Abstract

There are many achievements in the field of analytical mechanics, such as Lagrange Equation, Hamilton’s Principle, Kane’s Equation. Compared to Newton–Euler mechanics, analytical mechanics have a wider range of applications and the formulation procedures are more mathematical. However, all existing methods of analytical mechanics were proposed based on some auxiliary variables. In this review, a novel analytical mechanics approach without the aid of Lagrange’s multiplier, projection, or any quasi or auxiliary variables is introduced for the central problem of mechanical systems. Since this approach was firstly proposed by Udwadia and Kalaba, it was called Udwadia–Kalaba Equation. It is a representation for the explicit expression of the equations of motion for constrained mechanical systems. It can be derived via the Gauss’s principle, d’Alembert’s principle or extended d’Alembert’s principle. It is applicable to both holonomic and nonholonomic equality constraints, as long as they are linear with respect to the accelerations or reducible to be that form. As a result, the Udwadia–Kalaba Equation can be applied to a very broad class of mechanical systems. This review starts with introducing the background by a brief review of the history of mechanics. After that, the formulation procedure of Udwadia–Kalaba Equation is given. Furthermore, the comparisons of Udwadia–Kalaba Equation with Newton–Euler Equation, Lagrange Equation and Kane’s Equation are made, respectively. At last, three different types of examples are given for demonstrations.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Classical mechanics is divided into Newton–Euler mechanics [1] and analytical mechanics (i.e., Lagrangian mechanics) [2, 3]. In 1687, Sir Isaac Newton proposed three fundamental laws of motion for a hypothetical object called particle, which is the physical foundation of classical mechanics. In the 18th century, Euler extended Newton’s laws to rigid bodies. In Newton–Euler mechanics, forces are divided into internal forces (originating wholly from within the system) and external forces (originating from outside the system).

Lagrange divided the forces into constraint forces (depending exclusively on the constraints) and given (or impressed) forces (depending on physical coefficients). Generalizing the d’Alembert’s principle [4, 5] for statics, Lagrange formulated the analytical mechanics via the notions of “virtual displacement” and “virtual work” in 1788. Lagrange introduced “generalized coordinates” (also called Lagrange coordinates) to reduce the number of equations of both motion and constraints. In Lagrange’s equation of motion, the Lagrange multiplier part is added to describe the motion of the constrained system [6, 7]. However, Lagrange multipliers are not explicitly represented as functions of the generalized coordinates and generalized velocities.

Subsequent to Lagrange, Hamilton developed analytical mechanics with his well-known Hamilton’s Principle [8] in 1834, which provides an alternative derivation of Lagrange’s equations. Hamilton’s equation of motion [9] is founded on a relation between momentum and kinetic energy. In the 1840’s, Jacobi proposed an integration theory of dynamics to describe the motion of the system, which we call Jacobi’s integral [10]. In the 1870’s, Routh’s method for ignorable coordinates was presented as an alternative elimination procedure to obtain the equation of motion [10]. Gauss Principle [11] for inequality constraints and Appell’s equations for unconstrained systems were founded in 1879. Soon afterwards Appell explored the dynamics of nonholonomic systems under linear (or Pfaffian) velocity constraints [12]. Between 1910’s and 1930’s, Appell and Hamel explored the dynamics of nonholonomic systems under nonlinear velocity constraints [10, 13]. Hamel’s method of formulating the constrained equation of motion embedded the constraint into the kinetic energy of the unconstrained motion directly [14]. Quasi variables in Hamel’s method are not physically measurable [15]. This method seemed to be simple, intuitive, but not always available [16, 17]. In the 1960’s, Kane developed an equation based on the use of quasi-velocities [18, 19].

Despite all these great developments in classical mechanics and principles of mechanics [5, 20,21,22,23], there had been one missing piece. For systems subject to nonholonomic constraints, the analytical expressions of the equations of motion were still either not available or practical. All existing methods only provided the equation of motion in terms of some auxiliary variables (such as the Lagrange multiplier or other quasi variables [24,25,26]), in addition to the generalized coordinates. This had hindered certain fundamental explorations, such as stability, chaos, bifurcation, which are mostly performed based on the analytic expressions. Hence, the research of this ultimate analytical form of the equations of motion of constrained systems continued.

A major breakthrough was made in the 1990’s. Udwadia and Kalaba proposed a novel approach to this central problem in classical mechanics [27,28,29,30,31]. It can be proved via the Gauss principle, d’Alembert’s principle, or extended d’Alembert’s principle [32,33,34,35]. This creative approach provides the analytical expression of the equation of motion of a constrained mechanical system, where the constraints can be holonomic and/or nonholonomic. The constraint force is represented in closed form: only based on the generalized coordinates/velocities. No other auxiliary variables are needed. This is by far the simplest form and completed the quest which lasted for more than 200 years (since 1788).

In this review paper, we present the Udwadia–Kalaba Equation in a straightforward and approachable manner. We utilize examples to further illustrate the Udwadia–Kalaba Equation. These will demonstrate the applicability of the equation to a very broad range of engineering problems.

2 Equation of Motion of Unconstrained System

Consider an unconstrained mechanical system described by an n dimensional coordinate \(q \in \varvec{R}^{n} ,\) velocity \(\dot{q} \in {\varvec{R}}^{n} ,\) and acceleration \(\ddot{q} \in {\varvec{R}}^{n}\). The dynamic model of the unconstrained mechanical system can be represented by

where \(M(q,\;t) \in \varvec{R}^{n \times n}\) is the inertia matrix, \(F(q,\;\dot{q},\;t) \in {\varvec{R}}^{n}\) includes the given force (also called the impressed force), Coriolis/centrifugal force, and gravitational force [7]. The functions \(M( \cdot ):{\varvec{R}}^{n} \times {\varvec{R}} \to {\varvec{R}}^{n \times n}\) and \(F( \cdot ):{\varvec{R}}^{n} \times {\varvec{R}}^{n} \times {\varvec{R}} \to {\varvec{R}}^{n}\) are continuous.

