Abstract

Background

The rising number of older multimorbid in-patients has implications for medical care. There is a growing need for the identification of factors predicting the needs of older patients in hospital environments. Our aim was to evaluate the use of clinical and functional patient characteristics for the prediction of medical needs in older hospitalized patients.

Methods

Two hundred forty-two in-patients (57.4% male) aged 78.4 ± 6.4 years, who were consecutively admitted to internal medicine departments of the University Hospital Essen between July 2015 and February 2017, were prospectively enrolled. Patients were assessed upon admission using the Identification of Seniors at Risk (ISAR) screening followed by comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA). The CGA included standardized instruments for the assessment of activities of daily living (ADL), cognition, mobility, and signs of depression upon admission. In multivariable regressions we evaluated the association of clinical patient characteristics, the ISAR score and CGA results with length of hospital stay, number of nursing hours and receiving physiotherapy as indicators for medical needs. We identified clinical characteristics and risk factors associated with higher medical needs.

Results

The 242 patients spent [median(Q1;Q3)]:9.0(4.0;16.0) days in the hospital, needed 2.0(1.5;2.7) hours of nursing each day, and 34.3% received physiotherapy.

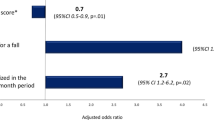

In multivariable regression analyses including clinical patient characteristics, ISAR and CGA domains, the factors age (β = − 0.19, 95% confidence interval (CI) = − 0.66;-0.13), number of admission diagnoses (β = 0.28, 95% CI = 0.16;0.41), ADL impairment (B = 6.66, 95% CI = 3.312;10.01), and signs of depression (B = 6.69, 95% CI = 1.43;11.94) independently predicted length of hospital stay. ADL impairment (B = 1.14, 95%CI = 0.67;1.61), cognition impairment (B = 0.57, 95% CI = 0.07;1.07) and ISAR score (β =0.26, 95% CI = 0.01;0.28) independently predicted nursing hours. The number of admission diagnoses (risk ratio (RR) = 1.06, 95% CI = 1.04;1.08), ADL impairment (RR = 3.54, 95% CI = 2.29;5.47), cognition impairment (RR = 1.77, 95% CI = 1.20;2.62) and signs of depression (RR = 1.99, 95% CI = 1.39;2.85) predicted receiving physiotherapy.

Conclusion

Among older in-patients at risk for functional decline, the number of comorbidities, reduced ADL, cognition impairment and signs of depression are important predictors of length of hospital stay, nursing hours, and receiving physiotherapy during hospital stay.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

With the ongoing demographic changes, hospitals face a constantly rising number of older, often multimorbid patients. This has profound implications for patient care [1,2,3,4]. Older patients with multimorbidity are characterized by multidimensional impairments including physiological, emotional, social, and cognitive deficits, which are associated with higher risk of functional decline [3, 5,6,7]. Older patients with chronic and complex conditions are more vulnerable and likely to fall, and have a higher number of risk factors which could extend and complicate their hospital stay and exacerbate complications [1, 8]. Since the number of such patients at risk is expected to increase due to demographical changes, attempts have been made to identify these patients using screenings and assessments [9, 10]. By now the ISAR screening tool is one of the most commonly used tools to predict the risk of functional decline in older patients [6, 11, 12]. For high-risk patients with positive ISAR screening a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) is recommended as a second diagnostic step. The ISAR screening in combination with the CGA has recently been validated for acute medical departments by Scharf et al. [13]. Since the CGA is a time- and resource consuming assessment it is not efficient to perform CGA in all patients [14, 15]. In patients at risk for functional decline, the CGA enables caregivers to collect further information about patients’ clinical and functional characteristics and offers a possibility to gain a better understanding of mechanisms underlying needs for intensified in-hospital medical care [16].

The need of intensified medical care in older patients as reflected by prolonged length of hospital stay, more nursing hours and patients receiving physiotherapy challenges personnel and financial resources [8, 17, 18]. Previous studies have shown that prolonged length of hospital stay is predicted by factors including female sex and polypharmacy in patients aged ≥65 years admitted to acute internal and geriatric wards [8] and by age ≥ 60 and higher number of comorbidities in colon cancer patients aged < 60 to > 80 years [19]. Thus far, it is unknown which patient characteristics predict prolonged length of hospital stay in older internal medicine in-patients who are at risk for functional decline defined by a positive ISAR.

