Abstract

Background

One of the crucial challenges for the future of therapeutic approaches to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is to target the main pathological processes responsible for disability and dependency. However, a progressive cognitive impairment occurring after the age of 70, the main population affected by dementia, is often related to mixed lesions of neurodegenerative and vascular origins. Whereas young patients are mostly affected by pure lesions, ageing favours the occurrence of co-lesions of AD, cerebrovascular disease (CVD) and Lewy body dementia (LBD). Most of clinical studies report on functional and clinical disabilities in patients with presumed pure pathologies. But, the weight of co-morbid processes involved in the transition from an independent functional status to disability in the elderly with co-lesions still remains to be elucidated. Neuropathological examination often performed at late stages cannot answer this question at mild or moderate stages of cognitive disorders. Brain MRI, Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) with DaTscan®, amyloid Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and CerebroSpinal Fluid (CSF) AD biomarkers routinely help in performing the diagnosis of underlying lesions. The combination of these measures seems to be of incremental value for the diagnosis of mixed profiles of AD, CVD and LBD. The aim is to determine the clinical, neuropsychological, neuroradiological and biological features the most predictive of cognitive, behavioral and functional impairment at 2 years in patients with co-existing lesions.

Methods

A multicentre and prospective cohort study with clinical, neuro-imaging and biological markers assessment will recruit 214 patients over 70 years old with a cognitive disorder of AD, cerebrovascular and Lewy body type or with coexisting lesions of two or three of these pathologies and fulfilling the diagnostic criteria for dementia at a mild to moderate stage. Patients will be followed every 6 months (clinical, neuropsychological and imaging examination and collection of cognitive, behavioural and functional impairment) for 24 months.

Discussion

This study aims at identifying the best combination of markers (clinical, neuropsychological, MRI, SPECT-DaTscan®, PET and CSF) to predict disability progression in elderly patients presenting coexisting patterns.

Trial registration

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

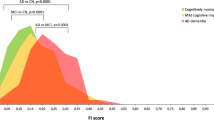

Whereas young patients presenting a neurocognitive disorder are mostly affected by pure lesions related to Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), Vascular Dementia (VaD) that may be induced by CerebroVascular Disease (CVD) or Lewy Body Dementia (LBD), ageing favours the occurrence of co-lesions of these pathologies (Fig. 1). Age is the strongest risk factor for dementia [1]. As the populations of Western countries age, the incidence and prevalence of dementia will rise significantly. The exponential relationship between age and the prevalence of dementia, combined with the increasing number of people surviving into old age, is driving the prevalence of AD and related diseases upward, particularly LBD and CVD.

AD, the most frequent neurodegenerative aetiology of neurocognitive disorders, is marked pathologically by plaques composed of ß amyloid deposits (Aß) surrounded by dystrophic neuritis, neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated tau, with activated microglia and reactive astrocytes, neuronal and synaptic loss. These lesions lead to neural loss and brain atrophy [2]. Amnestic presentation including impairment of learning and recall of recently learned information is the most common syndromic presentation of AD at the mild cognitive stage [3], latterly combined with aphasia, agnosia, apraxia and executive function impairment, some functional decline and behavioural disorders at the dementia stage [4].

LBD is marked by fluctuating cognitive decline, sleep neuropsychiatric disorders, early well-formed hallucinations, parkinsonism, and other supportive features such as dysautonomy and high sensitivity to antipsychotics [5].

CVD is the second or third most common cause of neurocognitive disorder, often associated to other pathological processes contributing to cognitive decline. Clinical symptoms depend on the location of the vascular lesions. Different CVD must be considered, i.e. multi-infarct dementia, post-stroke dementia and subcortical ischemic vascular disease [6]. Combined to clinical signs and symptoms, brain MRI is the imaging method of choice for in vivo assessment of CVD [7].

Numerous studies describe the clinical features and course of “pure” AD, in particular, the relationship between the cognitive status, behavioural disorder and the functional decline. Patients with the greatest decrease in cognitive function with respective average annual rates of decline in the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) show the highest decrease in score for the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) scale as well as the most severe behavioural disturbance [8]. Far fewer data are available for VaD and AD+CVD, despite their high prevalence [9]. Patients with VaD, AD+CVD, and AD present different features at baseline and during follow-up, what underlines the need to be distinguished between them. Few studies have followed CVD or AD+CVD patients longitudinally to assess the course of their cognitive decline. Such studies have also produced conflicting results [10,11,12]. With regard to AD and LBD, the study of Schneider et al. had shown that a large majority of the older persons with LBD and dementia had coexisting AD pathology [13] and according to Nelson et al., the clinical diagnoses of LBD and LBD + AD were suboptimal when contrasted with autopsy results [14], which makes the assessment of cognitive status, behavioural disorder and functional decline in these underlying lesions difficult.

The aim of this study is to identify the markers, as assessed by Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT-DaTscan®), Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and CerebroSpinal Fluid (CSF), combined with clinical information, that are the most predictive of functional disability progression in the elderly presenting a progressive cognitive decline related to AD, LBD, CVD and all mixed patterns. This approach will allow better defining the therapeutic targets in the elderly at a medium term.

