Abstract

Background

Pleomorphic invasive lobular cancer (pleomorphic ILC) is a rare variant of ILC that is characterized by a classic ILC-like growth pattern combined with an infiltrative ductal cancer (IDC)-like high nuclear atypicality. There is an ongoing discussion whether pleomorphic ILC is a dedifferentiated form of ILC or in origin an IDC with a secondary loss of cohesion. Since gene promoter hypermethylation is an early event in breast carcinogenesis and thus may provide information on tumor progression, we set out to compare the methylation patterns of pleomorphic ILC, classic ILC and IDC. In addition, we aimed at analyzing the methylation status of pleomorphic ILC.

Methods

We performed promoter methylation profiling of 24 established and putative tumor suppressor genes by methylation-specific multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MS-MLPA) analysis in 20 classical ILC, 16 pleomorphic ILC and 20 IDC cases.

Results

We found that pleomorphic ILC showed relatively low TP73 and MLH1 methylation levels and relatively high RASSF1A methylation levels compared to classic ILC. Compared to IDC, pleomorphic ILC showed relatively low MLH1 and BRCA1 methylation levels. Hierarchical cluster analysis revealed a similar methylation pattern for pleomorphic ILC and IDC, while the methylation pattern of classic ILC was different.

Conclusion

This is the first report to identify TP73, RASSF1A, MLH1 and BRCA1 as possible biomarkers to distinguish pleomorphic ILC from classic ILC and IDC.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Invasive lobular breast cancer (ILC) is the second most prevalent histological breast cancer type that accounts for 10–15 % of all breast cancers [1, 2]. ILC differs from invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) in biology, histology, clinical presentation and response to therapy (reviewed in [3]). In contrast to ductal tumors, most lobular tumors show loss of E-cadherin expression, which often results from inactivating gene mutation and subsequent loss of heterozygosity or promoter hypermethylation [4]. Indeed, conditional knock-out mouse models have shown that somatic inactivation of E-cadherin leads to ILC development and progression [5, 6]. Among the eight different ILC variants described, classic ILC and pleomorphic ILC are the most common ones [3, 7]. Although the exact frequency of these ILC subtypes has not extensively been documented, approximately 60 % of all ILC cases is classic and approximately 13 % is pleomorphic (reviewed in [3]). Phenotypically, classic ILC is composed of small regular low grade and dissociated cells with intra-cytoplasmic vacuoles and small nuclei that exhibit a highly trabecular infiltrative growth pattern, often distributed in targetoid patterns around uninvolved ducts [8]. Pleomorphic ILC shows a similar growth and invasion pattern, but is composed of high grade polygonal cells with eccentric and highly pleomorphic nuclei. Furthermore, pleomorphic ILC tumors have been reported to be significantly larger than classic ILC tumors, and pleomorphic ILC patients often present with lymph node involvement and a higher rate of metastatic disease compared to classical ILC [9]. Moreover, the overall survival and recurrence rates of pleomorphic ILC patients are worse compared to classic ILC patients [10], indicating that pleomorphic ILC is a more aggressive form of breast cancer than classic ILC.

At the molecular level, classic and pleomorphic ILCs show similarities and differences. Both variants lack expression of basal markers like cytokeratin (CK)5 and CK14, but expresses the luminal epithelial markers CK8 and CK18 [11, 12]. ILCs are usually ‘luminal’ type breast cancers that express the estrogen receptor (ER) gene and genes involved in ER activation, including the progesterone receptor (PR) gene [13, 14]. Cytosolic translocation of p120-catenin due to inactivation of E-cadherin is a hallmark of ILC, whereas classic and pleomorphic ILCs do not over-express the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene [1, 15, 16]. While most classic ILCs lack expression of HER2 (ERBB2) [1], up to 81 % of pleomorphic ILCs express HER2 [17]. Moreover, although the somatic TP53 mutation frequency in pleomorphic ILC may be as high as 46 %, this is a rare event in classic ILC (approximately 6 %), suggesting a role for p53 loss in the etiology of pleomorphic ILC [17–19]. These findings are supported by observations in mammary-specific E-cadherin and p53 knock-out mice that develop a mouse variant of pleomorphic ILC [6]. Furthermore, in contrast to classic ILC, pleomorphic ILC often expresses the apocrine differentiation marker gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 (GCDFP15) and the androgen receptor (AR) [17, 20]. The origin of pleomorphic ILC tumors is still under debate and, since results from conditional mouse models have suggested that all lobular cancer types are evolutionary linked (reviewed in [21]), It is currently unclear whether pleomorphic ILC is a dedifferentiated form of classic ILC or whether it evolves from ductal type tumors. The differential diagnosis between these breast cancer subtypes is important because surgery planning of ILC requires pre-operative MRI, due to an often more diffuse and multifocal growth pattern of lobular tumors and a higher incidence of contralateral tumors [22].

