Abstract

Background

Endo-β-1,4-xylanase1 (EA), the key endoxylanase in plants, is involved in the degradation of arabinoxylan during grain germination. In barley (Hordeum vulgare L.), one gene (HvXYN-1) that encode a endo-beta-1,4-xylanase, has been cloned. However, the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that affect the endoxylanase activity and total arabinoxylan (TAX) content have yet to be characterized. The investigation of genetic variation in HvXYN1 may facilitate a better understanding of the relationship between TAX content and EA activity in barley.

Results

In the current study, 56 polymorphisms were detected in HvXYN1 among 210 barley accessions collected from 34 countries, with 10 distinct haplotypes identified. The SNPs at positions 110, 305, 1045, 1417, 1504, 1597, 1880 bp in the genomic region of HvXYN1 were significantly associated with EA activity (P < 0.0001), and the sites 110, 305, and 1045 were highly significantly associated with TAX content. The amount of phenotypic variation in a given trait explained by each associated polymorphism ranged from 6.96 to 9.85%. Most notably, we found two variants at positions 1504 bp and 1880 bp in the second exon that significantly (P < 0.0001) affected EA activity; this result could be used in breeding programs to improve beer quality. In addition, African accessions had the highest EA activity and TAX content, and the richest germplasm resources were from Asia, indicating the high potential value of Asian barley.

Conclusion

This study provided insight into understanding the relationship, EA activity, TAX content with the SNPs of HvXYN1 in barley. These SNPs can be applied as DNA markers in breeding programs to improve the quality of barley for beer brewing after further validation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) is an ancient crop that is distributed worldwide. Barley is an important raw material in beer brewing [1], and its quality directly affects the fermentation ability, flavor, turbidity or foam stability of beer. Studies of the molecular mechanisms underlying genetic and environmental variation and the quality differences in grain protein content, β-glucan content, β-amylase, limit dextrin enzyme activity and other traits related to barley quality have been reported [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Arabinoxylan (AX) is the principal non-cellulosic polysaccharide in the thick aleurone layer of the barley grain cell wall [10]. AX has an important influence on the brewing quality of barley, as it can affect the grain hardness and water absorption of seeds, hindering the release of endosperm substances. In the beer-brewing process, insufficient degradation of AX will hinder the release of hydrolytic enzymes from the thick aleurone layer or nutrients from the endosperm, and almost the non-degradable AX would flow into wort, increase viscosity, block subsequent filtration and processing, increase the turbidity of beer and influenced the flavor of beer or other beer qualities [11,12,13].

AX, which consists of a linear 1,4-linked backbone of D-xylopyranosyl residues with various side chains, is the main component of hemicellulose in cereals [14]. These side chains in AXs have been found to increase wort viscosity and decrease filterability [11, 12].. AXs are mainly degraded by the glycosyl hydrolases endo-β-1,4-xylanase (EA, further referred to as xylanase) (EC3.2.1.8), which can hydrolyse β-1,4-linkages between xylose residues in the backbone of these polysaccharides, and exo-β-1,4-xylosidase (EC3.2.1.37) [15, 16]. In cereals, these enzymes are involved in the depolymerization of arabinoxylan during seed germination [17]. Particularly in barley, xylanase can be synthesized and secreted in the aleurone layer [18]. However, due to the activity of xylanase in malt, a large amount of arabinoxylan is dissolved [13, 19], which in turn improves the viscosity, foam stability and sensory characteristics of beer [20].

Three endo-β-1,4-xylanase isoenzymes have been purified from germinating barley and shown to be endo-hydrolases on the basis of product analysis [21]. A cDNA which encoding endo-β-1,4-xylanase,with molecular weight of 41,000 D (Mr41 000) has been characterized during germinating barley [22, 23]. Caspers et al. [24] have identified the other major endo-β-1,4-xylanase (XYN-1) in the aleurone of germinating barley grains and the gene located in the long arm of chromosome 5H. It is expressed as a precursor of molecular weight 61,500 D (Mr61 500) with both N- and C-terminal pro-peptides and regulated the disintegration of aleurone cell.

The ability of different crop species to meet people’s needs is the result of sequence variation in genes in the accessions of the given crop species. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and small insertions and deletions (indels) are the most common forms of genetic variation in natural crop populations, and these polymorphisms may reflect the relationship of phenotypic variation and plant adaptation in different environments, thus playing a prominent role in the heritability of phenotypes [25]. Recently, association analysis has emerged as a powerful approach to identify the role of genetic polymorphisms in the phenotypic variation in beer barley. For example, Mohsen et al. [26] collected 1862 barley breeding lines and evaluated in 97 field trials about malting quality traits in barley through genome-wide association study. They found 108 and 107 significant marker-trait associations malting quality in all six-row and all two-row breeding programs and the distribution of favorable alleles for marker-assisted selection and germplasm exchange. Null LOX-1 activity varieties with stable foam in beer and better flavor of beer always were screened out as malting barley. Guo et al. [20] identified a rare C/G mutation (SNP-61) in the second intron which result in null LOX-1 activity through an altered splicing acceptor site and the SNP could be used in breeding programs for barley to be used for malting. In general, superior malting quality requires a high conversion of starch to fermentable sugars. Gong et al. [27] selected one gene, encodingβ-amylase, which could convert starch to sugars during malting as an indicator to improve malting quality; their results demonstrated that the broad variation in Bmy1 could provide novel alleles for the improvement of diastatic power and malting quality. Jin et al. [28] used structure-based association analysis to demonstrate that the key SNPs of HvLDI associated with limit dextrinase (LD) activity could be used to increase the conversion efficiency of conversion of starch to sugars during malting and improve the quality of beer. Hassan et al. [29] revealed three significant quantitative trait loci (QTL) associated with grain AX levels in barley through genome-wide association analysis., while they did not mentione the gene HvXYN1 The research conclusions concerning AX content are quite clear, but there are few studies of the relationship of EA activity and TAX content. To date, allelic variation of HvXYN1 in barley has not been systematically examined. Exploration of genetic variation in HvXYN1 may provide a better understanding of the functions of HvXYN1 and may yield useful information for improving the quality of barley.