Methods and design

Study aims

Principal objective

To identify imaging markers illustrating co-lesions of Alzheimer’s, cerebrovascular and Lewy body types of dementia the most predictive of functional disability progression.

Secondary objectives

-

1.

To identify a combination of clinical and blood markers, in addition to imaging markers, the most predictive of functional disability progression,

-

2.

To identify, in a subgroup, a combination of CSF markers, in addition to clinical/blood and imaging markers, the most predictive of functional disability progression,

-

3.

To identify clinical/blood, imaging and CSF markers the most predictive of the cognitive decline and neuropsychiatric symptoms,

-

4.

To evaluate the relationship between imaging and CSF markers related to co-lesions (AD, CVD and LBD) and neuropsychological performance,

-

5.

To identify, in AD, AD+CVD and LBD patients, the links between neuro-imaging, biological and clinical markers on the one hand, and the response to AD specific treatments on the other hand.

-

6.

To evaluate the relationship between amyloid deposition and co-lesions on the one hand, and the relationship between amyloid PET imaging markers and cognitive performances on the other.

Study design

Multicentre and prospective cohort study with 214 patients enrolled with pathology of AD, CVD or LBD or with clinical, neuroimaging and biological markers suggesting coexisting lesions of these three pathologies and fulfilling the diagnostic criteria for dementia at a mild to moderate stage.

Setting

The study is being conducted in 8 centres: 7 French national memory centres (Paris (AP-HP), Poitiers, Tours, Strasbourg, Grenoble, and 2 in Lyon) and 1 in the Monaco Principality.

Characteristics of participants

Inclusion criteria

-

Male or female subjects aged over 70 years

-

Out-patient consulting at one of the Memory Centres participating in the study

-

Patients meeting diagnosis criteria for dementia due to Alzheimer (McKhann, Knopman et al. 2011), cerebrovascular (NINCDS–AIREN criteria, Roma’n, G. C., Tatemichi, T. K., Erkinjuntti, T., et al. (1993), or Lewy body type (McKeith, Dickson et al. 2005), and patients presenting mixed signs and symptoms suggesting a combination of these diagnoses

-

Mild or moderate dementia stage (MMSE criteria > 15)

-

Being covered by health insurance

-

Patients with sufficient visual, auditory and oral and written French language skills to complete the clinical and neuropsychological evaluations

-

Accompanied by a close relation in sufficient contact with the subject to assess their dependency

Non-inclusion criteria

-

Patients with psychiatric disorders (Axe 1 DSMIV disease) excepting patients with depressive or anxious disorders stabilized for more than 3 months

-

Patients taking any neuroleptic psychotropic medication

-

Patients taking other psychotropic medication, with the exception of any antidepressant, hypnotic, anxiolytic, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors or memantine which has been prescribed and stabilised for more than 3 months

-

Patients with signs and symptoms suggestive of dementia related to diseases other than AD, CVD and LBD or mixed forms

-

Patients with other neurological diseases

-

Patients with progressive and unstable pathologies which could interfere with the variables under consideration

-

Deafness or blindness which could compromise evaluation of the patient

-

Patients being not able to undergo DaTscan®: with moderate or severe hepatic or renal impairment, a known hypersensitivity to ioflupane or any of the excipients

-

If amyloid PET accepted: Patients not being able to undergo Florbetapir: with moderate or severe hepatic or renal impairment, a known hypersensitivity

-

Patients living in an institution

-

Patients meeting brain MRI exclusion criteria (pacemakers, aneurysm clips, artificial heart valves, ear implants, metal fragments or foreign objects in the eyes, skin, or body) or refusing MRI

-

Patients being under guardianship

Measures

All measures are reported in Table 1.

Timeline

Start of recruitment: January 2014.

Duration of the recruitment period: 4.5 years.

Duration of individual participation: 2 years.

Final data collection date for primary outcome measure: July 2018.

End of the study: October 2020.

Outcome measures

The primary endpoint is based on the dependency progression at 2 years defined by the Disability Assessment for Dementia (DAD) scale.

Neuropsychological tests: Performances assessments

This assessment is included in the usual clinical practice. These tests will take place in the presence of a neuropsychologist. Besides the clinical evaluation and the initial neuropsychological inventory adapted to each team’s habits to obtain a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) value, all subjects will also undergo:

-

➢ For the diagnosis and correlation with imaging and CSF markers: MMSE [15] for global cognition, 16-item Free and Cued Recall Test (FCRT) to evaluate verbal episodic memory [16], Grober and Buschke [17] to evaluate visual recognition memory, Delayed Matching-to-Sample (DMS 48) [18] to evaluate visual recognition memory, DO80 [19] and Bachy-Langedock denomination task (Bachy-Langedock 1989) to evaluate language, Verbal fluency (letter P and category: animal in 2 min) [20], Working memory and executive functions with Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale span digit test (Wechsler 1981), Trail Making test [21] and Stroop Test [22] to evaluate executive function, Visual Object and Space, Visuospatial, and visuo-perceptive abilities were studied, Perception battery [23], and Praxes and meaningless gestures comprehension test [24].

