Abstract

Background

Enterocytozoon bieneusi has been increasingly reported to infect humans and various mammals. Microsporidia cause diarrhea in HIV-infected patients worldwide. PCR amplification and sequencing based on the internal transcribed spacer region have been used to describe the genotypes of E. bieneusi and transmission of microsporidiosis.

Methods

In this study, we examined E. bieneusi infection and genotypes in HIV-positive patients in Guangxi, China. Stool specimens were collected from 285 HIV-positive patients and 303 HIV-negative individuals. E. bieneusi genotypes were characterized using nested PCR and sequencing.

Results

Thirty-three (11.58%) HIV-positive patients were infected with microsporidia, and no infection was found in the 303 healthy controls. Three new genotypes were identified and named as GX25, GX456, and GX458; four known genotypes, PigEBITS7, Type IV/K, D, and Ebpc, were also identified. Our data showed that the positive rate for microsporidia was significantly higher in the rural patients than in the other occupation groups. In addition, the positive rate for microsporidia was significantly higher in the patients who drink unboiled water than in those with other drinking water sources.

Conclusions

Our results will provide baseline data for preventing and controlling E. bieneusi infection in HIV/AIDS patients. Further studies are required to clarify the epidemiology and potential sources of microsporidia. Our study showed that microsporidium infection occurs in the HIV/AIDS patients in Guangxi, China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gastrointestinal infection is a major opportunistic infection in HIV/AIDS patients, and many studies have reported HIV/AIDS patients co-infected with microsporidia. Microsporidia are obligate intracellular parasites that infect a broad range of vertebrates and invertebrates [1,2,3]. They have been increasingly recognized as human pathogens in AIDS patients, and they are mainly associated with life-threatening chronic diarrhea and systemic disease [4, 5]. In 1959, the first human case of microsporidiosis was detected, and reports of immunocompromised patients infected by microsporidia have increased [1, 6, 7]. Among the microsporidial species, Enterocytozoon bieneusi is the most prevalent human pathogenic species [8]. The infection rate of E. bieneusi among HIV patients has been reported to reach up to 50% [9]. Transmission of E. bieneusi may involve person-to-person as well as environmental sources, such as ditch water, especially in developing countries with poor sanitation [10, 11]. In addition, zoonotic transmission of E. bieneusi has been reported worldwide in various mammal hosts, such as livestock, companion animals, birds, and wildlife. Other routes including waterborn, respiratory or sexual infection have also been reported [12,13,14,15,16].

Considerable genetic variation and genotypes exist within E. bieneusi isolates of human and animal origin, and different pathogenic characteristics and host specificity have been found for E. bieneusi [3]. Molecular diagnostic methods, especially methods that genotype and subtype pathogens, have been used to characterize the transmission of E. bieneusi in HIV patients [17,18,19]. The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of the rRNA gene has been extensively used to identify and describe the genotype characteristics and transmission routes of E. bieneusi in humans and animals [20, 21]. To date, more than 204 ITS genotypes have been reported by genotyping analysis, and all the ITS genotypes have been divided into zoonotic (Group 1) and host-specific groups (Groups 2–8) by phylogenetic analysis [22]. Group 1 infects humans and animals, while the other groups are found mostly in specific hosts and wastewater [13, 15, 23]. The presence of the same genotypes of E. bieneusi in both humans and animals indicates potential zoonotic transmission [18, 24]. The molecular epidemiologic characterization of E. bieneusi has become essential, to predict possible sources of transmission and control the transmission routes.

E. bieneusi infection is responsible for 30%–51% of all cases of diarrhea in patients with AIDS [25]. In fact, E. bieneusi has been detected in 11.4% and 18.5% of nonhuman primates in Guangxi, and various zoonotic genotypes were identified [14, 26]. Hence, humans, especially HIV patients in Guangxi, could face the risk of E. bieneusi infection. To date, no studies have been conducted to describe the E. bieneusi infection in HIV or diarrheal patients in Guangxi. In the present study, we aimed to identify the prevalence and genotypes of E. bieneusi in HIV-infected patients and case controls in Guangxi and compare the differences between the two groups by using。PCR and sequence analysis of the ITS locus. In addition, we evaluated the public health significance of E. bieneusi via phylogenetic analysis and analyzed the risk factors for E. bieneusi in the HIV-infected patients on the basis of demographic and clinical data.

