Abstract

Background

Esophageal fistula and stricture is rare but life-threatening complication for esophageal cancer. The management of esophageal fistula and stricture remains challenging. We aimed to determine the safety, feasibility and efficacy of covered metallic stent and three tubes placement for the management of esophageal fistula and stricture.

Methods

Between May 2012 and March 2018, all patients with esophageal fistula and stricture were treated using three tubes or covered metallic stent placement. Patients in group A received covered stents and three tubes placement. Patients in group B only received three tubes placement. Continue abscess drainage and nutritional support was performed after procedure. Three tubes or esophageal stents were removed once esophageal fistula heals. The related medical records were retrospectively assessed.

Results

Thirty-seven consecutive patients with esophageal fistula and stricture were enrolled, including 26 patients in group A and 11 patients in group B. Stent placement procedure was technically successful in 25 patients (96.2%). A total of 42 covered stents were inserted. Seventeen esophageal stents were successfully removed from 10 patients. The median retention duration was 3.3 months and 3.4 months for stent and abscess drainage tubes, respectively. One perioperative death due to massive hemorrhage was observed 21 days after stent placement. The abscess cavity was decreased or disappeared in 17 cases and 4 cases in group A and group B, respectively. During follow up, patients in group A still showed a significant better condition of normal diet than that in group B (p < 0.05). Fourteen patients died of cancer recurrence, 3 patients died of massive digestive bleeding and 2 patients died of severe pulmonary infection. The median survivals were 14.8 months and 13.2 months for group A and group B, respectively.

Conclusions

Covered metallic stent placement is safe, feasible and efficacious for treatment of esophageal fistula and stricture, with a better condition of normal diet than patients only received three tubes placement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

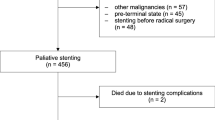

Esophageal fistula combined with esophageal stricture is a rare but life-threatening complication for patients with esophageal cancer or esophagogastric carcinoma [1, 2]. Contamination of abscess cavity may cause massive digestive bleeding or even death. Most of patients with esophageal carcinoma will receive only palliative treatment, considering that those patients often show advanced inoperable disease at the time of diagnosis.

Various conservative protocols have been reported for the management of esophageal fistula, including biodegradable fistulae plugs, transluminal drainage and esophageal stent placement [3,4,5,6]. Plain malignant esophageal strictures can be successfully treated and show a satisfactory result. However, in the presence of an esophageal fistula, palliation presents a challenge and has a poor prognosis [2, 4, 7]. There are few reports of studies on the treatment for esophageal stricture complicated with fistula [8]. In this study, three tubes and covered esophageal stent was used. We aimed to determine the safety, feasibility and efficacy of this method for the management of esophageal fistula and stricture.

Methods

Patient selection

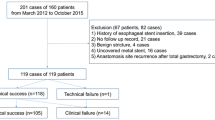

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee Board of First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University. Informed consent was obtained from each patient. Between May 2012 and March 2018, all patients with malignant esophageal fistula and stricture in our institution were enrolled and retrospectively analyzed. The diagnosis of an esophageal fistula and stricture was made according to the finding of chest computed tomography (Fig. 1) and esophagography (Fig. 2a). According to the treatment protocol, patients were divided into two groups. All patients were suitable for placement of covered stents and three tubes placement (group A), however, some patients were unable to receive stents placement because of economic pressure or reluctance to receive stent implantation and only received three tubes placement (group B). The three tubes are presumably a nasocavity drain placed fluoroscopically, a nasojejunal feeding tube and a nasogastric drainage tube, this should be stated clearly. After normal eating, the three tubes and stents were removed. Patients in group A whose fistula has disappeared by esophagogram can start normal diet 3–5 days after stent placement. Patients in group B are not advised to eat through mouth unless the fistula has disappeared, so as not to aggravate the infection.

Three tubes and covered stent placement. a Esophagography shows esophageal mediastinal fistula and esophageal stricture in the middle part of esophagus. b Abscess drainage tube was inserted. c An esophageal covered stent was placed to block the fistula. d Esophagography shows that the contrast agent flows though the stent with no fistula immediately after stent placement

Three tubes placement

All procedures were performed under fluoroscopic guidance. The esophagus was anesthetized by taking lidocaine gel. A 5-F catheter was introduced into the distal end of abscess cavity, followed by exchange with a 5-F pigtail catheter or 5-F straight catheter (Cook Medical, Inc., Bloomington, IN). The abscess cavity was rinsed with saline daily, and continuous negative pressure suction was performed to make sure effective drainage (Fig. 2b). A jejunal feeding tube was placed for infusing enteral nutrition solution. The gastrointestinal decompression tube was inserted to decrease reflux. Patients did not feed by mouth until complete block of fistula by covered stent or successful sealing was confirmed via esophagography.