-

➢ For longitudinal assessments: MMSE, BREF [25] and Adas-Cog [26] to assess quantification of cognitive function.

MRI: Parameters studied and sequences

This acquisition is included in the clinical usual practice and will be performed on 3 T MRI in all centres.

A morphologic MRI will be performed as part of the battery of exploratory tests habitually carried out when a patient presents with degenerative cognitive disorders on diagnosis.

Parameters studied will be brain volume, ventricular volume, regional cortical volume, hippocampal volume, ischemic vascular lesions and microbleeds.

These analyses will perform on:

-

1 mm isotropic 3D T1 sequences without contrast injection for the quantification of Brain Parenchymal Fraction and Ventricles

-

T2 gradient echo sequence, for the detection of microbleeds and amyloid angiopathy

-

1 mm isotropic 3D FLAIR sequence (only for 3 T) or 3 mm axial 2DFLAIR (1.5 T), for the quantification of vascular and bright objects

-

Diffusion (b = 1000) with ADC cartography, for silent infarcts

Processing of MRI data will be performed by the “Centre d’Acquisition et de Traitement Automatisé des Images” (CATI, Head: Jean-François Mangin, Orsay). Quality control at the different steps of MRI data acquisition will be made.

SPECT: DaTscan® product and acquisition

Image acquisition and reconstruction will be performed with a SPECT/CT device, equipped with low-energy high-resolution (LEHR) parallel arrays, 3 h after intravenous injection of 111 to 185 MBq of 123I-FP-CIT and after oral administration of 400 mg of potassium perchlorate for thyroid uptake freezing. This exam will be conducted under the same conditions as the usual clinical practice. DaTscan (123I-Ioflupane Injection) is a radiopharmaceutical indicated for striatal dopamine transporter visualization using SPECT.

The acquisition parameters are standardized and will last 30 min. Quality control and processing of SPECT data will be performed by the CATI.

Amyloid PET: Product and acquisition

The acquisition of the PET image will start about from 30 to 50 min after intravenous injection of Florbetapir and will last 10 min. Patients must be lying on the back, head positioned so that the brain, including the cerebellum, are at centre of the field of view of the camera. It will be necessary to limit the movements of the head using adhesive strips or any flexible contention to maintain the head. The reconstruction should include a correction in order to obtain a size of pixels between 2.0 and 3.0 mm for axial images.

Florbetapir is a tracer indicated for PET imaging to estimate the density of beta amyloid plaques in the brain of adult patients with cognitive decline who are under evaluation for AD and other causes of cognitive impairment.

All data will be analysed by the CERMEP which is an in vivo multimodal dedicated to basic research and clinical imaging centre, in Lyon.

LP: Biomarkers

All collected samples will be sent to a central biobank for storage (Neurobiotec bank). Any use of the blood biobank will need to be approved by the study co-coordinators and the scientific committee.

The LP will follow the guidelines published in 2011 [27].

The CSF biomarkers will be determined in duplicates using standardized, commercially available ELISA Kits (Innotest β-amyloid 1–42, Tau, and Phospho-Tau (181P), Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium). The samples will be analysed with the same batch of assay kits to decrease variability inter-lots of production of ELISA kits.

The biomarkers t-Tau, p-Tau, Aβ1–42, Aβ1–40, Total tau (t-tau),181 Phosphorylated tau (p-tau) and a-syn will be measured. If needed and depending upon the data obtained with these 3 first biomarkers, Aβ1–40 will be also measured.

Data collection procedures

The anonymity of patients will ensure the following will be reported on the Case Report Form (CRF): the first letter of the name and surname, the number of patient inclusion corresponding to order number and the number of centre.

For each patient included in the study, case report forms anonymized includes the following informations: information to help guide the data collection, inclusion and non-inclusion Criteria to validate, patient Characteristics, clinical data, neuropsychological tests, blood sampling, MRI results, SPECT-DaTscan® results, Amyloid PET results, LP results, serious Adverse Events and withdrawal from study.

Each of these informations will exist in duplicate. Investigators will retain the duplicate, and will give the original to the Clinical Research Associate (CRA) monitor. CRF will be kept in the patient’s medical records by the investigator during the study. For each patient, the CRA will centralize slips and links and archive them. The number of inclusion will be present on each sheet of the CRF. This number of inclusion will be used to connect the various slips of the same patient. At each inclusion or withdrawal from study, the medical investigator will notify the Coordination Centre of the study by fax.

Sample size

The Required number of subjects is estimated on the primary endpoint: disability progression at 2 years. From the following hypothesis:

-

Frequency of disability progression at 2 years = 40%

-

Relative risk of rapid disability progression at 2 years related to global atrophy = 1.6

-

Alpha risk (α) = 5%

-

Statistical power (1- β) = 90%

-

Two-tailed test

The Required number of subjects is 178. With an expected drop-out rate of 20%, the number of subjects to be included is estimated at 214 patients.