Methods

Study population

Between July 2013 and July 2014, stool specimens were collected from 285 HIV-positive patients in Guangxi. Among the patients, 216 (75.8%) were males and 69 (24.2%) were females. Most (76.1%) of the participants were farmers and live in rural areas. Demographic data, education level, presence of diarrhea, infective routes, recent CD4+ cell counts, and potential risk factors related to waterborne and person-to-person routes and marital status were collected from the participants by attending physicians by using a structured questionnaire at the time of enrollment. The demographic data of the two groups are listed in Table 1. In addition, 303 matched HIV-negative controls with similar demographic and socioeconomic backgrounds were enrolled.

Specimen collection and DNA extraction

The fecal specimens were preserved in 2.5% potassium dichromate and stored at 4 °C. Aliquots of the stool specimens were shipped to the laboratory. The specimens were collected from patients with fecal excretion heavier than 200 mg and no less than three events of diarrhea per day. Sufficient samples were collected for DNA extraction and purification with the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The extracted DNA was stored at −30 °C for PCR and was used for E. bieneusi detection and genotyping.

E. bieneusi detection and genotyping

To detect E. bieneusi, a 392-bp fragment of the rRNA gene, including ITS, was amplified using nested PCR [27]. Primers used for PCR amplification of ITS gene were listed in Table 2.The amplified fragments were analyzed using agarose gel electrophoresis, and the positive samples were used for sequencing. Genotypes of E. bieneusi were determined using sequence analysis of the secondary PCR products and named according to the established nomenclature system. The cycling conditions for E. bieneusi were as follows: the primary cycle consisted of 94 °C for 1 min, 35 cycles of 94 °C for 50 s, 56 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 60 s, followed by 72 °C for 10 min, and termination at 4 °C. A second reaction was carried out similarly. Each specimen was analyzed at least three times by PCR with E. bieneusi-positive sample as positive control and nuclease-free water as negative controls in each run, respectively.

DNA sequencing and data analysis

For accurate analysis, all of the genes were amplified at least three times and all PCR-positive products were sequenced in both directions by using the secondary primers with the ABI 3730 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA) and Big Dye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems). ContigExpress was used to evaluate the wave peak and assemble the sequences. All the nucleotide sequences obtained in the present study were searched using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool, aligned with E. bieneusi reference sequences downloaded from GenBank, and analyzed using Clustal X 1.83, MEGA 5 (http://www.megasoftware.net; last accessed in November 2012). Bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates was used to assess the robustness of the clusters. The chi-square test was used for comparisons.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

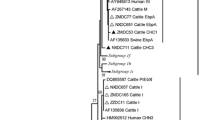

The relationship between the E. bieneusi genotypes identified in this study and other known genotypes deposited in GenBank was inferred using neighbor-joining analysis of the ITS sequences on the basis of genetic distance by the Kimura two-parameter model. The numbers on the branches are percent bootstrapping values from 1000 replicates. Each sequence was identified by its accession number, host origin, and genotype designation.

Unique nucleotide sequences were deposited in GenBank under the following accession numbers: KP718615 (GX458), KP718616 (GX25), and KP718617 (GX456) [see Additional file 1].

Results

Infection rates of E. bieneusi in the participants

Of the 285 fecal specimens from the HIV-positive patients, 33 specimens showed positive results for E. bieneusi after PCR amplification of the ITS locus. The infection rate of E. bieneusi was 11.6% (33/285) in the HIV-positive patients, and E. bieneusi was not found in the HIV-negative patients (Table 1). The differences in the infection rates between the HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients were statistically significant different (χ2 = 37.17, P < 0.01). No age- or sex-associated differences were found in the patients of our study.

Risk factors for microsporidiosis

In the present study, a number of risk factors related to E. bieneusi infection were analyzed, such as gender, age, occupation, water sources, CD4+ cell count, marital status, transmission route, and other risk factors (Table 1). The statistical analysis showed that microsporidium infection was significantly associated with the different occupations of the patients. Farmers showed a higher occurrence of microsporidium infection (14.3%, χ2 = 6.366, P < 0.01) than the other groups with different occupations. In addition, patients who drank unboiled water were more likely to be infected with microsporidia.

