Abstract

Background

Bacterial ghosts (BGs) are empty bacterial cell envelopes generated by releasing the cellular contents. In this study, a phage infecting Lactobacillus casei ATCC 393 (L. casei 393) was isolated and designated Lcb. We aimed at using L. casei 393 as an antigen delivery system to express phage-derived holin for development of BGs.

Results

A gene fragment encoding holin of Lcb (hocb) was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). We used L. casei 393 as an antigen delivery system to construct the recombinant strain pPG-2-hocb/L. casei 393. Then the recombinants were induced to express hocb. The immunoreactive band corresponding to hocb was observed by western-blotting, demonstrating the efficiency and specificity of hocb expression in recombinants. The measurements of optical density at 600 nm (OD600) after induction showed that expression of hocb can be used to convert L. casei cells into BGs. TEM showed that the cytomembrane and cell walls of hocb expressing cells were partially disrupted, accompanied by the loss of cellular contents, whereas control cells did not show any morphological changes. SEM showed that lysis pores were distributed in the middle or at the poles of the cells. To examine where the plasmid DNA was associated, we analyzed the L. casei ghosts loading SYBR Green I labeled pCI-EGFP by confocal microscopy. The result demonstrated that the DNA interacted with the inside rather than with the outside surface of the BGs. To further analyze where the DNA were loaded, we stained BGs with MitoTracker Green FM and the loaded plasmids were detected using EGFP-specific Cy-3-labeled probes. Z-scan sections through the BGs revealed that pCI-EGFP (red) was located within the BGs (green), but not on the outside. Flow cytometry and qPCR showed that the DNA was loaded onto BGs effectively and stably.

Conclusions

Our study constructed L. casei BGs by a novel method, which may be a promising technology for promoting the further application of DNA vaccine, providing experimental data to aid the development of other Gram-positive BGs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

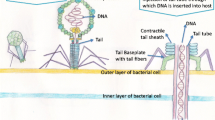

Bacterial ghosts (BGs) are nonliving cell envelopes of bacteria which are generated by lysing the cell walls and releasing the cytoplasmic contents through channels in the cell envelope. BGs are generally produced by expressing the cloned lysis gene E of bacteriophage ΦX174 in Gram-negative bacteria [1]. When the E protein is induced and expressed under suitable conditions, specific transmembrane channels of 40-200 nm form in the bacterial cell walls. Under the influence of osmotic pressure, the cytoplasmic contents are released [2]. E-mediated lysis has been applied in many kinds of Gram-negative bacteria including Escherichia coli [3,4,5], Helicobacter pylori [6, 7], Salmonella enteritidis [8,9,10,11], Salmonella gallinarum [12, 13], Salmonella typhi [14], Edwardsiella tarda [15, 16], Aeromonas hydrophila [17], Vibrio anguillarum [18], Chlamydia trachomatis [19], Yersinia enterocolitica [20], Flavobacterium columnare [21], Haemophilus parasuis [22] and so on.

Since BGs still possess complete antigen structures on the bacterial cell surface [23,24,25], they can be used directly as vaccines. BGs are also good vehicles for loading biomacromolecules such as antigens, drugs, and DNA [26,27,28,29]. Furthermore, BGs are also endowed with intrinsic adjuvant properties as they contain immunostimulating compounds such as peptidoglycan [30]. Another advantage is that the space inside a BG is large, so that multiple epitopes can be presented simultaneously [31,32,33,34]. However, there are still some challenges in preparing BGs. BGs reported till now are all prepared with pathogenic bacteria. The current technology used to prepare BGs cannot lyse 100% of the bacteria. If pathogenic bacteria are used to prepare BGs, there is a risk of infection. Therefore, it is essential to choose a safe bacterial host to develop BG.

