Abstract

Background

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) to remove colon polyps is increasingly common in patients taking antithrombotic agents. The safety of EMR with submucosal saline injection has not been clearly demonstrated in this population.

Aims

The present study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of submucosal injection of saline–epinephrine versus hypertonic saline in colorectal EMR of patients taking antithrombotic agents.

Methods

This study enrolled 204 patients taking antithrombotic agents among 995 consecutive patients who underwent colonic EMR from April 2012 to March 2018 at Ureshino Medical Center. Patients were divided into two groups according to the injected solution: saline–epinephrine or hypertonic (10%) saline (n = 102 in each group). Treatment outcomes and adverse events were evaluated in each group and risk factors for immediate and post-EMR bleeding were investigated.

Results

There were no differences between groups in patient or polyp characteristics. The main antithrombotic agents were low-dose aspirin, warfarin, and clopidogrel. Propensity-score matching created 80 matched pairs. Adjusted comparisons between groups showed similar en bloc resection rates (95.1% with saline–epinephrine vs. 98.0% with hypertonic saline). There were no significant differences in adverse events (immediate EMR bleeding, post-EMR bleeding, perforation, or mortality) between groups. Multivariate analyses revealed that polyp size over 10 mm was associated with an increased risk of immediate EMR bleeding (odds ratio 12.1, 95% confidence interval 2.0–74.0; P = 0.001).

Conclusions

Two tested solutions in colorectal EMR were considered to be both safe and effective in patients taking antithrombotic agents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Endoscopic polypectomy for colon lesions effectively reduces the risk of colorectal cancer [1, 2)]. Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), which involves the injection of fluid to expand the submucosal space, simplifies polypectomy and reduces the risk of adverse events [3,4,5,6,7,8,9)]. Post-polypectomy bleeding is the most common complication of endoscopic polypectomy, with reported incidences ranging from 0.65 to 8.6% [10,11,12,13,14,15,16)]. EMR with submucosal injection of epinephrine–saline or hypertonic saline solution enhances complete resection of lesions compared with simple polypectomy [17,18,19,20)]. Although both epinephrine solution and hypertonic saline have hemostatic effects that can prevent post-EMR bleeding, the efficacy of these two solutions in decreasing post-EMR bleeding in patients taking antithrombotic agents has not been clearly demonstrated [21,22,23,24,25)].

Antithrombotic agents, including antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants, are widely used to reduce the risk of thromboembolic events in patients with cerebro- and cardiovascular disease, deep vein thrombosis, and hypercoagulable status [26,27,28,29)]. Post-polypectomy bleeding after EMR is more commonly induced by anticoagulants than by antiplatelet agents [11, 30,31,32)]. Several clinical practice guidelines on gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures published in Europe, North America, Japan, and the Asia Pacific recommend that antithrombotic agents, especially aspirin, be continued during colonoscopic polypectomy. These clinical guidelines recommend that anticoagulants be discontinued during colorectal polypectomy in patients with low thromboembolic risks and be replaced with heparin for those with high thromboembolic risks [33,34,35,36,37)]. Several studies demonstrated that heparin replacement increased post-polypectomy and/or post-EMR bleeding compared with procedures without heparin or with original anticoagulants [28, 38, 39)].

Several solutions, including polidocanol, hyaluronic acid, and epinephrine–saline solution, have been used in colorectal EMR. However, the safety of these solutions has not been clearly demonstrated during EMR in patients taking antithrombotic agents [21,22,23,24,25)]. The aims of the present retrospective study were i) to compare the clinical outcomes of prophylactic injection of submucosal saline–epinephrine versus hypertonic saline for colorectal EMR in patients taking antithrombotic agents and ii) to identify the risk factors for immediate and post-EMR bleeding in these patients.