In barley, only Caspers et al. [24] have cloned the endo-beta-1,4-xylanase gene (XYN-1). However, the key SNPs that were related to endo-xylanase activity and xylan content have yet to be reported. Therefore, to evaluate nucleotide diversity and to perform neutrality tests of detected regions, we detected allelic variation in the targeted region of HvXYN1 in 210 cultivated barley micro-nucleus germplasms collected from diverse geographical areas. In addition, association analysis between the allelic variations and EA activity and TAX content was performed to identify the key SNPs that significantly influencing TAX content and EA activity indifferent barley grain and to provide guidance for developing an allele-specific marker and improving beer barley quality by these key SNPs.

Results

Phenotypic variation

Significant amounts of genetic variation in EA activity and TAX content were observed among the 210 barley accessions (Fig. 1). The mean value of EA activity was 2.95 U/g, ranging from 1.97 U/g to 5.08 U/g; the value for TAX content was 5.95%, ranging from 1.76 to 13.29%. Moreover, normal distributions of EA activity and TAX content were observed (Fig. 1a, b), suggesting that multiple genes/QTLs control the focal traits in barley. Large phenotypic variation was observed for all traits; on the whole, the mean coefficient of variation (CV value) of TAX content (36%) was much larger than that of EA activity (19%), suggesting that the greater variation in TAX content is mainly controlled by genetic factors and is affected by environmental variation. In addition, the TAX content variation reached 36%, which further indicated that it was more vulnerable to environmental variation. The values of the two traits were significantly and positively correlated (R2 = 0.135*) (Table 1).

The frequency distribution of EA activity and TAX content of the examined barley accessions. The histogram indicates the phenotypic distribution frequency, and the curve indicates the fitted normal curve. The X axis represents EA activity and TAX content; the Y axis represents frequency of EA activity and TAX content. a The frequency distribution of EA activity. b The frequency distribution of TAX content

Nucleotide polymorphisms in HvXYN1

By amplifying the genomic region of HvXYN1 which is located in the long arm of chromosome 5H in barley, 142 natural variation sites were identified among the 210 accessions by sequencing analysis (Table 2). Nucleotide diversity (π) of the targeted region of HvXYN1 was 0.00736 across 210 barley accessions. The π values differed among geographic regions, ranging from 0.0018 for east European accessions (4 accessions) to 0.0103 for east Asia accessions (46 accessions) (Table 2). To test whether the identified nucleotide polymorphisms were selectively neutral, D*, F* and Tajima’s D statistics were calculated. For the 210 barley accessions, Tajima’s D value was − 1.48, but this was not significant (P > 0.05). However, the values of D* and F* were highly significant. Apart from the Asian and European accessions, other subgroups were from Africa, Middle East Asia and North East Asia, suggesting that the gene has not been under strong selection. However, the values of Tajima’s D from East Africa were statistically significant (P < 0.05) (Table 2). This suggests that nucleotide variation in the HvXYN1 gene in Africa did not result from standard neutral evolution.

Population structure and genetic diversity

In the correlation analysis, the population structure was taken into account to avoid false positive results. Analysis of genetic distance and population structure confirmed the presence of significant structure in the barley population. The 35 SSR markers were used to evaluate the subset of 210 varieties genotypes. Stratification within the barley population was detected by STRUCTURE. The largest value of the statistical index ΔK was used as an indicator of the most probable number of subpopulations for all accessions (Fig. 2). The ΔK value attained a clear maximum at K = 5, and the five groups (or clusters) revealed relatively low levels of admixture, with groups G1, G2, G3, G4 and G5 containing 46,13,47,43 and 51 accessions, respectively (Fig. 3).

Population structure of 210 barley accessions based on 35 SSRs (K = 5). Five colors indicate the subpopulations G1, G2, G3, G4 and G5, respectively. Each accession is represented by a thin vertical line with the lengths proportional to each of the subpopulations. The y-axis is the subgroup membership, and the x-axis is the accessions in the five groups (G1, G2, G3, G4 and G5)

Species geographical information

The geographical distribution of the 210 cultivars used in the analysis comprised 37 from Africa, 112 from Asia, and 61 from Europe (Table 3). Analysis of regional information of EA activity and TAX content revealed that EA activity in cultivars from Africa (3.487 U/g) was significantly higher than that of cultivars from Asia and Europe. In addition, Europe (2.781 U/g) had the lowest activity (Fig. 4a and Additional file 1: Table S1); African cultivars had significantly higher TAX content than those from Asia and Europe, with Asia being the lowest (Fig. 4b and Additional file 1: Table S1).

Comparisons of the EA activity and TAX content in different regions. a EA activity contrasts in different geographic regions. b TAX content contrasts in different geographic regions. ** indicates highly significant (P < 0.01) difference between means. The Duncan multiple range test and critical test were conducted if the analyses were significant (P < 0.05)