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) have been recognized as safe (GRAS) by the American Food and Drug Administration (FDA). For more than 20 years, LAB have been used as potential bacterial carriers to express heterologous proteins in many different fields [35,36,37,38]. Specifically, in immunological research, LAB enables immunization via mucosal routes, which is not only more effective for pathogens, which infect hosts through mucosal routes but is also a simpler method than injection. Many researchers have shown that delivery of antigens via LAB may induce not only mucosal but also systemic immune response [39]. The advantage of LAB in immunoprophylaxis and therapy also depends on their resistance to the low pH of gastric juice, which aids in transit through the stomach to reach the immune sites and induce effective immune responses. Moreover, LAB can adhere to the surface of intestinal epithelium, making the immunostimulation more effective and persistent. Furthermore, the components of LAB have adjuvant properties, which can enhance the immune responses induced by the carried antigen. LAB ghosts can be produced by fermentation in large quantities to save time and labor.

In this study, we developed L. casei ghosts by expressing holin of the L. casei phage. The method is different from the previous methods of producing BGs. Furthermore, LAB are safe and have no infectivity even though they cannot be lysed completely when they are being used to prepare BGs.

Methods

Bacterial strains and plasmids

Lactobacillus secretory expression vector pPG-2 which contains the secretion signal peptide gene sequence (ssUSP) and Lactobacillus casei ATCC 393 were kindly provided by the Netherlands NIZO Institute. L. casei ATCC 393 was cultured anaerobically and statically in MRS (De Man Rogosa Sharpe) medium (Sigma, St, Louis, MO) at 37 °C. The recombinants were cultured in MRS culture medium containing 1% xylose.

Isolation of L. casei phage

In our previous work, a virulent phage against L. casei ATCC 393 was isolated from fermented vegetables and designated as Lcb [40]. The phage Lcb was purified and stored in our laboratory.

Extraction of phage DNA

L. casei ATCC 393 was cultured for 12 h and then was added to 100 mL of MRS-Ca-Mg medium. Phage Lcb was inoculated at a MOI of 0.1 when the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of the culture reached about 0.2. The lysate was centrifuged at 8000×g for 10 min. The supernatant was filtered. Then, the filter liquor was treated with DNaseI and RNase A at a concentration of 1 μg/mL at 37 °C for 1 h. The phages were then concentrated with 1 mol/L NaCl and 10% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 8000 on ice for 1 h, centrifuged at 8000×g for 20 min. The deposit was then resuspended in SM (sodium-magnesium-buffered saline) buffer. Phage DNA was extracted by phenol–chloroform–isoamyl alcohol and then precipitated by isopropanol [40].

Amplification of holin and construction of the expression plasmid

The pPG-2 plasmid was supplied by Jos Seegers (NIZO, The Netherlands), which is an expression vector with an ssUsp signal peptide. Hocb (encoding holin of Lcb) was obtained and amplified from phage Lcb genome by PCR using forward primer 5’-ACCGCTTGAGACGTGAGAATG-3’ and reverse primer 5’ -GCGACTACCAAAGTGATGAGTTTAG -3’. The gene fragment was 481 bp in length. The PCR amplification was performed as follows: 95 °C for 5 min, 30 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 53 °C for 1 min, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s, followed by an extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR product of the Hocb gene was cutted with HindIII and BamHI, then connected to the corresponding site of the pPG2 plasmid digested with BamHI and HindIII to construct the recombinant plasmid (pPG2-Hocb).

Electrotransformation was performed as described previously [38]. Briefly, the ligated plasmid (10 μL) was added into 200 μL of L. casei competent cells, blended gently at 4 °C for 3 min, followed by electroporation (25 μF of 2.5 kV/cm). The mixture was added to MRS broth and then incubated at 37 °C for 2.5 h. The recombinants were screened on MRS-agar medium with 10 μg/mL of chloramphenicol (Cm). The recombinants were identified by sequencing.

