Abstract

Aim

While proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are generally considered safe and well tolerated, frail older people who take PPIs long term may be susceptible to adverse events. This study characterized PPI use and determined factors associated with high-dose use among older adults in residential aged care services (RACSs).

Methods

A cross-sectional study of 383 residents of six South Australian RACSs within the same organization was conducted. Clinical, diagnostic, and medication data were collected by study nurses. The proportions of residents who took a PPI for > 8 weeks and without documented indications were calculated. Factors associated with high-dose PPI use compared to standard/low doses were identified using age- and sex-adjusted logistic regression models.

Results

196 (51%) residents received a PPI, with 45 (23%) prescribed a high dose. Overall, 173 (88%) PPI users had documented clinical indications or received medications that can increase bleeding risk. Three-quarters of PPI users with gastroesophageal reflux disease or dyspepsia had received a PPI for > 8 weeks. High-dose PPI use was associated with increasing medication regimen complexity [odds ratio (OR) 1.02; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.01–1.04 per one-point increase in Medication Regimen Complexity Index score] and a greater number of medications prescribed for regular use (OR 1.11; 95% CI 1.01–1.21 per additional medication).

Conclusions

Half of all residents received a PPI, of whom the majority had documented clinical indications or received medications that may increase bleeding risk. There remains an opportunity to review the continuing need for treatment and consider “step-down” approaches for high-dose PPI users.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are prescribed for regular use to one in two residents of aged care services. |

There is a need to review whether indications for PPI use are still current when prescribing these medications for residents, and clearly document when PPIs are prescribed for gastroprotection in conjunction with specific gastric irritant medications. |

The opportunity exists to “step down” therapy and deprescribe PPIs in this setting. |

1 Introduction

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are indicated for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and dyspepsia, Barrett’s esophagus, and to prevent adverse gastrointestinal effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [1,2,3,4]. An estimated 5.5% of all Australians use PPIs, with the highest prevalence of use among those aged over 80 years [5]. Internationally, there is considerable variation in the prevalence of PPI use in residential aged care services (RACSs), ranging from 14 to 93% of residents [6,7,8].

The Australian Therapeutic Guidelines and American Gastroenterological Association recommend PPI use be limited to 4–8 weeks’ duration for the symptomatic relief of uncomplicated GERD [9, 10]. If symptoms are not alleviated, the PPI dose may be increased or administered twice daily until symptoms are adequately controlled [10, 11]. However, periodic reassessment of the possibility to reduce the dose to the lowest effective dose once symptom relief is achieved is recommended. Long-term PPI use is not recommended for symptomatic relief of uncomplicated symptoms without further investigation, particularly if dose reduction or cessation is unsuccessful [9,10,11]. However, prophylactic PPI use may be suitable for older people at high risk of an ulcer who take concomitant gastric irritant medications such NSAIDs, including aspirin [10]. Medications for symptom relief, such as PPIs, should also be routinely reviewed in people living with dementia because people living with dementia may under-report both disease-related symptoms and medication side effects [12].

Proton pump inhibitors are considered generally safe and well tolerated medications with infrequent adverse events. However, vitamin B12 deficiencies, hypomagnesaemia, Clostridium difficile infection, community-acquired pneumonia, fractures, and renal injury have been associated with PPI use [13]. Much of the evidence for these and other adverse events is limited or inconclusive. Nevertheless, frail older residents may be at increased risk of experiencing adverse events, particularly if high-dose PPIs are prescribed. Given the high prevalence of PPI use in RACSs, even rare adverse events may affect large numbers of residents [14].

Existing literature suggest older people may be prescribed PPIs for long periods and without clear indications for use [6]. Few studies have assessed duration of PPI use among residents of RACSs and whether residents have documented clinical indications for PPI use. A previous study utilizing data collected from 22 skilled nursing facilities in the USA found that one-quarter of residents prescribed a PPI did not have a valid indication for use and were not taking a concomitant NSAID or anticoagulant [7].