Remark 1.

Equation (1) can be obtained through the use of Newton–Euler mechanics or analytical mechanics. We omit the details since this is often discussed in standard mechanics books (for example, Refs. [1, 7]).

We now demonstrate this via examples.

Example 1.

Consider a particle m that makes a horizontal projectile motion under the influence of gravity.

With respect to a Cartesian coordinate system which is rigidly attached to an inertial reference frame, let x denote the horizontal coordinate and y denote the vertical coordinate. The equation of motion is given by

where g is the gravitational constant. This is in the form of Eq. (1) with \(q = [x\;y]^{\text{T}} ,\) the inertia matrix \(M = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} m & 0 \\ 0 & m \\ \end{array} } \right]\), and the given force \(F = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} 0 \\ { - mg} \\ \end{array} } \right]\).

With respect to polar coordinate, we let r denote the radial coordinate or radius, θ denote the angular coordinate. The relation between Cartesian coordinate and polar coordinate is followed by

Differentiating Eq. (3) with respect to t yields

After continue differentiating Eq. (4), we obtain

Combining Eqs. (2) and (5) leads to

After multiplying by \(\cos\theta\) on the first equation of Eq. (6) and by \(\sin\theta\) on the second equation of Eq. (6) and adding them, we have

After multiplying by \(\sin\theta\) on the first equation in Eq. (6) and by \(\cos\theta\) on the second equation in Eq. (6) and subtracting them, we have

Therefore, the equation of motion in polar coordinate is given by

where \(q = [r\;\theta ]^{\text{T}} ,\) the inertia matrix \(\varvec{M} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} m & 0 \\ 0 & m \\ \end{array} } \right]\), the given force \(\varvec{F} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {mr\mathop {\dot{\theta }}\nolimits^{2} - mg \sin\theta } \\ {\tfrac{{ - 2m\dot{r}\dot{\theta } - mg \cos\theta }}{r}} \\ \end{array} } \right]\).

3 Constraints

In practice, the motions of mechanical systems are always constrained in some way [36,37,38,39].

Definition 1.

A constraint of the form \(f(q,t) = 0\), or reducible to that form, is called a holonomic constraint. Every constraint not of this form, or not reducible to it, is called nonholonomic [1].

According to whether the holonomic constraints depend explicitly on time or not, they can be classified into scleronomic or rheonomic.

Definition 2.

A holonomic constraint of the form \(f(q) = 0\), or reducible to it, is called scleronomic. Every holonomic constraint not of this form (hence in the form of \(f(q,t) = 0\)), or not reducible to it, is called rheonomic [1].

In analytical mechanics, it is traditionally crucial to identify the holonomicity of constraints. The following lemma is introduced firstly, which will be used latter.

Lemma 1.

Consider the following Pfaffian form of constraint (in which \(q = [x\;y\;z]^{\text{T}}\)) [1]

The constraint is holonomic if and only if

where α, β, and γ are functions of x, y, and z.

This is a necessary and sufficient condition. If the constraint is not holonomic, then it is nonholonomic. Different types of constraints can be seen in the following three examples. Here, we assume x, y, z are the coordinates.

Example 2: (Scleronomic constraint)

Consider a constraint

It shows that Eq. (12) is scleronomic. Take the integral of Eq. (12) with respect to the time t, then we reformulate the equation as

where L is a constant. According to Definitions 1 and 2, we know that constraint Eq. (12) is not only holonomic but also scleronomic.

Example 3: (Rheonomic constraint)

Consider a constraint

It shows that Eq. (14) is rheonomic. Take the integral of Eq. (14) with respect to the time t, then we reformulate the equation as

where L is a constant. According to Definitions 1 and 2, we know that constraint Eq. (14) is not only holonomic but also rheonomic.

Example 4: (Nonholonomic constraint)

Consider a constraint

with \(\alpha = 1\), \(\beta = 2z\), \(\gamma = 1\), we have

According to Lemma 1, we conclude that the constraint Eq. (16) is nonholonomic.

The standard second order form of constraints in Udwadia and Kalaba’s setting [27] is given by

where \(A(q,\dot{q},t) \in \varvec{R}^{m \times n}\), \(b(q,\dot{q},t) \in {\varvec{R}}^{n}\).

Assumption 1.

(i) Rank \(A(q,\dot{q},t) \ge 1\). (ii) The second order constraint Eq. (18) is consistent. That is, for given \(A(q,\dot{q},t)\) and \(b(q,\dot{q},t)\), there exists at least one solution \(\ddot{q}\) to Eq. (18).

The constraint Eq. (18) encompasses a very broad variety of constraints [40]. It includes both holonomic and nonholonomic constraints. For example, the holonomic constraints of the form \(f(q,t) = 0\) can be taken the second-order derivative with respect to time t while nonholonomic constraints of the form \(f(q,\dot{q},t) = 0\) can be taken once with respect to time t to obtain the form of Eq. (18).

The standard form of the constraint in Example 2 can be reformulated as

where \(\varvec{A} = [1\;\;2y\;\;1],\) \(\varvec{q} = [x\;y\;z]^{\text{T}} ,\)\(b = - 2\mathop {\dot{y}}\nolimits^{2} .\) The standard form of the constraint in Example 3 is the same as Eq. (19). The standard form of the constraint in Example 4 can be reformulated as

where \(\varvec{A} = [1\;\;2z\;\;1],\) \(\varvec{q} = [x\;y\;z]^{\text{T}} ,\) \(b = - 2\dot{y}\dot{z}.\) We now generalize our results in the following two cases.