Western blot

The recombinants were added to MRS medium with Cm (10 μg/mL) and cultivated at 37 °C for 12 h. Subsequently, the culture was inoculated into MRS medium containing 1% xylose at ratio of 1:10 and cultivated at 37 °C for 36 h. Then the culture was centrifuged at 12000×g for 10 min. The precipitation was followed by washing three times with Tris-Cl (50 mM/L) and lysed with lysozyme (10 mg/mL) at 37 °C for 40 min. The lysates were collected by centrifugation at 10000×g for 10 min and then examined by western blotting to analyze the expression of Hocb protein. The proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane and then blocked with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5% skimmed milk at 37 °C for 3 h. The immunoblots were washed thrice between any two steps. The immunoblots were incubated with 100 μL (1:100 dilution) of mouse anti-Hocb antibodies (prepared in our lab) in PBS. A horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Sigma) was used as a secondary antibody. Detection was developed using the Chemiluminescent Substrate reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Preparation and characterization of BGs

The recombinants were inoculated into 5 mL MRS broth containing 1% xylose (or glucose as a negative control). The cultures were induced at 37 °C and the OD600 was measured after expression at different time periods (0, 8, 16, 24, 32, 40, 48, 56, 64, 72, 80, and 88 h). The morphology of the L. casei BGs was examined by transmission electron microscope (TEM) and scanning electron microscope (SEM) as previously described [12], modified as follows: after lysis, induced and non-induced cells were centrifuged at 4000×g for 10 min and then washed thrice with sterile PBS. The cells were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 2 h at 4 °C and then fixed in 1% aqueous osmium tetroxide. This was followed by serial dehydration in ethanol. Samples were observed by SEM (JSM-5200, JEOL, Japan) after coated with a gold-palladium alloy. To prepare negatively-stained samples for TEM, the L. casei BG suspension was dropped on copper grids. Extra liquid was removed by blotting paper. Then, the morphology of the BGs was examined by TEM (Hitachi Science Systems, Japan).

Preparation of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled linear dsDNA and BGs

The pCI- EGFP (enhanced green fluorescent protein) plasmid (4.7 kb; Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA) was extracted by culture of Escherichia. Coli (E. coli) by the method described previously [41]. RNA and proteins and lipopolysaccharides (LPS) were removed by RNase I digestion and ammonium acetate precipitation. After precipitation with 70% ethanol, the DNA was dissolved in a TE (Tris-Ethylene Diamine Tetraacetic Acid) buffer and stored at − 20 °C. The purity of pCI-EGFP was analyzed by the ratio of OD260/OD280. The plasmids with a ratio of 1.9–1.93 were used to load BGs. Subsequently, pCI-EGFP plasmids were labeled with SYBR Green I. Then, the BGs were resuspended in the DNA solution containing HEPES-buffered saline (HBS) buffer at 25 °C for 10 min and then washed three times with HBS.

To further visualize the localization of the loaded pCI-EGFP plasmids, in situ hybridization was performed. Cy-3-labeled probes were obtained by amplifying EGFP using the oligonucleotides 5’-ATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGA-3’ and 5’- TTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATG-3’. The BGs were dyed with MitoTracker Green FM (0.5 μg /mL) at 37 °C for 1 h and then washed thrice with HBS [41].

Laser scanning confocal microscopy

BGs were labeled with the sulforhodamine B and then loaded with the FITC-labeled linear dsDNA. At the same time some BGs were loaded with the SYBR Green I labeled pCI-EGFP. Both of the BGs were examined respectively at 1000 × magnification by a confocal laser scanning microscope (Axioplan; Zeiss, Vienna, Austria). Sulforhodamine B was excited at 563 nm, FITC at 488 nm, and Cy3 at 543 nm. The sulforhodamine B, FITC fluorescence and Cy3 was detected in the wavelength range of 580–620 nm, 565–590 nm and 650–680 nm respectively. The loaded BGs were examined using the confocal laser scanning microscope by z axis sections with a maximal distance of 0.122 μm. The results of scans were recorded [41].

Quantitative PCR

The BGs loaded with DNA were resuspended in HBS. The BGs loaded with DNA were detected by flow cytometry. The resulting images were analyzed with BD FACSDiva software (USA).

