Abstract

Background

Non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) cause the majority of bloodstream infections in Ghana, however the mode of transmission and source of invasive NTS in Africa are poorly understood. This study compares NTS from water sources and invasive bloodstream infections in rural Ghana.

Methods

Blood from hospitalised, febrile children and samples from drinking water sources were analysed for Salmonella spp. Strains were serotyped to trace possible epidemiological links between human and water-derived isolates.. Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed,

Results

In 2720 blood culture samples, 165 (6%) NTS were isolated. S. Typhimurium (70%) was the most common serovar followed by S. Enteritidis (8%) and S. Dublin (8%). Multidrug resistance (MDR) was found in 95 (58%) NTS isolates, including five S. Enteritidis. One S. Typhimurium showed reduced fluroquinolone susceptibility. In 511 water samples, 19 (4%) tested positive for S. enterica with two isolates being resistant to ampicillin and one isolate being resistant to cotrimoxazole. Serovars from water samples were not encountered in any of the clinical specimens.

Conclusion

Water analyses demonstrated that common drinking water sources were contaminated with S. enterica posing a potential risk for transmission. However, a link between S. enterica from water sources and patients could not be established, questioning the ability of water-derived serovars to cause invasive bloodstream infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

S. enterica causes more than 1.2 million annual deaths worldwide, the majority occurring in resource-poor countries [1]. Salmonella infections other than typhoid fever, so-called non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS), are usually limited to gastrointestinal disease in industrialized countries. In contrast, in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), NTS are one of the most frequent causes of bacterial bloodstream infections in both adults and children, associated with high case fatality rates of 20 to 47%, also in Ghana [2,3,4,5]. In industrialized countries, infections with NTS are typically of zoonotic origin with regular food-borne outbreaks being described [6,7,8]. A broad spectrum of animal products such as poultry, beef, pork and eggs as well as contact to farm animals have been associated with infections [9,10,11]. The Salmonella serovar Enteritidis has been strongly linked to poultry farming and egg production [12].

So far, studies from SSA on S. enterica isolated from livestock and animal products demonstrate a broad Salmonella serovar distribution of types not commonly associated with human infections hence suggesting other transmission routes [13,14,15]. Despite the disease burden caused, the exact mode of transmission of invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella (iNTS) is largely unknown.

Residents in many SSA regions often do not have access to safe drinking water, but use water from sources such as rivers, lakes, wells and boreholes, which may be contaminated with bacteria from environmental sources, such as sewage wastewater in the absence of good sanitary facilities.

There is evidence that Salmonella serovars are specifically adapted to the human host with no or limited potential to be transmitted beyond this reservoir, suggesting anthroponotic transmission as a major route of recently evolved African strains [16,17,18]. So far, comparisons on serovar level of human and environmental Salmonella isolates from SSA have rarely been conducted. This information is important to understand reservoirs, and potential transmission routes of iNTS in order to institute efficient management and control strategies.

In the rural Asante Akyem district in Ghana, we investigated contamination of drinking water with S. enterica to identify a potential source for strains causing invasive blood stream infections in hospitalized febrile children.

Methods

Study site and laboratory procedures

The study was conducted in the rural Asante Akyem District in Ghana, which is the catchment area of the Agogo Presbyterian Hospital (APH), a district hospital with 250 beds. The municipal area has an estimated population of 142,400 inhabitants, spread over an area of 1160 km2. The region has a tropical climate with two rainy seasons from March to June and from September to October and is mainly covered by secondary rain forest and cultivated land. Malaria is highly endemic in this area.

Blood was taken from children aged ≤15 years attending APH with fever (≥38 °C) between September 2007 and November 2012. For microbiological analysis, 1–3 ml venous blood was injected into vials for paediatric blood cultures (Becton Dickinson, NJ 07417, USA) and incubated in an automated BACTEC 9050 instrument (Becton Dickinson). Broth from positive blood culture bottles was examined microscopically (Gram stain) and plated on MacConkey agar, Columbia agar enriched with 5% sheep blood, and chocolate agar (Oxoid, Hampshire, United Kingdom). The following organisms were classified as contaminants: coagulase-negative Staphylococcus spp., Micrococcus spp., Propionibacterium spp., coryneform bacteria and Bacillus spp.