An association between nursing hours and patients’ functional status seems obvious but systematic evidence-based analyses are still scarce [20]. A study conducted by Sousa et al. found that nursing hours in intensive care patients were predicted by higher age and severity of illness and it were higher in surgical patients than in patients in internal medicine wards [21]. In patients admitted to surgery wards, comorbidities, the ISAR score, mobility impairment, ADL impairment and cognition impairment were predictors of nursing hours [6]. Evidence for the prediction of nursing hours in internal medicine in-patients is still missing as is evidence for the prediction of physiotherapy, which reflects mobility impairment and also contributes to functional recovery, in internal medicine in-patients. Previous studies evaluated how physiotherapy influenced patients’ medical needs [22, 23]. The association of physiotherapy with preexisting impairment was much less studied [24, 25].

There have hitherto been very few studies exploring higher medical needs in older patients at risk for functional decline. To further improve the process by which greater medical care is granted to certain patients, we need to understand which patient characteristics are associated with patient’s needs for intensified medical care in hospital environments. In our last manuscript, we evaluated the diagnostic validity of the ISAR score and the CGA conducting cutoff- and sensitivity/specificity analyses [13]. We now focus on the clinical application of these tools and study how patient characteristics, the ISAR score and CGA results are associated with length of hospital stay, nursing hours, and receiving physiotherapy in older internal medicine patients.

Methods

Study cohort

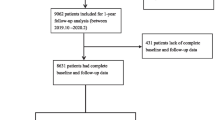

The sample used for the present analyses included 242 hospitalized patients (57.2% male, mean ± standard deviation (SD) age 78.4 ± 6.4 years old) who were admitted electively or via emergency department to the internal medicine departments of the University Hospital Essen between July 2015 and February 2017 and who received ISAR screening by the nursing staff upon admission. Patients were included into the present study if they fulfilled an age criterion (see below) and received a positive ISAR screening (score ≥ 2) followed by CGA (Fig. 1) conducted by the nursing staff upon admission. The age criterion was a) ≥75 years for patients in the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology and in the Department of Cardiology and Angiology or b) ≥65 years for patients in the Department of Nephrology since nephrological patients exhibit premature aging [26, 27]. The CGA was performed within 3 days after admission by a geriatric liaison service (consisting of a geriatrician, a psychologist and an occupational therapist). The available data were obtained prospectively. More detailed information about study cohort characteristics and methodology have previously been reported (see [13]). The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University Duisburg-Essen and need for consent was waived.

Clinical and functional characteristics of patients

Clinical characteristics

It has been proposed that admission diagnoses represent the best predictor for length of hospital stay [28]. Since we had a broad spectrum of different internal medicine diseases, we analyzed the number of admission diagnoses as an indicator of illness severity). Patients’ demographic data, diagnoses and medical histories were taken from the electronical Hospital Information System (HIS).

Functional characteristics: ISAR screening

We utilized a modified version of the original ISAR by McCusker [29]. This ISAR screening comprises six yes/no items about the following domains: Premorbid functional dependence, acute change in functional dependence within the last 24 h, hospitalization within the last 6 months, impaired vision, impaired memory and polypharmacy (≥6 medications). These items are summed up resulting in an ISAR score ranging from 0 to 6. An ISAR score ≥ 2 was interpreted as positive implying that patients with positive ISAR are at risk for functional decline.

Functional characteristics: CGA

The CGA included six commonly used geriatric tests. The Barthel Index was used for the assessment of ADL with a score ≤ 90 defined as impaired [30,31,32]. The Timed Up and Go [33] and the Tinetti Mobility Test [34] were used for the assessment of mobility. Mobility was rated as impaired if Timed Up & Go was ≥20 s and/or the patients had scores < 20 on the Tinetti Mobility Test [35, 36]. Cognition was assessed using the 30 item Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [37] and the Clock-Drawing Test [38]. Cognition was interpreted as impaired if MMSE was ≤27 and/ or the clock-Drawing Test score was ≥3 [39, 40]. For the assessment of signs of depression, we applied the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). A GDS score ≥ 6 was interpreted as the presence of signs of depression [41].