For further quantification, qPCR (quantitative PCR) was performed using SYBR Green I and primers (5’-ATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGA-3’ and 5’- TTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATG-3’) for the holin gene. A standard curve was obtained using ten-fold dilutions of the prepared plasmid and qPCR was performed in duplicate. After loading with the plasmid pCI-EGFP, the BGs were washed five times with HBS. The plasmid DNA in the BGs was extracted and quantified by qPCR.

Results

Western blotting

For the cells grown in MRS broth containing 1% xylose, the immunoreactive band corresponding to hocb was observed at 16 kD by western blotting (Fig. 1, lane 2). The reactive band was not detected in the control group when the cells were grown in MRS broth without 1% xylose (Fig. 1, lane 1). This indicated that hocb protein expression was induced when the recombinants were cultured in MRS medium containing 1% xylose. The result demonstrated the specificity and efficiency and of hocb protein expression in L. casei ATCC 393.

Preparation and characterization of BGs

The OD600 of pPG-2-hocb/L. casei 393 cultures was monitored for a period of 88 h after the addition of xylose (Fig. 2). The OD600 of pPG-2-hocb/L. casei 393 cultures increased during the first 8 h after induction, decreased over next 72 h, and then it remained almost constant until the BGs were collected (Fig. 2). The decline in the OD600 curve after the addition of xylose indicated that L. casei cells were converted into BGs after the expression of the lysis protein.

Growth and lysis curves of pPG-2-hocb/L. casei 393 and pPG-2/L. casei 393 following induction. pPG-2-hocb/L. casei 393 and pPG-2/L. casei 393 were cultured in MRS medium at 37 °C. Expression of the lysis gene hocb was induced with xylose. The optical density (OD600) of the culture was monitored at the indicated time points for a period of 88 h after the addition of xylose. OD600 values are shown in the graph. n = 3; Error bars indicate ± SD

TEM results showed that the cell walls and cytoplasmic membranes of BGs were partially destroyed and the cellular contents were released (Fig. 3b). The control cells did not have any alteration in their morphology and they remained in their distinct forms (Fig. 3a). SEM analysis showed that there were lysis pores present in the envelope of BGs (Fig. 3d) and the lysis pores were distributed mainly in the middle or at the pole of the cells. No changes in morphology were observed for the control cells (Fig. 3c).

Localization of loaded plasmid and linear dsDNA in BGs

To analyze where the DNA was loaded, we examined the L. casei BGs loaded with SYBR Green I labeled pCI-EGFP by confocal microscopy. Green fluorescence was observed in the BGs by confocal microscopy, which confirmed that the SYBR Green I labeled pCI-EGFP was loaded with the inner surface of the BGs. The DNA remained stably associated within the BGs (Fig. 4a and b) after washing three times. This indicated that the DNA interacted with the inside surface of BGs rather than with the outer surface, as DNA entered the BGs only through the lysis tunnels of the cell walls. To further locate the loaded DNA, L. casei ghosts were stained with MitoTracker Green FM. The plasmids loaded were then detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization. The result of scans by the confocal laser scanning microscope revealed that pCI-EGFP (red) was located inside of the BGs (green) (Fig. 4c, d, e). These results further confirmed the results obtained with the SYBR Green I labeled pCI-EGFP.

Localization of loaded DNA in L. Casei ghosts visualized by confocal laser scanning microscopy. a L. casei 393 ghosts filled with SYBR Green I labeled pCI-EGFP under white light. b L. casei ghosts filled with SYBR Green I labeled pCI-EGFP. Overlay of differential interference contrast and fluorescent image. The image indicated that the plasmid was filled within the bacterial ghosts. c Ghost membranes were stained with MitoTracker Green FM (green). d pCI-EGFP was detected by in situ hybridization with Cy3-labeled probes (red) specific for the EGFP. e All fluorescence photomicrographs (c, d) were taken of one middle z-scan section through the middle plane of the loaded bacterial ghosts and subsequently overlaid (e). Direct overlays of red and green fluorescent structures are represented by the yellow color

Quantification of BG-loaded DNA

The efficiency of BGs to load DNA was examined by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 5, the average fluorescence intensity of loaded BGs shifted distinctly compared with that of unloaded BGs. This indicated that DNA had been loaded in the BGs effectively. Results of qPCR showed that the maximum load is 230.9 μg of pCI-EGFP/mg BGs (Fig. 6). The loading capacity of BGs still reached 44.6 μg/mg after washing three times. Taken together, these results show that DNA can be loaded in BGs effectively and stably.