Water samples were collected from 69 villages within the Asante Akyem from October 2009 until December 2009. Water sources considered for sampling were those commonly used by the village populations to collect drinking water, namely wells, rivers, boreholes, outdoor pipes and container-stored water from unknown origin. From the collected water samples, 100 ml was filtered with a 0.45 μm pore cellulose membrane filter (Millipore, Cork, Ireland). The filter was placed into an enrichment broth (Selenite F broth, Oxoid), which was further sub-cultured onto a chromogenic medium (Brilliance Salmonella agar, Oxoid) after 18–24 h incubation at 35–37 °C in normal atmosphere. For the identification of Salmonella spp., the Analytical Profile Index (API 20E) test (bioMerieux, Durham, North Carolina) was performed and confirmed by a Salmonella Latex Test (Oxoid). Serotyping was carried out with standard antisera (SIFIN, Berlin, Germany) according to the White Kauffmann le Minor Scheme. For Salmonella positive samples, two colonies were selected to increase the chance for detecting multiple serovars per sample.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

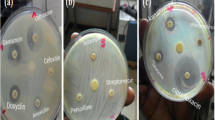

Susceptibility testing was performed using the disk diffusion method (Kirby Bauer) and interpreted using current Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (www.clsi.org). Salmonella isolates were tested for the following antibiotics: ampicillin, ampicillin/sulbactam, ceftriaxone, chloramphenicol, nalidixic acid, cotrimoxazole and tetracycline. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for ciprofloxacin were determined by E-test (Oxoid). Isolates were interpreted as ciprofloxacin susceptible with an MIC ≤0.06 μg/mL, as intermediate (reduced susceptibility) with an MIC < 1 μg/mL and > 0.06 μg/mL and as resistant with an MIC ≥1 μg/mL. Ceftriaxone was used as a screening drug for the detection of extended spectrum beta lactamase (ESBL) producing strains. Salmonella isolates exhibiting resistance to ampicillin, cotrimoxazole, and chloramphenicol were classified as multidrug resistant (MDR).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were applied to show variable distribution amongst blood and water samples. Observations with missing values were not excluded from the analysis, thus possibly resulting in different denominators. Results were presented for blood and water samples separately and were finally compared. All analyses were conducted using Stata Statistical Software 14 (College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

Results

Bacterial bloodstream infections

Blood culture samples were collected from 2720 patients of whom 1255 (45%) were females. Median age of all study children was 2 years (IQR: 0–4) and children positive for S. enterica had a median age of 2 (IQR: 1–3). Two hundred forty-one (9%) positive blood cultures were classified as contaminants and excluded from the analysis. Pathogenic bacteria were isolated from the remaining 382 (14%) positive blood cultures, with S. enterica being the most frequently detected bacterial species (n = 222, 58%). Within S. enterica, 165 (43%) NTS and 57 (15%) S. Typhi were isolated. The three most common NTS serovars were S. Typhimurium (n = 115; 70%), S. Enteritidis (n = 13; 8%) and S. Dublin (n = 8; 5%; Table 1).

Antimicrobial susceptibility

Ninety-five (58%) NTS strains exhibited MDR (Table 2). All strains were sensitive to ceftriaxone, thus testing for ESBL-producing Salmonella strains was not performed. Reduced ciprofloxacin susceptibility was confined to five S. Enteritidis and one S. Typhimurium strain.

Water analysis

The majority of water samples were collected from wells (n = 249; 49%), followed by container-stored water of unknown sources (n = 136; 27%) (Table 2).

