Abstract

Background

It is reported that an increase in food diversity would lower the risk of cardiac–cerebral vascular diseases.

Methods

A new index was introduced to develop a Chinese healthy food diversity (HFD) index, exploring the association with metabolic syndrome (MetS) and its components among Chinese adults. Two sets of data were used. The primary data were from a cross-sectional survey conducted in 2016 called the Chinese Urban Adults Diet and Health Study (CUADHS); the verification data were from the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS) of 2009. The Chinese HFD index was developed according to the Chinese Dietary Guideline, with food consumption information from 24-h dietary recalls. The association between the index and MetS and its components was explored in logistic regression models.

Results

Among 1520 participants in the CUADHS, the crude prevalence of MetS was 36.4%, which was 29.0% after the standardisation of age and gender by the 2010 Chinese national census. In the CUADHS, the HFD index ranged from 0.04 to 0.63. The value of the index among participants who are male, young, poorly educated, drinking or smoking, and with high energy intakes was significantly lower than that of their counterparts. In the verification dataset of the CHNS, there were 2398 participants, and the distribution of different genders and age groups was more balanced. The crude prevalence of MetS in the CHNS was 27.3% and the standardised prevalence was 19.5%. The Chinese HFD index ranged from 0.02 to 0.62. In the CUADHS, the Chinese HFD index was not significantly associated with MetS in covariate-adjusted models or with its components. In the CHNS, the Chinese HFD index had a significantly negative correlation with MetS and its components (i.e., elevated fasting glucose and elevated waist circumference) in covariate-adjusted models.

Conclusions

Increased food diversity may decrease the risk of MetS, which is important in dietary interventions of cardiac–cerebral vascular disease. This underscores the necessity of continued investigation into the role of HFD in the prevention of MetS and provides an integral framework for ongoing research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a clustering of risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and type 2 diabetes and has been a public health challenge globally [1,2,3]. People diagnosed with MetS have a five-time higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes and are twice as likely to develop CVD within the next 5–10 years [4, 5]. It has been reported that the occurrence of MetS increases total mortality by 1.5 times and cardiovascular death by 2.5 times [5, 6]. The prevalence of MetS is striking in both developed and developing countries. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) of the United States showed that the prevalence of MetS among adults increased from 25.3% in 1988–1994 to 34.2% in 2007–2012. The Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) from 2008 to 2013 found a stable prevalence of 28.9%. In China’s most recent national survey in 2009, a prevalence of 21.3% was reported [6,7,8]. It should be noticed that the prevalence of MetS in different areas of China was largely altered, ranging from 20 to 45% [9,10,11].

Environmental factors, including diet, exercise, stress, and certain addictions (tobacco or alcohol), as well as genetic factors are crucial in the development of MetS [12,13,14]. Lifestyle modification, such as dietary intervention, is recommended to manage MetS. Studies have reported that some dietary components influence MetS directly, as either protective factors or risk factors [15,16,17,18,19]. There are many researches focusing on the association between dietary pattern or kinds of indices evaluating dietary quality and MetS. However, it is difficult for most people to develop and sustain healthful dietary patterns with individual knowledge and self-control, particularly given that transformations in diet environments have expanded access to all kinds of food [12, 20,21,22]. The increasing dietary variety comes with benefits and challenges. On the one hand, it avoids malnutrition; on the other hand, it may result in overweight and obesity [23,24,25].

Dietary guidelines recommended by government institutions or national nutrition associations provide guidance to the public and serve as referential files when designing dietary and nutritional interventions. Researchers in Germany and the US developed and validated a healthy food diversity (HFD) index based on actual food guidelines and explored the correlation between HFD and body adiposity and MetS [26,27,28]. The US researchers found that the HFD index values were inversely associated with indicators of body adiposity; the odds of obesity and android-to-gynoid ratio > 1 are lower among those with a higher US HFD index [26]. In a randomised-controlled clinical weight-loss trial, participants with a higher US HFD index had greater weight loss and waist circumference (WC) reduction [29]. Besides, the US HFD index was inversely associated with components of MetS, including elevated WC and low HDL cholesterol [27].