In-hospital medical needs

Measures of in-hospital medical needs comprised length of hospital stay in days, nursing hours per day and received physiotherapy (yes/no), which were retrieved from the electronical HIS. Length of hospital stay was defined as the number of days from admission to discharge from the ward. Prolonged length of hospital stay was defined as ≥7 days, which is the minimum duration of geriatric rehabilitation in Germany. Nursing hours were documented using the “Leistungserfassung in der Pflege” catalogue, a set of approximately 180 items covering all features of in-patient nursing care which is widely used in German-speaking countries [20]. Each item includes a time value, which is coded as the default value or adapted based on nursing effort (for further details see [6]). More nursing hours were defined as ≥2 h per day as this was the median in our cohort. Receiving physiotherapy was again operationalized using the HIS data. Since 159 (65.7%) patients did not receive physiotherapy, the variable was dichotomized into receiving physiotherapy and not receiving physiotherapy.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD for normally distributed data (age) or as median and interquartile range (Q1;Q3) when data was not normally distributed (all other variables). Categorical variables were shown as numbers and percentages (%). We determined the sample size using the sample size calculator G*Power [42] (see Additional file 1: supplemental material S1).

We dichotomized patients’ outcome variables into

-

(a)

length of hospital stay <7 days vs ≥7 days,

-

(b)

nursing hours above median (≥2 hours) vs below median (<2 hours), and

-

(c)

receiving physiotherapy vs not receiving physiotherapy

To compare these characteristics between patients with low and high medical needs, we used t-tests for normally distributed continuous data, Mann-Whitney-U-tests for data that was not normally distributed and χ2 tests for categorical data.

To evaluate the predictors for length of hospital stay in days and nursing hours per day, unadjusted univariable and adjusted multivariable linear regressions (forced entry method) were calculated. Since only about one third of patients (34.3%) received physiotherapy during hospital stay, we used the dichotomized variable of receiving physiotherapy (yes vs no) in uni- and multivariable Poisson regressions with robust error variance. The factors age, sex, number of admission diagnoses, ISAR score, ADL, mobility impairment and cognition impairment as well as signs of depression were first inserted unadjusted into univariable linear and univariable Poisson regressions. In a next step we analyzed the effects of the following models on in-hospital medical needs (length of hospital stay, nursing hours, and receiving physiotherapy).

-

(a)

Model 1 including the ISAR score adjusted for age and sex

-

(b)

model 2 including CGA domains (mobility impairment, cognition impairment, signs of depression and ADL impairment) adjusted for age and sex,

-

(c)

model 3 including CGA domains (as above) and the ISAR score adjusted for age and sex and

-

(d)

model 4 including CGA domains (as above), ISAR score, and number of admission diagnoses adjusted for age and sex.

In regression analyses, missing data were excluded list-wise, while in the other calculations, cases were only excluded if outcome variables were missing. All analyses were performed using Statistical Package for Social Science 22 (SPSS 22) for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, U.S.A.).

Results

Study cohort

The 242 patients of the total cohort (78.4 ± 6.4 years and 57.2% male) spent 9.0(4.0; 16.0) (median(Q1;Q3)) days in hospital, and received 2.0(1.5;2.7) hours of nursing each day. Approximately one third (34.3%) received physiotherapy. Of the total cohort, 48.8% had chronic kidney disease, 38.8% had cancer, and 39.7% had coronary heart disease. ADL impairment was present in 47.1%, mobility impairment in 35.1%, cognition impairment in 53.7%, and signs of depression in 11.6% of the total cohort. Further demographic and medical data including comorbidities for the total cohort and split by high and low medical needs are shown in Table 1 and Additional file 1: supplemental material S2.

Factors associated with needs for intensified medical care

Length of hospital stay

Comparison of patients staying < 7 vs ≥7 days in hospital

142 (58.7%) of the patients stayed for ≥7 days in hospital. Compared with patients staying < 7 days (n = 100), patients who stayed for ≥7 days were significantly more often female (47.9% vs 35.0%, p = 0.046) had a higher number of diagnoses at admission (median(Q1;Q3) = 2.0(2.0;6.0) vs 1.0(1.0;6.0), p < 0.001), received more nursing hours (2.1(1.6;2.9) vs 1.9(1.4;2.6), p < 0.001), and more often received physiotherapy (53.5% vs 7.0%, p < 0.001). They were also more often impaired in the CGA domains ADL (55.6% vs 47.1%, p = 0.002), mobility (41.5% vs 26.0%, p = 0.012), signs of depression (15.5% vs 6.0%, p = 0.022) with a tendency towards significance in cognition (58.5% vs 47.0%, p = 0.071). Age and the ISAR score did not significantly differ between patients staying ≥7 days and patients staying < 7 days (Table 1).

