Abstract

Background

Our understanding of post-ICU recovery is influenced by which patients are selected to study and treat. Many studies currently list an ICU length of stay of at least 24, 48, or 72 h as an inclusion criterion. This may be driven by established evidence that prolonged time in an ICU bed and prolonged ventilation can complicate post-ICU rehabilitation. However, recovery after short ICU stays still needs to be explored.

Methods

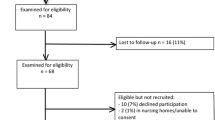

This is a secondary analysis from the tracking outcomes post-intensive care (TOPIC) study. One hundred and thirty-two participants were assessed 6-months post-ICU discharge using standardised and validated self-report tools for physical function, cognitive function, anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (with clinically significant impairment on any tool being considered a complicated recovery). Routinely collected data relating to the ICU stay were retrospectively accessed, including length of stay and duration of mechanical ventilation. Patients with short ICU stays were intentionally included, with 77 (58%) participants having an ICU length of stay < 72 h.

Results

Of 132 participants, 40 (30%) had at least one identified post-ICU impairment 6 months after leaving ICU, 22 (17%) of whom had an ICU length of stay < 72 h.

Conclusion

Many patients with an ICU length of stay < 72 h are reporting post-ICU impairment 6 months after leaving ICU. This is a population often excluded from studies and interventions. Future research should further explore post-ICU impairment among shorter stays.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

With most patients now surviving ICU, academic and clinical focus has shifted to quality of survival. Up to 80% of patients discharged from ICU experience ongoing cognitive, psychological, or physical impairments, known as post-intensive care syndrome (PICS), which can persist for years at great cost to patients, families, and society [1]. Despite over a decade of research, the aetiology and best prevention/treatment strategies for PICS remains elusive and an ongoing priority [1]. Optimising recovery is an ethical and economic imperative.

Two key challenges need to be overcome to support evidence-based prevention and treatment strategies [2] to improve outcomes. The first is identification of the characteristics of ICU patients who develop PICS, including modifiable and unmodifiable risk factors [3]. The second is to elucidate the ways which those factors complicate recovery.

Because PICS is a complex problem experienced by a heterogeneous population, our understanding is inherently shaped by which patients we choose to study and treat [4]. A recent systematic review identified that in nearly half of pertinent studies an ICU length of stay (LoS) of at least 24, 48, or 72 h was inclusion criteria [3]. The implication is that the risk of PICS among short ICU stays is low enough that study or intervention is unnecessary. This may be driven by established evidence that prolonged time in an ICU bed and prolonged ventilation can complicate post-ICU rehabilitation [5].

However, while patients with prolonged ICU stays may be at elevated risk of PICS, the recovery after short ICU stays still needs to be explored unless evidence confirms there is no burden of PICS among them.

This manuscript is grounded in a secondary analysis from the tracking outcomes post-intensive care (TOPIC) study [6], a prospective observational study that recruited participants discharged from participating ICUs. One hundred and thirty-two participants were assessed 6-month post-ICU discharge for impairments using standardised and validated self-report tools. These included measures of Physical Impairment (EQ-5D-5L [7]), Cognitive Impairment (PROMIS-Cog-8a [8]), Anxiety and Depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS [9])) and PTSD (Trauma Screening Questionnaire (TSQ [10])).

Results

TOPIC included 132 patients. Thirty percent (n = 40) had at least one identified post-ICU impairment 6 months after leaving ICU, including 29% (n = 22/77) with LoS < 72 h and 33% (n = 18/55) with LoS ≥ 72h.

Figure 1 shows the distribution of participants experiencing impairments by their ICU length of stay and ventilation duration, respectively.

Impairments were reported across the ICU duration of stay spectrum. The prevalence of physical, cognitive, and psychological impairments among the < 72 h LoS group was 14% (n = 11/77), 13% (n = 10/77), and 21% (n = 16/77), respectively. The ≥ 72 h LoS group had a comparable prevalence of physical impairment, with 19% (n = 10/54), a much lower cognitive impairment prevalence of 4% (n = 2/54) and slightly higher prevalence of psychological impairment, with 28% (n = 15/54).

Discussion

Many patients discharged from ICUs after a short length of stay, and brief periods of mechanical ventilation go on to experience post-ICU impairments.

