Abstract

While the association of a number of risk factors, such as family history and reproductive patterns, with breast cancer has been well established for many years, work in the past 10–15 years also has added substantially to our understanding of disease etiology. Contributions of particular note include the delineation of the role of endogenous and exogenous estrogens to breast cancer risk, and the discovery and quantification of risk associated with several gene mutations (e.g. BRCA1). Although it is difficult to integrate all epidemiologic data into a single biologic model, it is clear that several important components or pathways exist. Early life events probably determine both the number of susceptible breast cells at risk and whether mutations occur in these cells. High endogenous estrogens are well established as an important cause of breast cancer, and many known risk factors appear to operate through this pathway. Estrogens (and probably other growth factors) appear to accelerate the development of breast cancer at many points along the progression from early mutation to tumor metastasis, and appear to be influential at many points in a woman's life. These data now provide a basis for a number of strategies that can reduce risk of breast cancer, although some strategies represent complex decision-making. Together, the modification of nutritional and lifestyle risk factors and the judicious use of chemopreventive agents could have a major impact on breast cancer incidence. Further research is needed in many areas, but a few specific arenas are given particular mention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The search for specific breast cancer risk factors has been stimulated by the large differences in rates of the disease observed among countries [1], and by changes in rates in migrating populations [2, 3] and within countries over time [4, 5].

Several breast cancer risk factors have been known for many years [6, 7]. Increasing age is one of the strongest risk factors. Having a family history of breast cancer increases a woman's own risk; an earlier age at diagnosis and greater number of affected relatives augments her risk. Early age at menarche, late age at menopause, nulliparity and late age at first birth modestly, but consistently, increase risk [8]. Breastfeeding, particularly for long durations, is associated with lower risk [9]. Both height and postmenopausal body mass index are positively associated with disease, while premenopausal obesity is inversely associated, at least in Western populations [10]. A personal history of benign breast disease, particularly with atypia [11, 12], and having dense breasts on a mammogram [13] are both associated with substantial increases in breast cancer. Alcohol intake, the only dietary factor currently well established, also is associated with an increase in risk, although the relationship is modest [14].

Over the past 10–15 years substantial additional progress has been made in delineating risk factors for breast cancer. Contributions of particular note include the discovery of several gene mutations (e.g. in BRCA1, BRCA2 and PTEN genes) and quantification of the risk associated with them [15, 16]. Although long proposed [17], both observational studies and randomized trials have confirmed and quantified the important role of estrogens, both exogenous and endogenous, in breast cancer etiology. Specifically, circulating estrogen levels in postmenopausal women are positively associated with risk [18], and the use of therapies, such as tamoxifen, that block the binding of estrogen to the estrogen receptor at the breast decrease the risk of disease [19–21]. The use of postmenopausal estrogens, particularly when combined with a progestin, also increases the disease risk in women [22–25]. Furthermore, risk increases with duration of use of postmenopausal hormones. Although factors have long been suspected to influence breast carcinogenesis during early life, the hypothesis that even in utero exposures influence risk is much more recent [26] and has been increasingly supported [27, 28]. However, many methodologic challenges exist in confirming these ideas. Finally, progress has been steady in further delineating the probable protective role of physical activity [29] and in evaluating more recent dietary hypotheses such as folate intake [30].

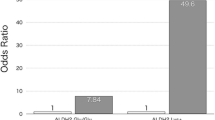

Known and suspected risk factors are presented in Table 1, and approximate strengths of association are provided for specific comparisons. Note, however, that these comparisons are somewhat arbitrary because many of these risk factors are continuous variables and the relative risks will depend on the magnitude of the contrasts chosen for comparison (e.g. a 5-year difference versus a 10-year difference in age at menopause). While many of these risk factors are established with a high degree of certainty, some, such as high prolactin levels and low physical activity, will require further research for confirmation.

A biologic model of breast cancer etiology

Mechanisms linking risk factors to the development of breast cancer are known with varying levels of certainty. Although it is difficult to integrate all epidemiologic data into a single biologic model, it is clear that several important pathways or components exist. Of critical importance in breast cancer etiology is the timing of exposure in a woman's life. For example, exposures that occur early in life can have an influence on risk that is quite different from that resulting from the same exposure occurring years later (e.g. radiation exposure [31, 32]). In addition, a single exposure can have opposing influences on risk at different times in life (e.g. parity [33]).