Determination of DNA loaded in the BGs by qPCR. L. casei 393 ghosts were loaded with pCI-EGFP plasmid. BGs were washed five times with HBS after loading with pCI-EGFP. DNA in bacterial ghosts and washing solution were extracted respectively and quantified by qPCR. Each point was the mean of quadruplicate measurements ± SD. Each experiment was repeated at least twice

Discussion

BGs are empty bacterial cell envelopes created by releasing the cytoplasmic contents through pores in the cell walls. Because BGs retained their original cell shape and surface structures, much of their immunogenicity is retained. If BGs are used as a carrier system to deliver DNA vaccines and drugs to prevent and cure diseases, they will have great application potential. Typically, BGs are prepared by expressing the E gene of phage PhiX174 cloned in bacteria [23]. So far, the dissolution mediated by E protein has been used in many Gram negative bacteria. However, because the cell wall structure of Gram positive bacteria is different from that of Gram negative bacteria, the expression of E gene can not lyse the gram-positive bacteria but kill them. As such, this method cannot be used to develop Gram positive BGs.

In this study, we used L. casei to construct BGs by expressing the lysis protein of L. casei phage. TEM and SEM analysis showed that we succeeded in preparing L. casei BGs using this novel method. TEM analysis showed that there was large space inside of the BGs, which could be loaded with biomacromolecules such as DNA, proteins, and drugs. Up until now, all BGs reported have been created from pathogenic bacteria and research regarding LAB BGs has not been reported. Our study is the first to develop L. casei BGs. This method to prepare L. casei BGs is different from previous methods reported, which provides experimental data and reference for developing other Gram positive BGs.

The development of DNA vaccines is a major breakthrough in the vaccinology field. DNA vaccines have many advantages compared with traditional vaccines. However, uptake of DNA is difficult because it is easily degraded, and its poor immunogenicity hampers its application [42]. Improving the immune response of DNA vaccines is a key factor in determining immune effect, which is of great significance in theoretical research and production practice. DNA can combine with the inner membrane of BGs non-specifically. Many studies have confirmed that BGs have a strong capacity for loading DNA. BGs not only target the DNA vaccine to antigen presenting cells (APCs), but also act as adjuvants to promote activation and maturation of dendritic cells. HIV gp140 DNA vaccine loaded by Salmonella typhi Ty21a BGs were readily taken up by murine macrophage cells so that gp140 could be efficiently expressed. Specific antibody responses in mice immunized with BG-delivered DNA vaccines were significantly higher than those in mice vaccinated with naked DNA [42]. Wen et al. reported that Mannheimia haemolytica BGs were used as carrier to deliver DNA vaccines [14]. In vitro studies demonstrated that one BG could load 2000 copies of plasmid (5 μg DNA/mg BG). Furthermore, vaccination studies demonstrated that more efficient immune responses were stimulated by BG-delivered DNA vaccines than naked DNA. In our study, the results of qPCR showed that the maximum load was 230.9 μg of pCI-EGFP/mg BG. The size of L. casei is bigger, therefore the space inside of L. casei BG is larger and thus, L. casei BGs have stronger capacity to load DNA. Furthermore, L. casei BGs are safer than BGs made from pathogenic bacteria even if they cannot be lysed completely. L. casei BGs may be used to solve the issues surrounding DNA vaccines, such as poor immunogenicity and high degradability, and improve the level of immune response elicited by them.

Conclusions

Our study is the first to develop L. casei BGs using a novel method, which may be a promising method for developing effective carriers for DNA vaccines. L. casei BGs could load DNA effectively and the loaded DNA was connected with the inside of the BGs stably. Our study provides some experimental data and reference for the development of other Gram positive BGs. Furthermore, protein, DNA and drugs can all be loaded in BGs, which offers innovative methods for the design and development of novel vaccines to prevent and treat diseases.