Genotypes of E. bieneusi

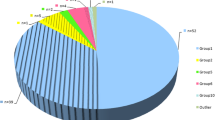

A total of seven ITS genotypes were obtained from 33 successfully sequenced specimens from the HIV-positive patients. Of them, four genotypes have been previously reported, namely, genotype D (11 cases), type IV/K (seven cases), PigEBITS7 (seven cases), and EbpC (four cases) (Table 3). Three new genotypes were found and named as GX25 (one case), GX456 (one case), and GX458 (one case).

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis was performed to understand the genetic relationship among the E. bieneusi genotypes. A neighbor-joining tree was constructed using the published E. bieneusi ITS nucleotide sequences from humans and domestic animals. These new genotypes were phylogenetically related to Group 1, which contains most of the human pathogenic E. bieneusi genotypes (Fig. 1).

Phylogenetic relationship between the Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotype groups. The relationship between the E. bieneusi genotypes identified in this study and other known genotypes deposited in GenBank was inferred using neighbor-joining analysis of ITS sequences on the basis of genetic distance by the Kimura two-parameter model. The numbers on the branches are percentage bootstrapping values from 1000 replicates. Each sequence was identified by its accession number, host origin, and genotype designation. The group terminology for the clusters is based on the study by Zhao et al.(2014). The solid and open circles indicate novel and known genotypes identified in this study, respectively

Discussion

PCR and sequence analysis of the ribosomal ITS are regarded as the standard diagnostic technique for identifying and genotyping E. bieneusi isolates [24]. To date, the infection rate among HIV-infected patients has been reported to reach up to 50% [28], and E. bieneusi causes chronic diarrhea in the patients. In this study, we investigated the prevalence of E. bieneusi infection in HIV-infected patients and HIV-negative controls in Guangxi. High prevalence (11.6%, 33/285) of E. bieneusi was observed in 285 HIV-positive patients, and E. bieneusi was not found in the HIV-negative controls. A previous study conducted on E. bieneusi infection in HIV-positive patients in Henan Province showed that the infection rate was 5.7% (39/683) [29]. The difference in the infection rates between the two provinces in China might be attributed to the overall sample size, composition, and health status of the patients, as well as geographical location. In addition, all of the patients in Wang’s study received highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), while just fewer than half the patients in this study are receiving HAART. In fact, HAART has been reported to reduce the prevalence of microsporidiosis in HIV/AIDS patients in industrialized nations [30, 31].

In the present study, farmers showed a higher occurrence of microsporidium infection (P < 0.01) than the other groups with different occupations. The possible reasons could be the following risk factors: First, the living environment and health conditions in farms are poor when compared with those of the other populations with different occupations. In the countryside, the water used to flush toilets is usually not treated, and many people in these localities do not wash their hands after using the toilet [32]. Therefore, the patients could be infected through fecal-oral transmission. Farmers also have a variety of drinking water sources, such as tap water and pump water, and they provide transmission routes for microsporidia. In fact, a study conducted on the prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections among 463 HIV patients in Benin City, Nigeria, showed that HIV patients who used streams and rivers as sources of water exhibited a significantly higher prevalence of microsporidial infections (P = 0.011) [32]. In this study, the patients who drink unboiled water showed a higher microsporidium infection rate (χ2 = 4.282, P < 0.05) than the other patients. Drinking unboiled water was identified as a risk factor for E. bieneusi infection in the present study, which is consistent with the relatively high occurrence of microsporidia in the farmers.

E. bieneusi is a major human pathogen associated with chronic diarrhea in HIV-infected patients [33,34,35]. In a cross-sectional study of zoonotic E. bieneusi genotypes in HIV-positive patients on antiretroviral therapy, E. bieneusi infection was significantly associated with the occurrence of diarrhea [29]. However, there was no correlation between E. bieneusi infection and the clinical symptoms of the HIV-positive patients, which could be mostly attributed to the immune status of the patients and sampling time. In fact, previous studies have found no association between the intensity of microsporidium infection and clinical symptoms [36, 37]. In our study, some other risk factors (age, gender, CD4+ level, etc.) and clinical manifestations (diarrhea, white blood cell level, etc.) were also analyzed. However, no correlation was found between these risk factors and E. bieneusi infection. Although E. bieneusi is nowadays considered to be an opportunistic pathogen in HIV-infected patients or organ transplant recipients, E. bieneusi infections have been found in HIV-negative, immunocompetent, and other healthy people [38,39,40,41]. In our previous study, E. bieneusi was detected using nested PCR in 34 (13.49%) fecal samples from patients with clinical diarrhea in Shanghai [42]. Therefore, detection of E. bieneusi is absolutely imperative for HIV-infected patients and individuals with clinical diarrhea.