Covered esophageal stent placement

The self-expandable metallic stents was covered by polytetrafluoroethylene membrane (Nanjing Micro-Tech Medical Company, Nanjing, China). The stent was made of nitinol alloy and the outside of the stent were covered. Stent diameter ranges from 14 to 22 mm (interval 2 mm) and stent length ranges from 60 to 160 mm (interval 20 mm). Recovery lines in the proximal end are used for the adjustment or recovery of the stent. The delivery system of stent is 8 mm in diameter and 650 mm in length.

A 5-F cobra catheter was inserted into the gastric cavity, followed by exchange with a stiff guide wire. Along the stiff guide wire, a covered stent system was delivered and released to block the esophageal fistula. A repeated esophagography was performed immediately after stent placement to confirm the closure of fistula (Fig. 2c-d). During follow up, chest computerized tomography (CT) and/or esophagography were performed to show the change of the abscess cavity. The three tubes were removed if abscess cavity disappear was confirmed by esophagography and chest CT (Fig. 3). The indications for stent removal include severe restenosis leading to dysphagia, obvious stent migration leading to failure of stent adjustment, healing of fistula and stenosis relief to return to normal diet.

Examinations after stent placement during follow up. a The chest CT scan shows decrease of mediastinal abscess with no pleural effusion 2 month after procedure. b Esophagography shows decrease of esophageal mediastinal abscess, and then the drainage tube was removed 2 months after procedure. c–d The chest CT scan and esophagography shows almost disappearance of mediastinal abscess 2.7 months after stent placement

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median ± interquartile range (IQR), and analyzed by student t test. Qualitative data were expressed in percentage, and data between Group A and Group B were analyzed by Fisher’s exact test. Patency rate was compared by Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) Test (GraphPad Software, Inc., USA). Statistical significance was considered when p < 0.05.

Results

General information

A total of 37 patients with esophageal fistula combined with stricture were enrolled in this study, including 26 patients in group A and 11 patients in group B.. The ages of the patients ranged from 43 years to 77 years, for a median age of 62.0 years. Twenty-three patients showed a fever, for a median temperature of 38.6 °C (IQR: 38.4 to 39.0 °C). The median course of disease before referral to our department was 6.0 months (IQR: 3.0 to 17.5 months). The median interval between clinical symptom and diagnosis of fistula was 2.0 months (IQR: 1.0–5.0 months). The median interval between diagnosis of fistula and interventional treatment was 0.5 months (IQR: 0.2–3.0 months). There were 23 cases of esophageal mediastinal fistula and 14 cases of esophagopleural fistula. All patients showed esophageal stricture simultaneously. Twenty-six patients received stents and three tubes placement in group A, and 11 patients received three tubes placement in group B. There was no significant difference in characteristic data between two groups before interventional treatment (all p > 0.05, Table 1).

Besides, eleven patients received chemotherapy or radiotherapy, and six patients received chemotherapy and radiotherapy. For patients with squamous cell carcinoma and HER-2 negative adenocarcinomas, fluorouracil + cisplatin, or paclitaxel/docetaxel + cisplatin/nedaplatin were used. Patients with HER-2 positive adenocarcinoma were treated with trastuzumab combined with fluorouracil + cisplatin. Radiotherapy was performed for 2–30 times for each patient. One patient with metastatic tumor in lung received iodine-125 seeds implantation therapy.

Interventional procedure outcomes

Three tubes were placed successfully for all patients (100%). One patient failed in stent placement owing to complete occlusion, for a technical success rate of 96.2% (25/26). A total of 42 covered esophageal stents were placed in group A, for a median diameter of 18 mm (IQR: 18–20 mm), median length of 120 mm (IQR: 100–120 mm). Only one stent was placed in each of the 16 patients. For the remaining 10 patients, two or more stents were used due to stent restenosis or migration. Stent insertion was technically successful in the remained 25 patients, with satisfactory expansion and appropriate position. Complete block of esophageal fistula was confirmed by esophagography in 24 patients immediately after covered stent placement, and one patient showed a small amount of fistula between the stents and the wall of the esophagus. There was no significant difference between group A and group B regarding average times of admissions, mean hospitalization days, or total hospitalization days. However, at the time of discharge, 6 patients were fed with nutrition tube and 20 patients were fed a normal diet in group A. However, 9 patients were fed with nutrition tube in group B, which was significantly lower rate of normal diet than that in group A (p = 0.0023, Table 2). Seventeen esophageal stents were successfully removed from 10 patients due to stent restenosis (n = 9), migration (n = 6), and healing of fistula and stenosis relief (n = 2), with no major complications. The median retention duration was 3.3 months (IQR:1.8, 7.0 months) and 3.4 months (IQR:1.4, 5.0 months) for stent and abscess drainage tubes, respectively.

