective endocarditis: case report and review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis 19, 301 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3912-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3912-8