The latest version of the dietary guidelines in China was released in 2016, and up to now there is no study introducing the Chinese HFD index. It is necessary and meaningful to develop and evaluate an index considering food type, quality, and consumption amounts simultaneously, and to explore its association with health conditions in Chinese adults in order to guide dietary interventions.

In this study, we developed the Chinese HFD index based on the Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents and then examined its associations with MetS and its components in urban adults.

Methods

Study design and participants

There were two sets of data in the analysis. The primary data were from a cross-sectional survey designed and conducted by our team, the Chinese Urban Adults Diet and Health Study (CUADHS), conducted from March to July 2016, in which a multi-stage sampling method was utilised to recruit adult subjects. Firstly, eight cities were selected based on geographical location and economic status, including two first-tier cities with higher economic performance. Secondly, two communities from each first-tier city and one community from each non-first-tier city were chosen by convenience sampling. In the last step, subjects were recruited by age groups, with at least 60 people from the age group of 18–44 years, 60 from 45 to 64 years, and 50 from over 65 years in each community. The study recruited 1806 subjects, and those with a physical disability, mental illness, or memory problems and women who were pregnant were excluded from analysis. In the end, a total of 1520 subjects were considered eligible for this study. We obtained a formal written agreement from each participant.

The verification data were from the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS) of 2009. The CHNS is an international collaborative project between the National Institute for Nutrition and Food Safety of the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. As a longitudinal, household-based survey, it was conducted in 1989, 1991, 1993, 1997, 2000, 2004, 2006, 2009, and 2011 in sequence. Only the survey conducted in 2009 contained information about blood biochemical examination. Details are provided elsewhere [30]. Questionnaires and blood biochemical tests were used to collect information of adults (except pregnant women) living in urban areas (i.e., residence in city and town or county capital city). In this study, we analysed 2398 individuals from the CHNS who met our inclusion criteria described in the data collection section.

Data collection

In the CUADHS, the interviewer-administered questionnaires contained questions about socio-demographic characteristics, lifestyles, disease history, health literacy, dietary intakes, and physical examination. Anthropometry measurement and blood tests were also conducted. The food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) and 24-h dietary recall for 1 day were used in this study to collect dietary intake information. The FFQ was a semi-quantitative questionnaire, in which 41 groups of food were asked about regarding the frequency and amount of consumption within the past month. Intakes of different kinds of alcohol and beverages were included. One-time 24-h dietary recall was used to obtain the data on food intakes, and then nutrient intakes were calculated based on it. About 1/8 (205 adults) of the subjects were invited to complete the 24-h dietary recall for 3 days to evaluate the representativeness of one-time 24-h dietary recall. Energy and nutrient intakes were calculated and analysed based on the Chinese Food Composition Tables (CFCT) of 2004 and 2009 (CFCT, National Institute of Nutrition and Food Safety, China CDC), the Standard Tables of Food Composition in Japan (2010), and the nutrient composition table on the food packaging. Training of the interviewers and a pilot investigation were completed prior to data collection.

Questionnaire information and blood biochemical indices of the CHNS 2009 were downloaded from the official website of the CHNS, and information was gathered about socio-demographic characteristics, lifestyles, disease history, 24-h dietary recalls for 3 days, consumption of household food inventory, energy and macronutrient intakes, anthropometry information, and blood biochemical indices labelled by specimen collection and processing by the China–Japan Friendship Hospital (CJFH).

Assessment of diet factors and development of the Chinese HFD index

For the CUADHS, we calculated energy and nutrient intakes based on CFCT, Standard Tables of Food Composition in Japan [31], and ingredient lists of common supplements. Then we computed the absorbed amount of special micronutrients by bioavailability adjustment, the detailed processing procedure of which is described elsewhere [32]. We referred to the FAO protocol [33] to calculate the probabilities of nutrient adequacy (PA) of some nutrients based on Chinese Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) 2013 edition, which included definitions and specified values for estimated average requirements (EAR) and recommended nutrient intakes (RNI). The equation was PA = Probnorm [(estimated intakes-EAR)/CV] for most nutrients except iron; the CV was set to 10% of EAR for all nutrients except vitamin A (20%), niacin (15%), and zinc (25%).