Case I.

Suppose the system is restricted by \(m\) constraints in the first order form (Pfaffian representation) of

or equivalently in the form of

Taking the derivative of Eq. (22) yields

where

and

Let

we can reformulate Eq. (23) in the form of

Expressing Eq. (26) in matrix form with \(\varvec{A} = [A_{ij} ]_{m \times n}\) and \(\varvec{b} = [b_{1} \quad b_{2} \quad \cdots \quad b_{m} ]^{\text{T}}\), leads to the standard second order form Eq. (18).

Case II.

Suppose the system is restricted by \(m\) constraints in the form of

Taking the derivative of Eq. (27) leads to

or equivalently in the Pfaffian form

Notice that Eq. (28) is in the form of Eq. (22) with

Then we take the same procedure as in Case I to obtain the standard form Eq. (18).

Remark 2.

In Udwadia–Kalaba’s setting, it considers only those constraints which can be expressed as linear equality relations with respect to the accelerations of the particles of the system. That is, the constraint of the form Eq. (18), or that can be differentiated to it, is applied to Udwadia–Kalaba Equation.

4 Moore–Penrose (MP) Inverse

We start with introducing the mathematical preliminaries.

Definition 3.

Consider a matrix \(\varvec{W} \in \varvec{R}^{p \times q}\) with rank \(r \ge 1\). Its singular values are given by \(\delta_{1} \ge \delta_{2} \ge \cdots \ge \delta_{r} > 0\). Suppose that its singular-value decomposition is given by \({\varvec{U\Delta V}}^{\text{T}} ,\) where both \({\varvec{U}} = \left\{ {u_{1} , \cdots ,u_{r} } \right\} \in \varvec{R}^{p \times r}\) and \({\varvec{V}} = \left\{ {v_{1} , \cdots ,v_{r} } \right\} \in {\varvec{R}}^{q \times r}\) are unitary matrices [10]:

with \({\varvec{\Delta}} = [{\text{diag}}(\delta_{i} )]_{r \times r} .\). Here, \(\left\{ {u_{1} , \cdots ,u_{r} } \right\}\) and \(\left\{ {v_{1} ,} \right.\left. { \cdots ,v_{r} } \right\}\) are orthonormal sets of vectors in \({\varvec{R}}^{p}\) and \({\varvec{R}}^{q}\), respectively. The Moore–Penrose inverse \({\varvec{W}}^{ + } \in {\varvec{R}}^{q \times p}\) of W is given by

Lemma 2.

The \(q \times p\) matrix \(\varvec{W}_{0}\) is the MP inverse \({\varvec{W}}^{ + }\) of W if and only if the following conditions hold [41]:

Moreover, \(\varvec{W}^{ + }\) is unique. Conditions (34) and (35) imply that the matrices \({\varvec{WW}}_{0}\) and \(\varvec{W}_{0} {\varvec{W}}\) are symmetric.

Some propositions of MP inverse are provided as follows to help with finding the MP inverse [27, 42, 43].

Proposition 1.

\(({\varvec{\lambda A}})^{ + } = {\varvec{A}}^{ + } /{\varvec{\uplambda}}\), where \({\varvec{\lambda}}\) is a nonzero scalar.

Proposition 2.

If a is a nonzero 1 by n row vector, then \({\varvec{a}}^{ + } = {\varvec{a}}^{\text{T}} /({\varvec{aa}}^{\text{T}} )\).

Proposition 3.

If a is a nonzero n by 1 column vector, then \({\varvec{a}}^{ + } = {\varvec{a}}^{\text{T}} /({\varvec{a}}^{\text{T}} {\varvec{a}})\).

Proposition 4.

If a is a nonzero 1 by n vector, then \(({\varvec{a}}^{\text{T}} {\varvec{a}})^{ + } = ({\varvec{a}}^{\text{T}} {\varvec{a}} ) /({\varvec{aa}}^{\text{T}} )^{2}\).

Proposition 5.

If \({\varvec{A}} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} B & 0 \\ 0 & C \\ \end{array} } \right]\), then \({\varvec{A}}^{ + } = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {B^{ + } } & 0 \\ 0 & {C^{ + } } \\ \end{array} } \right]\), where B and C are modules of matrix A.

5 Udawadia–Kalaba Equation

We consider the mechanical system (1) is subject to the constraint (18).

Assumption 2.

The inertia matrix \({\varvec{M}}(q,t)\) is positive definite: For each \((q,t) \in {\varvec{R}}^{n} \times {\varvec{R}}\), \({\varvec{M}}(q,t) > 0\).

Subject to Assumptions 1 and 2, the Udawadia–Kalaba Equation of the corresponding constrained mechanical system is given by [27]

Here \({\varvec{F}}^{C} (q,\dot{q},t) \in {\varvec{R}}^{n}\) is the constrained force.

Subject to Assumptions 1 and 2, the constraint force \(F^{C}\) always exists. The constrained mechanical system Eq. (36) meets the constraint Eq. (18). The constraint force is obtained in closed form (i.e., analytical form).

This Udawadia–Kalaba Equation can be derived via the Gauss principle [44], d’Alembert’s principle [45], or extended d’Alembert’s principle [46, 47].

So far, the Udawadia–Kalaba Equation is the only equation that is without the use of Lagrange multiplier, projection, or any quasi or auxiliary variables. It does not increase the dimension of the original unconstrained system. All it takes is to find the MP inverse of the designated matrix. Therefore, it is simple, straightforward, and practical. The equation can be applied to a very broad range of problems. Its applications can be found in, e.g., Refs. [48,49,50,51,52,53].