Abbreviations

- APCs:

-

Antigen presenting cells

- BGs:

-

Bacterial ghosts

- Cm:

-

Chloramphenicol

- E. coli :

-

Escherichia. Coli

- EGFP:

-

Enhanced green fluorescent protein

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- FITC:

-

Fluorescein isothiocyanate

- GRAS:

-

Generally regarded as safe

- HBS:

-

Hepes-buffered saline

- HRP:

-

Horseradish peroxidase

- HRP:

-

Horseradish peroxidase

- L. casei 393:

-

Lactobacillus casei ATCC 393

- lab:

-

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB)

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- MRS:

-

De Man Rogosa Sharpe

- OD600 :

-

Optical density at 600 nm

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- qPCR:

-

Auantitative polymerase chain reaction

- SEM:

-

Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

- SM:

-

Sodium-magnesium-buffered saline

- ssUSP:

-

Secretion signal peptide gene sequence

- TE:

-

Tris-Ethylene Diamine Tetraacetic Acid

- TEM:

-

Transmission electron microscope

References

Witte A, Wanner G, Sulzner M, Lubitz W. Dynamics of PhiX174 protein Emediated lysis of Escherichia coli. Arch Microbiol. 1992;157:381.

Szosta MP, Hensel A, Eko FO, Klein R, Auer T, Mader H. Bacterial ghosts: nonliving candidate vaccines. J Biotechnol. 1996;44:161–70.

Vilte DA, Larzábal M, Mayr UB, Garbaccio S, Gammella M, Rabinovitz BC, Delgado F, Meikle V, Cantet RJ, Lubitz P, Lubitz W, Cataldi A, Mercado EC. A systemic vaccine based on Escherichia coli O157:H7 bacterial ghosts (BGs) reduces the excretion of E. coli O157:H7 in calves. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2012;146:169–76.

Cai K, Gao X, Li T, Hou X, Wang Q, Liu H, Xiao L, Tu W, Liu Y, Shi J, Wang H. Intragastric immunization of mice with enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 bacterial ghosts reduces mortality and shedding and induces a Th2-type dominated mixed immune response. J Microbiol. 2010;56:389–98.

Mayr UB, Haller C, Haidinger W, Atrasheuskaya A, Bukin E, Lubitz W, Ignatyev G. Bacterial ghosts as an oral vaccine:a single dose of Escherichia coli O157:H7 bacterial ghosts protects mice against lethal challenge. Infect Immun. 2005;73:4810–7.

Talebkhan Y, Bababeik M, Esmaeili M, Oghalaei A, Saberi S, Karimi Z, Afkhami N, Mohammadi M. Helicobacter pylori bacterial ghost containing recombinant Omp18 as a putative vaccine. J Microbiol Methods. 2010;82:334–7.

Chen J, Li N, She F. Helicobacter pylori outer inflammatory protein DNA vaccine-loaded bacterial ghost enhances immune protective efficacy in C57BL/6 mice. Vaccine. 2014;32:6054–60.

Chetan V, John J, Lee H. Development of a biosafety enhanced and immunogenic Salmonella Enteritidis ghost using an antibiotic resistance gene free plasmid carrying a bacteriophage lysis system. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78193.

Peng W, Si W, Yin L, Liu H, Yu S, Liu S, Wang C, Chang Y, Zhang Z, Hu S, Du Y. Salmonella enteritidis ghost vaccine induces effective protection against lethal challenge in specific-pathogen-free chicks. Immunobiology. 2011;216:558–65.

Jawale CV, Lee JH. Salmonella enterica Serovar Enteritidis ghosts carrying the Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin B subunit are capable of inducing enhanced protective immune responses. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2014;21:799–807.

Jawale CV, Lee JH. An immunogenic Salmonella ghost confers protection against internal organ colonization and egg contamination. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2014;162:41–50.

