Abstract

Background

To evaluate participant-related variables associated with missing assessment(s) at follow-up visits during a longitudinal research study.

Methods

This is a prospective, longitudinal, multi-site study of 196 acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) survivors. More than 30 relevant sociodemographic, physical status, and mental health variables (representing participant characteristics prior to ARDS, at hospital discharge, and at the immediately preceding follow-up visit) were evaluated for association with missed assessments at 3, 6, 12, and 24-month follow-up visits (89–95% retention rates), using binomial logistic regression.

Results

Most participants were male (56%), white (58%), and ≤ high school education (64%). Sociodemographic characteristics were not associated with missed assessments at the initial 3-month visit or subsequent visits. The number of dependencies in Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) at hospital discharge was associated with higher odds of missed assessments at the initial visit (OR: 1.26, 95% CI: 1.12, 1.43). At subsequent 6-, 12-, and 24 months visits, post-hospital discharge physical and psychological status were not associated with subsequent missed assessments. Instead, the following were associated with lower odds of missed assessments: indicators of poorer health prior to hospital admission (inability to walk 5 min (OR: 0.46; 0.23, 0.91), unemployment due to health (OR: 0.47; 0.23, 0.96), and alcohol abuse (OR: 0.53; 0.28, 0.97)) and having the preceding visit at the research clinic rather than at home/facility, or by phone/mail (OR: 0.54; 0.31, 0.96). Inversely, variables associated with higher odds of missed assessments at subsequent visits include: functional dependency prior to hospital admission (i.e. dependency with > = 2 Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs) (OR: 1.96; 1.08, 3.52), and missing assessments at preceding visit (OR: 2.26; 1.35, 3.79).

Conclusions

During the recovery process after hospital discharge, dependencies in physical functioning (e.g. ADLs, IADLs) prior to hospitalization and at hospital discharge were associated with higher odds of missed assessments. Conversely, other indicators of poorer health at baseline were associated with lower odds of missed assessments after the initial post-discharge visit. To reduce missing assessments, longitudinal clinical research studies may benefit from focusing additional resources on participants with dependencies in physical functioning prior to hospitalization and at hospital discharge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

There has been increasing interest in evaluating and reporting outcomes after hospital discharge in survivors of critical illness, including in clinical trials in this study population [1]. However, missing data are common in such studies. For example, a review of randomized trials published over a 6-month period in four high impact general medicine journals showed that some primary outcome data was missing for 89% of studies (n = 71), and that 18% of studies had missingness rates of more than 20% [2]. High rates of missing data detrimentally impacts statistical power and may introduce selection bias and loss of study validity [3, 4].

Loss to follow-up contributes to missing data, and many studies have examined factors associated with loss to follow-up to identify factors that could reduce attrition and the potential impact of attrition on study findings [5,6,7,8,9]. In addition, patients who are not lost to follow-up, but have missing data from incomplete study visits, also contribute to decreased precision and statistical power and potential selection bias. However, variables associated with missing data beyond loss to follow-up have not been well-studied. Understanding these can assist investigators in anticipating and tailoring follow-up efforts to minimize missing data in participants who attend their follow-up visits.

Survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) may be especially vulnerable to incomplete follow-up visits during longitudinal studies. Many of these patients have poor baseline health and quality of life [10,11,12,13], and often face new or worsened physical and psychological morbidities after hospitalization [14,15,16,17,18]. These impairments may present difficulties for survivors to participate in longitudinal studies. In addition, follow-up research assessments of these individuals tend to be lengthy involving multiple psychological and physical surveys and performance-based tests [19,20,21,22,23,24]. Hence, our objective is to use data from a multi-site study of ARDS survivors to evaluate patient-related variables associated with missed assessments during follow-up visits over the course of 2-years of longitudinal follow-up.

