Abstract

Background

Jute (Corchorus spp.), belonging to the Malvaceae family, is an important natural fiber crop, second only to cotton, and a multipurpose economic crop. Corchorus capsularis L. is one of the only two commercially cultivated species of jute. Gene expression is spatiotemporal and is influenced by many factors. Therefore, to understand the molecular mechanisms of tissue development, it is necessary to study tissue-specific gene expression and regulation. We used weighted gene coexpression network analysis, to predict the functional roles of gene coexpression modules and individual genes, including those underlying the development of different tissue types. Although several transcriptome studies have been conducted on C. capsularis, there have not yet been any systematic and comprehensive transcriptome analyses for this species.

Results

There was significant variation in gene expression between plant tissues. Comparative transcriptome analysis and weighted gene coexpression network analysis were performed for different C. capsularis tissues at different developmental stages. We identified numerous tissue-specific differentially expressed genes for each tissue, and 12 coexpression modules, comprising 126 to 4203 genes, associated with the development of various tissues. There was high consistency between the genes in modules related to tissues, and the candidate upregulated genes for each tissue. Further, a gene network including 21 genes directly regulated by transcription factor OMO55970.1 was discovered. Some of the genes, such as OMO55970.1, OMO51203.1, OMO50871.1, and OMO87663.1, directly involved in the development of stem bast tissue.

Conclusion

We identified genes that were differentially expressed between tissues of the same developmental stage. Some genes were consistently up- or downregulated, depending on the developmental stage of each tissue. Further, we identified numerous coexpression modules and genes associated with the development of various tissues. These findings elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the development of each tissue, and will promote multipurpose molecular breeding in jute and other fiber crops.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Jute (Corchorus spp.), belonging to the Malvaceae family, is an important natural fiber crop, second only to cotton [1]. Among more than 50 Corchorus species [2], only two (C. capsularis L. and C. olitorius L.) are grown commercially in subtropical and tropical regions [3]. Jute fibers have advantages such as good moisture absorption, fast water dispersion, corrosion resistance, and are mainly used in the textile industry to make clothes, decorations, packaging materials, and other products [3, 4]. Jute is a multipurpose economic crop, and each tissue has its particular usage. For example, jute stalks can be used to make paper and to provide fuel, activated carbon, environmental protection materials, and building composite materials [3]. The leaves can be used as green vegetables and animal feed, and to produce skin care products and herbal medicine [5]. The seeds can be used to extract industrial oil and other products [6]. The versatility of jute in the marketplace will continue to expand, especially in environmental protection, vegetable production, and facial mask manufacturing [7]. These many benefits derive from the different chemical, physical, and biological properties of its various tissues, which are under tissue-specific gene expression control.

Understanding the expression and regulation of genes in different tissues will help us to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the development of these tissues [8]. With the rapid development of high-throughput sequencing technology and bioinformatics, tissue-specific gene expression and regulation analyses have been carried out on many crops [9,10,11]. In particular, weighted gene coexpression network analysis (WGCNA) has recently been widely used to predict the functional roles of gene coexpression modules and individual genes underlying the differences between tissues [12,13,14]. For example, WGCNA or comparative transcriptomic analysis revealed coexpression modules and dynamics in gene expression involved in stress response [12], seed development [13], and floral bud development [14] in various tissues of crop plants, etc.. WGCNA has become a fascinating integrated and systematic genome-wide approach, focusing on elucidating biological networks and gene function [15]. Recently, high-throughput sequencing technology has greatly promoted the study of jute molecular biology and genetics. For C. capsularis, many molecular markers including single nucleotide polymorphisms and simple sequence repeats have been developed through high-throughput sequencing [4, 16,17,18]. Several transcriptome studies have been reported in C. capsularis. These uncovered numerous differentially expressed unigenes involved in vegetative growth and development [19], abiotic stress [20] and bast fiber development [21]. However, a systematic and comprehensive transcriptome analysis has not yet been reported for C. capsularis.

In this study, we performed a transcriptome analysis of different C. capsularis tissues in two different developmental stages. Our objective was to understand the molecular mechanisms underpinning the development of different tissue types, and to promote multipurpose molecular breeding in jute and other fiber crops.