In cancer, DNA methylation is often disturbed and can act as a driving force during tumor progression [23, 24] (reviewed in [25]). DNA methylation occurs by the enzymatic transfer of a methyl group onto the carbon-5 position of a cytosine (often part of a cytosine phosphate guanosine (CpG) dinucleotide), which can result in gene silencing [26]. Promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes is considered to be an early event in carcinogenesis since high methylation levels have been found in columnar cell lesions, the earliest recognized breast cancer precursors [27]. Hence, methylation patterns may give insight in tumor progression and, thus, shed light on the precursor origin of pleomorphic ILC tumors. In light of the possible future extrapolation to methylation detection in biopsy, blood, nipple fluid and urine samples, DNA hypermethylation is a promising area in the clinical biomarker field. DNA hypermethylation analyses can be performed on formalin-fixed tissues and, thus, are suited for molecular profiling and the identification of markers that predict therapeutic responsiveness.

Here we have identified promoter methylation patterns in pleomorphic ILC in relation to ILC and IDC to identify pleomorphic ILC biomarkers. Methylation was assessed by methylation-specific multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MS-MLPA), a highly reproducible technique that only requires small amounts (10 ng) of short DNA fragments and that shows high concordance with other established techniques such as quantitative multiplex methylation-specific PCR [28, 29]. MS-MLPA can be used in samples with mixed populations of cells. As long as 30 % of methylated DNA/tumor DNA is present in the sample, the methylation status will be recognized correctly [30]. We assessed the promoter methylation status of 24 tumor suppressor genes and compared 16 pleomorphic ILC, 20 classic ILC and 20 IDC cases. We found that the methylation patterns of classic ILC and IDC were comparable, and that the classic ILC and IDC profiles were mildly different from pleomorphic ILC. Furthermore, we found that the methylation status of the RASSF1A, TP73, MLH1 and BRCA1 gene promoters can be used as stratification markers to distinguish pleomorphic ILC from classic ILC and IDC.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Patient material

Patient samples were derived from the archives of the Departments of Pathology at the University Medical Centre Utrecht, the Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, the Institute of Pathology, Paderborn, Germany, and the Department of Pathology, Bács-Kiskun County Teaching Hospital, Kecskemét, Hungary. The clinicopathological characteristics of the patient samples are provided in Table 1. Classic and pleomorphic ILC and IDC cases were selected based on examination of haematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained slides by at least two pathologists. The use of left-over material was approved by the Tissue Science Committee of the UMC Utrecht [31]. Histological grades were assessed according to the Nottingham modification of the Scarff-Bloom-Richardson grading system [32]. ER and PR were considered positive when ≥10 % of the cells showed positive nuclear staining. HER2 was scored according to the modified DAKO scoring system, where only a score of 3+ was considered positive. The mitotic activity index (MAI) was assessed as reported before [33].