Methods

Study population and design

Mechanically ventilated patients, meeting the American-European Consensus Conference criteria for acute lung injury (ALI) that were in effect during the time of enrollment [25], were enrolled from 13 intensive care units from 4 teaching hospitals in Baltimore, MD (October 2004 – October 2007) [19]. Hereafter, we use the term ARDS, rather than ALI, to be consistent with the more recent Berlin definition [26]. Exclusion criteria included having > 96 h between ARDS diagnosis and enrollment, > 5 days mechanical ventilation before enrollment, pre-existing ARDS when transferred to a study ICU, pre-existing illness with a life expectancy of less than 6 months, any limitation of care at the time of enrollment (e.g. no cardiopulmonary resuscitation status), previous lung resection, inability to speak or understand English, and no fixed address. Prior to hospital discharge, study participants or proxies were administered a retrospective questionnaire on pre-hospitalization health status. Additionally, at hospital discharge, participants were assessed for independence in activities of daily living (ADLs, includes continence, toileting, and feeding), select health symptoms (e.g. shortness of breath), and discharge disposition including any health services required if discharged to home. Lastly, participants completed a battery of patient-reported and performance-based assessments (assessments listed under “Primary Outcome” section) of their physical and psychological status at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months after ARDS.

Follow-up patients from all 4 sites was conducted centrally by the coordinating center (Johns Hopkins University). The research staff collecting follow-up data underwent rigorous training and on-going quality assurance evaluations for conducting all participant assessments. Loss to follow-up in this cohort was minimized using published retention methods [27,28,29,30]. Retention strategies included: sending participants letter and magnet with study name/logo and phone number; reminder phone calls and letters for upcoming visits; meal vouchers, free parking or taxi rides; home visits to those unable to come to research clinic; thank you letters after visit; and newsletters and birthday cards to maintain contact between visits [19]. We also offered flexible visit hours (e.g. early or late in the day, and weekend) and home visits.

Primary outcome

At each of the 3, 6, 12 and 24 month follow-up visits, there were 15 participant assessments of physical and psychological status: 1) Activities of Daily Living (ADLs), 2) Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs, activities that require more complex thought, e.g. using telephone, managing finances) [31], 3) Hearing Handicap Inventory for Adults-Screening (HHIA-S) [32], 4) EQ-5D [33], 5) Short-Form 36 Questionnaire v2 (SF-36) [34], 6) Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [35], 7) Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) [36], 8) 6-min walk distance [37], 9) manual muscle testing (MMT) [38], 10) hand grip strength [39], 11) maximal inspiratory pressure (MIP) [40], 12) Telephone Interview of Cognitive Status (TICS) [41], 13) Sydney Swallowing Questionnaire (SSQ) [42], 14) anthropometric measurements, and 15) a collection of miscellaneous questions about employment, caregiver, etc. There were a small number of assessments that were not applicable to some participants (e.g. contraindications, comatose/cognitive status, amputated limbs or digits), and the number of possible assessments were reduced from maximum of 15. For the purposes of this analysis, assessments that were missed for reasons unrelated to participant factors (e.g. staff or equipment unavailable to conduct assessment) were considered “not applicable” and the total number of possible assessments was modified. Partially completed assessments (i.e. individual surveys or tests) were not considered missed. Reasons for missed or incomplete visits were categorized as due to the physical status of the participant (poor physical condition cited as the reason for not completing the assessment, although no explicit contraindication was present), refusal, lost contact, and other.

The outcome of interest was the number of missed assessments out of the number of possible assessments at each follow-up visit. Participants who missed an entire visit are included in analyses and considered to have missed 100% of the assessments at that visit.

Variables evaluated for association with missed assessments

Several baseline and pre-hospitalization variables were considered including participant demographics (age, sex, race, and education level), unemployment due to health condition, whether or not the participant resided at home without healthcare services, inability to walk at least 5 min, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [43], Functional Comorbidity Index (FCI) [44], and retrospectively collected baseline ADLs, IADLs, EQ-5D and SF-36. History of excessive alcohol use, illicit drug use, and any psychiatric comorbidity were collected from medical record. At hospital discharge, patients were evaluated for shortness of breath, ADLs, and discharge location. At each follow-up visit the following variables were evaluated: ADLs, IADLs, shortness of breath, participant living location, HHIA-S score, unemployment due to health, EQ-5D Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) (range: 0 to 100; higher score is better) and utility scores (range: − 0.11 to 1.0; higher score is better), SF-36 Physical Component Score (PCS) and Mental Component Score (MCS) (mean of 50, SD = 10; higher score is better), HADS anxiety and depression subscales scores (for each, range: 0 to 21; lower score is better, with scores ≥8 indicating substantial symptoms), IES-R score (range: 0 to 4; lower score is better ≥1.6 indicating substantial symptoms), 6-min walk test (percent of predicted value), MMT strength (score range: 0 to 60; higher score is better), hand grip strength (percent of predicted value), MIP (percent of predicted value), missing at least 1 assessment, and whether all data was collected at the research clinic (vs. via phone or mail, or visit to the participant’s home or long-term care facility). For all time-points, ADLs variable was defined as number of ADLs dependencies (out of a possible six activities) or dichotomized as ≥1 vs. 0 ADL dependencies. Similarly, the IADLs variable was defined as number of IADLs dependencies (out of a possible eight activities) or dichotomized as ≥2 vs. < 2 IADLs dependencies.