There is increasing focus on regularly reviewing the need for PPI treatment in older people. Over the last decade, multiple national quality improvement initiatives directed at healthcare professionals and consumers have been implemented to improve PPI use in Australia [14]. As part of the Choosing Wisely Australia initiative, the Gastroenterological Society of Australia and the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners both recommend that PPIs are not prescribed long term without attempting to reduce to the lowest possible dose or ceasing the PPI [15]. The objective of this study was to characterize PPI use. We also determined factors associated with high-dose PPI use among older adults in RACSs.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design, Setting, and Participants

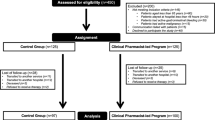

A secondary analysis of cross-sectional data collected from residents of six South Australian RACSs was undertaken. Five of the RACSs were located in metropolitan Adelaide and one was located in a regional center. RACSs provide assisted accommodation for people with care needs that can no longer be met at home [16]. RACSs are synonymous with nursing homes and long-term care facilities in other countries. The study methods and characteristics of the cohort have been previously described [17]. Briefly, adults aged 65 years or older were recruited between April and August 2014. Residents who were considered medically unstable (e.g., experiencing delirium) and residents with an estimated life expectancy of less than 3 months were excluded. Of the 664 residents in the 6 RACSs, 603 were invited to participate. Among the invited residents, 34 were excluded as the resident was medically unstable, hospitalized, or receiving palliative care, and a further 25 residents were excluded for other reasons. There were 106 residents who declined to participate and third-party consent could not be arranged for a further 54 residents. The final cohort comprised 383 residents. Participating residents were similar to all residents of the six RACSs in terms of age (mean age 87.5 years among participating residents vs. 87.3 years in all residents of the six RACSs), sex (77.5% female vs. 78.5% female) and diagnosed dementia (44.1% vs. 46.8%).

2.2 Data Collection

Data collection was undertaken by three study nurses who had been trained in the administration of the tools. Data collected included activities of daily living (ADLs) measured with the six-item Katz ADL index [18] and behavioral symptoms were assessed using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Nursing Home version (NPI-NH) [19]. Dementia severity was assessed using the 12-item Dementia Severity Rating Scale (DSRS) [20] and frailty was screened using the seven-item FRAIL-NH scale [21]. Residents’ attitudes towards deprescribing were measured using the ten-item Patients’ Attitude Towards Deprescribing (PATD) tool [22]. The ADL, NPI-NH, and DSRS scales were completed in conjunction with a staff informant who had known the resident for at least 2 weeks. Diagnostic data were identified from the RACS electronic medical records. Charlson’s Comorbidity Index (CCI) was calculated for each resident [23]. The CCI consolidates individual coexisting medical diagnoses into a single, predictive variable.

2.3 Medication Use

Medication administration charts for each resident were collected by study nurses on the day of study entry and reviewed by the research team. Each chart contained details of the medication name, dose form, strength, and administration frequency. Medications were defined as all prescription and non-prescription medications including topical preparations and nutritional and herbal supplements. The medication charts documented all medications prescribed on the day of study entry, and this was the primary exposure of interest for the present study; however, the history of medication prescribing prior to study entry available from each chart ranged from 1 day to more than 1 year prior to the date of data collection. This was because the medication charts were valid for use for up to several months once the chart was in use and the prescriber can choose to record the date a medication was first prescribed on the medication chart. Regular use was defined as the use of medications that were prescribed to be taken at regular intervals and written on the regular administration section of the medication chart. Regular use did not include medications listed in the pro re nata (PRN or “when required”), short-term use or nurse-initiated sections of the medication administration chart. Medication data were extracted from each chart and medications were classified using the World Health Organization (WHO) Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system [24].