Results

Transcriptome sequencing

We sequenced 19 RNA samples from jute (Yueyuan5hao) stem bast, leaf, fruit, and flower tissues during differential developmental stages. A total of 943.45 million high-quality reads were generated. Because jute flowers are very small, many flowers were required in order to obtain enough RNA for sequencing studies. Therefore, we combined many flowers for sequencing, whereas the other tissues were sequenced using three biological replicates. The smallest amount of sequencing data was obtained for flower tissue (54.22 million clean reads). We obtained clean reads for all other tissues, ranging from 145.26 to 152.42 million reads. We mapped the clean reads to the C. capsularis reference genome (CCACVL1_1.0); most clean reads from each tissue (> 92.45%) were aligned uniquely to the reference genome (Table 1).

Global transcriptome analysis of jute

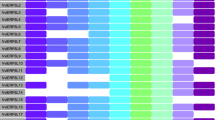

To assess the number of genes expressed in the various tissue types at different stages, we analyzed the reads per kilobase of exon model per million reads (RPKM) of all 29,605 genes identified in this study. An RPKM value greater than one was set as the criteria for gene expression. In stem bast tissues, there was transcriptional activity for 18,320 and 18,268 genes, during the vegetative growth period (“bast tissue during the vegetative growth period”, BVGP) and flowering period (“bast tissue during the flowering period”, BFP), respectively (Additional files 1 and 2: Tables S1–2); in leaf tissues, 17,480 and 18,126 genes were expressed in these two stages, respectively (Additional files 3 and 4: Tables S3–4). During the flowering period, fruits were categorized into two developmental stages (diameter < 0.8 cm, hereafter “FF1”; or diameter > 0.8 cm, hereafter “FF2”), and were used for RNA sequencing; 19,396 and 19,509 genes, respectively, were expressed in these developmental stages (Additional files 5 and 6: Tables S5–6). Furthermore, 17,842 expressed genes (Additional file 7: Table S7) were identified in flowers. In total, 14,943 genes (Additional file 8: Table S8) were expressed across all tissues during the vegetative growth period and flowering period. Differences in gene expression between tissues were visualized using hierarchical cluster analysis based on the RPKM values of the 29,605 genes (Fig. 1).

Hierarchical cluster analysis of the jute genes that we analyzed. The analysis is based on reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (RPKM). MF, mature flowers; LVGP, leaf tissues of vegetative growth period; LFP, leaf tissues of flowering period; FT1, Fruits < 0.8 cm in diameter; FT2, Fruits > 0.8 cm in diameter; BVGP, bast of vegetative growth period; BFP, bast of flowering period

Comparative transcriptome analysis of the different tissues and developmental stages

We identified the candidate differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for each tissue by comparison with other tissues at the same developmental stage. Relative to leaf tissues (“leaf tissues during the vegetative growth period”, LVGP), we identified 2035 upregulated and 2231 downregulated genes in BVGP (Additional files 9 and 10: Tables S9–10). In FF1, there were 7108 upregulated and 6059 downregulated genes, relative to BFP; 7782 upregulated and 7074 downregulated genes, relative to leaf tissues during the flowering period (LFP); 281 upregulated and 1438 downregulated genes, relative to flowers; and 192 upregulated and 219 downregulated genes, relative to all other tissue types (Fig. 2a and b). In FF2, there were 5988 upregulated and 5067 downregulated genes, relative to BFP; 6897 upregulated and 6272 downregulated genes, relative to LFP; 256 upregulated and 1376 downregulated genes, relative to flowers; and 210 upregulated and 181 downregulated genes, relative to all other tissue types (Fig. 2c, d). In total, 94 upregulated and 133 downregulated genes were identified in fruit during the FF1 and FF2 developmental stages (Fig. 2e and f). In BFP, we identified 6059 upregulated and 7108 downregulated genes, relative to FF1; 5067 upregulated and 5988 downregulated genes, relative to FF2; 5328 upregulated and 5896 downregulated genes, relative to LFP; and 261 upregulated and 1648 downregulated genes, relative to flowers. In total, 103 upregulated and 184 downregulated genes were identified in stem bastduring the vegetative growth period and flowering period (Fig. 2g and h). In total, 275 upregulated and 207 downregulated genes were identified by comparing leaf tissues with other organ tissues during the vegetative growth period and flowering period (Fig. 2i and j). The fewest DEGs (< 3000 in total) were found in flower tissues relative to other tissues (Fig. 2k and l).