Analysis

For all patients at all follow-ups, we assumed that the outcome, the number of missed assessments, followed a Binomial distribution with required parameters: the total number of possible assessments and the mean, the probability of a missed assessment. Assuming the outcome follows the Binomial distribution implies that the probability of a missed assessment is the same for all possible assessments for the patient at the given follow-up. To quantify the association between the probability of a missed assessment (i.e. the mean of the outcome variable) with the a priori identified exposure variables, Binomial logistic regression models were used that accounted for variation in the total number of possible assessments across patients and follow-ups [45, 46]. More details on the Binomial logistic regression model can be found in the Additional file 1. In the Binomial logistic regression model, associations were quantified using odds ratio, i.e. the relative odds of a missed assessment per unit change in the exposure variable of interest. Standard errors for the odds ratios were estimated using robust variance estimates to account for the potential over- or under-dispersion in the assumed Binomial variance. First, pre-ARDS baseline and hospital discharge variables were correlated with the number of missed assessments at the initial follow-up at 3-months via bivariable Binomial regression models. For evaluating missed assessments across 6-, 12-, and 24-months, longitudinal Binomial logistic regression models fit with generalized estimating equations with an exchangeable correlation structure were used. The longitudinal models included main effects for follow-up time, exposure and their interaction. For variables where the relationship did not vary over time, the interaction term was dropped from subsequent models. Exposure variables were selected for inclusion in final multivariable models based on p < 0.20 for their univariable association with the outcome. If two definitions of the same variable were significant at p < 0.20 (for example, ≥1 ADL and number of ADLs), the one with the stronger association (i.e., smaller p-value) was used in the multivariable model.

There was minimal missing data for baseline and discharge characteristics. However, in the longitudinal models, exposures measured at the prior visit were included (i.e. 3-month IADLs as an exposure for missed assessments at 6-months) and could contain missing data. In these models, an indicator for whether or not the exposure was assessed at the prior visit was included as well as the interaction between this indicator and the exposure. Linearity of the association of each continuous exposure variable was assessed using locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOWESS) and restricted cubic splines, and there were no continuous exposures for which the linearity assumption was strongly violated. Standard regression diagnostics were used to assess model fit (evaluated by comparing predicted versus observed values and comparing quasi-information criteria (QIC) between multivariable models), influential data points (evaluated by Cooks D), and multicollinearity (evaluated by Variance Inflation Factors (VIFS)) (See Additional file 1: Table S2 for results). Logit of proportion of missed assessments was calculated for each person at each time-point in order to visualize the associations between the outcome variable and significant variables. Logit of proportion of missed assessments was undefined when probability was 0 or 1; therefore these logits were set to − 4 and 4, respectively, for the purpose of these illustrations. Figures were then created by calculating the univariable means of the logit of proportion of missed assessment with corresponding 95% confidence intervals or regression line, where appropriate.

A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance in the final multivariable models. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3.

Results

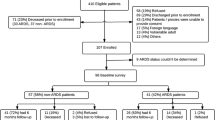

The study population was comprised of 196 participants who survived to 3-months and consented for 2-year longitudinal follow-up (Fig. 1). The majority of participants were male (56%), white (58%), and had no more than high school education (64%) (Table 1). Some participants had a history of alcohol abuse (25%), drug abuse (33%), or other psychiatric comorbidity (27%) prior to hospitalization. During follow-up, survivors generally experienced some improvement in health status (Table 2); for instance, the proportion of participants living at home without services increased from 63% at 3-months to 85% at 24-months. Only a small proportion of participants had completely missed visits (ranging from 11% at 3-month visit to 5% at 6- and 24-month visit), but incomplete visits (i.e. missing at least 1 of 15 assessments during the comprehensive visit) were more common (ranging from 48% at 3-month visit to 22% at 24-month visit) (Fig. 1, see Additional file 1: Table S1 for summary of missed assessment by outcome).