6 Comparison with Other Methods

The Udwadia–Kalaba Equation provides a novel approach of describing the motion of discrete mechanical systems, which is different from other methods such as Newton–Euler Equation, Lagrange Equation [54], Maggi approach [55] or Kane’s Equation [19]. Next, we will compare Udwadia–Kalaba Equation with some of these approaches.

6.1 Comparison with Newton–Euler Equation

Consider a rigid body \({\mathcal{B}}\). With respect to a coordinate system, rigidly attached to \({\mathcal{B}}\), whose origin is a point P and not necessarily coincident with the center of mass of \({\mathcal{B}}\), the Newton–Euler Equation is in the form of

Here

and

denote skew-symmetric cross product matrices, c is the location of the center of mass, m is the mass, \(a_{P}\) is the acceleration, \(I_{cm}\) is the moment of inertia, \(\omega\) is the angular velocity, \(\alpha\) is the angular acceleration, F is the total force (including internal and external), \(\tau_{P}\) is the total moment.

There are two major differences with the Udwadia–Kalaba Equation.

First, the Newton–Euler Equation is typically represented in terms of physical coordinates (such as Cartesian, cylindrical, or spherical), while Udwadia–Kalaba Equation can be formulated, in addition to physical coordinates, generalized coordinates.

Second, forces in Newton–Euler Equation are divided into internal forces (originating wholly from within the system) and external forces (originating from outside the system). Forces in Udwadia–Kalaba Equation are divided into given (or impressed) forces (depending on physical coefficients) and constraint forces (depending exclusively on the constraints). It is emphasized that internal/external distinction of forces is different from given/constraint distinction. That is to say, in general, the constraint force is not the same as internal force and the given force is not the same as external force. The number of internal forces, despite of the characterization of the Newton’s third law, is often greater than the constraints, hence cannot be uniquely determined. That makes the Newton–Euler Equation hard to formulate when the system is subject to constraints. The constraint force, on the other hand, can be solved analytically in Udwadia–Kalaba Equation.

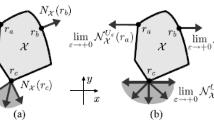

6.2 Comparison with Lagrange Equation

Although the Udwadia–Kalaba Equation is similar to Lagrange Equation in the classification of forces and the use of constraints, their representations of constraint forces are totally different. There is no Lagrange’s multiplier, projection, or any quasi or auxiliary variables in the Udwadia–Kalaba Equation. Comparing to Lagrange Equation, Udwadia–Kalaba Equation is simpler. It provides the closed-form constraint force for a large classes of constrained mechanical systems, which is subject to the d’Alembert’s principle (i.e., the totality of the virtual work done by the constraint force is zero [1]) and drives the mechanical systems to follow the constraints.

Consider the same mechanical system Eq. (1) in Section 2. Notice that, in Lagrange Equation, the coordinate \({\varvec{q}} \in {\varvec{R}}^{n}\) is a generalized coordinate, which can be denoted as \({\varvec{q}} = [q_{1} \quad q_{2} \quad \cdots \quad q_{n} ]^{\text{T}}\). Suppose that the system is under \(m( < n)\) constraints Eq. (22), or equivalently in the matrix form of

where \({\varvec{A}} = [A_{ij} ]_{m \times n} ,\)\(c = [c_{1} \; c_{2} \; \cdots \; c_{m} ]^{\text{T}} .\) Let \({\varvec{Q}}(q,\dot{q},t) = [Q_{1} \; Q_{2} \; \cdots \; Q_{n} ]^{\text{T}}\) denote the generalized force, \({\varvec{Q}}^{c} = [Q_{1}^{c} \; Q_{2}^{c} \; \cdots \; Q_{n}^{c} ]^{\text{T}}\) denote the constraint force, \(\delta q = [\delta q_{1} \; \delta q_{2} \; \cdots \; \delta q_{n} ]^{\text{T}}\) denote the virtual displacement. The virtual displacement \(\delta q\) is governed by

According to Ref. [13], for each \(j = 1,2, \ldots ,n\), we have

Adopting the Lagrange’s form of d’Alembert’s principle (also called the fundamental equation) yields

or in the matrix form

After the use of the Principle of Relaxation of the constraints [14], for each \(j = 1,2, \cdots ,n,\) the resulting Lagrange Equation is given in the form of

where \(\lambda_{i}\) denote the Lagrange’s multiplier. The constraint force component \(Q_{j}^{c} = \sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{m} \,A_{ij} (q,t)\lambda_{i}\). Rewriting Eq. (45) in the matrix form yields

where \({\varvec{\lambda}} = [\lambda_{1} \; \lambda_{2} \; \cdots \; \lambda_{m} ]^{\text{T}} ,\) \({\varvec{A}}^{\text{T}} (q,t){\varvec{\lambda}}\) denotes the constraint force \({\varvec{Q}}^{c}\).

According to Ref. [1], the kinetic energy of the system in the terms of generalized coordinates is given by

where \({\varvec{M}}(q,t) = {\varvec{M}}^{\text{T}} (q,t),\)\({\varvec{N}}(q,t)\) is an \(1\) by n vector, \({\varvec{P}}(q,t)\) is a scalar. Substituting Eq. (47) into Eq. (46), then we have

Here the Lagrange multiplier \(\lambda\) is in general solved numerically (with the exception of highly simplified examples) based on given initial condition \(q(t_{0} )\) and \(\dot{q}(t_{0} )\) together with the constraint Eq. (40). The term \({\varvec{A}}^{\text{T}} (q,t){\varvec{\lambda}}\) corresponds to the constraint force \({\varvec{F}}^{c} (q,\dot{q},t)\) in the Udwadia–Kalaba Equation. Since Eq. (40) can be obtained the form of Eq. (18) after taking derivative with respect to time t, the Udwadia–Kalaba Equation of the mechanical system Eq. (1) constrained by Eq. (40) is given by Eq. (36).