Predictors of length of hospital stay in multivariable regression models

In unadjusted regression analyses, younger age (β = − 0.19, 95% CI = -0.66;-0.13), higher number of admission diagnoses (β = 0.28, 95% CI = 0.16;0.41), ADL impairment (B = 6.66, 95% CI = 3.31;10.01) and signs of depression (B = 6.69, 95% CI = 1.43;11.94) were significantly associated with longer hospital stay in the total cohort. In a multivariable regression including the ISAR score, age and sex, only younger age remained a significant predictor (model 1 in Table 2). Replacing the ISAR with CGA results, ADL impairment and cognition impairment as well as signs of depression were associated with longer hospital stay in addition to younger age (model 2 in Table 2). The addition of the ISAR score did not influence regression model characteristics to a relevant degree (model 3 in Table 2) whereas further adding the number of admission diagnoses (model 4 in Table 2) improved the regression model from R2 = 0.143 to 0.197. That is, because a higher number of admission diagnoses was a significant predictor of longer hospital stays, as were ADL impairment, cognition impairment, signs of depression and younger age.

Nursing hours per day

Comparison of patients needing < 2 vs ≥2 h nursing per day

108 (50.9%) of the patients received ≥2 h of nursing per day. Compared with patients receiving < 2 h of nursing per day; patients with more nursing hours (≥2 h per day) more often had a diagnosis of dementia (13.0% vs 3.8%, p = 0.017), diagnosis of depression (9.3% vs 1.0%, p = 0.006), and diagnosis of pressure ulcer (11.1% vs 3.8%, p = 0.045. They also more often received physiotherapy (44.4% vs 24.0%, p = 0.002), had a higher ISAR score (3.0(2.0;4.0) vs 2.0(2.0;3.0), p = 0.002), and more often hadADL impairment (61.1% vs 33.7%, p < 0.001) and mobility impairment (42.6% vs 29.8%, p = 0.046). These two groups did not differ in age, number of admission diagnoses, and the CGA domains mobility, cognition, and signs of depression (Table 1).

Predictors of nursing hours in multivariable regression models

In unadjusted regression analyses, a higher ISAR score (β = 0.26, 95% CI = -0.01; 0.28), ADL impairment (B = 1.14, 95% CI = 0.67;1.61) and cognition impairment (B = 0.57, 95% CI = 0.07;1.07) were significant predictors of hours of nursing care received per day. In multivariable regression models, only ADL impairment remained a significant predictor (models 1–4 in Table 3).

Receiving physiotherapy

Comparison of patients receiving physiotherapy vs not receiving physiotherapy

83 patients (34.3%) received physiotherapy, whereas 159 patients did not. Compared with patients not receiving physiotherapy, patients receiving physiotherapy had pressure ulcers more often (12.0% vs 5.0%, p = 0.048). Patients who received physiotherapy stayed in hospital for longer (20.0 vs 6.0 days, p < 0.001), needed more hours of nursing (2.6(1.9;3.3) vs 1.8(1.4;2.5), p = 0.044), were female more often (47.0% vs 37.1%,p = 0.018) and had a higher ISAR score (3.0 (2.0;4.0), p = 0.040). Patients who received physiotherapy were also more often impaired in ADL (75.9% vs 32.1%, p < 0.001), mobility (45.8% vs 29.6%, p = 0.009), cognition (66.3% vs 47.2%, p = 0.029), more often showed signs of depression (20.5% vs 6.9%, p = 0.045) and had a higher number of admission diagnoses (3.0 (1.0;7.0) vs 1.0(1.0;2.0), p < 0.001). Age did not differ between these groups (Table 1).

Predictors of receiving physiotherapy in multivariable regression models

In unadjusted regressions, a higher number of admission diagnoses (RR = 1.06, 95% CI = 1.04;1.08), ADL impairment (RR = 3.54, 95% CI = 2.29;5.47), cognition impairment (RR = 1.77, 95% CI = 1.20;2.62), and signs of depression (RR = 1.99, 95% CI = 1.39;2.85) were significant predictors of receiving physiotherapy (Table 4). In a multivariable regression including age, sex and the ISAR score, only female sex remained a significant predictor (model 1 in Table 4). When replacing the ISAR with CGA results, ADL impairment and signs of depression were significantly associated with receiving physiotherapy (model 2 in Table 4). The addition of the ISAR score again did not influence regression model characteristics to a high degree (model 3 in Table 4). Further addition of the number of medical admission diagnoses (model 4 in Table 4) improved the regression model from R2 = 0.291 to 0.336. In addition to ADL impairment a higher number of admission diagnoses was a significant predictor of receiving physiotherapy with cognition impairment reaching significance now, as well. In contrast, signs of depression stayed slightly below the threshold of statistical significance (model 4 in Table 4) presumably because of a significant intercorrelation between number of admission diagnoses and signs of depression.