For the present cross-sectional study, details of all PPIs prescribed on the day of study entry for each resident were extracted for analysis. However, for all residents prescribed a PPI on the day of study entry, we also examined a copy of the medication chart collected on the day of study entry to identify if the duration of PPI use prior to study entry exceeded 8 weeks. PPIs were defined as pantoprazole (ATC code A02BC02), esomeprazole (A02BC05, A02BD06), lansoprazole (A02BC03), omeprazole (A02BC01), and rabeprazole (A02BC04). The criteria used to define low-, standard-, and high-dose PPI use are presented in Table 1, and were consistent with dosing recommendations in Australia’s national formulary [11]. Long-term PPI use was defined as use greater than a period of 8 weeks from the date first prescribed (where documented on the current medication chart) or when duration of use shown on the current medication administration chart was greater than 8 weeks. Use of gastric irritant medications or medications associated with increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding were defined as regular use of an NSAID (ATC code M01AB, M01AC, M01AE, M01AG, M01AH), aspirin (B01AC06, B01AC30, N02BA01), warfarin (B01AA03), apixaban (B01AF02), rivaroxaban (B01AF01), or dabigatran (B01AE07). Medication regimen complexity was calculated using the 65-item validated Medication Regimen Complexity Index (MRCI) [25]. The MRCI incorporates a weighting corresponding to dosage form used, dosage frequency, and additional directions, with higher MRCI scores corresponding with more complex medication regimens.

2.4 Main Outcome Measures

The main outcome measures included the proportion of residents receiving a PPI and the dose prescribed. We investigated factors associated with high-dose PPI use compared to standard/low-dose PPI use. We further investigated the duration of PPI use (greater than 8 weeks) and whether there was an indication consistent with PPI use (GERD, esophagitis, dyspepsia, Barrett’s esophagus, peptic ulcer disease, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, gastritis, or Helicobacter pylori) documented in the resident’s current medical history. Concomitant, regular use of gastric irritant medications or medications associated with increased bleeding risk on the day of study entry was also determined from medication administration charts.

2.5 Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize resident characteristics, PPI use, and treatment. Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare continuous variables with skewed distributions, t tests were used to compare continuous variables that were normally distributed, and Chi square tests were used to compare categorical variables. Logistic regression models were used to determine unadjusted and age- and sex-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for associations between demographic, clinical, and medication-related factors and high-dose PPI use (vs. use of low/standard PPI dose). Multiple imputation with five iterations was used to impute missing values for ADL score (1.3% missing) and FRAIL-NH score (1.0% missing) for the age- and sex-adjusted regression models. P values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All data were analyzed using SAS software v 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

2.6 Compliance with Ethical Standards

This study was approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee and the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners National Research and Evaluation Ethics Committee. The study was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained for all residents participating in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the resident’s guardian, next of kin, or significant other when a resident was unable to provide informed consent.

3 Results

The 383 residents who participated in this study had an average age of 88 years, 76% were female, and 44% had a documented diagnosis of dementia (Table 2). The characteristics of residents who did and did not receive a PPI are compared in Table 2.

There were 196 (51%) residents who were prescribed a PPI. Of these, seven residents (3.6% of residents receiving a PPI) were prescribed a low-dose PPI, 143 (73.0%) received a standard dose and 45 (23%) residents received a high-dose PPI (Table 3). Pantoprazole and esomeprazole together represented approximately 80% of PPI use. Twice-daily administration was identified for 21 residents (10% of PPI users). The PPI was prescribed for regular use for all 196 residents, with no residents prescribed PRN PPIs.

Overall, 145 (74%) residents receiving a PPI had at least one documented clinical indication for PPI use, of which the most frequent was GERD (Table 3). Approximately half of all residents (55%) prescribed a PPI were also prescribed one or more medications associated with gastric irritation or increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. Neither an indication nor a medication associated with increased bleeding risk or gastric irritation was identified for 23 (12%) residents prescribed a PPI.

Among the 196 residents who received a PPI, the duration of PPI prescribing could be established for 147 (75%) residents based on the current medication chart. A PPI was taken for longer than 8 weeks in almost all residents (n = 141, 96%) where the current medication chart included at least 8 weeks of PPI prescribing data. Of the 124 residents with documented GERD or dyspepsia who were prescribed a PPI, 123 residents had sufficient information recorded on the medication chart to assess whether the PPI had been prescribed for more than 8 weeks, and three-quarters (n = 93, 76%) had received a PPI for more than 8 weeks (Table 3).

Overall, 142 (72%) residents receiving a PPI were able to self-report their willingness for medications to be deprescribed. Of these, few residents (8%) were comfortable with the number of medications taken and most residents (83%) indicated a willingness to stop one or more regular medications if their doctor said it was possible (Table 4).

