Abstract

We report a phase inversion polymer coating as a novel concept with potential to prevent clay swelling and fines generation in coal seam gas, or other petroleum, wellbores. Our approach uses polyethersulfone (PES) with N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) as a water-soluble solvent to form a dense, low-porosity film across the clay-rich interburden layers, but a porous and permeable membrane on coal seams. This contrasting behaviour occurs because the coal contains much more free water than the clay-rich interburden layers. We demonstrate the efficacy of the method to prevent clay spalling in immersion tests and under a flow of fresh water in a visual swell test apparatus. The clay-rich rocks studied were mudstone and siltstone, and these were dip coated in the PES/NMP solution. The uncoated mudstone swelled and broke apart quickly in the immersion test and visual flow test, but the PES coated rock samples were stable for 30 days. The coated rock and coal samples were characterised by X-ray diffraction, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and scanning electron microscopy. The morphology of coated mudstone and coated coal samples showed that the polymer formed a dense layer across the low-permeability mudstone, but an open porous structure on the coal surface. The effect of the coating on the permeability of KCl brine through coal was measured in a core-flood apparatus. Although the permeability of the coal showed some deterioration after coating, from (0.58 ± 0.12) mD to (0.3 ± 0.03) mD, these results demonstrate the potential of a smart polymer coating to prevent clay swelling while remaining permeable to gas and water on coal layers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The hydration and swelling of clay-rich strata upon contact with water-based drilling fluids and low salinity formation waters presents challenges in drilling and production activities in many unconventional oil and gas fields, including shale-gas and coal seam gas (CSG) fields. Clay swelling can result in well bore instabilities that lead to (1) cave-ins, tight holes and other problems while drilling or running casing, and (2) spalling and sloughing of solids into the well during production that can damage down hole pumps and may impact the operation of surface facilities (Towler et al. 2016). Further from the well bore, the swelling and migration of clays in coal cleat networks can plug pore throats and have negative impacts on the reservoirs permeability (Bai et al. 2015; Yao et al. 2016), which is also an important topic but in our current study we are focused on the generation of fines at the wellbore.

Water-reactive shales are reported to be present in more than 75% of all formations drilled across the world (Anderson et al. 2010; Dzialowski et al. 1993; Peng et al. 2013). In CSG wells drilled in the Surat Basin of Queensland Australia the problems associated with clay-swelling are exemplified in open-hole completions across multiple thin coal seams (commonly less than 1 m thick Hamilton et al. 2014) and clay-rich interburden layers. Although interburden in each formation will have unique sets of properties, typically sedimentary shale rocks are composed of quartz, feldspar, mica, and around 60% clay minerals such as kaolinite, smectite, illite and chlorite (Shaw and Weaver 1965). Kaolinite, illite and chlorite do not show significant swelling in contact with water. In contrast, the smectites are widely known in the petroleum industry to be the swelling clays (Velde 1992) that lead to formation damage and well bore instability. The mechanism of clay swelling when the clay is exposed to fresh water or low salinity water during drilling and production operations can be attributed to surface hydration and osmotic swelling (Darley and Gray 1988; Fink 2011).

Various chemicals and technologies known as clay stabilisers have been employed to control clay swelling in oil and gas reservoirs. In this context, a clay stabiliser acts to prevent exfoliation of clay platelets by enhancing the attractive charge between the clay layers. The most commonly used clay stabilisers are inorganic brines (KCl, NaCl and CaCl2) that work to neutralise the electrostatic repulsion between two negatively charged clay platelets (Hower 1977). In recent years, the use of organic polymers and surfactants with appropriate functional groups that interact with clays have been favoured to reduce clay swelling in conventional sandstone formations (Anderson et al. 2010). However, there has been limited application of polymers in CSG wells with open-hole completions because of cost and concerns that polymers may gum the coal layers and lead to reduced coal permeability.