Associated SNP loci and haplotypes

Association analysis was performed to find possible links between nucleotide variation in HvXYN1 and barley xylan-related traits. Sequencing identified 56 SNPs in the targeted region of HvXYN1. Among the 56 SNPs, 53 were from coding regions and three were from non-coding regions. Of the former, three were significantly associated with the two focal phenotypic traits. The SNPs at positions 110, 305, 1045, 1417, 1504, 1597, 1880 bp in the genomic region of HvXYN1 were significantly associated with EA activity (P < 0. 001), and these explained 5.8, 5.8, 8.0, 8.8, 9.9, 6.3 and 7.0% of the phenotypic variation, respectively (Table 4, Additional file 2: Figure S1 and Additional file 3: Figure S3). Haplotype-trait associations were restricted to haplotypes with a higher than 5% frequency of minor alleles. The 210 barley accessions analyzed contained ten haplotypes (EH1-EH10) (Fig. 5a) according to the seven significant association SNPs (Table 4). Among these, the EH8-EH10 haplotypes were present in much lower frequency and were excluded from further analysis. Thus, only seven haplotypes (EH1-EH7) were used in the association analysis. The mean value of the EH6 haplotype for EA was 3.63 U/g; this was higher than those of haplotypes EH2 and EH3 (P < 0. 05) and was significantly higher than those of haplotypes EH1, EH4, and EH5 (P < 0. 01) (Fig. 6a and Additional file 4: Table S2). EH4 had the lowest endo-xylanase activity (2.644 U/g), significantly lower than the values of haplotypes EH1, EH2, EH3 and EH6 (P < 0.01). Further analysis revealed that the highest-activity (EH6) and lowest-activity (EH4) mutations were located at 1504 bp and 1880 bp, respectively, and that the activities of EH1 and EH2 were also significantly higher than that of EH3. The unique variation site was occurred at 1504 bp. This C-G transversion at 1504 bp may have caused the decrease in EA activity. The EA activity at 1504 bp allele C was 3.07 U/g, which was significantly higher than allele G (2.78 U/g) (Fig. 7a and Additional file 5: Table S3). Thus, SNP 1504 was considered as the candidate variant affecting EA activity. The variation of allele G to C at 1880 bp resulted in an amino acid mutation from valine to leucine. The phenotypic analysis revealed that EA activity at this site with G (3.01 U/g) was significantly higher than with C (2.66 U/g); we therefore speculated that the G/C mutation at 1880 bp resulted in the changes of EA activity. The sites 110, 305, and 1045 consisting of three haplotypes (TH1-TH3) (Fig. 5b, Additional file 6: Figure S2, and Additional file 3: Figure S3) were highly significantly associated with TAX content and explained 6.5, 6.5 and 5.4% of the phenotypic variation for TAX content, respectively. However, the TAX content of the three haplotypes did not reach significant differences. The highest (TH3) TAX content was 6.99% and the lowest (TH1) was 5.96%; the two values were not significantly different (P > 0.05) (Fig. 6b and Additional file 4: Table S2). Three SNPs (110, 305, 1045) significantly associated with EA activity and TAX content, which would be the key SNPs that affect the traits of xylan. There were seven SNPs significantly associated with EA activity, while only one marker in 1880 bp is biologically significant. Therefore, we speculate that 1880 bp can be used in marker-assisted selection to improve the quality of beer barley but it still need be further experiment validation.

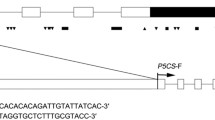

Haplotype analysis of the HvXYN1 gene region in the 210 accessions of EA activity and TAX content. The XYN1 sequence contained three exons (indicated in black boxes), two introns (indicated in white boxes) and the full length of 1926 bp genome is shown at the top of the diagram. The position of each SNP is shown in the first row as described in Table 4 (SNP frequency > 5%). Ten haplotypes (EH1-EH10) were detected in the EA activity (a) and three were detected in the TAX activity (b) among all the accessions. The number of accessions (No. accession) in different haplotypes is shown in the far right columns, and amino acid change variation corresponding to the SNPs is shown in the last row. Capital letters in this row represent the amino acid as follows P: Proline; N: Asparagine; V: Valine; G: Glycine; A: Alanine; V: Valine; L: Leucine

EA activity and TAX content contrasts in different haplotypes. a EA activity contrasts in different haplotypes (EH1-EH7). The EH6 haplotype had the highest EA activity, significantly greater than the other haplotypes (P < 0.05). EH4 had the lowest EA activity, significantly lower than the other haplotypes except for EH5 (P < 0.05). b TAX content contrasts in different haplotypes (TH1-TH3). TH3 had the highest mean TAX content, and TH1 had the lowest mean TAX content, but neither reached significance level. The X-axis shows the haplotype of EA and TAX described in Fig. 4, and the Y-axis shows the corresponding EA activity and TAX content

EA activity contrasts of different allelic forms. a At position 1504 bp, the EA activity of the C base form is significantly higher than that of the G base form. b At the position of 1880 bp, the EA activity of the G base form is significantly higher than that of the C form. The X-axis indicates the allele; the Y-axis shows the EA activity. ** indicates highly significant level (P < 0.01) of difference between means. –indicates that the base was deleted

Regional distribution of different haplotypes

Analyzing the distribution of haplotypes in different region, we found that the distributions of EH1, EH2, EH3, EH4, and EH5 were nonrandom. The haplotype EH6 was mainly distributed in Africa (Fig. 8a) and had higher enzyme activity (Fig. 6a). The lower-activity haplotype EH4 was mainly distributed in Europe and western Asia. This result was consistent with the EA active regional distribution, supporting the hypothesis that the EH6 haplotype is correlated with the high EA activity observed in Africa.

The geographic distribution of different haplotypes in HvXYN1. EH (EH1–EH7) and TH (TH1-TH3) represent haplotypes as described in Fig. 4. a The distribution of the haplotypes in EA activity among different geographic locations. b The distribution of the haplotypes in TAX content among different geographic location. The X axis represents the different geographic location, the Y axis represents percentage of haplotypes in EA activity and TAX content

For the distribution of TAX traits, there were three haplotypes (TH1, TH2, and TH3) that were distributed in Africa, Europe, and Asia (Fig. 8b). TH1 had the most extensive distribution; TH2 was most widely distributed in Europe, followed by Africa and Asia; TH3 was less widely distributed in the three regions. The TH1 haplotype with the lowest TAX content was the Maximum distribution, while the TH3 haplotype with the highest TAX content had only three varieties, indicating that the TAX content in different regions was mainly affected by the TH1 haplotype. The genotype of the TH1 haplotype was consistent with the haplotypes EH1, EH2, EH3, EH4, and EH6 affecting EA activity. Moreover, EH4 had the lowest EA activity and EH6 had the highest, indicating that EA activity had little effect on TAX content. TH3 had three accessions, so the result is not representative.

Discussion

The XYN1 gene has been cloned in several grass plant species [22, 30, 31], but its key SNPs have not been characterized. In this study, 56 natural variation sites were identified from 1892 bp of the DNA sequence of HvXYN1 across 210 barley accessions. The SNPs were distributed unevenly along the DNA sequence, with 53 and 3 variation sites in the exon and intron regions, respectively. Notably, the third exon contained the greatest nucleotide variation. Several studies have demonstrated a low level of polymorphism in exon regions and a high level in non-coding regions of barley [32,33,34,35], but the opposite result was observed in our research. There was a high level of polymorphism in exon regions of HvXYN1. It might be due to that the increased yield or disease resistance genes have gone through stronger selective pressures during domestication and breeding [36, 37]. HvXYN1 encodes endo-beta-1,4-xylanase which mainly degraded xylan during germinating barley from the aleurone layer. Endo-beta-1,4-xylanase have an influence one content of xylan during seed germination, while it contributes little influences to the germination of seed or the growth of plants. The other reason is that, the domestication of barley, gene flow was not an isolated event but probably a continuous process. Indeed, the genome of a 6000-yr-old barley landrace carried signatures of the wild barley introgressions [38].