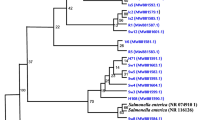

S. enterica was isolated from 19 (4%) water samples. While samples from rivers had the highest Salmonella contamination (n = 8; 15%), no Salmonella were isolated from pipe or borehole samples. Amongst the 19 Salmonella positive water samples, 22 Salmonella isolates were identified. Three of the samples contained two different Salmonella serovars. In total, 14 different serovars were found including the following: S. Ajiobo (n = 1), S. Colindale (n = 2), S. Corvallis (n = 1), S. Duisburg (n = 3), S. Georgia (n = 1), S. Kingston (n = 1), S. Mim (n = 1), S. Poona (n = 1), S. Pramiso (n = 1), S. Rovaniemi (n = 1), S. Pasing (n = 1) S. Rubislaw (n = 3), S. Santander (n = 4), and S. Stanleyville (n = 1). Apart from two ampicillin and one cotrimoxazole resistant isolate, all isolates were susceptible to all tested antibiotics.

There was no overlap between the water-derived Salmonella serovars and the iNTS serovars.

Discussion

The results highlight the significance of MDR S. enterica as a major cause of bacterial bloodstream infections in children in rural Ghana and emerging FQ resistance primarily related to S. Enteritidis. The study demonstrates a distinct distribution of Salmonella serovars with no overlaps between human and water-derived samples. Hence, Salmonella frequently found in drinking water are probably not a major source for invasive bloodstream infections in humans. Recent studies from SSA, using Whole Genome Sequencing methods, strongly suggest that Salmonella serovars causing invasive infections in humans have evolved and adapted within specific hosts [16,17,18,19]. These data support the hypothesis that invasive Salmonella infections are rather transmitted within the human population and not originate from zoonotic sources and are therefore less frequently found in the environment.

In addition, improved awareness of gastrointestinal infections and hygiene practices in the study area, might explain the infrequent environmental contamination with human Salmonella strains.

Currently, little information is available from resource poor countries on contamination of Salmonella serovars in water sources, although studies have shown the presence of a large diversity of different serovars in the aquatic environment [20,21,22,23]. The data correlates well with previous studies showing that rather unusual serovars, not-typically encountered in clinical specimens, colonise drinking water sources. This study indicates that contamination with S. enterica is frequent in the Asante Akyem District especially in dug well and river water. Animals such as reptiles may play an important role in the contamination of water sources, as these are known to be carriers of a vast variety and of uncommon serovars [24]. Overall, data on the potential of such strains to cause disease is scarce and was not investigated in this study. However, environmental S. enterica strains might play a significant role in self-limiting gastrointestinal infections not resulting in invasive disease with hospital admissions. Nonetheless, as no stool samples were assessed, this hypothesis remains speculative. Still, it is known that S. enterica found in drinking water may constitute a risk to human health because almost all serovars of S. enterica have the potential to cause illness in man [20].

Furthermore, resistance to locally administered antibiotics was high amongst S. enterica from blood cultures but almost absent amongst isolates from water. This suggests that S. enterica from water samples were not previously or repeatedly exposed to selective drug pressure as a result of previous antimicrobial treatment.

As for Salmonella blood culture isolates, reports across the African continent from studies with similar inclusion criteria have been published, in which the predominance of MDR S. enterica, in particular infections with NTS have been reported [25, 26]. The high frequency of MDR S. Typhimurium and S. Enteritidis in the study presented here confirms the distribution described in the review by Reddy and colleagues [3].

Drawbacks of the study include different collection times of water and blood culture samples complicating interpretation of transmission pathways. In addition, only two individual colonies were selected per sample while several distinct serovars may colonize one water source at the same time. This may have decreased the chance of detecting multiple serovars in one source and hence possible associations. Also, the overall test sensitivity would have increased by testing larger amounts of water and by longitudinal testing. Nevertheless, the Salmonella isolates found in the water samples give a crude estimation of the serovar composition of prevailing strains in the aquatic environment in the study area. Although the sampling strategy cannot be considered as representative, the exemplarily testing at least demonstrates that serovars found in invasive human disease do not play a quantitatively dominating role in local water sources. It, however, remains speculative where the Salmonella serovars found in the water sources predominantly come from and what their potential to cause disease is. These are important questions to be further investigated.

Conclusion

Quantitative relevance of water-associated transmission of iNTS seems unlikely in this study area. Nevertheless, water contamination with S. enterica might play a role in gastrointestinal infections, which should be further examined.

