Abstract

Tribulus terrestris L., commonly called puncture vine and gokhru, is an important member of Zygophyllaceae. The species is highly important in context to therapeutic uses and provides important active principles responsible for treatment of various diseases and also used as tonic. It is widely distributed in tropical regions of India and the world. However, status of its genetic diversity remained concealed due to lack of research work in this species. In present study, genetic diversity and structure of different populations of T. terrestris from north India was examined at molecular level using newly developed Simple Sequence Repeat (SSR) markers. In total, 20 primers produced 48 alleles in a size range of 100–500 bp with maximum (4) fragments amplified by TTMS-1, TTMS-25 and TTMS-33. Mean Polymorphism Information Content (PIC) and Marker Index (MI) were 0.368 and 1.01, respectively. Dendrogram showed three groups, one of which was purely containing accessions from Rajasthan while other two groups corresponded to Punjab and Haryana regions with intermixing of few other accessions. Analysis of molecular variance partitioned 76 % genetic variance within populations and 24 % among populations. Bayesian model based STRUCTURE analysis detected two genetic stocks for analyzed germplasm and also detected some admixed individuals. Different geographical populations of this species showed high level of genetic diversity. Results of present study can be useful in identifying diverse accessions and management of this plant resource. Moreover, the novel SSR markers developed can be utilized for various genetic analyses in this species in future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

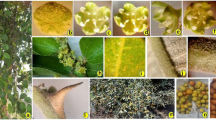

Tribulus terrestris commonly known as puncture vine and Gokhru, belonging to family Zygophyllaceae, is an annual herbaceous plant. The plant is native to the South and East Europe and West Asia. It is widely distributed in the warm regions of Asia, Africa, Europe, America and Australia (Topia et al. 1994; Abeywickrama and Bean 1991; Kostova et al. 2002). The species is commonly distributed throughout tropical and warmer regions of India. It occurs naturally in many Indian states with warm climate and reported from eastern, western, northern, southern and central parts of country (Mishra and Bisht 2012; Das and Ghosh 2014; Fatima et al. 2014; Pandey 2014, 2015). It is a prostrate to procumbent annual, hairy herb. Leaves are pinnately compound, leaflets are 4–8 paired, subsessile, ovate or elliptic. Flowers are yellowish colored, mericarps not winged but distinctly spinous (Fig. 1). The fruits of the species are very distinguished in nature like a stellate and are known as ‘Chih-hsing’ in China and ‘Goat head’ in USA. It is used as traditional ayurvedic medicine in various health disorders. It contains saponins, steroids, estradiol, flavonoids, alkaloids, unsaturated fatty acids, vitamins, tannins, resins, nitrate potassium, aspartic acid and glutamic acid (Gauthaman and Adaikan 2005). The plant is a rich source of saponins, of which protodioscin has received a large attention in regards to sexual dysfunction issues (Adimoelja 2000). Now-a-days, full plant or its fruits are used in large number of purposes as skin-care, human hormone regulation, antibacterial, anti-inflammation, antivirus and immunostimulant. The whole plant is useful in strangury, dyspepsia, helminthiasis, cough, asthma, cardiopathy, skin diseases, hypertension and rheumatic arthritis (Sivarajan and Balachandran 1994; Warrier et al. 1996; Petkov 2011). Thus, it is well known that all parts of the plant have great medicinal potential. T. terrestris exhibits both, self- and cross-pollination mechanisms (Ganie 2011). This herb propagates through the seeds only. The species is dibasic depending on base number x = 6 and 10. Cytologically, the species is quite variable with intra-specific polyploids from diploid to octaploid (2n = 12, 24, 36, 48; Morrison and Scott 1996). From India, the chromosome count of 2n = 24, 32, 36, 48, 72, 96 has been reported by various workers. From Rajasthan, three cytotypes of the species, i.e., tetraploid, hexaploid and octaploid have been reported (Gupta et al. 2016). Morrison and Scott (1996) suggested that these various polpyploids are originated from allopolyploid complex. Propagation through seeds presents opportunity for analyzing polymorphisms of these populations which are not so far apart, as reproductive mode results in allelic recombinations. In northern parts of India, this species is widely found in Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan. As it requires very less water for its growth, it is commonly found in bare and uncultivated lands. Although, T. terrestris is cultivated in various regions of Rajasthan for its medicinal utilities but these practices further needs elite germplasm for sustainable utilization. On the other, due to preference to major cereal crops and other cash crops in Punjab and Haryana, populations of this species often uprooted in large scale which is posing a threat to genetic diversity of this species. Therefore, it becomes imperative to characterize its existing germplasm so that diverse germplasm can be identified and maintained for future.

To study genetic diversity and population structure at molecular level different types of DNA markers can be used. However, Simple Sequence Repeats (SSRs; Tautz 1989) and Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) markers are the most preferred markers now-a-days. These DNA markers are frequently applied for genetic diversity evaluation, population structure assessment, for inferring interrelationships and linkage mapping. SSR markers are multiallelic, evenly distributed in genome, cross-transferable in related species and genera, and are amenable to automation. SNP markers are mostly biallelic, had higher frequency in genome and exhibit high heritability (Gaur et al. 2012; Verma et al. 2015). SNP markers are less polymorphic than SSRs but their abundance in genome overcomes this limitation (Mammadov et al. 2012). As both these markers represent different genomic regions they can provide different views for a similar investigation (Singh et al. 2014). SNP markers require prior sequence information while the cross-transferable nature of SSR markers makes them more favorable and useful for genetic analysis in related species lacking sequence data. Furthermore, Mesak et al. (2014) by comparing these two markers for characterization of clonal lineages in fish suggested that SNP data sets demand more caution and stringency to achieve good results and to reduce false signals. Thus, SSR appears more favourable and accessible to conduct genetic analysis in non-modal plant species, as SNP requires sophisticated instrumentation for their validation. Therefore, in present study we utilized T. terrestris sequence data available at National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) for designing new SSR markers to evaluate the genetic diversity and population structure of this species in north India.

Materials and methods

Plant material and DNA extraction

In present study twenty-six T. terrestris accessions collected from different geographical locations of three north Indian states (Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan) were analyzed. Of these, twelve samples were from Punjab, six from Haryana and eight from Rajasthan. A detatiled account of all the accessions is given in Table 1. Young fresh leaves were collected from each sample for isolation of DNA. DNA was extracted following the CTAB method (Doyle and Doyle 1990). DNA stocks preparation in Tris (10 mM) EDTA (1 mM) buffer, quantification and dilutions for making working stocks was done according to Sharma et al. (2015).

Sequence data and primer designing

Sequence data at NCBI was searched for T. terrestris. A total of 637 nucleotide sequences were available as on 12th May 2015. These nucleotide sequences were retrieved and assembled using EGassembler (Masoudi-Nejad et al. 2006) to make final consensus sequences and to remove the redundancy. The resulted contigs and singletons were then searched for presence of SSRs with minimum repeat length of 10 bp using SSRIT (Temnykh et al. 2001). SSR primers were designed from suitable SSR containing sequences using PRIMER 3 software (Rozen and Skaletsky 2000) with default settings. These SSRs were named as- Tribulus terrestris MicroSatellite (TTMS).

SSR genotyping

PCR reactions were performed in a 10 µL reaction volume as per Sharma et al. (2009). PCR amplification was carried out in Biorad Thermal Cycler (Biorad, Australia) and all PCR reactions were performed at one cycle of 4 min at 94 °C as initial denaturation, followed by 35 cycles with a denaturation step at 94 °C for 30 s, an annealing step for 45 s at respective annealing temperature of each primer in a range of 51–55 °C (Table 2), and an extension step at 72 °C for 1 min, followed by last cycle of extension at 72 °C for 7 min. PCR products were resolved on 3 % agarose gel and size of each fragment was estimated using 50 bp ladder (MBI Fermentas, Lithuania). Gels were prepared and run in 1X TBE buffer and visualization of fragments was done using ethidium bromide. Permanent photographs of gels were taken in gel documentation system (Bio-Rad laboratories-segrate, Milan, Italy).

Data analysis

All SSR fragments were scored manually and converted into binary data, i.e., 1 for presence of band and 0 for absence of band. Polymorphism information content (PIC) was calculated using formula given by Roldán-Ruiz et al. (2000), i.e., PICi = 2fi (1 − fi). Where PICi is the polymorphic information content of marker i, fi is the frequency of the marker bands present and (1 − fi) is frequency of marker bands absent. Marker index (MI) was calculated by applying the formula given by Prevost and Wilkinson (1999). Distance-based cluster analysis was performed and dendrogram based on the unweighted pair group method of arithmetic mean (UPGMA) was constructed using Jaccard’s similarity coefficient with the help of DARwin (Perrier and Jacquemoud-Collet 2006). Bayesian clustering methods are powerful computational tools meant for estimation of various features of population. STRUCTURE, which is a Bayesian clustering software assigns the individuals to different populations and hybrid zones on the basis of allele frequencies of genotypes. The method assumes K (unknown) populations for the given data set and the value of K can be estimated by posterior probability of the data for a given K, Pr (X|K) as per Pritchard et al. (2000). STRUCTURE software, version: 2.3.3 (Pritchard et al. 2000; Falush et al. 2007) was used to assess the genetic structure at population level as well as to detect genetic stocks contributing to this germplasm collection. Ancestry model with admixture and correlated allele frequency model was set to get the estimates of posterior probability of data. Ten independent runs were given setting the value of K from 1 to 5 with three iterations for each value of K. Both, length of burn-in period and number of Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) repeat after burn-in was set at 100,000. Evanno’s method (Evanno et al. 2005) based program STRUCTURE HARVESTER developed by Earl and Vonholdt (2011) was used to determine the value of estimated Ln probability of data-LnP(K) and to get the best fit value of K for the data. Highest value was shown at K = 2. Therefore, STRUCTURE analysis was conducted for K = 2. However, we also performed STRUCTURE analysis at K = 3 to compare the different clusters in relation to the groupings of dendrogram. Genetic differentiation (F st) estimates among inferred clusters were also measured by STRUCTURE software. Genetic relationships among the genotypes were also analyzed by factorial analysis using the software DARwin (Perrier and Jacquemoud-Collet 2006). Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) was performed with the help of GenAlex version 6.41 (Peakall and Smouse 2006).

Results

SSR polymorphism

Only unambiguous and reliable fragments amplified by 20 SSR primers were scored. In total, 20 primers amplified 48 fragments ranging from 1 to 4 with an average of 2.4 fragments. Size range of amplified fragments varied from 100 to 500 bp. Three primer namely, TTMS-19, TTMS-28 and TTMS-31 amplified minimum of 1 fragment while three primers namely, TTMS-1, TTMS-25 and TTMS-33 amplified maximum of 4 fragments. PIC value ranging from 0.142 for primer TTMS-8 to 0.499 for primer TTMS-7 with an average of 0.368 (Table 2). Marker index value was highest (1.95) in TTMS-25 and lowest (0.28) in TTMS-8 with a mean of 1.01 as shown in Table 2.

Cluster and diversity analysis

Dendrogram based on Jaccards similarity coefficient and UPGMA method showed three groups as shown in Fig. 2. Group-I included 11 accessions and represented majority (9) of accessions from Punjab and exceptionally included two accessions (Raj-07 and Raj-08) from Rajasthan. Group-II included 10 mixed accessions from all the three states but majority (6) of accessions was from Haryana state. The third smallest group-III contained all the five accessions from Rajasthan forming a pure group. The maximum genetic similarity value was 0.87 between Pun-09 from Rajpura and Pun-10 from Patiala showing them the most similar accessions whereas Raj-03 from Jodhpur and Pun-04 from Chhoti Baradari were found to be genetically most dissimilar with the minimum similarity value of 0.270. Dendrogram largely distinguished the different accession on the basis of their locations with few exceptions. Two dimensional graphical view of genetic diversity in 26 analyzed accessions was represented in factorial analysis (Fig. 3) which showed clearly the three groups of T. terrestris accessions. Clustering patterns in factorial supported clustering of both dendrogram and STRUCTURE. Further, AMOVA analysis revealed that the major (76 %) portion of genetic variation resided within different populations while 24 % genetic variance resided among populations.

Bayesian genetic structure

The structure harvester computed best value of K at 2. However, when we analyzed data at K = 3, the clustering largely supported the grouping of dendrogram. At K = 2, all the accessions, namely, Pun-01, Pun-02, Pun-03, Pun-04, Pun-05, Pun-06, Pun-08, Pun-09, Pun-10, Pun-11, Pun-12, belonging to Punjab clustered in cluster-I except one accession namely, Pun-07 which was collected from Punjabi University campus. On the other hand, the maximum accessions belonging to Rajasthan (Raj-01, Raj-02, Raj-03, Raj-04, Raj-05 and Raj-06) and Haryana (Har-01, Har-03, Har-04, Har-05 and Har-06) clustered in cluster-II. Mean values of F st for cluster-I and cluster-II were 0.443 and 0.440, respectively. Percentages of pure accessions in cluster-I and cluster-II were 64.2 and 58.3 %, respectively (Fig. 4). However, at K = 3, some of the accessions from the Rajasthan clustered separately and formed a pure cluster representing T. terrestris germplasm from Rajasthan.

Discussion

SSR diversity

DNA markers offer more accurate information on genetic diversity, as they are rarely influenced by environmental factors of a region (Sharma et al. 2008). Furthermore, SSR markers specifically possess many desirable useful properties which makes them most preffered DNA markers (Powell et al. 1996; Rana et al. 2015; Sharma et al. 2015). The newly developed SSR markers appeared valuable in detecting diversity in studied germplasm of T. terrestris. Twenty SSR primers generated 2.4 fragments on an average. The less numbers of alleles detected in this study may be attributed to the analyzed populations which were not so apart geographically from each other. In addition, the designed SSRs were from very less sequence data which can be from conserved and stable regions of DNA with regards to mutation rates. Eight SSR primers amplified at least three or more than three fragments and eight primers showed a PIC value greater than 0.4 which is an indicator of high polymorphism. The high genetic diversity and polymorphism observed in present study is in concordance to results of Sarwat et al. (2008). Average PIC value of 0.368 was found higher than obtained in different populations of Valeriana jatamansi and Salvadora oleoides by Jugran et al. (2015) and Yadav et al. (2014), respectively. However, this mean PIC value was comparable to the values detected in other medicinal plants by various workers (Shaw et al. 2009; Rostami-Ahmadvandi et al. 2013; Tabin et al. 2016). The average number of fragments detected per primer and, PIC and MI values showed that newly developed and characterized marker proved useful in revealing polymorphism in different populations of T. terrestris. The maximum genetic similarity value of 0.870 was observed between Pun-09 from Rajpura and Pun-10 from Patiala showing them the most similar accessions. As these two regions are not very far, high similarity is obvious. It further, indicate that even having cross-pollination and seed dispersal mechanisms, somehow this species is maintaining homozygosity in its populations which requires further investigations. The most diverse accessions were Raj-03 from Jodhpur and Pun-04 from Chhoti Baradari with the minimum similarity value of 0.270. The genetic distantness of these two accessions indicates high diversity in different germplasm prevailing in studied areas.

Cluster analysis and genetic structure

Various clustering methods give the estimate of genetic relatedness of analyzed accessions of a species. Among different clustering tools, the tools based on Baysean methods are considered more robust. Here we used both distance-based and simulation-based Baysean methods for inferring genetic relationships and structure of different T. terrestris populations. Distance-based dendrogram constructed using Jaccards similarity coefficient and UPGMA method grouped all accessions into three groups. Broadly these three groups corresponded to geographical locations of the accessions but group-I which represented majority of accessions from Punjab and group-II which represented majority of accessions from Haryana state, exceptionally included few accessions from other regions. This showed that besides, geographic isolation, different populations of this species are interrelated by some means or mechanisms which is beneficial for enhancing its genetic diversity. One small group (group-III) purely represented accessions from Rajasthan indicating conserved genetic nature of dry region germplasm. Furthermore, as this germplasm is cultivated repeated propagation of same parent germplasm may have lead to its conservative and more homozygous nature. Few exceptional groupings needs further research and analysis. Factorial analysis (Fig. 3) supported the groupings by dendrogram and showed three groups of T. terrestris accessions in which cluster representing Punjab region was having more intermixing of accessions. AMOVA analysis in present study revealed that the major portion of genetic variation resided within different populations of T. terrestris (76 %) rather than among populations (24 %). It points that allele sharing is more frequent within populations than in between populations. Baysean structure analysis indicated two genetic stocks for the entire germplasm included in present study. Cluster-I (Pun-01, Pun-02, Pun-03, Pun-04, Pun-05, Pun-06, Pun-08, Pun-09, Pun-10, Pun-11, Pun-12) belonging to Punjab showed that genetic background of accessions from Punjab was different than the accessions (Raj-01, Raj-02, Raj-03, Raj-04, Raj-05, Raj-06, Har-01, Har-03, Har-04, Har-05 and Har-06) from other two states which clustered in cluster-II. Mean values of Fst for cluster-I and cluster-II were 0.443 and 0.440, respectively, which were much higher than reported by Duran et al. (2005) in Creosotebush (Zygophyllaceae: Larrea tridentata) populations and by Fuchs and Hamrick (2010) in Guaiacum sanctum (Zygophyllaceae). This showed that genetic differentiation was high in analyzed accessions of T. terrestris than reported in the other members of family. Relative high percentages of pure accessions in both clusters indicate low admixture and natural interbreeding of accession. The reason may be distantness of the accessions included in the study. At K = 3, some of the accessions from the Rajasthan clustered separately and formed a pure cluster representing T. terrestris germplasm from Rajasthan. These observations showed that although there present only two genetic stocks for entire germplasm analyzed in this study, geographical and environmental factors have a great effect in shaping the populations of T. terrestris.

Implications for conservation and management

In the era of higher productivity and food security, many other plant species are being neglected, as the main land is used for cultivation of major crops and remaining lands are coming under various developmental processes. T. terrestris is one such plant which is frequently uprooted to replace major crops thus shrinking in minor patches. Sarwat et al. (2008) has already suggested for the conservation of diverse germplasm of this species. Furthermore, Mohammed et al. (2004) has included T. terrestris in the list of underutilized medicinal plants of Indian thar desert and suggested its commercial cultivation in this region. Although, its cultivation in dry areas can be taken as a conservation measure but duplication of same germplasm over the years can not ensure preservation of high genetic diversity in it. Further, duplicated germplasm thought to be less stable against any epidemic and therefore is not considered good in view of long-term usage and sustainable utilization. Although, high genetic diversity reported in T. terrestris here showed occurrence of valuable diverse germplasm in north India, continued negligence in some regions especially Punjab and Haryana can lead to loss of important germplasm lines. Thus, it needs attention towards conservation and introduction of diverse lines from fertile to dry regions where it is cultivated extensively to enhance genetic diversity and to ensure its conservation. To achieve this, it is suggested that introduction of various populations of T. terrestris from fertile parts of north India i.e. Punjab and Haryana should be done in north western dry parts of Rajasthan. This can result in conservation of diverse germplasm lines. Further, the demand of this herb in pharmaceutical industries will remain increasing in future, therefore, the abundantly existing resources of this species in north western dry regions needs to be utilized in a well planned way so that the industries relying on raw materials do not face any scarcity in coming years. Thus, by introducing diverse populations in north western parts will create ex situ conservatories for this species. In addition, utilization of existing resources of both fertile and dry regions in a planned manner can assure uninterrupted supply of this species to industries and its conservation for future.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this was the first attempt of SSR development in T. terrestris and these markers appeared highly polymorphic and informative in characterized germplasm. Moreover, genetic diversity and population structure related studies are severely lacking in this species. Therefore, the novel information and SSR markers provided here can be useful in accelerating these types of studies in different germplasms of T. terrestris. We found that there is considerable genetic diversity prevailing in north Indian germplasm of T. terrestris which needs preservation can be exploited in a sustainable manner. The results of present study can be helpful in planning the utilization patterns and management of T. terrestris germplasm existing in north India. The novel SSR markers developed in this study can be useful in future genetic characterization related studies of the germplasm of this species.

References

Abeywickrama K, Bean GA (1991) Toxigenic Aspergillus flavus and Aflatoxins in Sri Lankan medicinal plant material. Mycopathologia 113:187–190

Adimoelja A (2000) Phytochemicals and the breakthrough of traditional herb in the management of sexual disfunction. Int J Androl 23:82–84

Das D, Ghosh P (2014) Phytodiversity of Raiganj Wildlife Sanctuary (Kulik Bird Sancturay) of Uttar Dinajpur District in West Bengal, India. IOSR-JESTFT 8(10):79–99

Doyle JJ, Doyle JE (1990) Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus 12:13–15

Duran KL, Lowrey TK, Parmenter RR, Lewis PO (2005) Genetic diversity in Chihuahuan Desert populations of creosotebush (Zygophyllaceae: Larrea tridentata). Am J Bot 92(4):722–729

Earl DA, VonHoldt BM (2011) STRUCTURE HARVESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv Genet Resour 4:359

Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J (2005) Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol Ecol 14(8):2611–2620

Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK (2007) Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: dominant markers and null alleles. Mol Ecol Notes 7(4):574–578

Fatima L, Sultana A, Ahmed S, Sultana S (2014) Pharmacological activities of Tribulus terrestris Linn. A systemic review. World J Pharm Pharma Sci 4(2):136–150

Fuchs EJ, Hamrick JI (2010) Genetic diversity in the endangered tropical tree, Guaiacum sanctum (Zygophyllaceae). J Hered 101(3):284–291

Ganie SA (2011) Mechanism of pollination in Tribulus terrestris L. (Zygophyllaceae). Int J Pharma Bio Sci 2:B-316–B-320

Gaur R, Azam S, Jeena G, Khan AW, Choudhary S, Jain M, Yadav G, Tyagi AK, Chattopadhyay D, Bhatia S (2012) High-Throughput SNP Discovery and Genotyping for Constructing a Saturated Linkage Map of Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). DNA Res 19(5):357–373

Gauthaman K, Adaikan PG (2005) Effect of Tribulus terrestris on nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate-diaphorase activity and androgen receptors in rat brain. J Ethnopharmacol 96:127–132

Gupta RC, Kaur K, Kataria V (2016) Meiotic chromosomal studies in family Zygophyllaceae R. Br. from Rajasthan. Ind J Genet Plant Breed 76(1):111–115

Jugran AK, Bhatt ID, Suvendu Mondal S, Rawal RS, Nandi SK (2015) Genetic diversity assessment of Valeriana jatamansi Jones using microsatellites markers. Curr Sci 109(7):1273–1282

Kostova I, Dinchev D, Rentsch GH, Dimitrov V, Ivanova A (2002) Two new sulphated furostanol saponins from Tribulus terrestris. Z Naturforsch 57:33–38

Mammadov J, Aggarwal R, Buyyarapu R, Kumpatla S (2012) SNP markers and their impact on plant breeding. Int J Plant Genom 2012:728398. doi:10.1155/2012/728398

Masoudi-Nejad A, Tonomura K, Kawashima S, Moriya Y, Suzuki M, Itoh M, Kanehisa M, Endo T, Goto S (2006) EGassembler: online bioinformatics service for large-scale processing, clustering and assembling ESTs and genomic DNA fragments. Nucleic Acids Res 34:W459–W462

Mesak F, Tatarenkov A, Earley RL, Avise JC (2014) Hundreds of SNPs vs. dozens of SSRs: which data set better characterizes natural clonal lineages in a self-fertilizing fish? Front Ecol Evol 2:Article 74

Mishra R, Bisht SS (2012) Characterization of few medicinal plants from southern Orissa for their free radical scavenging property. Int J Pharm Bio Sci 3(4):(B)669–(B)675

Mohammed S, Kasera PK, Shukla JK (2004) Unexploited plants of potential medicinal value from the Indian Thar desert. Nat Product Radiance 3(2):69–74

Morrison SM, Scott JK (1996) Variation in populations of Tribulus terrestris (Zygophyllaceae). 2. Chromosome numbers. Aust J Bot 44:191–199

Pandey S (2014) Study of Preliminary Phytochemical Screening and Antibacterial Activity of Tribulus terretris against Selected Pathogenic Microorganisms. J Bioanal Biomed S 12:001. doi:10.4172/1948-593X.S12-001

Pandey S (2015) Chemoprotective Effect of Tribulus terrestris on DMBA/Croton Oil Mediated Carcinogenic Response. Acad J Cancer Res 8(1):18–27

Peakall R, Smouse PE (2006) GENALEX 6.4: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mol Ecol Notes 6:288–295

Perrier X, Jacquemoud-Collet JP (2006) DARwin software. http://darwin.cirad.fr/darwin

Petkov G (2011) Enhancement of Tribulus terrestris L. Yield by supplement of green house seedlings. Biotech Biotechnol Equip 25(2):2366–2368

Powell W, Machray GC, Provan J (1996) Polymorphism revealed by simple sequence repeats. Trends Plant Sci 1:215–222

Prevost A, Wilkinson MJ (1999) A new system of comparing PCR primers applied to ISSR fingerprinting of potato cultivars. Theor Appl Genet 98:107–112

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P (2000) Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genet 155:945–959

Rana JC, Chahota RK, Sharma V, Rana M, Verma N, Verma B, Sharma TR (2015) Genetic diversity and structure of Pyrus accessions of Indian Himalayan region based on morphological and SSR markers. Tree Genet Genomes 11:821

Roldán-Ruiz I, Dendauw J, Van Bockstaele E, Depicker A et al (2000) AFLP markers reveal high polymorphic rates in ryegrasses (Lolium spp.). Mol Breed 6:125–134

Rostami-Ahmadvandi H, Cheghamirza K, Kahrizi D, Bahraminejad S (2013) Comparison of morpho-agronomic traits versus RAPD and ISSR markers in order to evaluate genetic diversity among Cuminum cyminum L. accessions. AJCS 7(3):361–367

Rozen S, Skaletsky HJ (2000) Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. In: Krawetz S, Misener S (eds) Bioinformatics methods and protocols: methods in molecular biology. Humana Press, Totowa, pp 365–386

Sarwat M, Das S, Srivastava PS (2008) Analysis of genetic diversity through AFLP, SAMPL, ISSR and RAPD markers in Tribulus terrestris, a medicinal herb. Plant Cell Rep 27:519–528

Sharma RK, Gupta P, Sharma V, Sood A, Mohapatra T, Ahuja PS (2008) Evaluation of rice and sugarcane SSR markers for phylogenetic and genetic diversity analyses in bamboo. Genome 51:91–103

Sharma V, Bhardwaj P, Kumar R, Sharma RK, Sood A, Ahuja PS (2009) Identification and cross-species amplification of EST derived SSR markers in different bamboo species. Conserv Genet 10:721–724

Sharma V, Rana M, Katoch M, Sharma PK, Ghani M, Rana JC, Sharma TR, Chahota RK (2015) Development of SSR and ILP markers in horsegram (Macrotyloma uniflorum), their characterization, cross-transferability and relevance for mapping. Mol Breed 35:102

Shaw RK, Acharya L, Mukherjee AK (2009) Assessment of genetic diversity in a highly valuable medicinal plant Catharanthus roseus using molecular markers. Crop Breed Appl Biotech 9:52–59

Singh N, Choudhury DR, Singh AK, Kumar S, Srinivasan K, Tyagi RK, Singh NK, Singh R (2014) Comparison of SSR and SNP markers in estimation of genetic diversity and population structure of Indian rice varieties. PLoS One 8(12):e84136. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084136

Sivarajan VV, Balachandran I (1994) Ayurvedic drugs and their plant sources. Oxford and IBH Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., Oxford

Tabin S, Kamili AN, Ganie SA, Zargar O, Sharma V, Gupta RC (2016) Genetic diversity and population structure of Rheum species in Kashmir Himalaya based on ISSR markers. Flora. doi:10.1016/j.flora.2016.05.001

Tautz D (1989) Hypervariability of simple sequences as a general source of polymorphic DNA markers. Nucleic Acids Res 17:6463–6471

Temnykh S, DeClerck G, Lukashova A, Lipovich L, Cartinhour S, McCouch S (2001) Computational and experimental analysis of microsatellites in rice (Oryza sativa L.): frequency, length variation, transposon associations, and genetic marker potential. Genome Res 11:1441–1452

Topia MO, Giordano MA, Gueper HG (1994) An outbreak of Hepatogenous photosensitization in sheep grazing Tribulus terrestris in Argentina. Vet Hum Toxicol 36:311–313

Verma S, Gupta S, Bandhiwal N, Kumar T, Bharadwaj C, Bhatia S (2015)High-density linkage map construction and mapping of seed trait QTLs in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) using Genotyping-by Sequencing (GBS). Scientific Reports. doi:10.1038/srep17512

Warrier PK, Nambiar VPK, Ramankutty C, Vasudevan N (1996) Indian medicinal plants-a compendium of 500 species, 2nd edn. Orient Longman Pvt. Ltd., Chennai, pp 311–315

Yadav JP, Sandeep Kumar S, Yadav M, Kadyan S, Yadav S (2014) Assessment of genetic diversity using RAPD marker among different accessions of Salvadora oleoides of North-West India. Bioresearch Bullet 4(1):1–7

Acknowledgments

Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India is duly acknowledged for providing facilities under DBT-IPLS program at Punjabi University Patiala. First author is thankful to University Grant Commission (UGC) Govt. of India for providing her Senior Research Fellowship (SRF) under the RGNF scheme. Corresponding author is gratful to UGC for Dr. DS Kothari Post Doctoral Fellowship (DSKPDF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaur, K., Sharma, V., Singh, V. et al. Development of novel SSR markers for evaluation of genetic diversity and population structure in Tribulus terrestris L. (Zygophyllaceae). 3 Biotech 6, 156 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-016-0469-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-016-0469-8