2.2 Methylation-specific multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification

H&E stained sections were used to reveal pre-invasive lesions, necrosis and admixed lymphocytic infiltrates and to guide micro-dissections for DNA extraction. Areas with necrosis, dense lymphocytic infiltrates and pre-invasive lesions were intentionally avoided. All areas selected for micro-dissection had a tumor percentage of at least 70 %. Tumor tissue was derived from 4 μm thick sections (5 to 10, formalin-fixed paraffin embedded) and DNA was isolated by overnight incubation in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0; 0.5 % Tween 20) with proteinase K (10 mg/ml, Roche) at 56 °C, followed by boiling for 10 min. After a 5 min centrifugation step (12,000 g), 5 μl supernatant was used for MLPA analysis according to the manufacturer’s instructions, using the ME001-C2 methylation kit (MRC-Holland). The principle of MS-MLPA has been described elsewhere [28] and the PCR and data analysis procedures were performed as reported before [27]. The ME001-C2 MS-MLPA probe mix contains 26 probes, detecting the methylation status of promoter CpG sites of 24 established and putative tumor suppressor genes (Table 2) that are frequently silenced by hypermethylation in tumors, but not in blood-derived DNA of healthy individuals. In addition, we included 15 reference probes. The cumulative methylation index (CMI) was calculated as the sum of the methylation percentage of all genes, as described before [34].

2.3 Statistics

Statistic calculations and ROC curve analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistics v20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Two-sided p < 0.05 was considered significant. Absolute methylation levels were used to calculate p-values upon comparing classic ILC, pleomorphic ILC and IDC samples, using the Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U Test, and the Kruskal-Wallis test. Through Bonferroni-Holm correction of all p-values we excluded false-positives caused by multiple comparisons. Logistic regression analysis was used to reveal the best (combination of) genes able to discriminate pleomorphic ILC from classic ILC and/or IDC. A backward stepwise method was used until the most predictive variables remained. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering (Euclidean metric) using the statistical program R was performed on Z-scores to identify relevant clusters.

3 Results and discussion

Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA analysis was carried out to assess differential methylation patterns in our non-parametric methylation data of the three breast cancer subtypes, i.e., classic ILC, pleomorphic ILC and IDC (Fig. 1; patient samples listed in Table 1). Sixteen of the 24 genes tested (listed in Table 2), including BRCA1, showed significant differences between the groups. However, after correction for multiple comparisons only the methylation patterns of TP73 (p < 0.002), MLH1_b (p < 0.002) and RASSF1A_x (p < 0.002) were found to be significantly different between the three breast cancer subtypes (Fig. 2).

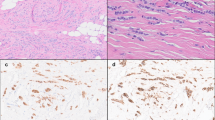

Representative H&E images of classic and pleomorphic ILC and IDC. Classic ILC is characterized by small regular cells, small nuclei and a low mitotic rate (a). The formation of single (‘indian’) files is a common characteristic of classic ILC (enlarged in right image). Pleomorphic ILCs display polygonal cells and frequent mitoses (b). The nuclei are often eccentric, highly pleomorphic and show distinctive nucleoli (enlarged in right image, arrows). IDC tumors are not characterized by specific features like ILC (c). In contrast to ILC, IDC often shows formation of ducts within the tumor (left and right image). All size bars indicate 25 μm

Methylation differences between classic and pleomorphic ILC. Scatter dot plots of the absolute methylation values that were found to be significantly different between the three breast cancer types. TP73, MLH1_y and RASSF1A_x were significantly different between pleomorphic and classic ILC, while only MLH1_y and BRCA1 were significantly different between pleomorphic ILC and IDC. All p-values are derived from the Mann–Whitney analysis. The horizontal bars represent the median

A (post hoc) Mann–Whitney test followed by multiple comparisons correction was carried out, using the 16 genes derived from the above Kruskal-Wallis analysis, to specify the differences between classic and pleomorphic ILCs. By doing so, we found that the methylation patterns of TP73, MLH1_y and RASSF1A_x were significantly different between the classic and pleomorphic ILCs. When compared to classic ILCs, pleomorphic ILCs showed less promoter methylation of the MLH1_y (p = 0.003) and TP73 (p = 0.001) genes (Fig. 2), while the promoter methylation of the RASSF1A gene was found to be higher in pleomorphic ILCs (p = 0.001). The CMI of the pleomorphic ILCs was not significantly different from that of classic ILCs (353.3 versus 390.0, respectively; p = 0.437). In logistic regression analyses TP73 (p = 0.017) and RASSF1A (p = 0.005) showed a joint independent discriminative value for pleomorphic ILCs versus classic ILCs (area under the curve (AUC) 0.888, CI 0.764-1.000, p < 0.001), with a combined receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve-based sensitivity and specificity of 81 and 100 %, respectively.