For iron, since its distribution was not normal, we used the eq. PA = estimated participant’s intake/RNI. PA was defined as the ratio of a certain nutrient intake to its recommended allowance, and when intakes of a certain nutrient exceeded requirement, the value should be capped at 1, indicating 100% adequacy. We calculated the PA of protein, carbohydrates, vitamin A, niacin, vitamin B6, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, vitamin B12, vitamin C, folate, calcium, iron, and zinc. We then calculated the mean probability of adequacy (MPA) of micronutrients by applying equal weight to every individual micronutrient.

We evaluated the representativeness of one-time 24-h dietary recall in the CUADHS, and the results are showed in Additional file 1: Table S1. There were no significant differences in energy and macronutrient intakes between one-time 24-h dietary recall and three-day 24-h dietary recall. We decided that one-time 24-h dietary recall was able to represent the results of 24-h dietary recall for 3 days, which was similar to other studies [34,35,36].

In the CHNS the food intakes of every participant were the summation of two parts. Firstly, daily average food intake was calculated from three-day 24-h dietary recalls. Secondly, for food consumed at home, the daily amount of each ingredient from the household food inventory consumed by each individual was estimated based on his/her respective proportion of energy intake in the whole family.

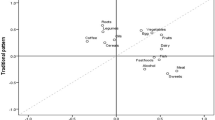

For the two studies, all of the food items were divided into 15 groups according to the Dietary Guideline and Balance Diet Pagoda for Chinese Residents (as showed in Table 1), and, subsequently, the consumption of each food group was calculated, respectively. Though there were only 12 food groups in the Balance Diet Pagoda, in the detailed Dietary Guidelines there were precise recommended daily/weekly intakes of 15 food groups, in which cereals, tubers, and beans were divided into three groups: whole grains and legumes, tubers, and refined grains. Soya and nuts were divided into two groups: soya products and nuts and seeds [37]. According to similar research [28, 38], weight based on the recommended proportions of each food group at the 2000-kcal level in the Dietary Guideline and Balance Diet Pagoda for Chinese Residents was selected to build the Chinese HFD index (Table 1). There was no precise definition for dark green and yellow or orange vegetables in the recommendation, so we redefined them as vegetables rich in vitamin A (content of vitamin A ≥ 150 RAE/100 g; RAE = retinol equivalent) or vitamin C (content of vitamin C ≥ 50 mg/100 g). The Chinese HFD index values were calculated using the following algorithm:

Chinese HFD index=\( \left(1-\sum {S}_i^2\right)\times \mathrm{hv} \),

in which \( {S}_i=\frac{\ Amount\ of\ recommended\ food\ group\kern0.5em i\ by\ weight\ }{\ Amount\ of\ 15\ food\ groups\ by\ weight} \),

hv = ∑ hfi × Si, hfi = Broad food share × share of food group,

where Si is the quantitative share of a single food group; hv is the health value; and hfi is health factors.

Theoretically, the range of the Chinese HFD index is between 0 (i.e., a diet with a single food group) and nearly 1 (i.e., a more balanced diet). In fact, the maximum hv that can be achieved according to the recommendation at the 2000-kcal level is 0.187, and the Chinese HFD index was calibrated by dividing hv by its maximum. Then, the Chinese HFD index values and energy intakes were equally divided into four groups (Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4).

Assessment of non-dietary factors

We categorised age groups as 18~ 44.9 years old, 45~ 54.9 years old, 55~ 64.9 years old, and ≥ 65 years old. Smoking status was classified as never smoked, former smoker, and current smoker. Drinking behaviours were defined as not drinking and drinking now. Physical activity (PA) levels calculated from a PA questionnaire were trisected from the smallest to the highest and marked as T1, T2, and T3, which were expressed as metabolic equivalents (MET)/d; subjects who only reported sedentary behaviours were classified as a separate group. Educational background was classified as illiterate, middle school or lower, high school or professional training, undergraduate, and postgraduate student or higher. Body mass index (BMI) was defined as weight (in kilograms) divided by the squared height (in metres). Consistent with the WHO criteria, obesity, overweight, normal, and underweight were defined as BMI ≥28 kg/m2, BMI ≥24 kg/m2 and < 28 kg/m2, BMI ≥18.5 kg/m2 and < 24 kg/m2, and BMI<18.5 kg/m2, respectively [39].

