Abstract

Modern demographic and nutritional transitions have been implicated in global epidemiological transitions intensifying over the last 60 years. These transitions include steadily declining fertility rates, improving nutritional indicators, and increasing incidence rates of chronic diseases such as breast cancer. This research draws on the well established pathways linking individual reproductive and nutritional profiles to breast cancer risk, in order to test the links among demographic, nutritional, and epidemiological transitions on a global scale. We propose two hypotheses that test the reproductive and nutritional pathways that are suggested to increase breast cancer risk at the population level. We use total fertility rate (TFR) to test the reproductive behaviour hypothesis, and we use average height and the percentage of the population that is overweight for the nutritional hypothesis; these indicators are compared to breast cancer incidence rates for 2008. Accounting for national wealth and expenditures on healthcare, we found that both hypotheses were significantly associated with breast cancer incidence, although TFR appears to have a more consistent association with incidence. Drawing on our regression model, we explain trends in breast cancer incidence in selected countries, as well as making predictions about shifting breast cancer incidence rates over the next several decades. These data suggest that greater attention should be paid to the unintended health consequences of transitions that are largely considered to bring improvements in quality of life. Our findings suggest that greater investments in screening and treatment are particularly needed in regions undergoing transitions in fertility rates, particularly those areas experiencing super-low fertility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Appendix for list of countries included in this analysis.

These data include Central Asia, Europe, and North America. See Appendix for list of countries included in analysis.

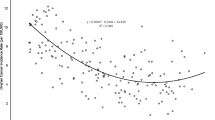

Untransformed TFR data produce a strong, significant correlation with breast cancer incidence (r = −0.754, p < 0.001). Common transformations (log, square, square root, inverse) of TFR produced similar or smaller Pearson correlations with breast cancer incidence.

References

Adami, H. O., Signorello, L. B., & Trichopoulos, D. (1998). Towards an understanding of breast cancer etiology. Cancer Biology, 8, 255–262.

Albanes, D. (1998). Height, early energy intake, and cancer. British Medical Journal, 317, 1331–1332.

Altekruse, S. F., Kosary, C. L., Krapcho, M., et al. (Eds.). (2010). SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2007. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.

American Cancer Society. (2009). Breast cancer facts and figures 2009–2010. Atlanta, GA.

Antoniou, A. C., Maher, E. R., Watson, E., Woodward, E., Lalloo, F., Easton, D. F., et al. (2006). Parity and breast cancer risk among BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Research, 8(6), R72.

Bray, F., McCarron, P., & Parker, D. M. (2004). The changing global patterns of breast cancer incidence and mortality. Breast Cancer Research, 6(6), 229–239.

Brody, J. G., Rudel, R. A., Michels, K. B., Moyisch, K. B., Bernstein, L., Attfield, K. R., & Gray, S. (2007). Environmental pollutants, diet, physical activity, body size, and breast cancer: Where do we stand in research to identify opportunities for prevention? Cancer, 109(S12), 2627–2634.

Bumpass, L. L. (1990). What’s happening to the family? Interactions between demographic and institutional change. Demography, 27(4), 483–498.

Caballero, B., & Popkin, B. M. (2002). Introduction. In B. Caballero & B. M. Popkin (Eds.), The nutrition transition: Diet and disease in the developing world (pp. 1–6). San Diego: Academic Press.

Chen, C. L., Weiss, N. S., Newcomb, P., Barlow, W., & White, E. (2002). Hormone replacement therapy in relation to breast cancer. Journal of the American Medical Association, 287, 734–741.

Chen, S., & Parmigiani, G. (2007). A comprehensive meta-analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 penetrance. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25(11), 1329–1333.

Colditz, G. A., Hankinson, S. E., Hunter, D. J., et al. (1995). The use of estrogens and progestins and the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. New England Journal of Medicine, 332(24), 1589–1593.

Colditz, G. A., & Rosner, B. (2000). Cumulative risk of breast cancer to age 70 years according to risk factor status: Data from the Nurses’ Health Study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 152(10), 950–964.

de Waard, F. (1975). Breast cancer incidence and nutritional status with particular reference to body weight and height. Cancer Research, 35, 3351–3356.

Eaton, S. B., & Eaton, S. B. III (1999). Breast cancer in evolutionary context. In W. R. Trevathan, E. O. Smith, & J. J. McKenna (Eds.), Evolutionary medicine (pp. 429–442). New York: Oxford University Press.

Eaton, S. B., Pike, M., Short, R., Lee, N., Trussell, J., Hatcher, R., Wood, J., Worthman, C., Blurton Jones, N., Konner, M., Hill, K., Bailey, R., & Hurtado, M. (1994). Women’s reproductive cancers in evolutionary context. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 69(3), 353–367.

Eaton, S. B., Strassman, B. I., Nesse, R. M., et al. (2002). Evolutionary health promotion. Preventive Medicine, 34, 109–118.