There is an important information gap, which needs to be filled to understand infection reservoirs and transmission pathways of iNTS in order to devise effective management and control strategies. Future studies are required that focus on genome comparisons of human and zoonotic iNTS isolates in order to investigate Salmonella adaptation to the host more thoroughly and possible anthroponotic transmission.

Also MDR and emerging fluorquinolone resistance in S. enterica associated bloodstream infections in children from SSA urge to investigate evidence-based preventive interventions, like hygiene and sanitation measures or vaccines for high-risk populations.

Abbreviations

- APH:

-

Agogo Presbyterian Hospital

- API:

-

Analytical Profile Index

- BNITM:

-

Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine

- CLSI:

-

Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic Acid

- ESBL:

-

Extended spectrum beta lactamase

- FQ:

-

Fluorquinolone

- iNTS:

-

invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella

- IVI:

-

International Vaccine Institute

- KCCR:

-

Kumasi Centre for Collaborative Research in Tropical Medicine

- KNUST:

-

Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology

- MDR:

-

multidrug resistance

- MICs:

-

minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs)

- NTS:

-

non-typhoidal Salmonella

- PFGE:

-

Pulsed-field gel electrophoressis

- SSA:

-

sub-Saharan Africa

References

Lokken KL, Walker GT, Tsolis RM. Disseminated infections with antibiotic-resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella strains: contributions of host and pathogen factors. Pathogens and Diseases. 2016;74(8):fttw103.

Crump JA, Luby SP, Mintz ED: The global burden of typhoid fever. Bulletin World Health Organization 2004, 82(5)346–353.

Reddy EA, Shaw AV, Crump JA. Community-acquired bloodstream infections in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(6):417–32.

Morpeth SC, Ramadhani HO, Crump JA. Invasive non-Typhi Salmonella disease in Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(4):606–11.

Feasey NA, Dougan G, Kingsley RA, Heyderman RS, Gordon MA. Invasive non-typhoid Salmonella disease: an emerging and neglected tropical disease in Africa. Lancet. 2012;379(9835):2489–99.

Laufer AS, Grass J, Holt K, Whichard JM, Griffin PM, Gould LH. Outbreaks of Salmonella infections attributed to beef-US. Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143(9):2003–13.

De Knegt LV, Pires SM, Hald T. Attributing foodborne salmonellosis in humans to animal reservoirs in the European Union using a multi country stochastic model. Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143(6):1175–86.

EFSA. EU summary report on zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks 2014. EFSA J. 2015;13(12):4329.

Mazurek J, Salehi E, Propes D, Holt J, Bannerman T, Nicholson LM, Bunesen M, Duffy R, Moolenaa RL. A multistate outbreak of Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium infection linked to raw milk consumption-Ohio 2003. J Food Prot. 2004;67(10):2165–70.

Varma JK, Greene KD, Ovitt J, Barrett TJ, Medalla F, Angulo FJ. Hospitalization and antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella outbreaks. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:943–6.

Wall PG, Threlfall EJ, Ward LR, Rowe B. Multiresistant Salmonella typhimurium DT104 in cats. A public health problem. Lancet. 1996;17:348–471.

Ward LR, Thelfall J, Smith HR, O'Brien SJ. Salmonella Enteritidis epidemic. Science. 2000;10(287):1753–4.

Kikuvi GM, Ombui JN, Mitema ES. Serotypes and antimicrobial resistance profiles of Salmonella isolates from pigs at slaughter in Kenya. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2010;1;4(4):243–8.

Sibhat B, Molla ZB, Zerhin A, Muckle A, Cole L, Boerlin P, Wilkie E, Perets A, Mistry K, gebreyes WA. Salmonella serovars and antimicrobial resistance profiles in beef cattle, slaughterhouse personnel and slaughterhouse environment in Ethiopia. Zoonoses Public Health. 2011;58(2):102–9.

Tadesse G, Gebremedhin EZ. Prevalence of Salmonella in raw animal products in Ethiopia: a meta-analysis. BMC Research Notes. 2015;8(163)

Okoro CK, Barquist L, Connor TR, Harris SR, Clare S, Stevens MP, Arends MJ, Hale C, Kane L, Pickard DJ, et al. Signatures of adaptation in human invasive Salmonella typhimurium ST313 populations from sub-Sahara Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003611.