Venn diagram of differential gene expression between various jute tissues. a-d Upregulated (a and c) and downregulated (b and d) genes in fruit tissues (FF1 and FF2) compared with other tissues at each developmental stage. e, f Genes identified as upregulated (e) and downregulated (e) in fruit tissue (FF1 and FF2) compared with all other tissues at each developmental stage. g, h Upregulated (g) and downregulated (h) genes in stem bast tissues compared with other tissues of the same developmental stage. i, j Upregulated (i) and downregulated (j) genes in leaf tissues compared with other tissues at the same developmental stage. k, l Upregulated and downregulated genes in flower tissues compared with other tissues at the same stage. MF, mature flowers; LVGP, leaf tissues of vegetative growth period; LFP, leaf tissues of flowering period; FT1, fruits < 0.8 cm in diameter; FT2, fruits > 0.8 cm in diameter; BVGP, bast of vegetative growth period; BFP, bast of flowering period

Identification of gene coexpression modules

To identify genes and coexpression modules with similar expression profiles related to the development of different tissues, we carried out a WGCNA. To avoid spurious results, low-expression genes (average RPKM< 1) were excluded. In total, 20,012 genes were used in this analysis, and 12 coexpression modules comprising 126 to 4203 genes were identified; and there is a higher correlation among genes in modules (Fig. 3). Further, we investigated the associations between each module and each tissue at different developmental stages, using correlation analysis. Only one module was related to LFP (related module: blue), FF1 (related module: turquoise), and BFP (related module: brown); two modules were related to BVGP (related module: pink and purple), FF2 (related module: turquoise and magenta), LVGP (related module: black and greenyellow), and flowers (related module: greenyellow and red) (Fig. 4a). The turquoise module correlated with both FF1 and FF2. By comparing the genes in the modules related to particular traits to the candidate upregulated genes for each tissue type (defined as comparison group), we found that the candidate upregulated genes and the genes in each module were highly consistent for each comparison group. The ratio of overlapping genes between each comparison group was greater than 20% for almost all combinations, except the combination of flowers and the greenyellow module (2%) (Fig. 4b).

The twelve coexpression modules, comprising 126 to 4203 jute genes. The modules were identified using weighted gene coexpression network analysis (WGCNA). The heatmap depicted adjacencies or topological overlaps, with light colors denoting higher adjacency (correlation), with red colors denoting low adjacency (correlation). The gene dendrograms and module colors are plotted along the top and left side of the heatmap. Each color represents a module

Coexpression module and gene comparison analyses. We compared the genes in modules related to traits to the candidate upregulated genes. a Correlations between the modules and tissues at two different developmental stages. b Overlap between genes in modules related to traits and candidate upregulated genes. MF, mature flowers; LVGP, leaf tissues of vegetative growth period; LFP, leaf tissues of flowering period; FT1, fruits < 0.8 cm in diameter; FT2, fruits > 0.8 cm in diameter; BVGP, bast of vegetative growth period; BFP, bast of flowering period

We performed Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis for the overlapping genes for each comparison group. The terms ‘protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum’, ‘sesquiterpenoid and triterpenoid biosynthesis’, ‘plant hormone signal transduction’, and ‘glycolysis/gluconeogenesis’, were enriched in stem bast tissues. In addition to other terms, the terms ‘phenylpropanoid biosynthesis’, ‘biosynthesis of secondary metabolites’, and ‘flavonoid biosynthesis’ were enriched in the fruit; ‘pentose and glucuronate interconversions’ and ‘phenylalanine metabolism’ were enriched in the flowers; and ‘metabolic pathways’ and ‘photosynthesis’ were enriched in the leaf tissues (Additional files 11 and 12: Fig. S1–2).

Identification of genes in coexpression modules associated with fiber tissues

The vegetative growth period is the period of jute fiber development and rapid thickening of stem bast. Based on the WGCNA results, the pink module related with BVGP. We evaluated the correlation between the expression of genes and stem bast tissues, and define this value as the Gene Significance (GS) score. We also assessed the correlation of the pink module with the gene expression profiles, based on this correlation, we defined module membership (MM) in the pink module. GS and MM were closely correlated (cor = 0.85, p < 1e− 200) in the pink module for stem bast tissue (Fig. 5), reflecting the strong correlation between stem bast tissue and the pink module genes. We identified 253 upregulated genes in stem bast that also occurred within the pink module, during the vegetative growth period. We further analyzed and constructed a coexpression network for these genes. We focused on a transcription factor gene (OMO55970.1), which was directly linked to 21 other genes (Fig. 6). Fourteen of these genes were included among the 253 common genes (Table 2). Some of these 14 genes were involved in the development of stem bast and fiber, with very high GS.BVGP, and MM.pink values. For example, OMO50871.1 is an epidermal patterning factor, OMO51203.1 is related to glucose metabolism, and OMO87663.1 is a wall-associated receptor kinase.