Methods

Patients

This retrospective chart review included 204 patients taking antithrombotic agents among 995 consecutive patients who underwent colonic EMR at the National Hospital Organization Ureshino Medical Center from April 2012 to March 2018. Patients >20 years of age who fulfilled the following criteria were candidates for the study: i) polyp diameter < 20 mm; ii) use of antithrombotic agents, including antiplatelet agents (low-dose aspirin, clopidogrel, ticlopidine, and cilostazol) and anticoagulants (warfarin and direct oral anticoagulants); and iii) normal coagulogram (platelet count: 140,000–379,000/μL, prothrombin time international ratio: 1.5–2.6). Patients with polyp diameter > 20 mm, abnormal coagulogram, and/or impaired normal blood clotting were excluded. Informed consent for the procedures was obtained from all patients who underwent colorectal EMR. The present study was conducted according to the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects. The study protocol and the consent procedure were approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the National Hospital Organization Ureshino Medical Center (approval number 18–17).

Procedure of EMR

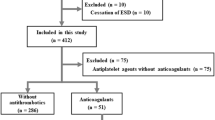

During the study period, 10 endoscopists with more than 3 years of experience in gastrointestinal colonoscopy performed colorectal EMR procedures using submucosal injection of either saline–epinephrine (0.01%) or hypertonic saline (10% NaCl), according to the judgment of the endoscopist. Patients were divided into two groups: the saline–epinephrine group (Group A) and the hypertonic saline group (Group B) (Fig. 1). The EMR procedure was performed with a colonoscope (PCF-Q260AZI; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), snare (SnareMaster; Olympus), and electrosurgical unit (VIO 300, ERBE; Elektronedizin, Tübingen, Germany), with appropriate use of butylscopolamine or glucagon. Sedation was not used, except in patients with procedure-related pain or sedation request; in these patients, diazepam (5–10 mg), midazolam (0.05–0.1 mg/kg), pentazocine (15 mg), or pethidine hydrochloride (35 mg) was administered with monitoring of cardiorespiratory function [40].

After injection of saline–epinephrine (Fig. 2) or hypertonic saline (Fig. 3) into the submucosa with needle forceps to create an adequate mucosal bulge, the colorectal polyp was snared and resected [17, 22)]. Prophylactic clipping was performed in all patients. When bleeding was clinically suspected after EMR, emergency colonoscopy was performed to achieve hemostasis with hemoclips and/or electrocoagulation [19)].

Colorectal endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) with injection of hypertonic saline (10% NaCl). a Semi-pedunculated polyp in cecum, 8 mm in diameter. b Injection of hypertonic saline (10% NaCl) for submucosal lifting. c Mucosal resection of polyp with the snare. d Post-EMR findings after en bloc resection

Clinical outcomes

Information on antithrombotic agents was recorded, including type, number, and management (continuation, cessation, or replacement) and comorbidity including Charlson comorbidity score was detected. Information on polyp lesions (size, location, and histological and macroscopic classifications), the endoscopist (specialist or trainee), and treatment outcomes (procedure time and en bloc resection rate) were reviewed after EMR. Specialist endoscopists were defined as those who had performed more than 40 EMR procedures over a period of at least 3 years after attaining the required fundamental skills and knowledge [41, 42)]. Immediate EMR bleeding was defined as hemorrhage during the procedure; post-EMR bleeding was defined as bleeding that occurred at least 1 h after the procedure. Adverse events of immediate EMR bleeding, post-EMR bleeding, perforation, and mortality within 30 days were recorded. Results are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD).

The χ2 test was used to identify differences in the effectiveness rate between the two groups. Student’s t test was used for unpaired data to determine differences in means between the two groups. As indicated in Fig. 1, the two groups were compared after propensity-score matching. Propensity-score-matching analysis was used to control factors that might influence EMR treatment outcomes and adverse events. The two groups were matched in a 1:1 ratio (Group A, n = 80; Group B, n = 80) with propensity-score matching adjusted for five covariates (age, sex, anticoagulant agents, antiplatelet agents, and endoscopist) to minimize inherent bias (Table 5). This model yielded a c statistic of 0.67, indicating the ability to differentiate between Groups A and B. The caliper width of propensity-score matching was 0.05. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression was performed to assess risk factors for immediate and post-EMR bleeding, with the explanatory variables of age, sex, anticoagulant agents, antiplatelet agents, multiple agents, heparin bridge therapy, polyp size, number of polyps, histological classification, endoscopist, and type of injection. All statistical analyses were performed with JMP version 13.0.0 (SAS Institute, Tokyo, Japan).