Comparing Udwadia–Kalaba Equation with Lagrange Equation, there are three major distinctions. First, the Lagrange multiplier λ should be solved numerically in general for each initial condition and constraint. The constraint force \({\varvec{F}}^{c} (q,\dot{q},t)\) in Udwadia–Kalaba Equation can always be represented in analytic form (i.e., closed form). Second, for a given constraint force \({\varvec{F}}^{c} (q,\dot{q},t)\), the Lagrange multiplier is in fact non-unique (unless with more provision on the matrix \({\varvec{A}}^{\text{T}} (q,t)\)). It is just that \({\varvec{A}}^{\text{T}} (q,t){\varvec{\lambda}}\) is unique. Third, the Udwadia–Kalaba Equation is represented by \(q\) and \(\dot{q}\), no new variables are introduced and used. The Lagrange Equation, in addition to \(q\) and \(\dot{q}\), requires the extra Lagrange multiplier \(\lambda \in {\varvec{R}}^{m}\), hence raising the dimension of the system from n to n + m.

6.3 Comparison with Kane’s Equation

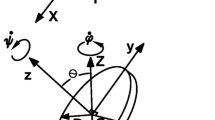

The Kane’s equation was proposed by Thomas R. Kane [18]. It has been widely applied to many engineering systems for modeling, analysis, and control. If S is a simple nonholonomic system possessing c degrees of freedom in reference frames N, then the Kane’s equation

govern all motions of S in any reference frame. Here the generalized forces \(\mathop {\tilde{F}}\nolimits_{r}\) and \(\mathop {\tilde{F}}\nolimits_{r}^{{ \star }}\) are obtained by using generalized speeds, inertia force, characteristics of the constraints, other kinematic quantities, etc. [18]. The generalized speeds (this is not to be confused with generalized velocities) are not necessarily physical quantities. Comparing Udwadia–Kalaba Equation with Kane’s Equation, one notable difference is that the former is always based on \(q\) and \(\dot{q}\). No pseudo variables are needed. Furthermore, the Udwadia–Kalaba Equation does not distinguish holonomic constraints from nonholonomic constraints.

7 Formulation Procedure

We show the procedure of formulating the Udwadia–Kalaba Equation by the following flow chart. As shown in Figure 1, the procedure can be summarized as follows.

-

(1)

Abstract and simplify the practical problem to mechanical system.

-

(2)

Determine the proper coordinate and system parameters.

-

(3)

Establish the unconstrained equation of motion based on the knowledge of Newton–Euler or Lagrange mechanics.

-

(4)

Establish the constraint equation.

-

(5)

Transform the constraint equation into standard form (second order form).

-

(6)

Obtain the closed-form constraint force.

-

(7)

Establish the constrained equation of motion.

8 Illustrative Examples

In previous sections, the procedure of establishing the equation of constrained motion through Udwadia–Kalaba Equation has been shown in details. In Sections 8.1 and 8.2, we will give examples to further illustrate this approach. The advantages of Udwadia–Kalaba Equation are not only in the modeling of constrained system, but also in the control design for constrained mechanical system [56,57,58,59,60,61]. For this point, we give an example in Section 8.3.

8.1 Motion of Constrained Particle

Consider a particle of unit mass moving along a logarithmic spiral orbit. The unconstrained motion is described by Eq. (9). Since the particle is of unit mass, the equation of unconstrained motion can be simplified to be

Let

The constraint is described by

where r is the radius, θ is the angle, e is the Euler’s number (\(e = \text{lim}_{n \to \infty } (1 + 1/n)^{n}\), \(e \approx 2.71828\)). The first order derivative of Eq. (53) is given by

Taking the second order derivative of Eq. (53), we have the second order constraint

where \({\varvec{A}} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} 1 & { - 0.1e^{0.1\theta } } \\ 0 & 1 \\ \end{array} } \right]\), \({\varvec{b}} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {0.01e^{0.1\theta } \mathop {\dot{\theta }}\nolimits^{2} } \\ 0 \\ \end{array} } \right]\). Substituting \(m = 1\) to Eq. (36), the constraint force yields

Hence, the Udwadia–Kalaba Equation is given by

For simulations, we choose the initial condition \(r(0) = e^{3}\), \(\theta (0) = 30\), \(\dot{r}(0) = - 0.1e^{3}\), \(\dot{\theta }(0) = - 1\). Then we simulate the equation of motion Eq. (57) via MATLAB. Define the errors as

Figure 2 depicts the relation between r and θ. The radius r decreases with the decreasing of θ. Figure 3 shows the time histories of r and θ, respectively. We notice that r settles to a very small magnitude after \(t \ge 20\), while θ can be described as a linear function with respect to t. By using the relationship Eq. (3) between Cartesian and polar coordinates, we have Figure 4 to show the trajectories of the constrained particle. Point G in Figure 4 is the starting point. Starting at G, the particle moves inward along the spiral. Figure 5 depicts the errors \(\varepsilon_{1}\) and \(\varepsilon_{2}\).