Early life events probably determine both the number of susceptible breast stem cells at risk and whether mutations occur in these cells. The relatively consistent positive association of risk with birthweight and the well-confirmed association with height (a marker of childhood nutritional status and associated growth factors) strongly suggest an influence of early events, perhaps even those occurring in utero, to subsequent risk. Mammographic breast density may, at least in part, be a marker of the number of at-risk cells in the breast. Mutations in these cells can be inherited (e.g. mutations in BRCA1 or p53) or acquired, such as by exposure to ionizing radiation. Oxidative damage from endogenous metabolism is hypothesized to contribute to DNA damage [34] but the importance of this mechanism to breast carcinogenesis is not clear. To the extent that oxidative damage is important, dietary antioxidants might reduce risk and their role may be particularly important early in life. Low availability of folate (and its cofactors such as vitamin B6 and B12), particularly in conjunction with high alcohol intake, can lead to abnormal DNA synthesis and repair and aberrant DNA methylation [35], and hence may play a role in breast carcinogenesis.

Pregnancy has a particularly complex influence on subsequent breast cancer risk. For about a decade after the pregnancy, risk is increased, probably due to the hormonal stimulation of already initiated breast epithelial cells [33]. In contrast, risk is reduced over the long term, possibly by rendering the breast substantially less susceptible to somatic mutations [36]. An earlier age at first pregnancy also is associated with a reduction in risk as it may shorten the time (from menarche to first birth) when the breast is particularly susceptible to mutations.

As already noted, high endogenous estrogen levels in postmenopausal women are now well established as an important cause of breast cancer, and many known risk factors appear to operate through this pathway. The additional contribution of cyclical estrogen exposure (as opposed to continuously high levels) is less clear, and much evidence indicates that progestins add to breast cancer risk [22–25]. Factors that increase lifetime exposure to estrogens and progesterone include early age at menarche, regular ovulation, and late age at menopause. Breastfeeding and being overweight during the woman's young adult life decrease the ovulatory frequency and this probably accounts, at least in part, for their protective effects. In addition to its role in folate absorption and metabolism, alcohol intake increases endogenous estrogen levels that may contribute to the observed increase in risk among regular drinkers [37, 38]. The modest increase in risk of breast cancer among current or recent users of oral contraceptives is probably due to their estrogenic (and probably progestational) effects [39]. In postmenopausal women, both adiposity and the use of postmenopausal hormones are primary determinants of estrogen exposure, and also increase breast cancer risk. Increases in physical activity can delay the onset of menarche and can also reduce the risk of breast cancer by helping to control weight gain and by modifying bioavailable hormone levels. Other growth factors in addition to estrogens, particularly insulin-like growth factor I [40] and prolactin [41], are also likely to contribute to breast cancer risk, although these relationships are less firmly established.

Importantly, estrogens (and probably other growth factors), by their mitotic effects on breast cells, appear to accelerate the development of breast cancer at many points along the progression from early mutation to tumor metastasis. By increasing cell proliferation, estrogens may also increase the probability that DNA damage is not repaired, resulting in mutations [42]. In addition, estrogens may be directly genotoxic, through their reactive metabolites [43], although evidence for this mechanism is more limited. Although exposure to high estrogen levels early in life increases risk decades later, reduction in levels late in life can reduce risk rather quickly, whether this exposure is via oophorectomy, cessation of postmenopausal hormones, or the administration of anti-estrogens. This broad outline of breast carcinogenesis, generally similar to that previously described by other scientists (see, for example [44, 45]), seems unlikely to change substantially in the future, although further research will certainly fill in details of the aforementioned relationships and will identify other contributing factors. For example, we will probably identify genetic polymorphisms that contribute to variation in endogenous levels of, or responsiveness to, estrogens and other growth factors. Also, other molecular mechanisms such as DNA repair and apoptosis are thought to be important in carcinogenesis in general, but the extent to which exogenous factors influence these processes in the context of human breast cancer is not yet known.

Current opportunities for primary prevention of breast cancer

A number of breast cancer risk factors are now well established and a subset of them, such as reproductive factors and postmenopausal obesity, account for a large part of the high breast cancer rates seen in affluent Western populations [46–48]. However, this knowledge does not necessarily translate easily into strategies for breast cancer prevention. Several risk factors (such as age at menarche or family history), while well established, are difficult or impossible to modify; some (such as alcohol intake) are well established but carry complex risks and benefits; and other risk factors (such as high vegetable and fruit consumption) are not as proven, but have other important benefits that justify the strategy, with reduction in breast cancer being a possible additional benefit. Known risk factors for breast cancer are also modest in magnitude, with relative risks generally in the range of 1.3–1.8 for attainable changes. Although these associations are not strong, they remain important. When considering primary prevention, even modest changes at the individual level can produce substantial changes in the population rates of disease [49].