Tajima’s D measures the deviation from neutral evolution by comparing diversity estimates based on nucleotide diversity and average pairwise nucleotide diversity (π). In this study, the Tajima’s D test was performed on the HvXYN1 sequence, yielding a value of − 1.44863 (Table 2). While this was below the significant statistically level, the values of D* and F* were significant, indicating that the evolution of the gene is basically in accord with the principle of neutral evolution. However, a negative Tajima’s D indicates population size expansion (for example, following a bottleneck or a selective sweep) or purifying selection [39,40,41]. This may be the reason for the low number of SNPs observed, in accord with previous research on other functional genes in barley [42,43,44]. However, in east Africa, the percent polymorphism was 0.0438, and the value of Tajima’s D was 2.123* and was statistically significant at the P < 0.05 level, suggesting that the gene may be experiencing negative selection to maintain a lower mutation rate, so that favorable alleles have been strongly positively selected [39,40,41]. Compared to previous research on barley [42, 45, 46], nucleotide diversity (π = 0.00736) and haplotype diversity (Hd = 0.923) of HvXYN1 were relatively high in this study. The differences in SNP frequency among studies may be due to differences in genomic regions assayed, or the number, content and geographic origins of the germplasm used [47,48,49]. In comparing the gene polymorphisms of HvXYN1 from different regions, the barley germplasm from East Asia showed the highest level of nucleic acid polymorphism (π = 0.0103), consistent with previous research results [44, 50, 51]. One probable reason is that these geographic regions were the main distribution areas of wild barley [52].

Association analysis is one powerful method to explore the relationship between sequence polymorphisms and phenotype variation [53]. In the present study, seven variants of HvXYN1 were significantly (P < 0.001) associated with xylan-related traits in barley. Among these, one variant at 110 bp of HvXYN1 was within an intron region, while the other six at positions 305 bp, 1045 bp, 1417 bp, 1504 bp, 1597 bp and 1880 bp were within exons. Meanwhile, three variants (at positions 110 bp, 305 bp and 1045 bp) were associated with TAX content but were not significant. Xia et al. [44] discovered a synonymous mutation associated with phenotypic traits. In our study, there was also one SNP at 1504 bp, a synonymous mutation of G to C, that significantly increased EA activity (Fig. 7a), although this did not cause structural change of the gene product. A reasonable explanation for this phenomenon was the hitchhiking effect of a locus undergoing positive selection [54] or a false positive association. Thus, the SNPs identified by the association analysis should be validated before they can be applied to marker-assisted selection in the progeny [55, 56]. In addition, epigenetic or post-transcriptional regulation presumably affected the change in EA activity. Notably, a nonsynonymous amino acid substitution in the third exon of the HvXYN1 gene at 1880 bp (C) has contributed to the low EA activity phenotype (Fig. 7b). Thus, the changes in the functional properties of the enzyme were likely caused by the change of bases [20, 57]. How the amino acid substitutions of different sequences impact the EA activity remains unclear. Further research using a quantitative xylanase method will be required to understand the relationship between non-synonymous mutations and EA activity. The change of V to L at this site may also indicate that it was an important SNP and that it can provide an important genetic resource for barley breeding research.

In agreement with the results of previous studies [58], TAX content had a greater CV (36%) in barley malt. One possible reason is that TAX content may be greatly affected by environmental factors. EA activity and TAX content were significantly and positively correlated (R2 = 0.135*) (Table 1) and the result suggest that EA activity and TAX content would be controlled by a common factor. We examined the geographical distribution of these haplotypes and found that there was no significant difference among the three haplotypes of TAX, but there was significantly higher diversity in Africa than in Europe and Asia. This may be due to the tropical location of Africa; for example, water deficiency and drought-induced stress could increase TAX content [59]. The EH6 haplotype with the highest EA activity (3.628 U/g) was mainly distributed in Africa, while the lowest (EH4) haplotype was mainly distributed in Europe. The current results suggested that AX content in malt could be not only related to EA but also be controlled by specific enzymes. Previous reports concerning the hydrolysis of AX during malting found that endoxylanase activity rose sharply after 72 h germination [60]. Thus, it is not difficult to understand why the accumulation of TAX content in African varieties induced enhanced EA activity in our study. In addition, barley has different uses in different regions. In European regions, barley is mostly used for beer brewing, which requires a lower TAX content; however, in Africa, barley is still an important food crop. Therefore, the EH6 haplotype that leads to high EA activity is mainly distributed in Africa, while the H4 haplotype with low EA activity is mainly found in Europe and Asia.

Conclusion

This study identified 10 unique haplotypes based on 56 variations in HvXYN1 among 210 barley accessions collected from 34 countries. Seven SNPs and seven haplotypes were significantly (P < 0.001) associated with EA activity and TAX content in barley. These SNPs can be applied as DNA markers in breeding programs to improve the quality of barley for beer brewing after further validation.

Methods

Plant materials and planting

A set of 210 barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) accessions sourced from 34 countries in three adjacent geographic regions, including Asia, Africa and Europe, (Table 3 and Additional file 7: Table S4). The 210 barley accessions were planted in Hangzhou Normal University (N30°19′7.12′′ N, E 120°23′7.89′′ E) test field. The sowing date were mid-November in 2014 and 2015, respectively. Each cultivar was grown in a plot, consisting of three lines. The plots were arranged by a randomized block design with three replications. At maturity, the middle line of each plot was harvested. After dried in an oven, about 20 g seeds from each plot were ground with a sample mill (Tesite instrument company, Tianjin, China) to pass through a 0.5-mm sieve and stored at ambient temperature for further chemical assay.