Results

Among 995 consecutive patients who underwent colorectal EMR, 204 patients taking antithrombotic agents were included. Among these, 102 received saline–epinephrine injection and were allocated to Group A and 102 received hypertonic saline injection and were allocated to Group B (Fig. 1). There was no significant difference in baseline characteristics between the groups before propensity-score matching (Table 1). The median age of patients was 73.7 ± 8.7 years in Group A and 73.7 ± 8.3 years in Group B; 84 (82.4%) patients in each group were men. There were no significant differences between groups in the various comorbidities and Charlson comorbidity score. EMR procedures were performed by trainees more frequently in Group A than in Group B (72/102 vs. 50/102, respectively; P = 0.003).

Table 2 summarizes the types and management of antithrombotic agents. The main antithrombotic agents were low-dose aspirin, warfarin, and clopidogrel. The proportion of patients taking anticoagulant agents was significantly higher in Group B (39.2%) than in Group A (20.6%; P = 0.006). Before colorectal EMR, there was no significant difference between groups in the percentage of patients whose warfarin was replaced with heparin (14.7% in Group A vs. 23.5% in Group B) or with direct oral anticoagulants (1.0% in both groups). There was also no difference between groups in the percentage of patients whose cilostazol was replaced with other antiplatelet agents (14.7% vs. 10.8%).

As shown in Table 3, the colonic polyp characteristics were not different between the groups. The average number of tumors was 2.6 ± 1.9 in Group A and 2.9 ± 2.6 in Group B. The average tumor size was 10.0 ± 5.8 mm and 10.0 ± 5.0 mm. Regarding polyp location, sigmoid polyps were most common in both groups (34.3% vs. 33.3%). Macroscopically, the 0–Is type was most common in both groups (32.3% vs. 36.3%); adenoma was the most common histological classification (78.4% in both groups).

Propensity-score matching created 80 matched pairs in the present study. As shown in Table 4, before propensity-score matching, significant differences were present in the proportion of patients taking anticoagulant agents (20.6% in Group A vs. 39.2% in Group B, P = 0.006) and of trainee endoscopists (70.6% vs. 49.0%, P = 0.003). Propensity-score matching averaged the differences in five covariates. Table 5 shows EMR treatment outcomes and adverse events after propensity-score matching. Procedure time was similar in both groups (29.5 ± 19.5 s vs. 31.0 ± 18.8 s, P = 0.65). The percentage of patients who underwent en bloc resection was not different between groups (95.0% vs. 97.5%, P = 0.68). Regarding adverse events, there were no significant differences in the incidence of immediate EMR bleeding (7.5% vs. 2.5%, P = 0.28), post-EMR bleeding (8.8% vs. 3.8%, P = 0.33), time to post-EMR bleeding (1.7 ± 1.3 days vs. 2.3 ± 1.5 days, P = 0.58), incidence of perforation (0.0% in both groups, P = 1.00), or mortality rate (0.0% in both groups, P = 1.00). No cerebrovascular events occurred during or after EMR procedures in the present study. All patients with immediate EMR bleeding or post-EMR bleeding were successfully treated with endoscopic hemostasis.