Statistic analysis

Statistical analyses will be under the responsibility of Lyon CM2R (Research and Resources Centre Memory).

Population descriptive analysis

Descriptive analysis of data collected from patients will be conducted. Quantitative variables will be described according to their size, mean, standard deviation, median, quartiles, and range of values. Qualitative variables will be described by numbers and percentages.

Principal objective: Analysis of predictive markers

An analysis of predictors of occurrence of loss of autonomy at 2 years will be conducted on patients with dementia, by providing for qualitative factors, the distribution of patients with loss of autonomy and quantitative factors, means ± standard deviation. The predictive markers will be the clinical, radiological and biological measures.

Correlations analysis will be used to compare the Pearson correlation coefficient between the DAD and markers.

Analysis of variance and covariance will be used to compare means of continuous variables, including baseline scores and changes in scores over time. In multivariate analysis based on a mixed regression model will then estimate the change in score slope of the Inclusion to 2 years and the adjusted effects of predictive markers (imaging and biomarkers).

Secondary objectives

The following analyses will be used to assess secondary objectives: Correlations by Pearson’s correlation coefficient, Multivariate analysis: mixed regression model, Wilcoxon signed rank test, Logistic regression models and Percentages per group will be compared by Pearson’s Chi2 test (if the numbers are expected greater than or equal to 5), otherwise by Fisher’s exact test.

Statistical significance level

Test results will be defined as statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Discussion

The CLEM study aims at better understanding the factors underlying functional disability progression, cognitive decline and behavioural disorders in coexisting AD, CVD and LBD at mild or moderate dementia stages. Its main objective is to identify imaging markers illustrating co-lesions, the most predictive of functional disability progression.

Different combinations of biomarkers may be used in a differential diagnosis of neurodegenerative/vascular diseases depending on the degree of clinical relevance. First, imaging, primarily MRI, is used to eliminate a non-degenerative cause, including the different types of CVD. In this way, the International Society for Vascular Behavioral and Cognitive Disorders (VASCOG) proposed criteria for vascular cognitive disorders, in line with the DSM-5, to take into consideration the developments in other cognitive disorders such as AD [28]. Then, in order to objectify the distribution of atrophy suggestive of specific neurodegenerative disease, MRI will remain an essential tool. Thus, to distinguish AD and LBD, medial temporal lobe atrophy is mainly associated with AD diagnosis, with a good discriminatory power with LBD in pathologically confirmed cases [29]. For similar levels of dementia severity, LBD appears to have greater involvement of subcortical brain atrophy than AD [30]. Hippocampal atrophy can also be observed in VaD [31] and in frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) [32]. However, Laakso et al. found that hippocampal atrophy is significantly greater in VaD patients than in control subjects but less than in AD patients [33]. And, differently from AD, in FTLD, atrophy in the temporal lobes preferentially involves the anterior part of medial temporal lobe and the amygdala more than the hippocampus [34]. Moreover, there was evidence of a difference in trends of atrophy in the cingulate (more anterior in FTLD and more posterior in AD) [32]. Diffusion tensor MRI can also be helpful in differentiating FTLD from AD with greater damage especially in frontal white matter in FTLD [35]. However, white matter hyperintensities has been reported as similar in AD and LBD [36] while a greater number of microbleeds (MBs) was reported in LBD than in AD [37].

In addition to these brain MRI biomarkers, SPECT and PET are also of interest in the differential diagnosis between LBD and other aetiologies of dementia [38, 39]. For-example, SPECT-DatSCAN showed that presynaptic dopaminergic neurotransmission (Dopamine transporter, DAT) in substantia nigra and striatum is typically deficient in LBD whereas no deficit was observed in AD [40]. Moreover, approximately 50% of people with LBD also have amyloid accumulation visualized using amyloid PET, in a very similar distribution to that seen in AD, but to a lesser extent and with amyloid plaques more often diffuse rather than neuritic [41, 42]. Other brain imaging markers, such as 99mTc-HMPAO SPECT and FDG-PET modality also support corroborative signs of focal atrophy and can aid the differentiation of AD, FTLD, VaD, and LBD [43].

Since alterations in the CSF have been detected up to decades before the appearance of clinical symptoms in particular settings [44], the value of CSF analysis is also relevant in the differential diagnosis. In this way, CSF amyloid and tau biomarkers can for-example distinguish AD from VaD with a specificity of 80% [45], but CSF amyloid is not helpful in distinguishing between AD and LBD [46].

With increasing age biomarkers are less efficient for differential diagnosis of neurodegenerative disease, probably due to co-existing lesions. The etiological diagnosis is difficult when patients disclose symptoms suggestive of various diseases. Although many reviews have addressed diagnostic and therapeutic issues in pure AD, CVD and LBD, very few have focused on coexisting lesions. For example, LBD and AD are distinct disorders but they often coexist. Indeed, in LBD patients, the density of senile plaques may be similar to that observed in AD [47] and these cases are often regarded as ‘mixed’ cases of LBD with associated AD (LBD/AD). Armstrong et al. showed that the Abeta pathology of LBD/AD cases is different to that observed in patients with AD alone [48].