In this study, three new genotypes and four known E. bieneusi genotypes were identified. The new genotypes, namely, GX25 (one case), GX456 (one case), and GX458 (one case), are phylogenetically related to Group 1, which contains most of the human pathogenic E. bieneusi genotypes. Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis of the E. bieneusi isolates on the basis of sequences of the ITS region revealed that the three new genotypes have a high homology with the isolates from pigs (AF135832) [43, 44], indicating their public health significance. The prevalent genotypes were D (11 cases), type IV/K (seven cases), PigEBITS7 (seven cases), and EbpC (four cases). The most frequently observed genotype, D (n = 11), has a large variety of hosts and geographic range. It was first detected in humans in Germany then in American, Asian, and African countries [33, 45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. In fact, genotype D has been identified in HIV patients [29], animals [15, 26], and wastewater [13] in China. Type IV/K has been detected in HIV patients and non-human primates in Henan Province [29] and cats and dogs in Heilongjiang Province [14]. PigEBITS7, previously found in only pigs [55], has been found in humans [29, 56] and monkeys [15]. EbpC has been detected in HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients [29], pigs [57], and wastewater [13] in China (Table 4). The occurrence of the above-mentioned ITS genotypes in the HIV-positive patients of our study suggest the possibility of zoonotic transmission. This is also supported by the fact that genotype D has been detected in animals in Guangxi [15], and further molecular studies with a large sample size and extensive epidemiological information on humans, animals, and water sources are required to better explain the zoonotic transmission of microsporidiosis.

Conclusions

In summary, our study showed the occurrence of microsporidium infection in HIV/AIDS patients in Guangxi, China. The positive rate for microsporidia was significantly higher in the HIV/AIDS patients than in the controls. The four known genotypes indicated that zoonotic transmission of E. bieneusi is possible, suggesting that public health education should be provided to prevent and control zoonotic diseases. Three new genotypes of E. bieneusi were identified, indicating their public health significance. Our data suggest the possibility of zoonotic transmission of E. bieneusi and an association with poor sanitary conditions. Future studies should focus on epidemiological investigations of E. bieneusi in various hosts and water sources to better understand the transmission dynamics of microsporidiosis by molecular analysis.

Abbreviations

- HAART:

-

Highly active antiretroviral therapy

- ITS:

-

Internal transcribed spacer

References

Schottelius J, Da Costa SC. Microsporidia and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2000;95(Suppl 1):133–9.

Sprague V, Becnel JJ, Hazard EI. Taxonomy of phylum microspora. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1992;18:285–395.

Stentiford GD, Becnel JJ, Weiss LM, Keeling PJ, Didier ES, Williams BAP, et al. Microsporidia – Emergent Pathogens in the Global Food Chain.Trends Parasitol. 2016;32(4):336–348.

Dascomb K, Frazer T, Clark RA, Kissinger P, Didier E. Microsporidiosis and HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;24:290–2.

Desportes-Livage I. Microsporidia and other opportunistic protozoa in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Clin Microbiol Infect. 1996;1:152–3.

Weber R, Bryan RT, Schwartz DA, Owen RL. Human microsporidial infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:426–61.

Matsubayashi H, Koike T, Mikata I, Takei H, Hagiwara SA. Case of Encephalitozoon-like body infection in man. AMA Arch Pathol. 1959;67:181–7.

Mathis A, Weber R, Deplazes P. Zoonotic potential of the microsporidia. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:423–45.

Matos O, Lobo ML, Xiao L. Epidemiology of Enterocytozoon bieneusi infection in Huamns. J Parasitol Res. 2012:981424.

Ojuromi OT, Izquierdo F, Fenoy S, Fagbenro-Beyioku A, Oyibo W, Akanmu A, et al. Identification and characterization of microsporidia from fecal samples of HIV-positive patients from Lagos, Nigeria. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35239.