Discussion

The present study identified predictors of medical needs represented by length of hospital stay, nursing hours and receiving physiotherapy in older hospitalized patients at risk for functional decline identified by a positive ISAR. In multivariable regressions, significant predictors of length of hospital stay were ADL impairment and cognition impairment as well as signs of depression, in addition to a higher number of admission diagnoses. Patients with more nursing hours (≥2 h) more often had a diagnosis of dementia and depression, as well as ADL impairment and mobility impairment than patients with < 2 h of nursing per day. Moreover, ADL impairment was a significant predictor of nursing hours per day in multivariable regressions. Predictors of receiving physiotherapy in multivariable regressions were a higher number of admission diagnoses and ADL impairment, whereas cognition impairment and signs of depression, were significant predictors in unadjusted univariate regression models.

Comparison with literature

Length of hospital stay

In our study, the median length of hospital stay in the total cohort was 9.0 (4.0;16.0) days which is comparable to other older patient cohorts. The median stay in hospital was between 5 and 14 days in older patients admitted to geriatric and internal medicine wards [8, 17, 22, 43, 44]. In a previous study analyzing 419 patients aged ≥70 years from geriatric wards [28], higher age, number of admission diagnoses, incontinence, and ADL impairment predicted a longer hospital stay. In a cohort of older orthopedics and trauma surgery patients (82.5 ± 5.5 years) impairment of ADL, signs of depression, and a higher number of admission diagnoses predicted a longer hospital stay [6].

Available data concerning the predictive value of cognition impairment for length of hospital stay is ambiguous. Vetrano et al. showed that cognition impairment assessed by the MMSE did not predict the length of hospital stay in older patients (≥65 years) electively admitted to acute geriatric and internal medicine wards in Italy [8]. However, other studies showed that cognitive impairment or the diagnosis of dementia predicted a longer hospital stay [45, 46]. Binder and Robins showed that a lower MMSE score was a significant predictor of a longer hospital stay. A decline in the MMSE score over 1 year in community-dwelling older persons was associated with an higher risk of hospitalization and longer hospital stay (> 20 days) [47]. Cognitive impairment often remains undetected in hospitals. However, early identification of cognitive impairment while in the hospital is crucial since patients with cognitive impairment are often malnourished, have a greater risk of falls, higher mortality, longer hospital stay, and higher short-term readmission risk [48]. Besides cognition impairment, signs of depression were associated with a longer hospital stay in our study. In a meta-analysis, Jansen et al. described that patients with comorbid depression spent more days in hospital (mean 13.8 days) than patients without comorbid depression (mean 10.5 days) and that comorbid depression was also related to increased medical costs which was not further analyzed in their meta-analysis due to limited data [49].

Nursing

There is only limited research on how to predict nursing workload [50]. In a study with results comparable to the results of our study, conducted by Mueller et al. analyzing 50 geriatric patients in multivariable analyses, impairment of ADL measured by the Barthel Index was a highly significant predictor of nursing hours [20]. In a Canadian Multicenter study of Hall et al., hospitalized patients of internal medicine, as well as surgical and obstetric wards needed more nursing hours per day if they were older or if they suffered from more complex diseases, both of which were not associated with nursing hours in our cohort [51]. In our internal medicine patients, an impaired Barthel Index for the assessment of ADL was the only significant predictor of nursing workload and is therefore a useful tool for predicting older patients’ needs. One explanation for the influence of the Barthel Index in predicting nursing hours is that the Barthel Index is closely linked to the nursing anamnesis at the beginning of the nursing process, which includes planning how to address patients’ nursing needs and accordingly allocate nursing hours.

Physiotherapy

Receiving physiotherapy was also predicted by impairment in ADL and signs of depression in our internal medicine patients at risk for functional decline. Physicians prescribe physiotherapy for patients with ADL impairment because physiotherapy aims to restore the patients’ functional independence [52]. One explanation for the impact of depression could be that the prescription of physiotherapy was also based on the idea that the patient would benefit from physiotherapy because of its influence on mood [53]. Another explanation could be that depressed patients better vocalize their needs.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of this study was the prospective design and combination of clinical and functional patient characteristics, which allows the analysis of associations between clinical patient characteristics and the patients’ medical needs. We included a broad spectrum of internal medicine diseases and merged patients from cardiology, gastroenterology, and nephrology departments. By merging patients from different wards, we decreased the susceptibility of our data to local department specificities.