Currently in CSG wells drilled in the Surat Basin the typical clay stabilisation strategy is to use drilling fluids containing 4 wt% KCl. This approach has been demonstrated for many years in different reservoir types. However, there are some limitations associated with these stabilisers either because their effectiveness typically only lasts for a short period once the CSG well is in production and being continuously flushed with fresh water, or because the treatments are sensitive to pH and temperature changes (Anderson et al. 2010). Several research teams (Baird and Walz 2006; Jung et al. 2011; Pham and Nguyen 2014) have proposed the use of nanoparticles in drilling muds or injected into reservoirs to control swelling clay and fines generation in sandstone formations, but the mechanisms by which nanoparticles control clay swelling are obscure and nanoparticle technology is currently too costly for widespread application in onshore CSG fields.

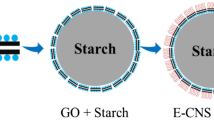

In this study, we introduce a surface-selective phase inversion polymer coating as a new approach to mitigate clay swelling in open-hole CSG wells. The concepts from chemical processes used to manufacture membrane coatings are adopted here to develop a phase inversion polymer coating binds to clay-rich interburden but remains permeable to gas and water flow on coal layers. The phase inversion process uses a controlled liquid–liquid demixing process to separate an otherwise stable polymer solution into a polymer-rich and a polymer-lean phase that forms the matrix and the pores of the polymer film (Schäfer et al. 2005; Schweizer and Kistler 2012; Strathmann and Kock 1977). Phase inversion has been used to fabricate filtration membranes with controlled film pore structure, but has not been adapted for oil and gas well bore stabilization. Figure 1 illustrates how the phase inversion concept may be applied to mitigate fines production in a CSG well. In our concept, the phase inversion polymer synthesis approach with a water-soluble solvent is used to form a low-porosity dense skin layer across clay-containing interburden layers. We selected PES as the polymer because of its low cost, superior film forming ability, good mechanical properties, strong chemical and thermal stabilities, and its resistance to acids and alkalis (Parker et al. 2000). In the results, we observed that this polymer coating reduced clay fines production from two interburden rock samples, but formed a porous membrane coating on a coal sample.

2 Experimental methods

2.1 Interburden and coal samples

We simulated in laboratory experiments fines generation from interburden mudstone and shaley siltstone using cut rocks in immersion and flowing cell tests. These experiments were designed to evaluate the potential of the selective polymer screening method to reduce the volume of fines produced at the well bore surface, and are not intended to replicate in-situ conditions in the reservoir away from the well bore. Two cored samples of clastic interburden rock from wells in the Surat Basin, Queensland Australia were selected as examples of potential source rocks for fines production in CSG wells: (1) a mudstone from a depth of 917.6 m in a North Surat well and (2) a shaley siltstone from a depth of 640.0 m in a Central Surat well. Figure 2 shows photographs of each rock sample cut from 2.5 inch cores to quarter discs approximately 3 mm thick and 15 mm radial length.

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of ground mudstone and siltstone samples collected on a Bruker Advanced X-Ray Diffractometer (40 kV, 30 mA) with Cu Kα (λ = 0.15406 nm) are shown in Fig. 3. The siltstone sample was mainly quartz (SiO2) and clay minerals. The clay minerals observed in the siltstone XRD pattern are a mixture of kaolinite (Al2Si2O5(OH)4), montmorillonite ((Na,Ca)0.33(Al,Mg)2(Si4O10)(OH)2·nH2O) and illite [Kx(Al,Mg)4(Si,Al)8O2 (OH)4·nH2O, with x < 1], but the main clay mineral is kaolinite. In addition, traces of potassium feldspar (KAlSi3O8), and goethite (a-Fe2O3·H2O) are identified. This composition is consistent with fines that have been collected by CSG operators at wellhead separators and pumps during workovers. The XRD pattern of the mudstone sample shows a larger montmorillonite signal than the siltstone XRD, indicative of a larger content of swelling clays and higher swelling potential.

The permeability tests were performed on a coal sample from the Dawson Mine, Queensland. This is a Permian-aged coal from the Baralaba coal measures in the Bowen Basin. The coal was cut to a 15 mm cube, wrapped in plastic and stored at 4 °C in a refrigerator until required for experiments.