Characteristics associated with high-dose PPI use compared to low or standard doses are shown in Table 5. A greater number of medications prescribed for regular administration and increasingly complex medication regimens were significantly associated with the use of a high-dose PPI. High-dose PPI use was not found to be associated with dementia, frailty, independence in ADLs, or increased NPI-NH scores in the age- and sex-adjusted analyses.

4 Discussion

This study characterizing PPI use in 6 Australian RACSs showed that half of all residents receive a PPI on a regular basis. Our study findings are consistent with other research in RACSs suggesting that PPI use is highly prevalent [6,7,8]. Furthermore, our finding that residents taking high-dose PPIs had high levels of polypharmacy and medication regimen complexity compared to low/standard-dose users is consistent with previous RACS research that found PPIs were taken by 72% of residents receiving nine or more regular medications compared to 36% receiving fewer than nine medications [26]. Previous research has predominantly investigated prevalence of PPI use in RACSs using defined daily doses or without assessing dose. We found that three in four residents who took a PPI received a standard dose. Less than 4% of residents who took a PPI received a low-dose PPI. It is also important for prescribers to document the indication and intended duration when prescribing a PPI for a resident of an aged care service. Nearly nine in ten residents taking a PPI had a documented indication consistent with PPI use. However, three-quarters of residents with GERD or dyspepsia charted a PPI had taken the PPI for more than 8 weeks. These findings are similar to a recent Canadian study involving 147 residents who were prescribed a PPI, of whom 62% of residents with GERD had received the PPI for more than 8 weeks, and one in five residents taking a PPI had no documented indication for PPI use [27].

Our findings suggest that stepping-down therapy to lower doses may be appropriate for up to one-quarter of residents who received a high-dose PPI. The finding that many residents with GERD or dyspepsia had received a PPI for more than 8 weeks also suggests there are opportunities for stepping-down therapy. Further, residents who took PPIs long term without an apparent indication and residents with documented dyspepsia or GERD who had received a PPI for more than 8 weeks may be suitable candidates for deprescribing [6, 28]. Deprescribing refers to “reducing medications after consideration of therapeutic goals, benefits and risks, and medical ethics” [29]. Deprescribing PPIs can be challenging, as abrupt cessation may result in rebound symptoms, possibly due to acid hypersecretion [30, 31]. Deprescribing for residents living with dementia can also be complicated by medical practitioner and systems-related barriers such as lack of time or resources, or fear of negative consequences [32]. Difficulties with decision-making, comprehension, and communication among residents with dementia may also limit deprescribing [32]. However, in our study, the residents’ willingness to consider deprescribing indicates that it may be feasible in this population to attempt PPI dose de-escalation or deprescribing. Residents taking PPIs in the present study also had high levels of polypharmacy and medication regimen complexity, and therefore could potentially benefit from deprescribing. Translational research could test and implement targeted strategies for stepping-down therapy among residents receiving high-dose PPIs and for deprescribing PPIs prescribed for treating GERD or dyspepsia for more than 8 weeks. This process could be informed by recommendations from both the Canadian guidelines for deprescribing PPIs and a recent systematic review [28, 33], and known resident, caregiver, and prescriber facilitators and barriers to deprescribing, particularly in people with dementia [34, 35], as well as previous deprescribing controlled trials in RACSs. Interdisciplinary approaches may be more likely to facilitate the optimization of PPI use among older people. For example, previous Australian research has indicated that repeated multifaceted quality improvement interventions targeting clinicians and older veterans taking a PPI to encourage PPI dose reductions have achieved sustained improvements in PPI use [14].

Study strengths include investigation of PPI use in RACSs, including medication selection and dose, within a modest sample size of residents. Our sample included residents from metropolitan and rural areas and was representative of all residents in the six RACSs from which the participating residents were recruited. The six RACSs were maintained by the same aged care provider organization, and therefore findings may not be generalizable to all Australians receiving residential aged care services. In Australia, 59% of residents of aged care services are aged 85 years and over, 68% of residents are female, and 52% of residents are living with dementia [36, 37].