Ellison, P. T. (1999). Reproductive ecology and reproductive cancers. In C. Panter-Brick & C. M. Worthman (Eds.), Hormones, health, and behavior: A socio-ecological and lifespan perspective (pp. 184–209). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ferlay, J., Shin, H. R., Bray, F., Forman, D., Mathers, C., & Parkin, D. M. (2010). GLOBOCAN 2008, cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC CancerBase. 10 [Internet]. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr.

Greaves, M. (2007). Darwinian medicine: A case for cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer, 7(3), 213–221.

Hankinson, S. E., Colditz, G. A., & Willett, W. C. (2004). Towards an integrated model for breast cancer etiology: The lifelong interplay of genes, lifestyle, and hormones. Breast Cancer Research, 6(5), 213–218.

Hankinson, S. E., Willett, W. C., Manson, J. E., Colditz, G. A., Hunter, D. J., Spiegelman, D., et al. (1998). Plasma sex steroid hormone levels and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Journal National Cancer Institute, 90(17), 1292–1299.

Hartage, P., Stuewing, J. P., Wacholder, S., Brody, L. C., & Tucker, M. A. (1999). The prevalence of common BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among Ashkenazi Jews. American Journal of Genetics, 64(4), 963–970.

Henderson, I. C. (1993). Risk factors for breast cancer development. Cancer, 71(S6), 2127–2140.

Huang, Z., Hankinson, S. E., Colditz, G. A., et al. (1997). Dual effects of weight and weight gain on breast cancer risk. Journal of the American Medical Association, 278, 1407–1411.

Hunter, D. J., & Willet, W. C. (1996). Nutrition and breast cancer. Cancer Causes and Control, 7, 56–68.

Jasienska, G., Thune, I., & Ellison, P. T. (2000). Energetic factors, ovarian steroids and the risk of breast cancer. European Journal of Cancer Prevention, 9(4), 231–239.

Johnson-Hanks, J. (2008). Demographic transitions and modernity. Annual Review of Anthropology, 37, 301–315.

Kaaks, R. (1996). Nutrition, hormones, and breast cancer: Is insulin the missing link? Cancer Causes and Control, 7, 605–625.

Key, T. J., Appleby, P., Barnes, I., & Reeves, G. (2002). Endogenous sex hormones and breast cancer in postmenopausal women: Reanalysis of nine prospective studies. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 84(8), 606–616.

Li, C., Malone, K. E., Daling, J. R., Potter, J. D., et al. (2007). Timing of menarche and first full-term birth in relation to breast cancer. American Journal of Epidemiology, 167(2), 230–239.

Linos, E., Spanos, D., Rosner, B. A., et al. (2008). Effects of reproductive and demographic changes on breast cancer incidence in China: A modeling analysis. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 100(19), 1352–1360.

Little, M., & Haas, J. (Eds.). (1989). Human population biology: A transdisciplinary science. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Livi-Bacci, M. (2001). Too few children and too much family. Daedalus, 130(3), 139–155.

Ministry of Health, Albania. (2005). Analyses of the state of food and nutrition in Albania. Accessed online: http://www.seefsnp.org.yu/documents/albania/Analyses%20of%20State%20of%20Food%20and%20Nutrition%20in%20Albania%202005.pdf.

Moccia, P. (2008). The state of the world’s children 2009. New York: UNICEF.

Omran, A. R. (1971). The epidemiologic transition: A theory of the epidemiology of population change. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, 49(4), 509–538.

Paci, E., Warwick, J., Failini, P., & Duffy, S. W. (2004). Overdiagnosis in screening: Is the increase in breast cancer incidence rates a cause for concern? Journal of Medical Screening, 11(1), 23–27.

Parkin, D. M. (2008). The role of cancer registries in cancer control. International Journal of Clinical Oncology, 13(2), 102–111.

Popkin, B. M., & Gordon-Larsen, P. (2004). The nutrition transition: Worldwide obesity dynamics and their determinants. International Journal of Obesity, 28, S2–S9.

Porter, P. (2008). ‘Westernizing’ women’s risks? Breast cancer in lower-income countries. New England Journal of Medicine, 3583(3), 213–216.

Potischman, N., Swanson, C. A., Siiteri, P., & Hoover, R. N. (1996). Reversal of relation between body mass and endogenous estrogen concentrations with menopausal status. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 88, 756–758.

Singletary, K. W., & Gapstur, S. M. (2001). Alcohol and breast cancer: Review of epidemiologic and experimental evidence and potential mechanisms. Journal of the American Medical Association, 286(17), 2143–2151.

Smith-Warner, S. A., Spiegelman, D., Yuan, S., et al. (1998). Alcohol and breast cancer in women: A pooled analysis of cohort studies. Journal of the American Medical Association, 279(7), 535–540.