Complications

No esophagus perforation was observed during procedure. One perioperative death due to massive hemorrhage was observed 21 days after stent placement. Except for one perioperative death, two patients died of massive digestive bleeding in group A during follow up. Stent migration was found in 8 patients, for a migration rate of 30.8% (8/26). The migrated stent was adjusted by using string. Five patients showed stent restenosis, for a restenosis rate of 19.2% (5/26). All migrated or stenotic stents were adjusted or replaced for 0 to 3 times (median: 1 time). Occlusion of abscess drainage tube was found in one patient. The abscess drainage tube was adjusted or replaced for 0 to 7 times (median: 1 time). One patient showed slight fistula due to poor adhesion after stent placement (Table 3).

Follow-up

Thirty-five patients were successfully followed up, and 2 patients were lost to follow up in group A. Chest CT showed that the abscess cavity was decreased or disappeared after a median duration of 114.5 days in 17 cases in group A, 4 cases showed decreased or disappeared abscess cavity after a median duration of 173.0 days in group B. At the day discharge, 20 patients showed normal diet per os in group A, and only 2 patients showed normal diet in group B. During follow up, patients in group A still showed a significant better condition of normal diet and lower dysphagia score than that in group B (p < 0.05). At this time, 11 patients in group A were still alive without severe symptom, and 5 patients in group B return to normal living conditions with no severe symptom. During follow up, 14 patients died of cancer recurrence, 3 patients died of massive digestive bleeding and 2 patients died of severe pulmonary infection. The median survivals were 14.8 months and 13.2 months for group A and group B, respectively.

Discussion

Malignant esophageal fistula combined with stricture can be found in patients with esophageal or esophagogastric carcinoma or anastomotic leakage/stricture after esophagectomy [1, 2]. Palliation presents a challenge with a poor prognosis and relatively high mortality [2, 4, 7,8,9,10,11]. Unfortunately, there is no optimal treatment protocol for those patients [2,3,4,5,6,7, 12]. Esophageal stents have been served as a palliative treatment for patients with esophageal diseases [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Management of esophageal fistula needs adequate elimination of contamination and effective drainage of the abscess cavity.

Covered esophageal stent placement and abscess drainage tube insertion was used in this study. Our data indicated that fluoroscopically guided placement of metallic covered stents or three tubes are safe. After covered stent placement, the abscess cavity is also allowed to continuously drainage by abscess drainage tube. According to our experience, the esophageal stent placed in the stricture site often show incomplete expansion, and show complete expansion and can close the fistula about 3–5 days later. We recommend patients received nasal feeding nutrition after stents placement, and start normal diet if the fistula disappears. All patients were suitable for placement of covered stents and three tubes placement. Unfortunately, patients in group B did not receive stents placement because of economic pressure or reluctance to receive stent implantation. Those patients only received three tubes placement, and showed a worse condition of normal diet.

However, covered stent also bring certain related complications. All stents used in our study was covered, and stent migration was a common complication. Eight patients (30.8%) showed stent migration and 5 patients showed stent restenosis (19.2%). In other studies, stent migration rates ranged up to 19% for plastic covered stents and 22.7% for segmental covered stents [20, 21]. Compared with radioactive metal stent, our study showed a higher restenosis rate, indicating that radioactive metal stent may prevent stent restenosis induced by tumor progression [20].

There were some limitations in the current study. This was a retrospective study and the enrolled patient number was relatively small. Patients were divided into different groups according to their choice based on doctors’ advice, treatment willingness and economic endurance. A prospective randomized study is needed to reach a positive and convincing clinical conclusion.

Conclusions

Covered metallic stent placement is safe, feasible and efficacious for treatment of esophageal fistula and stricture, with a better condition of normal diet than patients only received three tubes placement.

Availability of data and materials

For further details, the corresponding author can be contacted.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computerized tomography

- IQR:

-

Mean ± interquartile range

References

Safranek PM, Cubitt J, Booth MI, Dehn TC. Review of open and minimal access approaches to oesophagectomy for cancer. Br J Surg. 2010;97(12):1845–53.