Chaudhari AA, Jawale CV, Kim SW, Lee JH. Construction of a Salmonella Gallinarum ghost as a novel inactivated vaccine candidate and its protective efficacy against fowl typhoid in chickens. Vet Res. 2012;43:44–51.

Jawale CV, Chaudhari AA, Lee JH. Generation of a safety enhanced Salmonella Gallinarum ghost using antibiotic resistance free plasmid and its potential as an effective inactivated vaccine candidate against fowl typhoid. Vaccine. 2014;32:1093–9.

Wen J, Yang Y, Zhao G, Tong S, Yu H, Jin X, Du L, Jiang S, Kou Z, Zhou Y. Salmonella typhi Ty21a bacterial ghost vector augments HIV-1 gp140 DNA vaccine-induced peripheral and mucosal antibody responses via TLR4 pathway. Vaccine. 2012;30:5733–9.

Choi SH, Nam YK, Kim KH. Novel expression system for combined vaccine production in Edwardsiella tarda ghost and cadaver cells. Mol Biotechnol. 2010;46:127–33.

Wang X, Lu C. Mice orally vaccinate d with Edwardsiella tarda ghosts are significantly protected against infection. Vaccine. 2009;27:1571–8.

Tu FP, Chu WH, Zhuang XY, Lu CP. Effect of oral immunization with Aeromonas hydrophila ghosts on protection against experimental fish infection. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2010;50:13–7.

Kwon SR, Kang YJ, Lee DJ, Lee EH, Nam YK, Kim SK, Kim KH. Generation of Vibrio anguillarum ghost by Coexpression of PhiX 174 lysis E gene and staphylococcal nuclease a gene. Mol Biotechnol. 2009;42:154–9.

Eko FO, Talin BA, Lubitz W. Development of a Chlamydia trachomatis bacterial ghost vaccine to fight human blindness. Human Vaccines. 2008;4:176–83.

Cai K, Zhang Y, Yang B, Chen S. Yersinia enterocolitica ghost with msbB mutation provides protection and reduces proinflammatory cytokines in mice. Vaccine. 2013;31:334–40.

Zhu W, Yang G, Zhang Y, Yuan J, An L. Generation of biotechnology-derived Flavobacterium columnare ghosts by PhiX174 gene E-mediated inactivation and the potential as vaccine candidates against infection in grass carp. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:1–8.

Hu M, Zhang Y, Xie F, Li G, Li J, Si W, Liu S, Hu S, Zhang Z, Shen N, Wang C. Protection of piglets by a Haemophilus parasuis ghost vaccine against homologous challenge. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2013;20:795–802.

Langemann T, Koller VJ, Muhammad A, Kudela P, Mayr UB, Lubitz W. The bacterial ghost platform system: production and applications. Bioeng Bugs. 2010;1:326–36.

Kudela P, Koller VJ, Lubitz W. Bacterial ghosts (BGs)–advanced antigen and drug delivery system. Vaccine. 2010;28:5760–7.

Riedmann EM, Kyd JM, Cripps AW, Lubitz W. Bacterial ghosts as adjuvant particles. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2007;6:241–53.

Lubitz W. Bacterial ghosts as carrier and targeting systems. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2001;1:765–71.

Jalava K, Eko FO, Riedmann E, Lubitz W. Bacterial ghosts as carrier and targeting systems for mucosal antigen delivery. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2003;2:45–51.

Mayr UB, Walcher P, Azimpour C, Riedmann E, Haller C, Lubitz W. Bacterial ghosts as antigen delivery vehicles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57:1381–91.

Muhammad A, Champeimont J, Mayr UB, Lubitz W, Kudela P. Bacterial ghosts as carriers of protein subunit and DNA-encoded antigens for vaccine applications. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2012;11:97–116.

Paukner S, Stiedl T, Kudela P, Bizik J, A Laham F, Lubitz, W. Bacterial ghosts as a novel advanced targeting system for drug and DNA delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2006; 3:11–22.