Table 6 lists the risk factors for immediate and post-EMR bleeding among patients taking antithrombotic agents. Only polyp size greater than 10 mm increased the risk of immediate EMR bleeding in univariate analysis (odds ratio, 5.57; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.27–24.5; P = 0.024) and in multivariate analysis (odds ratio, 12.1; 95% CI, 2.0–74.0; P = 0.001). No risk factor for post-EMR bleeding was detected in the present study. The use of saline–epinephrine versus hypertonic solution for injection was not related to the risk of bleeding during or after colorectal EMR.

Discussion

EMR is a standard procedure associated with substantial adverse events in the treatment of gastrointestinal lesions. Bleeding is the most common adverse event of colorectal EMR [11,12,13,14,15,16,17)]. Submucosal injection of epinephrine–saline solution, which is an effective method for colorectal EMR, especially in flat or sessile lesions, is widely used because of its simplicity, low cost, and wide availability [21)]. Hypertonic saline injection, which creates a relatively longer-lasting submucosal cushion because of its viscosity, enables EMR without apparent tissue damage [25)].

In the present study, both epinephrine–saline solution and hypertonic saline solution were effective for EMR in patients taking antithrombotic agents. Treatment outcomes (procedure time and rate of en bloc resection) were similar for EMR with both solutions. Regarding adverse events, no perforation or fatality related to EMR was observed in the present study; the incidence of immediate EMR bleeding (7.5% in Group A vs. 2.5% in Group B), post-EMR bleeding (8.8% vs. 3.8%), and time to post-EMR bleeding (1.7 ± 1.3 days vs. 2.3 ± 1.5 days) did not differ with injection of epinephrine–saline solution versus hypertonic saline solution. All bleeding resolved with endoscopic hemostatic methods, including high-frequency soft coagulation and/or hemoclip.

Several previous studies have reported bleeding rates of 0.65 to 8.6% after simple colorectal polypectomy with or without antithrombotic agents [10,11,12,13,14,15,16)]. The reported rate of post-colorectal EMR bleeding is 9.3 to 26.3% in previous studies on the use of antithrombotic agents [18, 28, 29, 43)]. The results in the present study regarding bleeding after EMR in patients taking antithrombotic agents are consistent with these previous studies and indicate the safety of colorectal EMR with injection of epinephrine–saline or hypertonic saline in patients taking antithrombotic agents. Lesion size over 10 mm was a risk factor for immediate and post-EMR bleeding in multivariate analysis in the present study. The type of solution used for injection in the EMR procedure was not a risk factor for bleeding, indicating that both epinephrine–saline and hypertonic saline can be used for colorectal EMR.

The present retrospective chart review had several limitations. The type of antithrombotic agent taken and the skill of the colorectal EMR endoscopist differed between groups. Submucosal injection of epinephrine-saline or hypertonic saline for EMR was selected by the endoscopist in the present study, and the trainee tended to use the solution of epinephrine-saline because of speculated advantage for prevention of bleeding of EMR. Propensity-score matching was used for statistical analysis to reduce the bias between groups including the endoscopist’s bias [44)]. The present study did not include polyps larger than 20 mm, although lesion size was a risk factor for bleeding during EMR.

Conclusions

Colonic EMR procedures with the two tested solutions in the present study were safe and effective in patients taking antithrombotic agents as there were no serious complications with submucosal injection of epinephrine–saline or hypertonic saline.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- EMR:

-

Endoscopic mucosal resection

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O’Brien MJ, et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:687–96.

Citarda F, Tomaselli G, Capocaccia R, Barcherini S, Crespi M. Efficacy in standard clinical practice of colonoscopic polypectomy in reducing colorectal cancer incidence. Gut. 2001;48:812–5.

Kaltenbach T, Soetikno R. Endoscopic resection of large colon polyps. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2013;23:137–52.

Tanaka S, Kashida H, Saito Y, et al. JGES guidelines for colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection/endoscopic mucosal resection. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:417–34.

Kudo S. Endoscopic mucosal resection of flat and depressed types of early colorectal cancer. Endoscopy. 1993;25:455–61.