Diagnostic criteria of MetS

The definition of MetS was consistent with the most recent Joint Interim Statement (JIS) by adopting the Asian criteria for WC recommended by the International Diabetes Federation. Indicators of MetS are shown in Table 2, and subjects were diagnosed as patients if they had at least three of the indicators [5]. The methods of measuring anthropometry indicators and blood biochemical indices are presented in Additional file 2: Table S2.

Statistical analysis

Normality was examined before the related analysis. Values were presented as mean ± standard deviation (\( \overline{x}\pm SD \)) for continuous variables or as number (percentage) for categorical variables. Student t tests or one-way ANOVA were performed to compare means between different groups. Chi-square tests or trend Chi-square tests were performed to compare the distribution of categorical variables. Kendall’s tau-b correlation was tested between PA/MPA and the Chinese HFD index, with energy intake as a covariate. Binominal unconditional logistic regression models were used to estimate the effects of factors on MetS and the regression coefficients (ORs), and their 95% confidence interval (CI) was obtained. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistic Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P values lower than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics and the prevalence of MetS and its components

There were 1520 adults analysed in the CUADHS, of which 527 were male. Those who were 18~ 44.9 years old and older than 65 years accounted for about 1/3 of the total, respectively. The educational attainment of about 70% participants was high school or lower. About half of the participants never smoked and were non-drinking now. The prevalence of overweight and obesity was 35.4% and 11.0%, respectively. The detailed distribution of demographic characteristics is showed in Table 3.

Table 3 also shows that in the CUADHS the prevalence of MetS was 36.4%, which was 29.0% after standardisation of age and gender by the 2010 Chinese national census. Significant differences in the prevalence of MetS were found between different groups of gender, age, education, smoking behaviour, BMI, and HFD index. The prevalence of MetS and its five components was significantly higher in participants who are male, older, poorly educated, a former or current smoker, and overweight or obese.

In the verification data of the CHNS, 2398 participants were analysed, and the distribution of gender (47.9% male) and age groups (30.9%, 25.4%, 20.7%, and 23.0%, respectively) was more balanced than that of the CUADHS. For the educational attainment, more than 85% of the participants were high school or lower. About 70% of the participants never smoked and were non-drinking now. The prevalence of overweight and obesity was 32.7% and 11.1%, respectively. Detailed information is shown in Table 4.

The crude prevalence of MetS in the CHNS was 27.3%, and the standardised prevalence was 19.5%. The prevalence of MetS was significantly higher in participants who are older, poorly educated, overweight or obese, and lack PA, while no similar trend was found in the five components of MetS.

Distribution of the Chinese HFD index and its correlations with nutrients

In the CUADHS, the Chinese HFD index ranged from 0.04 to 0.63. The values of the index were significantly lower in participants who are male, young, poorly educated, drinking or smoking now, and with high energy intakes (Table 5).

To validate the Chinese HFD index, correlations between the Chinese HFD index and PA of nutrients were analysed, and the results are showed in Table 6. The Chinese HFD index was positively correlated with PA of carbohydrates, vitamin B2, niacin, vitamin B6, folate, vitamin A, vitamin C, and MPA of micronutrients after adjusting for energy.

In the verification study, the Chinese HFD index ranged from 0.02 to 0.62, as showed in Table 5. Participants who were male, young, poorly educated, drinking or smoking now, obese, and with the highest energy intakes had a significantly lower Chinese HFD index.

Regression analysis of the Chinese HFD index and MetS and its components

As shown in Table 7, in the CUADHS the Chinese HFD index was not significantly associated with MetS in covariate-adjusted models or its components. Only in an unadjusted model was the Chinese HFD index positively correlated with elevated fasting glucose and reduced HDL.