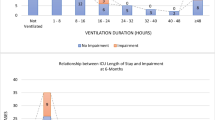

At 3-month follow-up, 105 (54%) of 196 participants missed at least 1 of the possible assessments. The median (interquartile range [IQR]) total number of possible assessments was 15 (15, 15) with a median (IQR) percent of missed assessments 7% (0, 33%). The most common reason for missing assessments was participant’s physical status (e.g. hospitalized, illness, fatigued) (46% of visits), followed by other reasons (e.g. incarcerated, lives too far, lacks time) (23%), refusal (18%), and lost contact with participant (13%). Of the 21 a priori variables evaluated for association with missed assessments at 3-month follow-up, 4 were included in the multivariable model (Table 3). Only dependencies in ADLs at hospital discharge (odds ratio (OR) of 1.26 [95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 1.12, 1.43; p = < 0.001] per 1 additional dependency) was independently associated with missed assessments at 3-month visit. Plots to visualize these associations are available in Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Between 6 and 24 month follow-up, 103 (56%) of 183 participants had at least one missing assessment. The median (IQR) total number of possible assessments was 15 (15, 15), 15 (15, 15) and 15 (15, 15) for the 6, 12, and 24 month follow-up, respectively. The median percent of missed assessments was relatively stable over time; 0% (0, 13%), 0% (0, 7%) and 0% (0, 7%) at 6, 12, and 24 month follow-up, respectively. The most common reason for a missing assessment was participant physical status (46% of visits), refusal (24%), other reasons (24%), and lost contact with participant (5%). Of the 37 a priori variables evaluated for association with missed assessments at 6-, 12-, 24-months, 7 were included in the multivariable model (Table 4). One variable, IES-R score ≥ 1.6, over time had significantly different associations with missed assessments at subsequent visit. However, when this variable and interaction term (with time) were added to the multivariable model, results remained consistent and goodness of fit decreased. Therefore, this variable was excluded from the multivariable model. Based on the final multivariable model evaluating missed assessments over 6–24 month follow-up, variables associated with lower odds of missed assessments were: poorer health at baseline: unable to walk 5 min (OR: 0.46; 95% CI: 0.23–0.91), unemployment due to health (0.47; 95% CI:0.23–0.96), and alcohol abuse (OR: 0.53; 95% CI: 0.28–0.97), and prior visit at the research clinic vs. any other location (OR: 0.54; 95% CI: 0.31–0.96). Conversely, variables associated with higher odds of missed assessments were: ≥2 IADL dependencies prior to hospital admission (OR 1.96; 95% CI: 1.08–3.52) and having missed assessments at the prior follow-up (OR 2.26; 95% CI: 1.35–3.79). Plots to visualize these associations are available in Additional file 1: Figure S2.

Discussion

In this prospective, longitudinal cohort study of 196 ARDS survivors, participant sociodemographic characteristics were not associated with missed assessments at either the initial 3-month visit or subsequent visits at 6-, 12-, and 24-months. ADLs at hospital discharge was associated with higher odds of missed assessments at the initial 3-month follow-up visit. At subsequent visits, post-discharge physical and mental health status were not associated with missed assessments. Instead, baseline (prior to hospitalization) IADLs along with missing assessments at preceding visit were associated with higher odds of missed assessments. Conversely, alcohol abuse and indicators of poor baseline physical health along with completing the preceding visit entirely at the research clinic (vs. other location or mode e.g. home, phone) were independently associated with lower odds of missed assessments at 6-, 12-, and 24-months.

To our knowledge, the present study is one of the first to evaluate factors associated with missed assessments within follow-up research visits of ARDS survivors. In our study, no sociodemographic characteristics were associated with missed assessments during follow-up visits. In contrast, studies of cohort attrition have found associations of loss to follow-up with sex, race, and economic status [5, 47,48,49]. After hospital discharge, health status measures, evaluated via 17 variables in this analysis, were not associated with missed assessments in subsequent visits. In studies of cohort attrition, researchers have found that psychiatric comorbidity was associated with increased odds of loss to follow-up [5, 6, 8]. Our dissimilar findings may be due to the different patient populations studied in these attrition studies or it may be that factors associated with attrition are truly different from factors associated with missing data in those who do attend visits. The latter hypothesis, if correct, highlights that our results complement findings from attrition studies, and that both must be considered to design effective strategies to mitigate missing data.