Terry, M. B., Zhang, F. F., Kabat, G., Britton, J. A., Teitelbaum, S. L., Beugut, A. I., et al. (2006). Lifetime alcohol intake and breast cancer risk. Annals of Epidemiology, 16(3), 230–240.

Toniolo, P. G., Levitz, M., Zeleniuch-Jacquotte, A., Banerjee, S., Koenig, K. L., Shore, R. E., et al. (1995). A prospective study of endogenous estrogens and breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 87(3), 190–197.

Travis, R. C., & Key, T. J. (2003). Oestrogen exposure and breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Research, 5, 239–247.

Trevathan, W. R. (2007). Evolutionary medicine. Annual Review of Anthropology, 36, 139–154.

Trevathan, W. R., Smith, E. O., & McKenna, J. J. (1999). Evolutionary medicine. New York: Oxford University Press.

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. (2005). Trends in Europe and North America: The statistical yearbook of the Economic Commission for Europe 2005. Geneva.

USAID. (2009). MEASURE DHS: Demographic and health surveys. Washington, DC.

van der Brandt, P. A., Spiegelman, D., Shiaw-Shyuan, Y., et al. (2000). Pooled analysis of prospective cohort studies on height, weight, and breast cancer risk. American Journal of Epidemiology, 152(6), 514–527.

Vitzthum, V. J., Spielvogel, H., & Thornburg, J. (2004). Interpopulational differences in progesterone levels during conception and implantation in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101(6), 1443–1448.

World Bank. (1970). World development indicators. Washington, DC.

World Bank. (2002). World development indicators. Washington, DC.

World Health Organization. (1995). Physical status: The use and interpretation of anthropometry. WHO Technical Report Series 854. Geneva.

World Health Organization. (2008). World health survey. Geneva.

World Health Organization. (2010). Global database on body mass index. Geneva.

Worthman, C. M. (1999). Evolutionary perspectives on the onset of puberty. In W. Trevathan, J. McKenna, & E. Smith (Eds.), Evolutionary medicine (pp. 135–163). New York: Oxford University Press.

Yngve, A., De Bourdeheauhuij, I., Wolf, A., et al. (2008). Differences in the prevalence of overweight and stunting in 11-year olds across Europe: The pro-children study. European Journal of Public Health, 18(2), 126–130.

Yoo, K.-Y., Tajima, K., Kuroishi, T., Hirose, K., Yoshida, M., Miura, S., et al. (1992). Independent protective effect of lactation against breast cancer: A case–control study in Japan. American Journal of Epidemiology, 135(7), 726–733.

Zahl, P., Strand, B. H., & Mæhlen, J. (2004). Incidence of breast cancer in Norway and Sweden during introduction of nationwide screening: Prospective cohort study. British Medical Journal, 328(7445), 921–924.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Countries included in selected analyses (total = 175 countries with any data available).

Age at first birth (2000–2002) and TFR (1980, 1990)

N = 46 countries.

Armenia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Israel, Italy, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Malta, Moldova, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russian Federation, Serbia and Montenegro, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, United Kingdom, United States, Uzbekistan.

% of GDP spent on health and % of women who have had mammogram

N = 73 countries.

Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Belgium, Bosnia Herzegovena, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Canada, Chad, China, Comoros, Congo, Cote d’Ivoire, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Estonia, Ethiopia, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Ghana, Greece, Guatemala, Hungary, Iceland, India, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Laos, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malawi, Malaysia, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mexico, Morocco, Myanmar, Namibia, Nepal, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Pakistan, Paraguay, Philippines, Portugal, Russia, Senegal, Slovakia, South Africa, Spain, Sri Lanka, Swaziland, Sweden, Switzerland, Tunisia, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, Uruguay, Vietnam, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

Final model: TFR, overweight, height, GDP on health, GNI, and breast cancer incidence

N = 98 countries

Argentina, Armenia, Australia, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Belgium, Benin, Bolivia, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Cameroon, Canada, Central African Republic, Chad, Chile, China, Colombia, Comoros, Congo Brazzaville, Cote d’Ivoire, Czech Republic, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Fiji, Finland, France, Gabon, Germany, Ghana, Greece, Guatemala, Guinea, Haiti, Honduras, Hungary, India, Indonesia Iran, Iraq, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Malaysia, Mali, Malta, Mauritania, Mexico, Moldova, Mongolia, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Nepal, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Niger, Nigeria, Norway, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Rwanda, Senegal, Singapore, Solomon Islands, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Swaziland, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand, Togo, Turkey, Uganda, United Kingdom, United States, Uzbekistan, Yemen, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kaiser, B., Bouskill, K. What predicts breast cancer rates? Testing hypotheses of the demographic and nutrition transitions. J Pop Research 30, 67–85 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-012-9090-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-012-9090-9