Walcher P, Mayr UB, Azimpour-Tabrizi C, Eko FO, Jechlinger W, Mayrhofer P, Alefantis T, Mujer CV, DelVecchio VG, Lubitz W. Antigen discovery and delivery of subunit vaccines by nonliving bacterial ghost vectors. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2004;3:681–91.

Eko FO, Witte A, Huter V, Kuen B, Fürst-Ladani S, Haslberger A, Katinger A, Hensel A, Szostak MP, Resch S, Mader H, Raza P, Brand E, Marchart J, Jechlinger W, Haidinger W, Lubitz W. New strategies for combination vaccines based on the extended recombinant bacterial ghost system. Vaccine. 1999;17:1643–9.

Eko FO, He Q, Brown T, McMillan L, Ifere GO, Ananaba GA, Lyn D, Lubitz W, Kellar KL, Black CM, Igietseme JU. A novel recombinant multisubunit vaccine against Chlamydia. J Immunol. 2004;173:3375–82.

Khan AS, Mujer CV, Alefantis TG, Connolly JP, Mayr UB, Walcher P, Lubitz W, Delvecchio VG. Proteomics and bioinformatics strategies to design countermeasures against infectious threat agents. J Chem Inf Model. 2006;46:111–5.

Cortes-Perez NG, Bermudez-Humaran LG, Le Loir Y, RodriguezPadilla C, Gruss A, Saucedo-Cardenas O, Langella P, Montes-deOca-Luna R. Mice immunization with live lactococci displaying a surface anchored HPV-16 E7 oncoprotein. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;229:37–42.

Fredriksen L, Mathiesen G, Sioud M, Eijsink VG. Cell wall anchoring of the 37-kilodalton oncofetal antigen by Lactobacillus plantarum for mucosal cancer vaccine delivery. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:7359–62.

Jiang X, Yu M, Qiao X, Liu M, Tang L, Jiang Y, Cui W, Li Y. Up-regulation of MDP and tuftsin gene expression in Th1 and Th17 cells as an adjuvant for an oral Lactobacillus casei vaccine against anti-transmissible gastroenteritis virus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:8301–12.

Qiao X, Li G, Wang X, Li X, Liu M, Li Y. Recombinant porcine rotavirus VP4 and VP4-LTB expressed in Lactobacillus casei induced mucosal and systemic antibody responses in mice. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:249.

Bermudez-Humaran LG, Kharrat P, Chatel JM, Langella P. Lactococci and lactobacilli as mucosal delivery vectors for therapeutic proteins and DNA vaccines. Microb Cell Factories. 2011;10(Suppl 1):S4.

Zhang X, Lan Y, Jiao W, Li Y, Tang L, Jiang Y, Cui W, Qiao X. Solation and characterization of a novel virulent phage of Lactobacillus casei ATCC 393. Food Environ Virol. 2015;7:333–41.

Paukner S, Kudela P, Kohl G, Schlapp T, Friedrichs S, Lubitz W. DNA-loaded bacterial ghosts efficiently mediate reporter gene transfer and expression in macrophages. Mol Ther. 2005;11:215–23.

Ebensen T, Paukner S, Link C, Kudela P, de Domenico C, Lubitz W, Guzmán CA. Bacterial ghosts are an efficient delivery system for DNA vaccines. J Immunol. 2004;172:6858–65.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jos Seegers (NIZO, The Netherlands) for supplying the pPG612.1 plasmid.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National key research and development plan project (No. 2016YFD0500904), the Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province (C2016028), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (No. 31302127) and Fund of Heilongjiang Province Education Department (12541003). The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RH, ML and TT performed the experiments. RW, LW, YJ and WC performed the statistical analysis. XQ, YL, YX, LT and ML conceived the project. XQ are the grant holders and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. (This manuscripts reporting study does not involve human participants, human data or human tissue.)

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, R., Li, M., Tang, T. et al. Construction of Lactobacillus casei ghosts by Holin-mediated inactivation and the potential as a safe and effective vehicle for the delivery of DNA vaccines. BMC Microbiol 18, 80 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-018-1216-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-018-1216-6