Validation of the differential gene expression results

To validate the RNA-seq results, qRT-PCR analysis was performed for 12 genes during the vegetative growth period. The genes showed differential expression when comparing stem bast with leaf tissue, consistent with the results obtained by the RNA-seq analysis (Additional file 13: Fig. S3). In addition, we compared DEGs identified in bast tissue during the vegetative growth period in our study with the DEGs identified in fibre cells which were included in bast tissue by comparing fibre cells with seedling reported by Islam et al. A total of 714 upregulated and 837 downregulated genes were discovered in the both studies (Additional files 14 and 15: Tables S11–12), accounting for approximately 35% (714/2035) and 38% (837/2231) of upregulated and downregulated genes identified in bast tissue during the vegetative growth period in our study.

Discussion

Knowing how genes are expressed and regulated in various tissues is the basis of studying gene function, and is required for molecular breeding. The study of gene expression profiles of various tissues during different developmental stages has been reported for many crops [22, 23]. However, a systematic and comprehensive transcriptome has not yet been reported for C. capsularis, and transcription information for various tissues is lacking. In the study, we compared the transcriptomes of four tissue types during two growth stages, revealing many genes and marked distinctions in gene expression. Tissues were clustered together according to their gene expression signatures, consistent with previous reports [23, 24].

Comparative transcriptome analysis is a useful and conventional method for investigating spatiotemporal pattern of gene expression [23, 25,26,27]. However, it is difficult to examine the relationships between DEGs and tissues using differential gene expression analysis. Therefore, the systematic analytical methods are called for comprehensively extracting information from transcriptome data. WGCNA is a popular and useful approach for revealing meaningful relationships between gene modules and biological processes, and between genes and traits [13, 14]. In this study, we first identified the genes that were differentially expressed in each tissue compared with other tissues in the same developmental period, then identified the genes that were consistently up- or down regulated in different periods for each tissue. These findings will help us to understand the development of different tissues. In particular, genes that are consistently up- and downregulated might play crucial roles in the metabolism, growth, and development of each tissue; these should be the focus of future studies.

We then identified 12 coexpression modules comprising 126 to 4203 genes, that were associated with the development of various tissues, using WGCNA. We compared the genes in modules related to tissues, to the candidate upregulated genes in each tissue, and found that they were highly consistent (Fig. 4b). This corroborated our analysis of the correlation between the coexpression modules and the gene expression profiles of each tissue. Furthermore, the KEGG analysis for the overlapping genes for each comparison group showed that the various tissue types have different enrichment pathways. This provides evidence that the genes that code for the pathways have variable spatiotemporal pattern of expression in the tissues. Some similar results have been found in previous studies on jute pathway enrichment, for example, ‘glycolysis/gluconeogenesis’ was enriched in stem bast tissue, which associated with bast fibre synthesis [19, 28];

We verified that the WGCNA was suitable for the analysis of gene expression modules in the various tissues that we studied. Additionally, 253 genes that were upregulated in stem bast also occurred within the pink module, during the vegetative growth period. Among these genes, transcription factor OMO55970.1 was directly linked to 21 other genes, some of them showing very high GS.BVGP and MM.pink correlation and directly involved in the development of stem bast and fiber according to gene annotation [28]. In particular, OMO55970.1, a TGA1 transcription factor, is a candidate transcription factor for fiber differentiation [29]. OMO50871.1 is an epidermal patterning factor; OMO51203.1 is related to glucose metabolism; and OMO87663.1 is a wall-associated receptor kinase which play a crucial role in correct cell-wall synthesis [30]. Our results suggest that these genes are of great significance for the formation of stem bast and fiber, and that they should be the focus of future research.