Bern C, Kawai V, Vargas D, Rabke-Verani J, Williamson J, Chavez-Valdez R, et al. The epidemiology of intestinal microsporidiosis in patients with HIV/AIDS in lima, Peru. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1658–64.

Sparfel JM, Sarfati C, Liguory O, Caroff B, Dumoutier N, Gueglio B, et al. Detection of microsporidia and identification of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in surface water by filtration followed by specific PCR. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1997;78S:44.

Li N, Xiao LH, Wang L, Zhao SM, Zhao XK, Duan LP, et al. Molecular surveillance of Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, and Enterocytozoon bieneusi by genotyping and subtyping parasites in wastewater. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e18099.

da Silva Fiuza VR, Lopes CW, de Oliveira FC, Fayer R, Santin M. New findings of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in beef and dairy cattle in Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2016;216:46–51.

Karim MR, Wang R, Dong H, Zhang L, Li J, Zhang S, et al. Genetic polymorphism and zoonotic potential of Enterocytozoon bieneusi from nonhuman primates in China. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:1893–8.

Galvan AL, Magnet A, Izquierdo F, Fenoy S, Rueda C, Vadillo CF, et al. Molecular characterization of human-pathogenic Microsporidia and Cyclospora cayetanensis isolated from various water sources in Spain: a year-long longitudinal study. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:449–59.

Ojuromi OT, Duan L, Izquierdo F, Fenoy S, Oyibo WA, Del Aguila C, et al. Genotypes of Cryptosporidium spp. and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in Lagos, Nigeria. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2016;64:414–8.

Aissa S, Chabchoub N, Abdelmalek R, Kanoun F, Goubantini A, Ammari L, et al. Asymptomatic intestinal carriage of microsporidia in HIV-positive patients in Tunisia: prevalence, species, and pathogenesis. Med Sante Trop. 2017;27(3):281–285.

Mirjalali H, Mohebali M, Mirhendi H, Gholami R, Keshavarz H, Meamar AR, et al. Emerging intestinal Microsporidia infection in HIV(+)/AIDS patients in Iran: microscopic and molecular detection. Iran J Parasitol. 2014;9:149–54.

Sulaiman IM, Fayer R, Yang C, Santin M, Matos O, Xiao L. Molecular characterization of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in cattle indicates that only some isolates have zoonotic potential. Parasitol Res. 2004;92:328–34.

Santin M, Fayer R. Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotype nomenclature based on the internal transcribed spacer sequence: a consensus. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2009;56:34–8.

Karim MR, Dong H, Yu F, Jian F, Zhang L, Wang R, et al. Genetic diversity in Enterocytozoon bieneusi isolates from dogs and cats in China: host specificity and public health implications. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:3297–302.

Thellier M, Breton J. Enterocytozoon bieneusi in human and animals, focus on laboratory identification and molecular epidemiology. Parasite. 2008;15:349–58.

Santin M, Fayer R. Microsporidiosis: Enterocytozoon bieneusi in domesticated and wild animals. Res Vet Sci. 2011;90:363–71.

Kotler DP, Orenstein JM. Clinical syndromes associated with microsporidiosis. Adv Parasitol. 1998;40:321–49.

Ye J, Xiao L, Li J, Huang W, Amer SE, Guo Y, et al. Occurrence of human-pathogenic Enterocytozoon bieneusi, Giardia duodenalis and Cryptosporidium genotypes in laboratory macaques in Guangxi, China. Parasitol Int. 2014;63:132–7.

Tumwine JK, Kekitiinwa A, Nabukeera N, Akiyoshi DE, Buckholt MA, Tzipori S. Enterocytozoon bieneusi among children with diarrhea attending Mulago hospital in Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;67:299–303.

Gumbo T, Sarbah S, Gangaidzo IT, Ortega Y, Sterling CR, Carville A, et al. Intestinal parasites in patients with diarrhea and human immunodeficiency virus infection in Zimbabwe. AIDS. 1999;13:819–21.

Wang L, Zhang H, Zhao X, Zhang L, Zhang G, Guo M, et al. Zoonotic Cryptosporidium species and Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in HIV-positive patients on antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:557–63.

van Hal SJ, Muthiah K, Matthews G, Harkness J, Stark D, Cooper D, et al. Declining incidence of intestinal microsporidiosis and reduction in AIDS-related mortality following introduction of HAART in Sydney, Australia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:1096–100.