PCR amplification and sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from leaf of each accession using CTAB method [61]. The primers used for DNA amplification were designed using the primer 3 online tool (http://primer3.ut.ee/). Through the primer walking technique, three overlapping oligos were designed to amplify 1926 bp of the gene. Details of primers were given in Additional file 8: Table S5. The PCR reactions were completed as following: 25 μL of 10 × KOD buffer, 10 μL of 2 mM dNTPs, 2.5 μL of 10 μM forward primers, 2.5 μL of 10 μM reverse primer, 4 μL of genomic DNA and 5 μL of ddH2O for each sample. The PCR amplification programs were as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 34 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s, annealing at 56 °C for 30 s, and extension at 68 °C for 1.0 min followed by final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR products were analyzed by 5% agarose gel electrophoresis in 0.5 × TBE buffer. All the product was sent to Hangzhou Zhixiu Technology Co. Ltd. for sequencing. Then the SeqMan program in the Lasergene software was used for splicing.

Determination of total arabinoxylan (TAX) content in barley

Determination of total arabinoxylan (TAX) content, referred to the methods described by previous studies [58, 62, 63] with slightly improvements: 0.1 g sample mixed with 4 mL H2SO4 (1 mol L-1) in 1.5 mL centrifuge tube, then extracted in boiled water for 10 min, and cooled to room temperature. Centrifuged at 6000 rmp·min-1 for 5 min, took 1 mL of supernatant into a 15 mL centrifuge tube, added an equal volume of H2O, then added 10 mL of reaction solution (110 mL glacial acetic acid, 2 mL conc. HCL, 1 mL 1.75 g (1 mL glucose, 5 mL of 10% phloroglucinol-ethanol solution) and mixed. After reacted for 25 min in boiling water, cooled rapidly to room temperature and stopped the reaction. Determine by dual wavelength method (552 nm and 510 nm) and the difference in absorbance of the reaction solution was calculated, the total arabinoxylan content in the sample was calculated according to the standard curve. Each measurement was done with three replications.

Determination of EA activity

Sprouted barley samples were homogenized in a mortar and grind rapidly in ice-cold homogenisation buffer (50 mM sodium acetate pH 5.0 containing 250 mM NaCl, 0.1% (w/v) polyvinyl polypyrrolidine (PVPP) and 0.5% (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma product P9599) at 2.5 ml/g malt [64]. The addition of 250 mM NaCl and PVPP enhanced recovery of endoxylanase activity. After leaving for 20 min at 0 °C, insoluble material was removed by centrifugation. The supernatant homogenate was filtered through Whatman GF/C glass fibre filters. Prior to analysis by dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS), fractional precipitation of the soluble extracted overnight against 10 mM sodium acetate pH 5.0. The dialysates were applied to a cation exchange column (Resource-S, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Ltd) pre-equilibrated in 10 mM sodium acetate pH 5.0 and eluted with a gradient of 0–500 mM NaCl in the same buffer over 25 min.

The activity of endoxylanase was determined using dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) [65, 66] with the commercial xylose (Sigma) as a standard curve. The basic principle of the method is that xylanase could catalyze xylanase to produce reduced sugars such as xylose under certain conditions. Reducing sugar with DNS could produce chromogenic reaction. 1.0% birchwood 4-O-methyl glucuronoxylan (Roth 7500) in 0.05 M Na-citrate buffer, pH 5.3. 1.0 g of xylan fully dissolved in 80 ml buffer at 60 °C and heated to the boiling point. Then cooled with continued stirring, covered and mixt slowly overnight. The following day made up to 100 ml with buffer. Store at 4 °C for a maximum of 1 week or freeze aliquots of e.g. 25 ml at − 20 °C~ Mix well after thawing. First added 1.8 ml oat xylan as substrate solution and 200 μL enzyme diluted appropriately in citrate buffer to a 15 ml test tube. Incubated the mixture for 5 min, at 50 °C. Then added 3.0 ml DNS, mixed and removed the tube to the water bath. Boil for 5 min, then cool quickly in cold water. Measure the colour produced at 540 nm against the reagent blank. Corrected the absorbance for background colour in the enzyme blank (add 200 μL buffer) if necessary. Used the standard line, convert the corrected absorbance to enzyme activity units (1 μmol/min). Calculate the activity, which is mean the amount of enzyme to generate 1 μmol xylose in one minute.

Population structure analysis

The barley germplasm collection was structured into geographical groups in which some individuals were possibly related, so background genetic effects needed to be controlled to avoid spurious associations. Incorporating structure components as covariates in association analysis helps to reduce the false associations [67]. All of the accessions were genotyped using 35 SSR markers assigned to seven chromosomes of barley (Additional file 9: Table S6). Amplification of the SSRs was carried out as described by Hayden et al. [68]. Amplified PCR products were scored by comparing sizes between PCR products and a molecular weight ladder. Data from the 35 SSR markers were used to determine the population structure. Program STRUCTURE version 2.3.3 [69, 70] was used for population structure analysis, in which the number of clusters (k) was set from 2 to 11, and ten iterations were performed in an admixture model with a 10,000 iteration burn-in period and 100,000 MCMC (Markov Chain Monte Carlo) iterations. The most probable number of clusters (k) was estimated according to the value of ΔK. When ΔK had the highest value, the value of k indicated the number of clusters [71]. The optimal number of subpopulations was determined by the statistic ΔK based on the rate of change of the likelihood value [72].

Association analysis and statistical analysis

The multiple genomic sequences were aligned by ClustalW 2.0.9 [73]. Sequence start and end adjustment was performed using the BioEdit V7.2.5 software, and the alignment results were used as input into TASSEL 3.0 [74], where the SNP was considered as a fixed effect. Association analysis between SNP markers in XYN1 and EA activity and TAX content related traits was evaluated using a general linear model (GLM_Q) in TASSEL v3.0 (http://www.maizegenetics.net/tassel), where the SNP was considered as a fixed effect and the factor matrix of subpopulation membership (Q matrix) was used as a cofactor to account for population structure. The significance of associations between markers and traits was tested using an F-test. The association between a marker and a trait is represented by its R2 value, an estimate of the percentage of phenotypic variation explained by the marker. Haplotypes with a frequency < 5% were discarded to avoid biased associations. Nucleotide diversity (π), haplotype diversity, Tajima’s D [41] and D* and F* [39] values were calculated using the DnaSP 5.0 program [75]. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) was estimated by using standardized disequilibrium coefficients (D’) and squared allele-frequency correlations (R2) for pairs of SNP loci according to the TASSEL program. Polymorphism information content (PIC) was calculated as described in Kota et al. [76]. TASSEL was also used to identify SNP trait associations by generating a general linear model (GLM). The Duncan multiple range test and critical test were conducted if the analyses were significant (P < 0.05). Correlations between three traits and gene expression levels were examined by the Spearman correlation coefficient test. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using the MEGA7 software with the following parameters: tested neighbor joining tree, Poisson correction, pairwise deletion, and bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates [77].