Conclusion

This is the first systematic and comprehensive transcriptome analysis for Corchorus capsularis. To describe the transcriptomes associated with various tissue types and developmental stages, we performed a comparative transcriptome and coexpression modules analysis. We compared the genes in modules related to tissues to the candidate upregulated genes for each tissue, and found that they were highly consistent. These results constituted a systematic and complete database of gene expression of jute various tissue types and tissue development. We identified a gene network of 21 genes that was directly regulated by transcription factor OMO55970.1. Some of these genes, such as OMO55970.1, OMO51203.1, OMO50871.1, and OMO87663.1, were immediately involved in the development of stem bast and fiber. These genes should be the focus of future research. In summary, these findings help to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of tissue development in jute, and to promote multipurpose molecular breeding in jute and other fiber crops.

Methods

Plant growth and transcriptome sequencing

The C. capsularis used in this study was a variety (Yueyuan5hao). It originally came from Guangdong Province, China, and stored in the National Bast Fiber Germplasm Middle-term Storage of China (our lab, in Changsha, Hunan province, China). In total, 20 plants were planted in a well-ventilated greenhouse, in 10 pots with two plants per pot. During the entire growth period, the environmental conditions of the soil and fertilizer in each pot were kept consistent, to ensure minimal differences in plant growth. When the plants had grown to approximately 1 m (vegetative growth period), stem bast and leaf tissues were collected for RNA extraction. During the flowering and fruiting period, tissues including leaves, stem bast, fruits with diameter < 0.8 cm, fruits with diameter > 0.8 cm, and flowers were collected for RNA extraction. Three replicates of each tissue were collected, except of flowers. Owing to the small size of the flowers, we sampled enough amount for mixed sequencing. Total RNA was extracted from 19 tissue samples using Trizol (Invitrogen, Santa Clara, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA quality assessment and construction of sequencing libraries were performed according to Yang et al. [31]. In total, 19 sequencing libraries were generated, using NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, USA). RNA sequencing was carried out on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 System.

Read mapping and differential gene expression analysis

Firstly, raw reads were processed in Perl using in-house scripts, to obtain clean, high quality reads by removing adapter sequences and low-quality reads. All downstream analyses were performed using the clean reads. We downloaded the reference genome of C. capsularis (CCACVL1_1.0) from the NCBI database [28]. We then used Bowtie v2.0.6 [32] to build the reference genome index, TopHat v2.0.9 [33] to map clean reads to the reference genome, and HTSeq v0.6.1 to count the number of reads aligned to each gene [34]. To calculate gene expression levels, we assessed the RPKM of each gene based on the number of reads mapped to the gene and the length of the gene. Finally, differential gene expression analysis was performed using a model based on the negative binomial distribution, using the R package DESeq (1.10.1) [35]. Genes with an adjusted P-value < 0.05 were considered to be differentially expressed. P-values were adjusted to reduce the false discovery rate using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure [35].

Identification of gene coexpression modules

To identify gene clusters associated with various tissue types, we performed a WGCNA using the R package WGCNA [36], using RPKM values from the 19 tissue samples. First, we clustered all samples to exclude any obvious outliers (cutHeight = 3000). We then performed network construction and module detection using an automatic 1-step network construction and module detection function. We constructed a weighted gene network using thresholding power β (β = 1 to 30) to calculate adjacency among the genes. Further, we chose the soft thresholding power (β = 16) to construct a network based on the criterion of approximate scale-free topology, using mergeCutHeight = 0.25 and minModuleSize = 30. We estimated the association between genes and various tissues using the Gene Significance (GS) score (whereby each tissue is considered a quality trait), the correlation of the module and the gene expression profile (MM) and the correlation of module with traits (module eigengene). This enabled us to identify the expression modules and genes that are closely related to each tissue. Lastly, the WGCNA results were exported to Cytoscape software to construct a gene coexpression network [37].

Pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes

To examine the metabolic pathways associated with the development of different tissues, we first identified the genes that were both included in modules related to specific traits, and were upregulated in each tissue relative to the other tissues at the same stage. Second, we performed a KEGG enrichment analysis, using KOBAS software, for the genes that were identified both in each tissue and each module [38, 39]. Third, we selected the 20 most significantly enriched pathways to visualize in the maps. When fewer than 20 pathways were significantly enriched, all were displayed.

Validation of differential gene expression

To validate the RNA-seq results, we compared a set of genes expression in this study with the report by Islam et al. [28], and analyzed the expression of 12 genes (7 that were directly regulated by transcription factor OMO55970.1, and five randomly selected from among the DEGs expressed in leaves and stem bast tissues during the vegetative growth period) by qRT-PCR, using three independent biological and three technological replicates. We used the jute elongation factor-alpha (ELF) gene as an endogenous control. The primer sequences of the DEGs and ELF are listed in Additional file 16: Table S13. The qRT-PCR was performed according to Yang et al. [20].