Conteas CN, Berlin OGW, Ash LR, Pruthi JS. Therapy for human gastrointestinal microsporidiosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;63:121–7.

Akinbo FO, Okaka CE, Omoregie R, Dearen T, Leon ET, Xiao L. Molecular epidemiologic characterization of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in HIV-infected persons in Benin City, Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86:441–5.

Saksirisampant W, Prownebon J, Saksirisampant P, Mungthin M, Siripatanapipong S, Leelayoova S. Intestinal parasitic infections: prevalences in HIV/AIDS patients in a Thai AIDS-care centre[J]. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2009;103:573–81.

Schwartz DA, Sobottka I, Leitch GJ, Cali A, Visvesvara GS. Pathology of microsporidiosis - emerging parasitic infections in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996;120:173–88.

Chukwuma C. Microsporidium in AIDS patients: a perspective. East Afr Med J. 1996;73:72–5.

Canning EU, Hollister WS. Enterocytozoon bieneusi (Microspora): prevalence and pathogenicity in AIDS patients. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990;84:181–6.

Clarridge JE, Karkhanis S, Rabeneck L, Marino B, Foote LW. Quantitative light microscopic detection of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in stool specimens: a longitudinal study of human immunodeficiency virus-infected microsporidiosis patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:520–3.

Rabeneck L, Gyorkey F, Genta RM, Gyorkey P, Foote LW, Risser JM. The role of Microsporidia in the pathogenesis of HIV-related chronic diarrhea. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:895–9.

Goetz M, Eichenlaub S, Pape GR, Hoffmann RM. Chronic diarrhea as a result of intestinal microsposidiosis in a liver transplant recipient. Transplantation. 2001;71:334–7.

Metge S, Van Nhieu JT, Dahmane D, Grimbert P, Foulet F, Sarfati C, Bretagne SA. Case of Enterocytozoon bieneusi infection in an HIV-negative renal transplant recipient. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;19:221–3.

Rabodonirina M, Bertocchi M, Desportes-Livage I, Cotte L, Levrey H, Piens MA, Monneret G, Celard M, Mornex JF, Mojon M. Enterocytozoon bieneusi as a cause of chronic diarrhea in a heart-lung transplant recipient who was seronegative for human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:114–7.

Wanke CA, DeGirolami P, Federman M. Enterocytozoon bieneusi infection and diarrheal disease in patients who were not infected with human immunodeficiency virus: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:816–8.

Liu H, Shen Y, Yin J, Yuan Z, Jiang Y, Xu Y, et al. Prevalence and genetic characterization of Cryptosporidium, Enterocytozoon, Giardia and Cyclospora in diarrheal outpatients in China. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:25.

Breitenmoser AC, Mathis A, Burgi E, Weber R, Deplazes P. High prevalence of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in swine with four genotypes that differ from those identified in humans. Parasitology. 1999;118:447–53.

Deplazes P, Mathis A, Muller C, Weber R. Molecular epidemiology of Encephalitozoon cuniculi and first detection of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in faecal samples of pigs. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1996;43:93S.

Breton J, Bart-Delabesse E, Biligui S, Carbone A, Seiller X, Okome-Nkoumou M, et al. New highly divergent rRNA sequence among biodiverse genotypes of Enterocytozoon bieneusi strains isolated from humans in Gabon and Cameroon. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:2580–9.

Leelayoova S, Subrungruang I, Suputtamongkol Y, Worapong J, Petmitr PC, Mungthin M. Identification of genotypes of Enterocytozoon bieneusi from stool samples from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in Thailand. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:3001–4.

Sulaiman IM, Bern C, Gilman R, Cama V, Kawai V, Vargas D, et al. A molecular biologic study of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in HIV-infected patients in lima, Peru. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2003;50:591–6.

Ayinmode AB, Zhang H, Dada-Adegbola HO, Xiao L. Cryptosporidium hominis subtypes and Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in HIV-infected persons in Ibadan, Nigeria. Zoonoses Public Health. 2014;61:297–303.