Regarding AD and CVD, some evidence from amyloid PET imaging suggests that increased vascular risk [49, 50] such as hypertension, diabetes, and smoking and CVD [51, 52] such as stroke, lacunar infarcts, CAA, microbleeds, and WM changes may accelerate amyloid production/aggregation/deposition and thus contribute to the pathology and symptomatology of AD [53]. One of the mechanisms linking CVD to AD is decreased cerebral blood flow, which modulates amyloid precursor protein cleavage enzymes leading to increased amyloid production [54]. Additionally, the association of the APOE4 genotype with an increased risk for both AD and CVD further suggests a potential link between CVD, and AD [55]. At the same level of cognitive impairment, AD patients with concomitant CVD were reported to be older and more severely demented, but have less severe AD pathology than patients without CVD [56]. A combination of AD and CVD is usually registered as a close third, moving up to first or second in rank in community-based studies of the oldest of old.

Since then, it seems important to establish consensus about diagnosis criteria for underlying lesions that contribute differently in the progression of cognitive, behavioural and functional impairment compared to pure pathology. Most of the studies report on functional, behavioural, and clinical abnormalities in patients with pure pathologies. For example, in AD subjects, autonomy loss correlates with frontal, temporal, and occipital structure atrophy [57]. In the LBD group, increased rates of cortical thinning in the frontal and parietal regions are significantly correlated with motor deterioration [58]. Other studies comparing functional ability between pure pathologies showed that VaD may be associated with a faster decline in physical functionality compared to AD [59]. Another study of 84 patients showed that LBD patients were more functionally impaired and had more motor and neuropsychiatric difficulties than patients with AD with similar cognitive scores [60].

But less is known regarding coexisting lesions in the assessment of the progression of cognitive, behavioural, and functional impairment. Yet, according to different studies, AD/LBD combination tends to induce greater cognitive and behavioural impairment than pure LBD [61, 62]. A progressive cognitive impairment occurring after the age of 70 is often related to mixed lesions of neurodegenerative and vascular origins. This complicates one of the crucial challenges for the future of therapeutic approaches in the elderly which is to target the main pathological process responsible for disability. Indeed, Schäufele et al. showed that, by controlling the degree of severity of dementia variables, only age and disability contributed to the prediction of mortality in patients with Alzheimer type, vascular or mixed dementia [63]. The longitudinal design using imaging, biological, and clinical biomarkers may give insight into helping to predict the precise role and weight of each brain lesion type in the disability progression in the co-existing pathologies and to develop preventive strategies to reduce the burden of disability related to these co-lesions.

Limitations and strengths

The CLEM study may have some limitations. Firstly, recruitment may be difficult. Given the age of the patients, this is a dense protocol including several imaging techniques and clinical and biological assessments even if some are optional. Ideally, this study would have necessitated to follow-up the subjects for a long time but longitudinal studies of LBD for example are difficult owing to the higher mortality rates compared to AD [64].

Also, neuropathological correlates may be lacking, since discrepancies between pathological findings and clinical, as well as neuroimaging data are well known. Patient autopsy would be interesting to establish convergence evidence from imaging and biological diagnosis.

The present study also has strengths. Literature often assesses pure pathology but considers coexisting pathology only at the time of death. Moreover, to our knowledge, CLEM is the first study to follow during 2 years the disability of patients with presumed co-lesions as assessed with clinical, radiological and biological markers.

Perspectives

It is crucial to better understand the predictors of the responses to current or future specific treatments in elderly patients affected by neurocognitive disorders. Since efficiency of disease modifying drugs has not been disclosed yet, and since side effects must be carefully considered, we aim to better define the population who would benefit from specific symptomatic or disease modifying drugs. These drugs will increasingly have to target the actual pathological processes responsible for functional decline in the medium term.

This program will allow further research on a larger cohort, in particular to validate a predictive score of functional disability risk in elderly presenting with progressive cognitive decline. A brain donor program will be developed and based on this cohort to further study the intimated neuropathological processes associated to dementia in the elderly at the terminal stage. This will also help in adapting non-drug therapeutic approaches and co-morbidity care, as well as the prevention of impairment of quality of life for the patients and their caregivers, risk of institutionalization, and costs of care.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADAS-cog:

-

Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale

- ADL:

-

Activities of Daily Living

- ANSM:

-

Agence Nationale de Sécurité des Médicaments French Agency for the Safety of Health Products

- ARWM:

-

Age-Related White Matter Changes

- BREF :

-

Batterie Rapide d’Efficience Frontale

- CAA:

-

Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy

- CDR:

-

Clinical Dementia Rating scale

- CHU:

-

Centre Hospitalier Universitaire

- CMRR:

-

Centre de Mémoire, de Ressources et de Recherche

- CPP:

-

Comité de Protection de Personnes (French Committee)