Relation between r and θ in constrained system Eq. (57)

Histories of the particle in constrained system Eq. (57)

Trajectory of the particle in constrained system Eq. (57)

Error of the constrained system Eq. (57)

8.2 Motion of Swarm Robotic System

Consider a swarm system consisting of five mobile robots moving in a horizontal road as shown in Figure 6. The equation of motion of the robot i is given by

where \(M_{i} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {m_{i} } & 0 \\ 0 & {m_{i} } \\ \end{array} } \right]\), \(q^{i} = [x_{i} \quad y_{i} ]^{\text{T}}\). In such a system, each robot has an interaction with another. Through the agent–agent interaction, the robots swarm system mimics a collective behavior. Each agent is constrained by

Subject to the swarm properties [51], we choose the function \(G_{ij}\) in the form of

Differentiating Eq. (61) with respect to time t yields

Adopting Udwadia–Kalaba’s Equation of Motion, the constraint force of agent i is given by

here \(A_{i} = I_{i}\), \(b_{i} = \varphi_{i}\). Let

here \(\beta_{i}\) can represent the error of the agent i relative to the ideal performance Eq. (61). If \(\beta_{i} = 0\), the agent i behaves exactly identical to the ideal performance Eq. (61). If \(\beta_{i} \ne 0\), then the behavior of agent i deviates from the ideal performance. Let \({\varvec{\upbeta}} = [\beta_{1} \quad \beta_{2} \quad \beta_{3} \quad \beta_{4} \quad \beta_{5} ]^{\text{T}}\) denote the swarm system performance error.

For simulations, we choose \(m_{i} = 2\;{\text{kg,}}\) \(F_{i} = [0\quad 0]^{\text{T}}\). The initial conditions are listed in Table 1. Figure 7 shows the trajectories of five robots under the constraint (61). The marked dots denote the robots’ initial positions. From Figure 7, we can see that, the robots never collide, which aggregate towards the swarm center when they are far away from the swarm center and they move apart when they are too close with each other. Figure 8 depicts the error magnitude \(\left\| {\beta (t)} \right\|\) under the constraint force obtained by Udwadia–Kalaba Equation. It can be seen that \(\left\| {\beta (t)} \right\|\) rapidly descends from a large initial magnitude to a very small magnitude (less than 0.01), which verifies the accuracy of the closed-form solution Eq. (64).

Trajectories of five robots under the constraint force Eq. (64)

The \(\left\| \beta \right\|\) history under the constraint force Eq. (64)

8.3 Motion of Constrained Flexible Joint Manipulator

In Figure 9, we consider a two-link flexible joint manipulator to verify the effectiveness of Udwadia–Kalaba Equation. The system is described by the following equation [62]

where \(q_{1} = [q^{(2)} \;q^{(4)} ]^{\text{T}}\) is link position vector, \(q_{2} = [q^{(1)} \;q^{(3)} ]^{\text{T}}\) is joint position vector, \(q = [q_{1}^{\text{T}} \;q_{2}^{\text{T}} ]^{\text{T}}\) represents the generalized coordinate for the system. The joint and link flexibility can be treated as linear torsional spring whose elasticity coefficient is K. \(\varvec{D}(q_{1} )\) is the link inertia matrix and J is a diagonal matrix representing the inertia of actuators, \(C\left( {q_{1} , \, \dot{q}_{1} } \right)\dot{q}_{1}\) represents the Coriolis and centrifugal force, \(G\left( {q_{1} } \right)\) is the gravitation force, and u is the input force from motors. These matrices are given by

where \(m_{1} (m_{2} )\) is the mass of link, \(l_{1}\) is the length of the first link, \(l_{c1} (l_{c2} )\) is the center position of the link (suppose that mass is uniform on the link), g is gravitational constant and

For simplicity, we require that the velocities of the link angles meet the following constraint:

which means

Let \(\beta (t) = A(q_{1} ,t)\mathop {\dot{q}}\nolimits_{1} - c(q_{1} ,t)\) stand for the tracking error of the constraint, according to Udwadia–Kalaba Equation, the constraint force should be

This in turn means that if a control in form of Eq. (71) is applied to such system, then the system should meet the constraint. Without loss of generality, for any initial condition which is not satisfied the constraint, the following control can drive the system to meet the constraint

where P is a positive definite matrix.

The simulation is performed with \(m_{1} = m_{2} = 1\), \(l_{1} = 1\), \(l_{c1} = l_{c2} = 0.5\), \(K_{1} = K_{2} = 1\), \(I_{1} = I_{2} = 1\), \(J_{11} = J_{22} = 1\), \(g = 9.81\). The initial condition is \(\mathop {\dot{q}}\nolimits^{(2)} (0) = 1\;{\text{m/s}}\) and \(\dot{q}^{(4)} (0) = - 0.1\;{\text{m/s}} .\) Then, in the very beginning, the constraint is not satisfied since \(\beta = \mathop {\dot{q}}\nolimits^{(2)} (0) + \mathop {\dot{q}}\nolimits^{(4)} (0) = 0.9\; \text{m/s} \ne 0\). By using the proposed control scheme, system performance meets the constraints after a certain time (no more than 2 s). Figure 10 shows the constrained system performance (i.e., \(\left\| \beta \right\| = \left\| {\mathop {\dot{q}}\nolimits^{(2)} + \mathop {\dot{q}}\nolimits^{(4)} } \right\|\)). This corresponds to the Udwadia–Kalaba-like control for asymptotic convergence. Figure 11 gives the trajectories of the link angles velocities \(\mathop {\dot{q}}\nolimits^{(2)}\) and \(\mathop {\dot{q}}\nolimits^{(4)}\), respectively.

9 Conclusions

Udwadia and Kalaba departed from the conventional wisdom in distinguishing constrains into holonomic and nonholonomic by addressing second order form of constrains. As a result, an integrated framework is constructed to treat constraints. They then formulated the simplest form of equation of motion for constrained systems since 1788. The constraint force is represented in analytical (i.e., closed) form without invoking the use of Lagrange multiplier, projection method, or any quasi variables. The procedure of the Udwadia–Kalaba approach is rather straightforward. So far, the Udwadia–Kalaba Equation is the simplest and most comprehensive equation of motion for constrained mechanical systems. Due to its simplicity and closed form, the Udwadia–Kalaba Equation encompasses a wide range of applicability. It applies to a wide class of constraints, whether holonomic constraints or nonholonomic constraints, so long as they are linear with respect to the accelerations or reducible to be that form. Besides, it provides a new approach to the control design for constrained mechanical systems. We present examples to illustrate how to build the model and how to deal with the constraint. Furthermore, we demonstrate the performance of the Udwadia–Kalaba Equation via simulations. The Udwadia–Kalaba Equation has greatly contributed to address the complex constrained motion. Since the MP inverse exists in the closed-form constraint force, a high-performance computer is required when the constraints are comprehensive.