Since we only included internal medicine patients, our results should be transferred carefully to other medical specialties. In a German orthopedics and trauma surgery department, ADL impairment and signs of depression predicted length of hospital stay. Impairments in ADL and cognition and a higher ISAR score predicted nursing hours per day, and impairments in ADL and mobility predicted received physiotherapy [6]. This slightly different combination of predictors compared to our internal medicine patient cohort underline the importance of performing a full CGA that covers a variety of domains. Our study evaluated a group at particularly high risk for functional decline, which suffers from a broad range of medical problems. Further efforts will be needed to test the observations made in other medical environments [54, 55]. Our study evaluated medical needs in a university hospital environment. Further analyses are required to show if the identified risk factors can also predict medical needs in non-academic primary hospitals.

According to our sample size calculation (see Additional file 1: supplemental material S1), the cohort of 242 patients allowed us to perform regression analyses using eight predictors. Of the 318 patients evaluated for eligibility, a CGA could not be performed in 76 patients due a variety of reasons that comprised language barriers, lack of consent, or rapid hospital discharge. Therefore, our results may not be representative for patients with short hospital stays. The combination of clinical and functional patient characteristics was an additional strength of our study. We performed an extensive CGA in every patient which we combined with clinical routine data. Of course, CGA itself can influence medical care and change patients’ outcome e.g. by raising awareness of the patients’ medical needs and increasing the attention of the hospital staff. Using data of the HIS implies that data documentation is complete and adequate.

Conclusion

Among older in-patients at risk for functional decline, the number of comorbidities, ADL impairment, cognition impairment, and signs of depression are important predictors of medical needs during hospital stay. Patients in needs of intensified medical care should be identified soon after admission. Their early identification enables appropriate care and treatment allocation.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data are included in the paper. If additional data is needed it can be made available via the ethics committee of the University Duisburg-Essen (ethikkommission@uk-essen.de) to researchers meeting the criteria for confidential data access.

Abbreviations

- ADL:

-

Activities of daily living

- CGA:

-

Comprehensive geriatric assessment

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- GDS:

-

Geriatric Depression Scale

- HIS:

-

Hospital information system

- ISAR:

-

Identification of Seniors at Risk screening

- MMSE:

-

Mini Mental State Examination

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SPSS 22:

-

Statistical Packing for Social Science 22

References

Ellis G, Gardner M, Tsiachristas A, Langhorne P, Burke O, Harwood RH, Conroy SP, Kircher T, Somme D, Saltvedt I, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9:Cd006211.

Aaldriks AA, van der Geest LGM, Giltay EJ, le Cessie S, Portielje JEA, Tanis BC, Nortier JWR, Maartense E. Frailty and malnutrition predictive of mortality risk in older patients with advanced colorectal cancer receiving chemotherapy. J Geriatr Oncol. 2013;4(3):218–26.

Etman A, Burdorf A, Van der Cammen TJM, Mackenbach JP, Van Lenthe FJ. Socio-demographic determinants of worsening in frailty among community-dwelling older people in 11 European countries. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(12):1116–21.

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet (London, England). 2013;381(9868):752–62.

Rosted E, Schultz M, Dynesen H, Dahl M, Sorensen M, Sanders S. The identification of seniors at risk screening tool is useful for predicting acute readmissions. Dan Med J. 2014;61(5):A4828.

Gronewold J, Dahlmann C, Jäger M, Hermann DM. Identification of hospitalized elderly patients at risk for adverse in-hospital outcomes in a university orthopedics and trauma surgery environment. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0187801.

Amblàs-Novellas J, Martori JC, Espaulella J, Oller R, Molist-Brunet N, Inzitari M, Romero-Ortuno R. Frail-VIG index: a concise frailty evaluation tool for rapid geriatric assessment. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):29.

Vetrano DL, Landi F, De Buyser SL, Carfì A, Zuccalà G, Petrovic M, Volpato S, Cherubini A, Corsonello A, Bernabei R, et al. Predictors of length of hospital stay among older adults admitted to acute care wards: a multicentre observational study. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25(1):56–62.

Apostolo J, Cooke R, Bobrowicz-Campos E, Santana S, Marcucci M, Cano A, Vollenbroek-Hutten M, Germini F, Holland C. Predicting risk and outcomes for frail older adults: an umbrella review of frailty screening tools. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2017;15(4):1154–208.

Vergara I, Mateo-Abad M, Saucedo-Figueredo MC, Machon M, Montiel-Luque A, Vrotsou K, Nava Del Val MA, Diez-Ruiz A, Guell C, Matheu A, et al. Description of frail older people profiles according to four screening tools applied in primary care settings: a cross sectional analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):342.