In the verification data of the CHNS, the results were different, as shown in Table 8. The Chinese HFD index was significantly negatively correlated with MetS and its components of elevated fasting glucose and elevated WC in covariate-adjusted models. It indicated that a higher Chinese HFD index decreased the risk of MetS.

Discussion

This study was conducted to analyse the associations between MetS and food diversity in Chinese urban adults, and the analysis was repeated in a representative sample for validation. In the two studies, the prevalence of MetS was within the range of contemporaneous researches. In this study, a multi-dimensional food diversity index in consideration of dietary quality and proportionality was applied to evaluate the associations between food diversity and MetS and its components in Chinese adults. The Chinese HFD index was positively correlated with carbohydrates and micronutrients, meaning that if one had a higher HFD index, he/she was more likely to have adequate nutrient intakes. In comparison, the correlations between the Chinese HFD index and PA of most nutrients were weaker than those of the German population (except vitamin A) and US population (except vitamin C), despite the fact that the two foreign studies neglected bioavailability adjustment of minerals [28, 38]. The Chinese HFD index could reflect dietary quality to some extent.

The mean and range of the Chinese HFD index of participants in the two studies were similar, and the trend by grouping factors was also similar. The Chinese HFD index values in the two studies were comparable with the studies conducted in the US and Germany [27,28,29, 38]. They were also the same as former studies in which the participants who are old, female, and with higher educational attainment were more likely to have a higher HFD index value [26, 27]. Considering that the CUADHS and the CHNS were two independent surveys, the comparable results indicated the feasibility and applicability of the methods in the Chinese population.

Currently, economic growth and globalisation have increased access to seasonal, animal-source, and processed foods, which may result in the intake of both high- and low-quality foods. Health effects of food variety or diversity are controversial; for example, some researches have showed that greater food variety resulted in increased food consumption and obesity [23, 40, 41], while others have indicated beneficial effects of food variety on weight control [42, 43]. However, the difference in definition of food variety between studies should be noticed. The Chinese HFD index was based on recommended food groups for adults to keep healthy, and it considered three aspects comprehensively: type, amount, and health value of consumed food. Participants with higher Chinese HFD index values showed better adherence to the Dietary Guideline and Balance Diet Pagoda for Chinese Residents, and our assumption was that the higher Chinese HFD index values would favourably influence MetS and its components.

In CUADHS data, we did not find that a higher Chinese HFD index influenced the risk of MetS and its components. In CHNS data, it is significant that the Chinese HFD index was negatively correlated with MetS and its components of elevated fasting glucose and elevated WC, suggesting favourable effects of food diversity on MetS and its components. The Chinese HFD index was negatively correlated with elevated WC, and it was similar with the results of articles exploring the influence of HFD on MetS or obesity [26, 27]. The protective effect of food diversity on weight control was proved in some studies [44,45,46], and it was supposed that diversified diets would provide adequate vitamins, minerals, and bioactive substances but moderate or restricted energy, leading to more balanced and healthier diets. In our research, we verified that those people with the lowest Chinese HFD index had the highest energy intakes.

There are researches exploring the correlations between food diversity and glucose homeostasis, suggesting that higher food diversity decreased the risk of diabetes or impaired glucose homeostasis [44, 47, 48]. The protection mechanism was partly attributed to its favourable effects on weight control, and further research was needed to explore the mechanism accurately.

Our research showed that the Chinese HFD index was negatively correlated with MetS and some of its components, indicating that the increase in food diversity would decrease the risk of MetS. Although we failed to find correlations between the Chinese HFD index and hypertension or dyslipidemia, results of other researches support the premises that higher food diversity lowers cardiovascular risk and an increase in food diversity is important in dietary interventions against chronic non-communicable diseases [47].

There were some limitations of our analysis that cannot be ignored. Firstly, we failed to incorporate family medical history or genetic factors into the analysis. Secondly, we applied one-day or three-day 24-h dietary recall to represent the general condition of food intakes, and the representativeness was limited and recall bias was unavoidable. Thirdly, in a cross-sectional study we can only prove association rather than causal relationship between the Chinese HFD index and MetS and its components. However, this was the first analysis based on the Dietary Guideline and Balance Diet Pagoda for Chinese Residents regarding HFD and MetS in Chinese urban adults. The Chinese HFD index developed by this study was comparable to that of other countries and made it possible to measure compliance with dietary guidelines quantitatively.