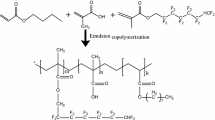

2.2 Dip-coating of PES on interburden rock samples

The polymer solution was prepared with a 1:3 weight ratio of polyethersulfone (PES, Radel A-300, Solvay Advanced Polymers) dissolved in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP). The polymer coating procedure, illustrated in Fig. 4, was: (a) sample dipped in PES/NMP solution for 1 min; (b) sample transferred to a beaker of water in which the NMP solvent is extracted from the PES phase to the water phase to leave a solid PES film on the rock, and (c) PES-coated rock removed from the water and dried in air. As the NMP is extracted into the water the PES solidifies as a polymer layer on the sample surface.

The coated rock samples were characterised by X-ray diffraction (Bruker Advanced X-Ray Diffractometer as above), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR FT-IR, PerkinElmer Spectrum 100 spectrometer) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JEOL JSM7100 operated at 20 kV). The SEM was coupled with an Oxford SDD energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS), which was used for elemental analysis of the fines collected from the visual flow cell.

2.3 Immersion tests with time lapse photography

Fines were generated from the natural and PES-coated mudstone and siltstone samples by (1) immersion of the rocks in deionised (DI) water for 30 days, and (2) by flowing fresh water past the rocks in a purpose built flow-cell (Fig. 5). The rock samples were dried under vacuum prior to immersion in distilled water. In the immersion tests, we observed spalling and dispersion of fines from the rock surfaces using digital time-lapse photography (15 megapixel Logitech camera) with photographs recorded of the rocks before exposure to the fluid and then at regular intervals for up to 30 days.

We also observed the spalling and dispersion of particles produced from mudstone and siltstone exposed to fresh water in a purpose build flow-cell (Fig. 5) using a digital camera (15 megapixel Logitech camera). The uncoated or PES-coated samples were placed in the 8 cm × 5.4 cm× 2.5 cm flow cell and a constant flow of 17 mL/min deionised water (DI) was circulated past the sample using a peristaltic pump (LongerPumpTM BT-100-2J). Samples were collected periodically from the circulating water for particle size and concentration analysis. Particle size analysis was performed with a Multisizer 4e Beckman-Coulter Counter using 25 or 50 mL of sonicated solution collected from the flow-cell system, diluted with 100–175 mL of Beckman-Coulter Isoflow electrolyte. The analysis volume in each Coulter Counter run was 500 or 1000 μL. The default of 400 bins was used with a logarithmic expanding bin size. Each size analysis measurement was repeated three times with the average particle and volume size distribution collected in each measurement. A blank solution was prepared by circulating water through the flow-cell without a rock sample and the particle size results from this blank were subtracted from fines profiles measured for the rock samples.

2.4 Measurement of permeability of coal coated with the PES polymer

The permeability the Dawson Mine coal cube before and after PES-polymer coating was measured using 4 wt% KCl brine in a Hassler-type cell (modified to hold cubic rock samples) at a confining pressure (gauge) of 20 bar and an inlet pore pressure of 5 bar. The permeability direction was parallel to the coal bedding plane. A schematic of the core flooding apparatus is shown in Fig. 6. The brine was injected by a fully automated ISCO-Teledyne 260D syringe pump, the confining fluid pressure was generated with an Enerpac hand pump, and the outlet pressure was controlled with an Equilibar back pressure regulator. The upstream and downstream fluid pressures were measured by pressure transducers with a resolution of ± 0.01 bar (Gems 3200). Permeability measurements were performed at ambient lab temperatures of (22 ± 1) °C.

The brine permeability, k, was calculated using Darcy’s Eq. (1) after the system reached an equilibrium flowrate:

where Qp is the pump flow rate (m3/s), μl is the liquid viscosity of 0.00090 Pa s, L is the sample length (m), S is the sample cross-sectional area (m2).