Ramachandran G, Perkins DJ, Schmidlein PJ, Tulapurkar ME, Tennant SM. Invasive Salmonella typhimurium ST313 with naturally attenuated flagellin elicits reduced inflammation and replicates within macrophages. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e3394.

Feasey NA, Hadfield J, Keddy KH, Dallman DJ, Jacobs J, Deng X, Wigley P, Barquist L, Langridge GC, Feltwell T, et al. Distinct Salmonella Enteritidis lineages associated with enterocolitis in high-income settings and invasive disease in low-income countries. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1211–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3644.

Kingsley RA, Msefula CL, Thomson NR, Kariuki S, Holt KE, Gordon MA, Harris D, Clarke L, Whitehead S, Sangal V, et al. Epidemic multiple drug resistant Salmonella typhimurium causing invasive disease in sub-Saharan Africa have distinct genotype. Genome Research (letter). 2009;19(12):2279–87.

Catalao-Dionisio LP, Joao M, Ferreiro VS, Fidalgo ML, Garcia Rosado ME, Borrego JJ. Occurrence of Salmonella spp. in estuarine and coastal waters of Portugal. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2000;78(1):99–106.

Baudart J, Lemarchand K, Brisabois A, Lebaron P. Diversity of Salmonella strains isolated from the aquatic environment as determined by serotyping and amplification of the ribosomal DNA spacer regions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66(4):1544–52.

Arvanitidou M, Stathopoulos GA, Constantinidis TC, Katsouyannopoulos V. The occurrence of Salmonella, Campylobacter and Yersinia spp. in river and lake waters. Microbiol Res. 1995;150(2):153–8.

Dekker DM, Krumkamp R, Sarpong N, Frickmann H, Boahen KG, Frimpong M, Asare R, Larbi R, Hagen RM, Poppert S, et al. Drinking water from dug wells in rural Ghana-Salmonella contamination, environmental factors, and genotypes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;27;12(4):3535–46.

Pedersen K, Lassen-Nielsen AM, Nordentoft S, Hammer AS. Serovars of Salmonella from captive reptiles. Zoonoses Public Health. 2009;56(5):238–42.

Bronzan RN, Taylor TE, Mwenechanya J, Tembo M, Kayira K, Bwanaisa L, Njobvu A, Kondowe W, Chalira C, Walsh AL, et al. Bacteremia in Malawian children with severe malaria: prevalence, etiology, HIV coinfection, and outcome. J Infect Dis. 2007;195(6):895–904.

Mtove G, Amos B, von Seidlein L, Hendriksen I, Mwambuli A, Kimera J, Mallahiyo R, Kim DR, Ochiai RL, Clemens JD, Reyburn H, et al. Invasive salmonellosis among children admitted to a rural Tanzanian hospital and a comparison with previous studies. PLoS One. 2010;5(2):e9244.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the children and their guardians who participated in this study and to the personnel at the Agogo Presbyterian Hospital in particular Richard Afrey and the villagers for the provision of water samples. Without their efforts, this research study would not have been possible.

Funding

The publication is based on research funded by the UBS Optimus Foundation and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (OPPGH5231). Serotyping of the clinical Salmonella isolates was funded by the German armed forces, scientific project number 03 K2-S-450709.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DD and JM designed and managed this study. DE supported writing and revising this manuscript. HF, RH, SP helped coordinating serotyping and contributed in writing the manuscript. KYB and MF were involved in water sample collection and performed the preliminary identification of isolates. RK, NGS, prepared and analysed the data. NS, JI, FM,.EOD and YAS and EF supported planning and managing the study in Ghana. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants were informed about the study’s purpose and procedures. Prior to sample collection, written informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of the participating children. Ethical approval for the study was attained from the Committee on Human Research, Publications and Ethics, School of Medical Science, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana and the Institutional Review Board of the International Vaccine Institute (IVI), Seoul, Korea.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Dekker, D., Krumkamp, R., Eibach, D. et al. Characterization of Salmonella enterica from invasive bloodstream infections and water sources in rural Ghana. BMC Infect Dis 18, 47 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-2957-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-2957-4