- CRA:

-

Clinical Research Associate

- CRF:

-

Case Report Form

- CSF:

-

Cerebro-Spinal fluid

- CVD:

-

CerebroVascular Disease

- DAD:

-

Disability Assessment for Dementia

- DMS:

-

Delayed Matched to Sample

- DO:

-

Denomination Objet

- EDF:

-

Echelle de Dysfonctionnement frontal

- FCRT:

-

Free and Cued Recall Test

- FLAIR:

-

Fluid Attenuated Inversion Recovery

- IADL:

-

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

- LBD:

-

Lewy Body Dementia

- LBD:

-

Lewy Body Dementia

- LP:

-

Lumbar Puncture

- MBs:

-

Microbleeds

- MCI:

-

Mild Cognitive Impairment

- MMSE:

-

Mini-Mental State Examination

- MRI:

-

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- MTA:

-

Medial Temporal Atrophy

- NPI:

-

NeuroPsychiatric Inventory

- PET:

-

Positron Emission Tomography

- RL/RI 16:

-

Rappel Libre/Rappel Indicé 16 mots

- SAE:

-

Side Adverse Event

- SPECT:

-

Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography

- TMT:

-

Trail Making Test

- VaD:

-

Vascular Dementia

- VBM:

-

Voxel Basel Morphometry

References

McDowell I. Alzheimer’s disease: insights from epidemiology. Aging Milan Italy. 2001;13:143–62.

Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–6.

Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2011;7:270–9.

McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2011;7:263–9.

McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O’Brien JT, Feldman H, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB consortium. Neurology. 2005;65:1863–72.

O’Brien JT, Erkinjuntti T, Reisberg B, Roman G, Sawada T, Pantoni L, et al. Vascular cognitive impairment. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:89–98.

Pohjasvaara T, Mäntylä R, Ylikoski R, Kaste M, Erkinjuntti T. Comparison of different clinical criteria (DSM-III, ADDTC, ICD-10, NINDS-AIREN, DSM-IV) for the diagnosis of vascular dementia. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke-Association Internationale pour la Recherche et l’Enseignement en neurosciences. Stroke J Cereb Circ. 2000;31:2952–7.

Lechowski L, De Stampa M, Tortrat D, Teillet L, Benoit M, Robert PH, et al. Predictive factors of rate of loss of autonomy in Alzheimer’s disease patients. A prospective study of the REAL.FR cohort. J Nutr Health Aging. 2005;9:100–4.

Bruandet A, Richard F, Bombois S, Maurage CA, Deramecourt V, Lebert F, et al. Alzheimer disease with cerebrovascular disease and vascular dementia: clinical features and course compared with Alzheimer disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:133–9.

Aharon-Peretz J, Daskovski E, Mashiach T, Kliot D, Tomer R. Progression of dementia associated with lacunar infarctions. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2003;16:71–7.

Nyenhuis DL, Gorelick PB, Freels S, Garron DC. Cognitive and functional decline in African Americans with VaD, AD, and stroke without dementia. Neurology. 2002;58:56–61.

Agüero-Torres H, Fratiglioni L, Winblad B. Natural history of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: review of the literature in the light of the findings from the Kungsholmen project. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;13:755–66.

Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007;69:2197–204.

Nelson PT, Jicha GA, Kryscio RJ, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, Cooper G, et al. Low sensitivity in clinical diagnoses of dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurol. 2010;257:359–66.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98.

Van der Linden M, Coyette F, Poitrenaud J, Kalafat M, Calicis F, Wyns C, et al. L’épreuve de rappel libre/rappel indicé à 16 items (RL/RI-16) [Internet]. Solal; 2004 [cited 2016 Nov 29]. Available from: http://orbi.ulg.ac.be/handle/2268/26018

Grober E, Buschke H, Crystal H, Bang S, Dresner R. Screening for dementia by memory testing. Neurology. 1988;38:900–3.

Barbeau E, Ceccaldi M. L’évaluation des troubles de la mémoire au stade prédémentiel de la maladie d’Alzheimer: le DMS48. Neurologiecom. 2010;2:152–4.

Snodgrass JG, Vanderwart M. A standardized set of 260 pictures: norms for name agreement, image agreement, familiarity, and visual complexity. J Exp Psychol [Hum Learn]. 1980;6:174–215.

Cardebat D, Doyon B, Puel M, Goulet P, Joanette Y. Formal and semantic lexical evocation in normal subjects. Performance and dynamics of production as a function of sex, age and educational level. Acta Neurol Belg. 1990;90:207–17.

Reitan RM. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills. 1958;8:271–6.

Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J Exp Psychol. 1935;18:643–62.

Rapport LJ, Millis SR, Bonello PJ. Validation of the Warrington theory of visual processing and the visual object and space perception battery. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1998;20:211–20.

Mahieux-Laurent F, Fabre C, Galbrun E, Dubrulle A, Moroni C, groupe de réflexion sur les praxies du CMRR Ile-de-France Sud. Validation of a brief screening scale evaluating praxic abilities for use in memory clinics. Evaluation in 419 controls, 127 mild cognitive impairment and 320 demented patients. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2009;165:560–7.