Mirjalali H, Mirhendi H, Meamar AR, Mohebali M, Askari Z, Mirsamadi E, et al. Genotyping and molecular analysis of Enterocytozoon bieneusi isolated from immunocompromised patients in Iran. Infect Genet Evol. 2015;36:244–9.

Chabchoub N, Abdelmalek R, Breton J, Kanoun F, Thellier M, Bouratbine A, et al. Gnotype identification of Enterocytozoon bieneusi isolates from stool samples of HIV-infected Tunisianpatients. Parasite. 2012;19:147–51.

Wumba R, Longo-Mbenza B, Menotti J, Mandina M, Kintoki F, Situakibanza NH, et al. Epidemiology, clinical, immune, and molecular profiles of microsporidiosis and cryptosporidiosis among HIV/AIDS patients. Int J Gen Med. 2012;5:603–11.

Agholi M, Hatam GR, Motazedian MHHIV. AIDS-associated opportunistic protozoal diarrhea. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2013;29:35–41.

Espern A, Morio F, Miegeville M, Illa H, Abdoulaye M, Meyssonnier V, et al. Molecular study of microsporidiosis due to Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Encephalitozoon intestinalis among human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients from two geographical areas: Niamey, Niger, and Hanoi, Vietnam. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:2999–3002.

Buckholt MA, Lee JH, Tzipori S. Prevalence of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in swine: an 18-month survey at a slaughterhouse in Massachusetts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:2595–9.

Tavalla M, Mardani-Kateki M, Abdizadeh R, Nashibi R, Rafie A, Khademvatan S. Molecular identification of Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Encephalitozoon spp. in immunodeficient patients in Ahvaz, Southwest of Iran. Acta Trop. 2017;172:107–112.

Li W, Diao R, Yang J, Xiao L, Lu Y, Li YS, et al. High diversity of human-pathogenic Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in swine in northeast China. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:1147–53.

Akinbo FO, Okaka CE, Omoregie R, Adamu H, Xiao L. Unusual Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes and Cryptosporidium hominis subtypes in HIV-infected patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89:157–61.

Sarfati C, Bourgeois A, Menotti J, Liegeois F, Moyou-Somo R, Delaporte E, et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasites including microsporidia in human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in Cameroon: a cross-sectional study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:162–4.

Stark D, van Hal S, Barratt J, Ellis J, Marriott D, Harkness J. Limited genetic diversity among genotypes of Enterocytozoon bieneusi strains isolated from HIV-infected patients from Sydney, Australia. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58(Pt 3):355–7.

ten Hove RJ, Van Lieshout L, Beadsworth MB, Perez MA, Spee K, Claas EC, Verweij JJ. Characterization of genotypes of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in immunosuppressed and immunocompetent patient groups. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2009;56(4):388–93. 19602086

Khanduja S, Ghoshal U, Agarwal V, Pant P, Ghoshal UC. Identification and genotyping of Enterocytozoon bieneusi among human immunodeficiency virus infected patients. J Infect Public Health. 2017;10(1):31–40.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Aiqin Liu and Ph.D. Wei Zhao (Department of Parasitology, Harbin Medical University, Harbin, Heilongjiang, China) for assistance in the process of analyzing data.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Special Program for Scientific Research of Public Health of China (No. 201302004 to Y.S., No. 201502021 to J.C.), the Special National Project on Research and Development of Key Biosafety Technologies of China (No.2016YFC1201900 to J.C.), the Guangxi Medical and Health Topics of Self-financing Scheme (No. Z2014155 to Z.J) and the Fourth Round of Three-Year Public Health Action Plan of Shanghai, China (No. 15GWZK0101 to JC). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available in order to protect participant confidentiality.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: YS JC HL and ZJ. Performed the experiments: HL YS ZJ ZY ZW BY DZ. Analyzed the data: YS HL ZJ JC. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: JC YS. Wrote the manuscript: HL ZJ YS JC. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance of this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Parasitic Diseases, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (reference no. 2012–12). The objectives, procedures, and potential risk were orally explained to all the participants. Written informed consent was given and signed by all the participants. Parents/guardians provided consent on behalf of child participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

The data of unique nucleotide sequences. (TXT 1 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, H., Jiang, Z., Yuan, Z. et al. Infection by and genotype characteristics of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in HIV/AIDS patients from Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, China. BMC Infect Dis 17, 684 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2787-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2787-9