In the present study, indicators of poor pre-ARDS baseline health (i.e., alcohol abuse, inability to walk for 5 min, and unemployed due to health reason) were independently associated with lower odds of missed assessments. Conversely, dependencies in physical functioning (i.e. ADL and IADL) were associated with higher odds of missed assessments at both the initial visit and at subsequent visits. It is important to note the opposite direction of associations of baseline pre-hospital physical functioning (IADLs) versus other baseline indicators of health with missing assessments. This finding may reflect participants having greater availability (e.g. not working) to participate in research studies, but if their health limitations are severe enough, manifesting as dependencies in IADLs, then they face difficulty in completing the entire battery of assessments during each follow-up research visit. Similar to our findings, a study of burn injury patients, demonstrated higher odds of attrition for those with no pre-existing physical disability [4]. For participants who may have difficulty completing an entire battery of assessments, researchers may choose to prioritize to assess more important outcomes (e.g. primary outcome) ahead of secondary outcomes and to spread out the participants testing over more than one assessment to shorten the duration of each assessment. Notably, in our study, missingness was higher in performance-based measures (i.e. requiring in-person assessments – e.g. 6 min walk test) versus patient-reported outcomes (i.e., surveys that are often simpler and can be done by phone – e.g. EQ-5D). Feasibility of the proposed assessments is one of many issues that researchers should consider in designing their follow-up studies.

This study has a number of strengths, including low levels of participant attrition via extensive use of participant retention strategies as described in the Methods section and extensive collection of baseline demographic information, comorbidity and health status data, along with detailed longitudinal assessments of physical and mental health status for these analyses. Our team was well-trained and adhered to the study’s detailed retention protocol. The longitudinal design allowed us to examine changes in associations over time, with the finding that associations remained relatively constant over time. Despite these strengths, there are potential limitations. First, baseline health, functional, and quality of life status prior to hospital admission were obtained from retrospective interviews, which may introduce recall bias. The inability to obtain prospective baseline status is an inherent challenge in studies involving ARDS patients given the emergent and unpredictable nature of ARDS onset. Second, the cohort retention efforts employed in this study may differ from other studies, affecting generalizability of the associations observed in the factors we evaluated. We did not evaluate the association of study team factors with missing assessments in this study, though factors such as limitations in staff availability and training may have been contributed to missing assessments. However, missing assessments unrelated to participant factors (e.g. staff availability) were excluded from consideration as a “missed” assessment. Finally, the results may not be generalizable to other patient populations as the study involved patients with ARDS (n = 196 at first follow-up) from four urban hospitals in one city.

Conclusions

In conclusion, within the setting of a prospective multisite longitudinal cohort study, we evaluated > 30 variables for associations with missed assessments during follow-up research visits. Baseline sociodemographic characteristics and post-discharge physical and mental health status were not associated with missed assessments during follow-up visits. However, physical functioning prior to study enrollment and at hospital discharge, indicators of poor baseline health and alcohol abuse, and participant history of research visits were each independently associated with missing assessments during follow-up research visits. Investigators planning longitudinal follow-up studies should collect information on baseline health status, physical functioning at hospital discharge, and status of preceding visits to identify participants at risk of missing assessments. This relatively small number of easy to collect data offer invaluable insights for tailoring retention and visit completion efforts to mitigate missing assessments at each follow-up visit.

References

Turnbull AE, Rabiee A, Davis WE, et al. Outcome measurement in ICU survivorship research from 1970-2013: a scoping review of 425 publications. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(7):1267–77. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000001651.

Wood AM, White IR, Thompson SG. Are missing outcome data adequately handled? A review of published randomized controlled trials in major medical journals. Clin Trials Lond Engl. 2004;1(4):368–76.

Fewtrell MS, Kennedy K, Singhal A, et al. How much loss to follow-up is acceptable in long-term randomised trials and prospective studies? Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(6):458–61. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2007.127316.

Berk RA. An introduction to sample selection bias in sociological data. Am Sociol Rev. 1983;48(Journal Article):386–98.

Holavanahalli RK, Lezotte DC, Hayes MP, et al. Profile of patients lost to follow-up in the burn injury rehabilitation model systems’ longitudinal database. J Burn Care Res Off Publ Am Burn Assoc. 2006;27(5):703–12. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.BCR.0000238085.87863.81.

O’Donnell ML, Creamer M, Pattison P, Atkin C. Psychiatric morbidity following injury. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(3):507–14.