Conclusions

This study quantitatively described the status of MetS and the Chinese HFD index, and found that the Chinese HFD index was negatively associated with MetS and some of its components, such as elevated WC and elevated fasting glucose. Increased food diversity may lower the risk of MetS, which is important in designing dietary interventions for cardiac–cerebral vascular diseases. The study underscores the necessity of continued investigation into the role of healthful food diversity in the prevention of MetS and provides an integral framework for ongoing research.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

analysis of variance

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CFCT:

-

Chinese Food Composition Tables

- CHNS:

-

China Health and Nutrition Survey

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- CJFH:

-

specimen collection and processing by the China–Japan Friendship Hospital

- CUADHS:

-

Chinese Urban Adults Diet and Health Study

- CV:

-

coefficient of variation

- CVD:

-

cardiovascular disease

- DBP:

-

diastolic blood pressure

- DRIs:

-

Dietary Reference Intakes

- EAR:

-

estimated average requirements

- FAO:

-

Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations

- FFQ:

-

food frequency questionnaire

- FSG:

-

fasting serum glucose

- HDL:

-

high-density lipoprotein

- HFD:

-

healthful food diversity

- KNHANES:

-

Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- MET:

-

metabolic equivalents

- MetS:

-

metabolic syndrome

- MPA:

-

mean probability of adequacy

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- PA:

-

probabilities of nutrient adequacy

- RNI:

-

recommended nutrient intakes

- SBP:

-

systolic blood pressure

- TC:

-

total cholesterol

- TG:

-

triglyceride

- WC:

-

waist circumference

References

de Carvalho VF, Bressan J, Babio N, Salas-Salvado J. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Brazilian adults: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1198.

Beltran-Sanchez H, Harhay MO, Harhay MM, McElligott S. Prevalence and trends of metabolic syndrome in the adult U.S. population, 1999-2010. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(8):697–703.

Yeh CJ, Chang HY, Pan WH. Time trend of obesity, the metabolic syndrome and related dietary pattern in Taiwan: from NAHSIT 1993-1996 to NAHSIT 2005-2008. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2011;20(2):292–300.

Eckel RH, Alberti KG, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2010;375(9710):181–3.

Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, Fruchart JC, James WP, Loria CM, Smith SJ. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the international diabetes federation task force on epidemiology and prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; world heart federation; international atherosclerosis society; and International Association for the Study of obesity. Circulation. 2009;120(16):1640–5.

Moore JX, Chaudhary N, Akinyemiju T. Metabolic syndrome prevalence by race/ethnicity and sex in the United States, National Health and nutrition examination survey, 1988-2012. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:E24.

Tran BT, Jeong BY, Oh JK. The prevalence trend of metabolic syndrome and its components and risk factors in Korean adults: results from the Korean National Health and nutrition examination survey 2008-2013. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):71.

Xi B, He D, Hu Y, Zhou D. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its influencing factors among the Chinese adults: the China health and nutrition survey in 2009. Prev Med. 2013;57(6):867–71.

Xiao J, Wu CL, Gao YX, Wang SL, Wang L, Lu QY, Wang XJ, Hua TQ, Shen H, Cai H. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its risk factors among rural adults in Nantong, China. Sci Rep. 2016;6:380–9.

Xiao J, Wu C, Xu G, Huang J, Gao Y, Lu Q, Hua T, Cai H. Association of physical activity with risk of metabolic syndrome: findings from a cross-sectional study conducted in rural area, Nantong, China. J Sports Sci. 2016;34(19):1839–48.

Song QB, Zhao Y, Liu YQ, Zhang J, Xin SJ, Dong GH. Sex difference in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular-related risk factors in urban adults from 33 communities of China: the CHPSNE study. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2015;12(3):189–98.

Park JH, Kim SH, Lee MS, Kim MS. Epigenetic modification by dietary factors: implications in metabolic syndrome. Mol Asp Med. 2017;54:58–70.

de la Iglesia R, Loria-Kohen V, Zulet MA, Martinez JA, Reglero G, Ramirez DMA. Dietary strategies implicated in the prevention and treatment of metabolic syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(11):1877.