Dubois B, Slachevsky A, Litvan I, Pillon B. The FAB: a frontal assessment battery at bedside. Neurology. 2000;55:1621–6.

Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL. A new rating scale for Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141:1356–64.

Perret-Liaudet A, Pelpel M, Tholance Y, Dumont B, Vanderstichele H, Zorzi W, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid collection tubes: a critical issue for Alzheimer disease diagnosis. Clin Chem. 2012;58:787–9.

Sachdev P, Kalaria R, O’Brien J, Skoog I, Alladi S, Black SE, et al. Diagnostic criteria for vascular cognitive disorders: a VASCOG statement. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2014;28:206–18.

Burton EJ, Barber R, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB, Robson J, Perry RH, Jaros E, et al. Medial temporal lobe atrophy on MRI differentiates Alzheimer’s disease from dementia with Lewy bodies and vascular cognitive impairment: a prospective study with pathological verification of diagnosis. Brain J Neurol. 2009;132:195–203.

Watson R, Colloby SJ, Blamire AM, O’Brien JT. Subcortical volume changes in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease. A comparison with healthy aging. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28:529–36.

Scher AI, Xu Y, Korf ESC, Hartley SW, Witter MP, Scheltens P, et al. Hippocampal morphometry in population-based incident Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia: the HAAS. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:373–6.

Barnes J, Godbolt AK, Frost C, Boyes RG, Jones BF, Scahill RI, et al. Atrophy rates of the cingulate gyrus and hippocampus in AD and FTLD. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:20–8.

Laakso MP, Partanen K, Riekkinen P, Lehtovirta M, Helkala EL, Hallikainen M, et al. Hippocampal volumes in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease with and without dementia, and in vascular dementia: an MRI study. Neurology. 1996;46:678–81.

Du A-T, Schuff N, Kramer JH, Rosen HJ, Gorno-Tempini ML, Rankin K, et al. Different regional patterns of cortical thinning in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Brain J Neurol. 2007;130:1159–66.

Profiles of white matter tract pathology in frontotemporal dementia. - PubMed - NCBI [Internet]. [cited 2017 May 16].

Oppedal K, Aarsland D, Firbank MJ, Sonnesyn H, Tysnes OB, O’Brien JT, et al. White matter hyperintensities in mild lewy body dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord Extra. 2012;2:481–95.

Fukui T, Oowan Y, Yamazaki T, Kinno R. Prevalence and clinical implication of microbleeds in dementia with lewy bodies in comparison with microbleeds in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord Extra. 2013;3:148–60.

Debouverie O, Coudroy R, Merlet-Chicoine I, Salmon F, Gil R, Paccalin M. Accuracy of fluoropropyl-2beta-carbomethoxy-3beta-(4- iodophenyl) nortropane datscan for the diagnosis of lewy body dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:209–10.

Farid K, Volpe-Gillot L, Caillat-Vigneron N. Brain SPECT in Lewy body dementia. Presse Médicale Paris Fr. 2011;40:581–6.

Walker Z, Costa DC, Walker RWH, Shaw K, Gacinovic S, Stevens T, et al. Differentiation of dementia with Lewy bodies from Alzheimer’s disease using a dopaminergic presynaptic ligand. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:134–40.

Vercher-Conejero JL, Rubbert C, Kohan AA, Partovi S, O’Donnell JK. Amyloid PET/MRI in the differential diagnosis of dementia. Clin Nucl Med. 2014;39:e336–9.

Ballard C, Ziabreva I, Perry R, Larsen JP, O’Brien J, McKeith I, et al. Differences in neuropathologic characteristics across the Lewy body dementia spectrum. Neurology. 2006;67:1931–4.

Yeo JM, Lim X, Khan Z, Pal S. Systematic review of the diagnostic utility of SPECT imaging in dementia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;263:539–52.

Thordardottir S, Ståhlbom AK, Ferreira D, Almkvist O, Westman E, Zetterberg H, et al. Preclinical cerebrospinal fluid and volumetric magnetic resonance imaging biomarkers in Swedish familial Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis JAD. 2015;43:1393–402.

Kapaki E, Paraskevas GP, Zalonis I, Zournas C. CSF tau protein and beta-amyloid (1-42) in Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis: discrimination from normal ageing and other dementias in the Greek population. Eur J Neurol. 2003;10:119–28.

Gómez-Tortosa E, Gonzalo I, Fanjul S, Sainz MJ, Cantarero S, Cemillán C, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers in dementia with lewy bodies compared with Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1218–22.

Armstrong RA, Cairns NJ, Lantos PL. beta-Amyloid (A beta) deposition in the medial temporal lobe of patients with dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurosci Lett. 1997;227:193–6.

Armstrong RA, Cairns NJ, Lantos PL. Beta-amyloid deposition in the temporal lobe of patients with dementia with Lewy bodies: comparison with non-demented cases and Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2000;11:187–92.