Uraoka T, Saito Y, Matsuda T, et al. Endoscopic indications for endoscopic mucosal resection of laterally spreading tumours in the colorectum. Gut. 2006;55:1592–7.

Ichise Y, Horiuchi A, Nakayama Y, Tanaka N. Prospective randomized comparison of cold snare polypectomy and conventional polypectomy for small colorectal polyps. Digestion. 2011;84:78–81.

Kudo S, Tamegai Y, Yamano H, et al. Endoscopic mucosalresection of the colon: the Japanese technique. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2001;11:519–35.

Watanabe T, Itabashi M, Shimada Y, et al. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2010 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2012;17:1–29.

Heldwein W, Dollhopf M, Rösch T, et al. The Munich Polypectomy study (MUPS): prospective analysis of complications and risk factors in 4000 colonic snare polypectomies. Endoscopy. 2005;37:1116–22.

Sawhney MS, Salfiti N, Nelson DB, Lederle FA, Bond JH. Risk factors for severe delayed postpolypectomy bleeding. Endoscopy. 2008;40:115–9.

Oka S, Tanaka S, Kanao H, et al. Current status in the occurrence of postoperative bleeding, perforation and residual/local recurrence during colonoscopic treatment in Japan. Dig Endosc. 2010;22:376–80.

Nakajima T, Saito Y, Tanaka S, et al. Current status of endo-scopic resection strategy for large, early colorectal neoplasia in Japan. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3262–70.

Rutter MD, Nickerson C, Rees CJ, Patnick J, Blanks RG. Risk factors for adverse events related to polypectomy in the English bowel Cancer screening Programme. Endoscopy. 2014;46:90–7.

Niikura R, Yasunaga H, Yamada A, et al. Factors predicting adverse events associated with therapeutic colonoscopy for colorectal neoplasia: a retrospective nationwide study in Japan. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:971–82.

Aoki T, Yoshida S, Abe H, et al. Analysis of predictive factors for R0 resection and immediate bleeding of cold snare polypectomy in colonoscopy. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0213281.

Shinozaki S, Kobayashi Y, Hayashi Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of cold versus hot snare polypectomy for resecting small colorectal polyps: systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Endosc. 2018;30:592–9.

Horiuchi A, Hosoi K, Kajiyama M, Tanaka N, Sano K, Graham DY. Prospective, randomized comparison of 2 methods of coldsnare polypectomy for small colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:686–92.

Tsuruta S, Tominaga N, Ogata S, et al. Risk factors for delayed hemorrhage after colonic endoscopic mucosal resection in patients not on antithrombotic therapy: retrospective analysis of 3,844 polyps of 1,660 patients. Digestion. 2019;100:86–92.

Yamamoto K, Shimoda R, Ogata S, et al. Perforation and postoperative bleeding associated with endoscopic submucosal dissection in colorectal tumors: an analysis of 398 lesions treated in Saga, Japan. Intern Med. 2018;57:2115–22.

Facciorusso A, Di Maso M, Antonino M, et al. Polidocanol injection decreases the bleeding rate after colon polypectomy: a propensity score analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:350–8.

Lee SH, Chung IK, Kim SJ, et al. Comparison of postpolypectomy bleeding between epinephrine and saline submucosal injection for large colon polyps by conventional polypectomy: a prospective randomized, multicenter study. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2973–7.

Sanchez-Yague A, Kaltenbach T, Raju G, et al. Advanced endoscopic resection of colorectal lesions. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2013;42:459–77.

Yoshida N, Naito Y, Kugai M, et al. Efficacy of hyaluronic acid in endoscopic mucosal resection of colorectal tumors. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:286–91.

Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Kashimura K, et al. Comparison of various sub-mucosal injection solutions for maintaining mucosal elevation during endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 2004;36:579–83.

Yamaguchi D, Sakata Y, Tsuruoka N, et al. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in Japanese patients prescribed antithrombotic drugs: differences in trends over time. Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61:1055–62.