After measurement of the initial permeability, the coal was removed from the core holder and the face of the coal cube that was at the downstream side of the core holder was dipped in the PES/NMP solution. The PES/NMP coated coal was then re-inserted to the core holder and a confining pressure of 20 bar was re-established. Then the downstream side of the core was back filled with water to initiate the phase inversion process and replicate how this procedure may be deployed in a well. Finally, brine was injected at 5 bar again through the core in the direction from the uncoated coal face to the PES-coated face (which represents the well bore wall) and the permeability was recalculated.

3 Results and discussions

3.1 Characterisation of polymer coating

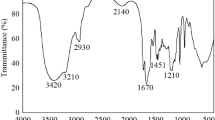

The XRD patterns in Fig. 7 show the PES polymer is mainly amorphous with one prominent diffraction peak around 2θ = 18 , which is attributed to the pure PES polymer (Guan et al. 2005; Khayet and García-Payo 2009), and that the diffraction patterns remain unchanged after coating on interburden rock and coal. Figure 8 presents ATR–FTIR spectra of the PES coating layer. The FTIR spectrum shows characteristic infrared bands at around 560 cm−1 (SO2 scissors deformation), 1151 and 1175 cm−1 (SO2 symmetric stretch), 1244 cm−1(Aryl-O-aryl C–O stretch), 1294 and 1325 cm−1 (SO2 asymmetric stretch) and 3000–3200 cm−1 (Aromatic CH stretches), which are well matched with literature references (Guan et al. 2005).

3.2 Evaluation of polymer coating effectiveness on fines generation

In a well that is being treated, the clay rich interburden is effectively impermeable to water, so the first production water that the coating encounters is on the well side. We simulate this with the dip coated samples which are then exposed to water. The phase separation first occurs at the external surface of the polymer as the solvent NMP is extracted into the water, and then slowly proceeds towards the inner polymer/rock interface by diffusion resulting in dense polymer layer. Figure 9 shows the cross-sectional morphology of polymer coating layer on the interburden sample. The thickness of coating layer is around 800 microns and the hierarchical pore structure is observed in Fig. 9a. The polymer layer on the external surface (region 1) where the water quickly extracts the NMP, is highly porous with pore size up to several microns (magnified in Fig. 9b). In contrast, the polymer layer near the interburden surface (region 2) is much denser (magnified in Fig. 9c, d). The dense layer resists water penetration into the interburden, thereby mitigating clay swelling and fines production.

To investigate the effect of the polymer coating on clay stability when exposed to water, we compared the material with and without coating, before and after exposure to water. The samples were wetted by immersion under DI water in a moderate vacuum for approximately 1 h followed by an atmospheric pressure soak for 30 days. The initial vacuum was to assist with any degassing that might occur from the samples. During the saturation period, the degree of disaggregation was recorded photographically. Figure 10 shows that after 30 days immersion the uncoated rock had disintegrated with many fine particles dispersed in the solution, but the PES coated rock remained intake during the immersion test.

The stability of the PES coating on interburden is further demonstrated in the flow cell, with example photographs captured with the video camera shown in Fig. 11 provides a visual comparison of fines generation of uncoated and polymer coated Interburden-M sample using flowing DI water . The swelling and breakage of particles from the uncoated sample swelling was apparent after just a few minutes, with the water becoming turbid. After an hour the uncoated sample had fallen apart into random shapes and small particles. In contrast, polymer coated sample under the same conditions was quite stable, and only a small amount of particles could be observed even after several days of water crossflow. These are attributed to defects of coating layer. Similar observations also apply to Interburden-S. Swelling and spalling of Interburden-S were not apparent but an increase in turbidity of the circulating water indicates the formation of large amount of solid fines. Compared to Interburden-M, Interburden-S has a smaller amount of swelling clays (as shown in Fig. 3).

The produced fines were quantified using Coulter Counter analysis of particles collected in the circulated water; and the normalised fines production reported as volume of fines per exposed surface area are presented in Fig. 12. Fines produced from the uncoated mudstone Interburden-M (Fig. 12a) increased sharply from 10 mL/m2 at the first measurement time to 58 mL/m2 after 2 h exposure to DI water, and then more gradually to more than 100 mL/m2 after 72 h. We stopped the uncoated interburden experiment after 72 h because the sample had almost completely disintegrated. The effectiveness of the PES coating to prevent swelling and spalling of the mudstone is evident in Fig. 12a where only 11 mL/m2 of fines were generated after 168 h. We observe a similar trend with the uncoated and PES coated siltstone Interburden-S (Fig. 12b), but the total amount of fines produced from the uncoated siltstone is much lower than from the mudstone because the siltstone contains fewer swelling clays than the mudstone.