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or its supplementary information files. Sequencing raw data have been submitted to NCBI under accession number PRJNA612788.

Abbreviations

- WGCNA:

-

Weighted gene coexpression network analysis

- RPKM:

-

Reads per kilobase of exon model per million reads

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- GS:

-

Gene Significance

- MM:

-

Module membership

- qRT-PCR:

-

quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- RNA-seq:

-

RNA sequencing

- DEGs:

-

Differentially expressed genes

- ELF :

-

Elongation factor-alpha

- MF:

-

Mature flowers

- LVGP:

-

Leaf tissues of vegetative growth period

- LFP:

-

Leaf tissues of flowering period

- FT1:

-

Fruits < 0.8 cm in diameter

- FT2:

-

Fruits > 0.8 cm in diameter

- BVGP:

-

Bast of vegetative growth period

- BFP:

-

Bast of flowering period

References

Zhang G, Shan S, Wu Y, Huang S, Li D, Deng J, Qi J. The KCS gene is involved in the formation of chloroplast stromules and other physiological processes in jute (Corchorus capsularis L.). Ind Crop Prod. 2019;141:111781.

Bhattacharyya J, Chakraborty A, Roy S, Pradhan S, Mitra J, Chakraborty M, Manna A, Sikdar N, Chakraborty S, Sen SK. Genetic transformation of cultivated jute (Corchorus capsularis L.) by particle bombardment using apical meristem tissue and development of stable transgenic plant. Plant Cell Tissue Org. 2015;121(2):311–24.

Bhandari H, Bera A, Kar C, Biswas S. Stability assessment of jute seed production system in lower Gangetic plains of India. Ind Crop Prod. 2018;125:505–10.

Biswas C, Dey P, Karmakar P, Satpathy S. Discovery of large-scale SNP markers and construction of linkage map in a RIL population of jute (Corchorus capsularis). Mol Breeding. 2015;35(5):119.

Islam MM. Biochemistry, medicinal and food values of jute (Corchorus capsularis L. and C. olitorius L.) leaf: a review. Int J Enhanc Res Sci Technol Eng. 2013;2(11):135–44.

Siriamornpun S, Li D, Yang L, Kanchanamayoon W, Suttajit M. Thai jute seed oil: a potential polyunsaturated fatty acid source. J Sci Technol. 2006;28:11–5.

Maity S, Singha K, Gon DP, Paul P, Singha M. A review on jute nonwovens: manufacturing, properties and applications. Int J Textile Sci. 2012;1(5):36–43.

Liu X, Yu X, Zack DJ, Zhu H, Qian J. TiGER: a database for tissue-specific gene expression and regulation. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9(1):271.

Miao L, Zhang L, Raboanatahiry N, Lu G, Zhang X, Xiang J, Gan J, Fu C, Li M. Transcriptome analysis of stem and globally comparison with other tissues in Brassica napus. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1403.

Srivastava PL, Shukla A, Kalunke RM. Comprehensive metabolic and transcriptomic profiling of various tissues provide insights for saponin biosynthesis in the medicinally important Asparagus racemosus. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):9098.

Amini H, Naghavi MR, Shen T, Wang Y, Nasiri J, Khan IA, Fiehn O, Zerbe P, Maloof JN. Tissue-specific transcriptome analysis reveals candidate genes for terpenoid and phenylpropanoid metabolism in the medicinal plant ferula assafoetida. G3. 2019;9(3):807–16.

Gamboa-Tuz SD, Pereira-Santana A, Zamora-Briseño JA, Castano E, Espadas-Gil F, Ayala-Sumuano JT, Keb-Llanes MÁ, Sanchez-Teyer F, Rodríguez-Zapata LC. Transcriptomics and co-expression networks reveal tissue-specific responses and regulatory hubs under mild and severe drought in papaya (Carica papaya L.). Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):14539.

Garg R, Singh VK, Rajkumar MS, Kumar V, Jain M. Global transcriptome and coexpression network analyses reveal cultivar-specific molecular signatures associated with seed development and seed size/weight determination in chickpea. Plant J. 2017;91(6):1088–107.

Feng G, Huang L, Li J, Wang J, Xu L, Pan L, Zhao X, Wang X, Huang T, Zhang X. Comprehensive transcriptome analysis reveals distinct regulatory programs during vernalization and floral bud development of orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2017;17(1):216.