Yamaguchi D, Sakata Y, Tsuruoka N, et al. Characteristics of patients with non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding taking antithrombotic agents. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:30–6.

Inoue T, Nishida T, Maekawa A, et al. Clinical features of post-polypectomy bleeding associated with heparin bridge therapy. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:243–9.

Ishigami H, Arai M, Matsumura T, et al. Heparin-bridging therapy is associated with a high risk of post-polypectomy bleeding regardless of polyp size. Dig Endosc. 2017;29:65–72.

Watabe H, Yamaji Y, Okamoto M, et al. Risk assessment for delayed hemorrhagic complication of colonic polypectomy: polyp-related factors and patient-related factors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:73–8.

Kim HS, Kim TI, Kim WH, et al. Risk factors for immediate postpolypectomy bleeding of the colon: a multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1333–41.

Hui AJ, Wong RM, Ching JY, Hung LC, Chung SC, et al. Risk of colonoscopic polypectomy bleeding with anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents: analysis of 1657 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:44–8.

Boustiere C, Veitch A, Vanbiervliet G, et al. Endoscopy and antiplatelet agents. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy. 2011;43:445–61.

Anderson MA, Ben-Menachem T, Gan SI, et al. Management of antithrombotic agents for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:1060–70.

Fujimoto K, Fujishiro M, Kato M, et al. Guidelines for gastroenterological endoscopy in patients undergoing antithrombotic treatment. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:1–14.

Chan FKL, Goh KL, Reddy N, et al. Management of patients on antithrombotic agents undergoing emergency and elective endoscopy: joint Asian Pacific Association of Gastroenterology (APAGE) and Asian Pacific Society for Digestive Endoscopy (APSDE) practice guidelines. Gut. 2018;67:405–17.

Kato M, Uedo N, Hokimoto S, et al. Guidelines for gastroenterological endoscopy in patients undergoing antithrombotic treatment: 2017 appendix on anticoagulants including direct Oral anticoagulants. Dig Endosc. 2018;30:433–40.

Kubo T, Yamashita K, Onodera K, et al. Heparin bridge therapy and post-polypectomy bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:10009–14.

Yanagisawa N, Nagata N, Watanabe K, et al. Post-polypectomy bleeding and thromboembolism risks associated with warfarin vs direct oral anticoagulants. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:1540–9.

Yamaguchi D, Yamaguchi N, Takeuchi Y, et al. Comparison of sedation between the endoscopy room and operation room during endoscopic submucosal dissection for neoplasms in the upper gastrointestinal tract. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:127.

Tsuji Y, Ohata K, Sekiguchi M, et al. An effective training system for endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric neoplasm. Endoscopy. 2011;43:1033–8.

Ono H, Yao K, Fujishiro M, et al. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Dig Endosc. 2016;28:3–15.

Yamashita K, Oka S, Tanaka S, et al. Use of anticoagulants increases risk of bleeding after colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6:E857–64.

D’Agostino RB Jr. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17:2265–81.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No specific grants from any funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors were received for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DY and KF designed the research; DY, YT, KI, TY, SY, AJ, ET, WY, HF, NT1, NT2, TM, KA and ST performed colorectal endoscopic mucosal resection procedure, acquired the patient data, and made substantial contributions to the conception; DY designed the work; DY and HY analyzed the data; DY and KF wrote the paper; KF was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read, have approved the submitted version and approved the final manuscript. All authors have agreed both to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This retrospective study was conducted according to the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects. The present study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of National Hospital Organization Ureshino Medical Center (approval number 18–17). No additional permissions were required to review the patient records, including the hospitals from which the records were obtained.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamaguchi, D., Yoshida, H., Ikeda, K. et al. Colorectal endoscopic mucosal resection with submucosal injection of epinephrine versus hypertonic saline in patients taking antithrombotic agents: propensity-score-matching analysis. BMC Gastroenterol 19, 192 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-019-1114-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-019-1114-x