Encouraging physical activity early in life is desirable and, through a modest delay in age at menarche [50, 51], should contribute to some reduction in breast cancer risk. Avoiding weight gain during adult life plays an important role in reducing the risk of postmenopausal breast cancer, as well as many other chronic diseases. Individual women can minimize weight gain by exercising regularly and moderately restraining caloric intake. It is important to note that while some strategies for breast cancer prevention, such as weight control, can be implemented by individuals themselves, the health system, governments, and society as a whole also can, and should, play a role. For example, the incorporation of increased physical activity into daily life would be greatly facilitated for both children and adults if far greater emphasis was placed on daily physical activity in schools and the provision of safe and easily accessible exercise facilities and environments (e.g. cycle paths) in the community and at the workplace.

Alcohol consumption has a complex mix of desirable and adverse health effects, one of which is an increase in breast cancer. Individuals should make decisions considering all the risks and benefits, but for a middle-aged woman who drinks alcohol on a daily basis, reducing intake is one behavioral change that is likely to reduce the risk of breast cancer. No other specific aspects of diet are well established to influence breast cancer risk. However, several dietary habits, such as high consumption of fruits and vegetables and the replacement of saturated fats and trans fats with monounsaturated fat, are important for reducing risk of heart disease [52], and could also prove to modestly decrease the risk of breast cancer.

Postmenopausal hormone use involves a complex tradeoff of benefits and risks. From the standpoint of breast cancer, the best strategy would be to use estrogens for only a few years for menopausal symptoms, if at all. In particular, the combined use of estrogen plus progestin, associated with a greater risk increase, should be avoided or minimized. The range of other pharmacologic options to treat osteoporosis has been rapidly expanding, several of which (e.g. raloxifene [20, 53]) may simultaneously reduce the risk of breast cancer. Few, if any, similarly effective options exist for alleviating menopausal symptoms, however, and research is needed to provide alternatives to currently available hormone therapy.

With the demonstration that tamoxifen, and probably other selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), can be effective in the primary prevention of breast cancer [19, 20], chemoprevention has become an option for women at elevated risk. A number of other pharmacologic agents, such as aromatase inhibitors [54], are being evaluated at present and are likely to increase the alternatives in the relatively near future. Identifying who would most benefit from these agents, all of which to date have potential adverse consequences associated with their use, remains an important issue.

In summary, available evidence provides a basis for a number of strategies that can reduce risk of breast cancer, although some of these represent complex decision-making. Together, the modification of nutritional and lifestyle risk factors and the judicious use of chemopreventive agents should have a major impact on incidence of this important disease.

Future research in breast cancer etiology

Further research is needed in many areas, but a few specific arenas deserve particular note. During most of the past several decades, epidemiologists have largely focused on adulthood exposures and risk of breast cancer. With increasing recognition that early life exposure also plays a role, a continued and expanded emphasis needs to be placed on the prenatal period through the premenopausal years. A number of innovative studies have been conducted [55, 56]; more are needed, however, as is a greater commitment to the conduct of very long-term prospective studies that start early in life. An emphasis on the validation of early exposure assessments is also needed.

The continued incorporation of advances in genetics and molecular biology into epidemiologic studies is a priority. The evaluation of gene polymorphisms and haplotypes, particularly in conjunction with environmental and other lifestyle exposures, will further our understanding of the causal nature of a number of observed associations, as well as our understanding of breast cancer etiology more generally. In addition, while most early studies considered breast cancers as a single disease entity, several studies [57, 58] have shown that risk factors vary by estrogen receptor status and progesterone receptor status of the tumor. Further molecular characterization of breast tumors will again provide substantial insight into etiology and a greater understanding of certain exposure/breast cancer relationships (e.g. an exposure that is weakly or inconsistently associated with breast cancer risk overall may be strongly associated with a particular tumor subtype). Many of these efforts, however, will require very large studies, or the pooling of data across studies.

The availability of effective chemopreventive agents, such as SERMs, has raised many questions about the optimal criteria for use of these drugs; that is, how to determine which women are at high risk and hence the best candidates for their use. Until recently, risk has been primarily based on an evaluation of family and reproductive history and a history of benign breast disease [59]. New information on risk based on genotype, mammographic density [13], and serum hormone levels [18, 53] should now allow a much more powerful prediction of risk for an individual woman – development and validation of these models is critical.