Tan M, Cheng D, Yang Y, Zhang G, Qin M, Chen J, Chen Y, Jiang M. Co-expression network analysis of the transcriptomes of rice roots exposed to various cadmium stresses reveals universal cadmium-responsive genes. BMC Plant Biol. 2017;17(1):194.

Satya P, Chakraborty A, Jana S, Majumdar S, Karan M, Sarkar D, Datta S, Mitra J, Kar CS, Karmakar PG. Identification of genic SSR s in jute (Corchorus capsularis, Malvaceae) and development of markers for phenylpropanoid biosynthesis genes and regulatory genes. Plant Breed. 2017;136(5):784–97.

Yang Z, Dai Z, Xie D, Chen J, Tang Q, Cheng C, Xu Y, Wang T, Su J. Development of an InDel polymorphism database for jute via comparative transcriptome analysis. Genome. 2018;61(5):323–7.

Tao A, Huang L, Wu G, Afshar RK, Qi J, Xu J, Fang P, Lin L, Zhang L, Lin P. High-density genetic map construction and QTLs identification for plant height in white jute (Corchorus capsularis L.) using specific locus amplified fragment (SLAF) sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1):355.

Zhang L, Ming R, Zhang J, Tao A, Fang P, Qi J. De novo transcriptome sequence and identification of major bast-related genes involved in cellulose biosynthesis in jute (Corchorus capsularis L.). BMC Genomics. 2015;16(1):1062.

Yang Z, Lu R, Dai Z, Yan A, Tang Q, Cheng C, Xu Y, Yang W, Su J. Salt-Stress response mechanisms using de novo transcriptome sequencing of salt-tolerant and sensitive Corchorus spp. genotypes. Genes. 2017;8(9):226.

Samanta P, Sadhukhan S, Basu A. Identification of differentially expressed transcripts associated with bast fibre development in Corchorus capsularis by suppression subtractive hybridization. Planta. 2015;241(2):371–85.

Pattison RJ, Csukasi F, Zheng Y, Fei Z, van der Knaap E, Catalá C. Comprehensive tissue-specific transcriptome analysis reveals distinct regulatory programs during early tomato fruit development. Plant Physiol. 2015;168(4):1684–701.

Singh VK, Garg R, Jain M. A global view of transcriptome dynamics during flower development in chickpea by deep sequencing. Plant Biotechnol J. 2013;11(6):691–701.

Sharma R, Agarwal P, Ray S, Deveshwar P, Sharma P, Sharma N, Nijhawan A, Jain M, Singh AK, Singh VP. Expression dynamics of metabolic and regulatory components across stages of panicle and seed development in indica rice. Funct Integr Genomic. 2012;12(2):229–48.

Waese J, Fan J, Pasha A, Yu H, Fucile G, Shi R, Cumming M, Kelley LA, Sternberg MJ, Krishnakumar V. ePlant: visualizing and exploring multiple levels of data for hypothesis generation in plant biology. Plant Cell. 2017;29(8):1806–21.

Kamenetsky R, Faigenboim A, Mayer ES, Michael TB, Gershberg C, Kimhi S, Esquira I, Shalom SR, Eshel D, Rabinowitch HD. Integrated transcriptome catalogue and organ-specific profiling of gene expression in fertile garlic (Allium sativum L.). BMC Genomics. 2015;16(1):12.

Alonso-Serra J, Safronov O, Lim KJ, Fraser-Miller SJ, Blokhina OB, Campilho A, Chong SL, Fagerstedt K, Haavikko R, Helariutta Y. Tissue-specific study across the stem reveals the chemistry and transcriptome dynamics of birch bark. New Phytol. 2019;222(4):1816–31.

Islam MS, Saito JA, Emdad EM, Ahmed B, Islam MM, Halim A, Hossen QMM, Hossain MZ, Ahmed R, Hossain MS. Comparative genomics of two jute species and insight into fibre biogenesis. Nat Plants. 2017;3(2):16223.

Ehlting J, Mattheus N, Aeschliman DS, Li E, Hamberger B, Cullis IF, Zhuang J, Kaneda M, Mansfield SD, Samuels L. Global transcript profiling of primary stems from Arabidopsis thaliana identifies candidate genes for missing links in lignin biosynthesis and transcriptional regulators of fiber differentiation. Plant J. 2005;42(5):618–40.