Abbreviations

- EA:

-

endo-β-1,4-xylanase

- SNPs:

-

single nucleotide polymorphisms

- TAX:

-

total arabinoxylan

- XYN1:

-

Endo-β-1,4-xylanase1

References

Jamar C, Jardin PD, Fauconnier ML. Cell wall polysaccharides hydrolysis of malting barley (Hordeum vulgare L.): a review. Biotechnologie Agronomie Société Et Environnement. 2011;15(2):301–13.

Zhang G, Junmei W, Jinxin C. Analysis of β-glucan content in barley cultivars from different locations of China. Food Chem. 2002;79(2):251–4.

Wang J, Zhang G, Chen J, Wu F. The changes of β-glucan content and β-glucanase activity in barley before and after malting and their relationships to malt qualities. Food Chem. 2004;86(2):223–8.

Qi JC, Zhang GP, Zhou MX. Protein and hordein content in barley seeds as affected by nitrogen level and their relationship to beta -amylase activity. J Cereal Sci. 2006;43(1):102–7.

Wei K, Xue DW, Jin XL, Wu FB, Zhang GP. Genotypic and environmental variation of β-amylase activity, β-glucan and protein fraction contents in Tibetan wild barley. J Zhejiang Univ. 2009;35(6):639–44.

Houston K, Russell J, Schreiber M, Halpin C, Oakey H, Washington JM, Booth A, Shirley N, Burton RA, Fincher GB. A genome wide association scan for (1,3;1,4)-β-glucan content in the grain of contemporary 2-row spring and winter barleys. BMC Genomics. 2014;15(1):1–15.

Jin X, Cai S, Ye L, Chen Z, Zhou M, Zhang G. Association of HvLDI with limit dextrinase activity and malt quality in;barley. Biotechnol Lett. 2013;35(4):639–45.

Ye L, Dai F, Qiu L, Sun D, Zhang G. Allelic diversity of a beer haze active protein gene in cultivated and Tibetan wild barley and development of allelic specific markers. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59(13):7218.

Singh S, Tripathi RK, Lemaux PG, Buchanan BB, Singh J. Redox-dependent interaction between thaumatin-like protein and β-glucan influences malting quality of barley. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(29):7725–773010.

Fincher GB. Cell walls and their components in cereal grain technology. Adv Cereal Sci Technol. 1986;8:207–95.

Lu J, Li Y. Effects of arabinoxylan solubilization on wort viscosity and filtration when mashing with grist containing wheat and wheat malt. Food Chem. 2006;98(1):164–70.

Sadosky P, Schwarz PB, Horsley RD. Effect of AX, β-glucans, and dextrins on the viscosity and membrane filterability of a beer model solution. J Am Soc Brew Chem. 2002;60(4):153–62.

Viëtor RJ, Voragen AGJ, Angelino SAGF. Composition of non-starch polysaccharides in wort and spent grain from brewing trials with malt from a good malting quality barley and a feed barley. J Inst Brew. 1993;99(3):243–8.

Timell TE. Recent progress in the chemistry of wood hemicelluloses. Wood Sci Technol. 1967;1(1):45–70.

Gubler F. The release of α-amylase through gibberellin-treated barley aleurone cell walls : an immunocytochemical study with Lowicryl K4M. Planta. 1987;172(2):155–61.

Fincher GB. Cell wall metabolism in barley. Biotechnol Agric. 1992.

Fincher GB. Molecular and cellular biology associated with endosperm mobilization in germinating cereal grains. Ann rev plant Physiol plant Molbiol. 1989;40(40):305–46.

Taiz L. Production of Cell Wall hydrolyzing enzymes by barley Aleurone layers in response to gibberellic acid. Plant Physiol. 1976;58(3):380–6.

Debyser W, Derdelinckx G, Delcour JA. Arabinoxylan and arabinoxylan hydrolysing activities in barley malts and worts derived from them. J Cereal Sci. 1997;26(1):67–74.

Guo G, Dondup D, Yuan X, Gu F, Wang D, Jia F, Lin Z, Baum M, Zhang J. Rare allele of HvLox-1 associated with lipoxygenase activity in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2014;127(10):2095–103.

Slade AM, Høj PB, Morrice NA, Fincher GB. Purification and characterization of three (1----4)-beta-D-xylan endohydrolases from germinated barley. Eur J Biochem. 1989;185(3):533–9.

Banik M, Garrett TPJ, Fincher GB. Molecular cloning of cDNAs encoding (1→4)-β-xylan endohydrolases from the aleurone layer of germinated barley (Hordeum vulgare). Plant Mol Biol. 1996;31(6):1163–72.

Banik M, Li CD, Langridge P, Fincher GB. Structure, hormonal regulation, and chromosomal location of genes encoding barley (1å4)-β-xylan endohydrolases. Mol Gen Genet MGG. 1997;253(5):599–608.

Caspers MP, Lok F, Sinjorgo KM, van Zeijl MJ, Nielsen KA, Cameronmills V. Synthesis, processing and export of cytoplasmic endo-beta-1,4-xylanase from barley aleurone during germination. Plant J Cell Mol Biol. 2001;26(2):191–204.

Russell J, Mascher M, Dawson IK, Kyriakidis S, Calixto C, Freund F, Bayer M, Milne I, Marshallgriffiths T, Heinen S. Exome sequencing of geographically diverse barley landraces and wild relatives gives insights into environmental adaptation. Nat Genet. 2016;48(9):1024.

Mohammadi M, Blake TK, Budde AD, Chao S, Hayes PM, Horsley RD, Obert DE, Ullrich SE, Smith KP: A genome-wide association study of malting quality across eight U.S. barley breeding programs. Theor Appl Genet. 2015;128(4):705–21.

Gong X, Westcott S, Zhang XQ, Yan G, Lance R, Zhang G, Sun D, Li C. Discovery of novel Bmy1 alleles increasing beta-amylase activity in Chinese landraces and Tibetan wild barley for improvement of malting quality via MAS. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e72875.