Ehlers A, Mayou RA, Bryant B. Psychological predictors of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder after motor vehicle accidents. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107(3):508.

Mason S, Wardrope J, Turpin G, Rowlands A. The psychological burden of injury: an 18 month prospective cohort study. Emerg Med J EMJ. 2002;19(5):400–4.

Krellman JW, Kolakowsky-Hayner SA, Spielman L, et al. Predictors of follow-up completeness in longitudinal research on traumatic brain injury: findings from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research traumatic brain injury model systems program. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(4):633–41.

Hofhuis JG, Spronk PE, van Stel HF, Schrijvers GJ, Rommes JH, Bakker J. The impact of critical illness on perceived health-related quality of life during ICU treatment, hospital stay, and after hospital discharge: a long-term follow-up study. Chest J. 2008;133(2):377–85.

Wehler M, Geise A, Hadzionerovic D, et al. Health-related quality of life of patients with multiple organ dysfunction: individual changes and comparison with normative population. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4):1094–101. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CCM.0000059642.97686.8B.

Gifford JM, Husain N, Dinglas VD, Colantuoni E, Needham DM. Baseline quality of life before intensive care: a comparison of patient versus proxy responses. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(3):855–60. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cd10c7.

Dowdy DW, Eid MP, Dennison CR, et al. Quality of life after acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(8):1115–24.

Davydow DS, Gifford JM, Desai SV, Bienvenu OJ, Needham DM. Depression in general intensive care unit survivors: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(5):796–809.

Davydow DS, Desai SV, Needham DM, Bienvenu OJ. Psychiatric morbidity in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(4):512–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e31816aa0dd.

Wade D, Hardy R, Howell D, Mythen M. Identifying clinical and acute psychological risk factors for PTSD after critical care: a systematic review. Minerva Anestesiol. 2013;79(8):944–63.

Parker AM, Sricharoenchai T, Raparla S, Schneck KW, Bienvenu OJ, Needham DM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: a metaanalysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(5):1121–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000000882.

Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1306–16.

Needham DM, Dennison CR, Dowdy DW, et al. Study protocol: The Improving Care of Acute Lung Injury Patients (ICAP) study. Crit Care Lond Engl. 2006;10(1):R9.

Needham DM, Dinglas VD, Bienvenu OJ, et al. One year outcomes in patients with acute lung injury randomised to initial trophic or full enteral feeding: prospective follow-up of EDEN randomised trial. BMJ. 2013;346:f1532. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f1532.

Needham DM, Dinglas VD, Morris PE, et al. Physical and cognitive performance of patients with acute lung injury 1 year after initial trophic versus full enteral feeding. EDEN trial follow-up. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(5):567–76. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201304-0651OC.

Dinglas VD, Hopkins RO, Wozniak AW, et al. One-year outcomes of rosuvastatin versus placebo in sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: prospective follow-up of SAILS randomised trial. Thorax. 2016; https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-208017.

Jackson JC, Girard TD, Gordon SM, et al. Long-term cognitive and psychological outcomes in the awakening and breathing controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(2):183.

Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, et al. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and functional disability in survivors of critical illness in the BRAIN-ICU study: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(5):369–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70051-7.

Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, et al. The American-European consensus conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149(3 Pt 1):818–24. https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706.

Ranieri V, Rubenfeld G, Thompson B, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. J Am Med Assoc. 2012;307(23):2526–33. (Journal Article)

Robinson KA, Dennison CR, Wayman DM, Pronovost PJ, Needham DM. Systematic review identifies number of strategies important for retaining study participants. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(8):757.e1–757.e19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.11.023.

Tansey CM, Matté AL, Needham D, Herridge MS. Review of retention strategies in longitudinal studies and application to follow-up of ICU survivors. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(12):2051–7.

Coday M, Boutin-Foster C, Sher TG, et al. Strategies for retaining study participants in behavioral intervention trials: retention experiences of the nih behavior change consortium. Ann Behav Med. 2005;29(2):55–65. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm2902s_9.

Jr H, White E. Retaining and tracking cohort study members. Epidemiol Rev. 1998;20(1):57–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017972.

Katz S. Assessing self-maintenance: activities of daily living, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1983;31(12):721–7.

Ventry IM, Weinstein BE. Identification of elderly people with hearing problems. ASHA. 1983;25(7):37–42.

The EuroQol Group. EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208.