A number of other possible candidates for (chemo)prevention exist. For example, a preventive role for aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications has been suggested [60]. Further assessment of these associations with breast cancer risk, as well as intermediates such as mammographic density, may provide further avenues for prevention. The role of diet, such as folate and vitamin D intake, needs further evaluation. Other areas of emphasis should include the identification of lifestyle factors that can improve, and biologic markers that can predict, breast cancer prognosis.

Note

This article is the first in a review series titled Towards an integrated model for breast cancer etiology, edited by Hans-Olov Adami.

Other articles in the series can be found at http://breast-cancer-research.com/articles/review-series.asp?series=bcr_Towards

References

Parkin DM, Muir CS, Whelan SL, Gao YT, Ferlay J, Powell J, Eds: Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, vol. VI [International Agency for Research on Cancer Scientific Publications, No. 120]. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer Scientific. 1992

Ziegler RG, Hoover RN, Pike MC, Hildesheim A, Nomura AM, West DW, Wu-Williams AH, Kolonel LN, Horn-Ross PL, Rosenthal JF: Migration patterns and breast cancer risk in Asian-American women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993, 85: 1819-1827.

Kliewer E, Smith K: Breast cancer mortality among immigrants in Australia and Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995, 87: 1154-1161.

Ries LAG, Eisner MP, Kosary CL, Hankey BF, Miller BA, Clegg L, Mariotto A, Feuer EJ, Edwards BK, eds: SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2001. 2004, Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, [http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2001/]

Hermon C, Beral V: Breast cancer mortality rates are levelling off or beginning to decline in many western countries: analysis of time trends, age-cohort and age-period models of breast cancer mortality in 20 countries. Br J Cancer. 1996, 73: 955-960.

Kelsey JL: A review of the epidemiology of human breast cancer. Epidemiol Rev. 1979, 1: 74-109.

Willett WC, Willett WC, Rockhill B, Hankinson SE, Hunter D, Colditz GA: Epidemiology and nongenetic causes of breast cancer. In Diseases of the Breast. Edited by: Harris JR, Lippman ME, Morrow M, Osborne CK. 2004, Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 223-276. second

Kelsey JL, Gammon MD, John EM: Reproductive factors and breast cancer. Epidemiol Rev. 1993, 15: 36-47.

Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer: Breast cancer and breastfeeding: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30 countries, including 50302 women with breast cancer and 96973 women without the disease. Lancet. 2002, 360: 187-195. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09454-0.

van den Brandt PA, Spiegelman D, Yaun SS, Adami HO, Beeson L, Folsom AR, Fraser G, Goldbohm RA, Graham S, Kushi S, et al: Pooled analysis of prospective cohort studies on height, weight, and breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2000, 152: 514-527. 10.1093/aje/152.6.514.

Dupont WD, Parl FF, Hartmann WH, Brinton LA, Winfield AC, Worrell JA, Schuyler PA, Plummer WD: Breast cancer risk associated with proliferative breast disease and atypical hyperplasia. Cancer. 1993, 71: 1258-1265.

Marshall LM, Hunter DJ, Connolly JL, Schnitt SJ, Byrne C, London SJ, Colditz GA: Risk of breast cancer associated with atypical hyperplasia of lobular and ductal types. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997, 6: 297-301.

Byrne C, Schairer C, Wolfe J, Parekh N, Salane M, Brinton LA, Hoover R, Haile R: Mammographic features and breast cancer risk: effects with time, age, and menopause status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995, 87: 1622-1629.

Hamajima N, Hirose K, Tajima K, Rohan T, Calle EE, Heath CW, Coates RJ, Liff JM, Talamini R, Chantarakul N, et al: Alcohol, tobacco and breast cancer – collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 53 epidemiological studies, including 58,515 women with breast cancer and 95,067 women without the disease. Br J Cancer. 2002, 87: 1234-1245. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600596.

Ellisen LW, Haber DA: Hereditary breast cancer. Annu Rev Med. 1998, 49: 425-436. 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.425.

Greene MH: Genetics of breast cancer. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997, 72: 54-65.

Henderson BE, Ross RK, Pike MC, Casagrande JT: Endogenous hormones as a major factor in human cancer. Cancer Res. 1982, 42: 3232-3239.

Endogenous Hormones and Breast Cancer Collaborative Group : Endogenous sex hormones and breast cancer in postmenopausal women: reanalysis of nine prospective studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002, 94: 606-616.

Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Redmond CK, Kavanah M, Cronin WM, Vogel V, Robidoux A, Dimitrov N, Atkins J, et al: Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer – report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998, 90: 1371-1388. 10.1093/jnci/90.18.1371.

Cummings SR, Eckert S, Krueger KA, Grady D, Powles TJ, Cauley JA, Norton L, Nickelsen T, Bjarnason NH, Morrow M, et al: The effect of raloxifene on risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. JAMA. 1999, 281: 2189-2197. 10.1001/jama.281.23.2189.

Cuzick J, Forbes J, Edwards R, Baum M, Cawthorn S, Coates A, Hamed A, Howell A, Powles T, IBIS investigators: First results from the International Breast Cancer Intervention Study (IBIS-I): a randomised prevention trial. Lancet. 2002, 360: 817-824. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09962-2.

Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer: Breast cancer and hormone replacement therapy: collaborative reanalysis of data from 51 epidemiologic studies of 52,705 women with breast cancer and 108,411 women without breast cancer. Lancet. 1997, 350: 1047-1059. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08233-0.

Writing Group for the Women's Health Initiative Investigators: Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002, 288: 321-333. 10.1001/jama.288.3.321.

Colditz G, Rosner B: Cumulative risk of breast cancer to age 70 years according to risk factor status: data from the Nurses' Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2000, 152: 950-964. 10.1093/aje/152.10.950.

Schairer C, Lubin J, Troisi R, Sturgeon S, Brinton L, Hoover R: Menopausal estrogen and estrogen–progestin replacement therapy and breast cancer risk. JAMA. 2000, 283: 485-491. 10.1001/jama.283.4.485.

Trichopoulos D: Hypothesis: does breast cancer originate in utero?. Lancet. 1990, 335: 939-940. 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91000-Z.

Okasha M, McCarron P, Gunnell D, Smith GD: Exposures in childhood, adolescence and early adulthood and breast cancer risk: a systematic review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003, 78: 223-276. 10.1023/A:1022988918755.

Potischman N, Troisi R: In-utero and early life exposures in relation to risk of breast cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 1999, 10: 561-573. 10.1023/A:1008955110868.

Gammon MD, John EM, Britton JA: Recreational and occupational physical activities and risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998, 90: 100-117. 10.1093/jnci/90.2.100.

Zhang S, Hunter DJ, Hankinson SE, Giovannucci EL, Rosner BA, Colditz GA, Speizer FE, Willett WC: A prospective study of folate intake and the risk of breast cancer. JAMA. 1999, 281: 1632-1637. 10.1001/jama.281.17.1632.

Miller AB, Howe GR, Sherman GJ, Lindsay JP, Yaffe MJ, Dinner PJ, Risch HA, Preston DL: Mortality from breast cancer after irradiation during fluoroscopic examinations in patients being treated for tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 1989, 321: 1285-1289.

Land CE, Tokunaga M, Koyama K, Soda M, Preston DL, Nishimori I, Tokuoka S: Incidence of female breast cancer among atomic bomb survivors 1950–1985. Radiat Res. 1994, 138: 209-223.

Lambe M, Hsieh C, Trichopoulos D, Ekbom A, Pavia M, Adami HO: Transient increase in risk of breast cancer after giving birth. N Engl J Med. 1994, 331: 5-9. 10.1056/NEJM199407073310102.

Ames BN, Gold LS, Willett WC: The causes and prevention of cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995, 92: 5258-5265.

Mason JB, Levesque T: Folate: effects on carcinogenesis and the potential for cancer chemoprevention. Oncology (Huntingt). 1996, 10: 1727-1743. [discussion, 1743–1744]

Russo J, Russo IH: Toward a unified concept of mammary carcinogenesis. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1997, 396: 1-16.

Dorgan JF, Baer DJ, Albert PS, Judd JT, Brown ED, Corle DK, Campbell WS, Hartman TJ, Tejpar AA, Clevidence BA, et al: Serum hormones and the alcohol-breast cancer association in postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001, 93: 710-715. 10.1093/jnci/93.9.710.

Reichman ME, Judd JT, Longcope C, Schatzkin A, Clevidence BA, Nair PP, Campbell WS, Taylor PR: Effects of alcohol consumption on plasma and urinary hormone concentrations in premenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993, 85: 722-727.

Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer: Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 53 297 women with breast cancer and 100 239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 1996, 347: 1713-1727. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90806-5.