After correction for multiple comparisons, we found that the methylation levels of both MLH1_y (p = 0.001) and BRCA1 (p = 0.002) were significantly lower in pleomorphic ILCs than in IDCs (Fig. 2). The mean CMI of pleomorphic ILCs was not significantly different from that of IDCs (353.3 vs. 392.6, respectively; p = 0.357), indicating that the overall methylation patterns of these two breast cancer subgroups were similar. Logistic regression analysis showed that only BRCA1 methylation (p = 0.002) had an independent discriminative value for pleomorphic ILC versus IDC (area under the curve (AUC) 781, CI 0.623-0.939, p = 0.004), with a ROC curve-based sensitivity and specificity of 75 and 81 %, respectively.

In order to determine if the absolute MS-MLPA values of our samples clearly defined our three breast cancer subtypes, we performed hierarchical Euclidean cluster analysis on all genes tested (Fig. 3a) and on the four genes that showed significant differences in the Mann–Whitney tests (Fig. 3b). Both cluster analyses revealed some clustering of pleomorphic ILC samples with IDC samples, while classic ILC samples usually formed separate clusters with other IDC samples.

Cluster analysis of the breast cancer methylation data. (a) Hierarchical cluster analysis of Z-scores based on absolute methylation values by MS-MLPA of all interrogated genes in classic ILC (light grey), pleomorphic ILC (red) and IDC (black). (b) Hierarchical cluster analysis of Z-scores based on absolute methylation values of the four significantly differentially methylated genes according to the Mann–Whitney analysis

The different advantages and possibilities of DNA methylation analyses for disease stratification and prognostication have led to a large amount of reports in the literature, also on breast cancer. However, the vast majority of these reports has so far focused on IDC, and we are unaware of any report on DNA methylation in pleomorphic ILC. Interestingly, in two reports the DNA methylation patterns were compared in ILC and IDC, and it was found that they were very similar in these two breast cancer subtypes [35, 36]. Our results are in agreement with this notion, while pleomorphic ILC appeared to exhibit a distinct methylation pattern with a CMI similar to that of classic ILC and IDC.

BRCA1, MLH1 and RASSF1A are established tumor suppressor genes and TP73 is a putative tumor suppressor gene. BRCA1 and MLH1 are involved in DNA repair and their functional loss causes an accumulation of gene defects. Interestingly, we found a significant association between the presence of MLH1_x (p = 0.013) and BRCA1 (p = 0.013) promoter methylation and a high MAI (>12), and between MLH1_x and BRCA1 promoter methylation (p = 0.004) (data not shown). Previously, BRCA1 promoter methylation has been observed in 10–15 % of all sporadic breast cancer patients [37, 38]. Only 4–5 % of the lobular breast tumors carry a deleterious BRCA1 mutation [39], and none of the 11 previously analyzed ILC samples showed BRCA1 hypermethylation [37]. As we found that the MLH1 and BRCA1 methylation levels were lower in pleomorphic ILC compared to IDC, they may not be suitable as therapeutic targets, but they may be used as biomarkers.

To test the reproducibility of MS-MLPA, we have previously taken along 10 primary breast tumor samples in duplicate in at least 8 separate MS-MLPA runs (unpublished data). By doing so, we found that the TP73, MLH1_y, RASSF1A_x and BRCA1 probes have an average standard deviation of 0.01, 0.01, 0.05 and 0.02 per sample, respectively. Based on these findings, we anticipate that the between-group differences observed for TP73 and RASSF1A_x are reproducible and reliable. The differences between groups observed for MLH1_y and BRCA1 are, however, less pronounced and may be the result of technical variability. We, therefore, recommend validating these findings by an independent highly sensitive and quantitative technique.

TP73 is subject to alternative splicing, and the use of an alternative promoter results in different p73 isoforms that exhibit contrasting effects on tumor development [40]. Although TP73 promoter methylation has been correlated with a poor survival of breast cancer patients [41], this methylation also impairs binding of the transcriptional repressor ZEB1, which may result in an increase in TP73 expression [42]. Unfortunately, studies reporting TP73 methylation levels in normal breast tissue are scarce and not combined with protein or RNA expression analyses [27, 43], and TP73 methylation studies in ILC have not been reported yet. As we found TP73 promoter methylation to be relatively low in pleomorphic ILC compared to classic ILC, it may serve as a biomarker, whereas it is considered less suited as a target for therapy. Further studies are needed to determine the effect of TP73 methylation on protein expression and to determine the functional consequences in pleomorphic ILC.

RASSF1A promoter methylation was found to be higher in pleomorphic ILC than in classic ILC. Although uncommon, RASSF1A polymorphisms and deletions have been encountered and RASSF1A promoter hypermethylation has been found to frequently occur in different tumor types [44]. About 70–85 % of ILC and IDC cases show RASSF1A hypermethylation [35, 45]. Also, hypermethylation of RASSF1A in pre-operative serum of breast cancer patients has been found to serve as an independent prognostic marker correlated with a poor overall survival [46]. Since RASSF1A hypermethylation is rarely observed in normal breast tissues, it is considered to be an early event in breast cancer development [46, 47] and, as such, it may serve as a promising breast cancer biomarker. RASSF1 is a member of the RASSF family of genes (RASSF 1–8), and gives rise to 8 different isoforms due to alternative splicing and alternative promoter usage [48]. Next to the RASSF proteins, RAF and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) are also known as RAS effectors, i.e., proteins that specifically bind the GTP-bound form of RAS. In contrast to RAF and PI3K, which control proliferation and survival, the RASSF genes are known to act as tumor suppressors [48]. RASSF1A null-mice show an increased incidence of spontaneous tumor formation, a decreased survival rate and an increased susceptibility for mutagens (reviewed in [48]). In addition, it has been found that exogenous expressions of RASSF1A in different tumor cell lines reduces their viability, proliferation and invasion [48]. These findings, combined with our data showing increased RASSF1A promoter methylation in pleomorphic ILC, renders RASSF1A into an interesting and functional biomarker for lobular breast cancer.

In conclusion, our data indicate that the promoter methylation signature of the TP73, MLH1, RASSF1A and BRCA1 genes may serve as a biomarker to distinguish pleomorphic ILC from classic ILC and IDC. Since pleomorphic ILC is considered to be an aggressive breast cancer variant, and since pre-operative MRI is favorable for ILC patients but not for IDC patients, pleomorphic ILC biomarkers may be useful for treatment design in cases where a pathological distinction between ILC and IDC is questionable. Future research is needed to confirm our findings in an independent patient group and to evaluate the potential of the respective methylation markers as therapeutic targets.

References

G. Arpino, V.J. Bardou, G.M. Clark, R.M. Elledge, Infiltrating lobular carcinoma of the breast: tumor characteristics and clinical outcome. Breast Cancer Res. 6, R149 (2004)

E. Gudlaugsson, I. Skaland, E.A.M. Janssen, P.J. Van Diest, F.J. Voorhorst, K. Kjellevold, A.z. Hausen, J.P.A. Baak, Prospective multicenter comparison of proliferation and other prognostic factors in lymph node negative lobular invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 121, 35–40 (2010)

E. Vlug, C. Ercan, E. Wall, P. J. Diest, P. W. B. Derksen, Lobular Breast Cancer: Pathology, Biology, and Options for Clinical Intervention Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 1–15 (2013)

G. Berx, A.M. Cleton-Jansen, K. Strumane, W.J. de Leeuw, F. Nollet, F. Van Roy, C. Cornelisse, E-cadherin is inactivated in a majority of invasive human lobular breast cancers by truncation mutations throughout its extracellular domain. Oncogene 13, 1919–1925 (1996)

P.W.B. Derksen, X. Liu, F. Saridin, H. Van Der Gulden, J. Zevenhoven, B. Evers, J.R. van Beijnum, A.W. Griffioen, J. Vink, P. Krimpenfort, J.L. Peterse, R.D. Cardiff, A. Berns, J. Jonkers, Somatic inactivation of E-cadherin and p53 in mice leads to metastatic lobular mammary carcinoma through induction of anoikis resistance and angiogenesis. Cancer Cell 10, 437–449 (2006)

P.W.B. Derksen, T.M. Braumuller, E. Van Der Burg, M. Hornsveld, E. Mesman, J. Wesseling, P. Krimpenfort, J. Jonkers, Mammary-specific inactivation of E-cadherin and p53 impairs functional gland development and leads to pleomorphic invasive lobular carcinoma in mice. Disease Models Mech. 4, 347–358 (2011)

N. Weidner, J.P. Semple, Pleomorphic variant of invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast. Hum. Pathol. 23, 1167–1171 (1992)

Z. Varga, E. Mallon, Histology and immunophenotype of invasive lobular breast cancer. daily practice and pitfalls. Breast Dis. 30, 15–19 (2008)

C.L. Buchanan, L.W. Flynn, M.P. Murray, F. Darvishian, M.L. Cranor, J.V. Fey, T.A. King, L.K. Tan, L.M. Sclafani, Is pleomorphic lobular carcinoma really a distinct clinical entity? J. Surg. Oncol. 98, 314–317 (2008)

L. Monhollen, C. Morrison, F.O. Ademuyiwa, R. Chandrasekhar, T. Khoury, Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma: a distinctive clinical and molecular breast cancer type. Histopathology 61, 365–377 (2012)

O. Fadare, S.A. Wang, D. Hileeto, The expression of cytokeratin 5/6 in invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast: evidence of a basal-like subset. Hum. Pathol. 39, 331–336 (2008)

M.-M. Shao, S.K. Chan, A.M.C. Yu, C.C.F. Lam, J.Y.S. Tsang, P.C.W. Lui, B.K.B. Law, P.-H. Tan, G.M. Tse, Keratin expression in breast cancers. Virchows Arch. 461, 313–322 (2012)

C. Perou, T. Sorlie, M. Eisen, M. van de Rijn, S. Jeffrey, C. Rees, J. Pollack, D. Ross, H. Johnsen, L. Akslen, O. Fluge, A. Pergamenschikov, C. Williams, S. Zhu, P. Lonning, A. Borresen-Dale, P. Brown, D. Botstein, Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 406, 747–752 (2000)

C. Sotiriou, S.-Y. Neo, L.M. McShane, E.L. Korn, P.M. Long, A. Jazaeri, P. Martiat, S.B. Fox, A.L. Harris, E.T. Liu, Breast cancer classification and prognosis based on gene expression profiles from a population-based study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 10393–10398 (2003)

J.S. Reis-Filho, P.T. Simpson, C. Jones, D. Steele, A. Mackay, M. Iravani, K. Fenwick, H. Valgeirsson, M. Lambros, A. Ashworth, J. Palacios, F. Schmitt, S.R. Lakhani, Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma of the breast: role of comprehensive molecular pathology in characterization of an entity. J. Pathol. 207, 1–15 (2005)

D. Sarrió, B. Pérez-Mies, D. Hardisson, G. Moreno-Bueno, A. Suárez, A. Cano, J. Martín-Pérez, C. Gamallo, J. Palacios, Cytoplasmic localization of p120ctn and E-cadherin loss characterize lobular breast carcinoma from preinvasive to metastatic lesions. Oncogene 23, 3272–3283 (2004)

L. Middleton, D. Palacios, B. Bryant, P. Krebs, C. Otis, M. Merino, Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma: morphology, immunohistochemistry, and molecular analysis. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 24, 1650–1656 (2000)

P.T. Simpson, J.S. Reis-Filho, M.B.K. Lambros, C. Jones, D. Steele, A. Mackay, M. Iravani, K. Fenwick, T. Dexter, A. Jones, L. Reid, L. Da Silva, S.J. Shin, D. Hardisson, A. Ashworth, F.C. Schmitt, J. Palacios, S.R. Lakhani, Molecular profiling pleomorphic lobular carcinomas of the breast: evidence for a common molecular genetic pathway with classic lobular carcinomas. J. Pathol. 215, 231–244 (2008)

C. Ercan, P.J. Van Diest, B. van der Ende, J. Hinrichs, P. Bult, H. Buerger, E. van der Wall, P.W.B. Derksen, p53 mutations in classic and pleomorphic invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast. Cell. Oncol. 35, 111–118 (2012)