This population represents a substantial burden of morbidity. Over 188,000 patients were discharged from Australian ICUs in 2023, with a median ICU length of stay of 1.8 days [11], meaning over 50% were in ICU for < 48 h, a threshold below which many post-ICU studies and services are currently not recruiting. Our data suggest as many as 29,000 such patients may develop impairments in Australia each year and are currently being excluded from many studies and follow-up services.

These findings do not suggest that a long length of stay or ventilation duration is not an important risk factor for PICS, and it remains likely that prolonged ICU stays and associated factors such as patient characteristics, severity of illness, ICU delirium, and loss of muscle mass are important factors for clinicians to consider and address [1, 5], but this cannot be allowed to overshadow the morbidity faced by patients with shorter ICU stays.

The factors contributing to PICS among shorter ICU stays are likely to be different. These patients receive a lower dose exposure to in-ICU factors such as immobilisation and ICU delirium. Pre-ICU factors around how the illness/injury developed, within-ICU factors that are not time-sensitive (such as medications and procedures administered) and post-ICU factors such as external support systems are possible contributors to post-ICU impairment in this group. For patients that develop PTSD, it is important to consider that the index traumatic experience can have a very short duration (for example, a motor vehicle collision may only last a few seconds). As such, precipitants to PTSD may not show a temporal dose–response. Further, it is important to consider that such processes would not be limited to short ICU stay patients and may be represented across the ICU length of stay spectrum.

The prevalence of PICS among patients with a short ICU length of stay and ventilation duration in our study was considerable and represents a potential burden of morbidity that may be currently understudied and undertreated. It is therefore an urgent ethical and economic imperative that patients discharged after shorter ventilation and ICU admission times be included in both future research and treatment efforts.

Availability of data and materials

Data are provided within the manuscript or Additional files 1.

References

Voiriot G, Oualha M, Pierre A, Salmon-Gandonnière C, Gaudet A, Jouan Y, et al. Chronic critical illness and post-intensive care syndrome: from pathophysiology to clinical challenges. Ann Intensive Care. 2022;12(1):58.

Inoue S, Hatakeyama J, Kondo Y, Hifumi T, Sakuramoto H, Kawasaki T, et al. Post-intensive care syndrome: its pathophysiology, prevention, and future directions. Acute Med Surg. 2019;6(3):233–46.

Lee M, Kang J, Jeong YJ. Risk factors for post–intensive care syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust Crit Care. 2020;33(3):287–94.

Flaws D, Patterson S, Fraser J, Tronstad O, Scott JG. Reconceptualizing post-intensive care syndrome: do we need to unpick our PICS? Nurs Crit Care. 2021;26(2):67–9.

Girard TD, Pandharipande PP. Early mobilisation during critical illness: good for the body and brain. Lancet Respirat Med 2023.

Flaws DF, Barnett A, Fraser J, Latu J, Ramanan M, Tabah A, et al. A protocol for tracking outcomes post intensive care. Nurs Crit Care. 2022;27(3):341–7.

Feng Y-S, Kohlmann T, Janssen MF, Buchholz I. Psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2021;30:647–73.

Fieo R, Ocepek-Welikson K, Kleinman M, Eimicke JP, Crane PK, Celia D, et al. Measurement equivalence of the patient reported outcomes measurement information System®(PROMIS®) applied cognition—general concerns, short forms in ethnically diverse groups. Psychol Test Assessment Model. 2016.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70.

Walters JT, Bisson JI, Shepherd JP. Predicting post-traumatic stress disorder: validation of the Trauma Screening Questionnaire in victims of assault. Psychol Med. 2007;37(1):143–50.

ANZICS publicreports.anzics.com.au.

Funding

This project was made possible by a clinician research fellowship awarded to DF by Metro North Hospital and Health Service, and further supported by a Collaborative Research Grant awarded to DF by Metro North Hospital and Health Service in collaboration with Queensland University of Technology, a project grant awarded to DF by the Jamieson Trauma Institute, and a Fellowship top-up awarded to DF by University of Queensland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to methodological design, interim analysis, results interpretation, planning and review of the manuscript. DF also wrote the main manuscript and prepared figure 1.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained from an Authorised Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval number: HREC/2020/QRBW/62033).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Data used in analysis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Flaws, D., Fraser, J.F., Laupland, K. et al. Time in ICU and post-intensive care syndrome: how long is long enough?. Crit Care 28, 34 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-024-04812-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-024-04812-7