Reed B, Villeneuve S, Mack W, DeCarli C, Chui HC, Jagust W. Associations between serum cholesterol levels and cerebral amyloidosis. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:195–200.

Kester MI, Goos JDC, Teunissen CE, Benedictus MR, Bouwman FH, Wattjes MP, et al. Associations between cerebral small-vessel disease and Alzheimer disease pathology as measured by cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:855–62.

Garcia-Alloza M, Gregory J, Kuchibhotla KV, Fine S, Wei Y, Ayata C, et al. Cerebrovascular lesions induce transient β-amyloid deposition. Brain J Neurol. 2011;134:3697–707.

Lee C-W, Shih Y-H, Kuo Y-M. Cerebrovascular pathology and amyloid plaque formation in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2014;11:4–10.

Honjo K, Black SE, Verhoeff NPLG. Alzheimer’s disease, cerebrovascular disease, and the β-amyloid cascade. Can J Neurol Sci J Can Sci Neurol. 2012;39:712–28.

Gupta A, Iadecola C. Impaired Aβ clearance: a potential link between atherosclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:115.

Casserly I, Topol E. Convergence of atherosclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease: inflammation, cholesterol, and misfolded proteins. Lancet Lond Engl. 2004;363:1139–46.

Jellinger KA. Small concomitant cerebrovascular lesions are not important for cognitive decline in severe Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:520–1.

Marshall GA, Olson LE, Frey MT, Maye J, Becker JA, Rentz DM, et al. Instrumental activities of daily living impairment is associated with increased amyloid burden. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2011;31:443–50.

Mak E, Su L, Williams GB, Watson R, Firbank MJ, Blamire AM, et al. Progressive cortical thinning and subcortical atrophy in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:1743–50.

Tolea MI, Morris JC, Galvin JE. Trajectory of mobility decline by type of dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2016;30:60–6.

McKeith IG, Rowan E, Askew K, Naidu A, Allan L, Barnett N, et al. More severe functional impairment in dementia with lewy bodies than Alzheimer disease is related to extrapyramidal motor dysfunction. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:582–8.

Olichney JM, Galasko D, Salmon DP, Hofstetter CR, Hansen LA, Katzman R, et al. Cognitive decline is faster in Lewy body variant than in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1998;51:351–7.

Kraybill ML, Larson EB, Tsuang DW, Teri L, McCormick WC, Bowen JD, et al. Cognitive differences in dementia patients with autopsy-verified AD, Lewy body pathology, or both. Neurology. 2005;64:2069–73.

Schäufele M, Bickel H, Weyerer S. Predictors of mortality among demented elderly in primary care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14:946–56.

Williams MM, Xiong C, Morris JC, Galvin JE. Survival and mortality differences between dementia with Lewy bodies vs Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67:1935–41.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Ouazna Tassa (for skillful assistance with subject recruitment and safety monitoring), Floriane Delphin (for conforming to neuropsychological assessment) and Thomas Liles (for conforming to correct scientific English) and the CLEM Group (for helping in the recruitment of patients).

The CLEM group: Zina Barrou, Emilie Beaufils, François Bertin-Hugault, Laure Brackers de Hugo, Marie-Hélène Coste, François Cotton, Keren Danaila, Lucile Dourthe, Sylvain Gaujard, Yves Guilhermet, Sandrine Greffard, Pierre Grosmaître, Solange Hesse, Caroline Hommet, Lucie Mora, Sandrine Louchart, Zaza Makaroff, Armand Perret-Liaudet, Kévin Polet, Isabelle Rouch, Catherine Sagot, Alain Sarciron, Aziza Sediq Waissi, Christian Scheiber, Ouazna Tassa, Jing Xie.

Funding

The CLEM study has been funded by the National French Program of Hospital Clinical Research (Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique National), 2012.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PKS and NB conceived the idea for the study and participated in design of the study. NB drafted the manuscript for submission to BMC Geriatrics and provided project management of the study. SR and EB assisted with subject recruitment and safety monitoring. RB revised the manuscript for intellectual content. DF, AP, MV, FB, MP,TD, PG and OM participate in subject recruitment. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent is obtained from subject and caregiver prior to the initiation of the study. The study is carried out in accordance with the French and European Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki (Edinburg 2000, Washington 2002, Tokyo 2005) and ICH (International Conference on Harmonisation) Recommendations and Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice.

In accordance with law n° 2004.806 and the ethical body governing biomedical research, the approval of the French ‘Comité de Protection des Personnes’ (CPP) has been submitted to ‘CPP Sud Est III’. CLEM study has been registered in the clinical trials (Current Controlled Trials NCT02052947).

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, a Wholly Owned Subsidiary of Eli Lilly & Company has contributed to the funding of 50 doses of Florbetapir for the PET examination.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Boublay, N., Fédérico, D., Pesce, A. et al. Study protocol on Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders: focus on clinical and imaging predictive markers in co-existing lesions. BMC Geriatr 18, 280 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0949-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0949-2