Lucke-Wold B, Shawley S, Ingels JS, Stewart J, Misra R. A critical examination of the use of trained health coaches to decrease the metabolic syndrome for participants of a community-based diabetes prevention and management program. J Health Commun. 2016;1(4):38.

Baik I, Lee M, Jun NR, Lee JY, Shin C. A healthy dietary pattern consisting of a variety of food choices is inversely associated with the development of metabolic syndrome. Nutr Res Pract. 2013;7(3):233–41.

de Oliveira EP, McLellan KC, Vaz DASL, Burini RC. Dietary factors associated with metabolic syndrome in Brazilian adults. Nutr J. 2012;11:13.

Kastorini CM, Milionis HJ, Esposito K, Giugliano D, Goudevenos JA, Panagiotakos DB. The effect of Mediterranean diet on metabolic syndrome and its components: a meta-analysis of 50 studies and 534,906 individuals. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(11):1299–313.

Azadbakht L, Esmaillzadeh A. Red meat intake is associated with metabolic syndrome and the plasma C-reactive protein concentration in women. J Nutr. 2009;139(2):335–9.

Aleixandre A, Miguel M. Dietary fiber in the prevention and treatment of metabolic syndrome: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2008;48(10):905–12.

Chung SJ, Lee Y, Lee S, Choi K. Breakfast skipping and breakfast type are associated with daily nutrient intakes and metabolic syndrome in Korean adults. Nutr Res Pract. 2015;9(3):288–95.

Nazare JA, Smith J, Borel AL, Almeras N, Tremblay A, Bergeron J, Poirier P, Despres JP. Changes in both global diet quality and physical activity level synergistically reduce visceral adiposity in men with features of metabolic syndrome. J Nutr. 2013;143(7):1074–83.

McCrory MA, Burke A, Roberts SB. Dietary (sensory) variety and energy balance. Physiol Behav. 2012;107(4):576–83.

Raynor HA. Can limiting dietary variety assist with reducing energy intake and weight loss? Physiol Behav. 2012;106(3):356–61.

Ruel MT. Operationalizing dietary diversity: a review of measurement issues and research priorities. J Nutr. 2003;133(11 Suppl 2):3911S–26S.

Tiew KF, Chan YM, Lye MS, Loke SC. Factors associated with dietary diversity score among individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Health Popul Nutr. 2014;32(4):665–76.

Vadiveloo M, Parekh N, Mattei J. Greater healthful food variety as measured by the US healthy food diversity index is associated with lower odds of metabolic syndrome and its components in US adults. J Nutr. 2015;145(3):564–71.

Vadiveloo M, Dixon LB, Mijanovich T, Elbel B, Parekh N. Dietary variety is inversely associated with body adiposity among US adults using a novel food diversity index. J Nutr. 2015;145(3):555–63.

Drescher LS, Thiele S, Mensink GB. A new index to measure healthy food diversity better reflects a healthy diet than traditional measures. J Nutr. 2007;137(3):647–51.

Vadiveloo M, Sacks FM, Champagne CM, Bray GA, Mattei J. Greater healthful dietary variety is associated with greater 2-year changes in weight and adiposity in the preventing overweight using novel dietary strategies (POUNDS lost) trial. J Nutr. 2016;146(8):1552–9.

Popkin BM, Du S, Zhai F, Zhang B. Cohort profile: the China health and nutrition survey: monitoring and understanding socio-economic and health change in China, 1989-2011. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(6):1435–40.

Standard Tables of Food Composition in Japan. Tokyo: Ishiyaku Publishers, Inc; 2010.

Zhao W, Yu K, Tan S, Zheng Y, Zhao A, Wang P, Zhang Y. Dietary diversity scores: an indicator of micronutrient inadequacy instead of obesity for Chinese children. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):440.

Kennedy G, Nantel G. Basic guidelines for validation of a simple dietary score as an indicator of dietary nutrient adequacy for non-breastfeeding children 2–6 years. ftp://ftp.fao.org/ag/agn/nutrition/dds_validation.pdf. Accessed 15 Apr 2006.