Jin X, Cai S, Ye L, Chen Z, Zhou M, Zhang G. Association of HvLDI with limit dextrinase activity and malt quality in barley. Biotechnol Lett. 2012;35(4):639–45.

Hassan AS, Houston K, Lahnstein J, Shirley N, Schwerdt JG, Gidley MJ, Waugh R, Little A, Burton RA. A genome wide association study of arabinoxylan content in 2-row spring barley grain. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182537.

Fongyih B, Wu SSH, Ratnayake C, Walling LL, Nothnagel EA, Huang AHC. The predominant protein on the surface of maize pollen is an endoxylanase synthesized by a tapetum mRNA with a long 5′ leader. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(32):22884-94.

Suzuki M, Kato A, Nagata N, Komeda Y. A xylanase, AtXyn1, is predominantly expressed in vascular bundles, and four putative xylanase genes were identified in the Arabidopsis thaliana genome. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002;43(7):759–67.

Duran C, Appleby N, Vardy M, Imelfort M, Edwards D, Batley J. Single nucleotide polymorphism discovery in barley using autoSNPdb. Plant Biotechnol J. 2009;7(4):326–33.

Oliver RE, Islamovic E, Obert DE, Wise ML, Herrin LL, Hang A, Harrison SA, Ibrahim A, Marshall JM, Miclaus KJ: Comparative systems biology reveals allelic variation modulating Tocochromanol profiles in Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). PloS One 2014, 9(5):e96276.

Uçarlı C, Mcguffin LJ, Çaputlu S, Aravena A, Gürel F. Genetic diversity at the Dhn3 locus in Turkish Hordeum spontaneum populations with comparative structural analyses. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20966.

Xia Y, Li R, Bai G, Khm S, Varshney RK, Baum M, Yan G, Guo P. Genetic variations of HvP5CS1 and their association with drought tolerance related traits in barley (Hordeum vulgarel.). Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1):7870.

Ma Y, Liu M, Stiller J, Liu C. A pan-transcriptome analysis shows that disease resistance genes have undergone more selection pressure during barley domestication. BMC Genomics. 2019;20(1):12.

Preece C, Livarda A, Christin PA, Wallace M, Martin G, Charles M, Jones G, Rees M, Osborne CP. How did the domestication of Fertile Crescent grain crops increase their yields? Funct Ecol. 2017;31(2):387–97.

Mascher M, Schuenemann VJ, Davidovich U, Marom N, Himmelbach A, Hübner S, Korol A, David M, Reiter E, Riehl S, Schreiber M, Vohr SH, Green RE, Dawson IK, Russell J, Kilian B, Muehlbauer GJ, Waugh R, Fahima T, Krause J, Weiss E, Stein N. Genomic analysis of 6,000-year-old cultivated grain illuminates the domestication history of barley. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1089–93.

Fu YX, Li WH. Statistical tests of neutrality of mutations. Genetics. 1993;133(3):693–709.

Simonsen KL, Churchill GA, Aquadro CF. Properties of statistical tests of neutrality for DNA polymorphism data. Genetics. 1995;141(1):413.

Tajima F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics. 1989;123(3):585–95.

Cseri A, Korff MV, Nagy B, Horváth GV, Palágyi A, Pauk J, Dudits D, Törjék O. Allele mining and haplotype discovery in barley candidate genes for drought tolerance. Euphytica. 2011;181(3):341–56.

Costanza J, Davis EL, Mulholland JA, Pennell KD. Geographical variation and differential selection modes of paralogs of chloroplast small heat shock protein genes in Machilus kusanoi (Lauraceae). Bot Stud. 2010;51(1):27–36.

Xia Y, Li R, Ning Z, Bai G, KHM S, Yan G, Michael B, Varshney RK, Guo P. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms inHSP17.8 and Their Association with Agronomic Traits in Barley. Plos One. 2013;8(2):e56816.

Wu D, Long Q, Xu L, Ye L, Chen M, Sun D, Chen Z, Zhang H, Jin X, Fei D. Genetic variation ofHvCBFGenes and their association with salinity tolerance in Tibetan annual wild barley. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e22938.

Xia Y, Li R, Ning Z, Bai G, KHM S, Yan G, Baum M, Varshney RK, Guo P. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in HSP17.8 and Their Association with Agronomic Traits in Barley. Plos One. 2013;8(2):e56816.

Bundock PC, Henry RJ. Single nucleotide polymorphism, haplotype diversity and recombination in the Isa gene of barley. Theor Appl Genet. 2004;109(3):543.

Russell J, Booth A, Fuller J, Harrower B, Hedley P, Machray G, Powell W. A comparison of sequence-based polymorphism and haplotype content in transcribed and anonymous regions of the barley genome. Genome. 2004;47(2):389-98.

Duran C, Appleby N, Vardy M, Imelfort M, Edwards D, Batley J. Single nucleotide polymorphism discovery in barley using autoSNPdb. Plant Biotechnol J. 2010;7(4):326–33.

Malysheva-Otto LV, Ganal MW, Röder MS. Analysis of molecular diversity, population structure and linkage disequilibrium in a worldwide survey of cultivated barley germplasm ( Hordeum vulgare L.). BMC Genetics. 2006;7(1):6.

Varshney RK, Baum M, Guo P, Grando S, Ceccarelli S, Graner A. Features of SNP and SSR diversity in a set of ICARDA barley germplasm collection. Mol Breed. 2010;26(2):229–42.

Ceccarelli S. Barley landraces of the fertile crescent offer new breeding options for stress environments. Diversity-Arlington Then Washington. 1995;11:112–3.

Zhu C, Gore M, Buckler ES, Yu J. Status and prospects of association mapping in plants. Plant Genome. 2008;1(1):5–20.

Thornton K, Jensen J, Becquet C, Andolfatto P. Progress and prospects in mapping recent selection in the genome. Heredity. 2007;98(6):340–8.

Breseghello F, Sorrells ME. Association mapping of kernel size and milling quality in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars. Genetics. 2006;172(2):1165–77.

Peng JH, Bai Y, Haley SD, Lapitan NL. Microsatellite-based molecular diversity of bread wheat germplasm and association mapping of wheat resistance to the Russian wheat aphid. Genetica. 2009;135(1):95-122.