References

O Darrigol, U Frisch. From Newton’s mechanics to Euler’s equations. Physica D Nonlinear Phenomena, 2008, 237(14-17): 1855–1869.

L Hand, J Finch, R W Robinett. Analytical mechanics. American Journal of Physics, 2000, 68(68): 390–393.

J L Lagrange. Mechanique analytique. Paris: Mme ve Courcier, 1787.

R Rosenberg. Analytical dynamics of discrete systems. New York: Plenum Press, 1977.

W Greiner. Classical mechanics. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer, 2010.

J H Ginsberg. Engineering dynamics. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

P A M Dirac. Lectures in quantum mechanics. New York: Yeshiva University, 1964.

M D Ardema. Analytical dynamics. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2005.

J Köppe, W Grecksch, W Paul. Derivation and application of quantum Hamilton equations of motion. Annalen Der Physik, 2017, 529(3): 1600251.

J G Papastavridis. Analytical mechanics. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

C F Gauss. Uber ein neues allgemeines Grundgsetz der Mechanik. Journal of die reine und angewandte Mathematik, 1829, 4: 232–235.

P Appell. Sur les mouvements de roulement èquations du mouvement analogues à celles de Lagrange. CR Acad Sci Paris, 1899, 129: 317–320.

L A Pars. A treatise on analytical dynamics. London: Heinemann, 1965.

G Hamel. Theoretische mechanik. Berlin: Springr-Verlag, 1949.

F E Udwadia, T Wanichanon. Hamel’s paradox and the foundations of analytical dynamics. Applied Mathematics and Computation, 2010, 217(3): 1253–1265.

Y H Chen. Hamel paradox and Rosenberg conjecture in analytical dynamics. Journal of Applied Mechanics, 2013, 80(4): 369–384.

H Zhao, X M Zhao, J M Jiang. Study on Hamel’s embedding method via the Udwadia-Kalaba theory. Applied Mathematics and Mechanics, 2017, 38(6): 696–707.

T R Kane, D A Levinson. Dynamics, theory and applications. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1985.

T R Kane. Dynamics of nonholonomic systems. American Mathematical Society, 1972, 28(3): 199–205.

W W Rouseball. A short account of the history of mechanics. New York NY: Dover Publications, 1960.

I H Shames. Engineering mechanics: dynamics. New Jersey NJ: Englewood Cliffs, 1960.

E J Saletan, A H Cromer. Theoretical mechanics. New York NY: Wiley Press, 1971.

H Irschik, H J Holl. The equations of Lagrange written for a non-material volume. Acta Mechanica, 2002, 153(3–4): 231–248.

B Brogliato. Kinetic quasi-velocities in unilaterally constrained Lagrangian mechanics with impacts and friction. Multibody System Dynamics, 2014, 32(2): 175–216.

J W Gibbs. On the fundamental formulas of dynamics. American Journal of Mathematics, 1879, 2: 49–64.

G A Maggi. Di alcune nuove forme delle equa- zioni della Dinamica, applicabili ai sistemi anolonomi. Atti Reale Accad Lin Rend Classe Sci Fisiche, Matematiche Naturali, 1901, 5(10): 287–92.

F E Udwadia, R E Kalaba. Analytical dynamics: A new approach. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

F E Udwadia, R E Kalaba. A new perspective on constrained motion. Proceedings Mathematical & Physical Sciences, 1992, 439(1906): 407–410.

F E Udwadia, R E Kalaba. On motion. Journal of the Franklin Institute, 1993, 330(3): 571–577.

F E Udwadia, R E Kalaba. Explicit equations of motion for mechanical systems with nonideal constraints. Journal of Applied Mechanics, 2001, 68(3): 462–467.

F E Udwadia, R E Kalaba. The geometry of constrained motion. ZAMM - Journal of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics, 2015, 75(8): 637–640.

F E Udwadia. Optimal tracking control of nonlinear dynamical systems. Proceedings of the Royal Society A, 2008, 464(2097): 2341–2363.

F E Udwadia, P A Phohomsiri. Explicit equations of motion for constrained mechanical systems with singular mass matrices and applications to multi-body dynamics. Proceedings of the Royal Society, 2006, 462(2 071): 2097–2117.

Y H Chen, X R Zhang. Adaptive robust approximate constraint- following control for mechanical systems. Journal of the Franklin Institute, 2010, 347(1): 69–86.

F E Udwadia, T Wanichanon. Control of uncertain nonlinear multibody mechanical systems. Journal of Applied Mechanics, 2014, 81(4): 041020.

A M Bloch. Nonholonomic mechanics and control. New York: Springer, 2003.

F Bullo, A D Lewis. Geometric control of mechanical systems: modeling, analysis, and design for simple mechanical control systems. New York: Springer Verlag, 2005.

G Zhai, I Matsune, T Kobayashi, et al. A study on stabilization of nonholonomic systems via a hybrid control method. Nonlinear Dynamics & Systems Theory, 2007, 7(3): 327–338.

Z P Wang, S S Ge, T H Lee. Robust motion/force control of uncertain holonomic/nonholonomic mechanical systems. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics, 2004, 9(1): 118–123.