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to investigate guideline-appropriate PPI use in RACSs that has considered PPI dose and duration. Because only three-quarters of residents receiving a PPI had medication charts with more than 8 weeks of prescribing data available, our study may have underestimated the proportion of residents using PPIs for longer than 8 weeks. The cross-sectional nature of this study also meant we could not assess causation or changes in PPI use over an extended period. We were unable to reliably assess previous attempts at dose changes or withdrawals as while we could extract the date the PPI was prescribed from some medication charts, we lacked continuous information on PPI dose and administration for all residents prior to study entry. We were also unable to determine the circumstances under which the PPI was originally prescribed and any adverse events experienced by study participants. Although older age is a risk factor for gastrointestinal bleeding associated with NSAIDs or anticoagulants [10], we were unable to determine whether PPI prophylaxis was warranted for all residents who received a gastric irritant medication or a medication associated with increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. There was also a small number of residents taking a PPI with a diagnosis of gastritis recorded in the medical history, and this was defined as a potential indication for PPI use in this study. We recognize that gastritis may not be an approved indication for PPI use in all settings, and therefore the proportion of residents who had at least one documented clinical indication for PPI treatment may be slightly overestimated. Finally, we explored associations using age- and sex-adjusted models, but our modest sample size prevented exploration using multivariable models, and therefore residual confounding may still exist.

5 Conclusions

Despite PPI use being highly prevalent, many residents taking a PPI had documented clinical indications for treatment. This is contrary to the popular belief that PPIs should be targeted for deprescribing due to lack of clear clinical indications in RACSs and could be further explored in future studies. However, there remains an opportunity to review the continuing need for PPI use among residents with GERD who are treated for more than 8 weeks, and identify if residents using higher PPI doses are suitable for “step-down” approaches to treatment. There is also a need for clinicians to specify when PPIs are prescribed for gastroprotection and clearly document whether indications for PPI use are still current.

References

Boparai V, Rajagopalan J, Triadafilopoulos G. Guide to the use of proton pump inhibitors in adult patients. Drugs. 2008;68:925–47.

Savarino V, Di Mario F, Scarpignato C. Proton pump inhibitors in GORD. An overview of their pharmacology, efficacy and safety. Pharmacol Res. 2009;59:135–53.

El-Serag H, Becher A, Jones R. Systematic review: persistent reflux symptoms on proton pump inhibitor therapy in primary care and community studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:720–37.

Latimer N, Lord J, Grant RL, O’Mahony R, Dickson J, Conaghan PG. Cost effectiveness of COX 2 selective inhibitors and traditional NSAIDs alone or in combination with a proton pump inhibitor for people with osteoarthritis. BMJ. 2009;339:b2538.

Hollingworth S, Duncan EL, Martin JH. Marked increase in proton pump inhibitors use in Australia. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19:1019–24.

Sluggett JK, Hendrix I, Bell JS. Evidence-based deprescribing of proton pump inhibitors in long-term care. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2018;14:124–6.

Patterson-Burdsall D, Flores HC, Krueger J, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors with lack of diagnostic indications in 22 Midwestern US skilled nursing facilities. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14:429–32.

Teramura-Grönblad M, Bell JS, Pöysti MM, et al. Risk of death associated with use of PPIs in three cohorts of institutionalized older people in Finland. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:488.e9–13.

Freedberg DE, Kim LS, Yang YX. The risks and benefits of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: expert review and best practice advice from the American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:706–15.

Gastrointestinal Expert Group. Therapeutic guidelines: gastrointestinal, version 6. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Limited; 2016.

Rossi S, editor. Australian medicines handbook. Adelaide: AMH Pty Ltd; 2018.

Page AT, Potter K, Clifford R, McLachlan AJ, Etherton-Beer C. Medication appropriateness tool for co-morbid health conditions in dementia: consensus recommendations from a multidisciplinary expert panel. Intern Med J. 2016;46:1189–97.

Maes ML, Fixen DR, Linnebur SA. Adverse effects of proton-pump inhibitor use in older adults: a review of the evidence. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2017;8:273–97.

Pratt NL, Kalisch Ellett LM, Sluggett JK, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors among older Australians: national quality improvement programmes have led to sustained practice change. Int J Qual Health Care. 2017;29:75–82.

Choosing Wisely Australia. 2018. http://www.choosingwisely.org.au/recommendations. Accessed 13 Nov 2018.