Pennathur A, Luketich JD. Resection for esophageal cancer: strategies for optimal management. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85(2):S751–6.

Toussaint E, Eisendrath P, Kwan V, Dugardeyn S, Deviere J, Le Moine O. Endoscopic treatment of postoperative enterocutaneous fistulas after bariatric surgery with the use of a fistula plug: report of five cases. Endoscopy. 2009;41(6):560–3.

Zheng YZ, Dai SQ, Shan HB, Gao XY, Zhang LJ, Cao X, et al. Managing esophageal fistulae by endoscopic transluminal drainage in esophageal cancer patients with superior mediastinal sepsis after esophagectomy. Chin J Cancer. 2013;32(8):469–73.

Leers JM, Vivaldi C, Schafer H, Bludau M, Brabender J, Lurje G, et al. Endoscopic therapy for esophageal perforation or anastomotic leak with a self-expandable metallic stent. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(10):2258–62.

Lippert E, Klebl FH, Schweller F, Ott C, Gelbmann CM, Scholmerich J, et al. Fibrin glue in the endoscopic treatment of fistulae and anastomotic leakages of the gastrointestinal tract. Int J Color Dis. 2011;26(3):303–11.

Lang H, Piso P, Stukenborg C, Raab R, Jahne J. Management and results of proximal anastomotic leaks in a series of 1114 total gastrectomies for gastric carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26(2):168–71.

Dougenis D, Petsas T, Bouboulis N, Leukaditou C, Vagenas C, Kardamakis D, et al. Management of non resectable malignant esophageal stricture and fistula. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1997;11(1):38–45.

Junemann-Ramirez M, Awan MY, Khan ZM, Rahamim JS. Anastomotic leakage post-esophagogastrectomy for esophageal carcinoma: retrospective analysis of predictive factors, management and influence on longterm survival in a high volume Centre. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;27(1):3–7.

Blewett CJ, Miller JD, Young JE, Bennett WF, Urschel JD. Anastomotic leaks after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: a comparison of thoracic and cervical anastomoses. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;7(2):75–8.

Hofstetter W, Swisher SG, Correa AM, Hess K, Putnam JB Jr, Ajani JA, et al. Treatment outcomes of resected esophageal cancer. Ann Surg. 2002;236(3):376–84.

Brinster CJ, Singhal S, Lee L, Marshall MB, Kaiser LR, Kucharczuk JC. Evolving options in the management of esophageal perforation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77(4):1475–83.

Fischer A, Thomusch O, Benz S, von Dobschuetz E, Baier P, Hopt UT. Nonoperative treatment of 15 benign esophageal perforations with self-expandable covered metal stents. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(2):467–72.

Peters JH, Craanen ME, van der Peet DL, Cuesta MA, Mulder CJ. Self-expanding metal stents for the treatment of intrathoracic esophageal anastomotic leaks following esophagectomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(6):1393–5.

Freeman RK, Van Woerkom JM, Ascioti AJ. Esophageal stent placement for the treatment of iatrogenic intrathoracic esophageal perforation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83(6):2003–7 discussion 7-8.

Hunerbein M, Stroszczynski C, Moesta KT, Schlag PM. Treatment of thoracic anastomotic leaks after esophagectomy with self-expanding plastic stents. Ann Surg. 2004;240(5):801–7.

Kauer WK, Stein HJ, Dittler HJ, Siewert JR. Stent implantation as a treatment option in patients with thoracic anastomotic leaks after esophagectomy. Surg Endosc. 2008;22(1):50–3.

Siersema PD. Treatment of esophageal perforations and anastomotic leaks: the endoscopist is stepping into the arena. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61(7):897–900.

White RE, Mungatana C, Topazian M. Expandable stents for iatrogenic perforation of esophageal malignancies. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7(6):715–9.

Bi Y, Li J, Yi M, Yu Z, Han X, Ren J. Self-expanding segmental radioactive metal stents for palliation of malignant esophageal strictures. Acta Radiol. 2019;284185119886315.

Bethge N, Vakil N. A prospective trial of a new self-expanding plastic stent for malignant esophageal obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(5):1350–4.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81501569). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design: XH and JR; Data collection: ZY; Manuscript drafting:: YB and MY; Statistical analysis: YB and MY; Administrative support: XH and JR; all authors discussed the results and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University. Written informed consents were obtained from all patients.

Consent for publication

Written informed consents were obtained from the patients for publication. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bi, Y., Yi, M., Yu, Z. et al. Covered metallic stent for the treatment of malignant esophageal fistula combined with stricture. BMC Gastroenterol 20, 248 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-020-01398-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-020-01398-6