Frankenfeld CL, Poudrier JK, Waters NM, Gillevet PM, Xu Y. Dietary intake measured from a self-administered, online 24-hour recall system compared with 4-day diet records in an adult US population. Jacad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(10):1642–7.

Xue H, Yang M, Liu Y, Duan R, Cheng G, Zhang X. Relative validity of a 2-day 24-hour dietary recall compared with a 2-day weighed dietary record among adults in South China. Nutr Diet. 2017;74(3):298–307.

Nightingale H, Walsh KJ, Olupot-Olupot P, Engoru C, Ssenyondo T, Nteziyaremye J, Amorut D, Nakuya M, Arimi M, Frost G, et al. Validation of triple pass 24-hour dietary recall in Ugandan children by simultaneous weighed food assessment. BMC Nutr. 2016;2:56.

Chinese Nutrition Society. Chinese dietary guidelines summary (2016). Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House; 2017.

Vadiveloo M, Dixon LB, Mijanovich T, Elbel B, Parekh N. Development and evaluation of the US healthy food diversity index. Br J Nutr. 2014;112(9):1562–74.

World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Western Pacific. The Asia-Pacific perspective: redefining obesity and its treatment. Sydney: Health Communications Australia; 2000.

Remick AK, Polivy J, Pliner P. Internal and external moderators of the effect of variety on food intake. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(3):434–51.

Epstein LH, Robinson JL, Temple JL, Roemmich JN, Marusewski AL, Nadbrzuch RL. Variety influences habituation of motivated behavior for food and energy intake in children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(3):746–54.

Lassale C, Fezeu L, Andreeva VA, Hercberg S, Kengne AP, Czernichow S, Kesse-Guyot E. Association between dietary scores and 13-year weight change and obesity risk in a French prospective cohort. Int J Obes. 2012;36(11):1455–62.

Gregory CO, McCullough ML, Ramirez-Zea M, Stein AD. Diet scores and cardio-metabolic risk factors among Guatemalan young adults. Br J Nutr. 2009;101(12):1805–11.

Azadbakht L, Mirmiran P, Azizi F. Dietary diversity score is favorably associated with the metabolic syndrome in Tehranian adults. Int J Obes. 2005;29(11):1361–7.

Vadiveloo MK, Parekh N. Dietary variety: an overlooked strategy for obesity and chronic disease control. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(6):974–9.

Vadiveloo M, Dixon LB, Parekh N. Associations between dietary variety and measures of body adiposity: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Br J Nutr. 2013;109(9):1557–72.

Azadbakht L, Mirmiran P, Esmaillzadeh A, Azizi F. Dietary diversity score and cardiovascular risk factors in Tehranian adults. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9(6):728–36.

Danquah I, Galbete C, Meeks K, Nicolaou M, Klipstein-Grobusch K, Addo J, Aikins AD, Amoah SK, Agyei-Baffour P, Boateng D, et al. Food variety, dietary diversity, and type 2 diabetes in a multi-center cross-sectional study among Ghanaian migrants in Europe and their compatriots in Ghana: the RODAM study. Eur J Nutr. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-017-1538-4.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the data share of the CHNS work team.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

The data used and/or analysed during the current research are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The research question and study design were formulated by WZ and JZ. The study was carried out by WZ, JZ, AZ, MW, WW, ST, MG, and YZ. Data analysis was carried out by WZ and JZ. The article was written by all authors, with editing by WZ, AZ, and YZ.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by ethical review committees of Peking University Health Science Centre (no. IRB00001052–15059). All of the participants in the CUADHS provided written consent for participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Comparison of energy and macronutrients calculated from mean value of three-day 24-h dietary recalls and one-time 24-h dietary recall in the CUADHS. (DOCX 14 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S2. Measurement methods of anthropometry indicators and blood biochemical indices. (DOCX 15 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, W., Zhang, J., Zhao, A. et al. Using an introduced index to assess the association between food diversity and metabolic syndrome and its components in Chinese adults. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 18, 189 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-018-0926-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-018-0926-x