Sluggett JK, Ilomäki J, Seaman KL, Corlis M, Bell JS. Medication management policy, practice and research in Australian residential aged care: current and future directions. Pharmacol Res. 2017;116:20–8.

Tan ECK, Visvanathan R, Hilmer SN, et al. Analgesic use, pain and daytime sedation in people with and without dementia in aged care facilities: a cross-sectional, multisite, epidemiological study protocol. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005757.

Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged: the index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–9.

Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The neuropsychiatric inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–14.

Clark CM, Ewbank DC. Performance of the dementia severity rating scale: a caregiver questionnaire for rating severity in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1996;10:31–9.

Kaehr E, Visvanathan R, Malmstrom TK, Morley JE. Frailty in nursing homes: the FRAIL-NH scale. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:87–9.

Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Development and validation of the patients’ attitudes towards deprescribing (PATD) questionnaire. Int J Clin Pharm. 2013;35:51–6.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83.

World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. ATC/DDD Index 2018. 2018. http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/. Accessed 9 July 2018.

George J, Phun YT, Bailey MJ, Kong DCM, Stewart K. Development validation of the medication regimen complexity index. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:1369–76.

Jokanovic N, Jamsen KM, Tan ECK, Dooley MJ, Kirkpatrick CM, Bell JS. Prevalence and variability in medications contributing to polypharmacy in long-term care facilities. Drug Real World Outcomes. 2017;4:235–45.

Doell A, Walus A, To J, Bell A. Quantifying candidacy for deprescribing of proton pump inhibitors among long-term care residents. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2018;71:302–7.

Wilsdon TD, Hendrix I, Thynne TRJ, Mangoni AA. Effectiveness of interventions to deprescribe inappropriate proton pump inhibitors in older adults. Drugs Aging. 2017;34:265–87.

Turner JP, Edwards S, Stanners M, Shakib S, Bell JS. What factors are important for deprescribing in Australian long-term care facilities? Perspectives of residents and health professionals. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e009781.

Reeve E, Andrews JM, Wiese MD, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Shakib S. Feasibility of a patient-centered deprescribing process to reduce inappropriate use of proton pump inhibitors. Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49:29–38.

Reeve E, Hilmer S. Tapering or abrupt cessation of proton pump inhibitors? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73:923–4.

Reeve E, Bell JS, Hilmer SN. Barriers to optimising prescribing and deprescribing in older adults with dementia: a narrative review. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2015;10:168–77.

Farrell B, Pottie K, Thompson W, et al. Deprescribing proton pump inhibitors: evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:354–64.

Anderson K, Stowasser D, Freeman C, Scott I. Prescriber barriers and enablers to minimising potentially inappropriate medications in adults: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e006544.

Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, Shakib S, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2013;30:793–807.

Aged care data snapshot–2017. 2018. https://www.gen-agedcaredata.gov.au/Resources/Access-data/2018/January/Aged-care-data-snapshot%E2%80%942017. Accessed 16 May 2019.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s welfare 2017. Australia’s welfare services no. 13. AUS 214. Canberra: AIHW; 2017.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Resthaven management team, research nurses, facility staff, residents, and family members for their valuable support and participation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Centre of Research Excellence in Frailty and Healthy Ageing and the NHMRC Cognitive Decline Partnership Centre. Data used for this study were collected with support from the Alzheimer Australia Dementia Research Foundation via the Resthaven Incorporated Dementia Research Award, with additional funding provided by Resthaven Incorporated. ECKT is supported by an NHMRC-ARC Dementia Research Development Fellowship. JSB is supported by an NHMRC Boosting Dementia Research Leadership Scheme Fellowship. JKS is supported by an NHMRC Early Career Fellowship.

Conflict of interest

TC and LR are employees of Resthaven Incorporated and RV is a member of the board of Resthaven Incorporated.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hendrix, I., Page, A.T., Korhonen, M.J. et al. Patterns of High-Dose and Long-Term Proton Pump Inhibitor Use: A Cross-Sectional Study in Six South Australian Residential Aged Care Services. Drugs - Real World Outcomes 6, 105–113 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-019-0157-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-019-0157-1