Kohorn BD, Kobayashi M, Johansen S, Friedman HP, Fischer A, Byers N. Wall-associated kinase 1 (WAK1) is crosslinked in endomembranes, and transport to the cell surface requires correct cell-wall synthesis. J Cell Sci. 2006;119(11):2282–90.

Yang Z, Dai Z, Lu R, Wu B, Tang Q, Xu Y, Cheng C, Su J. Transcriptome analysis of two species of jute in response to polyethylene glycol (PEG)-induced drought stress. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):16565.

Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):357.

Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(9):1105–11.

Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods. 2008;5(7):621.

Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression of RNA-Seq data at the gene level–the DESeq package. Heidelberg: European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL); 2012.

Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9(1):559.

Kohl M, Wiese S, Warscheid B. Cytoscape: software for visualization and analysis of biological networks. Methods Mol Biol. 2011:291–303.

Mao X, Cai T, Olyarchuk JG, Wei L. Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG Orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(19):3787–93.

Kanehisa M, Goto S, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Hirakawa M. KEGG for representation and analysis of molecular networks involving diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D355–60.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 31601351), the Hunan Natural Science Foundation (grant number 2017JJ3350), the Science and Technology Innovation Project of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (grant number CAAS-ASTIP-2017-IBFC01 and CAAS-XTCX2016016–2), National hemp industry technical system (grant number CARS-16-E01) and the Germplasm Resources Protection Project (grant number 2016NWB044). The funding bodies did not participate in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in the writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JS and ZY designed the study. ZY performed most of the experiments. ZD, JS, ZY and JC contributed to the acquisition of plant materials. ZY, XC, DX, QT and CD analyzed the data. ZY, CC, YX, and CL conducted the molecular experiments. ZY and JS wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Transcriptional genes that were identified in stem bast tissue during the vegetative growth period (BVGP).

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Transcriptional genes that were identified in bast tissue during the flowering period (BFP).

Additional file 3: Table S3.

Transcriptional genes that were identified in leaf tissues during the vegetative growth period (LVGP).

Additional file 4: Table S4.

Transcriptional genes that were identified in leaf tissues during the flowering period (LFP).

Additional file 5: Table S5.

Transcriptional genes that were identified in fruit < 0.8 cm in diameter (FF1).

Additional file 6: Table S6.

Transcriptional genes that were identified in fruit > 0.8 cm in diameter (FF2).

Additional file 7: Table S7.

Transcriptional genes that were identified in flower tissues.

Additional file 8: Table S8.

Transcriptional genes that were identified in all tissues during differential stages.

Additional file 9: Table S9.

Upregulated genes that were identified by comparing bast tissue during the vegetative growth period (BVGP) with leaf tissue during the vegetative growth period (LVGP).

Additional file 10: Table S10.

Downregulated genes that were identified by comparing bast tissue during the vegetative growth period (BVGP) with leaf tissue during the vegetative growth period (LVGP).

Additional file 11: Figure S1.

Enriched terms for the genes that overlapped between the gene modules related to traits and the candidate upregulated genes, obtained using KEGG enrichment analysis.

Additional file 12: Figure S2.

Enriched terms for the genes that overlapped between the gene modules related to traits and the candidate upregulated genes, obtained using KEGG enrichment analysis.

Additional file 13: Figure S3.

RNA-seq and qRT-PCR analysis results for the genes directly regulated by transcription factor (OMO55970.1), and for the five genes that were randomly selected from among the genes that were differentially expressed between the bast tissueand the leaf tissue during the vegetative growth period.

Additional file 14: Table S11.

Common upregulated genes identified in bast tissue during the vegetative growth period in our study and in fibre cells which were included bast tissue identified by comparing fibre cells with seedling reported by Islam et al. [28].

Additional file 15: Table S12.

Common downregulated genes identified in bast tissue during the vegetative growth period in our study and in fibre cells which were included bast tissue identified by comparing fibre cells with seedling reported by Islam et al. [28].

Additional file 16: Table S13.

The primer sequences used for ELF, for the seven genes that were directly regulated by transcription factor (OMO55970.1), and for the five genes that were randomly selected from among the differentially expressed genes.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Z., Dai, Z., Chen, X. et al. Gene coexpression network analysis and tissue-specific profiling of gene expression in jute (Corchorus capsularis L.). BMC Genomics 21, 406 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-020-06805-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-020-06805-6