Analysis of the fines produced in the DI water flow tests show that the particles from the interburden samples are mostly smecitite group minerals (SEM-EDX, Fig. 13), which may include montomorillonite, beidellite, vermiculite and saponite, and some quartz. Although quartz is not a swelling clay, when the binding clay minerals swell and break the non-swelling components such as quartz were also released from the rock composite. We noted also that the particles collected from the uncoated interburden samples were coarser than those collected from the coated samples.

3.3 Evaluation of polymer coating effect on coal permeability

The polymer coating serves to seal the interburden, but needs to be permeable on the coal layers so that gas and water can pass through from the reservoir into the well. This different behaviour arises from the way that water, which causes the phase inversion, contacts the polymer layer. For the coal layers the contact with water is at the coal/coating interface (in contrast with the interburden, where the contact is at the coating/fluid interface). To simulate the coal system, the coating is applied to the surface of a sample and water then induced to flow through the coal and then onto and through the coating. In contrast to polymer coating on interburden rock sample, after using same polymer coating procedure on coal samples, the water flow was applied through the coal sample and coating layer, Fig. 6.

Figure 14 presents a cross-sectional image of the polymer coating layer on the coal. Compared to the dense coating layer observed on the interburden rock (Fig. 9d), the polymer layer on coal shows finger-like macrovoids with interconnections extended through the whole layer. This connected pore structure results because the water from the core extracts NMP solvent from polymer/coal side towards polymer/water side. This spongy porous structure on the coal side is likely assisted by synthesis at relative high polymer concentrations and viscosity (Boussu et al. 2006). The permeability of the coal sample measured with 4% KCl brine before coating was (0.58 ± 0.12) mD, and after the PES coating was applied this permeability decreased to (0.3 ± 0.03) mD. Analysis of the potential impacts of this permeability decline on the CSG reservoir gas productivity are beyond the scope of this study, but we do acknowledge that such a decrease in coal permeability would likely have a large negative impact on the productivity of a coal seam. Therefore, while our results here highlight the potential of the PES polymer coating concept to reduce fines production and retain permeability across coal layers further work is required to both optimise the coating structure and develop downhole application methods.

4 Conclusions

A concept for minimising fines production in open hole completion CSG wells that arise from swelling, spalling and erosion of interburden layers using a well coating material is presented and examined in this paper. The coating is a polymer deposited by a phase inversion process mediated by water. By taking the advantage of permeability difference of interburden and coal, the polymer coating is induced to form the dense layer against the interburden (which blocks fines from being produced) but porous structure against the coal (which allows desirable gas and water flow into the well).

For interburden the fines generation in fresh water flow cell was significantly reduced by the coating. In experiments, the benefit was from about ~ 16 mL/m2 of fines released after an hour for uncoated interburden, to just ~ 2 mL/m2 of fines particles for the coated sample after 6 days. Long term immersion tests showed that the coating was effective in maintaining sample bulk integrity for the duration of the 30 day tests.

On the coal layers, the coating was permeable to gas and liquids, with only a small drop increase in the resistance to flow. With further development, the methodology provided in this study may provide a solution for mitigating solid production in coal seam gas wells.