Y H Chen. Constraint-following servo control design for mechanical systems. Journal of Vibration & Control, 2009, 15(3): 369–389.

D Serre. Matrices: theory and applications. New York: Springer, 2002.

E H Moore. On the reciprocal of the general algebraic matrix. Bulletin of American Mathematical Society, 1920, 26(5): 394–395.

R Penrose. A generalized inverse for matrices. Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 1955, 51(3): 406–413.

R E Kalaba, F E Udwadia. Lagrangian mechanics, gauss’ principle, quadratic programming, and generalized inverses: new equations for nonholonomically constrained discrete mechanical systems. Quarterly of Applied Mathematics, 1994, 52(2): 229–241.

F E Udwadia, R E Kalaba. An alternate proof for the equation of motion for constrained mechanical systems. Applied Mathematics & Computation, 1995, 70(23): 339–342.

F E Udwadia, R E Kalaba, H C Eun. Equations of motion for constrained mechanical systems and the extended d’Alembert’s principle. Quarterly of Applied Mathematics, 1997, 55(2): 321–331.

F E Udwadia, R E Kalaba. What is the general form of the explicit equations of motion for constrained mechanical systems. Journal of Applied Mathematics, 2002, 69(3): 335–339.

F E Udwadia. A new perspective on the tracking control of nonlinear structural and mechanical systems. Proceedings of the Royal Society A Mathematical Physical & Engineering Sciences, 2003, 459(2035): 1783–1800.

F E Udwadia, T Wanichanon, H Cho. Methodology for satellite formation keeping in the presence of system uncertainties. Journal of Guidance, Control, and Dynamics, 2014, 37(5): 1611–1624.

F E Udwadia. A new approach to stable optimal control of complex nonlinear dynamical systems. Journal of Applied Mechanics, 2014, 81(3): 031001.

X M Zhao, Y H Chen, H Zhao. Control design based on dead-zone and leakage adaptive laws for artificial swarm mechanical systems. International Journal of Control, 2017, 90(5): 1077–1089.

H Zhao, S C Zhen, Y H Chen. Dynamic modeling and simulation of multi-body systems using the Udwadia-Kalaba theory. Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering, 2013, 26(5): 839–850.

R Y Zhao, Y H Chen, S J Jiao. Optimal design of constraint- following control for fuzzy mechanical systems. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems, 2016, 24(5): 1108–1120.

Y H Chen. Mechanical systems under servo constraints: the Lagrange’s approach. Mechatronics, 2005, 15(3): 317–337.

Y H Chen. Equations of motion of mechanical systems under servo constraints: the Maggi approach. Mechatronics, 2008, 18(4): 208–217.

Y H Chen. Approximate constraint-following of mechanical systems under uncertainty. Nonlinear Dynamics and Systems Theory. 2008, 8(4): 329–337.

R Y Zhao, Y H Chen, S J Jiao. Optimal design of robust control for positive fuzzy dynamic systems with one-sided control constraint. Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems, 2016, 32(1):1–13.

J Huang, Y H Chen, Z H Zhong. Udwadia-Kalaba approach for parallel manipulator dynamics. Journal of Dynamic Systems Measurement & Control, 2013, 135(6): 061003.

Q M Huang, Y H Chen, A G Cheng. Adaptive robust control for fuzzy mechanical systems: Constraint-following and redundancy in constraints. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems, 2015, 23(4): 1113–1126.

F F Dong, J Han, Y H Chen, et al. A novel robust constraint force servo control for under-actuated manipulator systems: Fuzzy and optimal. Asian Journal of Control, 2018, 20(5): 1–21.

X M Zhao, Y H Chen, H Zhao. Robust approximate constraint- following control for autonomous vehicle platoon systems. Asian Journal of Control, 2018, 20(6): 1–13.

J Han, Y H Chen, X M Zhao, et al. Optimal design for robust control of uncertain flexible joint manipulators: a fuzzy dynamical system approach. International Journal of Control, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1080/00207179.2017.1299945.

Authors’ Contributions

Y-HC was in charge of the whole trial; X-MZ wrote the manuscript; HZ and F-FD assisted with sampling and laboratory analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ Information

Xiao-Min Zhao, born in 1986, is currently a lecturer at School of Automotive and Transportation Engineering, Hefei University of Technology, China. She received her bachelor degree in 2009 and PhD degree in 2017 from Hefei University of Technology, China. Her research interests include system modeling, control theory, vehicle engineering.

Ye-Hwa Chen, born in 1956, is currently a professor at Georgia Institute of Technology, USA. He is a member of IEEE, ASME and Sigma Xi. He received his PhD degree from the University of California, Berkely, USA, in 1985. His research interest covers advanced control methods for mechanical manipulators, neural networks and fuzzy engineering, adaptive robust control of uncertain systems, and uncertainty management.

Han Zhao, born in 1957, is currently a vice-president and a doctoral supervisor at Hefei University of Technology, China. He is a committee member of International IFToMM Education Commission. His research interests include mechanical transmission, magnetic machine, vehicles, digital design and manufacturing, information system, dynamics and control.

Fang-Fang Dong, born in 1988, received his bachelor degree in 2009 and PhD degree in 2016 from Hefei University of Technology, China. His research interests include modeling and control of mechanical systems, robotics, fuzzy dynamical systems.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

Supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51705116), Anhui Provincial Science and Technology Major Project of China (Grant No. 17030901036), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China (Grant Nos. JZ2018HGBZ0096, JZ2018HGTA0217, JZ2018HGTB0261).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, XM., Chen, YH., Zhao, H. et al. Udwadia–Kalaba Equation for Constrained Mechanical Systems: Formulation and Applications. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 31, 106 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10033-018-0310-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10033-018-0310-x