Ware JE. How to score version 2 of the SF-12 health Survey : with a supplement documenting version 1. Lincoln: Quality Metric; 2002.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70.

Bienvenu OJ, Williams JB, Yang A, Hopkins RO, Needham DM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of acute lung injury. Chest. 2013;144(1):24–31. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.12-0908.

Enright PL. The six-minute walk test. Respir Care. 2003;48(8):783–5.

Wadsworth CT, Krishnan R, Sear M, Harrold J, Nielsen DH. Intrarater reliability of manual muscle testing and hand-held dynametric muscle testing. Phys Ther. 1987;67(9):1342–7.

Schmidt RT, Toews JV. Grip strength as measured by the Jamar dynamometer. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1970;51(6):321–7.

Marini JJ, Smith TC, Lamb V. Estimation of inspiratory muscle strength in mechanically ventilated patients: the measurement of maximal inspiratory pressure. J Crit Care. 1986;1(1):32–8.

Brandt J, Spencer M, Folstein M. The telephone interview for cognitive status. Cogn Behav Neurol. 1988;1(2):111–8.

Wallace KL, Middleton S, Cook IJ. Development and validation of a self-report symptom inventory to assess the severity of oral-pharyngeal dysphagia. Gastroenterology. 2000;118(4):678–87.

Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(11):1245–51.

Groll DL, To T, Bombardier C, Wright JG. The development of a comorbidity index with physical function as the outcome. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(6):595–602.

McCullagh P, Nelder J. Generalized linear models. In: Monographs on Statistics and Applied Probability. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 1989. p. 160.

Hoffmann JP. Generalized Linear Models: An Applied Approach. Boston: Pearson; 2004.

DeVita DA, White MC, Zhao X, Kaidarova Z, Murphy EL. Determinants of subject visit participation in a prospective cohort study of HTLV infection. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-9-19.

Park M, Yamazaki Y, Yonekura Y, et al. Predicting complete loss to follow-up after a health-education program: number of absences and face-to-face contact with a researcher. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:145. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-145.

Bambs CE, Kip KE, Mulukutla SR, et al. Sociodemographic, clinical, and psychological factors associated with attrition in a prospective study of cardiovascular prevention: the heart strategies concentrating on risk evaluation study. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23(6):328–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.02.007.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all patients who participated in the study and the dedicated research staff who assisted with data collection and management for the study, including Dr. Nardos Belayneh, Ms. Rachel Bell, Ms. Kim Pitner, Dr. Abdulla Damluji, Ms. Carinda Feild, Ms. Lisa Aronson Friedman, Ms.Thelma Harrington, Dr. Praveen Kondreddi, Mr. Robert Lord, Ms. Frances Magliacane, Ms. Jennifer McGrain, Ms. Stacey Murray, Dr. Kim Nguyen, Dr. Susanne Prassl, Ms. Arabela Sampaio, Ms. Kristin Sepulveda, Dr. Shabana Shahid, Dr. Faisal Siddiqi, and Ms. Michelle Silas.

Funding

This project was supported through a grant from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI R24HL111895). The ICAP study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (P050HL73994, R01HL088045, and K24HL088551), along with the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR) (UL1 TR 000424–06). The funding bodies had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset for the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EC, AWW, DMN, and VDD contributed to the conception and/or design of this study. KAS, PAM-T, CD-H, DMN and VDD contributed to the acquisition of data. All authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. SEH, AWW, and VDD drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed, read and approved the final version to be submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained from the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board, University of Maryland, Baltimore Institutional Review Board and VA Research & Development Committee. Written consent was obtained for each participant.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

“Supplementary Material for Factors Associated with Missed Assessments in a 2-year Longitudinal Study of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Survivors”, This file contains the following: Analysis – Additional explanation of binomial logistic regression, Table S1. Number (percentage) of missed assessments over 3-, 6-, 12, and 24-month follow-up after ARDS, Table S2. Results of Regression Diagnostics, Figure S1. Mean logit of proportion of missed assessment for variables included in the 3-month multivariable model, Figure S2. Mean logit of proportion of missed assessment for variables included in the 6–12-24-month multivariable model. (PDF 297 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Heins, S.E., Wozniak, A.W., Colantuoni, E. et al. Factors associated with missed assessments in a 2-year longitudinal study of acute respiratory distress syndrome survivors. BMC Med Res Methodol 18, 55 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0508-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0508-8