References

Anderson R, Ratcliffe I, Greenwell H, Williams P, Cliffe S, Coveney P (2010) Clay swelling: a challenge in the oilfield. Earth Sci Rev 98:201–216

Bai T, Chen Z, Aminossadati SM, Pan Z, Liu J, Li L (2015) Characterization of coal fines generation: a micro-scale investigation. J Nat Gas Sci Eng 27 Part 2:862–875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2015.09.043

Baird J, Walz J (2006) The effects of added nanoparticles on aqueous kaolinite suspensions: I. Structural effects. J Colloid Interface Sci 297:161–169

Boussu K, Vandecasteele C, Van der Bruggen B (2006) Study of the characteristics and the performance of self-made nanoporous polyethersulfone membranes. Polymer 47:3464–3476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2006.03.048

Darley HC, Gray GR (1988) Composition and properties of drilling and completion fluids. Gulf Professional Publishing, Houston

Dzialowski A, Hale A, Mahajan S (1993) Lubricity and wear of shale: effects of drilling fluids and mechanical parameters. In: Paper presented at the SPE/IADC Drilling Conference, 22–25 February 1993

Fink J (2011) Petroleum engineer’s guide to oil field chemicals and fluids. Gulf Professional Publishing, Houston

Guan R, Zou H, Lu D, Gong C, Liu Y (2005) Polyethersulfone sulfonated by chlorosulfonic acid and its membrane characteristics. Eur Polym J 41:1554–1560

Hamilton SK, Esterle JS, Sliwa R (2014) Stratigraphic and depositional framework of the Walloon Subgroup, eastern Surat Basin, Queensland Australian. J Earth Sci 61:1061–1080. https://doi.org/10.1080/08120099.2014.960000

Hower WF (1977) Prevention and control of formation damage. In: Paper presented at the SPE Oklahoma City Regional Meeting, 1 Jan 1977

Jung Y, Son Y-H, Lee J-K, Phuoc TX, Soong Y, Chyu MK (2011) Rheological behavior of clay-nanoparticle hybrid-added bentonite suspensions: specific role of hybrid additives on the gelation of clay-based fluids. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 3:3515–3522

Khayet M, García-Payo MC (2009) X-ray diffraction study of polyethersulfone polymer, flat-sheet and hollow fibers prepared from the same under different gas-gaps. Desalination 245:494–500

Parker D, Bussink J, van de Grampel HT, Wheatley GW, Dorf E-U, Ostlinning E, Reinking K (2000) Polymers, high-temperature. In: Ullmann’s encyclopedia of industrial chemistry. Wiley, London. https://doi.org/10.1002/14356007.a21_449

Peng B, Luo P-Y, Guo W-Y, Yuan Q (2013) Structure–property relationship of polyetheramines as clay-swelling inhibitors in water-based drilling fluids. J Appl Polym Sci 129:1074–1079. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.38784

Pham H, Nguyen QP (2014) Effect of silica nanoparticles on clay swelling and aqueous stability of nanoparticle dispersions. J Nanopart Res 16:1–11

Schäfer AI, Fane AG, Waite TD (2005) Nanofiltration: principles and applications. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Schweizer PM, Kistler S (2012) Liquid film coating: scientific principles and their technological implications. Springer, Berlin

Shaw DB, Weaver CE (1965) The mineralogical composition of shales. J Sediment Res 35:213

Strathmann H, Kock K (1977) The formation mechanism of phase inversion membranes. Desalination 21:241–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0011-9164(00)88244-2

Towler B et al (2016) An overview of the coal seam gas developments in Queensland. J Nat Gas Sci Eng 31:249–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2016.02.040

Velde B (1992) Introduction to clay minerals. Chapman Hall, London

Yao Z, Cao D, Wei Y, Li X, Wang X, Zhang X (2016) Experimental analysis on the effect of tectonically deformed coal types on fines generation characteristics. J Petrol Sci Eng 146:350–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2016.05.041

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by industry funding provided via The University of Queensland Centre for Coal Seam Gas (www.ccsg.uq.edu.au). We thank also for their technical input to discussions Stephen Pell, Angela Roff and Alex Wood of Santos, and Jeanette Schouten and Ian Troth of QGC. The facilities and technical assistance of the Australian Microscopy & Microanalysis Research facility at the Centre for Microscopy & Microanalysis at The University of Queensland are acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ge, L., Hamilton, C., Febrina, R.T. et al. A phase inversion polymer coating to prevent swelling and spalling of clay fines in coal seam gas wells. Int J Coal Sci Technol 5, 179–190 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-018-0199-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-018-0199-0