Renehan AG, Zwahlen M, Minder C, O'Dwyer ST, Shalet SM, Egger M: Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I, IGF binding protein-3, and cancer risk: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Lancet. 2004, 363: 1346-1353. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16044-3.

Clevenger CV, Furth PA, Hankinson SE, Schuler LA: The role of prolactin in mammary carcinoma. Endocr Rev. 2003, 24: 1-27. 10.1210/er.2001-0036.

Preston-Martin S, Pike MC, Ross RK, Jones PA, Henderson BE: Increased cell division as a cause of human cancer. Cancer Res. 1990, 50: 7415-7421.

Liehr JG: Is estradiol a genotoxic mutagenic carcinogen?. Endocr Rev. 2000, 21: 40-54. 10.1210/er.21.1.40.

Adami HO, Persson I, Ekbom A, Wolk A, Pontén J, Trichopoulos D: The aetiology and pathogenesis of human breast cancer. Mutat Res. 1995, 333: 29-35. 10.1016/0027-5107(95)00128-X.

de Waard F, Trichopoulos D: A unifying concept of the aetiology of breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 1988, 41: 666-669.

Madigan MP, Ziegler RG, Benichou J, Byrne C, Hoover RN: Proportion of breast cancer cases in the United States explained by well-established risk factors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995, 87: 1681-1685. 10.1093/jnci/87.22.1681.

Colditz GA: A biomathematical model of breast cancer incidence: the contribution of reproductive factors to variation in breast cancer incidence. In Accomplishments in Cancer Research 1996. Edited by: Fortner JG, Sharp PA. 1996, Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven, 116-121.

Huang Z, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Hunter DJ, Manson JE, Hennekens CH, Rosner B, Speizer FE, Willett WC: Dual effects of weight and weight gain on breast cancer risk. J Am Med Assoc. 1997, 278: 1407-1411. 10.1001/jama.278.17.1407.

Rose G: Strategy of prevention: lessons from cardiovascular disease. Br Med J Clin Res. 1981, 282: 1847-1851.

Merzenich H, Boeing H, Wahrendorf J: Dietary fat and sports activity as determinants for age at menarche. Am J Epidemiol. 1993, 138: 217-224.

Mosian J, Meyer F, Gingras S: Leisure, physical activity and age at menarche. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1991, 23: 1170-1175.

Hu FB, Willett WC: Optimal diets for prevention of coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2002, 288: 2569-2578. 10.1001/jama.288.20.2569.

Cummings SR, Duong T, Kenyon E, Cauley JA, Whitehead M, Krueger KA, Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) Trial: Serum estradiol level and risk of breast cancer during treatment with raloxifene. JAMA. 2002, 287: 216-220. 10.1001/jama.287.2.216.

Goss PE, Strasser-Weippl K: Aromatase inhibitors for chemoprevention. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004, 18: 113-130. 10.1016/S1521-690X(03)00070-8.

Michels KB, Ekbom A: Caloric restriction and incidence of breast cancer. JAMA. 2004, 291: 1226-1230. 10.1001/jama.291.10.1226.

Vatten LJ, Romundstad PR, Trichopoulos D, Skjaerven R: Pre-eclampsia in pregnancy and subsequent risk for breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2002, 87: 971-973. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600581.

Colditz GA, Rosner BA, Chen WY, Holmes MD, Hankinson SE: Risk factors for breast cancer according to estrogen and progesterone receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004, 96: 218-228. 10.1093/jnci/djh025.

Potter JD, Cerhan JR, Sellers TA, McGovern PG, Drinkard C, Kushi LR, Folsom AR: Progesterone and estrogen receptors and mammary neoplasia in the Iowa Women's Health Study: how many kinds of breast cancer are there?. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1995, 4: 319-326.

Gail MH, Brinton LA, Byar DP, Corle DK, Green SB, Schairer C, Mulvihill JJ: Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast cancer for white females who are being examined annually. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989, 81: 1879-1886. 10.1093/jnci/81.24.1879.

Baron JA: Epidemiology of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cancer. Prog Exp Tumor Res. 2003, 37: 1-24.

Acknowledgements

Adapted in part from an earlier review 'Epidemiology and nongenetic causes of breast cancer' [7]. The authors apologize to colleagues whose work could not be cited because of space limitations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hankinson, S.E., Colditz, G.A. & Willett, W.C. Towards an integrated model for breast cancer etiology: The lifelong interplay of genes, lifestyle, and hormones. Breast Cancer Res 6, 213 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr921

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr921