Abstract

This paper demonstrates the first third-order autonomous linear time variant circuit realization that enhances parametric oscillation through the usage of memristor in conventional oscillators. Although the output has sustained oscillation, the linear features of the conventional oscillators become time dependent. The poles oscillate in nonlinear behavior due to the oscillation of memristor resistance. The mathematical formulas as well as SPICE simulations are introduced for the memristor-based phase shift oscillator showing a great matching.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The three basic circuit elements have recently encountered the missing fourth element—‘memristor’, relating between the flux-linkage (φ) and the charge (q), when introduced experimentally by HP labs (Strukov et al. 2008) using a thin semiconductor film (TiO2) sandwiched between two metal contacts, after the visionary hypothesis given by Chua (1971). According to Strukov et al. (2008) the memristive property naturally appears in nanoscale devices and has the potential to replace conventional transistors in memory applications (Snider 2007; Yan et al. 2010; Manem et al. 2010), as well as in cross bar switching applications (Wang et al. 2010; Young et al. 2009).

Parametric oscillator is a well known phenomenon in linear time variant system in control theory which occurs only with externally applied periodical forces as in the case of a child on a swing or quartz oscillator (Komine et al. 2003). Such oscillation does not occur automatically, rather external oscillating inputs are required to pump the system. Previously, the oscillating nature of memristor was analytically modeled under sinusoidal input (Radwan et al. 2010a, b). In our recent work (Talukdar et al. 2010, 2011), the nonlinear dynamics of memristor having oscillating resistance and dynamic poles have been presented for memristor-based Wien oscillator, which requires no external input. This letter tries to generalize those concepts in third-order system with a new insight into realizing parametric oscillation by electrical circuit requiring no input force. Mathematical analyses are carried out showing close agreement with SPICE simulations.

Memristor-based phase shift oscillator

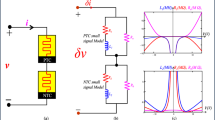

Conventional resistors are replaced (one at a time) by memristor in the phase shift oscillator (Fig. 1). RM represents the resistance of memristor. The SPICE model proposed by Biolek et al. (2009) is used to simulate the effect of memristor on phase shift oscillator. The model is implemented as a SPICE subcircuit with the following parameters: (Roff, Ron, D, μv, p) = (16 kΩ, 0.5 kΩ, 10 nm, 10−14, 10), which are the upper resistance, the lower resistance, the thin film width, the dopant mobility, and the nonlinear effect parameter. A parametric study of the initial resistance Rinit is introduced to validate the concept for different cases.

Oscillating RM

From the simulation result, sustained oscillation is found even with oscillating behavior of RM. Though Ron (0.5 kΩ) and Roff (16 kΩ) are supposed to be the most likely values for RM, RM itself shows sustained oscillation with an average value of Ravg. Figure 2 shows both the sustained output oscillation and the oscillating RM (for Rinit = 6.5 kΩ) when R1 is replaced with RM keeping R2 and R3 as 6.5 kΩ. In this figure it is clearly observed that both R2 and R3 are constant at 6.5 kΩ, whereas RM oscillates within a definite range from 6.05 to 6.95 kΩ. For this third-orderoscillatory system, RM can be expressed as:

where k is given as k = (μvRon)/D2. fM is the frequency of oscillation and VM is the voltage across RM. Rmax and Rmin are the maximum and minimum value of RM. Using (1), the amplitude swing of RM (ΔRM = Rmax−Rmin) can be estimated for any Rinit. As Rinit and Ravg are almost equal, ΔRM will essentially give the values of Rmax and Rmin as well. When R2 or R3 is replaced with RM, similar oscillation is found but with different amplitude swing. In case of R2, RM oscillates from 6.28 kΩ to 6.55 kΩ (when Rinit = 6.5 kΩ). For R3, the amplitude swing of RM is observed from 6.37 kΩ to 6.47 kΩ. Figure 3 compares the percentage error in calculating ΔRM using (1) for different Rinit. The maximum error in estimating RM from (1) is found as 1.22% (for R1 as RM), for R2 as RM the error is 6.3%, and for R3 as RM the maximum error is 5%. This oscillating RM can be the realization of periodically changing parameter. Usually in parametric oscillators, the parameters are externally applied periodically to initiate oscillation but in this memristor-based phase shift oscillator, no external means are required to have the parameter (RM) oscillating with time.

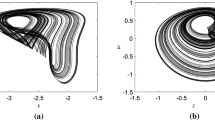

Oscillating poles

The characteristic equation of this system can be expressed as:

where m = R4/R1 (Fig. 1). There will be three roots which will be defined by the coefficients a, b, c, and d. Two of the roots are complex conjugate and the other one is real. These roots/poles determine the stability of the system, where conventionally it is believed that all the poles will be fixed in the left half of the s plane. But surprisingly in this system poles are found oscillating. From (3), it is obvious that a, b, and c are dependent on RM and as RM is sinusoidal oscillating, the poles are expected to be dynamic. In Fig. 4a (when R1 is replaced by RM), the oscillating behavior of one of the conjugate poles is plotted. Here both the real and imaginary part of complex poles are oscillating with time which means in the s plane that pole will not be fixed, rather it will oscillate from the left half s plane to the right half s plane as shown in Fig. 4b (red circle symbolizes pole). When the pole shifts to the right half plane then the oscillating RM fetches the pole from the unstable region to the stable region of the left half plane, but then RM changes its value which tends to pull back the poles towards the right half plane and this periodic incident continues. These oscillations in all three poles are observed for every Rinit as well as when R2 and R3 are also replaced by RM.

Frequency of oscillation, fM

Due to the sinusoidally oscillating RM, fM can be modeled as:

observing (4), fM will have a range of values from maximum, fM,max (when RM = Rmin) to minimum, fM,min (when RM = Rmax). fM will have a range of frequencies for oscillation but the output oscillation set itself to that frequency, when RM is equal to Ravg. Using (1) RM can be approximated to be used in (4) to calculate fM for corresponding Rinit. The maximum percentage of error in estimating fM is 0.4% when R1 is replaced by RM. In case of R2 and R3 replaced by memristor, the maximum error in calculating fM is 0.45 and 0.1%, correspondingly.

Conclusion

In spite of having oscillating resistance of memristor, and dynamic behavior of poles, sustained oscillation is observed in this memristor-based third-orderoscillatory system. For the first time, these unprecedented behaviors of memristor in oscillation can become the circuit implementation of parametric oscillation without any external means. Memristor can be considered as a better candidate than resistor for low-frequency oscillator which is widely used in programmable frequency-based counter, random number generator, synthesizing bass, random number generator, and sophisticated portable system.

References

Biolek Z, Boilek D, Biolkova V (2009) SPICE model of memristor with nonlinear dopant drift. Radioengineering 18(2):210

Chua LO (1971) Memristor—the missing circuit element. IEEE Trans Circuit Theory CT-18(5):507

Komine V, Galliou S, Makarov A (2003) A parametric quartz crystal oscillator. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control 50(12):1656–1661

Manem H, Rose GS, He X, Wang W (2010) Design considerations for variation tolerant multilevel CMOS/Nano memristor memory. In: Proceedings of the ACM Great Lakes symposium on VLSI, May 2010, Providence, pp 287–292

Radwan AG, Zidan MA, Salama KN (2010) On the mathematical modeling of memristors. In: International conference on microelectronics (ICM), pp 284–287

Radwan AG, Zidan MA, Salama KN (2010) HP memristor mathematical model for periodic signals and DC. In: IEEE International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems, Seattle, USA, pp 861–864

Snider G (2007) Architecture and methods for computing with reconfigurable resistor crossbars (Patent style), US Patent 7203789

Strukov DB, Snider GS, Stuwart DR, Williams RS (2008) The missing memristor found. Nature 453:80–83

Talukdar A, Radwan AG, Salama KN (2010) Time domain oscillating poles: stability redefined in memristor-based wien-oscillators. In: International Conference on Microelectronics (ICM), pp 288–291

Talukdar A, Radwan AG, Salama KN (2011) Generalized model for memristor-based wien family oscillators. Microelectron J 42:1032–1038

Wang FZ, Helian N, Wu S, Lim M-G, Guo Y, Parker MA (2010) Delayed switching in memristors and memristive systems. Electron Device Lett IEEE 31(7):755–757

Yan ZB, Li SZ, Wang KF, Liu J-M (2010) Unipolar resistive switching effect in YMn1-δO3 thin films. Appl Phys Lett 96(1):012103–012103-3

Young JH, Lee JY, Choi SY, Kim JW (2009) Microscopic origin of bipolar resistive switching of nanoscale titanium oxide thin films. Appl Phys Lett 95(16):162108–162108-3

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Talukdar, A., Radwan, A.G. & Salama, K.N. A memristor-based third-order oscillator: beyond oscillation. Appl Nanosci 1, 143–145 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-011-0021-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-011-0021-4