V. Eusebi, F. Magalhaes, J.G. Azzopardi, Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma of the breast: an aggressive tumor showing apocrine differentiation. Hum. Pathol. 23, 655–662 (1992)

M. Christgen, P.W. Derksen, Lobular breast cancer: molecular basis, mouse and cellular models. Breast Cancer Res. 17, 491 (2015)

F. Sardanelli, G.M. Giuseppetti, P. Panizza, M. Bazzocchi, A. Fausto, G. Simonetti, V. Lattanzio, A. Del Maschio, Italian trial for breast MR in multifocal/multicentric cancer, sensitivity of MRI versus mammography for detecting foci of multifocal, multicentric breast cancer in Fatty and dense breasts using the whole-breast pathologic examination as a gold standard. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 183, 1149–1157 (2004)

A. Rawat, G. Gopisetty, R. Thangarajan, E4BP4 is a repressor of epigenetically regulated SOSTDC1 expression in breast cancer cells. Cell. Oncol. 37, 409–419 (2014)

J.S. de Groot, X. Pan, J. Meeldijk, E. van der Wall, P.J. Van Diest, C.B. Moelans, Validation of DNA promoter hypermethylation biomarkers in breast cancer--a short report. Cell. Oncol. 37, 297–303 (2014)

P.A. Jones, S.B. Baylin, The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 415–428 (2002)

J. Jovanovic, J.A. Rønneberg, J. Tost, V. Kristensen, The epigenetics of breast cancer. Mol. Oncol. 4, 242–254 (2010)

A.H.J. Verschuur-Maes, P.C. de Bruin, P.J. Van Diest, Epigenetic progression of columnar cell lesions of the breast to invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 136, 705–715 (2012)

A.O.H. Nygren, N. Ameziane, H.M.B. Duarte, R.N.C.P. Vijzelaar, Q. Waisfisz, C.J. Hess, J.P. Schouten, A. Errami, Methylation-specific MLPA (MS-MLPA): simultaneous detection of CpG methylation and copy number changes of up to 40 sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, e128 (2005)

K.P.M. Suijkerbuijk, X. Pan, E. van der Wall, P.J. Van Diest, M. Vooijs, Comparison of different promoter methylation assays in breast cancer. Anal. Cell. Pathol. 33, 133–141 (2010)

C. Hömig-Hölzel, S. Savola, Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) in tumor diagnostics and prognostics. Diagn. Mol. Pathol. 21, 189–206 (2012)

P.J. Van Diest, No consent should be needed for using leftover body material for scientific purposes. BMJ 325, 648–651 (2002)

C.W. Elston, I.O. Ellis, Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer. I. The value of histological grade in breast cancer: experience from a large study with long-term follow-up. Histopathology 19, 403–410 (1991)

P.J. van Diest, J.P. Baak, P. Matze-Cok, E.C. Wisse-Brekelmans, C.M. van Galen, P.H. Kurver, S.M. Bellot, J. Fijnheer, L.H. van Gorp, W.S. Kwee, Reproducibility of mitosis counting in 2,469 breast cancer specimens: results from the multicenter morphometric mammary carcinoma project. Hum. Pathol. 23, 603 (1992)

K.P.M. Suijkerbuijk, M.J. Fackler, S. Sukumar, C.H. van Gils, T. van Laar, E. van der Wall, M. Vooijs, P.J. van Diest, Methylation is less abundant in BRCA1-associated compared with sporadic breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 19, 1870–1874 (2008)

M.J. Fackler, M. McVeigh, E. Evron, E. Garrett, J. Mehrotra, K. Polyak, S. Sukumar, P. Argani, DNA methylation of RASSF1A, HIN-1, RAR-beta, Cyclin D2 and Twist in in situ and invasive lobular breast carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 107, 970–975 (2003)

Y.K. Bae, A. Brown, E. Garrett, D. Bornman, M.J. Fackler, S. Sukumar, J.G. Herman, E. Gabrielson, Hypermethylation in histologically distinct classes of breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 5998–6005 (2004)