Galvin R, Gilleit Y, Wallace E, Cousins G, Bolmer M, Rainer T, Smith SM, Fahey T. Adverse outcomes in older adults attending emergency departments: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the identification of seniors at risk (ISAR) screening tool. Age Ageing. 2017;46(2):179–86.

Singler K, Heppner HJ, Skutetzky A, Sieber C, Christ M, Thiem U. Predictive validity of the identification of seniors at risk screening tool in a German emergency department setting. Gerontology. 2014;60(5):413–9.

Scharf A-C, Gronewold J, Dahlmann C, Schlitzer J, Kribben A, Gerken G, Rassaf T, Kleinschnitz C, Dodel R, Frohnhofen H, et al. Health outcome of older hospitalized patients in internal medicine environments evaluated by identification of seniors at risk (ISAR) screening and geriatric assessment. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):221.

Maas HA, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Rikkert MGO, Wymenga AM. Comprehensive geriatric assessment and its clinical impact in oncology. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(15):2161–9.

Stuck AE, Siu AL, Wieland GD, Rubenstein LZ, Adams J. Comprehensive geriatric assessment: a meta-analysis of controlled trials. Lancet. 1993;342(8878):1032–6.

Wolinsky FD, Johnson RJ. The use of health services by older adults. J Gerontol. 1991;46(6):S345–57.

Mould-Quevedo JF, García-Peña C, Contreras-Hernández I, Juárez-Cedillo T, Espinel-Bermúdez C, Morales-Cisneros G, Sánchez-García S. Direct costs associated with the appropriateness of hospital stay in elderly population. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9(1):151.

Rowe JW, Fulmer T, Fried L. Preparing for better health and health Care for an Aging Population. Jama. 2016;316(16):1643–4.

Kelly M, Sharp L, Dwane F, Kelleher T, Comber H. Factors predicting hospital length-of-stay and readmission after colorectal resection: a population-based study of elective and emergency admissions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):77.

Mueller M, Lohmann S, Strobl R, Boldt C, Grill E. Patients' functioning as predictor of nursing workload in acute hospital units providing rehabilitation care: a multi-Centre cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:295.

CRd S, Gonçalves LA, Toffoleto MC, Leão K, Padilha KG. Predictors of nursing workload in elderly patients admitted to intensive care units. Revista latino-americana de enfermagem. 2008;16:218–23.

De Buyser SL, Petrovic M, Taes YE, Vetrano DL, Onder G. A multicomponent approach to identify predictors of hospital outcomes in older in-patients: a multicentre, Observational Study. PloS One. 2014;9(12):e115413.

De Buyser SL, Petrovic M, Taes YE, Vetrano DL, Corsonello A, Volpato S, Onder G. Functional changes during hospital stay in older patients admitted to an acute care Ward: a multicenter observational study. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96398.

Chester R, Jerosch-Herold C, Lewis J, Shepstone L. Psychological factors are associated with the outcome of physiotherapy for people with shoulder pain: a multicentre longitudinal cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(4):269–75.

Karstens S, Hermann K, Froböse I, Weiler SW. Predictors for half-year outcome of impairment in daily life for back pain patients referred for physiotherapy: a prospective observational study. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61587.

Kumar S, Bogle R, Banerjee D. Why do young people with chronic kidney disease die early? World J Nephrol. 2014;3(4):143–55.

Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Sarnak MJ. Clinical epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32(5 Suppl 3):S112–9.

Maguire PA, Taylor IC, Stout RW. Elderly patients in acute medical wards: factors predicting length of stay in hospital. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;292(6530):1251–3.

Warburton RN, Parke B, Church W, McCusker J. Identification of seniors at risk: process evaluation of a screening and referral program for patients aged > or =75 in a community hospital emergency department. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv. 2004;17(6):339–48.

Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the BARTHEL index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–5.

Heuschmann PU, Kolominsky-Rabas PL, Nolte CH, Hunermund G, Ruf HU, Laumeier I, Meyrer R, Alberti T, Rahmann A, Kurth T, et al. The reliability of the german version of the barthel-index and the development of a postal and telephone version for the application on stroke patients. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2005;73(2):74–82.

Schulc E, Pallauf M, Mueller G, Wildbahner T, Them C. Is the Barthel index an adequate assessment tool for identifying a risk group in elderly people living at home? Int J Nurs Clin Pract. 2015;2;140.

Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed "up & go": a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(2):142–8.

Tinetti ME. Performance-oriented assessment of mobility problems in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34(2):119–26.

Lysack CL. Chapter 23 - Household and Neighborhood Safety, Mobility. In: Lichtenberg PA, editor. Handbook of Assessment in Clinical Gerontology. 2nd ed. San Diego: Academic Press; 2010. p. 619–46.

Zemke J. Assessment Tinetti-test (performance oriented mobility assessment – POMA). GGP. 2018;02(01):13–5.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98.

Shulman KI, Shedletsky R, Silver IL. The challenge of time: clock-drawing and cognitive function in the elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1986;1(2):135–40.

Kessler J, Markowitsch H, Denzler P. Mini-mental-status-test (MMST). Göttingen: Beltz Test GmbH 2000.

Shulman KI, Pushkar Gold D, Cohen CA, Zucchero CA. Clock-drawing and dementia in the community: a longitudinal study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1993;8(6):487–96.

Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric depression scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clinical Gerontologist: The Journal of Aging and Mental Health; 1986.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang A-G. Statistical power analyses using G*power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41(4):1149–60.

Nobili A, Licata G, Salerno F, Pasina L, Tettamanti M, Franchi C, De Vittorio L, Marengoni A, Corrao S, Iorio A, et al. Polypharmacy, length of hospital stay, and in-hospital mortality among elderly patients in internal medicine wards. The REPOSI study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67(5):507–19.

Beauchet O, Fung S, Launay CP, Cooper-Brown LA, Afilalo J, Herbert P, Afilalo M, Chabot J. Screening for older inpatients at risk for long length of stay: which clinical tool to use? BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):156.

Saravay SM, Kaplowitz M, Kurek J, Zeman D, Pollack S, Novik S, Knowlton S, Brendel M, Hoffman L. How do delirium and dementia increase length of stay of elderly general medical inpatients? Psychosomatics. 2004;45(3):235–42.

Seematter-Bagnoud L, Martin E, Büla CJ. Health services utilization associated with cognitive impairment and dementia in older patients undergoing post-acute rehabilitation. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(8):692–7.

Binder EF, Robins LN. Cognitive impairment and length of hospital stay in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38(7):759–66.

Fogg C, Griffiths P, Meredith P, Bridges J. Hospital outcomes of older people with cognitive impairment: an integrative review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(9):1177–97.

Jansen L, van Schijndel M, van Waarde J, van Busschbach J. Health-economic outcomes in hospital patients with medical-psychiatric comorbidity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0194029.

Greaves J, Goodall D, Berry A, Shrestha S, Richardson A, Pearson P. Nursing workloads and activity in critical care: a review of the evidence. Intensive and Critical Care Nurs. 2018;48:10–20.

Hall LM, Doran D, Pink GH. Nurse staffing models, nursing hours, and patient safety outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2004;34(1):41–5.

Leemrijse CJ, de Boer ME, van den Ende CHM, Ribbe MW, Dekker J. Factors associated with physiotherapy provision in a population of elderly nursing home residents; a cross sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2007;7:7–7.

Klompstra L, Jaarsma T, Strömberg A. Physical activity in patients with heart failure: barriers and motivations with special focus on sex differences. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:1603–10.

Palmer K, Onder G. Comprehensive geriatric assessment: benefits and limitations. Eur J Int Med. 2018;54:e8–9.

Pilotto A, Cella A, Pilotto A, Daragjati J, Veronese N, Musacchio C, Mello AM, Logroscino G, Padovani A, Prete C, et al. Three Decades of Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment: Evidence Coming From Different Healthcare Settings and Specific Clinical Conditions. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(2):192.e191.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mrs. Nickel-Gögel for her contribution to CGA. We also thank the nursing staff of the Department of Cardiology and Angiology, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, and Department of Nephrology for conducting ISAR screenings upon hospital admission. We thank Mrs. Lucie Winkler for language editing the paper.

Funding

The authors receive no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. ACS Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing-original draft. JG Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing-original draft. CD Conceptualization Software, Project administration, Writing-review & editing. JS Data curation, Writing-review & editing. AK Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing-review & editing. GG Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing-review & editing. HF Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing-review & editing. RD Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing-review & editing. DMH Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing-original draft

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University Duisburg-Essen, need for consent was waived and the study was performed in accordance to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Since there are no details on individuals reported within the manuscript consent for publication was waived.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Supplement S1. Sample size calculation. Supplement S2. Characteristics of the total cohort also split by low vs high medical needs.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Scharf, AC., Gronewold, J., Dahlmann, C. et al. Clinical and functional patient characteristics predict medical needs in older patients at risk of functional decline. BMC Geriatr 20, 75 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-1443-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-1443-1