Wang Z, Wang Y, Hong X, Hu A, Liu D, Yang J, Yang L, Huang YQ, Feng YQ, Gong YQ, Li Y, Fang G, Tang HR, Li YS. Functional inactivation of UDP-N-acetylglucosaminepyrophosphorylase 1 (UAP1) induces early leaf senescence and defence responses in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2015;66(3):973–87.

Zhang XQ, Xue DW, Wu, FB, Zhang GP: Genotypic and environmental variations of Arabinoxylan content and Endoxylanase activity in barley grains. J Integr Agric. 2013;12(8):1489–94.

Yan J, Aznar A, Chalvin C, Birdseye DS, Baidoo EEK, Eudes A, Shih PM, Loqué D, Zhang A, Scheller HV. Increased drought tolerance in plants engineered for low lignin and low xylan content. Biotechnology for Biofuels. 2018;11(1):195.

Li Y, Lu J, Gu GX, Shi ZP, Mao ZG. Studies on water-extractable arabinoxylans during malting and brewing. Food Chem. 2005;93(1):33–8.

Štorchová H, Hrdličková R, Chrtek J, Tetera M, Fitze D, Fehrer J. An improved method of DNA isolation from plants collected in the field and conserved in saturated NaCl/CTAB solution. Taxon. 2000;49(1):79–84.

Douglas SG. A rapid method for the determination of pentosans in wheat flour. Food Chem. 1981;7(2):139–45.

Rouau X, Surget A. A rapid semi-automated method for the determination of total and water-extractable pentosans in wheat flours. Carbohydr Polym. 1994;24(2):123–32.

Sungurtas J, Swanston JS, Davies HV, Mcdougall GJ. Xylan-degrading enzymes and arabinoxylan solubilisation in barley cultivars of differing malting quality. J Cereal Sci. 2004;39(2):273–81.

Miller GL. Use of Dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal Biochem. 1959;31(3):426–8.

Bailey MJ, Biely P, Poutanen K. Interlaboratory testing of methods for assay of xylanase activity. J Biotechnol. 1992;23(3):257–70.

Wang ML, Sukumaran S, Barkley NA, Chen Z, Chen CY, Guo B, Pittman RN, Stalker HT, Holbrook CC, Pederson GA. Population structure and marker-trait association analysis of the US peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) mini-core collection. Theor Appl Genet. 2011;123(8):1307–17.

Hayden MJ, Nguyen TM, Waterman A, Chalmers KJ. Multiplex-ready PCR: a new method for multiplexed SSR and SNP genotyping. BMC Genomics. 2008;9(1):80.

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data, Genetics. 2000;155(2):945–59.

Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics. 2003;164(4):1567–87.

Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software structure: a simulation study. Mol Ecol. 2005;14(8):2611–20.

Hardy OJ. Vekemans X. SPAGeDi: a versatile computer program to analyse spatial genetic structure at the individual or population levels. Mol Ecol Resour. 2002;2(4):618–20.

Kitaura J, Wada K, Nishida M. Molecular phylogeny of Grapsoid and ocypodoid crabs with special reference to the genera Metaplax and Macrophthalmus. J Crustac Biol. 2002;22(3):682–93.

Bradbury PJ, Zhang Z, Kroon DE, Casstevens TM, Ramdoss Y, Buckler ES. TASSEL: software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(19):2633–5.

Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(11):1451-2.

Kota R, Varshney RK, Prasad M, Zhang H, Stein N, Graner A. EST-derived single nucleotide polymorphism markers for assembling genetic and physical maps of the barley genome. Funct Integr Genomics. 2008;8(3):223–33.

Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–4.

Acknowledgements

Barley materials used in this study were provided by Institute of Plant Science and Resources, Okayama University with support in part by the National Bio-Resource Project of the MEXT, Japan. We would like to thank LetPub (www.letpub.com) for providing linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31401316) and Hangzhou Scientific, Technological Program (20140432B03) and State Key Laboratory Breeding Base for Zhejiang Sustainable Pest and Disease Control (No. 2010DS700124-KF1913). The funding bodies had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets supporting the conclusions of this article are available by contacting with the corresponding author (dwxue@hznu.edu.cn or xiaoqinzhang@163.com). The accessions of barley collection are deposited in Hangzhou Normal University and provided on request in form of collaboration.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DX and XZ designed the research, wrote the manuscript and revised the manuscript. XL and YF performed experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. BT, TT, JW and HW performed the molecular experiments. HW, SC, JH, DZ and HX planted and collected the experimental materials. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Table S1. EA activity and TAX content contrast in different regions. (DOCX 15 kb)

Additional file 2:

Figure S1. Identification of EA by association analyses. Manhattan plots in the 210 accessions. and seven SNPs (red points) about HvXYN1 identified in this study with EA activity. The X axis represents the physical position of HvXYN1, and Negative log10-transformed P values are plotted on the vertical axis. (PDF 81 kb)

Additional file 3:

Figure S3. Identification of EA activity and TAX content by association analyses. Quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plots in the 210 accessions. Red points present EA activity and blue points present TAX content. The X axis represents the expected P values and P values are plotted on the vertical axis. (PDF 67 kb)

Additional file 4:

Table S2. The mean value comparison of EA activity and TAX content in different haplotype. (DOCX 16 kb)

Additional file 5:

Table S3. EA activity and TAX content contrast in different superior alleles. (DOCX 15 kb)

Additional file 6:

Figure S2. Identification of TAX content by association analyses. Manhattan plots in the 210 accessions. And three SNPs (red points) about HvXYN1 identified in this study with TAX content. The X axis represents the physical position of HvXYN1, and Negative log10-transformed P values are plotted on the vertical axis. (PDF 76 kb)

Additional file 7:

Table S4. 210 barley accessions from 34 countries. (XLSX 13 kb)

Additional file 8:

Table S5. List of overlapping primers used for the amplificati1on of 1.9 kb nucleotide region of HvXYN1 gene. (DOCX 14 kb)

Additional file 9:

Table S6. 35 SSR markers on 7 chromosomes. (XLSX 12 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, X., Fang, Y., Tian, B. et al. Genetic variation of HvXYN1 associated with endoxylanase activity and TAX content in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). BMC Plant Biol 19, 170 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-019-1747-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-019-1747-5