M. Esteller, J.M. Silva, G. Dominguez, F. Bonilla, X. Matias-Guiu, E. Lerma, E. Bussaglia, J. Prat, I.C. Harkes, E.A. Repasky, E. Gabrielson, M. Schutte, S.B. Baylin, J.G. Herman, Promoter hypermethylation and BRCA1 inactivation in sporadic breast and ovarian tumors. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 92, 564–569 (2000)

V. Birgisdottir, O.A. Stefansson, S.K. Bodvarsdottir, H. Hilmarsdottir, J.G. Jonasson, J.E. Eyfjord, Epigenetic silencing and deletion of the BRCA1 gene in sporadic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 8, R38 (2006)

C. Adem, C. Reynolds, C.L. Soderberg, J.M. Slezak, S.K. McDonnell, T.J. Sebo, D.J. Schaid, J.L. Myers, T.A. Sellers, L.C. Hartmann, R.B. Jenkins, Pathologic characteristics of breast parenchyma in patients with hereditary breast carcinoma, including BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Cancer 97, 1–11 (2003)

V. Dötsch, F. Bernassola, D. Coutandin, E. Candi, G. Melino, p63 and p73, the ancestors of p53. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2, a004887 (2010)

D.M. Marzese, D.S.B. Hoon, K.K. Chong, F.E. Gago, J.I. Orozco, O.M. Tello, L.M. Vargas-Roig, M. Roqué, DNA methylation index and methylation profile of invasive ductal breast tumors. J. Mol. Diagn. 14, 613–622 (2012)

G. Fontemaggi, A. Gurtner, S. Strano, Y. Higashi, A. Sacchi, G. Piaggio, G. Blandino, The transcriptional repressor ZEB regulates p73 expression at the crossroad between proliferation and differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 8461–8470 (2001)

K.M. Chen, J.K. Stephen, U. Raju, M.J. Worsham, Delineating an epigenetic continuum for initiation, transformation and progression to breast cancer. Cancers (Basel) 3, 1580–1592 (2011)

R. Dammann, U. Schagdarsurengin, C. Seidel, M. Strunnikova, M. Rastetter, K. Baier, G.P. Pfeifer, The tumor suppressor RASSF1A in human carcinogenesis: an update. Histol. Histopathol. 20, 645 (2005)

K. Sebova, I. Zmetakova, V. Bella, K. Kajo, I. Stankovicova, V. Kajabova, T. Krivulcik, Z. Lasabova, M. Tomka, S. Galbavy, I. Fridrichova, RASSF1A and CDH1 hypermethylation as potential epimarkers in breast cancer. Cancer Biomark. 10, 13–26 (2011)

H.M. Müller, A. Widschwendter, H. Fiegl, L. Ivarsson, G. Goebel, E. Perkmann, C. Marth, M. Widschwendter, DNA methylation in serum of breast cancer patients: an independent prognostic marker. Cancer Res. 63, 7641–7645 (2003)

U. Lehmann, F. Länger, H. Feist, S. Glöckner, B. Hasemeier, H. Kreipe, Quantitative assessment of promoter hypermethylation during breast cancer development. Am. J. Pathol. 160, 605–612 (2002)

L. van der Weyden, D.J. Adams, The Ras-association domain family (RASSF) members and their role in human tumourigenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1776, 58–85 (2007)

Acknowledgments

We thank Petra van der Groep and Nathalie ter Hoeve for excellent assistance with immunohistochemistry. We thank Stefan M. Willems for pathological diagnoses. All members of the Derksen and Van Diest laboratories are acknowledged for support and discussions.

Author contributions

The experiments were conceived and designed by CBM, EJV, PJD and PWBD. EJV performed the experiments. EJV, CE and PJD performed the pathological analyses and scoring of human tumor samples. EJV and CBM analyzed the methylation data. EJV, CBM, PJD and PWBD wrote the paper.

Disclosure

This work was supported by a grant from The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO-VIDI 917.96.318). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Moelans, C.B., Vlug, E.J., Ercan, C. et al. Methylation biomarkers for pleomorphic lobular breast cancer - a short report. Cell Oncol. 38, 397–405 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13402-015-0241-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13402-015-0241-9